Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bruno Gmünder Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

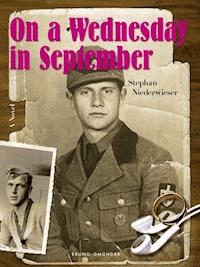

When Edvard hands his lover a ring to seal their friendship, he triggers an emotional avalanche: Bernhard is overwhelmed with images from the past: Nazi Germany, a blond soldier, and trails of blood in the snow. While seeking answers to these haunting images Bernhard crosses paths with many strangers: his close-lipped father, stewardess Kim, grand seignior Raimondo, gigolo Fred, and his own strong-willed mother Lydia. The ring connects the lives of these strangers, and what seems contradictory finally comes together. On a Wednesday in September, one of Germany's best-selling gay novels, is finally available in English.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my father

Inhalt

Prologue

Kapitel 1.

Kapitel 2.

Kapitel 3.

Kapitel 4.

Kapitel 5.

Kapitel 6.

Kapitel 7.

Kapitel 8.

Kapitel 9.

Kapitel 10.

Kapitel 11.

Kapitel 12.

Kapitel 13.

Kapitel 14.

Kapitel 15.

Kapitel 16.

Kapitel 17.

Kapitel 18.

Kapitel 19.

Kapitel 20.

Kapitel 21.

Kapitel 22.

Kapitel 23.

Kapitel 24.

Kapitel 25.

Kapitel 26.

Kapitel 27.

Kapitel 28.

Kapitel 29.

Kapitel 30.

Kapitel 31.

Kapitel 32.

Kapitel 33.

Kapitel 34.

Kapitel 35.

Kapitel 36.

Kapitel 37.

Kapitel 38.

Kapitel 39.

Kapitel 40.

Kapitel 41.

Kapitel 42.

Kapitel 43.

Kapitel 44.

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Imprint

PROLOGUE

He marches through a gate stretched menacingly against the sky like a fist defying the enemy. Flags blaze like eternal flames; swastikas whirl gloomily in the wind. Comrades look up, wrenching their hands into Hitler salutes—blinded by his shining insignia, they squint. Above his head, squadrons of fighter jets zip past. Playfully, they form triangles and enormous circles, effortlessly melting into figures of eight, virtuous and proud as the men who fly them.

Though he’s marching on gravel, he can’t hear his own steps. Even later, cowering in the field, hiding his face in the dew-soaked grass, he cannot feel the tickling blades. He watches the enemy as they advance over the hill like a dark green wave. His finger decides over life and death. A single rehearsed motion and he will save them all: his comrades, his family, his fatherland. He needs only to focus, breathe calmly and wait for the right moment. Wait, breathe and focus.

“Philipp! Philipp!” His pulse raced; his muscles tensed. Terrified, his eyes widened as he caught sight of the pale, gleaming face. He wanted to jump up, stand at attention, and reach for his weapon, as they had trained him to do at the academy. There, in the glow of the flickering lamp, was his mother.

“Your father told me not to worry,” she whispered agitatedly, lowering her head. She had always been tall and large, but that night she had withered away to a shadow of herself.

“You needn’t be afraid,” Philipp said woodenly, grasping the bedspread. It was warm and heavy; he felt safe beneath it.

They had made it clear to him that he needed to be strong. They had explained why it was necessary to defend Germany from evil forces, to regain the honor his fatherland had lost during the Great War. And they had made it clear that everyone who was afraid was a coward, a worthless good-for-nothing.

“I’ll take care of myself,” he said, his stomach heaving. His hands and feet felt icier than the dream-soaked breath freezing on the window into finely veined crystals.

Snowflakes drifted down gently outside, covering the footprints of all the sons who had left in these last days. Philipp’s mother set the lamp down on the night table. A piece of the wick flared up and went out. In a few hours, the rising sun would warm the cool walls of this room. Its light would break into crystals, casting playful dabs of color onto the worn floorboards. It would melt a few icicles that were clinging to the gutter, causing them to fall and split the snow, pushing into the earth like a draft notice into the heart of a mother. No, the greatest pain in a woman’s life was not to give birth to a child. It was much more painful to let the child go, to see him taken by a war from which hardly anyone returned.

“This is for you!” she said, pressing a piece of flesh-warmed metal into his hand. She looked into the blue pools of his eyes, through which she had once been able to see straight into his mind. But tonight they were as veiled and gray as all the lies of this time.

Philipp studied the ring as it caught and reflected the light, penetrating the oppressive darkness of the room. Wide-eyed, he let the blanket fall, uncovering his pale torso, the deep cavity in the middle of his chest.

“It is the Ring of Lovers,” his mother said, staring at Philipp as if trying to engrave his image into her memory. “I wanted to keep it until you had found the right girl. But I’m giving it to you now because…” She hesitated. Hardship and loneliness would fill the place where Philipp had once built castles out of pieces of rock, where he had once carved reeds into shrill whistling flutes. Soon his bed would be as empty as her heart. “…because it will protect you.”

His eyebrows were as delicate as lines drawn in charcoal; his long lashes reflected the light, capturing it in an aureole around his eyelids.

With a warm finger, she drew three crosses on his flat brow. A tear ran down her cheek, and Philipp understood that his mother would not be standing in the door the next morning to see him off.

The floor creaked beneath her feet, the door shut with a dull thud. Philipp couldn’t take his eyes off the ring, its gold bands wound like ribbons or hands clasped together. Two stones were embedded in it: a ruby and a diamond. The gold was polished, as if no one had worn it before.

He turned down the flame and put his mother’s gift on his finger. It carried him away into his dreams as softly as a stone sinking into a pond: bombs falling noiselessly, tanks reducing enormous trees to sawdust beneath them, machine guns rattling in slow motion, as slow as a heart’s beat. Lead raining down hotly while smiling soldiers melt into the steaming ground and Philipp crosses an open field towards a far light. An altar—and behind it, in the pews of a chapel, people whispering happily. At the end of the aisle, a bride.

“I’m getting married! I’m getting married!” his heart rejoices.

“…by the power vested in me, I now pronounce you man and wife.”

Air raid sirens drone harmoniously above the ceremony, only drowned out by the priest’s voice: “You may now kiss the bride” the words echo like church bells in his head and fade away. Philipp lifts the veil and kisses the firm, strong lips of a handsome soldier.

1.

By swaying a few inches to the right or left, he could make the trees seem to move: imperfections in the glass window transformed sturdy branches into breathing diaphragms. Behind him a murmur welled up.

Bernhard Moll turned to face his students. He often paused in this manner, having learned that imparting facts alone was not enough to inspire understanding. Repose was necessary, the depth of silence; this alone allowed knowledge to grow. A lesson is like an infusion of black tea, leaf fragments swirling excitedly about. It must be allowed to sit a while until the leaves coalesce, in the bottom of the pot, into images and ideas.

There were girls who had tears in their eyes when they saw their teacher standing like this. For them, these were not moments to process what they had heard, but their only opportunity to catch a glimpse behind the outer façade of this man, who often seemed far too mature.

“Good, then let’s summarize. Which factors contributed to the breakdown of the Weimar Republic?” He looked around at their pale faces.

“Yes?” He pointed to a young man in the last row.

“The fear of a revolution.”

“Right. What else?”

“Inflation.”

“Good. Germany was suffering under enormous inflation: one dollar to four billion Marks. What else?” Bernhard Moll slowly went up to the board.

“Extreme unemployment rates. In 1930 it was more than 20 percent, with 30.000 bankruptcy proceedings on top of that.”

“Exactly, and what else—very important!” He raised his index finger above his head, a caricature of himself: tall and thin, with a slight kink in his neck, like a bendable straw. Sometimes it seemed as if he would just break down, but he never did, at least not in school.

“Racist paramilitary groups and the influence of the growing national socialist party, whose member lists grew proportionally with the rise in unemployment.”

It made the faculty uncomfortable that students learned more in Bernhard Moll’s class than from any of his colleagues. It couldn’t be because of his appearance, the conspirators all agreed on that. What was attractive about a man in his mid-thirties who still dressed, in the 90s, the way he had in his youth? His face looked creased and tired; dark curls raged on his slim head. There was no elegance to his awkward movements, his long limbs that flapped around as if they didn’t belong together, his bony, much too white hands that knocked against the desks as he walked around the room or made the chalk screech across the blackboard.

His colleagues viewed these pauses as a waste of time, a breeding ground for inattentiveness, the seeds of disobedience. They didn’t understand that in those moments, time stood still—time, and the world itself. They couldn’t see with the eyes of fifteen-year-old girls.

Yet they had never found an opening to take a shot at him. Bernhard Moll was much too friendly and courteous, far too obliging. Besides, he seemed to carry a shield of compassion around with him, a constant pain in his eyes, a pain he himself could not name. This something pulled at the corners of his mouth, made his eyebrows slope off suddenly at the sides, and impressed a helpless dimple no bigger than the tip of a tongue above his nose. His appearance made people want to protect him, not attack him.

It was simply impossible not to like him, even if—or perhaps because—one didn’t try to get to know him. And, for his students, there was another reason: there was something fundamentally good about him. “It’s a shame that he’s a teacher,” a girl once said in the schoolyard, and the others had sighed in agreement.

“Is that all clear?” He turned around, looking for questions in his students’ eyes. Nothing.

The sound of a scribbling pencil reached his ears. It sounded excited, purposeful, defiant. Bernhard turned to the source of the noise. “Are you filling our reflective pauses with art?”

The student shrugged as Bernhard suddenly grabbed the sheet from him, a sketch of a handsome young man with wild hair, much-too-narrow pants, and a seductive expression. Bernhard folded it and hid it behind his back without commentary.

“Or are you not interested in what we are doing?”

The student looked at him wide-eyed and turned red. “I mean, this is total garbage, isn’t it?”

“Garbage?” Bernhard went to the board. “An important comment! Much obliged. So—is there any point in still thinking about all this after sixty years have gone by?” He let the caricature fall onto his own desk, watching it glide over his papers.

“No,” piped up a dry voice from the third row. The students laughed. The boy beamed at him defiantly.

“Stand up!” he said. “Come on, stand up!”

The student followed his command hesitantly.

“Close your eyes!”

The boy didn’t understand. Bernhard went up to him and placed his hand over his eyes.

“Take a few steps, and tell me what you notice.”

The student took two steps. “Nothing. What am I supposed to notice?”

“What do you feel under your feet? What do you hear?”

“Linoleum.”

“Okay. Now come up to the blackboard.”

Bernhard looked for something on the evenly green surface. “Here, right here.” He pointed to a particular spot. “What do you see here?”

“A blackboard.” He turned proudly around to his fellow students, who laughed.

“Clever, really clever.” Bernhard drew a circle with chalk. “What do you see inside this circle?”

“Green.”

“Good, very good.”

He soaked the sponge with water and pressed it against the board for a moment, then took it away again.

“What do you see now?”

“A wet blackboard.”

Bernhard grabbed him by the neck and pushed his face up closer to the blackboard.

“And now?”

The student hesitated for a moment, the color draining from his face. He saw that Bernhard was serious.

“I see…I see…the wood bulging out underneath the surface.”

“Thank you.” Bernhard pushed him back to his seat. Then he wandered, deep in thought, between desks defaced with inky scribbles and chairs stuck with chewing gum. His thoughtful steps echoed under the high ceiling.

“Linoleum doesn’t yield. It doesn’t creak either, unless…?”

“There’s a layer of wood underneath it.”

“Bingo! What we see is an unwashed linoleum floor, but something very different is hidden beneath it. It’s the same with the blackboard. We see a consistently green surface. A little bit of water, and the wood beneath it becomes visible. Understand?”

A few heads nodded back at him, but there were still question marks on most of the faces.

“What I want to say is that the past is often much closer to us than we perceive it to be.”

He went slowly around the room. Another one of those timeless pauses arose. The entire classroom seemed to sink into stillness; the floor creaked beneath his feet.

“Consider our economic situation. Some circumstances that we’re coping with today were also present before the war: growing unemployment, cutbacks to the welfare state, racism, conservative influences, very, very conservative influences even. Does that mean we’re heading towards a Fourth Reich?” He stood still and looked out over the entire class.

“Just say what you think. What is your opinion on this?”

The students looked down at their books, embarrassed; a few girls turned to face him expectantly. It was an unreasonable question; that became clear to him as his eyes ranged through the classroom, lingering on the posters advertising jeans, on the close-up photos of stars with seductively distant expressions. What did a fifteen-year old care if the Third Reich returned, if his favorite actor was lovesick, or is his favorite soccer player had just missed a penalty shot?

“No,” one of the boys said, just to break the silence.

A glimmer of hope flashed over Bernhard’s face. “Now explain to me why not.”

“No idea. Maybe because people don’t even trust our chancellor. Who could become as powerful as Hitler?”

“Okay. Who has another idea?”

“I mean, maybe it hasn’t gotten bad enough yet. In a few years, if things just keep getting worse, and the issue of political asylum seekers becomes correspondingly more heated…”

“Yeah, and then all it would take is for a minority to be seemingly better off than the majority…” the girl sitting next to him finished.

“…and there would be quite a lot of fuel. Well reasoned.” Bernhard took a long pause.

“Is that really going to happen?” one of the students asked, his eyes opened wide in fear.

“Is it?” Bernhard took a few steps. “I wasn’t trying to predict the future with that question, I’m not a prophet. But I wanted to show you that it’s necessary to understand the past in order to get an idea of where we are heading. Only when we know where we’re coming from can we know where we’re going.”

“And what about the war in Yugoslavia?” someone answered defiantly. “We knew that thousands of Muslims were executed. That was no different from how it was with Jews back then. But nevertheless nobody cared about it.”

“Your objection only seems to be correct,” Bernhard answered, “but when it comes to understanding the past, the question is always who is using the information and how. For example, if you explain how robberies are committed, people can protect themselves better. At the same time you’re giving potential crooks tried and tested instructions. Does that mean that it’s better to keep quiet about the truth?” Bernhard looked questioningly at his students. Some of them murmured, some of them shrugged their shoulders, and some had already closed their books.

“Do you understand what I’m trying to say?” He looked at the clock: thirteen minutes to one. This discussion was not going to be wrapped up in three minutes.

“I just wanted to say one thing: if you don’t concern yourself with the past, you are robbing yourself of the chance to understand the present.” He looked around. Frowns.

“When we have the chance, we should follow up on this,” he said. “Those are my closing words before vacation. I hope you’ll get lots of presents, a good chance to relax, and that no one comes back from a ski trip with broken bones!”

The students jumped up, a few crumpled balls of paper flew through the room, a girl fell into her boyfriend’s arms, then the room emptied quickly.

Two girls approached Bernhard hesitantly. One of them held a lavishly wrapped package in her hands. Bernhard looked up, saw the girl, saw the gift, and turned his head back to his desk.

“For you,” she said, turning red, and held out the present to him.

“That is very nice—and entirely unnecessary.” Bernhard smiled, but he was uncomfortable. The two girls stood stock still in front of him. “Have a nice vacation,” he said and turned to his desk again. But their yearning eyes stayed fixed on him. He looked at them again and nodded. “Don’t forget the assignments for January. Now be on your way.”

They sauntered off; Bernhard watched them go. As soon as he was alone, he sat down on his desk and picked up the drawing. An echo of his past overtook him, filling him with memories that he had long since repressed. Pain caused a shiver to run through his skin. He hoped this young man would be spared all that.

Bernhard raised his eyebrows high, deepening the dimple above his nose. Then he stuffed his papers in a battered leather satchel, stuck the present under his arm and plunged into the chaos of students in the corridor.

“You ready for the Christmas party in the faculty lounge tonight?” The question caught him on his way into the main building. It sounded familiar, friendly and inviting, but Bernhard grew stiff. He turned around and looked into the perky eyes of a small, dainty woman. Her fire-red hair lay curled up like a sleeping cat on her too-small head. She was carrying a pile of books in her arms. To balance herself, she was leaning back from the hips.

“Ruth!” He looked around and whispered. “I…um…I won’t be able to make it.”

They had known each other since they were students. There was a time when people had referred to them as inseparable, and their friends back then had assumed they would end up getting married. But that was long ago.

“Now why do I have the feeling you don’t want to tell me why you’re not coming?”

She lowered her long lashes against the harsh sunlight.

Bernhard looked down at the ground.

“Whatever it is,” she said, “At some point I’ll discover your secret.”

He lifted his head; his injured smile awoke her protective instincts. She leaned over and held out her cheek.

“Maybe you’ll have time for a cup of tea over vacation.”

“Of course,” he said much too quickly. “I’m going to see my family in Frankfurt tomorrow, but I’ll be back by Monday at the latest.”

“Call me!”

Bernhard gave her a brief kiss. Then Ruth moved away. Her pointed boots clacked off down the hallway, then she disappeared in the shadows of the classroom doors.

An aroma of citrus reached his nostrils. A young man sitting across from Bernhard in the tram was peeling an orange. His eyes were large and alert, his face smooth and shockingly pale. He was perhaps twenty or twenty-two, in any case much too erotic for his age. An aura of warm physicality surrounded him, an aura of bodies wrestling in twisted sheets. His lips were dangerously moist. And when he lifted his lips from the sweet fruit and saw Bernhard, he opened his mouth—only a small gap wide, but Bernhard was afraid it would swallow him up. He grasped his briefcase, but he needed more support, so he stood up and grabbed one of the poles. He started to sweat. A baby in a stroller saw his face and frowned. Bernhard started laughing; the child chuckled and clapped its hands. Then it contorted its face, as if it were trying to imitate Bernhard’s expression. Now it was Bernhard’s turn to chuckle.

“Next stop, Karlsplatz Stachus.” He went down the steps into the cold, then turned around and helped the young woman struggling with her stroller. A quick pull, a smile, a nod. The older woman, who must have been her mother, said: “Now isn’t that man friendly? Look how helpful he is.” And then, to him: “Thank you, sir. Nowadays, one seldom encounters men like you.” Bernhard lowered his head and moved away quickly.

Pulling his bordeaux-red knitted cap with its earflaps and pompom down over his face, he walked along the crowded pedestrian mall towards Marienplatz. The air was heavy with cinnamon and cloves; it promised so much, and contained so little.

Reaching the Christkindl market, Bernhard roamed among stalls selling porcelain replicas of half-timbered houses: made in China, of course. There were thick Bavarian stockings from Taiwan, mulled wine without the wine, and small hand-made reverse glass paintings, winter scenes of Filipino craftsmanship.

Bernhard looked up at the hundreds of branches covered with lamps spread around the broad trunk of the Christmas tree like a skirt. He saw that the figurines and the tips of the city hall’s towers were covered with snow like a gingerbread house caked with icing and for the first time this year, Bernhard felt like it was actually Christmas. He could sense it, he could smell it, he could taste it. Comfortable evenings by the fire, good food, heavy aromas and a stillness that contained far more than the mere absence of noise. For a short moment his work slipped away from him, peace spread through his head like an impenetrable blanket of snow, a white vastness settled in place of the raging din of students. Freedom.

He stood still, his boots sunk deep in the snow. He looked up on the statue of the Virgin Mary, which glimmered strangely. People jostled against him constantly in passing, but he felt the tension of the past few days fall away nevertheless. He breathed in peace.

Then he heard a scream. A man lay on the ground, twitching, while a woman kneeled next to him, crying, and everything was suddenly changed. The sweet air became heavy and thick, much too thick to fill the tiny sacs of a lung. The vastness of Bernhard’s thoughts shrank into a space scarcely wider than a needle’s eye. Panic mingled with the Christmas carols, immobile observers breathed deep as if their own hearts were threatening to stop.

“Everything can change so quickly,” he heard a voice say. He turned around. An old woman with a bent back, carrying heavy plastic bags, chewed the words from her toothless mouth. “No one knows what the Lord has in mind for us.”

Bernhard didn’t notice how cold it had become until he arrived home. His apartment was damp; thick drops of condensation on the windows muddied the waning daylight. He laid his hand on the radiator: cold. He must have forgotten to turn it on. The thermostat said 56 degrees. He put down the present, placed his briefcase on the chair, since there was no more room on his desk, fished out his student’s drawing and pinned it to the corkboard already overflowing with pieces of paper. Then he swept the small snowflakes, which had melted to drops of water, from his coat and hung it on the door to the living room.

He set the teakettle on the gas stove and turned it on. In the cupboard, he found a cup of instant soup; on the back of an envelope from the IRS he put together a small list of things not to forget when he went to visit his family: toothbrush, underwear, sleeping bag. Where was it, actually? Bernhard looked in the storeroom, in his dresser, behind his books. By his coat rack he found his suitcase, but not the sleeping bag. He looked in the dresser.

No sleeping bag, but the teakettle was whistling. He poured out his soup and scribbled more things on his list: aspirin, gifts, book: The Thirty Years’ War.

He sipped his soup. Bernhard had always intended to write up a packing list on his computer. Then he remembered. He turned on the computer and entered the keyword “sleeping bag” in the search field. The database window opened, and there it was: On the shelf above the door. He retrieved it and laid it down next to his travelling bag, then turned back to his lunch. By the time he sat down at his desk around three o’clock, the thermostat had risen to 76, and the windowpanes were still covered, though now with fat drops of water.

Books about World War II were piled against the walls: teaching materials for the months to come. He had been meaning to prepare for weeks, but kept putting it off. He turned the books with their backs facing the wall, so their titles wouldn’t be staring at him any longer, pushed some materials to the side and took down the math assignments for 11A from the shelf. He switched on the lamp on the writing desk and looked over the first exercises.

Bernhard loved math. He loved numbers, their indisputable clarity. They weren’t susceptible to influence; rather, they were subject to exact laws, and above all they were predictable. They could be added and subtracted, multiplied, or their wonderful roots could be extracted, and everywhere, whether in the thin air over the summits of the Himalayas or in the humid, steaming heat of the jungle, whether on a bullet train or two miles below sea level, the result would always be the same. One and one were two, that was the way it was. At least most of the time.

History was similar, or at least that was what he had assumed when he began studying. It was in the past, it couldn’t be altered anymore, so it must be predictable. However, as he had learned over the years, a diary or a new statement from a witness could change everything, and history books had to be rewritten—or at least, they should be. This threw the whole idea of predictability out the window. If, as had often happened, a single typo could turn history upside down, how did history react to conscious manipulation, to the suppression of information? Entire generations lived believing in false realities. They assumed events to be factual that had never happened the way they thought. And based on these false representations, they made decisions for the future. If they were ever to find out the truth, worlds would collide.

Weariness overcame him, and Bernhard stood up and went to lie down on the couch of his 180-square feet study-living-dining-guest-room. He wanted to calm down for a while before he plunged into the evening’s adventures.

He reached for the catalog for the Rubens retrospective. He had used to study history books in every moment of his free time. But when it became clear to him that what was written in them was only one view of reality, he wanted to read everything and learn everything: the more one knew, the more one understood—or so he believed back then. As time went by, he had learned that it was sometimes better to just forget the past.

2.

The sky was clear and cloudless, full of stars, as if someone had attempted to paint over wax wallpaper with black paint. Slowly, Bernhard’s eyes became accustomed to the dark. A shooting star burst across the sky, then another, and another one farther to the left. For a moment it seemed to him as if the whole Milky Way were about to collapse.

Two arms slipped around Bernhard’s stomach, and hot breath swirled around his ear.

“What are you pondering about, my little professor?”

“About the void,” Bernhard whispered, leaning his head back on the other man’s shoulder. “And what it means when you see three shooting stars in a row.”

“Three? That means you have to think hard what to wish for. Because it will definitely come true.”

They stood for a while listening to the stillness, the floorboards creaking beneath their swaying bodies.

“So what did you wish for?” Edvard asked softly.

“I’m not allowed to say, otherwise it won’t come true.”

Bernhard turned around. The night cast a blue glow on Edvard’s face, which was clean, radiant and summery, as if it were full of colorful blossoms and the delicate smell of roses. A man much too beautiful to be real.

Bernhard stroked his short blond hair and held him by the neck. Edvard pressed against him. Every time they embraced, Bernhard had the feeling of merging with him a bit more.

“We’ve still got a few things to do.” Edvard gave him a quick kiss. “Our guests are coming soon.” Then he went back into the kitchen.

Bernhard watched as his lover strode into the hall: black, skin-tight jeans, thick-soled boots, a white satin shirt that hung out a bit on the left side over his studded belt. Bernhard was always touched when Edvard tried to seem casual for him, because it never really worked. His jeans were ironed; not a wrinkle in his shirt.

Although Edvard was rather petite, Bernhard often compared him to Obelix, who, having drunk a magic potion, couldn’t judge his own powers, or rather: who assumed everyone else possessed the same energy as he did. On the other hand, Bernhard often seemed like Obelix’ little dog Idefix: much too small, constantly afraid of being trampled. Who could keep up with so much imagination, euphoria, ecstasy, desire, sadness, compassion and love?

“Are you dreaming?”

Edvard stood like a silhouette in the brightly lit doorframe. Only the thin halo of light around his hair outlined him. His hand reached into the room and flipped the light switch.

“I never dream!” Bernhard responded, and pushed himself away from the windowsill.

At the clearance sale of the old airport Edvard had won a big neon sign in an auction. It said Riem in large black letters, with an arrow pointing towards the sky. After having an acrylic sheet mounted on it, he used it as a bar. Bernhard pushed the bar against the wall and plugged it in. The neon tubes flickered, then yellow light streamed out, offset by a harsh green glare that transformed the room into a Martian landscape.

“Can I put the magic dresser in the bedroom?” Bernhard began to lift the piece of former child’s furniture, but Edvard pushed him to away with dishwater-soaked hands.

“No!” he called. “Don’t touch it!”

The drawers were bursting with tarot cards, incense sticks, lotus seeds, perfumed oils, Indian medicine cards and other spiritual crap, as Bernhard called it. For Edvard it was holy.

“But if you keep it there, everyone will mess around with it.”

Edvard laid his hand on it protectively. “You think so? All right. But be careful.”

They lifted it and brought it into the bedroom. There, Edvard straightened the Celtic runes on the silk handkerchief that lay on top of it.

“Thank you!” He gave Bernhard a kiss, then looked around the living room. “Take the lamp from the bedroom and put it near the window so it’s not so gloomy when you turn off the ceiling light.” Then he disappeared into the kitchen. “And when you’ve got that taken care of, you could put these lilies on the bar.”

Bernhard stepped out into the long hall. Seven doors led to the bedroom, study, guest room, living room, kitchen, bathroom and stairwell. 3.750 square feet, if you counted the terrace as well. Bernhard still got lost in these rooms, he even had trouble in his own 650 square feet. Edvard might have been a head shorter than him but he needed five times as much space—for his aura, as he said. But it was probably more for his expansive emotional world, which would have felt restricted in the Sahara Desert.

Edvard rinsed champagne glasses with hot water, cleaning off the dreaded water stains with a towel made of Irish silk. Bernhard leaned against the doorframe, observing how meticulously he worked. This tidiness, this urge for perfection, for a superficial luster, was entirely foreign to him. But deep down Edvard was a wild bird, greedy as a predator, with cat’s paws. Perhaps it was this tidiness itself that kept him fenced in. It gave him a frame, a cage to run wild in.

He often thought about his lover, who lived in an entirely different word. For Bernhard he was a freely floating hot air balloon, and his love was the anchor Edvard could use to bind himself to him. But sometimes he escaped him, as he did now. Bernhard was standing less than three feet from him; he would only have had to reach out his hand to feel his warmth, his pulse, the storm of life that whirled around him like a cyclone. Nonetheless, Bernhard felt nothing but incredible desire.

The doorbell rang.

Birgit was sturdy and round. A black cape lay on her shoulders like an eagle’s wings, her gray, brown and black streaked hair was strewn with snowflakes, dripping down onto her warm face.

“Well, my darlings!” she greeted both of them, handing Edvard a mysterious package. “For both of you,” she said, pressing him tightly to her generous bosom.

She was almost seventy-five, but her face radiated the curiosity and alertness of a twenty-year old. Bernhard stretched out his hand to Edvard’s private oracle, whose deliberate nods were a necessary part of all Edvard’s major decisions.

“Well, well, well now. Surely you can give your old friend a kiss.” She held her cheek out to him, clapping him on the shoulder. “That’s better.” Then she looked at him with her deep, still eyes. “Congratulations. Two hundred and twenty-two days with this powder keg. Not easy.” She made a tragic pause and drew breath. “But don’t think you’re in the clear. You still have some things to learn. And if you’re not careful…” She tapped his chest with a gnarled finger and left him standing.

Bernhard understood little of what she said. But that was nothing new. Unlike Edvard, he had little use for this esoteric drivel. He didn’t believe in reincarnation, UFOs or unredeemed souls. Tarot cards, pendulums and astrology were nothing but hocus pocus to him, with a good splash of escapism mixed in.

“You’re early, Birgit. And everything else is late,” Edvard explained, pointing to the empty table. “The catering team is stuck in traffic.”

She took his head and pressed it against her cushioned shoulder to comfort him. Then the doorbell rang again; Bernhard opened the door.

“We’re terribly sorry, Mr. Bornheimer,” said a charming young man in a white suit, holding out a bottle of champagne to Bernhard. “The streets are smooth as glass, traffic is at a standstill. This bottle is on us, of course. I hope we’re not too late.”

“Much too late,” bleated Birgit. “I’m already starving to death.”

The young man looked deflated.

Edvard escaped from Brigit’s grasp: “Just joking.”

Bernhard gave him the bottle. Then large silver platters with pastries, salad and various bread-rolls were brought past him, covered by a fog of cold winter air. They placed the dishes on the long dinner table, one of the many pièces de resistance in Edvard’s private collection of unusual antiques: a breakfast table from an English monastery, dating back to the 14th century.

“You promised to get something simple. This must have cost a fortune.”

“Don’t worry about it.” Edvard squeezed his lover’s arm. “I’ll take care of it.”

“But Edvard. This was supposed to be our party.”

“Of course!” He stroked Bernhard’s forehead and opened the door, which had just rung again.

A whole flood of guests surged in; Edvard covered their frosty foreheads with kisses.

“You didn’t need to do this,” he said, holding a large packet up high.

“Open it and you’ll see how badly you needed it!” Some of Edvard’s former lovers enjoyed embarrassing him with their irreverence. Alfred was one of them. Bernhard preferred to avoid him, so he slipped out into the kitchen.

Excitedly, Edvard tore off the wrapping paper: a photograph of a young sailor in the bushes, and an enviable erection covering his face in semen.

“Oooooh!” Edvard squealed, laying a hand flat on his chest. “A real Pierre et Gilles! I can’t believe it. What have you done? This needs to go in a special place.” He looked around the walls. “There, above the dinner table. That would be wonderful,” he giggled.

Bernhard, drawn by the laughter, came from the kitchen carrying a tray. “Or maybe not,” Edvard said and put the picture down facing the wall.

Bernhard passed champagne around, the first glasses rang.

“Music. Where is the music?” Seconds later, Barbra’s voice was resounding from the speakers.

Bernhard opened the door for more guests. Jeans, striped shirts and light brown Doc Marten’s. As if cut from a mold, Bernhard thought, interchangeable, like thousands of others in this city. He hugged both of them, friendly but cool.

They filled the apartment slowly, and it grew warm. The floor sighed under so many feet. Edvard had invited a mishmash of people, lots of the kind that heteros typically branded as gay: the owner of a nail salon, whom they called Lipstick, the asparagus queen, who delivered asparagus to the markets in the spring, florists, dancers, actors, kindergarten teachers and the like.

Bernhard retreated between two tall bookshelves and observed them all. He had known many of them for months. He knew what films made them cry, what excited them, the way their apartments were decorated and what party they would vote for in the next election. Nevertheless, they remained foreign to him.

Edvard jumped among them like a bee from one bloom to the next; parties were the honey of his life.

“That face over there, is that an ex too?” He looked at the young man who wore his shirt open down to his pierced belly button.

But before he could open his mouth, another man answered for him. “You expect him to remember faces? Edvard only knows most of the guys here by their dicks.”

“Good thing for me. He definitely won’t forget mine,” the first one said.

“Right. Weren’t you the one who couldn’t get it up?” Edvard asked with a frown, and all three of them laughed.

“But come on, you’re not serious about Bernhard, are you?”

“Why not?” asked Edvard. His voice sounded annoyed.

“Well, you’ve never slept with the same guy twice. And now someone like *her*?”

“You’re exaggerating,” the other one clarified. “He did it three times with me.”

“Only because you had tied me to your bed,” Edvard joked.

“I can’t imagine it otherwise. Anyone would sleep with him more than once has either never seen a real dick, is homeless, or already dead,” one of them said to the other. Edvard laughed.

“Oh, how very witty. I didn’t know an old frump like you could even form a sentence you haven’t read on a bathroom wall somewhere.”

“Come on, girls. Don’t start squabbling about Bernhard. I’m very serious about him and there’s nothing to be done about that. So that’s that!”

“Congratulations.” Gerhard shook Bernhard’s hand.

“Thank you.” Bernhard clinked his glass against his.

“You should consider yourself fortunate. Other than you guys, every relationship I know is in crisis. Most of them haven’t even been together as long as you two.”

“How does it feel to be the lucky one?” Gabi clinked his glass as well.

She was expecting something like “happy,” “content,” or “fantastic,” but Bernhard answered: “two hundred and twenty-two days aren’t exactly eternity, are they?”

“I’m ready for another round!” She waved her empty glass and entered the party again with Gerhard on her arm.

“Awesome vibe,” said Florian.

“Yeah, I guess.”

“I think it’s great that you’re sticking together like that.”

Bernhard looked past him at his lover. Their glances met. Edvard paused briefly on the way to his next conversation partner, holding Bernhard’s eyes captive. They were shy, open, but like a camera lens they were ready to close up any moment. No one, not even Bernhard himself, knew what would happen then.

“You’re really a dream couple, you know?”

“There’s no such thing as dream couples, Florian. If a relationship works, it’s only because you want it to. Dreams are random, unpredictable. And if you try to grasp them, they slip away. You can only find footing in reality.”

“I guess you’re not a born romantic,” Florian said, disappointed.

“Don’t be so sure.” Edvard had joined them. “Bernhard is unbelievably romantic. He just doesn’t like to admit it.”

“No, I’m not. I’m a realist. I don’t think anything of dreams.”

“Yes, Mr. Einstein,” Gabi joked, returning with a full glass.

“Einstein was the purest dreamer. He came up with his theory of relativity while he was sitting in front of a blazing fire in the hearth. What’s more romantic than that?”

“I never claimed I was Einstein.” Bernhard’s pupils contracted. “I just don’t think much of dreams. I don’t dream, I’ve never dreamed, and I don’t want to either.”

Edvard hung on his boyfriend’s neck, marveling at him. If he weren’t already his, he would have fallen in love that very moment.

“Look at those lovebirds,” Gabi chirped.

Bernhard pulled his head from his lover’s clutches. “I’ll go open another bottle.”

“He still gets a bit embarrassed when other people are around,” Edvard whispered, looking after him yearningly.

“You don’t find him a bit aloof?” Gabi asked. Edvard’s face showed that he did not like the question at all.

“He’s so wonderful, my little professor.”

“He doesn’t have much imagination,” Florian asserted.

The music broke off, and Heiner’s voice rang out for attention. “Time for presents!”

Ursl dragged a big silver package down off the coat rack.

“How did you smuggle that into my apartment?” Edvard wanted to know.

She lifted her finger to her lips and pointed to the pink ribbon holding it together. “It’s from all of us. May your love last forever.”

Edvard’s eyes grew moist. He threw himself about her neck and blew kisses to the others. Then he set about opening the package. As soon as he had taken off the ribbon and pushed the paper aside, an over six-foot tall rubber man was catapulted out of the box. He was equipped with every male attribute, truly every one, and nothing done by half measures.

“Big Jim, large as life! I can’t believe it. You’re so sweet. But where…?”

“He made it.” Ursl pulled Harald by the hand up to the front.

“Custom-built,” he said, and blinked shyly, though radiating pride.

“A true masterpiece,” Edvard felt the doll’s smooth skin. “Who was the model for him?”

“His name is Georg,” Harald admitted, growing red.

Bernhard bent over the box and tried to figure out how to inflate the doll. “The mechanism is really simple,” Harald boasted. “Very simple.”

Edvard was overwhelmed. “I’m so grateful. You are my darlings.” He lifted the glass.

“To the two of you,” his friends answered in chorus, while their glasses clinked hollowly. “To long, intense love.” “To lots of children.” “To a happy life.”

“Sweet,” Edvard said. “I’m glad you all took the time so close to Christmas. You’re just wonderful.”

Bernhard sunk his head. Now it was his turn to say something, but what? “To you all!” he said drily.

All eyes were on the two of them. Edvard, visibly moved, reached for Bernhard’s hand.

“My dears,” he began with a broken voice. He flourished his champagne glass to ensure everyone’s attention. “My dears. I would like to seize this opportunity to tell you all something. Today Jupiter, Ruler of Happiness, reached his highest point in our relationship horoscope. That’s why I’d like you all to be here, our family gathered together…” he put down his glass and pulled a small black box from his pants pocket, “…when I propose to my lover,” and put a ring on Bernhard’s finger.

Suddenly it was very quiet, so quiet that Bernhard heard the blood rush in his ears. He looked at the piece of jewelry: a diamond and a ruby, held in two golden hands. The ring shone brightly, but there was something dark and magical about it. Heat radiated from it, as if all the light in the city were concentrated within it.

Bernhard vibrated. Suddenly there was something light in his chest, an unknown warmth. His eyes burned. As he rubbed them, he noticed they had grown moist. He would have liked to hug someone, but at the same time he wanted to disappear.

Their friends’ faces looked at him expectantly. He needed to react somehow, but he couldn’t think of anything. So he gave Edvard a shy kiss.

A tear rolled down Willi’s cheek, Uli and Dieter reached for each other’s hands and Florian began to rummage around for his handkerchief. Within this impassioned atmosphere, Birgit stood still, holding her hands clasped in front of her chest. Her eyes were large and deep.

The glasses clinked again, somewhat more lightly this time. Andreas demanded: “A waltz! A waltz!” and the guests clapped encouragingly. Ursl put on a wedding waltz, and groom and groom began to dance.

“Say something,” Edvard begged, but Bernhard shook his head. “Do you like it?” Bernhard nodded.

Edvard spun him around, Bernhard missed a step and stumbled.

“You’re really pale. Are you all right?”

“I’m dizzy. Maybe I drank too much.”

Edvard lead his lover past dancing couples and giggling guests into the bedroom. Bernhard felt as if they were staring at him.

“What’s wrong?”

Bernhard’s stomach cramped, his throat felt tight, something tugged at his chest. And that ring. It glowed so warmly that he was afraid it would burn him. His knees gave out; he sat on the edge of the bed. Edvard stood before him and drew Bernhard’s head to his narrow, bony thighs.

“I’m afraid,” whispered Bernhard.

“Afraid? Of what?”

“I don’t know.” He clasped Edvard’s thighs, pulling him closer. What were these feelings? Where did they come from? “Hold me!”

“Don’t be afraid. I’m here with you,” Edvard whispered, giving him a kiss.

Bernhard wrapped himself closer around his boyfriend, clasping him tightly, as if he were in danger of losing Edvard forever.

Edvard snuggled up against him. His breath quickened. He pulled his lover’s sweater over his head. On the surface, Bernhard always seemed so stiff and hard, as if he were surrounded by a wall. No one would have believed what he was hiding under his old-fashioned clothes: a chest as gentle and fragile as dragonfly wings and skin as soft and smooth as a calm ocean, overgrown with fine, light hair.

They fell back on the bed. Edvard lay on his boyfriend; his heart began to gallop. Blood streamed through his body, and within seconds his pants began to tent. He wanted Bernhard, he wanted him here and now.

Swiftly and eagerly, he opened Bernhard’s belt; Bernhard submitted, and was naked in no time. While Bernhard’s eyes stared at the ceiling, Edvard grasped greedily at his flesh. Then Bernhard held his breath.

“Bernhard? Bernhard!”

A black cloud formed in the room. It smelled musty. Bernhard’s hair stood on end, his eyes opened wide. Horror rose up inside him. An icy shudder made him jump up and look for his clothes.

“Hey, what’s wrong?”

Frantically, he put on his pants and sweater, not answering. Edvard leapt after him, embraced him, looking into his distraught face. Bernhard’s eyes were full of panic—and something else, something unrelenting… like hatred.

“Bernhard!” called Edvard. These eyes made him afraid. He let go of him, terrified.

Bernhard ran out; the door to the living room slammed, and Edvard heard the guests grow quiet. He stood there, beaten down. Since the day that strange man had sold him the ring, he had been convinced it would seal their relationship more tightly. And Jupiter reigned over this party, he brought happiness, not discord and fear. Something was going wrong here. But what?

“He has a bad headache. He needs a little peace and quiet,” Edvard explained, smiling as much as he could, when Birgit popped her head around the door.

“Trouble in the air?” Andreas asked over her shoulder. Someone pulled him on the arm and hissed: “Just shut up, you awful gossip!”

“The young couple just needs to sow a few wild oats,” another guy said.

Birgit laid a fleshy hand on Edvard’s arm. Heiner sat next to him on the bed, and Birgit retreated. “Must be a really bad headache?”

“You want to say you told me so. You can spare yourself the trouble,” Edvard said resignedly.

“Would I ever do such a thing to you, darling?” Heiner fluttered his eyelids and lowered his head to his chest in shame.

Edvard lifted his head wearily. His eyes were dull, the gleam of his white-blond hair was extinguished. He couldn’t even laugh anymore.

“Come on, have a drink, then explain to me again what you see in this guy.” He poured out a large glass of vodka and held it under Edvard’s nose.

Edvard took the glass and placed it on the nightstand. “You’ve never tried to see the person behind the disheveled hair.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about at all. It just seems to me that at some point or other, your math teacher got rid of his emotions. Or do you not find him a bit stiff?”

“He’s not stiff. He just doesn’t feel the need to rub other people’s noses in his feelings.”

“Would it be rubbing anyone’s nose in them to smile at his friends every now and then?”

Edvard looked into the eyes of the man across from him.

“He doesn’t even go out to bars.”

“There are other reasons for that.”

“Yeah? What then?”

“Bernhard doesn’t care for organized identity.”

“Oh, that sounds lovely! Like organized crime.”

“Nonsense! He just doesn’t like queens, that’s understandable.”

“Look who’s talking now! Do I need to remind you of your performances as Sister Edith?”

“Oh come on, that was something else.”

“Yeah, your nun striptease set off what may very well be the biggest orgy in the history of Munich.”

“That was just a bit of fun.” Edvard took a sip of vodka. His eyes grew wide, he swallowed loudly and sat down.

“In my day, this sort of thing wouldn’t have happened,” Heiner said, looking out the window. “Today anyone can turn gay. That’s the one thing that liberation has brought us.” He shook his head.

Edvard ignored his friend’s ironic commentary. “When I was a kid I always felt that I had a brother my parents were hiding from me. I was quite certain of it. Then when I saw Bernhard for the first time, I was convinced it was him. We searched for one another for thirty-five years. Suddenly my life was complete. There was nothing missing anymore, do you understand?”

“You’re not exactly identical twins!”

“Bernhard has very special qualities: he is intelligent, he doesn’t value all that insincere consumer-speak. He knows what’s going on in the world.”

“You’re not trying to say he’s got both feet on the ground?”

“All right. He’s an absent-minded professor. But if you really want to know, that makes him more loveable to me.”

Heiner lifted his eyebrows.

“After all, we’ve been together seven months. Who in our group can match that?”

“It’s not about setting records.”

Edvard looked Heiner in the eyes for a long time before saying: “I want a serious relationship. I’m sick of waking up in a new bed every morning.”

“The question is, have you picked the right one?” Heiner asked.

Edvard stared at him. “What are you trying to say?”

“I’m trying to say that there are people who split up after thirty years of marriage, after fifty even. Seven months, what’s that?”

“Seven months are nothing. You’re right about that. But the fact that we met is no coincidence, I know it. That’s why I won’t give up.”

“What are you going to do?”

Edvard didn’t answer.

“Hello? Is anyone in there?” Heiner tapped him on the forehead.

Edvard turned to him: “I’m going to woo my prince back.”

3.

Roswitha hardly dared to breathe. In sleep, his angular lower jaw relaxed, his narrow lips swelling to fleshy hills beneath his black mustache. Her hand moved, trembling, over to his chest again and again, but each time she felt the wiry hair on his body, her hand pulled back. Then she would lie on her back and stare at the dark ceiling, hoping to finally find sleep. But every time she shut her eyes, she would open them again right away, turning her head towards him to make sure he was still there. This was how it had been for weeks.

Four fifty-two. Eight minutes to five. Her feet groped for her pink slippers. She got up, her dressing gown trailing behind her like a cloud of perfume. Fred remained in bed, lying as if tossed there. He had been tossing and turning under the blanket. His ass lay free, round and hard, tugging at her desire. If she covered him up, she would be able to touch him again. But she hesitated, and didn’t do it in the end. Instead she steered herself into the kitchen, where she carried out her morning rituals, almost without a sound: putting water in the coffee machine, a filter, coffee powder. It had all been rehearsed a thousand times. She didn’t need to think about it at all. Wipe off the yellow tablecloth, put out the brown earthenware plates, take knives and coffee spoons out of the drawer: but for the past four weeks she had been doing this for two, not just for herself alone. It was a ceremony she conducted as if in a trance.

Then she turned on the shower, hung her nightshirt on the door next to his bathrobe, brushed her hair and put a shower cap over it. The neon light shining off the bright green tiles made her face look pale, casting a black shadow on her deep eye sockets. She looked in the mirror: a few more wrinkles.

In the shower she lathered herself up with musk gel, picked up the loofah, which hung from a hook in the shape of a splayed foot, and scrubbed her body. Routines made life simpler; she had learned this from her mother. She rarely deviated from them, not even on weekends. But today she desperately needed something new. Something absolutely had to change. She dried herself off and slipped into her underwear. She hesitated with her sweater. A winter pattern of silver beads on black angora? No!

The machine had stopped bubbling. Roswitha set the sweater down on the table, poured some of the coffee into a mug, and the rest into a beige thermos patterned with flowers. With a dash of condensed milk, she lightened the liquid up, pulled the wool curtain aside and looked out. Snow. Snow again. Flakes as large as playing cards pranced towards the ground, where unrelenting car tires pressed them together into hard sheets. Today, it would take her longer to get to the other end of the city.

This early in the morning, it was usually still quiet in their building. A drain gurgled, a flushing toilet sent water gushing through the pipes. Heels clacked down the dark-grey marble stairs, the door to the building fell shut.

Roswitha rinsed and dried the mug in the sink, then paused. Something was missing. She folded a red napkin into a heart and placed it in his mug. Finished!

Then she took the sweater and went into the bedroom. Fred was tossing in bed, mumbling and sighing deeply. He had slid over to her side. If she were still lying there, his arm would be around her now. Blood rushed to her lower body, her pulse throbbed in her throat to imagine it, but there was no time for that now. She went to the dresser and pulled out a red blouse and a cardigan of the same color. When she turned around, his clothes caught her eye: a leather jacket, worn-out jeans and cowboy boots with spurs lay next to the bed. What if she hid them? Then she could be certain he would still be there in the evening when she came back from work.

In the kitchen, she left the light on; in the bathroom she turned it off. Then she slipped her keys into her pocket, reached for her scarf and left.

Her small Fiat was waiting at the end of the street. When the weather was damp, it would hardly start at all. Fred claimed it was because it was so old. And he would know: he was a mechanic after all. But Roswitha couldn’t afford to buy a new car right now. She had just invested a lot of money in the French bed, and she had opened up an account for Fred so he wouldn’t have to ask her for money.