Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

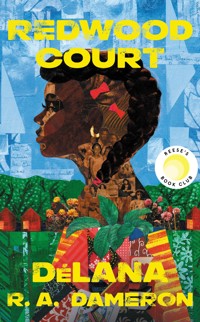

REESE'S BOOK CLUB PICK • A 'nuanced, brilliant' (Essence) debut about one unforgettable Southern Black family and its youngest daughter's coming of age in the 1990s. 'A triumph of a debut, Redwood Court is storytelling at its best: tender, vivid, and richly complicated' - Jacqueline Woodson, New York Times bestselling author of Red at the Bone Mika Tabor spends much of her time in the care of loved ones, listening to their stories and witnessing their struggles. On Redwood Court, a cul-de-sac in an all-Black working-class suburb of Columbia, South Carolina, she learns important lessons from those who raise her. With visceral clarity and powerful prose, award-winning poet DéLana R. A. Dameron reveals the devastation of being made to feel invisible and the transformative power of being seen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 450

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Redwood Court

SWIFT PRESS

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2024First published in the United States of America by Penguin Random House 2024

Copyright © DéLana R. A. Dameron 2024

The right of DéLana R. A. Dameron to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

‘Thirty-first Annual Chitlin Strut’ was originally published under a different title in Day One (2017) and ‘Work’ was originally published in Kweli Journal (2020).

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800754553eISBN: 9781800754560

“Listen: we were good,though we never believed it.”

—RITA DOVE, from Thomas & Beulah

Contents

Characters

Stories Everyone Knows and Tells

PART ONE

Redwood Court

Working My Way Back to You, Babe

How Do You Know Where You’re Going?

Cinderelly, Cinderelly

At the Cookout

All I Know Is Love Will Save the Day

When You Believe

Indian Summer: Lake Wateree

PART TWO

Thirty-first Annual Chitlin Strut

Rollin’ with My Homies

You Don’t Know What Love Is

Earthshine Mountain

Call a Spade a Spade

Silent Nights

First Blood

Work

Independent Women

Acknowledgments

Characters

LOUISE “WEESIE” BOLTON MOSBY (B. 1937): matriarch. She is the daughter of Lady and Mann Bolton of Thomson, Georgia, but has spent the majority of her life in Columbia, South Carolina. Weesie has an older brother, Peter, of Columbia, and a younger aunt, Hazel, of Chicago, IL. She marries Teeta in 1957.

JAMES “TEETA” MOSBY (B. 1934): patriarch, Korean War veteran. He is the son of Queen and Oscar Mosby of Green Sea, South Carolina. He and Weesie purchase the house at 154 Redwood Court in the late 1960s.

RHINA MOSBY TABOR (B. 1962): first child of Weesie and Teeta. She is born and raised in Columbia, South Carolina. She marries Thomas “Major” Tabor when she is seventeen, in 1979. They have two daughters, Sasha and Mika.

THOMAS “MAJOR” TABOR (B. 1959): first son of Annie and Thomas Tabor. He is raised in Charleston, South Carolina. Major has two older sisters, Jesse and Olive, and a younger brother, Griffin.

UNCLE JUNIOR (B. 1974): Rhina’s little brother by twelve years; Weesie’s surprise child, born when she is thirty-six. He has a daughter, Destiny.

SASHA “SISSY” (B. 1980): Major and Rhina’s first child, the first grandchild of the family. She is five years older than Mika and moves out right after high school to work and make a way for herself.

MIKA (B. 1985): second child of Major and Rhina. She is the baby of the family until Destiny is born in 1997, right before Mika turns twelve.

AUNT HAZEL: Weesie’s aunt, though born several years after Weesie.

DAISY: blood relative of Weesie on the Bolton side, living in Tampa, Florida.

DONNELL: Daisy’s grandson in Tampa. He is two years older than Mika.

REDWOOD COURT NEIGHBORS

REGGIE AND PEARL: Teeta and Weesie’s immediate neighbors to the left.

MRS. JACKSON: neighbor to Reggie and Pearl, two doors to the left of 154.

RUBY: Teeta and Weesie’s immediate neighbor to the right.

AUNT JESSE AND UNCLE QUINCY: Teeta and Weesie’s neighbors across the street; Major’s older half-sister and brother-in-law.

DOT: Aunt Jesse’s immediate neighbor to the right.

CALVIN: Aunt Jesse’s immediate neighbor to the left.

Stories Everyone Knows and Tells

My grandpa Teeta says I am the second and last daughter of Rhina, who is the only daughter of Weesie, who was the first daughter of Lady, who is the secret daughter of Big Sis, who was born to Sarah, who came from Esra, the adopted daughter of Ruth (who adopted her because Esra was a slave and was sold without her mama, but the story was Esra’s mama had thirteen children depending on who asked and depending on if you counted those unborn or born dead). Ruth had five children, three blood and two like Esra. Teeta says when we go back that far it’s hard to know who or what is what. That far back and it’s not a matter of blood relations so much as a matter of who brought up who? Who protected who? Who survived with who?

I am writing all of this down.

I tell him I have to draw a diagram for my history project and bring an artifact, one that traces my history all the way back to whatever country we emigrated from to come live in the United States. I know we didn’t emigrate like that, that is, of our own free will, but I ask him if he knows what countries at least we go back to.

“Baby, the way I see it, I don’t know if us Negroes get to answer that question in this life,” he said, pulling the cigarette from the corner of his mouth. I feel a way about his use of “Negroes,” because I thought the right term was “African American.” That’s what I’ve been taught to use. Teeta says ain’t nothing African about him but maybe his skin. The way they see him. To me, Negro sounds too close to the N-Word, but he says it’s clearer to him to define himself this way. Folks saying “Black” these days and meaning . . . not always American. He takes a sip of Sanka coffee I fixed just right. Just like he taught me: hot water, two sugars to three scoops of the bitter powder.

“How far back do you know we go?” I ask.

Jenny, who knows she’s Irish American, showed the class the family Bible where her blood relatives were documented back to the 1600s. Tucker, Dutch American, brought his grandmother’s doll with tiny wooden shoes, holding flowers that looked like teacups on the stems—tulips. Next week, I’m supposed to present whatever I bring to represent the country of my origin. I had asked Daddy to help me first, but he won’t no real help. Told me to just make a cowboy doll since he knows for sure he was born in Texas—what his birth certificate says. “That country, if they ask, is America,” he goes. I roll my eyes at his answer, but I also understand that it’s the only answer he has. I came to Teeta to see what he knows.

“We go back to Georgia for your grandma Weesie’s side, I guess.”

“And for you?”

“Sometimes I like to think we just emerged from the earth, like Adam. How we ’spose to go back.”

“Don’t you want to know more? Where we come from? Where we going?” I ask him. He squints at me how he does when he knows I’ll be on a list of questions he can’t answer. Teeta shrugs and says he don’t know if he wants to know more.

“What I know about who on this side of the ocean suffered what they did so that I could live the life I got is good enough for me. Waving somebody else’s flag ain’t gone give me more purpose than the one I waved in the wars I fought.” He pushes himself up a bit on the couch, but doesn’t sit upright fully. “How I see it, I either wallow in the unknowns that I ain’t never gone know, or I rest knowing my peoples over in Green Sea, South Carolina, is made of salt water and collards and oak-smoked ham.”

What am I made of? That’s not quite the question for the project, but it has arrived on my heart. How do I know what I am made of? I ask Teeta if we have anything written down anywhere—or if there was something I could bring in to satisfy the impossible-for-me assignment? What does it feel like to have a thing or things, like our own stories and books and whatever, to hold our histories that future generations can reference?

“Teeta, how do you think the future generations will know the lives we’ve lived?”

He sucks so hard on his cigarette you’d think he was pulling tobacco through it to the back of his throat.

“Baby, that’s your assignment, I guess. You the future generation,” he says. He leans his head back over the arm of the sofa, like how I watched a baby bird out my window calling for his mama, and puffs out Os into the still air of the den. “Whoever come after you, if that’s your plan, that’s the future, and whoever after that—that, too, the future.”

“But Teeta, who will tell them who we are?”

I’m thinking about how Missy has a book she could bring to class that is as big as the Britannicas in Uncle Junior’s room. Ms. Hunter showed us a book that was published and is sitting in the main branch library where her great-great-grandfather and all of the things—and people—he owned is listed.

What about us?

I didn’t realize my voice raised so high at the end of my question. Daddy’s cowboy-doll compromise meant I was coming to class saying I was just an American, nothing more. Nothing like my classmates who were American but also descendants of folks who chose to leave their known countries to be here. Teeta didn’t seem to understand me when I told him bringing in a handmade doll wasn’t the same as having something that people who lived years ago had touched and saved and put away and moved from country to country, house to house to house, until Timmy could bring it to class, and by that point—after all those generations and years and hands—it would be an artifact. That folks already had historical artifacts to bring in from home, that no one was making a thing to pack into their backpack.

He shrugged again.

“Someone made whatever it is them kids is branging in at some point to be passed down.”

I am worried if I don’t pass this assignment I’ll ruin my perfect grade in history and—like how everyone warns—my chance at college, ’cause it’ll be on my permanent record, and if I’m to be the first off to college, I have to pass every. Single. Class.

But this hurdle—the ocean between what’s asked of me and what I can answer.

. . .

“BABY, SURE, YOU GOT THIS PROJECT. DO IT. MAKE A FAMILY TREE branch or whatever. The lines I just told you about. I trust whatever you submit will be fine like it always is. But I guess I’m saying, maybe there’s a bigger something to go after that won’t never be finished—that you’ll make and make again and make some more, since you asking all these questions. You know, you sit at our feet all these hours and days, hearing us tell our tales. You have all these stories inside you—that’s what we have to pass on—all the stories everyone in our family knows and all the stories everyone in our family tells. You have the stories you’ve heard and the ones you’ve yet to hear. The ones you’ll live to tell someone else. That’s a gift that gives and gives and gives. You get to make it into something for tomorrow. You write ’em in your books and show everyone who we are.”

Part One

Redwood Court

It took thirty-two breaths to walk from Weesie’s front porch on the farm in Thomson, Georgia, to the county line, where the postman delivered their mail. Mostly bills, but sometimes a postcard or letter from her aunt Hazel who lived in “Chee-cago,” saying, Things are good, or Send money if you can, or Snow reached our windows for the third day in a row.

When Weesie stood on the porch, there weren’t any other houses for as far as the eye could see. There were other things she liked: being at the end of the singular road, so that if she heard the sherr and crunch of rocks under tires, that signaled someone was coming all this way intentionally to see about them; you don’t just pass by the end of a country road. And Weesie liked company. She felt her family didn’t get enough of it and wanted more. Even from the little glimpses of whatever life Aunt Hazel lived in Chicago, Weesie was jealous of her escape from farm life and its cyclical monotonies. That’s what happened with the younger generations. Yes, yes, Hazel was an “aunt,” because she was Lady’s little sister, but she was born a few years after Weesie. Because of the times and the place, Weesie, as young as she was, had to care about a harvest season, reaping and shelling the butter beans, cutting and drying the tobacco leaves. The long, drawnout days of it all.

She never saw it with her own eyes, thank God, but the white folks were closing in on her family’s little piece of farmland, increasing their public acts of violence in an attempt to recover their dignity, first post-Depression and now post–World War II. Nothing was ever enough. Weesie couldn’t go into town unaccompanied, and Mann (what everyone called her father) had to teach her how to hold a steak knife in her waistband—instructed use: for emergencies only. Mann himself had to make sure all of his steps were ordered just to go and pay a bill or get some nails from the hardware store, lest he, too, be disappeared, and the family read about some hunter finding his body in the woods an indeterminate amount of time later. Lady (what everyone called Weesie’s mama) scoffed: Won’t it the tail end of the first half of the twentieth century? Still, they felt the need to tiptoe around. Was there anywhere Black folks could go to be free like they said they were supposed to be?

It was the body found hanging from the light pole that had sealed their fate in Georgia. He was so gone—the maggots having done their maggoty thing—no one who saw the body knew who he was. Signature white-folk moves. Story was told that whoever he was had been caught stealing a stamp from the post office. Later, folks learned Jacob was trying to write a letter to his cousin in Detroit, to see if any money could be sent down because the harvest won’t as strong this June ’cause of the drought and the air was as dry as a sack of flour and even the drought-resistant crops gave up the ghosts and burnt. Could you believe it? That’s what prompted Lady to start packing. Mann won’t dare picture himself in the city or noplace where you could see into your neighbor’s house just looking out the window, so he said he didn’t know where she was going—whatever this place was called Columbia—but he won’t be going with them. He had his shotgun, he said. Let them white folks come.

A month later Lady, Weesie, and her brother Pete were in Columbia, South Carolina, in temporary housing. They chose Columbia because it was due east and the first “big city” they got to, and also because some other family had made their way there in 1946 after the war dust settled. It had taken Lady two years to make the leap herself. Compared to Thomson, there were so many houses and buildings with multiple stories, you had to look up where you were walking to know where you were going. Everything in Columbia was hard roads and manicured trees. Folks were closer together; it was hard to see where you could go and where you couldn’t. Everywhere signs were shouting COLORED ONLY / WHITES ONLY and so forth. In Thomson, you knew on one side of the railroad tracks was for the whites and on the other side of the railroad tracks, down the road and around the corner, was for Blacks.

Here, you’d have a department store for whites, and across the street a department store for Blacks. When Lady got a job at Woolworth’s and needed something for the house, she had to clock out, walk across the street, and pay full price for the tea towels or frying pan. Then the white folks decided they wanted downtown to themselves, so she had to drive across town to buy the things she sold ten hours a day—only those items were WHITES-ONLY items; she had to go use up her gas in search of the Black ones.

For Weesie, though, it all felt shiny, different. The front-lawn grasses were watered so much that it was too green to look real. Even the brick rows of two-room residences felt like a luxury: the bathroom was inside the building, even if you had to share with a neighbor. You knew you had arrived if you had one of those plug-in stoves to get cooking, and maybe best of all, some of the houses were hooked up so you turned a knob over the washtub and the water was hot. Even though it came out brown first and they had to run it ’til it ran clear, it was hot, automatic water.

So this was heaven.

WEESIE LOVED TO TELL THE STORY OF HOW SHE’D FIRST MET Teeta at the collard-green stand. She’d say, “At the collard green in nineteen and fifty-two.” Teeta was unloading the truck early one Saturday morning and Weesie was coming for her bundles for Sunday supper. Teeta was pulling out a patch of mustard greens just as Weesie was walking up, and before he could put the bundle on the wood table, Weesie scooped them up.

“These my favorite. They sweeter than collards. Don’t need the sugar to take out the bite,” Weesie said. She smiled at him. Teeta tipped his hat and kept unloading.

If Teeta were there when Weesie was reliving those days, he’d say something about how he didn’t even know what Weesie was talking about. Greens is greens. He was just trying to make his five dollars for the day, so he could go to the pool hall later that evening before heading back to Green Sea on the coast until the next weekend. It won’t until she kept coming back and kept trying to grab his hands and the mustards that he started to think something. Finally, one day she asked his name. “Teeta,” he said, smiling. By then, Weesie had decided she would always be the one to make the collard run every Saturday, and every Saturday like clockwork, Teeta was there.

Until one day he wasn’t.

When word got around that they were requesting more men to support in Korea, Pete suited up for the navy. Lady did some scheme with the other Negro women managing the enlistment paperwork and her baby Pete came back beaming: he could stay stateside and clean the ships and manage the goings on in the shipyard. He only had to go an hour and a half away. This was relief enough for Lady and Weesie, though it felt eerily familiar to the tension in the air in Thomson just before they fled: every day, another Black man raptured into the sky. The third Saturday came and went without any sighting of Teeta. And then a new gentleman arrived managing the collard-green stand. He was older, probably not draft age—Weesie could tell because of all the grays and the ways his jowls hung low like Mann’s did the older he got. She asked the collard-stand owner where the young gentleman Teeta was these days and he said only, “They shipped him off.”

The sweet potatoes in her hand just about fell straight to the ground.

OF COURSE, WHOLE LIVES WERE LIVED IN THE YEARS BEFORE Weesie and Teeta got married. But when Weesie tells it, it’s as if her life started when Teeta came back to Columbia five years after they first met and looked for her at the collard stand. Truth was the army shipped Teeta back to Green Sea, where he floundered for some time trying to land but couldn’t find a drop a work and didn’t want to necessarily go back to the fields. He yearned to get back to the big city.

Teeta couldn’t remember exactly what Weesie had looked like, only that there was a buttered-cornbread-colored young woman who always bought two collard bunches and one mustard, and took her time picking through the largest and roundest sweet potatoes. When he finally wandered his way back to Columbia, every Saturday he’d roll off his army brother’s mother’s couch and say he was going to work. It was something like work. He would go and help the elderly carry a week’s worth of fresh vegetables to their trunks and get a few coins in thanks. He would walk up the road to the Winn-Dixie and offer to help bale the empty vegetable boxes, sweep—anything. Sure, he was getting whatever thanks the service offered for years of his life and pieces of his brain—and he gave up most of that for his share of the rent, for a few cans of Schlitz or Olde English, his ration of Marlboro cigarettes from the Shamrock Corner Store, and a few rounds of pool at night. It was when that routine got old and folks kept asking when he would settle down that he remembered the woman he had wanted to get to know before he was sent off to the war. Just when he had gotten the nerve to ask her to go steady, he turned eighteen and immediately was served papers. He figured it won’t no use starting something only to go off and die in Korea and leave her broken.

But he’d survived and found himself in Columbia again, and once he got his sea legs under him, he thought, once he stopped hearing the rattle of machine guns at night even above the whirr of the floor fan, once he could go outside and see a high-yellow person walk in front of him and know they won’t the enemy, then he could consider creating the life he’d wanted to build in the before. He had tried with a few women and failed. So he went to the collard-green stand and he returned and returned again and again—until, eventually, there she was.

As Teeta tells the story, Weesie was fussing, as usual, about the quality of the greens to the old man, insisting he look for a better mustard bunch, just one, and she already had with her the round sweet potatoes and two collards. They had exchanged names all those years ago, but he couldn’t remember hers. He had, however, remembered to wear his best shirt, like he did every Saturday, hoping their timing would align.

Weesie takes over telling the story at this point, and always has to say that Teeta had come up a little too close behind her and she had reached for her steak knife that she still carried because white folks was crazy, especially as the rumblings of civil rights had started to make their way into town.

Teeta always shakes his head, remembering her reaching behind her back. He held his hands up and just said, “It’s me, Teeta. I used to give you the best mustards right here.”

And then once Weesie realized it was the man with the sweet greens, they laughed, and that exact day they went for a ride in her car. It was when Teeta tried to get too fresh that she stopped the car in the middle of nowhere and kicked him out.

Weesie would shrug and wink at Teeta. He’d let out a short huff, still in disbelief.

“I had to hitchhike back to our side of town,” Teeta would say, smirking, shaking his head.

Three months after they met again, they were married and moved in with Weesie’s brother, Pete, and his new bride, Viola, over near downtown Columbia, not far from the main Greyhound bus station. Two young couples with still-war-weary men at the beginning of their lives.

It was all a blur if you asked Weesie to make sense of it, to map out how four adults and five kids all did it. It was as if the house unfolded each time a new baby came, and there was room for everyone. Even if it felt like how she imagined her aunt Hazel’s life in Chicago might be—busting at the seams with bodies crammed in each corner—she rested in the belief that it would be temporary, because she had set her sights on a new subdivision called Newcastle that was coming along on the other side of town in what folks called “the suburbs.” Newcastle was an all-Negro residential neighborhood with three- and four-bedroom ranchstyle brick houses with good-sized lots. Enough for a garden and more. If they just saved up and made the right moves at the right time—God’s timing—they could have a new house, too. And word was, soon there would be a groundbreaking ceremony for a shopping complex around the corner, and a whole retail corridor just down the road.

When the street names started to be mapped out and signposts pounded into the ground, open houses popped up every Saturday and Sunday, competing with weekend shopping. If you were one of the early ones, you could choose your plot and wait for the construction and simply move in. Just like that. Weesie sacrificed a Saturday at the flea to go to the construction sites and get a feel for what she really wanted. She tried several of the names on for size: Weldwood Court, Newcastle Drive, Cool-stream, Redwood Court, Devoe, and so on. Then she tried them in order of how you came into the subdivision, just off Shakespeare Road: Carlton Drive, Jonquil Street, Carnaby Court, Redwood Court, Newcastle Drive.

Weesie loved Redwood Court because she liked the way it sounded in her mouth, and depending on who she said it to, it could sound like a Columbian (and not country Georgian) accent, though she was still known to dip down her vowels even lower just for “Court” if she said it too quickly, and couldn’t help that she added a half syllable. “Coat-eh.” She had to think to say “cut” to get it to sound right. It didn’t matter; when she found her house, she loved to say it out loud: “One fifty-four Redwood Court.” Her soon-to-be new address. On a cul-de-sac with nineteen other houses—the most houses she’d ever lived close to.

Even though they nearly all went up the same year, 1968, this was back when there were craftsmen, and while everyone started with a bath and a half, a carport (“car pote”), three bedrooms, and a back patio, there was a uniqueness that showed care. You weren’t just choosing any-number ranch house in Newcastle. You were choosing your lifestyle, your retirement, a part of your family.

One fifty-four Redwood Court was in the middle of the culde-sac on the right side, the east side. The top of the court faced due north, so if Weesie stood in her carport and looked right, she could see all the houses that rounded it out. Looking left, she could see the stop sign. The only other house that had nearly the same view was across the street; but they didn’t have a magnolia, and they definitely didn’t have a eucalyptus tree or a raised concrete patio that Teeta started sketching plans for an addition to even before they sat with the bank. Most owners on the Court, they learned, had kids or were planning to, or grands, and that made Weesie and Teeta feel not so bad about their six-year-old daughter, Rhina—alone, once they left Pete and Viola’s house and moved into paradise.

ONE OF THE THINGS WEESIE BROUGHT TO REDWOOD COURT that had been instilled in her in Georgia was an overwhelming sense that where systems fail, people prevail. Maybe Lady said that phrase first, having gotten it from someone else when they had all chipped in a dollar to help pay for the burials of loved ones. At Redwood Court, Weesie saw it happen day in and day out: people cultivating their own bounties to share with one another. Reggie, their neighbor to the left, grew squash and cucumbers; Teeta set up with tomatoes, strawberries, and bell peppers; and Ruby, to their immediate right, had the tallest pecan tree Weesie had ever seen in her life—and in Georgia, she had seen some pretty tall ones. All of them born just after the Depression, which is to say all of them raised by parents grown enough to think they wouldn’t make it through, yet found ways to survive: being strategic about where you might invest what little you did have, and always, always understanding the basic truth of living with less, which is that the sum of parts could make a whole.

If Weesie didn’t know any better, it was like Redwood Court was waiting for her—the final swipe of paint on the Sistine Chapel. What men ruled at the church—deacons and trustees and so on—Weesie and now her neighbors Ruby and Dot had in Redwood Court: a kingdom. And so they organized cookouts hosted by different houses, and yard sales to make a few dollars. It was always funny to watch a trinket move from house to house to house until, finally, Weesie would catch it at the flea market in Lexington and watch a white lady pay five dollars for a mammy ceramic or some such.

Out of everyone who had found their way to the Court, no one had grown up in a real subdivision, so there was a level of improvisation when it came to establishing codes and conducts. Having the backbone of church upbringings certainly helped in that regard. For those folks on hard times, Weesie had gathered all the ladies of the houses and offered to be block captain for the benevolence fund, a kitty for folks in the cul-de-sac who had a specific need that they felt an influx of cash could support. Armed with her manila folder with ledger lines, she went door to door to collect any change, really, to purchase a bouquet for someone who had died, or to be able to hand over an envelope of the Court’s “love offering.”

Weesie knew the need mostly because she made it a point to make people her business. After a few years in the classroom as a primary school teacher’s aide, she understood that she liked being of service to folks, but also relished the exchange that happens in the small moments. As an aide to Miss Hinton, a strict disciplinarian, Weesie found her special time with the students to be between lessons—during quiet-work moments, at lunch, before and after school. It was Weesie’s turn to ask questions then. She loved getting to know the children and learning their stories, mostly because they gave her so much information.

One afternoon during a shared lunch with Vera, a student she helped often during class, Weesie learned that the girl once went into the candy store looking for a few pieces of penny candy and couldn’t figure out why the clerk lied and said he didn’t have any.

“Was it a white man?” Weesie had asked, knowing where this story might be going. Vera nodded.

In the store Vera had pointed to the candy she wanted—the ones she could afford and also the ones that happened to be her favorite—and asked, please, for two strawberry-flavored pieces. The clerk with the candy who said he ain’t had none then grabbed his ruler and brought it down at a hard angle on the finger Vera pointed in the direction of her desire. The clerk had moved so quickly, Vera said that it won’t until the brightness in her eyes had faded from the shock and pain did she realize she was bleeding.

“Don’t you have no manners, girl?” Vera said the clerk had asked. Weesie reached for Vera’s hand and rubbed the child’s fingertip, where she could still see the faint marks of a scar.

“And then, when I got home, Mama took a switch to me. I was bleeding and crying and trying to tell her how this man lied ’bout not having no candy and she whippin’ me, talking ’bout I shoulda known better than to go to that store. But it was a candy store.”

Weesie had thought about Miss Hinton and her style of teaching. If she had been a half shade lighter, she coulda passed, and maybe that’s where her resentment came from? Every lesson, to accentuate her point, Miss Hinton tapped the sharp corner of a yardstick on the blackboard. Or whenever the students were too rowdy, she’d whack the edge of her desk and the noise would strike its way to the back of the class, where Vera was with Weesie, freezing up. Weesie understood why Vera had required that each lesson be repeated slowly, whispered in her ear like a lullaby. Moments like these made clearer to her a new path: cosmetology.

When parents and neighbors in Redwood Court understood that Weesie was gentle, even with the broken ones, and could whisper a child still even with a hot-iron comb a millimeter from their ears, they came two-by-two to the back door of the house each Sunday after supper. Weesie didn’t mind—she was making a bit extra above her teacher’s aide wages, and getting to know the neighborhood children who liked to play with Rhina. Plus, in between the sizzling pulls of the hot comb turning kinky hair straight, she could enjoy one of her favorite pastimes: gossip.

One time, Dot had brought over her girl even though Weesie had just pressed her hair the week before. Dot had all but shoved the child into Weesie’s seat in the middle of the kitchen and started getting to her story. How Buddy had been taking to drink too much these days and it was starting to impact their marriage.

“You know, I make a bit extra cleaning those houses by the lake. I put it in my cigarette case ’cause I figure Buddy has his own, and I mine, so won’t no use in being up in my case. I come in from sweeping the carport and I see it open on the counter. I don’t leave it open; that’s how they get stale. All but three dollars is gone. I had saved almost ten dollars, Weesie.”

Weesie had just been brushing the child’s hair, helping smooth out the few strands that were starting to loosen back into a curl. She couldn’t put more heat on it so soon or she’d risk damage.

“Did you ask him ’bout it?” Weesie took a few pats of blue hair grease off the back of her hand and smoothed the girl’s edges.

“Last I asked him any question, if it was a bad day, he’d take it to be a whole accusation of his character. It’s like he’d blink and his eyes would look into the distance, through me, like he was back in Korea and I was the enemy.”

“Yeah. Teeta goes there, too, sometimes. Once he was so deep in it, I had to throw a glass a water on him,” Weesie said. She had finished the girl’s hair.

“You dumped water on him like he was a cat?” the girl asked.

“I guess I did, baby,” Weesie said, chuckling while raising her eyebrows at Dot. The next time Dot came off schedule, she was alone.

Folks kept coming, even before she was official with her license, spending their own hard-saved dollars for her hair work. The added bonus of getting to know folks, of being counsel or sister-friend, made the hours on her feet more joyful than a whole week in the classroom. It was how Weesie knew Mrs. Jackson’s husband had gone in for a biopsy, how she knew that the first house on the right when you get to the bubble of the cul-de-sac had a kid who liked to start trouble (one day for the heck of it he set the bathroom curtains aflame). And how she could keep tabs a bit on Teeta without confronting him directly—folks would come into her kitchen and tell her stories, or more often lay they troubles down, as the song goes.

So, when Weesie heard (though not from them) that Johnny and June, also at the top but on the left of Redwood Court, fell behind on their mortgage and could face their house being taken away, and then Rhina would lose her best friend, Weesie got to thinking of what she could do—what Redwood Court could do—to keep them in their home. And she thought that a cookout and fish fry could be the perfect answer.

Armed with her manila folder, Weesie went up and down Redwood Court, skipping Johnny and June’s, for a two-dollar investment from each house to buy supplies for the fundraiser. Some folks required a bit more convincing because this seemed like a bigger task—saving a house—than, say, sending a bouquet or a one-time cash infusion.

“Don’t God tell us to lean on his understanding?” Weesie would start her story at the door. She’d refuse entry by waving the manila folder—showing her visit was a business one, not a social one. “Just think: two dollars today can help us make plates for all of Newcastle. They’d come, get a fish plate or a burger sandwich. We can save some for the Court kitty for future big events like this. If you give today, you can get your plate free on Saturday. And we can keep Johnny and June as neighbors. Can you imagine anyone else living there with those azalea bushes? Being in community with us?”

Most times it worked. Except with Clara, down near the stop sign, who always kept a rotation of rottweilers in her gated front yard, and so Weesie had to position herself in front of her screen door just so and holler “Clay-rah” just above the barking to get Clara out the house to meet Weesie at the fence. Clara lived alone and never said why, but sometimes Weesie could get her to open up. Today, though, Clara was one of the holdouts, and Weesie had to get her arsenal of tools to convince her to participate. It was important that Weesie be able to report to the neighbor in need that 100 percent of Redwood Court had made the gesture. Clara claimed she didn’t eat fish plates, even though Weesie knew it was a lie. She came back every Saturday morning from the river with a bucket and her poles and smelled of burnt oil in the afternoon. Weesie said there’d be something for her there, though; she’d make sure of it.

“Besides, remember when you had to get your gate fixed because your Prince kept jumping it?”

Clara nodded.

“I would never tell folks’ business like this, you know, but June and Johnny was the first to chip in, and the most. ’Bout dumped the whole of their wallets into the kitty. Johnny went with Teeta to get the materials, and it was Johnny’s post digger that got it done.”

Weesie tapped the top of the fence post.

At the cookout that Saturday, Weesie told anyone who bought a plate that Redwood Court, all of them, took care of they own.

TEETA CAME IN FROM A FULL DAY OF YARD WORK AND CATCH-ing up with Reggie over the back fence. He’d enclosed the raised patio for an informal den space not long after they’d moved into 154 Redwood Court and got to working on a screened enclosure just off the side of the den. It would have room for off-season clothes storage, another full ice box where he kept what he called his “refreshers,” and the extra tables and chairs that they pulled out whenever Weesie had it in her to host a cookout on the warm holidays, like Easter, or Memorial Day, or the Fourth, or Labor Day, in that order. Teeta especially loved that time of holidays strung along like tinsel because he could mask the increasing numbers of Olde Englishes he was drinking every weekend. Weesie saw it, of course, but chose not to make a deal out of it. She knew it was working in the morgue at Bull Street state hospital—bottling up bad brains and things, on top of the wounds from Korea—that made Teeta think he had to cling to drink like a totem. Like it would steady his shaking hands. Won’t no use fighting the truth with folks not ready to see it.

Like Mrs. Jackson, who thought she could muscle her way through her husband’s cancer diagnosis when sugar diabetes was making its way to her limbs. Weesie had called out to her one day when she was driving down the street, headed home. Mrs. Jack-son lifted her hand and let it fall. Weesie took it to be something like shoo-flying her away and so started on her way inside the house. From the kitchen door, if she leaned just right, Weesie could see Mrs. Jackson’s brown-and-blue station wagon in the driveway. They had a garage with a working door, and Weesie saw inside one day—it was packed so tight with boxes, she understood why the Jacksons never used it.

When Mr. Jackson went to the hospital the last time, Weesie watched the ambulance carry him out, and watched again when they brought him back. It took four men to lift him and his oxygen tank and stretcher up the three steps of the front porch. Because his black sports car was also parked in the driveway close to the house, it meant that Mrs. Jackson had to park behind it and walk almost from all the way at the yard curb to her door, some twenty-five or thirty steps, depending on how much her sugar was weighing on her gait.

“Teeta, she shuffling now. Mrs. Jackson. Look!” Weesie said, leaning further out the kitchen door. Teeta had come into the dining room rustling for a snack.

Weesie started dialing Ruby, but Ruby won’t able to see past her yard, Weesie’s yard, and Reggie’s house, so she hung up to dial Dot directly. She was ’cross the street.

“Hey, Dot. Weesie. Yeh, fine. You know. Same-o. Say, can you see Mrs. Jackson out your window? Yeh. I figured she’d still be trying to get inside.” Weesie covered the receiver and turned to Teeta, perched on the island, chewing on whatever he found—saltines, maybe. “Dot saying she bent over like the midmonth moon.”

Teeta shrugged, nodded.

“Yeh. When I saw her, she was leaning on the car for support, but I guess without it . . .” She trailed off. “Hold on, Dot.” Weesie handed the phone to Teeta to hold while she rustled around in the back porch. Teeta almost held the phone to his ear, as if to say his greetings. But he cleared his throat of the crumbling crackers and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. Weesie emerged a few moments later with a set of crutches she kept from her day job in the salon at Crafts-Farrow State Hospital—one of the patients had started so fast from the sudden rush of warm water Weesie had put against her scalp that she punched her in the stomach. The force knocked the wind out of Weesie and she slipped and fell while still squeezing the sprayer. When she got up to chase after the patient-client, Weesie slipped back onto the floor with her foot directly under her butt.

“OK, Dot, I’m back. Wanted to see if I kept the crutches from when Dr. Johnson said I sprained my ankle. Yeh. They super short, so you can save your armpit. The first set I sent back ’cause I was so sore. He said to set it lower, and you know I had tried that! Anyways, maybe Mrs. Jackson can use them.”

Teeta sucked his teeth. “I don’t know why you keep trying with her, Weesie,” he said. She rolled her eyes and leaned the crutches against the fridge, then reached for the counter cloth to wipe the stove—her busywork while on the phone.

“Maybe I’ll take ’em tomorrow. Yeh. Yeh.”

She stopped wiping.

“Teeta. Dot says Mrs. Jackson cain’t even lift her legs enough to get up the stairs! We should go over.” Weesie hung up the phone and contemplated taking the crutches over. It was already going to be a task to get Mrs. Jackson to accept any help, much less hand-me-down items that screamed with every click-clickclack and foot shuffle just how much help was needed. Maybe if introduced all at once, she wouldn’t be able to choose what to deny. Weesie left the crutches this time, and before she could get halfway across Reggie’s yard, she heard Mrs. Jackson’s voice, as raspy as Sunday newspaper coupons crinkling open.

“I’m alright, Louise.”

Mrs. Jackson was truly the only person to call her by her government name other than the pastor at her wedding ceremony in 1957. Even he had to catch himself when it came time for the couple to recite their vows. But when Mrs. Jackson moved to Redwood Court, Weesie brought her a basket of oranges and a few sprigs of her homegrown eucalyptus as a welcome gift. Mrs. Jack-son half-smiled and didn’t let her in. Weesie welcomed her anyways with her usual “Everyone calls me Weesie, so please—”

“I prefer we use real names,” Mrs. Jackson interrupted. Caught off guard, Weesie said her name like she was spelling it out for a bill collector. “Louise Mosby. Married to James Mosby.” Won’t no need in saying Teeta either. “We over at 154, two doors down.” Mrs. Jackson nodded.

“Nice to meet you, Louise. We should get on to unpacking. Thanks again.”

Weesie knew when to push her luck and that day wasn’t one of them. When she heard the same tenor from the steps of the front porch, where Mrs. Jackson had paused in her journey from car to house, Weesie slowed down, sure, but kept coming. Mrs. Jackson must have wagered that won’t no use sending her away, and you couldn’t, anyways, once Weesie had it in her to do something.

“I’m just coming to see ’bout Mr. Jackson. Must been weeks since sunshine touched his forehead, huh?” She tried to deflect while glancing across the street. Dot was standing in the screen door. Oh, Dot. Just showing all the cards.

“I said I’m fine, Louise. You can call off the hunt,” Mrs. Jack-son said while still doubled over, pointing her chin in Dot’s direction. Dot waved.

Weesie reached down with her hands under Mrs. Jackson’s armpits to straighten her up, like she did for Mrs. Cook, the white lady whose house she went to after work and some weekends and sat with sometimes while Mrs. Cook’s grown children did grown-children things. Mrs. Cook, who was old but could still do much, like use the pot, only needed Weesie’s help to get up and down out of bed or her sitting chair. Weesie grunted as she lifted Mrs. Jackson from her knees.

“My mama tried to hide it for so long, too,” Weesie said. Mrs. Jackson was only protesting in theory. Weesie knew a body in protest and a body surrendered. “When sugar diabetes got to her feet, it was harder to hide. Your body gives it away in other ways: how the back curves to offset the balance we lose, the way our ankles expand with water and look like tree stumps.”

Mrs. Jackson sighed.

“Lift the left foot now, like that,” Weesie coached. “I got you. Yep. Now the right. We can take as long as it needs to take. Were you out getting groceries? Do you need me to brang them in?”

“The Coke prolly hot and ice melted now,” Mrs. Jackson said, purring. “That’s all he wanted: a ice Coke and hamburger from McDonald’s.”

“We’ll take care of it,” Weesie said and carried her inside.

Working My Way Back to You, Babe

Weesie

It was when the first occupants of the house across the street from us came and left and I had not the mouse-crumb clue about who they were or where they came from or where they was going that I decided whoever was next to take the for sale sign down and set they roots on Redwood Court would be so known. I wanted them to come on in and feel like family.

“Don’t go over there smothering them like you won’t to do,” Teeta warned me like he won’t to do.

I was trying to lean as far as I could out the kitchen door without tipping into the carport. “Shush, Teeta,” I tell him, “I’m just looking. They got a big fat bulldog. He was waddling behind two boys. I’m just trying to see if the woman white, though. She so bright. Shush now so I can see!”

I do what I have to do to get the information I need. I call Dot.

“She white? She look it.”

Dot laughs. “Who white gone move here?”

“Someone who marry a man the color of my Lady’s seasoned skillet and trusts to have his children. You got any word?”

According to Dot, who, with Buddy, introduced herself on the first day, Jesse has lived a life of social work and church service. Yes, she’s Black. That’s how she call herself, anyhow. When Quincy joined up into the service, she became a housewife while he was sent over to war in the final days of Vietnam to help sort out who was going home, in what condition, and where and when. Soon’s it looked like Saigon would fall, he hopped on a plane back to the States as the country was burning, then went straight to his staff sergeant’s office to demand release. He used every penny saved for his own little piece of Redwood Court.

Dot say Jesse from the low country. Them folks sound like they got a mouth full of sweet grass. Ain’t that funny? I’m from Georgia, yet when I finally marched my tail over to speak to her, I had to squint to be able to understand. You know how my mouth go and I worry I’ll get caught up saying something I ain’t mean to say so I stopped trying and chatted up mostly with Quincy and relegated Jesse to a wave—but not a chat—from the carport.

Teeta reminded me of how them first residents was so disconnected from us all that they left the yard looking like a landfill. Won’t I trying not to re-create history? I say, “I tried being neighbor-like!” But I just couldn’t fake it.

The stories started flowing around the neighborhood. Folks whispering they theories on a phone tree: Why is Weesie so distant to the wife? She have a thing for the husband?

Dot told me what was going round.

I said, “What I need another service man in my bed for?” I told her I already got one with episodes that come and go like the coastal tides—’specially after Junior come, and so late into our thirties. It was like Teeta just come back from Korea again. My hands was too full with a toddler ripping and roaring through the nights and waiting to know if Teeta gone come back from the pool hall or juke joint or be picked up by the police—or worse—for me to be trying to have a secret relationship!

Upon hearing the absolutely untrue gossip, I brought some biscuits over to confront it directly. What did pastor say? Seek the higher ground. Ain’t that something? You sit in church all your Sundays thinking a sermon won’t about you at all, but ends up, it is?

So, in broad daylight, I deliver the biscuits—just in case anyone want to look out they window. I know how they do. Do my knock. You know it: the triple-double knock. Tap-tap-tap. Tap-tap.

I was nervous. When Jesse opened the door, I showed her the biscuits and told her what they were. (Don’t ask. I know folk eat biscuits in the low country.) She says, “I know,” but it sounded like “a new”—low, guttural. Atlantic salt spray making her tongue sticky. I chuckled only when I’m telling Teeta later. At the door, I was a perfect neighbor.

“This how you in this predic’ment,” Teeta says. He always say I’m picking at people who ain’t got nothing to do with me.

I shrug.

But anyways, she mumbled thanks under her breath and reached for the biscuits and excused herself.

I report to Ruby that she ain’t even let me see more than the corner of her kitchen countertop, and that was only ’cause I was leaning. Hard. I ask Ruby if she think Jesse got something to hide and started my recap down my phone tree, calling Dot next.

Dot ain’t have any new information, so I tell her I’ll try her back after church this Sunday coming. While the phone ringing, I set up the last pots for Sunday’s supper and let the cabbage simmer to melt while starting my post-church rounds.

“Glad I had my handkerchief ready for Willie Mae when the spirit caught her and she fell like one of them thousand-year oaks,” I said, ashing my cigarette and ignoring Teeta’s eye rolls, flapping my hand like a hummingbird to send him outside if he ain’t wanna hear my stories.

“Ain’t you just left ’em? Ain’t y’all saw and heard the same things?”

I tell him to let me have my Sunday like I like it. Full of gospel and gossip. He went outside.