9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Railway Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

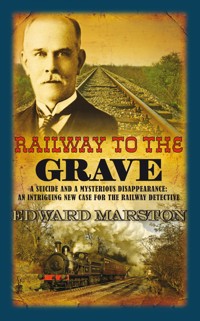

Tragedy strikes close to the Detective Department when an old friend of Superintendent Tallis walks to meet a speeding train head on. The suicide, prompted by the disappearance of the man's wife, has shocked the local community and leaves plenty for Inspector Robert Colbeck, the Railway Detective, to uncover. Whispers and rumours abound but did the dead man, Captain Randall, really take his own life in repentance for some harm he did his wife?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Railway to the Grave

EDWARD MARSTON

Allison & Busby Limited

13 Charlotte Mews

London W1T 4EJ

www.allisonandbusby.com

Copyright © 2010 by EDWARD MARSTON

First published in hardback by Allison & Busby Ltd in 2010.

This ebook edition first published in 2010.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Digital conversion by Pindar NZ.

All characters and events in this publication other than those clearly in the public domain are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any format other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7490-0925-0

EDWARD MARSTON was born and brought up in South Wales. A full-time writer for over thirty years, he has worked in radio, film, television and the theatre and is a former chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association. Prolific and highly successful, he is equally at home writing children’s books or literary criticism, plays or biographies. Railway to the Grave is the latest book in the series featuring Inspector Robert Colbeck and Sergeant Victor Leeming, set in the 1850s.

www.edwardmarston.com

Available from

ALLISON & BUSBY

The Inspector Robert Colbeck series

The Railway Detective

The Excursion Train

The Railway Viaduct

The Iron Horse

Murder on the Brighton Express

The Silver Locomotive Mystery

Railway to the Grave

The Christopher Redmayne series

The King’s Evil

The Amorous Nightingale

The Repentant Rake

The Frost Fair

The Parliament House

The Painted Lady

The Captain Rawson series

Soldier of Fortune

Drums of War

Fire and Sword

In loving memory of

Raymond Allen

uncle, friend and engine driver

CHAPTER ONE

1855

Colonel Aubrey Tarleton led an orderly existence. Born into a military family and subject to the dictates of a martinet father, he’d been educated at a public school that prided itself on its strict regime. When he joined the army, therefore, he was already accustomed to a life within prescribed limits. He felt supremely comfortable in uniform and, as succeeding promotions came, he gloried in his position. His father had never risen above the rank of major. To acquire a colonelcy and thereby better the man who’d sired him was, to Tarleton, a source of intense satisfaction. He carried that satisfaction into his retirement, finding, in civilian life, the deference to which he felt entitled.

‘Is that all you want, Colonel?’ asked his housekeeper, softly.

‘That is all, Mrs Withers,’ he replied.

‘As a rule, you have such a hearty breakfast.’

‘I don’t feel hungry this morning.’

‘Shall I make you some more coffee?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Very good, sir.’

With a respectful nod, Mrs Withers backed out of the dining room. She was a handsome woman of middle years with an ample frame held firmly in place beneath her dress by steadfast stays. Retreating to the kitchen, she waited until she heard Tarleton ascending the staircase, then she snapped her fingers at the girl who was cleaning the knives with emery powder. Subdued in the presence of her employer, the housekeeper now became peremptory.

‘Clear the table,’ she ordered.

‘Yes, Mrs Withers,’ said Lottie Pearl.

‘And be quick about it.’

‘Did the colonel eat anything today?’

‘That’s none of your business, girl.’

‘I was only wondering.’

‘You’re not paid to wonder.’

‘No, Mrs Withers.’

‘Now do as you’re told.’

Lottie scurried out with a tray in her hands. She was a scrawny girl of sixteen and, as maid-of-all-work, was a relative newcomer to the house. In awe of Colonel Tarleton, she was frightened of the stern housekeeper and of her curt reproaches. Creeping tentatively into the dining room, she looked at the untouched eggs and the half-eaten piece of bread on the plate. Only a few sips had been taken from the cup of coffee. The sound of heavy footsteps in the bedroom above made her glance warily up.

Tarleton was on the move, crossing to open the wardrobe in order to examine its contents before walking to the window to look up at the sky. When he’d taken his usual morning walk with the dog before breakfast, there’d been more than a hint of rain in the clouds but they seemed to have drifted benignly away, allowing the sun to come into view. On such an important day, he was determined to dress well. After removing the well-worn corduroy suit he kept for his rambles through the countryside, he changed his shirt and put on his best trousers, waistcoat and frock coat. Shining black shoes, a fob watch and a cravat completed the outfit. Tarleton studied himself with care in the cheval mirror, making a few adjustments to his apparel then brushing back some strands of thinning white hair.

Taking a deep breath, he crossed to the door that led to the adjoining room and tapped politely on it. Though there was no response from within, he opened the door and gazed wistfully around. Everything in the room was a cherished keepsake. His eyes took in the paintings, the vases, the plants, the ornaments, the jewellery box, the furniture, the Persian carpet and the more functional objects before lingering on the double bed. On the wall above it was a beautiful Dutch tapestry that set off a surge of fond memories and he permitted himself a moment to savour them. After bestowing a wan smile on the room, he withdrew again and closed the door gently behind him as if not wishing to disturb its occupant. Then he collected his wallet, his spectacles and a folded sheet of paper. The last thing he picked up was a large safety pin.

Mrs Withers was waiting for him in the hallway, holding his top hat. As he took it from her, she indicated the letter on the table.

‘The postman came while you were upstairs, Colonel,’ she said.

‘I’ve no time to read the mail now, Mrs Withers.’

‘But there might be news.’ She quailed slightly as he turned to stare at her with a mingled anger and pain. Writhing under his glare, she gestured apologetically. ‘Forgive me, sir. I spoke out of turn. You know best, of course.’

‘Of course,’ he emphasised.

‘Do you have any orders for me?’

‘Remember to feed the dog.’

‘I will, Colonel.’

‘Goodbye, Mrs Withers.’

‘What train will you be catching back from Doncaster?’

‘Goodbye.’

It was a brusque departure. He didn’t even wait for her to use the clothes brush on his coat. Putting on his hat and picking up his walking stick, he let himself out of the house and strode off down the drive. Face clouded with concern, the housekeeper watched him through the glass-panelled door but Tarleton did not look back. His tall, erect, still soldierly figure marched briskly away towards the main gate as if on parade before royalty.

South Otterington was a pleasant, scattered village on the east side of the River Wiske, large enough to have a railway station, three public houses, two blacksmiths and a cluster of shops, yet small enough for each inhabitant to know everyone else in the community. Colonel Tarleton was a familiar sight there, a member of the gentry held in high esteem as much for his heroic feats in the army as for his social position. When he’d walked the mile or so from his home, he entered the main street to be greeted by a series of ingratiating smiles, polite nods and obsequious salutes. He acknowledged them all with a lordly wave of his walking stick. Nan Pearl, returning from the butcher with scraps for her mangy cat, all but curtsied to him, desperately hoping for a brief word of praise for her daughter, Lottie, now in service at the Tarleton household. Instead she got an almost imperceptible nod. Mrs Skelton, the rector’s wife, on the other hand, merited a tilt of his top hat and a cold smile that flitted across his gaunt face.

Though he seemed to be heading for the railway station, he walked past it and continued on until he’d left the village behind him and was out into open countryside. Fields of wheat and barley lay all round him. Sheep were grazing contentedly on a hillside. There was fitful birdsong but it only increased the extraordinary sense of peace and tranquillity. Tarleton had always loved his native Yorkshire and never tired of roaming the North Riding on foot. This time, however, he took no pleasure from the surroundings. His mind was concentrated on a single goal and nothing could distract him from it.

He kept on until he judged himself to be midway between the village and Thirsk to its south. At that point, he clambered over a gate and picked his way across a wheat field until it dipped down towards the railway line. He was still spry enough to climb over the dry-stone wall without difficulty, straightening his hat when he reached the track then slipping a hand inside his pocket. He took out the sheet of paper and used the safety pin to secure it to his coat like a medal. A glance at his watch told him that he had timed his arrival perfectly. Dropping the watch back into his waistcoat pocket, Tarleton took a deep breath and inflated his chest.

He was ready. Keeping between the rails, he walked over the sleepers with a measured tread. He was quite untroubled by fear. When he heard the distant noise of an approaching train, he sighed with joy. His ordeal would soon be over.

Halfway between Thirsk and South Otterington, the train was travelling at full speed. Standing on the footplate, the driver and the fireman were chatting happily together. The journey had passed without incident and they could congratulate themselves on their punctuality at each stage. When they came round a long bend, however, their good humour vanished. The driver saw him first, an elderly gentleman walking uncaringly towards them on the track as if out on a morning stroll. The fireman could not believe his eyes. Cupping his hands, he yelled a warning at the top of his voice but it was drowned out by the frenzied panting of the locomotive and the ear-splitting rattle of the train. Even the shrill blast of the whistle did not deter the oncoming walker. His gait remained as steady as ever.

Shutting off steam, the driver applied the brakes but there was no hope of stopping in such a short distance. All that they could do was to watch in horror as he strode deliberately towards the hurtling train. They had hit animals before when they’d strayed on the line but this was a very different matter. Here was a flesh and blood human being – a man of substance, by the look of it – advancing towards them with an air of challenge about him. It shook them. At the last moment, both driver and fireman turned away. The impact came and the train surged on, carriage after remorseless carriage rolling over the mangled, blood-covered corpse on the track.

Shocked by what had happened, the fireman emptied the contents of his stomach over the footplate. The driver, meanwhile, feeling somehow guilty at the hideous death, closed his eyes and offered up a prayer for the soul of the victim. When the squealing train finally ground to a halt amid a shower of sparks, the driver was the first to jump down from the locomotive and run back up the track. He kept going until he reached the lifeless body, buffeted into oblivion and spread untidily across the sleepers. The face had been smashed to a pulp and the walking stick split into a dozen pieces. What caught the driver’s attention, however, were not the gaping wounds and the misshapen limbs. It was a piece of paper, pinned to the man’s coat and flapping about in the breeze.

He bent down to read Colonel Tarleton’s last request.

‘Whoever finds me, notify Superintendent Tallis of the Detective Department at Scotland Yard.’

CHAPTER TWO

Detective Inspector Robert Colbeck liked to make an early start to the working day but the cab ride to Scotland Yard showed him that London had already been wide awake for hours. The pavements were crowded, the streets thick with traffic and the capital throbbing with its distinctive hullaballoo. Glad to reach the restorative calm of his office, he was unable to enjoy it for even a moment. A constable told him to report to Superintendent Tallis immediately. There was a note of urgency in the man’s voice. Colbeck obeyed the summons at once. After knocking on Tallis’s door, he let himself into the room even though he was given no permission to do so. He soon saw why.

Wreathed in cigar smoke, the superintendent was leaning forward across his desk, supporting himself on his elbows and staring at some invisible object in the middle distance. Beside him was a bottle of brandy and an empty glass. Colbeck knew that something serious had happened. Consuming alcohol while on duty was anathema to Edward Tallis. He’d dismissed several men from the Metropolitan Police Force for doing just that. Strong drink, he argued, only impaired the mind. If he was ever under pressure, he would instead reach for a cigar. The one between his lips was the third that morning. The blackened vestiges of its two predecessors lay in the ashtray. Tallis was in pain.

‘Good morning, sir,’ said Colbeck.

The superintendent looked up. ‘What?’

‘You sent for me, I believe.’

‘Is that you, Inspector?’

‘What seems to be the problem?’

Tallis needed a moment to compose himself. Taking a last puff on his cigar, he stubbed it out in the ashtray and waved a hand to disperse some of the fug. Then he pulled himself up in his chair. Noticing the bottle, he swept it off the desk and put it away in a drawer. He was plainly discomfited at being caught with the brandy and tried to cover his embarrassment with a nervous laugh. Colbeck waited patiently. Now that he could see his superior more clearly, he noticed something that he would not have believed possible. Tallis’s eyes were moist and red-rimmed. He’d been crying.

‘Are you unwell, Superintendent?’ he asked, solicitously.

‘Of course not, man,’ snapped Tallis.

‘Has something upset you?’

The explosion was instantaneous. ‘The devil it has! I’m in a state of permanent upset. How can I police a city the size of London with a handful of officers and a woefully inadequate budget? How can I make the streets safe for decent people when I lack the means to do so? Upset? I’m positively pulsing with rage, Inspector. I’m appalled by the huge volume of crime and by the apparent indifference of this lily-livered government to the dread consequences that it produces. In addition to that…’

It was vintage Tallis. He rumbled on for a few minutes, turning the handle of his mental barrel organ so that his trenchant opinions were churned out like so many jangling harmonies. It was his way of establishing his authority and of trying to draw a veil over the signs of weakness that Colbeck had observed. The inspector had heard it all before many times but he was courteous enough to pretend that he was listening to new-minted judgements based on sound wisdom. He nodded earnestly in agreement, watching the real Edward Tallis take shape again before him. When he’d regained his full confidence, the superintendent extracted a letter from his pocket and handed it over. It took Colbeck only seconds to read the emotive message.

‘Goodbye, dear friend. Though her body has not yet been found, I know in my heart that she is dead and have neither the strength nor the will to carry on without her. I go to join her in heaven.’

Colbeck noticed the signature – Aubrey Tarleton.

‘Is the gentleman a relation of yours, sir?’ he asked.

‘We were comrades-in-arms,’ replied Tallis, proudly. ‘Colonel Tarleton was an exemplary soldier and a treasured friend.’

‘I take it that he’s referring to his wife.’

‘They were very close.’

‘When did the letter arrive?’

‘Yesterday morning,’ said Tallis, taking it from him and reading it once more with a mixture of sadness and disbelief.

‘Then we may still be in time to prevent anything untoward happening,’ suggested Colbeck. ‘I see from his address that he lives in Yorkshire. Trains run regularly from King’s Cross. Would you like me to catch the next one to see if I can reach your friend before he does anything precipitous?’

‘It’s too late for that, Inspector.’

‘Oh?’

‘This telegraph was on my desk when I arrived.’ He indicated the piece of paper and Colbeck picked it up. ‘As you see, it tells of the death of a man on the railway line not far from Thirsk. A note was pinned to his coat, saying that I should be contacted.’

‘Yet no name of the man is given,’ said Colbeck, studying it. ‘The victim may be someone else altogether.’

‘It’s too big a coincidence.’

‘I disagree, sir. Colonel Tarleton was an army man, was he not?’

‘To the hilt – he came from a military family.’

‘Then he probably has some firearms in his possession.’

‘He has quite a collection,’ recalled Tallis. ‘Apart from various shotguns, he has an exquisite pair of duelling pistols.’

‘Isn’t that a more likely way for him to end his life? If, that is, he’s actually done so, and we’ve no clear proof of that. A bullet in the brain is a much quicker and cleaner way to commit suicide than by means of a railway.’

Tallis snatched back the telegraph. ‘It’s him, I tell you. And I want to get to the bottom of this.’

‘Sergeant Leeming and I can be on a train within the hour.’

‘I know, Inspector, and I will accompany you.’

‘Is that necessary?’

‘I owe it to Aubrey – to Colonel Tarleton. There has to be an explanation for this tragedy and it must lie in the death of his wife.’

‘But that’s only conjectural,’ Colbeck reminded him. ‘The letter says that she’s disappeared but no evidence is given of her demise. That’s an assumption made by the colonel. He could be mistaken.’

‘Nonsense!’ snarled Tallis.

‘There are other possibilities, sir.’

‘Such as?’

‘Well,’ said Colbeck, meeting the blazing eyes without flinching, ‘the lady might have been injured while out walking and unable to get back home. She might even have been abducted.’

‘Then a ransom note would have been received. Clearly, it was not, so we may discount that hypothesis. Only one possibility therefore remains – Miriam Tarleton has been murdered.’

‘With respect, Superintendent, you are jumping to conclusions. Even if we suppose that Mrs Tarleton is dead, it doesn’t follow that she must have been killed. Her death might have been accidental or even as a result of suicide.’

‘She’d have no call to take her own life.’

‘Can you be sure of that, sir?’

‘Yes, Inspector – it’s inconceivable.’

‘You know the lady better than I do,’ conceded Colbeck. ‘Given your knowledge of the marriage, is it also inconceivable that Mrs Tarleton is still alive and that she’s simply left her husband?’

Tallis leapt to his feet. ‘That’s a monstrous allegation!’ he yelled. ‘Colonel Tarleton and his wife were inseparable. What you suggest is an insult to their memory.’

‘It was not intended to be.’

‘Then waste no more of my time with these futile arguments. You read the letter. It’s a plea for my help and I intend to give it.’

‘Sergeant Leeming and I will be at your side, sir. If a crime has indeed been committed, we’ll not rest until it’s solved.’ Colbeck crossed to the door then paused. ‘I take it that you’ve visited Colonel Tarleton at his home?’

‘Yes, I have.’

‘How is he regarded in the area?’

‘With the greatest respect,’ said Tallis. ‘Apart from being a magistrate, he holds a number of other public offices. His death will be a terrible blow to the whole community.’

Lottie Pearl was stunned. The news of her employer’s gruesome death had left her speechless. She could not begin to comprehend how it had come about. Nothing in the colonel’s manner had given the slightest indication of what he had in mind. On the previous morning, he’d gone through his unvarying routine, rising early and taking the dog for a walk before breakfast. He’d eaten very little food but loss of appetite did not necessarily equate with suicidal tendencies. Lottie was in despair. Within weeks of her securing a coveted place there, she’d seen the mistress of the house vanish into thin air and the master go to his death on a railway line. Her prospects were decidedly bleak. When she finally recovered enough from the shock to be able to focus on the future, one question dominated. What would happen to her?

‘Lottie!’ called the housekeeper.

‘Yes, Mrs Withers?’

‘Come in here, girl.’

‘I’m coming, Mrs Withers.’

Lottie abandoned the crockery she’d been washing in the kitchen and dried her hands on her apron as she made her way to the drawing room. As soon as she entered, she came to a sudden halt and blinked in surprise. Seated in a chair beside the fireplace, Margery Withers was wearing a faded but still serviceable black dress and looked more like a grieving widow than a domestic servant. She used a handkerchief to stem her tears, then appraised Lottie.

‘You should be in mourning wear,’ she chided.

‘Should I, Mrs Withers?’

‘Do you have a black dress?’

‘No, I don’t,’ said Lottie, self-consciously.

‘Does your mother have one?’

‘Oh, yes, she does. She dyed an old dress black when Grandpa passed away.’

‘Then you must borrow it from her.’

‘What will I tell my mother?’

‘You must wear it out of respect. She’ll understand.’

‘That’s not what I mean, Mrs Withers,’ said Lottie, uneasily. ‘What am I to say to my mother about me?’

The housekeeper was puzzled. ‘About you?’

‘Yes, what’s to become of me now?’

‘Good heavens, girl!’ exclaimed the older woman in disgust. ‘How can you possibly think of yourself at a time like this? The colonel’s body is barely cold and all you can do is to flaunt your selfishness. Don’t you care what happened yesterday?’

‘Yes, Mrs Withers.’

‘Don’t you realise what the implications are?’

‘I’m not sure what you mean,’ said Lottie, regretting her folly in asking about her future. ‘All I know is that I was so hurt by the news about the colonel. He was such a decent man. I cried all night, I swear I did. And, yes, I will get that black dress. Colonel Tarleton ought to be mourned in his own home.’

Her gaze shifted to the portrait above the mantelpiece. Tarleton and his wife were seated on a rustic bench in their garden with the dog curled up at their feet. It was a summer’s day with everything in full bloom. The artist had caught the strong sense of togetherness between the couple, of two people quietly delighted with each other even after so many years. Lottie winced as she saw the smile on Miriam Tarleton’s face.

‘This will be the death of her,’ she murmured.

‘Speak up, girl.

‘I was thinking about the mistress. If ever she does come back to us – and I pray daily for her return – Mrs Tarleton will be upset beyond bearing when she learns about the colonel.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ said Mrs Withers, rising to her feet and looking at the portrait. ‘There’s no earthly chance of her coming back.’

‘You never know.’

‘Oh, yes, I do.’

The housekeeper spoke with such confidence that Lottie was taken aback. Until that moment, Mrs Withers had always nursed the hope of a miraculous return or, at least, had given the impression of doing so. There was a whiff of finality about her comment now. Hope was an illusion. Husband and wife were both dead. The realisation sent a cold shiver down Lottie’s spine.

‘We must prepare the guest bedrooms,’ continued Mrs Withers. ‘Word has been sent to the children so they will soon be on their way here. The house must be ready for them. Everything depends on their wishes. If one of them decides to move in here then there may be a place for you in due course, but only,’ she added, pointedly, ‘if I recommend you. So until we know what the future holds, I urge you to get on with your chores and forget about your own petty needs. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, Mrs Withers,’ said Lottie, recognising a dire warning when she heard one. ‘I do.’

Victor Leeming’s dejection sprang from three principal causes. He disliked train travel, he hated spending nights away from his wife and family, and he was intimidated by the proximity of Edward Tallis. The village of South Otterington sounded as if it was in the back of beyond, obliging the sergeant to spend hours of misery on the Great Northern Railway. From what he’d gathered, he might be away from home for days on end and his loved ones would be replaced by the spiky superintendent. It was a daunting prospect. All that he could do was to grit his teeth and curse inwardly.

Colbeck sympathised with him. Leeming was a man of action, never happier than when struggling with someone who resisted arrest or when diving into the Thames – as he’d done on two occasions – to save someone from drowning. Being trapped in the confines of a railway carriage, albeit in first class, was agony for him. Colbeck, by contrast, had found his natural milieu in the railway system. He took pleasure from each journey, enjoying the scenery and relishing the speed with which a train could take him such large distances. He tried to cheer up his sergeant with light conversation but his attempts were in vain. For his part, Tallis went off to sleep, snoring in unison with the clicking of the wheels yet still somehow managing to exude menace. Leeming spent most of the time in a hurt silence.

When they reached York ahead of schedule, there was a delay before departure. Tallis was one of the passengers who took advantage of the opportunity to visit the station’s toilets.

‘That’s a relief,’ said Leeming when they were alone. ‘I’ve never spent this long sitting so close to him. He frightens me.’

‘You should have overcome your fears by now,’ said Colbeck. ‘The superintendent poses no threat to you, Victor. He’s racked by grief. Colonel Tarleton was a very dear friend.’

‘I didn’t know that Mr Tallis had any friends.’

‘Neither did I. He’s always seemed such a lone wolf.’

‘Why did he never marry?’

‘We don’t know that he didn’t. In view of his deep distrust of the opposite sex, I agree that it’s highly unlikely, but even he must have felt the rising of the sap as a young man.’

‘He never was a young man,’ said Leeming, bitterly. ‘In fact, I don’t believe he came into this world by any normal means. He was hewn from solid rock.’

‘You wouldn’t have thought that if you’d seen him earlier. Solid rock is incapable of emotion yet Superintendent Tallis was profoundly moved today. We’ve been unkind to him, Victor. There is a heart beneath that granite exterior, after all.’

‘I refuse to believe it. But talking of marriage,’ he went on, glancing through the window to make sure that nobody was coming, ‘have you told him about your own plans?’

‘Not yet,’ confessed Colbeck.

‘Why not?’

‘I haven’t found the right moment.’

‘But it’s been weeks now.’

‘I’ve been waiting to catch him in the right mood.’

‘Then you’ll wait until Doomsday, sir. He’s never in the right mood. He’s either angry or very angry or something far worse. I tell you, I’d hate to be in your position.’

‘The appropriate time will arrive one day, Victor.’

It was during a previous investigation that Colbeck had become engaged to Madeleine Andrews, proposing to her in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter and buying her a ring there and then to seal their bond. While the betrothal had been formally announced in the newspapers, Tallis had not seen it. All that he ever read were court reports and articles relating to the latest crimes. Colbeck was biding his time until he could break the news gently. He knew that it would not be well received.

‘He never stops blaming me for getting married,’ complained Leeming. ‘He says that I’d be a far better detective if I’d stayed single.’

‘That’s not true at all. Marriage was the making of you.’

‘It’s having a happy home life that keeps me sane.’

‘I envy you, Victor.’

‘Have you set a date yet, sir?’

‘Oh, it won’t be for some time yet, I’m afraid.’

Colbeck was about to explain why when he saw Tallis coming along the platform towards them. Grim-faced and bristling with fury, the superintendent was waving a newspaper in the air. When he got into the carriage, he slammed the door behind him.

‘Have you seen this?’ he demanded.

‘What is it, sir?’ asked Leeming.

‘It’s a report about Colonel Tarleton’s death in the local newspaper,’ said Tallis, slumping into his seat, ‘and it makes the most dreadful insinuations about him. According to this, there are strong rumours that he committed suicide because he felt guilty over the disappearance of his wife. It more or less implies that he was responsible for her death. I’ve never heard anything so malicious in my entire life. The man who wrote this should be horsewhipped.’

‘Does he offer any evidence for the claim?’ wondered Colbeck.

‘Not a scrap – well, see for yourself.’ He thrust the newspaper at Colbeck and remained on the verge of apoplexy. ‘This puts a wholly new complexion on our visit to the North Riding. The colonel has not only lost his life. He’s in danger of losing his impeccable reputation as well. He must be vindicated, do you hear?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Leeming, dutifully.

‘Slander is a vicious crime. We must root out those with poisonous tongues and bring them before the courts. By Jove!’ he added, seething. ‘We’re going to tear that damned village apart until we find the truth. Mark my words – someone will suffer for this.’

CHAPTER THREE

For most of its existence, South Otterington had been largely untouched by scandal. It was a relatively safe and uneventful place in which to live. Petty theft and being drunk and disorderly were the only crimes to disturb the even tenor of the village and they were occasional rather than permanent features of its little world. The disappearance of Miriam Tarleton from ‘the big house’ was a different matter altogether. It concentrated the minds of all the inhabitants and set alight a roaring bonfire of speculation. The grotesque suicide of the colonel only served to add fuel to the flames. There was a veritable inferno of gossip and conjecture. Precious little of it, however, seemed to favour the dead man.

By the time that the detectives arrived, rumour was starting to harden into accepted fact. Alighting from the train, the first person they sought out was the stationmaster, Silas Ellerby, a short, slight, middle-aged man with protruding eyes and florid cheeks. When the visitors introduced themselves, he was suitably impressed.

‘You’ve come all the way from London?’ he asked.

‘There are personal as well as professional reasons why I want a full investigation,’ explained Tallis. ‘The colonel and I were friends. We served together in India.’

‘I thought you had the look of an army man, sir.’

‘Who’s been put in charge of this business?’

‘That would be Sergeant Hepworth of the railway police.’

‘I’ll need to speak to him.’

‘He lives here in the village.’

‘Mr Ellerby,’ said Colbeck, taking over, ‘the colonel’s death is clearly linked to the disappearance of his wife. How long has Mrs Tarleton been missing?’

‘It must be all of two weeks now,’ replied Ellerby.

‘Was an extensive search undertaken?’

‘Yes, the colonel had dozens of people out looking for her.’

‘He’d have led the search himself,’ said Tallis.

‘He did, sir – day after day, from dawn till dusk.’

‘Were no clues found?’

‘Never a one – it was baffling.’

‘Let’s go back to the events of yesterday,’ suggested Colbeck. ‘Where exactly did the suicide take place?’

‘It was roughly midway between here and Thirsk.’

‘That’s south of here, then.’

‘Correct, sir.’

‘According to the superintendent, the colonel’s house lies due north. If he wanted to throw himself in front of a train, he could have done so without coming through the village at all.’

‘Sergeant Hepworth had the answer to that.’

‘I’d be interested to hear it.’

‘The line to Northallerton is fairly straight. The driver would have had a better chance of seeing someone long before the train reached him. He might even have been able to stop in time. The colonel chose his spot with care,’ Ellerby went on. ‘He picked the sharpest bend so that he wouldn’t be spotted until it was far too late. Hal Woodman said there wasn’t a hope of missing him.’

‘Was Mr Woodman the driver?’

‘Yes, Inspector, and it turned him to a jelly. When the train pulled in here, Hal could hardly speak and his fireman was in an even worse state. I’ll wager they’re both off work today.’

‘You talk as if you know them, Mr Ellerby.’

‘I should do. I’ve had many a pint with Hal Woodman and Seth Roseby over the years. It wasn’t an express between London and Edinburgh, you see. It was a local train that runs between York and Darlington.’

‘Where does Mr Woodman live?’

‘He’s just over four miles away in Northallerton.’

‘Sergeant,’ said Colbeck, turning to him. ‘I think that you should pay him a visit. Take the next train.’

‘But we’ve only just got here,’ protested Leeming.

‘It’s important to have a clearer idea of what actually happened.’

‘I can give you Hal’s address,’ volunteered Ellerby.

‘Then it’s settled,’ said Tallis, taking control. ‘Leave your bag with us and catch the next train to Northallerton.’

‘Yes, Superintendent,’ said Leeming with a grimace. ‘Where will I find you when I come back?’

‘They have two rooms at the Black Bull,’ said Ellerby, pointing a finger, ‘and George Jolly lets out a room at the rear of the Swan, if you don’t mind cobwebs and beetles.’

‘That one will do for you, Sergeant,’ decided Tallis. ‘We’ll probably be at the Black Bull. Meet us there. When we’ve booked some rooms, we’ll be going out to the colonel’s house. The first person I want to speak to is Mrs Withers.’

Margery Withers let herself in and crossed to the window. It was the biggest and most comfortable bedroom in the house, commanding a fine view of the garden and of the fields beyond. She spent a few minutes gazing down at the well-tended lawns and borders, noting the rustic bench on which her employers had once posed for a portrait and the ornamental pond with its darting fish. She was torn between anguish and elation, grief-stricken at the colonel’s suicide yet strangely excited by the fact that she – however briefly – was now the mistress of the house.

After looking around the room with a proprietorial smile, she did something that she had always wanted to do. She sat in front of the dressing table and opened the jewellery box in front of her. Out came the pearl necklace she’d seen so many times around the throat of Miriam Tarleton. The very feel of it sent a thrill through her and she couldn’t resist putting it on and admiring the effect in the mirror. Next came a pair of matching earrings which she held up to her lobes, then she took out a diamond bracelet and slipped it on her wrist. It had cost more than her wages for a year and she stroked it jealously.

On and on she went, working her way through the contents of the box and luxuriating in temporary ownership. Mrs Withers was so caught up in her fantasy that she didn’t hear the sound of the trap coming up the gravel drive at the front of the house. It was only when the dog started yapping that she realised she had visitors. Skip, the little spaniel who’d been moping all day, scurried to the door in the hope that his master had at last returned. When he saw that it was not the colonel after all, he retreated to his basket and began to whine piteously.

Mrs Withers descended the stairs in time to see Lottie Pearl conducting two men into the drawing room. Going in after them, she dismissed the servant with a flick of her hand.

‘Thank you, Lottie,’ she said. ‘That will be all.’ As the girl went out, the housekeeper looked at Tallis. ‘I wasn’t expecting you, Major. I fear that you’ve come at an inopportune time.’

‘We’re well aware of that, Mrs Withers. We’re here in an official capacity. You only know me as Major Tallis but, in point of fact, I’m a superintendent of the Detective Department at Scotland Yard.’

She was astounded. ‘You’re a policeman?’

‘Yes,’ he replied, indicating his companion, ‘and so is Inspector Colbeck.’

‘I’m pleased to meet you,’ said Colbeck, ‘and I’m sorry that it has to be in such unfortunate circumstances. You must feel beleaguered.’

‘It’s been an ordeal, Inspector,’ she said, ‘and there’s no mistake about that. However, I must continue to do my duty. The colonel would have expected that of me.’ She waved an arm. ‘Please sit down. Can I get you refreshment of any kind?’

‘No, thank you, Mrs Withers,’ answered Tallis, lowering himself onto the sofa. ‘What we’d really like you to do is to explain to us exactly what’s been going on.’ She hovered uncertainly. ‘This is no time for ceremony. You’re a key witness not simply a housekeeper. Take a seat.’

Mrs Withers chose an upright chair and Colbeck opted for one of the armchairs. The housekeeper was much as she’d been described to him by Tallis. She looked smart, alert and efficient. He sensed that she had a fierce loyalty to her employers.

‘In your own words,’ coaxed Tallis, ‘tell us what you know.’

‘It’s the things I don’t know that worry me, Major – oh, I’m sorry. You’re Superintendent Tallis now.’

‘Start with Mrs Tarleton’s disappearance,’ said Colbeck, gently. ‘We understand that it was a fortnight ago.’

‘That’s right, Inspector. The colonel and his wife went for a walk with Skip – that’s the dog. I think he knows, by the way. Animals always do. He’s been whining like that all day long. Anyway,’ she continued, ‘Colonel and Mrs Tarleton soon split up. She was going off to see a friend in Northallerton. It would have been quicker to go by train or to take the trap but she loved walking.’

She paused. ‘Go on,’ urged Colbeck.

‘There’s not much more to say. She was never seen again and I haven’t the slightest idea what happened to her. Some people claim to have heard shots that afternoon but that’s not unusual around here.’

‘I’m sure it isn’t, Mrs Withers. Farmers will always want to protect their crops and I daresay there are those who go out after rabbits for the pot.’ He noticed the hesitant look in her eyes. ‘Is there something you haven’t told us?’

‘Yes,’ she replied, blurting out her answer, ‘and it’s best that it comes from me because others will make it sound far worse than it is. They have such suspicious minds. On the day that his wife vanished, the colonel was carrying a shotgun. He very often did.’

‘I can vouch for that,’ said Tallis. ‘On the occasions when I’ve been here, we went out shooting together. I can’t believe that anyone would think him capable of committing murder.’

‘Oh, they do. Once a rumour starts, it spreads. And it wasn’t only the nasty gossip in the village,’ she said, ruefully. ‘There were the letters as well.’

‘What letters?’

‘They accused him of killing his wife, Superintendent.’

‘Who sent them?’

She shrugged. ‘I’ve no idea. They were unsigned.’

‘Poison pen letters,’ observed Colbeck. ‘What did the colonel do with them, Mrs Withers?’

‘He told me to burn them but I couldn’t resist reading them before I did so. They were foul.’

‘Were they all written by the same hand?’

‘Oh, no, I’d say that three or four people sent them, though one of them wrote a number of times. His comments were the worst.’

‘How do you know he was a man?’

‘No woman would use such filthy language.’

‘It’s a pity you didn’t keep any of them,’ grumbled Tallis. ‘If anyone is trying to blacken the name of Colonel Tarleton, I want to know who they are.’

‘Well, there was the one that came yesterday,’ she remembered. ‘When I pointed it out to the colonel, he said he didn’t have time for the mail. I think he couldn’t bear to read any more of those vile accusations. In my opinion, they drove him to do what he did.’

‘Could you fetch the letter, please?’

‘I’ll get it at once, Superintendent.’

As soon as her back was turned, Tallis glanced meaningfully at Colbeck and the latter nodded his assent. The superintendent felt that Mrs Withers might be more forthcoming in the presence of someone she already knew rather than when she was being cross-examined by the two of them. Getting to his feet, Colbeck went into the hall and asked where he could find the servant who’d opened the door to them. Mrs Withers told him, then she went back into the drawing room with the letter, her black taffeta rustling as she did so.

‘Here it is, sir,’ she said, handing it over.

‘How can you be sure that it’s a poison pen letter?’

‘I recognise the handwriting. It’s from the man who’s already sent more than one letter. The postmark shows it was posted in Northallerton.’

Tallis scowled. ‘That means it came from a local man.’ He opened the envelope and read the letter with mounting horror. ‘Dear God!’ he exclaimed. ‘Is this the sort of thing people are saying about the colonel? It’s utterly shameful.’

Lottie Pearl was in the larger of the guest bedrooms, fitting one of the pillowcases she’d just ironed. Even though it was too big for her, she was wearing the black dress that she’d borrowed earlier from her mother. There was a tap on the door and it opened to reveal Colbeck. When she saw his tall, lean frame filling the doorway, she moved back defensively as if fearing for her virtue.

‘I’m sorry to startle you,’ he said. ‘Lottie, isn’t it?’

‘That’s right, sir.’

‘I’m Inspector Colbeck and I’m a detective from London.’

‘I haven’t done anything wrong,’ she cried in alarm.

He smiled reassuringly. ‘I know that you haven’t, Lottie. Look, why don’t we go downstairs? I think you might find it easier if we had this conversation in the kitchen.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

Glad to escape from the bedroom, she trotted down the steps and went into the kitchen. Sitting opposite her, Colbeck first explained what he and Tallis were doing there but he failed to remove the chevron of anxiety from her brow.

‘Do you like working here?’ he asked.

‘Yes, I do, sir. There’s a lot to do, of course, but I don’t mind that. My mother always wanted me to end up here in the big house.’

‘It is a big house, isn’t it?’ said Colbeck. ‘I would have thought it needed more than two of you on the domestic staff.’

‘There used to be a cook and a maidservant, sir.’

‘Do you know why they left?’

‘No, that was before my time. Mrs Withers took over the cooking and I was expected to do just about everything else. The girl who had my job was dismissed for being lazy.’

‘How did you get on with your employers?’

‘I didn’t see much of them, sir, but they never complained about my work, I made sure of that. Mrs Tarleton was a nice woman with a kind face. The colonel was a bit strict but Mrs Withers told me that that was just his way. She spoke very highly of both of them.’

‘How long has she been here?’

‘Donkey’s years,’ said Lottie. ‘She came as housekeeper and her husband was head gardener. He died when he was still young and Mrs Withers stayed on. And that’s another thing,’ she added. ‘There used to be three gardeners but there’s only one now.’

‘I see.’

She drew back. ‘Have you come to arrest someone, sir?’

‘Only if it proves necessary,’ he said. ‘Neither you nor Mrs Withers have anything to fear. All we’re after is guidance.’

‘I can’t give you much of that.’

‘You may be surprised. Tell me what happened on the day that Mrs Tarleton went missing.’

Pursing her lips, she gathered her thoughts. ‘It was a day like any other day,’ she said. ‘The colonel went for his usual walk before breakfast with Skip, then his wife joined him for the meal. Later on, he took her part of the way along the road to Northallerton then he went off shooting. He brought back some pigeons for Mrs Withers to put in a pie. I had to take the feathers off.’

‘When did it become clear that Mrs Tarleton was missing?’

‘It was when she didn’t turn up at the railway station. She walked to Northallerton but was going to come back by train. The colonel was very worried. He drove over there in the trap and called on the friend his wife went to see. Mrs Tarleton had never been there. The friend had been wondering where she was.’

Lottie rambled on and Colbeck encouraged her to do so. Much of what she told him was irrelevant but her comments on the village and its inhabitants were all interesting. It was clear from the way that the words tumbled out that the girl had very little chance to express herself at the house. Colbeck had unblocked a dam and created a minor waterfall.

‘And that’s all I can tell you, sir,’ she concluded, breathlessly. ‘Except that I feel as if it’s something to do with me. I mean, none of this happened until I came to work here. It’s almost as if it’s my fault. Deep down, that’s what Mrs Withers thinks. I can see it in her eyes. Mind you,’ she went on, philosophically, ‘there’s some as are worse off than me.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The engine driver is the one I feel sorry for, Inspector. He killed Colonel Tarleton. That’ll be on his conscience for the rest of his life. Poor man!’ she sighed. ‘I’d hate to be in his shoes.’

‘How fast was the train travelling?’ asked Victor Leeming.

‘Fast enough – almost forty miles an hour.’

‘And where exactly on the line did you hit him?’

‘The spot will be easy to find, Sergeant,’ said Hal Woodman. ‘I’m told that some people have put flowers there.’

‘It must have been a shock to you and the fireman.’

‘It were. We sometimes have children playing on the line – daring each other to stand in front of a train – but they always jump out of the way in plenty of time. The colonel just marched on.’

‘Didn’t he just stop and wait?’

‘No, he seemed to be in a hurry to get it over with. It were weird. When we hit him, like, Seth – he’s my fireman – spewed all over the footplate. But we left an even worse mess on the line.’

Leeming had been in luck. Expecting a long search in the town, he was relieved to discover that Woodman lived within easy walking distance of the railway station. It took the sergeant only five minutes to find him and to acquaint him with the reason they’d come to the area. Woodman was a thickset man in his thirties, with a weather-beaten face and missing teeth. He was still patently upset by the incident on the previous day and went over it time and again.

‘Did you know Colonel Tarleton beforehand? said Leeming.

‘Everyone knows the colonel. The old bastard sits on the bench in this town. They reckon he’s a tartar. I’m glad that I never came up before him.’

‘Did you recognise him at the time?’

‘Of course not,’ said Woodman. ‘When you’re on the footplate, you’re staring through clouds of smoke and steam. All we could make out was that it was a man with a cane.’ He pulled a face. ‘It fair turned my stomach, I can tell you. There was simply nothing we could do.’ He rallied slightly. ‘In a sense, I suppose, I shouldn’t feel so bad about it, should I?’

‘Why not?’ asked Leeming.

‘Well, I was doing everyone a favour, really. We all know that he shot his wife. He got himself killed on purpose before the law caught up with him. Yes,’ Woodman continued as if a load had suddenly been lifted from his shoulders, ‘you could say we were heroes of a kind, me and Seth Roseby. We gave that bugger what he deserved and did the hangman’s job for him.’