Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

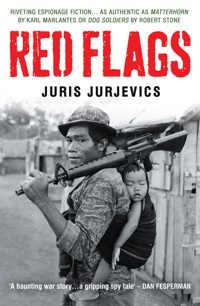

A novel of soldiers and spies in the Highlands of Vietnam Army cop Erik Rider is enjoying his war until he's sent to disrupt Vietcong opium fields in a remote Highland province. Rider lands in Cheo Reo, home to hard-pressed soldiers, intelligence operatives, and profiteers of all stripes. The tiny U.S. contingent and their unenthusiastic Vietnamese allies are hopelessly outnumbered by infiltrating enemy infantry. And they're all surrounded by sixty thousand Montagnard tribespeople who want their mountain homeland back. The Vietcong are onto Rider's game and have placed a bounty on his head. As he hunts the opium fields, skirmishes with enemy patrols, and defends the undermanned US base, Rider makes a disturbing discovery: someone close to home has a stake in the opium smuggling ring-and will kill to protect it. Written by a master, and as authentic as Matterhorn or Dog Soldiers, Red Flags is a riveting new addition to espionage fiction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RED FLAGS

Juris Jurjevics

NO EXIT PRESS

For Jeanne,

BELOVED CIVILIAN

Neil Olson,

AGENT PROVOCATEUR

And for the guys …

JAMES 51609945 PEARSON • HARRY PEWTERBAUGH

JERRY ROWLAND • ELLSWORTH C. SMITH

GEORGE RUCKMAN • RICHARD STOLZ • FRANK DEVIVO

JEFF BARBER • BERNIE GELLMAN • JERRY GOLD

MO MOSER • LOU NAPOLITANO • MICHAEL SEFTAS • RALPH MUIR

DAVE CADWELL • GLEN CASPERSON • ROGER BENNETT

BOYD RILEY • VIRGIL PROBASCO • RALPH GOLD • SGT. HAYDEN

STEVE “PTERODACTYL-27” HARRISON • LARRY “DOC” WHITE

MAJOR FRANK • THE LATE ED SPRAGUE • STEVE LARGE

MELTZER … AMESWORTH … MILLER … WEST … SHAEFFER …

LEWIS … MARSHALAK … SHEA … SEAN …

GILLESPIE … MOORE … SGT. ROBBIE • SGT. HUFNAGEL

KEN FORRESTER • MAX LUND • JIM O’MALLEY • JIM ELLIS

EDMON TAUSCH • JOE PICKEREL • KSOR KUL • THE LATE SIU BROAI

REVEREND BOB REED • JĀNIS ROZENS • JURIS MEIMIS

ALEKS EINSELN • IGORS MOCALKIN • BILL COMREY

CARL HOPP • BOB SHOOKNER • THE LATE WILLIAM LANDECK

JOHN SCHEURLEIN • JOSEPH TROXELL • JOHN RUSSELL

DOUG BULEN • JOHN PETERSON • ED GREGORY • GARY BARTRAM

TIM MCGUIRE • RICHARD ADAMONIS • GERRY FLAVIN

FRANK VERTUCA • JOHN SPINA • JIM MORRIS • DOUGLAS BEY

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER • NELSON DEMILLE • GEORGE E. DOOLEY

JOSEPH FERRANDINO • MIKE LITTLE • JIM HARRIS • JAMES DINGMAN

WILLIAM PELFREY • THE LATE GUSTAV HASFORD

But most especially this is dedicated to those — friends and foe — we light the joss sticks for who didn’t make it home.

The only tribute you could really pay, and I can still pay, is to remember. What else is there?

— Clark Dougan in Christian G. Appy, Patriots

Mike, you’re talking well, but where are your facts? You state things so glibly. What percent of territory has the government lost in the last month? What percent does it have and what percent does it not have? Where are your statistics? Don’t give me poetry.

— U.S. secretary of defense Robert S. McNamara

in A. J. Langguth, Our Vietnam

“This is the place where everybody finds out who they are.” Hicks shook his head. “What a bummer for the gooks.”

— Robert Stone, Dog Soldiers

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PROLOGUE

SOMEDAY WAS STANDING on the gravel in front of Bert’s store, collar turned up against the cold.

I knew right off. It wasn’t like I hadn’t been expecting her. Once, when she was an infant, I had imagined her. The grown version demanded a quick revision. She was a stalk. Maybe a twenty-four-inch waist, a bust not much bigger.

“I’m Erik Rider,” I said. “How can I help you, Miss …?”

The lips were her father’s, the hazel eyes soft, like her touch as we shook hands. The bones felt hollow — a bird’s, they were so light. Like his when we recovered the body.

“Celeste Bennett,” she said. “Sorry to just barge in on you.” She withdrew her hand.

“Pleased to meet you,” I said, although pleased was the last thing I was.

“You knew my father. I was hoping I could talk to you about him.”

“Colonel Bennett …? Dennis Bennett?” I weighed my words, pretending it was taking time for me to recall the man, as though I hadn’t thought of him pretty much steadily for nearly forty years. I launched into my fine-man, exceptional-officer patter. An honor to serve under him. From her impatient expression, I could tell she’d heard all the customary guff before and wasn’t buying.

“Mr. Rider, I’d really like to —”

“How on earth did you find me?” I said, feigning the most genuine curiosity, anything my face might conjure by way of camouflage.

“Your ex-wife.” She brushed the hair off her forehead.

“Which one?”

“Hillary?”

“Wife number three.”

She looked away, nervous. She had the colonel’s angular nose too. His kid all right. Her eyes caught me again.

“She said you were in northern California, around Redding, but she wasn’t sure where. You weren’t listed … or even unlisted. I did a title search online and saw you had property near Creek. I took a chance.”

She pulled her gloves on and hunched against the cold.

“Title search, huh? What is it you do in the world?”

“Lawyer. I’m a lawyer.”

Shit, I thought. “How old are you?”

“Thirty-eight.” She shifted her feet, uncertain. “I was conceived the last time they were together, in Hawaii,” she said, by way of corroborating herself, as if that were at issue. “And you?”

“I don’t know where I was conceived. Probably the back seat of a Nash Ambassador in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin.” She didn’t blush and she wasn’t laughing. “Sixty-three this year. I’ll be sixty-three.” I indicated the macadam behind me. “You drive in from Red Bluff?”

“Yes. I’m still swaying. That’s some twisty road.”

I looked west, toward the higher turns through the pass. Some of it I’d driven yesterday, the S-curves dusted with snow.

“Yeah. There’s two more hours of mountain road before you hit the Pacific Coast Highway.”

I waved to Bert, visible just behind her in the big window of his grocery store. He had called to summon me down — “There’s a gal here looking for you.”

She glanced back at him. “Your friend volunteered that he had a weapons permit. His wife also.”

I nodded. “Yep. Most everyone here carries. Not many citizens bother with permits.”

She squinted against the winter sun. “Why all the weaponry?”

“The nearest law is in Weaver, two hours away. Takes them a day to get here, when they come. Which is why Bert’s wife has her pistol out when she takes the night receipts to her car. They make their permits and weapons known to everyone, especially strangers.”

“The neighborhood’s that dicey?” she said.

“It’s isolated.”

“Looks so idyllic.”

“There are temptations.”

She took in the tiny post office and Bert’s grocery store and bar, the two connected through a common wall. “I hadn’t noticed,” she said. “The sign coming into town put the population at twenty-five.”

“Sounds about right.”

“Not a lot of nightlife in Creek, I take it.”

“Bert’s bar is it. The temptation’s up on the ridges. The hills are full of marijuana farmers, if they’re not cooking meth.”

She scanned the voluptuous green slopes and pine groves all around us.

“They grow the dope in small patches,” I said. “Can’t be spotted so easily from the air. Reduces losses if a field gets busted. They’ve got armed illegals guarding them.”

“Should I worry?”

“It gets a little rowdy some nights at Bert’s.” I pointed to the unlit neon sign in the saloon window behind her. “Otherwise they’re respectful neighbors.”

“Your wagon full of firearms too?” She looked over at my Bronco, probably scanning for a gun rack.

“No. I haven’t kept company with a weapon in a long while. So I have to be especially polite.”

A momentary silence fell between us. I was forgetting how to have a conversation.

“How did you come to settle here, Mr. Rider?” she said, her tone light, like we had just met at a cocktail party. She was pretending interest in my life to keep me talking, coaxing the reluctant witness.

“Came for a month years ago,” I said. “Never left. A pal from the service asked for help building his house, a few towns over. He had a crop-dusting business, spraying walnut and almond trees from a helicopter.”

“The signature sound of your generation,” she said.

“What?”

“Those blades beating the air.”

“Oh … yeah. I suppose.”

The day was bright and crisp. A cloud and its shadow passed, and the air turned colder beneath it.

“About my father.” She put a gloved hand on her rented car and leaned a hip against the rocker panel. “You’re the thirteenth member of the advisory team I’ve found.”

If she was just running through the roster, I could pass her along — fast. “Guess I was next on the list.”

“Not exactly. The last couple of men I spoke to wanted to know if I’d seen you yet. So I moved you up.”

I was tempted to ask who but suppressed the urge. Instead, I lifted my tattered Dodgers cap, scratched my head, and made homely noises, stalling with hick gestures.

“I didn’t know the colonel well. I was just a captain. He was fifteen years my senior, my superior officer. We didn’t exactly socialize. You know, you might try his executive officer, Major Gidding.”

“General Gidding passed away three years ago. He was the first one I found.” She held back wisps of hair fluttering around her face. “Two others are deceased as well. Two begged off. The seven who agreed to meet weren’t very forthcoming. Mostly I get lofty sentiments about valor and honor.”

“Your mother wasn’t …?”

“Told anything? Other than being instructed not to open the coffin, no. Not really. She was so shattered — widowed, pregnant. She just let the protocols and ceremonies carry her along. He was buried at West Point. Afterward it got even tougher for her. A while later I arrived.”

“You weren’t enough to keep her occupied?”

“Yes. Yes, I fit the bill,” she said, sounding impatient, as if being her mother’s diversion had been a challenge.

“What did your mom tell you about your father?”

“That he wouldn’t have died if he had cared more about us and less about his career.”

“Really?” I said, taken aback.

“Mom wanted him to stay an instructor at West Point. She said he had real gifts as a teacher and she didn’t see why he felt he had to be an infantry officer. At times I wondered why they had ever been together. He was from a military family. She hated the military, hated all the deference expected of an officer’s wife.”

“Being an Army widow’s no picnic either.”

“My whole childhood she was furious with him for going back to Viet Nam when he didn’t have to. She couldn’t forgive him. I couldn’t bear to listen to it. I’d wind up defending him.”

“A lot of us volunteered for more tours or extended them. Didn’t his awards —”

“‘For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action while serving as commanding officer …’ blah-blah-blah. I could recite the medal citations when I was in grade school, before I even knew what all the words meant. Not much of a substitute for an actual dad.”

She was his daughter. Tall, thin as a rail, with that same anxious concentration. The wind rushed through the treetops, swaying the branches.

“Except for those damn citations, I have only my mother’s version of who my father was.”

“I can see that.”

“I wanted to hear about him from people who knew him as a soldier — knew him at the end.” She wrapped her arms around her middle, fighting the chill. “A lot of people go to where their loved ones perished to commune with those they’ve lost: to the site of a plane crash, the spot on the highway where someone they loved was killed. For a long time I thought I’d sense something if I did that — found the place where he died.”

I winced. “You’re actually thinking about going back there?”

She blinked rapidly. “I did, last year.”

Why was I surprised? Young Americans were honeymooning in Ho Chi Minh City these days, frolicking on the beaches at Nha Trang.

“I take it you didn’t find what you were after.”

She shook her head. “Never got further than Saigon. The aborigines in the mountains were demonstrating against the government. The authorities wouldn’t let me into the Highlands.”

“Yeah, they’re crushing the Montagnards again, poor bastards. So you’ve come here looking for what you couldn’t find there?”

“I’m hoping.” She shielded her eyes against the cold sunlight. “I want to know what he was doing when he died … if it was true he stupidly put himself in harm’s way. I want the facts — unvarnished.”

I knew a bit about piggybacking ghosts around and I hesitated, reluctant to disturb hers. She slapped the car, exasperated.

“I’ve gotten the platitudes and pats on the head. Honestly, I don’t want to be spared. It’s just impossible when you don’t know. It never leaves you.” Her eyes cut me. “No matter what the truth is, I need to hear it.”

And her gut told her she hadn’t yet. I knew the war had burrowed into those of us who had been there, but it was disturbing to see it haunting someone her age. She was stuck with her grief, mourning the father she had never known.

The wind plastered our jackets against our arms and torsos. She trembled, ears crimson. Bert’s neon saloon sign went on in the window. The regulars quickly appeared, crunching across the gravel.

“Mr. Rider, I can’t keep standing here in the cold. Let me at least buy you a drink.”

“Erik. Please call me Erik.”

We went in. Bert’s wife was filling glasses. The TV played, barely audible, stock quotes and news streaming above and below a talking head. I ushered Celeste to a booth, found out what she drank, and fetched it. She sipped her bourbon. I downed my shot and tipped back a Kirin.

“Haven’t much time,” I said, checking my wristwatch and feeling the fool for using the transparent dodge of pressing business. She looked exhausted, finding it difficult to keep pleading her case. I needed to do the smart thing and brush her off.

“Whatever you can spare,” she said, her voice calming. She took slow, deep breaths, keeping herself contained — patient — even as her heart raced. I could see the pulse in her throat. She was revving for something.

“You look a little peaked,” I said.

“Haven’t eaten since morning,” she admitted, sipping again. “Didn’t want to stop.”

I signaled Bert’s wife and she threw on two bison burgers.

Celeste. Young, alive, and tortured. It was palpable. Even sitting, she moved constantly, darting from side to side just a fraction, as if boxing against somebody in there with her.

“Did you know my dad in Saigon in sixty-four, before Cheo Reo?”

Smart. She was easing me into it. Okay, Saigon was the easy part. I fussed with the chipped Formica and nodded. “I knew who he was.”

“How bad was it?”

“There were street demonstrations. Occasional bombs. Otherwise Saigon was pretty much a great duty station early on.”

“Oh,” she said, surprised.

“Minimal bullshit, quick advancement. Sleepy, tropical. Palms, tamarind trees — like that. Exotic food, exotic women. New Orleans, with bigger and better guns. Perfumed with flowering trees and marsh water and every kind of shit, human and otherwise. I actually miss it. There were only sixteen thousand of us in country then. Most commuted to the war, did their work, and hustled back to town before sundown. We slept in real beds in real linen.”

“There was fighting though, right?”

I shrugged. “The guerrilla war wasn’t much, just hot enough to qualify us for hazardous-duty pay and put a little zing in life. Shootouts stayed in the hinterlands, but most of the fighting was small time — dinky and dien cai dau: crazy. The Viet Cong just kept sawing away at the Vietnamese military, a piece at a time. They’d take potshots, block roads, hit and run. Drop three mortar rounds on us and be gone before the last one landed.”

“But the Viet Cong had such a fierce reputation.”

“Yeah, well, in those days the VC didn’t even have enough weapons to arm all their fighters. They had to take turns with them — a sad hodgepodge of copies and discards, all different calibers. When they attempted larger attacks, they’d herd villagers into nearby fields to yell and set off firecrackers … to sound like there were lots of them.”

“Doesn’t seem like much of a war,” she said.

“It wasn’t. More like a bad neighborhood you policed during the day and stayed out of after dark.”

Mrs. Bert delivered our bison burgers and the condiment tray. I removed the cap from the mustard. Celeste worked on her burger and waited for me to resume.

“The VC owned the night, we owned the nightlife. The young sergeants partied, the middle-aged noncoms invested in real estate and bars and lived with Asian mistresses they married in Buddhist ceremonies — or not. A lot of servicemen and embassy staff had their dependents with them.”

“Wives?”

“Yeah, kids too. Families leased villas in good districts, with pools and tennis courts. Had peacocks wandering the lawns. Cooks, amahs, gardeners … a swim before lunch, a round of golf at the Saigon Golf Club in the afternoon.”

“Sounds like an American raj,” Celeste said. “My mom never mentioned that she could have gone with him. I could have been born there.” She sat quietly for a minute, absorbing this possibility.

“Was it exciting?” she said. “Exciting enough to make someone want to go back?”

“Sure. Boring too. Funny every once in a while.” I slathered some ketchup on my burger. “Listen, it was never neat or simple. There wasn’t just one war, us against them. There were a bunch of wars all going on at once. You had to sort through them. You weren’t always sure which side you were on.”

I took a pull of beer.

“By the time I served under your dad, two years later, Viet Nam was going through its top bananas like a fruit bat. They were on coup number eight. President Diem ruled for nine years. His successors were lucky to last nine weeks. Every time a regime was taken down, counterinsurgency stopped, the government and army derailed. Then the latest junta generals would replace all the civil and military leaders with their guys and it all started up again.”

Action on the tube elicited a small outburst from the sportsmen gathered at the bar. They high-fived and locked on the screen. I took a healthy swig and felt the alcohol bathe my tensed brain. I had to watch it. She was good at getting people to talk. I needed to back away. I waved to Mrs. Bert for the tally.

“Where are you heading from here? Who’s next on your list?”

She peered out the window. It was getting late. White flakes threaded the air.

“I’m not sure I should try that road in the dark and the snow.” She looked toward the bar. “Mrs. Bert rents rooms, I hope.”

I shook my head. “It’s not a bed-and-breakfast sort of town.”

“Damn.” Concern swept over her face. “Might I impose on you, Erik?”

What was there to say? Outflanked. “Where’s your stuff?”

“Front seat of the rental.”

Mrs. Bert eyed us as we left the bar; the regulars paid no attention. Not minding other people’s business was the only town tradition I knew of, other than shooting up Bert’s parking lot on New Year’s Eve.

“Your place is beautiful.” She sounded surprised. And relieved.

I’d driven her up in the Bronco. Her rental never would have made the steep grade.

“Yeah,” I agreed. “Hard not to be, with that vista.”

The sun set like a boiling rock, turning the Trinity Alps dark green. Faint remnants of gold from below the horizon rounded the rolling hills.

The cabin sat on the edge of a steep drop, giving the back porch an enormous view of our valley, nestled in green twists and slopes. There wasn’t another house in sight. The faint whiff of wood smoke was the only sign of other human habitation.

“Do you mind the isolation?”

“I’ve come to like it.”

She put her things in the room next to mine and returned to claim the armchair in front of the hearth. It was growing colder as the light outside died.

I said, “Would you fire up the kindling in the fireplace? It’s all set to go. The matches are by the hearth, on the log pile.”

She knelt to ignite the wood shavings and splints, baring a band of skin at the small of her back. The room filled with the aroma of apple wood and sage as the scrap caught. Celeste stood up and paused at the framed photos on the mantelpiece. She spotted her father in a group shot.

“I don’t have this one. Is this Team Thirty-one? I recognize a couple of faces.”

“Yes, some of it.”

“You guys ever get together?” I shook my head but she didn’t see; she was still examining the photograph. “No,” I said. “We don’t.”

She looked back, holding my gaze for a moment, weighing something about me. I held up a bottle of fifteen-year-old whiskey. She nodded yes and I got down the cut-crystal glasses, bringing everything over to her. Nothing like kick-ass whiskey in a heavy tumbler. The fragrance alone revived me some. Celeste resettled in the armchair, covering up in a quilt.

“Why do you think he volunteered to go back?” she said.

“To get another crack at a field command, maybe. Career officers needed that on their resumés to advance. That and gongs.”

“Gongs?”

“That’s what GIs called medals. You needed gongs and a field command or you’d be out of the running for promotion and eventually out of the Army. The higher you went, the harder it got. It was like musical chairs.”

“So my mother was right. He was as ambitious as the rest of them.”

“General Westmoreland allotted six-month combat commands to as many officers as possible. He rationed them because the fight was going to be over right quick.”

“Did you think it would be done that fast?”

“No, but they didn’t ask me or other ordinary mortals.”

Her cheeks were rosy from the warmth of the fire. I knocked back my drink.

“Whole regiments of North Vietnamese regulars came streaming across, accompanied by Chinese generals advising them. The local Viet Cong armed up too. No more improvised bombs made out of rice husks and sugar. Forty miles north of Saigon, the South Vietnamese lost three hundred men in one ambush, including four U.S. advisers. Just to make sure they got our attention, the Communists decapitated the Americans.”

“Good God. Why?”

“Beheading was real popular. The VC decapitated local officials all the time and dumped their heads in the toilet. Burying people alive was big too. Four Americans beheaded, though — the message was clear. We weren’t immune. It wasn’t going to be a cakewalk if we were truly getting in the fight. The unwritten rules changed as well.”

“What rules?”

“They’d never gone after American dependents: no attacks on wives or school buses. One afternoon in Saigon, two VC killed the MPs guarding a movie house and then rushed into the theater with a bucket full of arsenic sulfide and potassium chlorate they’d picked up in a pharmacy. The bomb wounded a lot of our civilians, killed an officer.”

I wedged the logs closer together with the poker and stood with my back to the fire. Wrapped in the quilt, she looked tiny.

“They car-bombed our billets, restaurants, the embassy, set off a bomb at a baseball game out at Pershing Field. It was open season on Americans. Dependents were ordered out, the Marines and combat battalions in — two hundred thousand of us. There was no mistaking what was coming. The intelligence on the North Vietnamese elite clinched it.”

“What intelligence?”

“That their local officials, their foreign minister, even the mayor of Hanoi — they were all sending their sons and daughters of military age out of the country.”

I banked the fire and unfolded the metal screen. The aroma of the fireplace mingled with her scent. I was wound up, mulling the lost crusade.

“Well, Communism didn’t win either,” I said, sounding regretful. “The old corruption is eating the new Communist state alive.” I raised my glass in a toast. “To each according to his greed.”

I slumped onto the couch. Even fatigued, she looked pink and delicate, her hazel eyes clear and penetrating, hair luxurious, cheeks perfect. Her teeth were rabbitty though, big, with a gap between the two in front. The imperfection seemed childlike and endearing.

I asked if she wanted coffee; she said she did. I rose to make it, but she waved me back down. “Let me,” she said.

Celeste braided her hair while she waited for the water to boil. Been squatting in the woods too long, I thought. Horny at the proximity of a girl twenty-five years my junior. Or maybe apprehension was revving the hormones. Either way, my vision sparkled.

She was efficient. The café filtre press was soon on the coffee table. She poured out our cups.

“Your tour,” she said, “when you served with my dad.” She handed me a cup. “What happened in Cheo Reo?”

I took a sip and didn’t say anything.

“If you’re worried about sparing my feelings,” she said, “don’t.”

Had the time come for her to hear it?

“I’m aware he was burned. Mom didn’t listen to the warning not to open the coffin. My gran said it was two years before my mother slept through the night. What was the slang for it — crispy critter?”

I stared into my coffee. “I’m sorry. Family shouldn’t have to —”

“Yes, we do. We do have to … even that.” She pushed back her hair. “He was a husband, soon to be a father. How could he have been so cavalier?”

“He wasn’t,” I said. “Your mother married a professional soldier. Your dad went back because that’s where the war was. If she couldn’t live with that …” I took a slug of java. “But honestly, I don’t think I’m up to talking about —”

She cut me off. “Out of fifty-eight thousand, two hundred and sixty-three casualties, do you know how many full colonels, like my father, died in Viet Nam?”

I shook my head.

“Eight. Pretty damn rare, wouldn’t you say?”

“Very.”

“Did you hurt a lot of people in the war, Erik?”

“More than I wanted. Why?”

“Do they haunt?”

Something had shifted in her tone and my comfort level. Suddenly I felt like a hostile witness.

“I’m not sure where you’re going.”

“Some of your former comrades intimated my father didn’t die as officially reported.”

“You mean — not in combat?”

She froze, realizing what I might have let slip. “Are you suggesting he wasn’t killed in action?”

“Who did this intimating?” I said, evading the question.

“It’s not important. What’s germane is they implied you were involved.”

I closed my eyes for a moment, tilting my head back.

“Were you?” she said.

“Was I what?”

“Did you have any part in it?”

“Not the way you seem to be thinking.” I opened my eyes.

“One person referred to you as Captain Sidney. Said you weren’t who you appeared to be.”

“Maybe because I wasn’t. Listen —” I held up a hand, stopping her as she was about to press me again. “If I tell you … you have to put it away and move on.”

“I’m not sure I can promise that.”

I went to my jacket hanging on the wall rack and slipped my wallet from the inside pocket. I took out the military scrip I’d carried since the sixties and unfolded the mauve and green “funny money” on the coffee table.

“What’s this?” she said, peering at the woman’s profile printed in place of George Washington’s on the military money.

“You’re a lawyer. It’s a retainer.”

She let the peculiar-looking dollar sit on the low table between us.

“You feel you need a lawyer?”

“I need attorney-client privilege.”

“Why?”

“There’s no statute of limitations on what you want to know.”

Her face hardened; she was no longer anyone’s child. Someday reached out and picked up the bill.

1

MISER GOT US rooms at the Five Oceans in Cholon and we went out to get reacquainted with the city. Saigon was still sordid and fabulous. Neither of us had eaten actual food since departing San Francisco so we indulged ourselves, feasting on lobster and salted crab at classy La Miral and then savoring small dishes of unimaginable flavors cooked in modest family restaurants with just a few tables in the yard, sampling morsels of eel grilled on stove carts in the street and unidentifiable meat smoldering on braziers yoked across the cooks’ shoulders on chogie poles and lowered to the curb. We strolled on, flirting with all the other food on offer: shrimp from the Saigon River, sparrows roasted in oil and butter, frogs’ legs, skewered snake, buffalo-penis soup, steamed mudfish, baked butterfish, shark. We finished at the open-air place near the Old Market that had cobra on the menu and bananas flambé for dessert. Both of us settled for espresso.

We walked again under the brilliant crimson blossoms of the flamboyante trees, moved through the flower market and avoided clusters of Vietnamese draft dodgers who idled on shady street corners hustling hot watches. At the PX, GIs and the odd American deserter scored reel-to-reel tape recorders and electric fans for locals to resell at inflated prices. Chinese drug dealers scooped coke off sidewalk tables with elongated pinkie nails, and Macanese hoodlums carted bricks of cash to their moneychangers. Outside the British embassy, turbaned Gurkhas guarded the gates while, close by, street urchins hawked oneliter bottles of gasoline. Whatever lit your fire, Saigon had it all.

Astrologers trading in futures, mama-sans extolling taxidermied civet cats and live bear cubs. Stick-thin men selling U.S. Army-issue rations and assault rifles, flak vests, toilet paper, jackets made from GI ponchos lined with speckled parachute silk. Whether it inflicted pleasure or pain, whatever you desired was yours. Hell, armored personnel carriers and helicopters if you had the cash, a howitzer for four hundred bucks, an M-16 rifle for forty, a woman for ten. Or a tooth yanked out curbside for a dime.

We ambled past clubs with live bands imitating famous rock groups, and Cholon gangsters taking their leisure in open-sided billiard halls. Near the Central Market, refugees squatted in giant sections of stockpiled sewer pipe. We stepped around night soil and lean-tos on the pavement. Lights burned in MACV SOG and in General Westmoreland’s old office on 137, rue Pasteur. The brass was working overtime.

In the morning we put on our work clothes — civvies — and reported to the Headquarters Support Activity, Saigon (HSAS), office. A dozen of us worked out of the rickety place, not much more than a bunch of desks. We were special agents loaned out to HSAS by our various investigative and counterintelligence agencies — ONI, OSI, CIC, CID. U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, and us — U.S. Army, “El Cid.” GI slang for Criminal Investigation Division; “Sidney” behind our backs. The work didn’t make us popular with our fellows, who considered us barely better than snitches.

No investigators were commissioned officers, although we frequently went undercover with officers’ ranks. Our mandate was mainly to investigate crimes against U.S. personnel and property. Miser and I had been teamed up for a couple of tours, him an E-7 noncom, me a warrant officer, a rank halfway between the lowliest lieutenant and the highest-ranking sergeant. Early on we investigated the occasional homicide, but mostly we looked into the pilfering of supplies, scams like selling the U.S. military thousands of inedible eggs for thousands of American breakfasts, and the unexplained deaths of dozens of sentry dogs. As terrorist acts began to target U.S. personnel and dependents, the American head count rose steadily, along with our caseloads. We didn’t get much support. Our little outfit had to improvise even as we found ourselves investigating suicides, rapes, security violations, even espionage and treason.

Our boss, Major Jessup, gave us a perfunctory welcome-back and instructed us to trade our civvies for jungle fatigues and fly up to Pleiku to investigate a threat against a company commander who had called in artillery on his own position, earning him a medal for valor and a bounty on his head of eight hundred and seventy dollars. Not from the VC; from his own men, for shelling some of their buddies into hamburger. The brass hats loved their heroic young West Point star. Eighty-seven recent high-school graduates had pledged ten bucks apiece to see him dead.

“Local talent in Saigon would’ve done it for fifty,” Miser growled. “The kids could’ve saved their fucking pennies.”

“Never mind that, Sergeant,” Jessup snapped.

The U.S. Army wasn’t about to charge nineteen-year-old survivors of horrific combat with mutiny and solicitation of murder. The solution was obvious; Major Jessup strongly suggested we put it into effect the moment we got to Pleiku: “Get his ass out of there!”

“Yes, sir,” we answered.

The second case Jessup assigned us was out in the boonies and wasn’t going to be anywhere near as simple or quick.

A chunk of our work involved GIs’ attempts to smuggle dope home: cannabis and heroin, both extremely high grade and insanely cheap. The purest scag went for a dollar or two a dose, commonly sold roadside by kids. A buck would buy you the quintessential experience of the exotic East: a dozen pipes in an opium den. Fifty dollars got you six pounds of marijuana, though most everyone bought rolled joints, ten for fifty cents, or special cartons of Salems — ten bucks instead of the two you’d pay at the PX. The Salems were perfectly repacked by hand with opiated grass, and the carton artfully resealed so you couldn’t tell it had ever been opened.

All you had to do was step up to the perimeter wire anywhere holding a sprig of anything, and you’d be set upon by vendors of marijuana and heroin. Business indicators were all good. Mainlining GIs were on track to outnumber stateside addicts. Normally the South Vietnamese drug trade was off-limits, untouchable, none of our concern. Saigon was a smuggler’s wet dream, as Miser often pointed out. We couldn’t even arrest Vietnamese nationals who were stealing from American supply ships and American supply depots, much less the ones smuggling narcotics in and out of their own country. Besides, transporting and refining them was practically a South Vietnamese government enterprise. Which is why the second assignment came as a surprise.

The major said, “We need you to bust up a drug operation in one of the Highland provinces.” Miser and I exchanged glances, wondering if the major was serious. “Half the proceeds turn up like clockwork in the Hong Kong bank account of a Viet Cong front organization. Their cut’s way too big to be just a tax or a toll. Which means the VC are in partnership up there — in business with somebody.”

He paused to see if he’d gotten our attention. He had.

“Since the forties, the Communists have sold captured Lao opium to traffickers in Hanoi to help finance their arms purchases, and even bought quantities to sell. But actually growing dope … that’s new. They denounce the imperialist French for their government-sponsored drug dealing, but evidently the North Vietnamese need an infusion of U.S. dollars to buy supplies, so they’ve parked their ideology while they stock up on arms and ammo. You with me so far?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. The money the VC are banking is major. Ten times their usual five- or ten-grand rake-off. An informant puts this cash crop of theirs somewhere in Phu Bon Province.”

“Sir, do we know what kind of dope they’re growing?” I said.

“No, and I don’t particularly care.” Jessup assumed his best handson- hips command posture and looked us each in the eye. “No way we’re going to wipe out their drug trade, that’s for sure. The Vietnamese and their neighbors have been at it for five hundred years. Screw the dope. I don’t care if they’re growing pistachios. The higher highers don’t want our guys getting the bang from those bucks. Slow the cash. They don’t like their having so much capital. The buying power needs to be contained — at least for a while. Sabotage as much of the money as you can for as long as you can. And then bail.”

“What are our specific orders, Major?” I said.

“You heard ’em: fuck up their revenue stream.”

“But how, sir? I doubt the money ever touches down in that province, just shifts from one Hong Kong account to another. So what do we do? Kill their pack mules? Kidnap their women?”

“Do it any way you can. Just don’t tell me about it. Especially if it’s hinky.” He tapped the unit shield hand-painted on the piece of plywood mounted on the wall behind him bearing the CID motto: DO WHAT HAS TO BE DONE.

What he meant was, since we didn’t have any jurisdiction over Vietnamese nationals — couldn’t arrest them, couldn’t so much as detain them — he didn’t want to know about us getting over on any South Vietnamese who might be involved. No such strictures applied to Communists who got in the way. Their only right was to sacrifice themselves for their cause. So we had to make a case for any casualties being VC if it came to that, and stick to our story.

Miser assumed his Oh, great look as we stood at ease in front of Jessup’s desk while the major finished speechifying. He gave us nothing to go on — neither where to start looking for the operation nor what to do once we found it. Zilch. The absence of direct instructions kept him conveniently free of blame for whatever we wound up doing. Never mind that it left us in the dark about how to carry out the assignment. That was our problem.

As usual, we were to do our work unnoticed: fall back on our early occupational specialties as signalmen, put on field uniforms, and pass as regular soldiers. Or as the major put it, “Do your thing and get out of there as quietly as you came.”

“Will the commanding officer know what we’re about?” Miser asked.

“No. Nobody. And keep it that way.”

A month earlier, an American general had been court-martialed for dealing American arms to God knows who. The shock was still reverberating around Saigon and the Pentagon. If Major Jessup had hung his personal motto on the wall, it would have read TRUST NO ONE. Beginning with him.

“The less they know, the better,” Jessup said.

Which was perfectly okay with Miser and me. The rank and file didn’t exactly love us, and this little chore wasn’t going to be quick or easy. Still, law-and-order work for the Army was way more interesting than coaching the South Vietnamese on how to wage war. Miser and I had both done our time as advisers before signing up for the Army’s agent training course; he a former Pittsburgh cop, me the brat of a widowed Wisconsin county sheriff with my own cell to sleep in on the nights he pulled the graveyard shift.

Jessup tossed me some captain’s bars. “Congratulations. You’re a captain — for the duration.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“I want ’em back when you’re done.”

“What about me, sir?” Miser said.

“You’re perfect the way you are, Sergeant.”

I said, “Can we talk to the informant who linked the Hong Kong account to this Phu Bon Province?”

“Try holding a séance.”

We left. Outside, I said to Miser, “Have you ever heard of the Communists growing dope?”

“Fucking never. The Viet Cong tax the smuggling and retailing and will traffic the shit to finance their war effort, but they don’t produce it.”

I turned to Miser. “Sending us is odd, don’t you think? Viets with police power and fluency in the language would make more sense. Unless our masters don’t trust the Vietnamese to get to the bottom of it.”

“Now, Mr. Rider, why ever the fuck would you say such a thing?”

2

UP IN PLEIKU, we extricated the company commander with the bull’s-eye on his back and saw him safely off to Nha Trang. After which the two of us rostered to fly out on the only regular flight that made a stop in the province capital of Cheo Reo. The six-seat, single-engine de Havilland Otter was an oversize Canadian bush plane, totally reliable, totally slow. The nose housed its one enormous motor and the shaft on which spun the single propeller in a blur in front of the windshield. The landing gear didn’t even retract. Crossing Pleiku at two thousand feet, we passed over the city’s fifty thousand souls napping through the worst of the midday heat. Below us, across the red laterite prairie, stretched the long runways of the air base, Titty Mountain, the evacuation hospital, Camp Holloway, the MACV compound, and the billboard antennas on Tropo Hill, big as apartment houses.

The plane droned across the cloudless Asian sky on a long circuit of stops, carrying the two of us passengers and a large heap of courier pouches containing classified paper. The one saving grace was the instant relief altitude brought as the air turned dry and cold. It was better than sex.

The pilots, in gray jump suits, lounged at the controls, unfazed. They sported shoulder holsters and yellow-lensed, aviator-style shooting glasses, like they were spoiling for a dogfight over goddamn Darmstadt. This in a courier plane with no armament and one lousy engine. The pair of them sat in the elevated cockpit, with us in the well of the fuselage behind them. It was too dark to read by the light of the dirty porthole window, so I rubbed the pane with my elbow and gazed out at the vast green growth that ran to teal toward the mountains. Behind me, Sergeant Miser snored.

Why had I come back?

On my leave a year before, I’d eloped with the girl I’d loved since high school. Months later, that tour finished, I headed stateside, my Army hitch done. Twelve hours after landing in Tacoma I mustered out, a newlywed, although technically we’d been married half a year. She was in graduate school in New York. I was barely in the door, she said I smelled different and that we were history. I stopped. I was standing on a land mine. She’d withdrawn to a safe distance, entered the future alone. I was still thirteen time zones away, my night her tomorrow.

“How could you do this if you love me?” I said.

She gave me a tender look. “I couldn’t.”

Not sure what to do, I walked along Broadway, diagonally down the island, carrying my life in a valise like a refugee, one foot following the next along miles of insect-free concrete. People stared at my uniform but no one came near me. Increasingly I felt unlike my contemporaries— a stranger in my own life. I had a month-long going-away party by myself in a series of bars and then re-upped. Volunteered for another go-round in Southeast Asia. I went back on the levy and ran into Staff Sergeant Miser at Fort Dix.

As he often did when inebriated, Miser started crooning a pop song in a rich baritone: “ ‘Cross the ocean in a silver plane, see the jungle when it’s wet with rain …’ ” He was coming off leave and nursing a pint. Miser hummed a couple more verses, then abruptly stopped to complain.

“I haven’t a fucking prayer of living on fucking Army pay stateside,” he said. “Every leave, I bunk in cheap-ass bachelors’ quarters on base, shop only at the dippy PX, eat shitty mess-hall grub on the government, drink cheap at the NCO club, even fucking bowl on the freakin’ base, and I still come up short at the end of the motherfucking month.” He shook his head. “Overseas is the only place for assholes like us. No taxes. Extra pay for hazardous duty. Food allotments …”

Miser liked intimidating officers with his foul mouth and swagger. The only thing he liked better was boasting about his contacts and overseas investments. He owned shares of massage parlors in Qui Nhon, a truck wash in Long Binh, two laundries in Saigon, a bar in Kontum, and a piece of a saloon and a film-production shop in Bangkok. I didn’t want to know what kind of films.

Nam, he argued boozily, was wide open and free in ways only a besieged society could be. Regulations were lax. Hell, everything was available, removable, salable. Nobody sweated the small stuff, he said, and launched into a pitch on how he could get noncoms going on Riot and Recreation to smuggle gemstones back for him. He said it was nuts to risk our butts for the kick alone and the simple thanks of a grateful nation. We were entitled to bennies from all the sweat and risk.

“Back in loosey-goosey Nam,” Miser said, “the whole fucking thing is to make it work for you.”

The Otter whined across the sky. I yawned and said, “Can you find out where the hell this windmill is going next? We’re cranking east. Cheo Reo’s south.”

Miser talked to the crew chief, the two shouting over the engine, then came back to me. “We’re going to the freakin’ coast,” he said. “Qui Nhon. Gotta pick up some priority stud.”

The VIP passenger was a full-bull colonel, a beet-red newbie just arrived. He loaded on and we climbed over the azure ocean before turning back inland high above the several hundred thousand citizens of Qui Nhon City toiling in the heat. A hundred supply ships stretched across the horizon, waiting their turns to unload. Some would wait months. I knew how they felt. The Otter wasn’t taking us anywhere soon either.

The crew chief beckoned us over. Cheo Reo, he promised, was next. For sure. Half an hour. Miser gave me a cynical glance. I occupied myself lightening my load of new issue. I jettisoned my shelter half, abandoned the tent stakes, tent cord, collapsed air mattress, and carrier, my gas mask and its pouch, the poncho, and six pairs of olive-drab underpants. Cutting the plates out of my flak jacket, I reduced it from nearly seven pounds to three, thought on it, and threw the flak vest away too, dumping everything into a wooden trash box in the back.

Columns of red dust rose behind long convoys of trucks and armor; the pilots spotted a wide dirt road off the major route and followed it south. No plumes. Aside from a lone bus or rickety truck, nothing. Everything bound for Cheo Reo arrived — like us — on a military air transport or helicopter, whether it was cases of Coke, grenades, or help in the event of an attack. Volcanic plains floated by, green jungles, and dry scrub. We followed the road and the lazy coils of a river looping across the flat land toward its junction with the larger Ea Pa and the province capital.

Cheo Reo. Finally. We landed and deplaned. The crew chief threw a bag of mail out after us. A spec-4 idled in a small truck. Farther on, a Vietnamese sentry box stood empty, its barrier pole vertical and unattended. No air-control tower, no other planes, no buildings, not so much as a forklift. Only a lone walk-in cargo container.

“You think that’s the f-ing arrivals terminal?” Miser said, jutting his little knob of a chin at the CONEX. “What do you think we did in a former life that Buddha sent us to this shit hole?”

The light was a stiletto after the plane’s dark innards. I made my way across the perforated steel planks that were latched together to make the runway. The sixty-five-pound planking was patched and worn, some of it blasted and jagged, the target of heavy bombardment.

“Well,” Miser said, “at least somebody thought enough of the place to shell the shit out of it.”

“Pilots must hate this strip,” I said, grateful we hadn’t blown a tire. A new asphalt runway was under construction, and dirt fill was being trucked in. A grader and backhoe belched diesel smoke as they worked.

A jeep sped toward us, churning dust, its windshield lying flat on the hood. The driver, red-haired and hatless, jumped out and greeted us with a genial smile without saluting. He had on threadbare stateside fatigues, no nametag or rank insignia. Freckles and golden-red stubble speckled his cheeks.

“Sir,” he said, gesturing for me to get in while he signed for a courier pouch and handed the clipboard back up to the crew chief.

Miser said, “Good day … Private, is it?”

“Yes, Sergeant. PFC Checkman. I clerk for the CO, Colonel Bennett.”

He hefted the mailbag and our duffels, threw them into the jeep, and slid behind the wheel as the Otter taxied away. Miser stepped up into the back, I took the front passenger seat, and we drove off at a leisurely pace.

“Which way should I look for the skyline?” Miser said.

Checkman’s forehead furrowed. “I can make a quick loop and show you.”

We passed by the Vietnamese guard post and rolled down a straight dirt strip, flat and wide. Across the airfield were the outskirts of the town: a scattering of tin-roofed shacks and two-story stucco buildings.

Miser scanned the horizon.

“Jesus H. Christ,” he said. “Who the fucking hell lives out here?”

“Montagnards,” Checkman replied. “Thousands of ’em. Jarai especially. Cheo Reo is the Jarai heartland.”

“It’s strange,” Miser said. “I never even heard of Phu Bon Province.”

Checkman beeped a goat out of the way. “It didn’t exist until recently. It was just Montagnard territory. Saigon decided it wanted a stronger government presence and made Cheo Reo a provincial capital.”

We turned left, past the MACV compound, and entered the metropolis.

“Cheo Reo’s a Montagnard clan name,” Checkman explained as we slowed. “The government forced them to rename it Hau Bon. Changed all the Yard names of villages and rivers to Vietnamese. But everyone still calls it Cheo Reo.”

The so-called capital was a shantytown. “The whole place is maybe six thousand Vietnamese,” Checkman said, stopping the vehicle. He slipped out from behind the wheel, courier pouch in hand. Kids immediately made a playground of the jeep as we walked away. Each child was immaculate, wearing clean if worn clothes. Unlike urban waifs, not one propositioned us for candy or cigarettes or tried to rent us his sister.

Nothing was paved. A hard-dirt street led to the market square, an open area circled with canvas-roofed stalls, goods spread on the shaded platforms beneath them. One dais held produce; another, stacks of dried fish. An old woman squatted beside a pyramid of rice. A butcher displayed the heads of monkeys and a small black deer the size of a Labrador. Two slaughtered ducks and a chicken hung upside down beside a goat and a couple of bats. A man bicycled past, holding an umbrella against the sun, and called out a melodic greeting to Checkman. Checkman answered in Vietnamese.

Nearby, a few barefoot women in sarongs and black shirts sat on their haunches beside carrier baskets in which they’d brought modest piles of tomatoes, onions, and peppers.

“Yards,” Checkman said. “Jarai. Don’t often see them in town. The Viets won’t let them hang around long.”

A small truck lumbered into the market area, a gorgeous dead tiger draped across its hood. A crowd gathered.

“Catch this,” Miser said. “Commercial opportunities in Cheo Reo.”

“You picturing clients on safari?” I said.

We went to touch the beast’s fur and huge teeth. A GI, passing on the other side of the road, shouted to Checkman: “Hey, Private Muff Diver! Careful that slope pussy don’t eat you.” He ducked away fast when he saw my captain’s bars.

Checkman interviewed the hunters and turned back to us. “They’re saying it walked into an ambush last night. I don’t know. Militias haven’t gone out patrolling at night in months, and it’s not all shot up. The pelt’s near perfect.” He ran a hand over the rich coat. “Must be worth a lot.”

Miser said, “Its choppers and guts are worth even more.”

“Right, right,” Checkman said, “local healers. I’ll show you the neighborhood pharmacy,” and he took us to a stall where a bear’s full hide, including the head, lay draped over one wooden barrel. A large preserved iguana was curled up on another. Glass jars on a plank held potent-looking elixirs with bees and less identifiable things floating in them. Checkman pointed out the bat’s-blood-and-rice-wine cocktail for tuberculosis beside jars of land leeches beckoning like miniature fingers.

A few stalls offered modest black-market booty, mostly stacks of green c-ration cans and field gear. Nothing like Saigon’s extravagant contraband. Along one end of the hard-packed square stood shops filled with cheap wares, a café, a photographer displaying large framed samples of hand-tinted portraits, the town barbershop, and an open-sided billiard hall. Pigpens and slop troughs immediately behind it gave off an acrid stench.

“Shit,” Miser croaked. “Who could play pool next to that?”

Checkman grinned. He shooed the kids out of the jeep and we got back in. We drove by some thatch huts roofed with metal sheets imprinted with beer-can logos and halted at the empty back side of town, a plain of dry, baked earth and scrub. We hadn’t passed a pagoda, a church, not so much as a gas station or streetlamp.

Checkman nodded toward the landscape. “End of city.”

Miser frowned. “Ass end of nowhere.”

Turning back, we passed some two-story stucco houses with second- floor balconies edged with Chinese filigrees. Checkman showed us a shop front screened in at ground level, sparsely furnished with a few low stools and tables on a concrete floor. It was a bar in front and a brothel in back.

“Homey as a garage,” Miser said. “What a place to get laid.”

Checkman pointed out a stucco building that looked Mediterranean. “The Korean medical team’s quarters and clinic. They treat Vietnamese. Two docs, three nurses. Dr. Towns’s dispensary is on the other side, down that alley.” He indicated a wide passage lined with shops.

“He European?” I said.

“She’s American.”

Miser’s head swiveled around. “An American woman, here?”

“Yep. She does the health-care thing for the Yards. There’s also a Christian Alliance missionary who runs a Yard leper colony a few klicks upriver. The Jarai never used to isolate their lepers but he talked them into it to reduce contagion. And there are two missionary couples: one here, the other in a Yard village way south.”

I said, “What’s the American headcount in the province?”

“Thirty Green Berets at the two Special Forces camps. Big one’s north of here, the other’s southeast. Also half a Special Forces team — that’s seven Berets — and two MACV officers at a district headquarters. An A-team may soon go in on a mountaintop at Buon Blech too.”

I said, “Thirty-nine. Is that it for our side?”

“Yeah, and the personnel here, and a dozen Army engineers bunking with us while they build the new airstrip.”

“What’ve we got locally?”

Checkman downshifted to first as we bounced along a water-eroded stretch of road. “You gentlemen just brought the compound’s total strength back to forty, sir.”

“What?” Miser exclaimed. “Did you say forty?”

“Fifty-two, counting the engineers on temporary duty.”

“How close is the nearest support?” I said. “You know. Firebases? Reinforcements?”

“Pleiku.” Checkman braked for a goat. “Like, fifty miles.”

Miser sighed. “Eighty klicks. So a plane with Gatling guns is the best we can expect if it hits the fucking fan.”

Checkman said, “The First Cav is straight north at An Khe, about forty miles. I don’t think we’re a top priority for them either.”

“South?”

“Empty for a couple of hundred miles until you get down around Saigon.”

“Crap,” Miser mumbled. “So eighty-nine Americans in a province the size of …?”

“Like, Delaware,” Checkman said, grinning. “We do have an ARVN battalion right across the road, and lots of strikers at the camps. Village militias too; most are Montagnard, a few are Vietnamese.”

“And that’s it for round-eyes?”

“Oh, the pinko French priest nobody ever sees. Likes to badmouth Americans and is supposed to be chummy with the VC. The Special Forces guys are always threatening to off him.”

“You think they’re kidding?” Miser teased.

“You never know with them, Sarge.” He downshifted. “There are two American USAID reps in the little compound next to ours. They just built a reinforced bunker for the province chief — under his quarters — and a tennis court on the edge of town. The prov chief ’s playing with the AID guys. Sometimes with Major Gidding.”

“Aren’t USAID people supposed to do useful shit like dig wells and put in public-address systems?” Miser said.

“The province chief wanted a pool table,” Checkman said, “he got a pool table. He wants a tennis court, he gets a tennis court. Everyone works at keeping the man happy. I’ll show you.” He veered left.

Miser’s chin rose in indignation. “No sewage pipes or running water, no streetlights. Wish I’d brought my fucking racket. I’d love to bust some USAID balls.”

We rolled up to the tennis court. A short, imperious Vietnamese in regulation whites was volleying with a lanky preppy in cutoffs and a T-shirt, his horn-rimmed glasses low on his beak.

“USAID taking on province chief Colonel Chinh,” said Checkman.

The court wasn’t much more than a concrete slab with no fencing. There was no net, just a clothesline strung across. A half-dozen Vietnamese troops acted as ball boys, and a dozen more formed a human backboard, though a horde of kids did most of the chasing of errant shots and passed balls. A plastic jug and water tumblers waited on a small table between two chairs draped with towels. A bowl of ice sat next to the tumblers.

A badly hit ball skipped past us, chased by a dozen boys. Miser took the opportunity to cadge a cube of ice to suck on.

“Would you mind keeping your hands out of the ice?” the USAID guy whined at him and pushed his eyeglasses higher on his aquiline nose. “That’s very unsanitary, what you’re doing.”

Miser gave him the fisheye and slowly spat the cube onto the court. The guy’s colleague glared at us from the sidelines. The USAID pair were familiar types. I’d have bet a week’s pay the onlooker with the short hair was ex-military and the one on the court a pedigreed preppy who was getting a leg up on a foreign-service career while keeping out of the draft. The young man returned to his serving position at the base line. A local came up and engaged Checkman in animated conversation.

“He says something’s going on down by the river that we should see.”

It was only a few hundred yards to the river’s edge and we covered it quickly in the jeep. Using scrub for handholds, we descended the steep bank. At the wide sweeping curve where the two rivers met, a huge waterlogged corpse lay beached on the sandy bank, face-up and nude, bloated arms outstretched like a sleepwalker’s, its sausage lips exaggerated and swollen like its erect penis. The tongue protruded from the giant round mouth. The eyes bulged. The scrotum was the size of a grapefruit. Judging from his short stature and sparse body hair, I guessed he wasn’t Caucasian.