6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

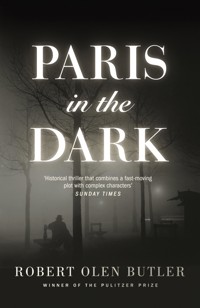

Nominated for the 2019 Hammett Prize Autumn 1915. The First World War is raging across Europe. Woodrow Wilson has kept Americans out of the trenches, although that hasn't stopped young men and women from crossing the Atlantic to volunteer at the front. Christopher Marlowe 'Kit' Cobb, a Chicago reporter and undercover agent for the US government is in Paris when he meets an enigmatic nurse called Louise. Officially in the city for a story about American ambulance drivers, Cobb is grateful for the opportunity to get to know her but soon his intelligence handler, James Polk Trask, extends his mission. Parisians are meeting 'death by dynamite' in a new campaign of bombings, and the German-speaking Kit seems just the man to discover who is behind this - possibly a German operative who has infiltrated with the waves of refugees? And so begins a pursuit that will test Kit Cobb, in all his roles, to the very limits of his principles, wits and talents for survival. Fleetly plotted and engaging with political and cultural issues that resonate deeply today, Paris in the Dark is a page-turning novel of unmistakable literary quality.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

PARIS IN THE DARK

Paris in the Dark, Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Olen Butler’s return to his lauded Christopher Marlowe Cobb series, is a page-turning novel of unmistakable literary quality.

Autumn 1915. The First World War is raging across Europe. Woodrow Wilson has kept Americans out of the trenches, although that hasn’t stopped young men and women from crossing the Atlantic to volunteer at the front. Christopher Marlowe ‘Kit’ Cobb, a Chicago reporter and undercover agent for the US government is in Paris when he meets an enigmatic nurse called Louise. Officially in the city for a story about American ambulance drivers, Cobb is grateful for the opportunity to get to know her but soon his intelligence handler, James Polk Trask, extends his mission. Parisians are meeting ‘death by dynamite’ in a new campaign of bombings, and the German-speaking Kit seems just the man to discover who is behind this – possibly a German operative who has infiltrated with the waves of refugees? And so begins a pursuit that will test Kit Cobb, in all his roles, to the very limits of his principles, wits and talents for survival.

Fleetly plotted and engaging with political and cultural issues that resonate deeply today, Paris in the Dark is the finest novel yet in this riveting series.

About the author

Photo by WFSU Public Media

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER is one of the most prolific of America's most highly regarded writers, having published 17 novels, 6 short story collections, and a book on the creative process. Among his numerous awards is the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Four of his novels are historical espionage thrillers in the Christopher Marlowe Cobb series. He is also a widely admired and sought-after university teacher of creative writing, who counts among his former students another Pulitzer Prize winner.

PRAISE FORTHE EMPIRE OF NIGHT

‘Mr Butler does a terrific job of depicting both the journalist’s facility for teasing information from his subjects and the spy’s incessant fear of being discovered. There’s something almost magical about the way the author re-creates this 1915 milieu…’ –The Wall Street Journal

PRAISE FOR THE STAR OF ISTANBUL

‘Zestful, thrilling… a ripping good yarn’ – Wall Street Journal

‘An outstanding work of historical fiction’ – Huntington News

‘The Star of Istanbul has it all: history galore, exotic foreign settings, a world-weary yet engaging protagonist, villains in abundance and a romance worthy of Bogart and Bergman’ – BookPage

‘Double and triple crosses merge like lanes in a traffic roundabout, and… the novel commingles character-driven historical fiction with melodrama and swashbuckling action. Somehow… it all works; on one level, Butler is playing with genre conventions in an almost mad-scientist manner, but at the same time, he holds the reader transfixed, like a kid at a Saturday matinee’ – Booklist (starred review)

‘Butler impresses with his exceptional attention to historical detail, particularly aboard the Lusitania’ – Publishers Weekly

‘Butler is an excellent observer of interior psychological detail… and his fine description of the Lusitania’s demise shows he can write action-packed scenes as well… It’s a pleasure to watch Cobb clear away layer upon layer of scheming and disguises to expose some ugly truths about humanity’ – Kirkus Reviews

‘While The Star of Istanbul meets the genre requirements for action and plotting, the precision and lyricism of Butler’s language, his incisive observations, his psychologically complex characters, and his understanding of the past lift this novel well into a genre of its own’ – Arts Fuse

‘Butler’s grasp of history is excellent… You will enjoy every new twist and turn in this spy game’ – Arab Voice

‘[Butler’s] description of the aftermath of the attack on the Lusitania will leave you with your heart in your mouth… Yet another remarkable work from an author who continues, at this advanced stage of his career, to surpass himself’ – Bookreporter

‘Butler’s description of the sinking of the Lusitania is exceptional… In Cobb, Butler has created an appealing hero’ – Readers Unbound

‘An exciting thriller with plenty of action, romance, and danger… Fans of historical spy fiction will enjoy this fast-paced journey through a world at war’ – Library Journal

PRAISE FOR THE HOT COUNTRY

‘The Hot Country draws on many elements of the traditional adventure yarn, including disguises, fist fights and foot races, double agents and alluring young women who may be honey traps or spies… though in prose that has been written with serious attention… this first report makes you want to read on into the war correspondent’s second edition’ – Guardian

‘combines a fast-moving plot with characters of a complexity that is not always found in such fiction’ – Sunday Times

‘a genuine and exhilarating success’ – Times Literary Supplement

‘a historical thriller of admirable depth and intelligence’ – BBC History Magazine

‘Exciting story…The Hot Countryis a thinking person’s historical thriller, the kind of exotic adventure that, in better days, would have been filmed by Sam Peckinpah’–Washington Post

‘high-spirited adventure… great writing’–New York Times

‘Literate, funny, action-packed, vivid, and intriguing’–Historical Novel Society

‘A fine stylist, Butler renders the time and place in perfect detail’ –Publishers Weekly

‘Butler writes thrilling battle scenes, cracking dialogue and evocative description, and the plot ofThe Hot Countrykeeps twisting to the very end’ –Tampa Bay Times

Also by Robert Olen Butler

The Alleys of Eden

Sun Dogs

Countrymen of Bones

On Distant Ground

Wabash

The Deuce

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain

They Whisper

Tabloid Dreams

The Deep Green Sea

Mr Spaceman

Fair Warning

Had a Good Time

From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction

(Janet Burroway, Editor)

Severance

Intercourse

Hell

Weegee Stories

A Small Hotel

The Hot Country

The Star of Istanbul

The Empire of Night

Perfume River

For Kelly

1

In the dark above Paris, in the deep autumn of 1915, there were always the Nieuports flying their patterns, like sentries walking a perimeter. The new, svelte Model 11 – called Bébé by its pilots – operated above the high-flying Zeppelins, poised to drop on them in a column of searchlight if the Zepps got by the guns at the French forts to the east.

On a November night I sat beneath the Nieuports at a table outside the Café de la Rotonde. The weather had been unpredictable. It snowed last week but tonight it was almost mild. It might as well have been April and that hammering of engine pistons up above might as was well have been French worker bees going after chestnut blossoms.

My drink was a Bijou – the greenery taste of the chartreuse fitting right in with the bees in the night – and I was surrounded by people I couldn’t actually see, just vague shapes and spots of cigarette flame. But I knew who they were, the assorted male denizens of the Left Bank. Artists and professors; students furloughed for six days from Hell; students furloughed for good by a stump of an arm or an empty pants leg; the old, the infirm, the foreigners.

The conversations – at turns hopeful, fearful, or miffed – had been low, as if the Zepps would hear us, and I’d sat away from them, near the street. I had my own brooding and ranting to do, which I kept to myself.

But now a voice rang clearly in the dark.

‘Monsieur. You will like one Bijou more?’

I looked up at the shadow hovering above me. He’d spoken in English but wallowing the words in his mouth as the French do. He was old enough to have grandsons in the trenches.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘That is just what I need.’

I’d replied in French. My French was pretty good. My actress mother, who took on my education in all subjects, knew French well from playing Racine and Corneille in her two long, triumphant tours of the Continent in the mid-Nineties. And from a beau or two of hers along the way.

Before the waiter moved off, I said, ‘Henri, isn’t it?’

‘Yes that is me,’ he said. ‘Have I forgotten you, to my shame?’ He was speaking French to me now.

‘Ah no,’ I said. ‘I heard someone address you.’

‘Thank you,’ he said.

I said, ‘I always like to know the name of the man who will help me become more or less drunk.’

Henri laughed a faintly suppressed laugh.

‘I’m Kit Cobb,’ I said.

‘Monsieur Cobb. You are American, yes?’

‘Yes I am.’

‘You are here.’ He paused. I grew up in the theater. I knew how to hear subtext. Here meaning Paris. Meaning Paris deep into the Great War. His silence said: Though your countrymen are not. Then he finished formally, courteously. ‘I am grateful to you.’

‘Plenty of us will be here,’ I said, addressing the thing he’d left unsaid. ‘To fight. The day is coming.’

He lowered his voice. ‘There are too many professors.’

I shot him a smile, though I doubted he could see it. He knew his clientele here amidst the universities of Paris on the Left Bank. And he knew our American president.

‘I share your distaste,’ I said. Then, so he knew I knew what he was really saying, I added, ‘For Professor Wilson.’

He chuckled, and I could even make out his shrug. ‘But still your countrymen will come?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘I pray it will be in time.’

‘So do I.’

‘And you, sir? What do you do in Paris?’

Ah, how to answer that.

I was a reporter. A war correspondent. But hobbled, thanks to Henri’s government. And part-time, thanks to mine. I was also a spy.

But I said something that surprised Henri, and surprised me too: Je suis poilu. I did not know how to explain other than to lift my arm and tap myself on the heart. I hoped he could see the gesture. I am a poilu.

The public – everyone in France – called the French infantryman le poilu. The hairy man. As a reporter of wars, I’d known a great many hairy men under various flags in my life.

He did see the gesture. Or he already understood. ‘We must all be poilu,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said. Emphatically. Bien oui. ‘Your boys will hold on. I am sure of this.’

‘Vive la France,’ Henri said, almost in a whisper.

I said it too, and as I did, I realized that he’d whispered so his voice would not crack from emotion.

He was gone.

Three or four searchlights flared up now and scraped around against the ceiling of clouds, and then abruptly, quietly vanished again.

I knew the sound of Zepps and there was none of that. Only the buzz of the Nieuports.

I drained what was left of my present Bijou and it burned its way up into my nose and all through my head.

There’d be no Zeppelins tonight. The German command had lately shifted their attention to the more vulnerable London. I knew something about all that, had even exerted a bit of influence on those operations during a challenging week at the end of August, when I’d no longer been Kit Cobb at all but a man who existed only in phony documents and a scrim of lies, sneaking around Germany for my country’s secret service.

I’d done well enough that I’d been able to insist on a couple of month’s break from being a spy so I could be who I really was.

As if that were actually possible in this wretched war.

My own quiet café rant, as a war correspondent, had to do with one of the nasty advances of this so-called Great War. Strictly codified censorship of the news. A parallel war against a free press. We could not get into the battle-line trenches where the bodies of the husbands and sons and fathers of Europe were being savaged, countless tens of thousands of them, just forty miles from where I sat. We could not even follow the battlefield advances and retreats until the events were reviewed and adulterated by the generals and the politicians. All in the name of public morale.

At least I’d gotten clearance from the French War Office of Muckety-Muck Press-Suppression to write what might become a decent story. Might even get me close to the action. A feature on the American volunteers driving ambulances to and from the Western Front. The French approved, I figured, because it might give Woody Wilson a kick in the butt, a big story in the U.S. papers about all these American college boys and farm boys and mailmen and store clerks finding the guts that the American president can’t find, to come to France and stand up to Kaiser Willie.

Henri returned with my third Bijou, my intended last, for I would be working tomorrow.

He set it in front of me and said, ‘Perhaps soon the British will be of more help.’

I thought I heard his subtext: Since America won’t likely be. But as clear-headed as Henri could be about us, he was buying the propaganda about the Brits. He immediately said, ‘Perhaps from the meeting something good will come.’

Adjoining the war ministry’s office for the suppression of news was the office for manipulating the news. These mugs were doing a lapel-grabbing sales-job about a meeting in Paris in a week and a half. General Joseph Joffre and General Archibald Murray, the chiefs of their respective general staffs, were coming to a local hotel. Old Archie, as he was called, was the third such chief since the beginning of the war and the Brits still hadn’t gotten their act together. Short on artillery shells. Short on men. Doing little enough in the war to worry the hell out of the French.

But Henri was hopeful. The power of the press, even if it was in the back pocket of a government.

‘Let’s hope,’ I said to him.

I figured Henri had his unspoken doubts, however, as he had no further hopeful word to add beyond, ‘Enjoy your drink, Monsieur Cobb.’

He slipped away.

I looked into the dim expanse of the Boulevard du Montparnasse.

I sipped my Bijou.

Five streets converge around La Rotonde and two of them were over my left shoulder. I did not have to turn to recognize the sound that was swelling along one of them. I heard it in this quarter of the city often. The iron-rimmed wheels of a fiacre and the iron-shod hooves of its horse, hurrying this way with a fare, the sound of metal on cobble drumming up another sound beneath it, from deeply beneath, a cavernous sound found in no other city in the world. This whole area sat upon the Catacombs, the ancient limestone quarries that now held the skeletons of six million dead, the cemeteries of Paris disgorged more than a century ago.

The carriage rushed past. Dim as a ghost, I thought. Or: As if chased by the ghosts it was summoning up. I itched to type my byline and plow into a story on the Corona Portable Number 3 that waited for me on my desk in the small hotel up the Rue de Seine.

Soon there would be some Americans to talk to. At least that. From the American Ambulance Hospital of Paris, in the city’s adjacent commune of Neuilly-sur-Seine. A hospital full of volunteers. I turned my thoughts to them. Nurses in white caps. Guys in khakis. Americans.

And from off to the west the air cracked. The sound brass-knuckled us and faded away.

A bomb. Awful big or very near.

All around me the shadows of men had risen up and were retreating into the bar. They had the Zepps in mind. I jumped up too but stepped out onto the pavement of Boulevard Montparnasse. The fiacre had stopped cold and the horse was rearing and whinnying.

It wasn’t Zepps. I’d have heard their engines. And the crack and fade were distinctive. Dynamite. This was a hand-delivered explosive. I looked west. Five hundred yards along the boulevard I could make out a billow of smoke glowing piss-yellow in the dark.

I made off in that direction at a swift jog.

My footfalls rang loud. Nothing was moving around me in the dark. Or ahead in the glow. I pressed on, and ahead I recognized another convergence of streets, the Place des Rennes, before the quarter’s big railroad station, the Gare Montparnasse.

As I neared, there were sounds. Battlefield sounds just after an engagement. The silence of ceased weapon fire filled with the afterclap of moaning, of gasping babble. Nearer still I heard the approaching fire-engine hooters and police whistles, and I saw figures dashing across the boulevard from the station.

I entered the Place des Rennes.

There were lights now. Gas lamps from the broad, two-storied front facade of the train station; tungsten beams of gendarme flashlights; incidental fires in the wreckage.

Someone had bombed the ground floor café in the Terminus Montparnasse Hôtel, reduced it to the twisted ironwork of the sidewalk canopy, the shredded and smoldering canvas of the awning, the fragmented clutter of what had been tables and chairs.

I stepped onto a trolley island halfway across the place.

A long-hooded Renault ambulance brisked by in front of me and turned sharply right, stopping in front of the hotel.

The police were wading into the bomb site now, abruptly bending forward, crouching low. To bodies I could not see.

I took a step off the island and onto the cobbles. My foot nudged something and I stopped again. I looked down.

A man’s naked arm, severed at the elbow, its hand with palm turned upward, its fingers splayed in the direction of the café, as if it were the master of ceremonies to this production of the Grand Guignol. Mesdames et messieurs, je vous présente la Grande Guerre. The goddamn Great War.

I lifted my eyes once more to the Café Terminus.

Not one detail I was witnessing – not a bistro table in the middle of Boulevard Montparnasse, not the severed arm at my feet – would ever make it past the news censor’s knife.

As for me, I’d seen enough for tonight.

I turned.

I walked away.

And I realized I’d left something undone.

I walked quickly on.

At La Rotonde, some of my previous drinking companions had re-emerged, mostly the wounded and the furloughed. A couple of the soldiers who were still whole were on the sidewalk looking in the direction from which I came. All the rest had resumed their seats.

I turned in and entered the café. The civilians – the professors and the elderly and the routinely infirm – were holding on, but they were inside now, at the marble-topped tables.

I stopped and looked to do what I needed to do.

Henri was turning away from the bar. He saw me and crossed to me.

I pulled money from my pocket.

He nodded to me gravely.

‘I hope you didn’t think I was running from my bill,’ I said in French.

‘Of course not,’ he said. ‘Did you see?’

‘A bomb at the Terminus Hôtel.’

Henri cursed. Low. ‘The Barbarians,’ he said. Meaning the Germans. ‘They are among us.’

2

The next morning I was in a horse-drawn fiacre, its iron wheel-rims ringing on the cobblestones, its four-seat cabin smelling of chilled mildew, its leather seats brittle from age, a vehicle of the sort resuscitated into Paris use to replace the motorized taxis, most of which – along with every last motorbus – were now off plying the roads to the front for the French army.

We crossed the Seine at Pont Royal and skirted the Tuileries. The figures moving among the garden’s chestnut trees were mostly men on crutches and women in black. I wondered if they went there with the intention to meet, these two constituencies of a grim wartime social club, to find consolation in each other. Beyond the gardens we headed west on the Champs Élysées at a surprising trot for a bay horse starting to dip in the back and go bony in the withers. The old boy was another resuscitation project, a good French horse relinquishing retirement, pitching in. Soon he carried us out of Paris at the Porte Maillot and into Neuilly.

All this way, I noted the passing scene only idly, the journalist in me collecting details to describe the city for my readers in Chicago. My mind was out ahead of my resolute old horse, devising questions for the superintendent of the American Hospital, the American nurses in the ward, the French soldiers in the beds, and, of course, the boys who might get me near the action, the American ambulance drivers, though my initial time with them wouldn’t be till tomorrow, at day’s end, at the New York Bar on the Right Bank.

I noted our turn north. I moved my eyes to the window of the fiacre. We negotiated our way through a large intersection and, shortly thereafter, a smaller one. The hospital wasn’t far now. Then we passed a line of road-roughed recent refugees that stretched across the front of a homely, Gothic-revival Protestant church, through the church yard, and into a heavy canvas shelter tent next door.

Henri bent near in my head and repeated himself. The Barbarians. They are among us.

And the thought occurred to me: This is how.

Unarmed, bedraggled, seeming to flee the carnage, anyone could enter the city and vanish and then reappear in the dark with a bomb, the Nieuports above powerless.

And then there were the others who were coming to Paris from the carnage. An hour later I stood before such a man. Only his eyes were visible. A poilu. The rest of his face was hidden beneath bandages. What face there might have been.

He lay in one of the dozens of nine-bed wards at the American Hospital, in a space built as a classroom. To the ‘American Warriors of Mercy’ – I was phrase-making already in my head for my readers in Chicago and across the country on the newswires – to these volunteer Americans, the French government had turned over a newly finished but still unoccupied school building, the Lycée Pasteur. A massive four-story French Renaissance quadrangle of red brick and white stone facings built around a courtyard. The doctors and presiding ward-nurses were from American university medical schools. The nurse ‘auxiliaries’ were young women with guts and independence and, among the ones who stuck it out, strong stomachs for hospital dirty work. Assorted women. They were actresses and typists and shop girls, tenement girls and society girls. One was even Secretary of the Treasury McAdoo’s daughter.

At my side was a Harvard doctor, talking with a tinge of compulsion about head and face and foot wounds from the trenches. About compound fractures from collapsing buildings. And about the shrapnel wounds. On these he paused, as if searching for a word, and then said, ‘These are hard to describe, in their terrible variety.’

I turned to the wrapped face before us. The eyes were shut.

‘The random tumble of metal through torsos,’ the doctor said. ‘Parts of faces blown away.’

The eyes opened and moved to the doctor.

The doctor did not notice. His tone wasn’t clinical. But neither was it empathetic. Perhaps it was ironic. He was middle-aged and until a few months ago had been a university teaching-doctor for American Brahmans. The shrapnel tumbled through him, as well, a hundred times a day, with the savage irony of his dealing with these shards of war in a school building. His detached tone was a wrap of bandages around him.

I returned to the poilu and he’d shut his eyes again. Had he understood the English?

‘Ah, Louise,’ the doctor said.

I looked toward the door.

She was all in white linen. Her nurse’s cap had a black stripe across it, near the crown. She was pale as her linen but her eyes were gray as shrapnel and they were sorrowful as a pup’s. The cap stripe signified a senior rank, though she was young, this Louise.

‘Nurse,’ the doctor said to her, with a corrective stress on the word as if his use of her name had been a breach of protocol.

She arrived.

She nodded at the doctor.

On this morning, she still smelled of lilac water, not yet of wound-drain and carbolic acid. Touching, really, given the professionally hardened look in her lovely large eyes, given her senior status in a tough trade, touching to me that she would splash this parlor-and-parasol smell onto her body before a day of wounds and death.

She nodded at me. And she let her gaze fix unwaveringly on mine as the doctor spoke my name, fully, Christopher Marlowe Cobb, and hers, Supervising Nurse Louise Pickering.

I offered my hand.

She took it with a man’s grip. A smallish, bookish man perhaps, but a meet-you-more-than-halfway man. I’d known a few suffragettes pretty well and was increasingly fine with that.

She seemed willing to shake a moment or two more, but I let go.

‘The American newsman I spoke of,’ the doctor said to her.

‘I assumed,’ she said, directly to him, and then she turned and assessed me for a few moments as if I’d just been carried in from the back of an ambulance.

The doctor excused himself. ‘I leave you in the capable hands of Nurse Pickering,’ he said.

We watched him go.

I said, ‘So he’s a Harvard man, the doctor.’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘And you?’

‘I’m not a Harvard man.’ She said this with no smile, no twinkle. She was either drily witty or contemptuous of newsmen. Or a natural copy editor. I’d spoken ambiguously, after all, though I’d tried for drily witty.

So just as smileless and twinkleless, I asked, ‘A Radcliffe man?’

She paused for a breath or two. I held mine, in sudden regret for proceeding on the assumption she’d been bantering. I didn’t need to banter with her, even if she had wonderful eyes and smelled of lilacs. I had a story to write. I was more interested in the drivers, but she was important for background on this whole operation.

‘Not Radcliffe either,’ she said. ‘My liberal arts were bedpans and sponge baths. Which I studied at Massachusetts General.’

‘You’ve come far,’ I said, tentatively relieved.

‘I have,’ she said, and whatever playful thing it was that seemed to have begun between us seemed now to have ended.

And so we had some time together, Nurse Louise and I, and it was all business between the two of us. But inside the wards I encountered the wreckage of men like men I’d encountered before, in Nicaragua and Bulgaria, in Mexico and Turkey. Most of the others I’d been with were in their nakedly wounded state, at the site of the clash of arms. Here the men were washed and drained and reassembled and swathed. Here they were – to a man, among the ones capable of talking to me – calm and bucked up and cheerfully brave in their sunlit rooms. With these who were aware, I made sure to leave each of them with a firm touch. A hand taken up to shake, a shoulder squeezed, from one man who knew war to another.

Between the wards, as we moved along the hardwood hallways of this intended school, Nurse Louise spoke to me of the hospital’s various new machines, made for X-rays and ultra-violet sterilizing and magnetic removal of shell fragments from wounds. She spoke of four hundred beds soon to become six hundred. She spoke of sepsis and gangrene and tetanus, how infection was the nearly universal state of these men’s wounds when they first emerged from the ambulances, spoke of how it was dealt with.

And as she spoke through the tour, she rarely looked me in the eyes, in spite of the close scrutiny she’d given me when we first met. Or maybe because of that scrutiny. Perhaps she’d seen all she cared to see. She spoke to me coolly, clinically, even as she offered her own warm asides – toasty greetings and pillow-fluffings and shoulder-pattings – to the men in the beds.

We ended in the administrative wing, where she stopped me several paces short of the hospital superintendent’s office. Her back was to a high, bright, mullioned window.

I’d been taking notes all this time. Mostly out of courtesy, because for the story I had in mind, the real stuff was still to come. I put my notebook in my pocket. I offered my hand.

She began to shake it again.

Softer this time, it seemed to me. I softened too. Now she was looking at me again, the gray eyes gone nearly black with the backdrop of daylight.

‘Thank you, Supervising Nurse Pickering,’ I said.

She pinched her mouth to the side. I’d certainly intended to needle her just a little with the formality, but I didn’t expect her to do a mouth-pinch.

Whatever that might mean.

But it seemed to me that it meant something.

She kept shaking my hand softly for a moment more and said, ‘Good luck, Mr Cobb.’

‘Kit,’ I said.

‘Ah,’ she said. ‘As your namesake.’

‘Christopher Marlowe. Yes.’

She let go of my hand.

Now that things had softened between us a little, I didn’t want to let go quite yet. I sought more talk, but not clinical, not chilly. She knew her Elizabethan playwrights. I asked, ‘Were you a theatergoer in Boston?’

‘When I could occasionally afford a narrow place in an upper balcony.’

‘Did you ever see Isabel Cobb?’ I didn’t make a practice of invoking my mother in order to small-talk a beautiful woman. But Mother had a salutary effect on certain kinds of beautiful young women. Ones, particularly, who had inner resources enough to shake a man’s hand as an equal and seek out a war.

Louise briefly cocked her head at me, with narrowed eyes. It was a how-did-you-know look. She said, ‘As a child I saw her every day.’

It was my turn to cock my head. As in: Are you pulling my leg?

She smiled faintly, the first smile she’d shown since I met her. She said, ‘My father smoked Duke’s Honest Long Cut. He had lithograph cards of Isabel Cobb and Lillian Russell on our mantelpiece for years. His two favorites.’

‘I know her Duke’s card,’ I said. ‘Is she wearing a Welsh-crown hat covered in bird plumes?’

‘Yes. Her eyes are raised. I thought, when I was a child, that her look was sympathetic. Rather regretful. As if she were watching the flight of the plucked bird.’

I hemmed at this. I did not want to point out how unlike my mother that would be. Isabel Cobb may never in her life have sympathetically noticed a bird, plucked or unplucked. In the look on her face that was stuffed into all those tins of tobacco, there was only a keen consciousness of her own beauty. She kept that same tobacco card on her dressing table for years afterwards, even when her fame far exceeded early-career recognition by Duke’s of Durham.

I said, ‘So did you ever see Isabel Cobb in person?’ I stressed the surname ever so lightly for her.

I watched her suddenly fit two things together. She cocked her head again. ‘Cobb,’ she said. ‘Is she related to you?’

‘She’s my mother.’

At last the composure of Supervising Nurse Louise faltered a little. She was impressed.

She actually sighed. ‘I saw her once. We lived in Gloucester till I went off to become a nurse. During my time in Boston I never had a chance. But my father brought me down to the city once for your mother. When I was sixteen. She played Medea.’

‘She was a good Medea.’

‘Very good.’

We fell silent, Louise Pickering and I. Not knowing what to say next. Mama had taken over the stage, as she was wont to do. Though, to be fair, it was I who’d spoken her entry line.

But before I could figure out how to induce my mother to exit stage left, Louise said, ‘I have to go, Mr Cobb. Superintendent Pichon is expecting you.’

‘Thank you for your help, Nurse Pickering.’

I expected her to turn away, but she hesitated a moment more. I watched her eyes upon me, which were intent, as if making a parting assessment. Then she said, ‘You seemed genuinely to care about them.’

I didn’t understand.

‘The wounded,’ she said.

She’d noticed that in the wards. Now she’d skipped over the mother-banter to go back to it. I liked this Louise Pickering.

‘I’ve seen a lot of them,’ I said.

‘So have I,’ she said, very softly, as if it were a secret between us.

And with this, she turned and walked briskly away.

3

At nine o’clock the next morning I stepped out of my hotel on the Rue de Seine to find a massive American automobile sitting at the curb. Even as a beautiful woman passing by might have riveted my attention while a rogue chimney pot plummeted toward my head, I stopped to ogle a maroon-bodied, black-roofed, closed-cabin Model 48 Pierce-Arrow, its famous fender-molded headlights bug-eyeing the street ahead, making this two-ton beauty seem always yearning to rev up and dash off.

Then the chimney pot.

A familiar voice. It said, ‘Kit Cobb.’

A familiar face. This was framed in the open rear window of the Pierce-Arrow’s passenger vestibule, with a clean-shaven and pugilist-square chin, brilliantined black hair, dark eyes as unwavering as a sharpshooter’s.

James Polk Trask had come for me.

Not me. Not the me I came to Paris to be. Came, no doubt, for the agent of his secret service.

I hesitated.

He waited.

Trask’s driver, with a muscleman body straining at his serge suit, popped out of the driver’s compartment and opened the vestibule door.

I stepped in and sat beside Trask, who said to his man, ‘Drive along the river.’

The door thumped shut.

‘Nice automobile,’ I said.

‘The Ambassador’s,’ he said, and he turned his face to the window beside him.

I figured he knew what I was going to say next. Which I said: ‘But I was supposed to be the one to get in touch. When I was ready.’

He was looking at my modest, newswriter-cozy hotel. He craned his neck to take in its upper floors and said, ‘We could have done better for you.’

As if I’d have gone straight back to spy work for the sake of a better hotel room; as if he’d even have sent me to Paris at all instead of Sofia or Baghdad or Pinsk. This declaration came from what I had come to understand as J.P. Trask in a playful mood. His own special brand of playful. Say a pointed thing without a direct transition from what preceded it. Couch it in the commonplace. Let you fill in the skipped steps buried in the subtext.

I played it back to him: ‘Were you waiting long?’

We pulled away from the curb and he returned his face to me. When we first started working together – what seemed like a long, long time ago but, in fact, was less than two years – he would have continued to show me nothing in his demeanor, even as I joined him in his game. Now he gave me a fleeting smile, the eyes never wavering. ‘You keep regular hours.’

He’d been watching me. Of course he had.

After a brief beat of silence he added, ‘How’s the story going?’

‘At its own necessary pace,’ I said.

The driver braked and used the Klaxon on something in our way. Neither Trask nor I looked to see what.

The game now was not to flinch first.

As if that would decide whether I did my story or worked for him.

Neither of us was giving in.

We were accelerating again, though we were still in the tight confines of the Rue de Seine.

‘How are things in Washington?’ I said. Back there, Trask had but to lean a little to speak directly into Woodrow Wilson’s ear. Though that privilege was still doing less good than Trask wished. He and I had the same assessment of Woody’s backbone. But at least the president was giving his secret service a more or less free hand to stay involved over here. As long as we did our work quietly.

Trask replied, ‘One year from tomorrow, fifteen million men will elect two hundred and eighteen representatives, thirty-five senators, and one president of the United States.’

‘So things are jumpy,’ I said.

‘Darwinian,’ he said.

‘Can he be beat?’

‘If France and England were voting, no doubt.’

‘As for our fellas?’

‘I don’t know. So far the Republican contenders are just a bunch of favorite sons. But then there’s Teddy.’

‘As a Bull Moose?’

‘His third party only succeeded in giving us Wilson last time. He knows that. There’s talk he’ll come back to the Republicans.’

‘We’d be rough-riding into France the day after his inauguration,’ I said.

‘That’s sixteen months away.’ He said it almost off-hand. Willfully so. A Traskian show of emotion.

We both fell silent.

I could hear him thinking: So in the meantime we’ve got our work cut out for us.

I doubt if he heard me thinking: Not till I finish my story.