1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: via tolino media

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

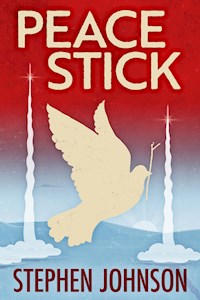

Peace Stick is set in East Germany during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. It's a story about hope and innocence during a nuclear showdown between the superpowers. It was inspired by an Erfurt schoolgirl who wanted to survive the confrontation to finish her studies, start a career, raise a family and enjoy a life that was being threatened by angry old men. She created a peace stick as a lucky charm. It was hidden in a school wall to be a symbol of hope during a traumatic week. Peace Stick is a snapshot of life behind the Iron Curtain as the world teetered on the edge of a nuclear abyss. It is representative of many kinder throughout the world who were endangered by political folly. It's a story that resonates to the present day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

PEACE STICK

Stephen Johnson

Published by Stephen Johnson in 2022

Copyright © Stephen Johnson

This is a fictional story about an historic event.

All rights reserved. No Part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including internet search engines and retailers, electronic or mechanical, photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-473-63801-6 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-473-63804-7 (eBook)

Cover Design © Willsin Rowe

www.stephenjohnsonauthor.com

Peace Stick was inspired by Ulrike Fischer, an East German schoolgirl who sought a symbol of hope to cope with the first serious nuclear threat since World War II – the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The book is dedicated to the kinder of the world who suffer the consequences of political folly.

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

Erfurt, Germany

Ingrid Richter shivered; it was cold in the medieval vaulted archway beneath St Ägidien’s Church at the eastern entrance to the Krämerbrücke. It had been five years since she had felt the frosty wind that funnelled through Erfurt’s famous thoroughfare. Ingrid adjusted her merino scarf, an airport indulgence as she had left New Zealand three days ago. Its warmth would have been welcome during her school days almost 60 years earlier.

Cobblestones reflected lights from the three-storey half-timbered shops and homes that lined the narrow bridge. Ingrid watched a group of Americans dawdle past window displays of wines, cheeses, paintings and antiques. She wondered if the tourists understood that many were luxury items when the city was behind the Iron Curtain.

The visitors blocked her exit from the archway as their guide started a spiel. Ingrid was too polite to push through. She listened as the city’s Cold War history was ignored in favour of an architectural monologue about the bridge’s construction – date, width, length and number of homes atop the shops – before segueing into a folk tale.

Ingrid knew it all by heart, plus a few stories that were never shared with tourists. They were the creations of her childhood friend, Sylvie Witzenhause. The Krämerbrücke had been Sylvie’s favourite part of the Altstadt.

The overhanging houses inspired Sylvie to create fairy tales about heroes saving beautiful maidens from horrible witches or goblins. Ingrid had laughed with every new creation; the characters changed but not the theme of a happy ending.

Sylvie vowed that the Merchants’ Bridge would one day be a permanent part of her life, declaring she would only marry a man who could buy her a home on theKrämerbrücke. Sylvie wanted to be the matriarch upstairs while her husband operated a successful shop below.

The sweet reminiscence was suddenly swamped by guilt: Ingrid didn’t know if her friend’s dream had ever come true. It was a regret that niggled on each trip home, the years making it harder to inquire.

The street cleared as the Americans filed down a narrow passage between the first two shops. Ingrid’s heart fluttered. It did every time she saw the ancient access to the river arches; the steps prompted a flashback to a real-life drama involving the despised Stasi. The secret police force had been disbanded in 1990, yet the fear its agents and network of informers generated still caused distress. Ingrid loosened the woollen scarf; the heat flush would pass, but the memory of Pedro’s run in 1962 would never fade.

A bell tower in the distance struck the hour, an indication that Ingrid was late for dinner. The Italian restaurant within the Gildehaus on Fischmarkt was a mere 200 metres away. She smirked; her companions would chide her for picking up bad habits in the South Pacific.

Ingrid admired the décor of the historic building a few minutes later as she shed the scarf and coat. She had never been inside the Guildehaus. Had the timber panels, lights and curved ceilings looked so ornate during four decades under the Socialist Unity Party? She doubted it. The elegant gabled façade had required repairs during her school days that the State could not afford. The priority was to build schools and homes and create jobs, and to control the population.

Belly laughs echoed around the restaurant. The five elderly friends – three men, two women – were seated at a semi-circular maroon banquette. Smudges of sauce on their plates were the only remains of their macaroni, tortellini, and gnocchi dinners.

Two millennial couples at a nearby table briefly lifted eyes from mobile phones where fingers communicated with the world or their dining companions. The digital conversations resumed as the chuckles faded.

The merriment was caused by recollections about arriving for their first school day in September 1956 with the traditional zuckertüte.

‘Gerard stole the best candy from my cone,’ said Kurt Neubert.

Ingrid giggled. She remembered Oma and Opa arrived early to help Mutti and Vati ensure she had the best treats. ‘I saw Oma smack Gerard’s hand away.’

Gerard Mueller shrugged, then smiled. ‘Ingrid had formidable family defences. Kurt’s and Thorsten’s parents were lazy. I got their best westpaket chocolates.’

Thorsten Koehler snorted into his red wine.

Ingrid poked her friend’s protruding belly. ‘Looks like you haven’t lost your sweet tooth. Do you leave candy in your dentist surgery to create more business?’

‘No,’ said Kurt. ‘They’re not tax deductible.’

Ingrid joined the new round of laughter; Kurt smacked the table a little too vigorously, Thorsten steadied the wine bottle. She was pleased the friends had re-established a rapport after years of separation. Her returns had been infrequent following the deaths of her parents. She had seen more of Gerard because their mothers had been lifelong friends. Kurt, a university professor, and Thortsen, a commercial pilot, would occasionally join them depending on their schedules. The wait for a dinner with Petra Stelzer had been much longer: the Berlin Wall was still standing the last time they were together.

‘I was so pleased when Gerard said you were in town, Petra.’ She gestured at the men. ‘I’ve seen these rogues over the years, but that’s because they never left Erfurt.’ She smiled at the slender, ash-blonde lawyer. ‘I understand you rarely get the chance to visit from Göttingen. Are you here to see your family?’

Petra dabbed her lips with a napkin. ‘No. They all moved to Lower Saxony to join me after the wall came down. My company sends me here when it has corporate work in Thuringia.’

Ingrid grimaced. It was an unintended tweak of the emotions; German life could do that with a few words about the past. It was no secret among Petra’s friends that she had hated the socialist regime and the Stasi. She tried to escape with a false passport via Budapest. Hungarian police were told to look for Petra’s red suitcase that had thoughtfully been provided by a friend. Her punishment for republikflucht was a year in jail. Petra was expelled to West Germany upon her release, just a few months before the Berlin Wall tumbled.

‘I’m sorry I never had the chance to say goodbye.’

Petra waved off the apology. The men busied themselves with refilling wine glasses to cover the awkward moment. Ingrid knew Kurt didn’t share the same critical view of the former GDR. The other two were ambivalent. Their careers had flourished during and after the regime.

A waitress arrived to remove the plates, then returned with dessert menus. The distraction gave Ingrid a few moments to recall her attitudes to life in East Germany. She had despised the insidious nature of the Stasi and had been uneasy about aspects of her regimented life. However, she hadn’t shared Petra’s desperation to flee. Her departure was caused by love after meeting a New Zealander working in Berlin; the authorities had granted an exit permit when they married. Brent had been left at home this time as Ingrid was on a business trip.

Petra brought the conversation back to safer territory. ‘Tell me about your job, Ingrid. I hear you are on a recruitment mission. Why would German students go to the bottom of the world to learn English? It would be much quicker to cross the English Channel.’

‘It’s the environmental and lifestyle appeal. Parents believe New Zealand is cleaner and safer, and they don’t mind paying large fees for the opportunity. Many high schools want a share of that market.’

Petra nodded. ‘I can understand the fascination, if not the need to pay a fortune for an education.’ She twirled her empty wine glass for a moment. ‘I wonder what our lives might have been like if we had grown up there.’

‘No different, I’m sure.’ Kurt splashed wine as he pointed around the table. ‘Those two would be still chasing flight attendants and pulling rotten teeth, you would still be a lawyer, and I would still be lecturing bored physics students. The State gave us the opportunities to pursue the careers we wanted.’

Petra’s lips tightened. Would their pleasant reunion descend into a debate about the rights and wrongs of their former rulers? Ingrid was grateful when Petra broke eye contact with Kurt. Acrimony had been averted, for the moment.

Gerard picked up the menu. ‘Help me select a dessert, Ingrid. Should it be tiramisu or panna cotta? Maybe both – and a large bowl of ice-cream. What about you?’

Ingrid laughed. ‘I’m not used to such rich cuisine – a herbal tea will be enough.’

Petra made the same selection, then unexpectedly tapped a new vein of guilt for Ingrid.

‘I thought Sylvie Witzenhause might have been here. You two were such close friends during school. What happened – did you have an argument?’

Ingrid shook her head. ‘We drifted apart when I moved to Berlin in 1972 and she went to teachers’ college. My job as a court recorder left little time – or money – to travel home. I deeply regret losing contact. We lived next to each other for so long that we never developed the habit of writing letters. Communications … just stopped.’

Petra offered a reassuring hand. ‘She had such a fearless approach to life. I can still recall Sylvie asking Herr Schumann to explain the craziness of the Cuban Missile Crisis to a class of 13-year-olds. Do you remember that?’

‘Yes. Sylvie asked him, “Why do the Americans want to drop a nuclear bomb on us because of Cuba?’’ I’ll never forget that.’

Gerard grunted. ‘Wasn’t that a shocking day?’

Ingrid felt it was more like a terrifying week. For the others, she expected the biggest shock was their teacher declaring that World War III could be upon them within a few hours.

Thorsten brushed a lock of artificially dark hair from his forehead. ‘It was so unexpected. The Soviets developing nuclear bombs was supposed to counteract the American threat, not end the world.’

Kurt Neubert nodded, scratched his grey beard. The pot belly, threadbare jacket and wild mane completed the stereotypical ensemble of a professor.

‘The American generals were like rabid dogs, desperate to launch their warheads. They wanted to attack the Soviets and their allies – us – before the missiles were set up in Cuba. It was right that the Russians wanted bases in the Caribbean. The Americans had missile sites in Turkey and Italy. They always had a squadron of nuclear-armed B-52 bombers in the air. The Russians needed to balance that threat. We had good reason to be terrified in 1962.’

Silence descended. Ingrid looked around the table, assuming her friends were thinking about President Kennedy’s television address that revealed that fingers were on the nuclear triggers. The Russians were told to remove the missiles and dismantle the launchers or face the consequences.

That ultimatum was not relayed via the East German media; it was shared by their teacher who risked the wrath of the Stasi to do so. He told his students that fate gave them no voice in the conflict, yet they were the innocents who might die if the nukes were unleashed. Along with tens of millions around the world.

The current tension was eased by the arrival of the desserts. The men eagerly spooned their sugary treats. Ingrid felt pious, but slightly envious, as she sipped her peppermint tea. Petra once again turned the conversation to a safer topic.

‘You lost contact with Sylvie – why would you stay in touch with this old man?’ She indicated Gerard.

‘Because Mutti kept telling me about Gerard’s wealth, hoping to lure me home. But then I found out how many hearts he was breaking!’

That brought more raucous laughter that was missed by the millennials; they had departed, and the restaurant was barely quarter full.

Thorsten paused between mouthfuls. ‘How many divorces is it now, Gerard?’

Two fingers were raised between scoops of tiramisu. ‘I can’t afford the brides like you pilots.’

Ingrid was surprised. ‘You and Steffi have separated, Thorsten? She’s a lovely woman.’

‘Just a trial separation, Ingrid.’

Kurt snorted. ‘Yes. While you trial wife number three!’

Ingrid and Petra shook their heads; the men sniggered. ‘Nothing has changed. You two always had an eye for the girls. I thought both of you fancied Sylvie.’

Thorsten’s lips pursed, Gerard’s eyes sought the Pavarotti portrait on the wall, Kurt sipped his wine. Petra laughed.

Ingrid could not suppress a giggle. ‘Oh no. Not all three of you – I hope it wasn’t at the same time.’

‘The glamour fly boy stole her from me in ’73.’ Gerard’s eyes twinkled. ‘Luckily, I had a spare girlfriend.’

Thorsten pushed his empty dessert bowl to the middle. ‘Sylvie and I had a pleasant summer; we parted as friends. Plus, I knew that Kurt had been secretly lusting after her for years.’

Ingrid looked at the professor; he showed no sign of joining the banter. She thought it wiser to steer the Romeos out of dangerous waters. ‘You boys must have led the Stasi a merry dance.’

‘They followed Sylvie and me to my parents’ Schrebergarten once,’ said Gerard. ‘The cabin window had a thick curtain; they could only guess what we were doing.’

‘Sorry to burst your ego, Gerard.’ Petra replaced her teacup. ‘They probably bugged the cabin after the first visit. Better check your Stasi file; you might find some interesting audio tapes!’

Gerard paled as his friends laughed. It was a rare occasion to find humour in the Ministry for State Security.

‘So, what happened to Sylvie?’ Ingrid raised a stern eyebrow. ‘Did she flee Erfurt in tears after you brutes broke her heart?’

Kurt answered quietly. ‘She married a doctor.’

‘She’s actually a patient of mine,’ said Gerard. ‘Healthy set of teeth, although it’s been about 12 months since I last saw her. She was living on the bridge.’

Ingrid was stunned – her friend’s Krämerbrücke dream had come true. She felt the conflicting emotions of delight and guilt.

‘I walked past her home tonight without realising. Do you know which house is hers, Gerard?’

The dentist shrugged. ‘There are only 32; you could start at this end and door knock your way across and back.’

‘I don’t have the time. This is my only free evening – I have appointments at four schools over the next two days.’

Gerard retrieved his mobile phone from his jacket. ‘I’ll call my receptionist. She can access the office files from her home computer.’ He walked towards an empty area of the restaurant.

‘Maybe Sylvie can join us for a coffee?’ Petra said. ‘I haven’t seen her for … goodness, it must be almost 40 years. I would love to hear about her life.’

Thorsten nodded; Kurt was less enthusiastic. Ingrid wondered if he still carried a torch for Sylvie. His own marriage had lasted five years and there had never been a second trip to the registry office.

Thorsten poured more red wine for himself, Kurt and Gerard, then waved the empty bottle at the waitress. ‘Sylvie was always garrulous. She often opened her mouth without thinking of the consequences. Like that day when Herr Schumann announced the end of the world.’

Petra tsk-tsked. ‘I prefer to think she had an inquiring mind. Sylvie asked the questions that we wanted to know but were too afraid to voice.’

Thorsten turned to their international guest. ‘Was she merely gabby, or truly curious about what brought the world to the edge of destruction that week?’

Ingrid poured tea from her pot as she weighed an answer. ‘I think she was a mixture of both. I often had to hush her in public when she was too loud. Queues outside fruit shops could be risky. She would be saying, “Why doesn’t the Party ensure there are enough fresh bananas and pineapples for everyone? The Party wants us to be healthy socialists.” If something puzzled Sylvie, she wanted answers.

‘The same with the Cuban Missile Crisis. It didn’t make sense that a war between the United States and the Soviet Union over Cuba should involve East Germany. Particularly, why it should threaten us in Erfurt. She didn’t appreciate the risk Herr Schumann took to reveal the danger.’

Gerard returned to the table.

‘Good news. I tracked down Sylvie’s phone number and called her. She’s still living on the river!’ He smiled. ‘She will be here in a few minutes.’ Gerard looked at the empty wine bottle. ‘I hope another Italian red is on the way.’

Thorsten waved acknowledgement of his duty. ‘You have been away so long, Ingrid, yet those school memories are still vivid. Especially Schumann’s bombshell. It was … October … 23, 1962? Was it a Monday or Tuesday?’

Ingrid shivered. ‘You have the right date, and it was a Tuesday. But that horrible week started a day earlier for me. Can any of you remember what we did on the Monday?’

Four blank faces provided her answer.

‘We went to Buchenwald. It was our third visit to the concentration camp.’

Four heads slowly nodded.

‘I have tried to forget those visits,’ said Petra. ‘We were so young to be subjected to that evil.’

The men reached for their wine glasses.

‘I could not erase the memories,’ said Ingrid. ‘The ovens, the inhumane conditions, the hair and teeth the Nazis collected from their victims. Those sights and the shame – Erfurt’s shame for building the crematoria. The guilt stayed with me all the way to New Zealand.

‘I found peace in Auckland. But the nightmares of Buchenwald and World War II were fresh in my mind when Herr Schumann walked into the class the day after our visit. It was the longest week of my life. And Sylvie shared much of that anxiety.’

Ingrid looked at the grim faces around the table and was annoyed with herself. Reunions were meant to be fun, chatty – focused on the good times. She had dampened spirits by dredging up dark days. Cuba had been a shock awakening to the realities of the world.

Had Western children endured the same traumas during that worrying week in October? Did they sit in school in America, England, France, India, Japan, New Zealand, ears open for the shriek of the missiles? Did they lie exhausted in their beds at night wondering if they would awaken in the morning?

Or did they have their own childish rituals, like Ingrid and Sylvie, to give them hope of living another day? A chance to become adults, to bear their own children who would grow up to end the threat of nuclear destruction. Ingrid thought of their solution to the madness engulfing the world.

‘You talk of difficult times, Ingrid,’ said Gerard, ‘yet now you are smiling. What has New Zealand done to your mind?’

Ingrid saw the twinkle in Gerard’s eye. He was always the cheekiest. ‘Kiwis have a quirky sense of humour, but I was thinking about what Sylvie and I did to get us through the crisis.’

Gerard held up his wine glass. ‘We were too young to drink, so what was your solution?’

‘A glücksbringer to save us – and the world.’

Tuesday, October 23, 1962

Erfurt, East Germany

Ingrid butted against the oven door. It would not yield. She was trapped, tangled, unable to free her arms. It was stifling; soon the flames would lick at her feet, her nightdress. Ingrid did not want to burn alive. She was a Thälmann Pioneer, respectful to her parents and loyal to the Party. The Nazis had no right to incinerate an East German schoolgirl in Buchenwald.

A distant voice called: ‘Ingrid!’ It sounded like Mutti.

Ingrid wanted to reply, ‘I’m here inside the Nazi oven. Save me, Mutti!’

The plea would not escape her lips. She pushed again with her knees and shoulders, her face rubbing against the metal plate. She felt the raised metal of the horrific words emblazoned there. Her eyes were closed, but she knew what they said:

Maschinenfabrik

J.A. Topf & Söhne

Erfurt

Ingrid was being burned alive in a crematorium furnace made at the factory a 15 minute-walk from her family’s apartment in Friedrich-List Strasse. How cruel was that?

‘Ingrid! Hurry up!’

Mutti was close.

‘Save me, Mutti! Save me!’

Was her scream contained in the claustrophobic chamber, or were the words barely a whisper because of the lack of oxygen? Mutti would never know her only child was inside the death oven. Her strength was fading; the wriggling and squirming could not open the oven door. The flames would engulf her any second.

Light! Freedom! Coldness!

Exasperation.

‘Wake up, child! You will be late for school, and I need to get to the shops. I promised your father soljanka for mittagessen.’

Eyes opened to find Mutti nursing the feather bettdecke, the cold spreading through Ingrid a motivation to obey. There was no heating in the mornings, and the single-glaze windows were unable to deflect the autumn chill.

It had been a nightmare; a reaction after a school trip to one of the horrors of Hitler’s Third Reich.

The palpitations slowly subsided as Ingrid watched Mutti fold the thick comforter. The sheets were straightened while she gathered warm school clothes: cardigan, white blouse, pleated skirt. Should she tell Mutti about her terrible dream and what she had learned at Buchenwald yesterday?

‘Wash yourself and have breakfast. I’ve sliced and buttered your bread; there is marmalade or honey. The milk has been poured.’

Mutti swept through the curtain wall of Ingrid’s bedroom, officially called the middle room. It connected to the master bedroom on one side, the lounge on the other. There was no cause for complaints about lack of privacy. The Party had treated them well: the apartment was big for two adults and a child. They also had a kitchen, bathroom and a little room that frequently was rented to people in need. The housing shortage in East Germany created by air raids during the war was taking a long time to resolve.

Vati had already left for work at the tailor’s shop and Mutti was too busy tidying the apartment to talk about childish dreams. Ingrid resumed her morning routine, suppressing the terrors the compulsory concentration camp visit had unleashed. Ingrid wondered if any of her friends had experienced a similar night.

‘Sylvie was shocked. Maybe she had bad dreams too?’

The question was rhetorical as Mutti was in the master bedroom with the sweeper. Ingrid could hear it clatter over the timber floor, then go quieter as it rolled over a carpet. Talking aloud as a single child was acceptable, according to Oma. Her grandmother said it was good to share thoughts with the universe; sometimes it provided solutions to life’s mysteries.

At least Sylvie would listen as they walked to school. The wall clock told her she had five minutes to finish her meal, brush her teeth, pack her leather schulranzen and meet Sylvie next door outside Number 11. Any longer and her friend’s lips would be turning blue from the cold.

Sylvie’s winter jacket was not as warm as Ingrid’s. Mutti was a gifted seamstress; she had cleverly fashioned many warm winter clothes from westpakete. The regular care packages from Mutti’s family in West Germany had been their only access to luxury items since the Berlin Wall completed the Iron Curtain just over a year ago.

Ingrid looked at her breakfast. Usually she would have gobbled it down, but today her stomach was churning after the dream. Yet she could not throw the food away. What would the captives at Buchenwald think of this meal? Was it more than they were given to eat in a day? A week? She could not imagine trying to survive on stale bread, watery soup and scraps.

Ingrid ate quickly, thinking her Pioneer leaders would be proud of her. She was a good young citizen. However, a wrinkle in that relationship had surfaced at Buchenwald. The Party was lying to Ingrid and her school friends.

She had not been able to tell Sylvie about that revelation yesterday on the journey back to the 31st Oberschule. It was about 20 kilometres from Weimar back to Erfurt, plenty of time to share reactions to what they had seen, felt and smelled. Ingrid was sure the odour from the ovens lingered still, 17 years after the last fires had been extinguished. She could almost taste the ash on her tongue.

But nobody had spoken from the time the class exited the camp gates until they separated at school. Not even a whisper between best friends. Herr Schumann had sat alone at the front near the driver. Ingrid noted his gaze never left the road ahead, no glance in her direction, seated next to Sylvie; nothing to indicate the horrific moment they had shared in front of the crematorium.

It was the third time they had seen the horrors of the camps. The shame that had been carefully nurtured by the State was overwhelming. Silence was a temporary balm, even on the walk home from school. But Ingrid knew she must tell Sylvie what she had learned.

The Monday musings swirled through Ingrid’s mind as she completed the school preparations. Mutti had made a gherkin sandwich for the long break, enough to sustain her through to the soljanka at lunch. Ingrid pulled her thick coat from the stand and buttoned it to her neck. It reached her bare knees; it was chilly outside, although not yet time for tights. They had to be used sparingly as Mutti preferred to create lovely fashion rather than spend all night darning rips from outdoor adventures. A cloth beanie matching her coat covered her blonde bob. The satchel, with homework and sandwich, was slung on her back.

The sweeper paused momentarily as it moved from the middle room to the lounge.

‘Bye, Mutti.’

‘Have a good day, Ingrid. Study hard.’

The sweeping resumed as Ingrid ran along the tiled hallway and burst from their ground-floor flat. She never had to look for vehicles in the driveway; none of the six families in the apartment building owned a car. Vati said the waiting time for a Trabant was several years. Besides, most of the important places in Erfurt were within walking distance. There were regular trams for visits to their Schrebergarten, or the leafy Steigerwald, and her grandparents’ home in the northern suburbs.

The school was 15 to 30 minutes away, depending on their chatter and the temptations. There were three bakeries between home and the classroom; fresh bread smells were often hard to ignore.

There was no time to dawdle today. The kitchen clock had shown 7.10am as she’d left, and first bell was always punctual at 7.30. Failure to make the class line in the courtyard would result in detention.

Tomas Schumann

It was chilly in the second-floor apartment in Anger on the edge of Erfurt’s Altstadt. Heat from the ceramic kachelofen in the living room had died about an hour before midnight. Tomas Schumann considered the morning air bearable enough to avoid wasting precious briquettes until he returned from school. He had endured colder conditions in Belgium during the Weltkrieg.

Schumann took his breakfast bowl and coffee mug through to the kitchen. He was a man of routine; wash, drain, dry, listen to the news report on the bakelite radio. It was tuned to West Germany, as usual. The enemy could be relied upon to provide a wider perspective of world politics and events. It was illegal to listen to Western broadcasts in the German Democratic Republic. The Ministry for State Security would never know if he kept the volume low – unless they had microphones in the wall.

He rinsed the dregs of his oats – then dropped the bowl onto the sink. It didn’t shatter, but Schumann felt the world was about to fracture. The broadcaster announced that the Soviet Union and the United States were on the verge of nuclear war. The simmering Cold War was about to boil over – in Cuba, of all places.

He pulled a pine chair from the table closer to the radio and listened. President Kennedy told his nation the previous night that the Unite States had evidence the Soviets were building missile sites in Cuba. Schumann understood the implications: Soviet nuclear warheads could reach every major American city within minutes.

‘You old fox.’

Nikita Khrushchev had sneaked a nuclear arsenal into America’s backyard – but it could blow up the world.

‘You silly old fox.’

The radio volume was increased. Why worry about the Stasi when Armageddon could be mere hours away? Schumann was not normally inclined to morose thoughts about mortality. He had been a soldier in two world wars; the first out of patriotism, the Nazis gave him no choice the second time. Schumann survived both conflicts and the current dictatorship by being adaptable: keep your head down, don’t be a target, follow the rules. They were simple tactics, yet enough to keep him alive in the muddy trenches of Flanders, the dying days of the Third Reich and the police state Erfurt found itself inside after the Soviets liberated them from the Nazis.

The radio announcer revealed President Kennedy’s first response to the Soviet expansion: a maritime and air blockade of Cuba.

‘Khrushchev won’t accept that.’

The announcer would never hear the rising anger in the rattled teacher.

‘The idiots.’

Schumann listened to more extracts of Kennedy’s speech.

‘This urgent transformation of Cuba into an important strategic base by the presence of these large, long-range and clearly offensive weapons of sudden mass destruction constitutes an explicit threat to the peace and security of all the Americas.’

English was not taught in his school, but the teacher had secretly sustained his language skills via the US Forces radio and a stash of Western thrillers. He noted a more belligerent tone in Kennedy’s address, a contrast to the humiliation dished upon on the new president after the Bay of Pigs invasion and the closing of the Iron Curtain.

‘You’ve pushed Kennedy too far, Mr Khrushchev.’

His shoulders sagged. For so long the Cold War focus had been Europe. Berlin had been a canker on the Soviet’s bum since the Nazis defeat in 1945 led to the joint occupation. The recently built wall was the flashpoint where bullets were already being fired, mostly at East Germans trying to escape to the West. How long would the world tolerate that open slaughter? Schumann and his closest friend, Jürgen, often debated when retaliation would escalate from rifles to rockets, sucking a war-ravaged continent into another maelstrom. And yet it’s Cuba where political folly has pushed us to the edge of the abyss.

Schumann rose slowly from the seat as the bulletin ended. He switched the radio off, but it did nothing to quell the fear.

‘What about the kinder?’

His students, the dozens of young teens who were his primary responsibility in life, and his greatest joy. President Kennedy indicated he was prepared to use military action to remove the Soviets. He was setting everyone on the path to World War III. That could be minutes, hours or days away. One nuclear superpower had thrown down a gauntlet to the other – who would pull the trigger first?

It was with a heavy heart that Schumann packed his satchel for the day’s lessons. 7A was his first class – would they know anything about this threat? Should they know?

Ingrid Richter

‘Hello, Ingrid!’

Sylvie was waiting across the driveway. She was the same age – 13 – and roughly the same height as Ingrid, although they were never mistaken for sisters. Her wavy blonde hair was shoulder length, neatly capped by a mütze similar to Ingrid’s. Fingers were tucked into armpits, her feet dancing a jig to keep her warm. Sylvie’s grey jacket was thinner and older, made in East Germany. Her family had neither relatives in West Germany to send westpakete nor a clever seamstress to shape any traded Western cast-offs into practical fashion for a growing daughter.

‘Morning, Sylvie.’

They fell into step, crossed tree-lined Friedrich-List Strasse, ignored the first bakery across the road – it was too close to home – and were immediately at the first turn onto Bodelschwinghstrasse.

There were few cars; pedestrians and children were hustling to beat deadlines. The sky wore its familiar October grey blanket. There would be occasional sunny days in the months ahead but little warmth until spring. The first snow was a few weeks away.

The smell from the brewery near the Stadtpark, two blocks north, was normally welcome. Ingrid loved the aroma of the hops, malt and yeast they used to make beer, but not today, the morning after visiting Buchenwald. Her stomach roiled again.

They walked close, thumbs and fingers wrapped around the straps of their ranzen, occasionally bumping shoulders. ‘How did you sleep last night, Sylvie?’

‘I was okay.’ Sylvie sucked on a strand of hair, an annoying habit that highlighted its length. Her mother allowed Sylvie to grow it longer than most girls in middle school. ‘I was upset – like you – by the concentration camp. But I tried to distract myself by reading a story from Struwwelpeter.’

Ingrid knew the classic children’s collection well. Heinrich Hoffmann’s book may have been more than 100 years old, but its stories were still entertaining.

‘I read ‘The Story of Flying Robert’.’

‘You wanted to forget the horrors we saw? By flying away in a storm with Robert’s umbrella?’

Sylvie nodded. ‘It was a nice thought. I imagined myself being blown south, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. It’s hot and sunny all year round in Fiji. The temperature is always 30 degrees.’ She pulled her coat tighter. ‘I would never have to be cold again. Coconuts fall from the trees. I could eat pineapples and bananas every day, not have to queue at the fruit shop when they receive a shipment. Did you know Germany used to have a colony in Samoa?’

Ingrid shook her head. They reached the intersection with Tschaikowskistrasse. That would take them left, closer to school, if they walked past one of their favourite bakeries.

‘Do we have time for a schweineohr?’ Sylvie jiggled a few pfennigs. ‘I don’t have enough for an éclair today.’

Ingrid preferred the chocolate and cream treat over the pig’s ear-shaped pastry, but neither appealed.

‘We don’t have time. Maybe after school. My tummy is feeling a bit strange.’

Sylvie slipped the coins into a pocket and crossed the road, Ingrid in step.

‘You were very pale after our school trip yesterday, Ingrid. Did you dream about the concentration camp?’

Ingrid looked around. The street was quiet, just a few men gathered around the entrance of the third bakery at the next intersection. That was unusual at this time of the morning. Normally, the men would buy bread rolls and hurry to work.

A schoolgirl conversation should not be of interest to adult factory workers. Yet, every child had been drilled about the need for discretion with public chatter. The secret police had ears everywhere; anti-social comments or criticisms of the Party would be reported to the Stasi regional headquarters on Andreasstrasse. Ingrid was always anxious when the apartment block’s doorbell rang at night. The fear probably stemmed from watching movies about the raids of the Gestapo. She would hold her breath until a friendly voice was heard.

Ingrid’s reply to Sylvie was barely more than a whisper. ‘I had a nightmare about the ovens at Buchenwald. I was trapped inside – the flames were burning my feet and I could not escape. I was pushing the metal door, but it wouldn’t open. I was so panicky – why would the Nazis want to burn me alive?’

Sylvie stopped, placed a hand on her friend’s arm. ‘That’s awful. How did it finish?’

‘Mutti pulled the bed cover off – that woke me up.’

Sylvie grimaced and resumed walking. ‘I understand we need to learn the history of the camps. Germans will carry that guilt forever. But I don’t think it’s right to show those awful places to children. We might all have nightmares, and not everyone has an umbrella like Robert!’

The image of a generation of East German kinder flying to the Pacific made Ingrid snicker. She should really tell Sylvie about the most shocking discoveries – that the ovens for burning humans had been designed and built just a few streets away, and that the State had lied about their Russian liberators. The mood of the men at the bakery kept her lips closed.

There were three factory workers – judging by their cloth caps, dark jackets, and trousers – at the entrance to Herr Wenkell’s shop. The large baker was standing with them, a smattering of flour on his arms and hands. That was strange; Ingrid had rarely seen him outside the bakery. And he was not smiling. Every customer, whether adult or child, was treated to a hearty greeting by Herr Wenkell. Not that morning. The four men spoke quietly, concern on their faces as the schoolgirls walked past unnoticed. Their low volume was an indication the topic was sensitive.

‘Something is wrong.’ Sylvie waited until they had rounded the curve into Häslerstrasse to break the silence. That was a rare show of discretion from her friend. Another day she might have blurted her statement within earshot of the men, any one of whom could have been a Stasi informant. ‘Herr Wenkell looked worried – they all did.’

Ingrid glanced over her shoulder. The group had broken up, the workers scurrying towards the Stadtpark, most likely to jobs at the brewery. Herr Wenkell had not moved. He stood with hands on his hips, looking at the sky.

‘Perhaps someone has died?’ Sylvie wrapped her fingers back around the ranzen straps. First bell was close. ‘Maybe it was a work friend?’

That was a logical explanation, Ingrid thought. Although, the baker’s change of routine was puzzling. It was cold, and Herr Wenkell had a short-sleeve shirt under his apron. Yet he was still on the pavement staring at the clouds.

Within a few metres, the curving street obscured the bakery. Ingrid was about to return to her crematorium experience when Sylvie changed tack.

‘You should dream about Pedro tonight. That’s more pleasant than concentration camps.’

That suggestion caused a flutter within Ingrid’s chest. It happened every time she thought of Pedro or heard his name mentioned. Only two other companions knew that the Cuban had stolen her heart. Sylvie had never met him; Renate Heyn and Katja Reigel had been at the summer camp on the Baltic Sea where the handsome Pedro Barios and his companions had charmed the young allies.

‘Perhaps we should go for a walk in the Altstadt after school? We might see him at a café on the Domplatz.’

‘Don’t be silly, Sylvie.’ Ingrid hastened the pace. Am Schwemmbach was a few metres away, the school entrance not far along the main thoroughfare. ‘Pedro will be too busy with his studies to sit around drinking bad coffee.’

Ingrid’s cheeks flushed, although not from the walking. Everything about Pedro was so exotic: his Latin heritage, caramel skin, the silky accent. She had been captivated from the moment the Erfurt trio encountered the Cubans at the coastal campsite in Glowe.

There was no need for Sylvie to know about her two fruitless visits to Erfurt’s main plaza to find Pedro before classes had resumed. Pedro lived and studied at the Pedagogical Institute north of the Altstadt, where teachers were trained. Pedro was 20. He was a true gentleman who would one day return to his homeland to teach young socialists. That was his destiny. She would always respect Pedro Barios and never forget him.

Soon the girls were surrounded by other students ranging from six years of age to their mid-teens, all hurrying to stand in line before the bell. A low brick retaining wall to their right marked the school boundary; a walkway under the first-floor classrooms would usher them to their destination.

Ingrid paused to look at the façade. The 31st Oberschule was barely half a dozen years old, but there was nothing to admire in the concrete building. It was squat, grey and functional. Large windows allowed plenty of light; students would swelter on hot days; the radiators worked extra hard in winter to keep the rooms warm.

There was nothing unusual about the courtyard mood. Pockets of conversation and laughter were stifled when the bell rang, and the students proceeded in orderly lines to their classes. 7A, with Herr Schumann, was on the ground floor.

Their teacher was not waiting for them. They were responsible for unpacking books and pens, assuming their regular seats and preparing for the second bell. Herr Schumann would then stride in and take charge.

Gunther Kist

The Ministry for State Security regional headquarters on Andreasstrasse was buzzing as Gunther Kist entered. Pockets of agents and support staff gathered around desks, talking animatedly: arms waving, heads shaking, feet shuffling. Kist had not seen that level of excitement since August the previous year when the Berlin Wall went up. That had been a wonderful time. They could finally put the squeeze on the Western ghetto in their midst. It was only a matter of time before the GDR took full control of the old capital.

Kist headed for his desk near the window. Few colleagues bothered to break their conversations to acknowledge or greet him. He knew many considered him surly and single-minded. That never bothered Kist; he was a proud sword and shield of the Party; he had no time for frippery. The chameleon skills of a veteran agent had been carefully honed; he was able to blend in anywhere with a few subtle wardrobe changes. His job was to watch and listen, not be gabby. That was the way to weed out enemies.

One constant through all the office conversations he passed was the word ‘Cuba’. Kist knew about the recent revolutionaries living close to the United States. He might struggle to point to Fidel’s socialist paradise on a map, but he was aware of its strategic location. Cuba was a communist irritant up the Americans’ bum, much like West Berlin was to the GDR and the Kremlin. What was happening in Cuba? Kist had not listened to the radio before leaving the apartment. Had he missed an important Party announcement?

‘Gunther!’ Carsten Hartwig, his immediate superior, gestured towards an empty chair at his desk. ‘Have you heard about the situation in Cuba?’

It was an awkward moment. Kist worried he might be seen as lazy, not keeping up with important events. Bluffing was not in his nature.

‘No. I heard comrades discussing Cuba on the way in.’ He waved an arm at the room behind. ‘But I have not seen anything official.’ That was a safe reply. Kist was waiting for a superior to brief him.

‘Our Soviet allies have been caught out. They have been stealthily setting up missile bases in Cuba and the Americans have just spotted them.’

Kist reeled. ‘That … is surprising.’

Hartwig laughed at the agent’s reaction. ‘You must be the only one who doesn’t listen to West German radio broadcasts.’

‘They are a corrupting influence. I know as a Stasi agent I can listen, but I dare not expose my family to such treason.’

His superior dismissed the comment with a wave. ‘Yes, that is understandable. But if you don’t know what the enemy is talking about, how will you know where to look for threats to the Party?’

Kist squared his shoulders, sat straighter. ‘Corruption lurks everywhere. We do not have to look far for traitors, black marketeers and Western liberals.’

Hartwig shrugged and shuffled a page on his desk. ‘Okay. Well, the gist of what is happening is this – the United States is about to blockade Cuba. They are threatening to search every Soviet vessel that approaches the island.’

‘That’s piracy!’

‘A little more serious than that, Gunther. The Americans want any missiles already in Cuba removed and the launch sites dismantled. If Khrushchev refuses or retaliates to US naval intervention, we could be, to paraphrase President Kennedy, on the edge of a nuclear abyss.’

Kist was stunned. A nuclear firestorm initiated by the Cuban situation. Surely it would never come to that. He understood that launching a nuclear weapon could push over the first domino and the rest would follow in order, leaving a smoking planet. He struggled to accept that the Soviet or American leaders wanted that to happen.

‘Anyway, those decisions are above our pay grade. We deal with what our officers require.’ He handed a typed document to Kist. It had three names. ‘You know we have several Cuban students at the Pedagogical Institute?’

Kist nodded. ‘I followed them for a few days when they arrived. They were good students, loyal socialists.’

‘The Colonel wants to make sure that is still the case. The Party doesn’t want them to think they have a better chance of survival in a West German shelter.’

Ingrid Richter

Ingrid and Sylvie sat side-by-side at a table in the second row. There were 28 in the class; a glance confirmed all were present, and none showed signs of suffering side-effects from their Buchenwald visit. Was I the only one to have a nightmare? Ingrid wondered.

The tall figure of Herr Schumann appeared in the archway. He stopped. Normally he arrived with an air of authority and marched to the front of the room, ready to launch into the first 45-minute lesson. Not today.

He wore the familiar buttoned, single-breasted grey jacket and trousers, tailored by Ingrid’s father from a westpaket in April. The black shoes were polished, although the white hair was untidy. There was no wind outside; the locks looked as if fingers had been raking the thinning locks.

Student eyes looked in all directions, seeking guidance from confused classmates. Should they stand or wait for Herr Schumann to move to the front of the class to initiate the morning ritual? Ingrid looked to their Thälmann Pioneer leader in his blue neckerchief. Hans Rathmann was half out of his seat, unsure about a break in the routine established from their first week at school.

Herr Schumann was old, at least 63. Ingrid had heard him talk about retirement in two years when Vati did the measurements for his suit at their apartment. He wanted to play more chess and devote time to his stamp collection. Mutti and the teacher occasionally traded special stamps. His hobbies were frequently disrupted by the demands of school life: essay marking, outings and State-initiated campaigns to prepare loyal young citizens.

The teacher ended the dilemma for his students by walking slowly to his table. They all snapped to attention.

Hans Rathmann was able to address his classmates. ‘Be ready!’

‘Always ready!’

The reply came with less than the usual gusto.

Hans turned to their teacher. ‘I report that 7A is ready for the classes.’ He saluted and resumed his seat.

Herr Schumann nodded. He stood with hands clasped behind his back. That was standard, although Ingrid noticed the shoulders lacked their usual military bearing. He had been in both wars; he told them before the Buchenwald visit that a wound from the first had restricted his service in the second until the final desperate months.

It looked as if Herr Schumann had received bad news, like the men outside the bakery. Ingrid thought back to Buchenwald and the private revelations that had shocked and caused her nightmare.

Had revealing those secrets affected her teacher? It was a risk to share knowledge contrary to the doctrine of the Party. Was Herr Schumann worried that Ingrid would be indiscreet or, worse, that she might report him to the Stasi?

She sought his eyes. They were directed at a spot on the wall behind them. He stood silently, as if trying to form words to start the lesson. No, Ingrid did not believe it was the camp that had spooked their teacher. Herr Schumann had visited many times with different classes. He had experienced the horrors of war. There was something else on his mind.

Ingrid glanced to her right. Gerard Mueller was at the next table with Kurt Neubert. They looked bewildered by Herr Schumann’s hesitant start, yet neither would question their pedagogue. Probably the only student who would do that was Sylvie. Ingrid placed a hand on her friend’s arm as she sensed that was about to happen. No need to make eye contact, the message was clear: let Herr Schumann talk when he was ready.

The teacher moved to the front of his table.

‘Class, I have some news to share. I’m sad to say you will find it shocking.’

Several students gasped.

Herr Schumann swallowed.

Ingrid willed him to continue. What was so bad that it rattled their normally calm, confident figurehead? He had survived two world wars – what could be worse than that?

‘I have been wrestling with my conscience about whether to share this information.’ He placed his hands inside his trouser pockets, an informality never witnessed in the classroom. ‘What I have to say affects you – indeed everyone inside and outside of the German Democratic Republic. You have a right to know the truth. Your lives depend on it.’

More gasps. Sylvie gripped Ingrid’s hand.

‘I am afraid to say we are on the brink of World War III. We are facing a thermonuclear onslaught from the imperialist aggressors, the United States, directed at our Soviet … allies.’

Howls of surprise rippled around the room. Ingrid wondered about the pause between ‘Soviet’ and ‘allies.’ She had witnessed a fracture in Herr Schumann’s party loyalty at Buchenwald. Was it now a chasm?

Crying could be heard from a table nearby.