6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wolsak and Wynn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Set in southern Ontario during the 1980s, acclaimed poet Catherine Graham’s debut novel is as layered as the open-pit mine for which it is named. Only child Caitlin Maharg lives with her parents beside a water-filled limestone quarry, but her idyllic upbringing collapses when she learns her mother is dying. After a series of family secrets emerges, she must confront the past and face her uncertain future. Lyrically charged, jewelled with images, and at times darkly comic, Graham’s prose weaves a mysterious, hypnotic tale of loss, deception, and the courage to swim the depths of life alone.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 319

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

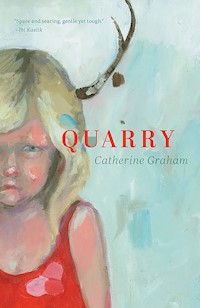

Cover

Set in southern Ontario during the 1980s, acclaimed poet Catherine Graham's debut novel is as layered as the open-pit mine for which it is named. Only child Caitlin Maharg lives with her parents beside a water-filled limestone quarry, but her idyllic upbringing collapses when she learns her mother is dying. After a series of family secrets emerges, she must confront the past and face her uncertain future. Lyrically charged, jewelled with images, and at times darkly comic, Graham's prose weaves a mysterious, hypnotic tale of loss, deception, and the courage to swim the depths of life alone.

Also by Catherine Graham

Also by Catherine Graham

The Celery Forest

Her Red Hair Rises with the Wings of Insects

Winterkill

The Red Element

Pupa

The Watch

Title page

Dedication

for John Coates

Prologue

Dive in. Turn to water before it freezes.

Contents

Cover

About This Book

Also by Catherine Graham

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Contents

Chapter 1: Nobody

Chapter 2: The Pink-Shingled Cottage

Chapter 3: Red Bars

Chapter 4: Lifeguard

Chapter 5: QT

Chapter 6: The Royal Connaught

Chapter 7: Three in a Room

Chapter 8: Special

Chapter 9: Don’t Swallow

Chapter 10: Nervosa

Chapter 11: River of Hands

Chapter 12: The Watch

Chapter 13: Old Tennis Players Never Die They Just Lose Their Balls

Chapter 14: A Wound on Top of a Wound

Chapter 15: Figure and Ground

Chapter 16: Valentine

Chapter 17: Vase or Two Faces

Chapter 18: Turn to Water Before It Freezes

Chapter 19: Sound Is a Body of Water

Chapter 20: Water and Stone

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Nobody

I didn’t know what a quarry was until I saw the one that would belong to us. A pit carved for mining. Dig what you need – the dynamite gap – leave a hole for evidence. Don’t think about air filling it up. Air fills up everything. Water makes the quarry more than it is; the blue we were drawn to. On the dock, looking out. My mother on one side. My father, the other. Their big shoulders pressing me in.

It was our first summer living beside a lake that wasn’t a lake, with wind tents of blue moving in the jewelled sunlight, up and gone and up again. The limestone, cut into jagged rock, layered with the weight of dead animals, ancient sea animals, imprints. Lush green trees, they surrounded as a forest. Dad had found the place by chance after spotting the For Sale sign outside a white gate that led to a long gravel driveway, a bend that led to a mini-lake, the house of Mom’s dreams.

We made up dives that summer, me and Cindy. The Watermelon Dive – legs in a V. The About-to-Die Dive – a rambling, dramatic shotgun death off the dock. The Scissor Kick Dive – a flutter of pointed legs in the air. And the Drowning Dive – rise to the surface and float like the dead fish that smacked against the limestone rock, oozing decay’s stink. With a two-year advantage, I gave my nine-year-old cousin a three-second head start whenever we raced off the dock to reach the floating raft. Sometimes a hit of the giggles cut through my determination – a memory of something we’d laughed about while lying in the dark, tucked in single beds, or while eating Rice Krispies, opening up our food-filled mouths to shout: see-food diet!

Mom served as judge as she sat on the dock smoking her brand, Benson & Hedges. She was there to rescue us if we were to drown. I knew this was an illusion. Though an athlete, Mom could barely swim and deep water scared her. She excelled at land games, sports with racquets like badminton and tennis, especially tennis. Our shelves of knick-knacks were stacked with gold trophies, tiny females frozen in mid-serve.

“Watch, Mom. Watch!”

“Caitlin Maharg, I’m always watching.”

I dove and then Cindy dove and we made her grade us.

“Ten out of ten,” said Mom.

“Me or Cindy?”

“Both.” She lit another cigarette and exhaled the burst of smoke.

“Aw, Mom! Someone has to win.”

Despite her fierce competitiveness on the tennis court and my constant pleading, she refused to budge. We always came out even.

When we got tired of diving, we swam like the darting sunfish, the smallest fish in the quarry.

Standing on tubes was something Cindy could do better than me. Her smaller build gave her an advantage. I could stand on an inner tube, no problem, but my balance wouldn’t last like hers. My long legs wobbled like the egg-shaped Weebles we played with on the floor of Cindy’s Burlington bedroom when we weren’t spying on her two older brothers. My Uncle Jim’s new job had brought the Brant family back to Ontario, all the way from Calgary. Because they’d been so far away, I’d never thought of them as family until now.

Dad didn’t like to swim. When he did go in the water, to work the stress off himself or shampoo his grey-peppered hair, he stayed within arm’s reach of the dock ladder. Because his arm was so long, like all of his limbs, he looked farther away than he really was.

When the water was still, you could see rock bottom. But you couldn’t touch it, not off the dock – feet had no resting place. On clear, windless days we watched the carp suspended below, like sunken logs or torpedoes. They never did anything. In fact it was us that scared them, our manic splashes getting in and out of the water, our specialized dives. After the water settled again, Cindy and I would try to find them, but they’d long disappeared.

Sunfish never scared. Surface swimmers, they hovered by the dock with the constant hope of being fed. Desperate nibblers, they mouthed anything, including Mom’s cigarette butts, though they always spat them out. Sometimes we felt them nibbling our toes – a safe sensation when we sat on the dock and could see the source of the gummy tickle, but when it happened inside the quarry, as we treaded water or floated on our backs, the Jaws theme song ran through my head, and I imagined the deadly ones – catfish with snake-like whiskers, serpent-shaped muskie with sharp teeth or the turtle with the jaw that could snap your big toe off.

The quarry wasn’t always stocked with fish. There were no nearby rivers or tributaries to lead bass, sunfish, perch and more to the lake-sized pit. Dad said previous owners had put them there. And because there were few predators, each species grew in number, including the deadly ones. But Cindy and I were pretty good at waving away the darker things. We had each other and a mother able to watch us.

When Dad came home from work those summer evenings, he watched us too. Barefooted and bare-chested in his blue swimming trunks, he was eager to take in the rest of the day before the sun lay her red blade.

“Let’s see your dives,” he said.

I dove and then Cindy dove, and after he judged us both, Cindy won. No ties. She gloated silently. Her face, all smile. Not mine. My face, all scowl like my body.

“Not fair,” I mumbled, sitting at the dock’s edge. I dunked my feet in the water. When I looked downwards, I saw the alarming cut water makes where it meets air; my legs disjointed like eyes unable to see a faraway sight; eyes out of tandem.

“Don,” said Mom in that soft tone he listened to. But then, he listened to all her tones.

“It’s only a game, Rusty, for God’s sake.” He chuckled to make things light.

No way had Cindy beaten my Watermelon Dive. She couldn’t split her legs in the air like me. Why was he making me lose? Was it because Aunt Doris beat him at swimming games? Dad never played with my feelings when we were alone, just the two of us.

There we were, driving down Grimsby’s Main Street with the top down on the Malibu, the summer sun over our heads (Mom at home, fast asleep after her night shift in the ICU), doing Saturday errands. The AM radio blasting out our favourite pop songs: “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree” and “Love Will Keep Us Together.”

Why was he making me lose? Why was I letting him be the judge of me?

I was the one Dad got mad at when Cindy left her wet bathing suit on top of the bed or when he found her damp swim towel balled on the bathroom floor. She smiled with subtle pleasure when she saw my freckled face redden.

Is that what it was like having a sister? Before Cindy came to stay with us that August, if I wanted the last Hello Dolly in the pan I got it. If I wanted to sleep in the other twin bed (my own sheets wet from night sweats), all I had to do was hop over. And when my parents sat on the dock, it was me they watched. My smooth front crawl, my perfect toe-pointed dives, my back-and-forth endurance. My skin prickled and my mouth scowled when praise went to her.

“Wanna play tubes?” Cindy asked, still treading after her win.

“No,” I said, turning to Mom. “We have to eat, right?”

Mom looked at her inner wrist to see the watch face; the old habit lived on from when she used to take patients’ pulses in the ICU. “The wings won’t be done yet. You have time.”

But playing tubes meant standing on them for as long as possible. Another game I wasn’t prepared to lose, my feelings too fierce to balance properly.

“Race you to the raft,” I said in a rush. I would win this game and he couldn’t stop me.

“No,” said Cindy, grinning. “Think I’ll float for a while.”

My scowl returned.

I tried to imagine Dad as a boy. “Your father was gangly like a weed,” Aunt Doris said the day she dropped Cindy off for her summer stay. She told me he was good at sports, especially baseball. With those long legs of his, he could whip from base to base. But he panicked in water when he couldn’t touch bottom. When I’d asked my aunt why, she told me what happened off the dock at Baie-D’Urfé where they grew up, in a house right across from the lake, how Dad and his buddy Louie were out paddling in a canoe one day when Louie stood and started rocking the boat and it tipped. Louie could swim but Dad couldn’t. Somehow during his drowning panic, Dad’s long arms hit the upturned canoe and he held on.

If that happened to me, I wouldn’t have to hold on. I could float or tread water or swim to shore.

“No swimming today, I’m afraid,” Mom announced later that week. She was sitting and smoking in her chesterfield nook, her legs curled up. She was looking out the family room window at the pelting rain. “No tennis for me.” She sighed.

Since our move to the quarry, she hardly played the game she loved and excelled at. As a little girl, I spent hours watching her through the diamond-link fence. Pock! Straight from the racquet’s heart, the sweet spot, the perfect shot. My Malibu Barbie and I silently cheered.

Cindy plonked down beside me on the chesterfield. “Scoot over,” she said, nudging me in the ribs. “What should we do?”

I nudged her back before waving away the annoying cigarette smoke. “Don’t know,” I said. I wanted to swim. I wanted the rain to stop.

Mom lit another cigarette, inhaled and exhaled. “Why don’t you girls play Monopoly? The game’s in the hall cupboard.”

Cindy followed me – out of the family room, through the living room and down the back hall of our bungalow. At some point the sound of her soft footsteps behind me stopped. She’d slipped into the master bedroom.

“What are you doing?” I said, stepping on the plush blue carpet.

“Pictures,” she said, scanning the dresser, bureau and matching bedside tables. “My parents have wedding photos … yours don’t have any.”

I thought back to her parents’ bedroom, a room I knew well from our games of hide-and-go-seek. The window’s floor-length curtain, where I hid my stilled body, smelled of ripe peach. Everything in their house smelled fresh and clean. There were wedding photos on the master bedroom wall and dresser. “So what,” I said. “They eloped. They didn’t have a wedding.”

“Elope. Ha! Cantaloupe, antelope.” She grinned and waited for me to laugh.

“You don’t know, do you? You marry but not at church. A judge man does it, someone like that.” What did Mom say? A justice of the peace? I folded my arms across my chest. I didn’t want to continue this conversation but didn’t know why.

“Aunt Rusty and Uncle Don don’t wear wedding rings.”

I thought of Mom’s bare hands. Dad’s tiger-eye ring.

“Dad does.”

“That’s not a wedding ring.” Cindy pushed back the blue sham on the king-sized bed and pulled off a pillowcase, then draped the cotton slip over the back of her head, her long brown curls. “How do I look?” She leaned against the cedar wall for a long moment before proceeding down her pretend aisle. I stepped forward. “No, stay there,” she ordered. “You’re the groom.”

“I don’t want to be the groom.”

“You have to be the groom, you’re taller.”

She came toward me, pausing after each step, singing these words: “Here comes the bride.” I hated that song. For some reason it made me think of funerals, though I’d never been to one. “Stop it. I don’t want to play this stupid game.”

Mom and Dad never talked about their elopement unless I pushed them, and I rarely did. The three of us were on a long car ride to Nana Florence’s house in Owen Sound – it must have been just before we stopped going there. They were always extra jittery when nearing Nana’s red brick house, especially during Christmastime when our stay was longer. Mom smoked even more during those long drives. Dad did too. He hadn’t quit at that point. I was clouded in smoke as I lay in the back seat, drugged with Gravol to stun the motion sickness I eventually outgrew. When did the elopement happen? Did you wear a white dress, Mom? Dad, did you wear a special suit? Didn’t somebody take a picture? Why was I hesitant to ask them these questions? I could feel the wall they’d built.

“Where did you elope again?” My voice was coated with sleep. They couldn’t say go play in your room. I had them trapped. I sat up.

They glanced at each other. “Cape Cod,” said Dad.

“Mom, you said Peggy’s Cove.”

She gave Dad a tight-eyed look. “I meant Cape Cod, honey. It’s easy to get them mixed up.”

Mom never made mistakes. I twisted the neck of my stuffed animal, Lambie, where I’d rubbed the fur away.

“What’s with all the goddamn questions? If you knew the answer, why ask?” said Dad.

I never got any further than that. Cindy and her stupid questions, her weird fixation on my parents’ wedding.

“You need to practise for the big day,” said Cindy. “I’m going to have a long train, a bouquet of yellow roses and a long veil like Mom’s.” She sidled beside me and hooked her arm through mine. I shimmied out of her hold and elbowed her. “Oww,” she said, dropping the pillowcase. “That hurt!”

“Put it back,” I said, stepping over the threshold into the hallway. “I’m getting Monopoly.”

When the rain finally stopped, we didn’t want to go swimming but wanted to be near the quarry, so we went out in the little battered rowboat. I sat in the middle and Cindy, the stern. She saw the far side of the quarry. I saw what we were leaving – the dock and the tall cottonwood trees, the cedar hedges lining our brown L-shaped bungalow, the surrounding lawn, cut weekly by Dad, and Mom’s begonias and impatiens. As I rowed further a sensation trickled through me, as if I were seeing outside myself, like a flying bird or a god watching.

What did Cindy see, facing the other way? Where the bush grew thick and jungle-like and the edge of the limestone was jagged, all that green, the water a mirror soaking it up, ripe like watermelon rind. The other side, where the birds and animals lived: osprey, fox, deer.

We listened for splashes. Fish jump! Then we turned to the source, the dissolving water rings. When we finally made it to the other side, we looked for the great blue heron.

“Shh,” I said. The bird did a good job of blending in, but when I looked closely, there she was, just like I’d told Cindy. Grey and blue and wonderful. Yellow beak and curved mesh of long grey feathers. Beady eyes and sticklike legs. She was wading on the underwater limestone ledges where I’d first sighted her, before Cindy’s arrival. I rested the oars and let the boat arrow in slowly toward her.

“See?” I whispered. “Told you we’d see her.”

We floated over the hazy green, the only motion the boat’s soft glide; our mouths were open and speechless. And then the heron’s long wings expanded, lifting her up and up, above our heads. We felt the wing-flaps of warm air.

“It’s afraid,” said Cindy.

“No, she’s not. She knows we won’t hurt her.” Her airborne limbs lacked any tension, the way my limbs did when I swam underwater, away from the air-troubled world.

“You don’t know that. And you don’t know it’s a she.”

“Do so,” I said. Though I couldn’t recall the picture in Mom’s bird book to prove my point, I had a knowing feeling.

After the heron had flown out of sight, I landed the boat on the jungle-side. We sat on one of the limestone ledges and fingered fossils I’d learned the names of in school. Snail-shaped ammonites and beetle-shaped trilobites. The question-mark curls of the nameless worms. We Brailled the language of stone.

“It’s like a cemetery,” Cindy said, breaking the silence. “Only the stone doesn’t mark a grave, it is the grave. Ew!” She wiped her finger on the belly of my green bathing suit.

She was being silly and I didn’t want to be silly. I wanted to keep touching the lost lives of the little. But she wouldn’t stop, so I told her about the drowned woman, a story I’d overheard my parents talking about. A young woman, an orphan, had lost her will to live. The water had called to her, a mirror she could slip into to disappear, as if returning to her mother. That’s not how my parents had told the story but that’s how I thought of it. The image of the woman’s water-cradled body. That same thrilling chill moved through me again as I told Cindy. I understood that pull.

“She tied a rope round her ankle, the other end to a rock.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” said Cindy. “You’re making that up.”

I pointed to the wedge of tree and bush that led to Windmill Point Road, the road at the end of our long gravel driveway. “She lived over there.”

“Alone?” said Cindy, trying to see through the greens.

I nodded.

“Who lives there now?”

I didn’t answer. She was trying to change the subject to shift the disturbing image, the rock-anchored body’s fall through dark watery depths.

“Her lungs would fill,” I said. “And the water would bloat her.”

Cindy giggled. “Sounded like you said boat her.”

“You think it’s funny? She must’ve been sad.”

“I don’t get it. Why would you want to?” She put her hand over the water’s skin and flicked the surface.

“Hey!” I said, splashing her back.

We got back in the boat and I rowed us home, directly over the deepest part of the quarry. It wasn’t the only spot you couldn’t see rock bottom, but somehow knowing it was there gave me a crisp, eerie feeling. We were quiet when we passed over it. We knew to respect it with silence.

“Look! A hand!” I couldn’t resist. I saw fear rise through my cousin’s face, punching through her brown eyes. And then her eyes welled up.

“That’s not funny,” she said and she turned away.

That night I couldn’t sleep. I watched Cindy in the twin bed beside me. Hers was the body I used to have when I was cute and small, and when her dimples popped from Dad’s attention it chiselled my gut. Tucked under the covers, I stared at the room’s dark and willed my body to ease and lighten, for the quarry inside me to calm again.

It was my first day without her. I sat alone on the dock bench, the water a mirror for the limestone to fall into. Postcard pretty but all I felt was this rock-bottom ache. Even though she was thinner, and Dad said she was a better diver, I missed my cousin. I needed to learn to be alone again. I decided to go out in the boat.

I rowed through the chilly wind to the other side of the quarry and our house grew smaller and smaller. It seemed fitting that I found the lifeless body of the heron, twisted in a question-mark curl, under the leaves of the overhanging branches. It moved to the gentle waves the oars made. One wing was outstretched like a carpet. No smell of decay, as if the heron had decided to play dead like Cindy and I did between the dock and the floating raft.

I didn’t think about the cause. I only wanted to fold the extended wing back in like an accordion or a fan, but I heard Cindy’s voice: it’s dead, it won’t know the difference. And then this cutting feeling came with words, leave it alone, row home. I dunked in the oars and rowed through the quiet. The view of the jungle-side grew smaller until it blurred into one long band.

Soon it was too cold to swim, but I wanted to be inside the quarry. Mom was too tired to watch me. I have to lie down now, dear. When Dad finally arrived home from another sales meeting, I asked him to sit on the dock. He agreed, but once we were there I knew from the glazed look on his face that his mind was elsewhere.

“Dad,” I said, blocking his line of vision. “Aren’t you watching?” I waved my arms.

“I’m watching.”

I dove in.

“Nice About-to-Die Dive,” he said as I climbed up the ladder.

“Thanks.” I slicked back my hair and readied myself for the next one.

“Nice Drowning Dive,” he said. His praise trickled through my dripping body. I wanted more.

“I’m going in again, Dad. Ready?”

“Ready.”

“Nice,” he said when I climbed back up.

This time I didn’t feel the trickle of praise running through me. With nobody to be nice against, his “nice” meant nothing.

It was the day before Christmas Eve and I was sitting in the family room on the curve of the chesterfield, watching a horse-drawn covered wagon trundle across the television screen, when the phone call in the kitchen reached its peak. Mom was talking to Aunt Doris. The Brants were coming to our house this Christmas holiday. I couldn’t wait.

“Maybe you’ll come to my funeral then,” Mom said into the telephone, her voice high-pitched, a tone foreign to my ears.

I shifted from my curled-up position, ready to jump.

Dad lunged into the kitchen from his office and grabbed the receiver. “Doris! That’s enough! How dare you make Rusty cry.” He slammed down the phone.

My funeral. After Mom said those words, I knew what was hidden inside that horse-drawn covered wagon – a closed coffin, and inside the coffin, my mother.

I felt strangely removed from the scene in the yellow kitchen, just as I felt strangely removed from the new wig on Mom’s head and her puffy cheeks. Mom was crying and she never cried. I’d been witness to this family fallout between Mom and Dad and Dad’s younger sister Doris, and I wished I hadn’t. I was in their line of vision but they weren’t looking at me. Dad’s arm around the slope of Mom’s shaking shoulders. Her tiny sobs. She was working hard to hold them in. Something she knew how to do, hold things in. But they didn’t see me watching them. It was as if I wasn’t there.

“What happened?” I said, stepping into the kitchen. “Aren’t they coming for Christmas?” My stomach knotted.

The snow had started up again and the evening wind was whipping it against the kitchen window, a chipping sound like chattering teeth.

“Fine,” Dad said. “We’ll have Christmas without them. Caitlin, you hear that?” He let go of Mom’s shoulders and looked out the window. “A little snow … some excuse. Storm? I’ll show them storm. She never worries when I’m driving, right, Russ? One-way road, I tell you. It’s always been that way. She can hurt me all she wants but not you.” He stared out at the white-flaking dark.

I was shocked. Christmas without my aunt and uncle, my cousins. The two older boys I wouldn’t miss, but Cindy? “Cindy’s not coming? What about our gifts?” No homemade dolls or hard-sucking sweets or hard-backed Nancy Drews. Nobody to show my presents to.

Didn’t they know Mom was sick? Though Dad said she was getting better. The drugs that made her hair fall out and rounded her face were good things, temporary side effects. Mom was getting better. That’s what Dad said.

I thought back to that day, in early October. The bungalow was quiet when I got home from school. Both cars parked in the carport, so the quiet didn’t make sense. I should be hearing Dad’s voice. He should be talking to Mom about his day. I looked out the kitchen window at the quarry. Whitecaps up and gone in an instant.

“Hello?”

No answer. I walked through the kitchen into the family room, and when I got there, I stopped.

There was Dad in the Windsor chair, hands on his forehead, leaning forward, and there was Mom, curled in her chesterfield nook, the ashtray heaped with pink-rimmed butts. Was it the Merck Manual lying there, was that my clue? The leather-bound book from her nursing school days, tucked in the curve of her legs?

“We have something to tell you,” Dad said, staring at the floor.

I clutched my binder to my chest. And then these words flew out of my mouth: “It’s cancer, isn’t it?”

He didn’t look up.

Mom turned to me. “I’m sorry,” she said, butting out her cigarette. “I didn’t want this to happen to you.”

It didn’t happen to me, Mom. It happened to you.

I watched the layers of smoke float through the room.

How could the Brant family not come?

Under the dock light, through the hurtling snow, the quarry waved metallic grey, the steel grey of machinery. No skin had formed yet, so snow absorbed into it, a seasoned cauldron of cold soup.

I didn’t want cold winter. I wanted it to be warm like summer when Cindy was here. The long months of waiting for her return would have no payoff now. Had Cindy heard the phone call from her end? Was she upset about us not being together for Christmas? A chill ran down my spine, an icy mouse.

I returned to the chesterfield to watch TV. The snow had stopped making that chipping sound, but the night wind howled.

Dad offered me his glass of milk, his nightly ritual to help him fall asleep. “Have some. It’ll help tonight.”

I didn’t want the milk, but the charged atmosphere remained, so I took a sip.

“Good girl,” he said, taking back the glass.

“Sleep well, honey,” said Mom. Her shoulders were calm but her voice held sadness in it. Outside the family room window, the shadowy tube of the bird feeder swung back and forth, the winter birds hidden in bushes and trees. “We’ll have our own family Christmas,” said Mom. “Just the three of us.”

Christmas morning I awoke to a quiet house. I picked up the box of worry dolls sitting on my bedside table, last year’s Christmas gift from Aunt Doris. “Just for you,” she’d said. When I lifted off the oval lid of the tiny bamboo box, six wiry dolls in bright colours were clumped inside it. “They’re called worry dolls,” said Aunt Doris. “All the way from Guatemala. For my little worrier.” She smiled.

I’d set out all six last night. I told each doll the same worries: I wish the Brant family was here for Christmas. I wish Mom’s cancer would go away. But then I realized, those weren’t worries, they were wishes.

I dropped the dolls back in the box and pushed down the lid. I felt the worries inside my stomach – expanding, contracting.

I thought Mom and Dad were still asleep when I got up, the house was so quiet, but they were sitting in the family room drinking their morning coffee. I walked through the layers of smoke and sat down on the chesterfield. “Can we open our presents now?”

They nodded.

We moved to the living room, beside the small twinkling tree, and opened up gifts. I got what I wanted – the new record Donny & Marie: Featuring Songs from Their Television Show. But no homemade dolls or homemade sweets or hard-backed Nancy Drews. Nobody to show my presents to.

The sky shone extra bright outside. Clear and blue, no hint of storm. Not even a breeze. The predicted snow hadn’t come, so a nervous winter driver like Aunt Doris would have been fine on the busy highway, taking her time. She’d have been fine driving Uncle Jim’s station wagon – his one arm in a sling from his squash accident, the two boys teasing their little brown-eyed sister in the back seat – but that phone call had piled a snow bank so high, nobody could pass through it.

The Pink-Shingled Cottage

Before my parents bought the house by the quarry we spent summer holidays in Southampton. The compact interior of the pink-shingled cottage smelled of Lake Huron water and Lake Huron sand plus the nearby cedar and pine trees. These outdoor scents mingled tightly with indoor scents: QT tanning lotion, The Dry Look hairspray, Old Spice, Benson & Hedges, Chanel No 5.

Everyday Mom played the sport she loved at the nearby tennis club. With a backhand as strong as her forehand, she could whack any oncoming ball. Singles. Doubles. She played to win, dressed in her home-made Simplicity-pattern tennis dresses. Spectators loved to watch her skillful playing. But of all the eyes watching, none shone like those of her biggest fan.

Rusty, always my champion.

These were the words Dad had engraved on a silver ID bracelet after she lost a close match. She didn’t like to be defeated. Dad thought the gift would cheer her up, and it did.

One day she left the bracelet sitting by the cottage kitchen sink. I fastened it to my wrist but it rolled right off. You’ll never be a champion, said the voice in my head.

There was a rich American who admired my mother’s talent for tennis, and he often asked her to play. Mom always beat Mr. Davy, but he worked hard to narrow the gap. His tanned face trickled with sideburns and his silver hair, slick with dark streaks. He and his non-playing wife would drop by the pink-shingled cottage after round robins. Mrs. Davy always wore her hair pulled back in an elegant bun (Mom called it a chignon). Her complexion was clear and tanned. It didn’t freckle out of control like Mom’s summer face.

Rye and ginger. Rum and Coke. I helped Dad bartend. One evening he was telling a joke in his fake Québécois accent, the ladies listening intently from across the kitchen table. He was getting closer to the punchline. I could hear the rising rhythm. Mr. Davy looked bored standing by the screen door.

“Here you go,” I said, handing him his rum and Coke.

The ice tinkled when he shook the glass. “You don’t play, do you?” he said. “But you’ve got a racquet.”

I nodded.

He looked me up and down. “Your mother is an amazing player. I’d be surprised if you didn’t have some of that in you.” He took a sip and watched me. His Adam’s apple flickered up.

It would be rude to turn away. He smacked his lips. My signal to go?

“Bet you see three rolls of fat when you’re sitting in the tub,” he whispered. He stared at my stomach, where the worry lived. “Am I right, Caitlin?”

“Three,” I said, not knowing what else to say.

“Hey,” said Dad. His voice rose above the ladies’ laughter. “Where’s my little bartender?”

“Go,” said Mr. Davy, winking.

That night when Mom came into my room to kiss me goodnight, I asked her if she thought I was fat.

“You’re not fat.”

I pushed back the blanket and lifted my gingham nightie, grabbed a chunk of flesh. “What’s this then?” I said, eyeing her.

She smiled. “It’s puppy fat, honey. I had it too when I was ten. Not to worry, you’ll grow out of it.”

I thought of the silver ID bracelet that didn’t fit. I thought of the tennis balls I couldn’t hit.

Red Bars

I sat in the back seat of Mom’s Malibu convertible, fingering the seat-belt buckle, half-listening to Mom and her new friend Eleanor, a long-time member of the church we’d started going to after our first Christmas at the quarry. I was going for my Bronze Medallion and I needed a new bathing suit. My green Speedo left indents on my shoulders. Red bars.

It was the beginning of March break, and we were taking the back route, the safe route, to the mall, instead of the highway, so Mom wouldn’t make those sharp intakes of breath (no transport trucks to pass us). Mom, like Aunt Doris, disliked highway driving. But we didn’t talk about Aunt Doris like we didn’t talk about Cindy and her time at the quarry. Despite having avoided the highway, Mom seemed high-strung, her mouth tight as she nodded in response to Eleanor’s yammering.

“Did you see when she pushed up her sleeve? She must’ve forgotten they were there, until she saw me looking from down the pew.” Eleanor shook her head. “I don’t know how Carol can stay with him.”

“It’s not so easy to leave a husband,” said Mom.

“Come on, if Don started doing that? Henry, if he so much as gives me the evil eye, I’m at him with my broom.” Eleanor laughed.

Mom, squeezing the wheel hard with both hands, was oblivious to my watching her. I stared at the squiggles congregating on her nose, red like her wig. She never found her original shade, so a deeper auburn had to do. It fell flat on her head like a bathing cap. Not like her real hair, those subtle waves. So different from Eleanor’s coarse black spikes.

That first time she went to the hospital, no one told me she had cancer. “Your mother’s going to have a woman’s operation.” I wore barrettes then, and I remember touching the cold metal after Dad said those words. The barrettes had red birds painted on them. If you looked close enough, you could see music notes seeping from their beaks.

Woman’s operation.

We lived in Grimsby. No quarry yet. Our flat-roofed house was built next to the beauty of the Niagara Escarpment. Upside-Down House. Bedrooms downstairs. Kitchen and living room up. “Weird,” said the kids I played with. “Your house is weird. Your own bathroom?” They said it like I had a disease. I stopped inviting them over.

I should’ve known better about the birds. But once they were clipped in, I forgot about them, like the way you forget you’ve got ice cream on your chin, until someone points.

We were standing in line, in the school hallway. The scent of lemon drifted from the janitor’s floor polisher moving down the hall. I was thinking about the “woman’s operation.” What did that mean? Would I need one when I grew up? Why hadn’t Mom told me?

“You’re in my way,” said Gail, the classmate standing behind me.

We’d been put into alphabetical order. Otherwise, I’d never stand in front of Gail. She nudged my waist with the cut of her elbow. I turned toward her, my body’s response.

“Birds,” she said, her voice, a sharp tweak. “Little birdies singing music notes. Isn’t that cute?” When she snickered, her shoulders hunched. She turned to the girl behind her. “See how red she went this time?” Gail whispered. “Check her out.”

I could never tell the little birds apart. Chickadees and juncos were both small and bouncy and mostly grey. Mom said I needed to pay closer attention, to spend more time seeing what was there, right in front of me. Her favourite was the cardinal. Not the male with his bright red, showy feathers but the subdued female, her feathers a warm, red-tinged brown.

Sometimes while playing outside, I found a feather lying on the ground. I would pick it up and bring it back to Mom. She collected them in a vase by the windowsill. Blooms of feathery light.

The line began to move. Mrs. Styles, our music teacher, welcomed us at the door to her classroom. “Fiddler on the Roof! ‘Sunrise, Sunset’! Hope you know your lyrics!”

I headed to the back and opened Songbook Five, held it like a wall.