Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

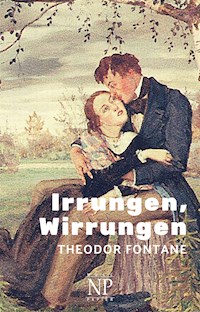

- Sprache: Englisch

Lene is an orphaned seamstress; Botho is a nobleman and an officer in one of the Prussian army's most glittering regiments. But whatever their differences of class and education, their hearts are equal to each other. Over the course of a summer in 1870s Berlin, they enjoy a clear-eyed, tender love affair, in spite of the judgements and warnings of those around them.The end comes all too soon, and Botho marries a wealthy cousin. When, years later, Lene too has an opportunity to marry, her ex-lover must choose between holding on to regret or letting go of the past - along with the possibility of getting Lene herself back.Full of tender irony and vivid evocations of a quickly expanding Berlin and its bucolic surroundings, this small masterpiece gives us a love story poised between the strict social codes of the 19th century and the sometimes bewildering freedoms of the 20th.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘No writer of the past or the present awakens in me the sympathy and gratitude, the unconditional and instinctive delight, the immediate amusement and warmth and satisfaction that I feel in every verse, in every line of one of his letters, in every snatch of his dialogue’

THOMAS MANN

‘A master of characterization and delicate plotting’

NEW YORKER

‘In the first rank of German writers’

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS2

3

4

ON TANGLED PATHS

THEODOR FONTANE

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY PETER JAMES BOWMAN

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS

Contents

Acknowledgements

This translation of Irrungen, Wirrungen is based on the edition of the novel published by Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich in 1980. It has appeared as an Angel Classic and a Penguin Classic, and I am grateful that it is now among the Pushkin Press Classics with two other Fontane titles. I should like to thank Antony Wood for his extensive editorial input and Rudolf Muhs for checking the accuracy of the afterword.

p. j. b. 8

1

At the point where the Kurfürstendamm intersects the Kurfürstenstrasse, diagonally across from the Zoological Gardens, there was still, in the mid-eighteen-seventies, a large market garden running back to the open fields behind; and in it stood a small, three-windowed house with its own little front garden, set back about a hundred paces from the road that went by and clearly visible from there despite being so small and secluded. However, the other building in the market garden, indeed without doubt its main feature, was concealed by this little house as if by the wings of a stage set, and only a red- and green-painted wooden turret with the remains of a clock face (no trace of an actual clock) under its pointed roof suggested that there was something hidden in the wings, a suggestion confirmed by a flock of pigeons fluttering up round the turret from time to time and, even more, by the occasional barking of a dog. The whereabouts of this dog eluded the viewer, although the front door on the far left stood open all day long, affording a glimpse of the yard. There was in general no apparent intention to hide anything, and yet anyone who passed that way at the time our story begins had to be content not to see beyond the little three-windowed house and a few fruit trees standing in the front garden.

It was the week after Whitsun, when the dazzling light of the long days sometimes seemed never-ending. But today the sun was already behind the Wilmersdorf church steeple, and the rays that had beaten down all day were now replaced by evening shadows in the front garden, its almost fairy-tale calm exceeded only by the calm of the little house, in which old Frau Nimptsch and her foster-daughter 10 Lene lived as tenants. Frau Nimptsch herself was, as usual, sitting by the large but barely one-foot-high hearth in her front room which occupied the whole width of the house, and she crouched forward gazing at a sooty old kettle whose lid kept rattling even though steam was already billowing from the spout. The old woman stretched both hands out to the glowing embers and was so absorbed in her thoughts and daydreams that she did not hear the door out into the hallway opening and a sturdy female figure bustling into the room. It was only when the latter had cleared her throat and addressed her friend and neighbour (our Frau Nimptsch) warmly by name that she turned towards the back of the room and, just as amiably and with a touch of mischief, replied, ‘Ah, Frau Dörr, my dear, how good of you to drop by, and from the “castle” too, ’cos it isa castle an’ always will be, with its tower an’ all. Now sit yourself down … I just saw your dear husband goin’ off somewhere. Course – it’s his skittles night.’

The visitor so warmly greeted as Frau Dörr was not merely sturdy but of decidedly imposing proportions, and gave the impression of being a kind-hearted, dependable soul but also a person of distinctly limited intelligence. This clearly in no way troubled Frau Nimptsch, who repeated, ‘Yes, his skittles night. But what I’ve been meanin’ to say, my dear, is that your husband can’t go about in that hat no more. It’s worn smooth an’ a proper disgrace to look at. You ought to take it off him and put a new one out. He mightn’t even notice … Now pull up a chair, Frau Dörr, my dear, or better, sit on that stool over there … As you see, Lene’s gone out an’ left me on my own again.’

‘So he was here, then?’

‘Certainly was. An’ they’ve gone out Wilmersdorf way. You never meet no one on that path. But they should be back any minute.’

‘Well, I’d best be goin’, then.’

‘No need, Frau Dörr, my dear. He won’t stop. An’ even if he does, he’s not, you know, like that.’

‘I know, I know. An’ how do things stand?’

11 ‘Well, what can I say? I think she’s gettin’ ideas, even if she won’t admit it, buildin’ her hopes up.’

‘Dear oh dear,’ said Frau Dörr, as she drew up a slightly higher stool than the footstool she had been offered. ‘Dear oh dear, that isbad. When they start gettin’ ideas, that’s when things turn bad. Sure as night follows day. You see, Frau Nimptsch, my dear, I was in the same boat, but I never got no ideas. And ’cos of that it was quite a different kettle of fish.’

She could see that Frau Nimptsch did not quite grasp her meaning, and so went on, ‘It was ’cos I never got no ideas into my head that it all worked out so smooth an’ easy, and now I’ve got Dörr. It’s not much, I know, but it’s respectable, and you can show your face anywhere. And that’s why I went to church with him and not just the registry office. If you don’t do it in church they’ll always talk.’

Frau Nimptsch nodded, but Frau Dörr repeated, ‘Yes, in church. St Matthew’s it was and Büchsel* took the service. But you see, what I really meant to say, my dear, is that I was actually taller and more takin’ than Lene, an’ if I wasn’t prettier (’cos you can’t really know, and tastes do vary), well, there was a bit more of me, which there’s some as like. No doubt about it. But even though I was fuller, you might say, with more substance, an’ even though there was somethin’ about me, p’raps – yes, there definitely was somethin’ about me – still I was always quite straightforward, almost a bit simple. An’ as for him, my count, fifty years old if he was a day, he really was a simple soul, always as cheery as can be an’ indecent with it. An’ if I told him once I told him a hundred times: “No, no, Count, thatI won’t have, I draw the line at that…” And that’s how the old ’uns always are. I tell you, Frau Nimptsch, my dear, you just can’t imagine it. Dreadful it was. An’ when I look at Lene’s baron I still feel right ashamed of 12 what mine was like. An’ as for Lene, she’s no angel, I don’t suppose, but she’s a tidy, hard-workin’ girl, can turn her hand to anythin’, an’ with a sense of what’s right and proper. An’ you see, my dear, that’s the sad thing about it. The ones that gad about all over the place, they fall on their feet and never come to grief, but a good girl like her that takes it all to heart an’ does it all for love, that’sbad … Or maybe it isn’t; after all you only took her in, she’s not your own flesh and blood, an’ maybe she’s a princess or somethin’.’

Frau Nimptsch shook her head at this notion and seemed about to answer. But Frau Dörr had already stood up and, looking down the garden path, said, ‘Lord, here they come. And not even in uniform, jus’ a plain coat an’ trousers. But you can tell just the same! An’ now he’s whisperin’ in her ear, and she’s laughin’ a bit to herself. Oh, she’s gone all red … And now he’s leavin’. An’ now I think … yes, he’s turnin’ round again. No, no, he’s just givin’ her another wave, and she’s blowin’ him a kiss … That’s the way. Yes, that’s what I like to see … No, not a bit like mine, not a bit.’

And Frau Dörr went on talking until Lene came in and greeted them both.

* Carl Albert Ludwig Büchsel (1803–89), prominent Lutheran clergyman known for his memoirs and published sermons.

2

The following morning the sun, already quite high in the sky, shone down on the yard of the Dörrs’ market garden and illuminated a whole cluster of buildings, among them the ‘castle’ of which Frau Nimptsch had spoken the previous evening with a trace of mockery and mischief. Yes, that ‘castle’! At dusk its bulky silhouette really could make it pass for something of the sort, but today, in the pitilessly bright light, it could be seen only too clearly that the entire edifice, painted up to the top with Gothic windows, was nothing more than a wretched wooden box, into the two gable ends of which a straw- and clay-filled timber framework had been inserted, forming a comparatively solid structure that supported a pair of attic rooms. The rest of the space had a simple stone floor, and from it a tangle of ladders led first to a loft and then higher up into the turret that served as a dovecote.

Earlier, in the pre-Dörrian period, the whole of this huge wooden box had been used as a barn for storing beanpoles and watering cans, and perhaps also as a potato cellar; but from the time, umpteen years ago, when the market garden was purchased by its present owner, the house itself was let to Frau Nimptsch and the Gothic-painted box fitted up by the addition of the aforementioned two attic rooms to make a living space for Dörr, then a widower – a most primitive arrangement which his remarriage soon afterwards did nothing to alter. In summer this almost windowless barn with its flagstones and its coolness was not a bad place to live, but in wintertime Dörr and his wife, together with a twenty-year-old, slightly mentally deficient son from his first marriage, would simply have frozen to death had it not been for the two large hothouses on the other side of the yard. 14 It was exclusively in these that all three Dörrs spent November to March; but in the more clement months too and even at the height of summer – except when shelter was needed from the sun – family life was carried on mainly in and around these hothouses, because here everything lay most conveniently to hand: here were the shelves and stands on which flowers from the hothouses were placed each morning to freshen in the open; here was a shed for the cow and the goat and a kennel for the dog that pulled the cart; and from here a pair of hotbeds, a good fifty paces long with a narrow path in between, stretched to the large vegetable garden further to the rear.

This vegetable garden was not exactly neat and tidy, partly because Dörr was not given to order, but also because he had such a strong passion for chickens that he allowed these favourites of his to peck around everywhere without regard to the damage they caused. Not that this damage was ever great, for apart from the asparagus beds his market garden contained nothing of the choicer sort. Dörr held that the commonest things were also the most profitable, and therefore grew marjoram and oregano, but most of all leeks, reflecting his abiding principle that the true Berliner requires only three things: wheat beer, Gilka Kümmelschnapps and leeks. ‘With leeks,’ he would regularly conclude, ‘you always get your money’s worth.’ He was altogether quite a character, with a most independent outlook and a complete disregard for what other people said about him. His second marriage was of a piece with this, a marriage of inclination to which he had been prompted in part by the notion of his wife’s especial beauty, her earlier relationship with the count, rather than damaging her in his eyes, having on the contrary weighed decisively in her favour by furnishing conclusive proof of her irresistibility. And although this could fairly be described as an overestimation, it was no such thing coming from someone like Dörr, to whom nature had been exceptionally ungenerous as far as outward appearance was concerned. A thin man of medium height with five strands of grey 15 hair across his head and brow, he would have cut an utterly commonplace figure had it not been for a brown pockmark between his left eye and temple which made him look distinctive. And on this account his wife was not wrong when she said from time to time, in her own uninhibited style, ‘All shrivelled up he is, but from the left side he does look a bit like a Borsdorf apple.’*

The description captured him to a nicety and would have identified him to anyone but for the fact that day in, day out he wore a linen cap with a large peak pulled down so far over his face as to hide both the ordinary and the singular aspects of his physiognomy.

And thus he stood again the day after the conversation between Frau Dörr and Frau Nimptsch, his peaked cap pulled over his face, in front of a flower-stand supported against the first hothouse, setting aside various pots of wallflowers and geraniums that were to go to the weekly market the next day. All of these plants had simply been transferred to their pots rather than grown in them, and he lined them up before him with particular satisfaction and delight, already laughing in anticipation at the well-to-do housewives who would come along on the morrow, haggle their usual five pfennigs off the price, and still end up being gulled. This counted among his greatest pleasures and was the chief purpose to which he applied his intellect: ‘That bit of cussin’ … wouldn’t I love a chance to overhear it.’

He was just saying this to himself when from the direction of the garden he heard the barking of a little cur interspersed with the desperate crowing of a cock, unless he was quite mistaken his cock, his favourite of the silver plumage. And directing his gaze towards the garden he saw that a group of chickens had indeed been scattered, while the cock had flown up into a pear tree, from which he called uninterruptedly for help against the yapping dog below.

16 ‘Blast it!’ cried Dörr furiously, ‘that’s Bollmann’s again … he’s got through the fence again … I know what I’ll …’ And quickly putting down the potted geranium he was inspecting, he ran towards the kennel, grabbed the chain-clasp and released the large cart-dog, which shot straight over to the garden like a creature possessed. However, before he could reach the pear tree ‘Bollmann’s’ took to its heels and vanished under the fence to the open ground beyond. At first the fox-coloured cart-dog bounded along behind, but the gap under the fence, just the right size for the affenpinscher, denied him exit and forced him to desist from his pursuit.

Just as unsuccessful was Dörr himself, who had meanwhile arrived on the scene with a rake and now exchanged looks with his dog. ‘Well, Sultan, no luck this time.’ At which Sultan made his way slowly back to his kennel, looking abashed as if he had detected a hint of reproach in this remark. For his part Dörr stared after the affenpinscher for a while as it raced along a furrow in the open field, and then said: ‘I’ll be damned if I don’t get myself an air gun from Mehles’ or somewhere. And then I’ll quietly do away with the brute and no one’ll give two hoots, leastways not my own hens and cock.’

For the moment the latter appeared to entertain no thought of observing the silence expected of him by Dörr, continuing instead to make the greatest possible use of his voice. And in doing so he proudly threw out his silver neck, as if to show the hens that his flight into the pear tree had been either a carefully considered ploy or a mere whim.

But Dörr said: ‘There’s a cock for you. Thinks the world of himself, but he’s no big hero after all.’

And with that he walked back to his flower-stand.

* Originating in Borsdorf near Leipzig and often exhibiting small brown marks.

3

All this had been observed by Frau Dörr, who was cutting asparagus, but she did not pay much attention because the same course of events was repeated nearly every other day. Instead she carried on working, and only when even the closest scrutiny of the beds revealed no more ‘white-tips’ did she give up her search. Then she hooked the basket over her arm, placed her knife inside it, and, driving a few stray chicks before her, walked slowly towards the central path through the garden and from there to the yard and the flower-stand, where Dörr had resumed his preparations for market day.

‘Well, my little Susel,’ he greeted his better half, ‘so that’s where you are. Did you see? That beast of Bollmann’s was here again. He’s got a nasty accident comin’ his way, an’ then I’ll roast all the fat there is out of him, an’ Sultan can have the crispy bits … An’ you know, Susie, dog fat …’ But just as he seemed about to dilate on the method of treating gout he had favoured for some time, he noticed the basket of asparagus on his wife’s arm and checked himself. ‘Now, give us a look, then. Any good?’

Frau Dörr held out the barely half-full basket to him. He shook his head as he ran its contents through his fingers, for it was mostly thin stalks with a lot of broken pieces mixed in.

‘Listen, Susel, there’s no denyin’ it, you’ve got no eye for asparagus.’

‘I have too, but I can’t work miracles.’

‘Well, let’s not argue, Susel; that won’t give us no more. But you could starve to death on that.’

‘I don’t think so. Leave off your talk for a change, Dörr. They’re in the ground, aren’t they, an’ it makes no odds if they come out today or tomorrow. Just needs a nice heavy shower like before Whitsun, 18 and then you’ll see … An’ it’ll rain all right. The water butt’s started smellin’ again and the big spider’s crawled into the corner. But you want it all every day, and that’s askin’ too much.’

Dörr laughed. ‘Well, tie it all up nice and tight, the scrubby bits too. You can always knock a bit off.’

‘Don’t talk like that,’ his wife interrupted. She was forever getting irritated at his meanness, and she tweaked his earlobe in her customary way, which he always took as a sign of affection, and then made her way to the Castle, where she meant to make herself comfortable in the stone-floored area and tie up her asparagus bundles. But hardly had she moved the stool that always stood ready there out towards the doorway when she heard a rear window of Frau Nimptsch’s little three-windowed house diagonally opposite being opened with a vigorous push and then put on the latch. At the same time she saw Lene, wearing a loose, lilac-patterned jacket over a frieze skirt and a little bonnet on her ash-blond hair, giving her a friendly wave.

Frau Dörr returned the greeting with equal warmth and then said, ‘That’s right, always open your windows wide, Lene, my poppet. It’s gettin’ hot already. It’ll turn before the day’s out, mind.’

‘Yes, and mother’s already got her headache from the heat, so I thought I’d rather do the ironing in the back room. It’s nicer here anyway. You never see a soul at the front.’

‘You’re right,’ answered Frau Dörr. ‘Well, I’ll just shift myself a bit closer to the window. Makes the work go quicker if you’ve got someone to talk to.’

‘Oh, that really is kind of you, Frau Dörr. But here by the window you’ll be right in the sun.’

‘That won’t harm, Lene. I’ll fetch my market umbrella. It’s an old thing, full of patches, but it still does the job.’

And not five minutes later the good Frau Dörr had dragged her stool over to the window and settled herself there under her standing umbrella, as comfortable and self-possessed as if she were on the 19 Gendarmenmarkt.* Inside, meanwhile, Lene had placed her ironing board on two chairs moved up against the window, and now stood so close to the other woman that they could easily have reached out and shaken hands. The iron went briskly back and forth, and Frau Dörr too was busy with her sorting and binding. Now and again she raised her eyes from her work, and through the window she saw the little stove that supplied freshly heated slugs for the iron glowing on the far side of the room.

‘Could you just give me a plate, Lene, a plate or a bowl.’ Lene promptly brought the desired article to Frau Dörr, who then filled it with the broken bits of asparagus she had put in her apron as she sorted through the stalks. ‘There, Lene, that’ll do for some asparagus soup. An’ it’s as good as the rest. People always want the tips, but that’s daft. Same with cauliflower. The flower’s what they want, always the flower, they can’t get it out of their minds. But it’s the stem that’s the best bit. That’s where the goodness is, an’ it’s the goodness that counts.’

‘Lord, you’re always so kind, Frau Dörr. But what will your old man say?’

‘Him? Who cares what he says, my pet? It’s all talk with him. He’s always after me tyin’ in the scrubby stuff as if it was the real thing, but I don’t like that sort of trickery, even if the broken bits without tips do taste as good as the ones with everythin’ on. You should get what you pay for, an’ it makes me angry that someone like him that’s doin’ very nicely is such an old skinflint. But market gardeners are all the same, always graspin’ for more an’ never satisfied.’

‘Yes,’ Lene laughed, ‘he is stingy and a bit odd in his ways. But still a good husband, I’m sure.’

20 ‘Yes, my pet, he wouldn’t be too bad, an’ even his stinginess I could live with – it’s better than blowin’ it all – if only he wasn’t so affectionate. Never leaves me alone – you wouldn’t believe it. An’ just look at him. He really is a poor figure of a man, an’ all of fifty-six too, or maybe more, ’cos he tells lies when it suits him. And there’s no way I can stop him, no way at all. I keep tellin’ him about people gettin’ strokes an’ I point them out, hobblin’ along with crooked mouths, but he just laughs and won’t believe it. It’ll happen, mind. Yes, my pet, I’m quite sure it’ll happen. Maybe quite soon. Still, everythin’ comes to me in his will, so I’ll say no more. As you make your bed, so you must lie on it. But what are we doing talkin’ about strokes and Dörr with his bandy legs. Lord, there’s a very different sort of man, as tall an’ straight as a spruce tree, isn’t there, Lene, my poppet?’

At this Lene grew even more flushed than she already was. ‘This slug’s gone cold,’ she said, and stepped back from the ironing board and went over to the cast-iron stove to shake the slug out onto the coals and take up a new one. It was all the work of an instant. Then with a deft movement she slid the new red-hot slug from the end of the poker into the iron, shut its little panel back up, and only then observed that Frau Dörr was still waiting for an answer. To make sure, however, the good woman asked her question again and then added, ‘Is he comin’ today?’

‘Yes, at least he said he would.’

‘Tell me now, Lene,’ continued Frau Dörr, ‘how did it start? Mother Nimptsch never says nothin’, an’ if she does it’s all vague, neither one thing nor another. Only tells half the story an’ gets the whole thing mixed up. So you tell me. Is it true it was in Stralau?’

‘Yes, Frau Dörr, it was in Stralau, Easter Monday, but already so warm it could have been Whitsun, and because Lina Gansauge wanted to go rowing we found ourselves a boat, and Rudolf – you probably know him, a brother of Lina’s – well, he took the oars.’

‘Rudolf. Lord, but he’s only a boy.’

21 ‘I know. But he reckoned he knew what to do, and kept saying, “Sit still, girlies, yer rockin’ de boat” – he’s got such a terrible Berlin way of talking. But we were doing no such thing because we could see straight away that his boating skills weren’t up to much. After a bit, though, we forgot to worry and just let ourselves drift along, bantering with people who passed by and splashed us. In one of the boats going in the same direction as ours there were a couple of very fine gentlemen who kept waving at us, and in our high spirits we waved back, and Lina even shook her hanky and acted as if she knew them, which she didn’t; she was just showing off because she’s still so young. And while we were laughing and joking and just toying with the oars, suddenly we saw the steamer coming at us from Treptow. As you can imagine, dear Frau Dörr, we had the shock of our lives, and in our terror we shouted to Rudolf to row us out of the way. But the boy lost his head and just rowed us round in circles. By now we were screaming and would certainly have been hit if the two men in the other boat hadn’t immediately taken pity on us in our danger. With a couple of strokes they were alongside us, and while one of them pulled our boat firmly and quickly over with a hook and attached it to theirs, the other rowed us all clear of the swirling water – just for a moment it seemed that the big wave coming at us from the steamer might overturn us. The captain actually wagged his finger at us (which I noticed for all my terror), but then it was all over, and a minute later we’d got to Stralau, and the two who’d so kindly rescued us jumped ashore and gave us their hands like real gentlemen to help us get out. And so there we were standing on the landing-stage next to Tübbecke’s feeling very sheepish, and Lina crying miserably, and only Rudolf, who’s just a stubborn, loud-mouthed urchin and always against the military – only Rudolf had a pig-headed look on his face as if to say: what a stupid fuss, I could have rowed you out of it too.’

‘Yes, that’s what he is, a loud-mouthed urchin; I know him. But what about the two gen’l’men? That’s the important thing.’

22 ‘Well, first they made sure we were all right, and then they sat down at the table next to ours and kept looking over at us. And at about seven, when it was starting to get dark and we were getting ready to go home, one of them came up to ask if we would allow him and his friend to escort us. In my high spirits I laughed and said that they’d rescued us and a rescuer mustn’t be denied anything, but they might want to reconsider because we lived more or less at the other end of the world, so getting there was quite a trek. To which he obligingly said “All the better.” By then the other one had come over … Oh, Frau Dörr, it might not have been the right thing to do, speaking straight off in such a free way, but I’d taken a liking to one of them, and putting on airs and acting coy is something I’ve never been able to do. And so we walked the whole way, first along the Spree and then by the canal.’

‘And Rudolf?’

‘He walked behind, as if he didn’t know us, but he made sure he saw everything that was going on. Which was only right, with Lina being only eighteen and still a good, innocent girl.’

‘Do you think so?’

‘I’m sure, Frau Dörr. You only have to look at her. You can see that sort of thing at a glance.’

‘Yes, mostly. But not always. And so they brought you back home, then?’

‘Yes, Frau Dörr.’

‘And then what?’

‘Then … Well, you know what happened. He came the next day to ask after me. And since then he’s often come, and I’m always glad when he does. Lord, it’s a pleasure just to have something going on. It’s often so lonely out here. And as you know, Frau Dörr, mother’s got nothing against it and she always says, “There’s no harm in it, my child. Before you know it old age has crept up on you.”’

23 ‘Yes, yes,’ said Frau Dörr, ‘I’ve heard Frau Nimptsch sayin’ things like that too. And she’s quite right. At least, it depends how you look at it, an’ livin’ by the catechism’s always better, an’ you could say best of all. You can believe me there. But I well know that it’s not always possible, and some folk jus’ don’t want to. An’ if they don’t want to, well, there’s no forcin’ them. They have to find their own way, and mostly they do, providin’ they’re honest an’ decent an’ stick to their word. An’ of course, whatever happens you’ve got to put up with it – can’t go complainin’. An’ if you realize all that and keep remindin’ yourself of it, well, you can’t go far wrong. The only thing wrong is if you start gettin’ ideas.’

‘Oh, my dear Frau Dörr,’ Lene said laughingly, ‘what are you thinking of? Ideas indeed! I’m not getting any ideas. If I love someone then I love him. That’s enough for me, and I want nothing else from him at all, nothing, nothing at all. Just my heart beating faster and counting the hours till he comes and then not being able to wait till he’s here again – that’s what makes me happy, that’s enough for me.’

‘Yes,’ said Frau Dörr with a quiet smile, ‘that’s the way, that’s how it should be. But is it really true he’s called Botho?† Surely no one can have a name like that. I mean, it’s not Christian.’

‘Yes they can, Frau Dörr.’ And Lene was preparing to confirm the existence of such names when Sultan began to bark, and at the same instant they clearly heard someone stepping into the hallway. Sure enough, the postman appeared and brought two orders for Dörr and a letter for Lene.

‘Lord, Hahnke,’ cried Frau Dörr to the man covered in great beads of sweat before her, ‘it’s drippin’ off you. Is it really that hot? An’ only half past nine. I can see it’s not much fun being a postman.’

24 And the good woman made to go and fetch a glass of fresh milk, but Hahnke declined. ‘Can’t stop now, Frau Dörr. Another time.’ And with that he left.

Meanwhile Lene had unsealed her letter.

‘Well, what does he say?’

‘He’s not coming today, but he will tomorrow. Oh, it’s so long till tomorrow. Good thing I’ve got work to do; the more work the better. And this afternoon I’ll come over to your garden and help with the digging – but Dörr mustn’t be there.’

‘God forbid.’

And then they separated, and Lene went into the front room to take her old mother the portion of asparagus that Frau Dörr had given her.

* Famous Berlin square commonly used for markets. Its name derives from the Gensdarmes cavalry regiment which deployed there in the previous century.

† A pagan Germanic name (pronounced Bawtaw) of the sort that gained renewed currency in the wake of the Romantic movement.

4

It was now the following evening and Baron Botho due to arrive. Lene paced up and down the front garden, while indoors Frau Nimptsch sat as usual in the big front room before the hearth, around which, as so often, the full complement of the Dörr family was also assembled. With big wooden needles Frau Dörr was knitting her husband a blue woollen cardigan, which, shapeless as yet, lay like a large fleece on her lap. Beside her was Dörr, his legs comfortably crossed, smoking a clay pipe, while his son sat in a big grandfather chair close by the window and leant his ginger-topped head against its wing; he was out of bed every morning at cockcrow, and would often, as now, be overcome by sleep in the evening. Nobody said much, and all that could be heard was the clicking of the wooden needles and the nibbling of the squirrel which came out of its little sentry-box from time to time and peered curiously around. The only light came from the fire in the hearth and the glow of the setting sun.

From where she sat Frau Dörr could see right up the narrow garden path and, even in the twilight, make out anyone walking along the border hedge towards them.

‘Ah, here he comes,’ she said. ‘Now Dörr, put that pipe out. You’ve been like a chimney again today, puffin’ an’ smokin’ from mornin’ till night. And the smell it belches out isn’t to everyone’s taste.’

Dörr paid little heed to these observations, and before his wife could enlarge on them or say anything else the baron walked in. He was visibly on the merry side, having come straight from imbibing a May punch, the object of a wager at his club, and he held out his hand to Frau Nimptsch and said, ‘Good day to you, mother. Keeping well, I trust. And Frau Dörr as well, and Herr Dörr, my 26 old friend and benefactor. I say, Dörr, what do you think of the weather? Just the thing for you, and for me too. My meadows at home, which are under water four years in five and produce nothing but buttercups – they can do with weather like this. It’ll do Lene good too, get her out of the house more; she’s been getting a trifle pale for my liking.’

As he spoke Lene placed a wooden chair next to the old woman, knowing that this was where Baron Botho best liked to sit; but by this time Frau Dörr, who was strongly of the view that a baron must sit in the place of honour, had stood up and, trailing her blue fleece behind her, shouted to her stepson, ‘Come on, get up! Honestly! But what do you expect when he’s got nothin’ between his ears?’ Still befuddled by sleep, the poor boy shot to his feet and made to give up his seat, but the baron would not hear of it: ‘For heaven’s sake, my dear Frau Dörr, let the boy alone. I’d far rather sit on a stool like my friend Dörr here.’

And with that he pushed the wooden chair that Lene was still holding ready next to the old woman, and as he sat down he said, ‘Here next to Frau Nimptsch, that’s the best place. I can think of no other hearth I’d rather gaze at. Always a fire in it and plenty of warmth. Yes, mother, it’s the truth: this is the best place of all.’

‘Well, goodness me,’ said the old woman. ‘This the best place, at an old ironing-and-washerwoman’s house!’

‘Of course. And why not? Each station in life has its dignity, including a washerwoman’s. Did you know, mother, that a famous poet once lived here in Berlin who wrote a poem about his old washerwoman?’*

‘It’s not possible.’

27 ‘Of course it’s possible. In fact it’s certain. And do you know what he said at the end of it? He said he’d like to live and die like the old washerwoman. Yes, that’s what he said.’