7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

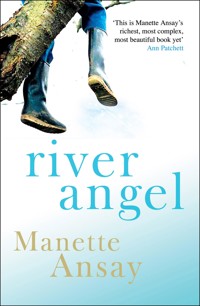

Many citizens of Ambient, Wisconsin, believe the old tales of an angel living in the Onion River that runs through the heart of their town. So when Gabriel Carpenter vanishes one night at the river's edge after being accosted by troublesome teenagers, he is presumed drowned. Yet the teenagers all tell a different and conflicting story, and when Gabriels lifeless body is found in a barn a mile away no one in this quiet Midwestern community can agree whether a miracle or a hoax has occurred. But as the story spreads, and curious tourists overrun the town - some skeptical, others reverent, still others angling for financial gain - one fact becomes certain beyond any doubt: life here will never be the same.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

River Angel

Manette Ansay

This book is dedicated to Stephen Hall Smith

And Jesus said unto them … If ye have faith as a grain of mustard seed, ye shall say unto this mountain, Remove hence to yonder place; and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible unto you.

—MATTHEW 17:20

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Coda

About the Author

Copyright

Author’s Note

River Angel is a work of fiction, the best way I’ve found to tell the truth. It is less the story of an individual than the history of a community; it is less about what did or did not happen in a town I have chosen to call Ambient than it is about the ways in which we try to make sense of a world that doesn’t.

In April 1991, in a little Wisconsin town about a hundred miles southwest of the town where I grew up, a misfit boy was kidnapped by a group of high school kids who, later, would testify they’d merely meant to frighten him, to drive him around for a while. Somehow they ended up at the river, whooping and hollering on a two-lane bridge. Somehow the boy was shoved, he jumped, he slipped—accounts vary—into the icy water. The kids told police that they never heard a splash; one reported seeing a brilliant flash of light. (Several people in the area witnessed a similar light, while others recalled hearing something “kind of like thunder.”) All night, volunteers walked the river’s edge, but it was dawn before the body was found in a barn a good mile from the bridge. Investigators constructed this unlikely scenario: The boy had drifted downstream, crawled out of the water, climbed up the slick embankment, and crossed a snow-dusted pea field. But if that was the case, then where were the footprints? The evidence of his shivering scramble up the embankment? And how could he have survived the cold long enough to make it that far?

The owner of the barn had been the one to discover the body, and she said the boy’s cheeks were rosy, his skin warm to the touch. A sweet smell hung in the air. “It was,” she said, “as if he were just sleeping.” And then she told police she believed an angel had carried him there.

For years, it had been said that an angel lived in the river. Residents flipped coins into the water for luck, and a few claimed they had seen the angel, or known someone who’d seen it. The historical society downtown had a farmwife’s journal, dated 1898, in which a woman described how an angel had rescued her family from a flood. Now, as the story of the boy’s death spread, more people came forward with accounts of strange things that had happened on that night. Dogs had barked without ceasing till dawn; livestock broke free of padlocked barns. Someone’s child crayoned a bridge and, above it, a wide-winged tapioca angel. Several people reported dream visitations by the dead. There were stories about the boy himself—that he frequently prayed in public places, that he never once raised his hand against another, that a childless woman conceived after showing him one small act of kindness.

Though both church and state investigators eventually deemed all evidence unsubstantiated, money was raised to build a shrine on the spot where the boy’s body was found. I have been to the River Angel shrine, and to others. I have traveled to places as unlikely as Cullman, Alabama, and as breathtaking as Chimayo, New Mexico. I leaf through the gift shop books about angels, books about miracles, books filled with personal testimonies. Books in which supernatural events rescue ordinary people from the effects of a world that is becoming increasingly violent, dangerous, complex. Though I myself am not a believer, I understand the desire to believe. I live every day with the weight of that desire.

Ultimately, I have found it is meaningless to hold the yardstick of fact against the complexities of the human heart. Reality simply isn’t large enough to hold us. And so the sky becomes a gateway to the heavens. Death is not an end but a beginning. A child crossing a pea field into the indifferent, inevitable darkness may be reborn, raised up by our longing into light.

Holly’s Field, Wisconsin

Acknowledgements

Thank you, Saint Martha, for favors granted. The following prayer is to be said for nine consecutive Tuesdays: Saint Martha, I resort to your protection and faith. Comfort me in all my difficulties and, through the great favor you enjoy in the house of my savior, intercede for me and my family. (Say three Hail Marys.) I beseech thee to have infinite pity in regard to the favor I ask of thee, Saint Martha, (name favor) and that I may be able to overcome all difficulties. Amen. This prayer has never been known to fail. You will receive your intention on or before the ninth Tuesday, no matter how impossible it might seem. Publication must be promised.

B.D.

—Fromthe Ambient WeeklyDecember1990

One

The boy, Gabriel, and his father stopped for the night somewhere north of Canton, Ohio. Around them, the land lay in one vast slab, the snow crust bright as water beneath the waxing moon. The nearest town was ten miles away, unincorporated, and there was nothing in between except a handful of farmhouses, Christmas lights burning in each front window; a few roads; fewer stop signs; a small white crossroads church. High above and out of harm’s way were the cold, gleaming eyes of stars, and each one was so strangely iridescent that if a man in one of the farmhouses had risen for an aspirin or a glass of warm milk, he could have been forgiven for waking his wife to tell her he’d seen—well, something. A glowing disk that swelled and shrank. A pattern of flashing lights. And she could have been forgiven, later, for telling people she’d seen something too as she’d stood by the bedroom window, sock-footed and shivering, her husband still pointing to that place in the sky.

But a wind came up in the early morning hours, scattering the stars and moon like winter seeds, so that by dawn the sky was empty, the color of a tin cup. It was the day before Christmas. The air had turned cold enough to make Gabriel’s nostrils pinch together as he stood in the motel parking lot, listening to his father quote figures about the length of time human skin could be exposed to various temperatures.

“It’s not like this is Alaska, kiddo,” Shawn Carpenter said, clattering bright-yellow plastic plates and cups from the motel’s kitchenette onto the floor of the station wagon. The old dog, Grumble, who was investigating the crushed snow around the dumpster, shuddered as if the sound had been gunshot. The previous day, she’d ridden on the floor between Gabriel’s legs, her face at eye level with Gabriel’s face, panting with motion sickness. There’d been nowhere else to put her. Behind the front seats, the space was packed with all the things that hadn’t been sold or lost or left behind: clothing, cookbooks, a color TV, a neon-orange beanbag chair, snowshoes, a half-built dulcimer, two miniature lemon trees in large lemon-shaped pots, and Shawn’s extensive butterfly collection, which was mounted on pieces of wood and enclosed behind glass plates. Whenever she’d started barking crazily, they’d been forced to stop and let her outside. The last time, it had taken over an hour of whistling to coax her back.

Shawn peeled off one of his gloves and held his bare hand out toward Gabriel. “One one thousand,” he said, counting out the seconds. “Two one thousand. Three one thousand.”

They were on their way to Ambient, Wisconsin. An oily light spread toward them from the edge of the horizon, and now Gabriel could see I-77 in the distance, a thin grey line slicing through the snowy fields, unremarkable as a healed-over scar. A single car crept along it, and he imagined it lifting into the air as lightly as a cotton ball. He imagined it again. If you believed in something hard enough, if your faith was pure, you could make anything happen—his fifth-grade teacher, Miss Welch, had told him that. Miss Welch was born again. Still the car kept moving at its careful speed, and Gabriel knew he must have doubted, and that was the only reason why the car kept dwindling down the highway to a point no brighter than a star.

“You see?” Shawn said, and he wriggled his fingers. “If this was Alaska, my hand would be frozen. If this was Alaska, we’d probably be dead.”

Grumble had found a grease-stained paper bag. Her tail moved rapidly to and fro as if she believed something good was inside it. Yet Grumble wagged her tail just as energetically at snowplows and mailboxes, at the sound of canned laughter on TV, at absolutely nothing at all.

“A dog, on the other hand, is a survivor. Warm fur, sharp teeth. A survivor!” Shawn said, and he must have enjoyed the sound of that word because he said it again as they pulled out of the parking lot. Gabriel stared back at Grumble, hoping she would look up, hoping she would not. Then he faced front and kicked the plates and cups aside, making room for his feet against the vent. He pulled off one of his mittens and picked up a cup, which he held in front of his glasses. Peering through the oval handle, he watched the land compress to fit into that tiny space. “She’ll find a nice family,” Shawn assured him. “She’ll forget all about us.”

Noreen had been much harder to leave behind. Shawn still owed her money from the camper, which they’d bought with money she’d saved from years of work at a small insurance company. That was when they still had plans to travel cross-country—Noreen and Shawn, Noreen’s son, Jeffy, and Gabriel—to Arizona, where the weather stayed warm and dry. Noreen had a soft Southern accent that made the things she said seem original and true, and she knew how to do things like make biscuits from scratch. It had been five months since Shawn and Gabriel moved into her one-bedroom apartment in Fairmont, West Virginia, and sometimes, during that first charmed month, when it was too muggy to sleep, they’d taken their blankets onto the tiny balcony and lain there beneath the stars, talking about the future—even Jeffy, who was only four and didn’t understand what anyone was saying. But the camper had brought one thousand dollars, money that would get them to Wisconsin and feed them until Shawn found work. He handed Gabriel the thick wad of fifties and hundreds, letting him feel its weight. “You’ll have to help out with expenses for a while,” he said. “A paper route, kiddo, how do you feel about that?”

Gabriel imagined slogging through the snowdrifts, dragging a wet bag of newspapers behind him. “Maybe I could work in a restaurant,” he said, although he wasn’t sure a ten-year-old could do that kind of thing, even if he was big-boned, the way people said.

“A paper route would be better for you—exercise, fresh air, all that.”

“OK,” Gabriel said warily—was his father going to start in on his weight?—but Shawn stuffed the money back into the deep pocket of his coat and turned on the radio. More soldiers were arriving in Saudi Arabia; aircraft carriers had moved into striking range of the Gulf. “Listen up, son,” Shawn said. “There’s going to be a war.” The sun was gaining strength, bloodying the hoarfrost that clung to the shrubs and the tall wild grasses that poked up through the snow crust at the edges of the highway. They passed an intersection boasting the world’s largest collection of rocks, a car dealership with its necklace of bright flags, a nursery selling Christmas trees beneath a yellow-and-white-striped tent. The land was flatter than any place Gabriel could imagine except, perhaps, heaven, with its shining streets of gold. Miss Welch had told the class all about heaven and Jesus Christ, and how, if they had faith the size of a mustard seed, they would be filled with the power of God and could perform any miracle they wished.

“You mean,” Gabriel said, “if I had a glass of white milk I could make it chocolate?”

“That’s right,” Miss Welch said. “But you’d have to believe with all your heart. Most people can’t do that. Most people have a little bit of doubt that they can’t overcome no matter how hard they try. Otherwise it would be easy to make a miracle happen. Anyone could do it.”

Gabriel picked up the rest of the cups and fitted them into a towering stack. He tried not to think about Grumble. He tried not to think about Noreen, who must be waking up to an empty apartment and a bare spot on the lawn by the parking lot where the camper had been sitting. He reminded himself there would be other girlfriends and dogs and Jeffys, although his father had assured him that this time things would be different because Ambient was the place where Shawn had grown up. This time, Shawn said, they were really going home.

In the past, when Shawn had talked about Ambient, it was to make fun of the people who lived there. Hicks and religious fanatics, he called them. Local yokels married to cousins. People with six fingers and bulging foreheads. Now he was talking about how much Gabriel was going to like countryliving. He talked about the way the sown fields around the town looked like a green and gold checkerboard, split by sleepy county highways where you could drive for an hour without seeing anything except meadowlarks, sparrow hawks, and red-winged blackbirds, and perhaps a sputtering tractor. He described the millpond, how on hot summer days you could dive off the wall of the old Killsnake Dam and float on your back beneath a sky so blue it seemed like a reflection of the water itself. He talked about the Onion River, which ran all the way from the millpond smack through the center of Ambient, where there was a park with a little gazebo and swings, and an old-fashioned town square with a five-and-dime, a pharmacy, and a café with an ice cream soda counter. An angel lived in the river, he said. In fact, he’d even seen it once: small and white, about the size of a seagull, hovering just above the water. But the absolute best part about Ambient was that both Gabriel’s grandfather and his uncle—Shawn’s older brother, Fred—lived in a farmhouse big enough so that Gabriel could have his own room. At night, he could lie in bed and listen to the freight trains passing through, just the way Shawn had done as a boy, imagining he was a hobo, a stowaway, rocked to sleep inside one of the cars.

Gabriel raised the stack of cups so the top cup touched the roof of the station wagon. He wondered if the angel was real, or if it was just something his father had made up so he would want to live there.

“Ambient,” Shawn announced, “is the perfect place for a boy like you to grow up, don’t you think?”

The station wagon swerved a little, and Gabriel let the cups collapse, a shattering waterfall of sound. Shawn jumped and accelerated into the breakdown lane. There was the raw hiss of tires spinning on ice, and for a moment, Gabriel saw the long fingers of the weeds reaching for him, close enough to touch. Then they were back on the highway.

“Goddamn it!” Shawn said. “See what you made me do?”

Gabriel picked up a cup that had fallen into his lap.

“You blame me for everything, don’t you?” Shawn said. “This is your way of getting back at me. This is your way of getting under the old man’s skin.”

He turned up the radio and they drove without speaking as the red sunrise dissipated into the steely morning. People were arguing over what the war was going to be about, if there even was a war at all. Gabriel tried to topple a thin stand of trees. He tried to make himself invisible. When nothing happened, he searched his soul for the blemish of doubt that, somehow, he must have overlooked. Noreen had been born again just like Miss Welch, and she said that Miss Welch was right: Pure faith made anything possible. She told Gabriel stories of people who’d had cancer and been completely cured without surgery or drugs, leaving the doctors mystified. She told Gabriel about modern-day people who’d seen Jesus sitting beside them on a bus or in a cafeteria or even walking along the road, plain as day. She told him about one time when she’d been broke and she’d prayed really hard for a lottery number. The number 462 appeared in her mind as if God had painted it there with His finger; she’d won five hundred dollars. Noreen was younger than Shawn and she wore red lipstick that stuck like a miracle to the complicated shape of her mouth. She loved bright colors and soft, sweet desserts. She was good to Jeffy, and she would have been good to Gabriel if he had let her, if he had not known in his heart that someday soon his father would decide he didn’t love her anymore.

Just before noon, Shawn pulled over at a rest area and parked the car at the edge of the lot, away from the kiosk. He moved the seat back as fer as it would go. “Tired?” he asked Gabriel tenderly. They were at the edge of a tiny strip of woods. The frosted ground was merry with soda cans and candy wrappers and bags of garbage people had dumped from their cars.

“A little,” Gabriel said.

“You’ll feel better after a catnap. Ten, fifteen minutes, and the world will be a brighter place.” He took off his woolly cap and tucked his gloves inside it, making a small round pillow. Then he wedged it between the seat and the door, put his head against it, and slept.

For a long time Gabriel waited, staring at the broad, blunt shape of Shawn’s chin, the fine hairs outlining his ears like an aura. He divided his father into parts and let his gaze move slowly, deliberately, over each of them. The lean, rough cheek. The neck with its strong Adam’s apple and the finger of hair curling out from the collar. The sloping shoulders beneath the dark coat, the long narrow thighs. He looked at his father’s crotch—there was no one to tell him not to—but then he made himself stop. An eyelash clung to the side of his father’s nose and, breathless, he reached over and flicked it away. When Gabriel was still a little boy, his father would occasionally allow him to comb his curly black hair, and afterward Gabriel would smell his fingers, the bitter mint of dandruff shampoo, the oily musk of his father’s skin. He’d make up his mind to concentrate harder, to stop daydreaming, to do better in school and make his father proud. He’d lie in bed imagining scenes in which he rescued his father from some terrible danger, and—over and over again—he’d imagine his father’s gratitude.

Shawn Carpenter was so handsome that people, women and sometimes men too, would stop on the street and turn their heads to look as he walked on. He had robin’s-egg eyes speckled with green, a dimple in his chin so deep you wanted to heal it with a kiss. He was an accomplished welder and electrician; he could fix cars and photocopiers; he was a natural salesperson, an elegant waiter, a creative and indulgent chef. And when he met another woman he wanted to fall in love with, it was hard for Gabriel not to be jealous. He watched him for the early symptoms of a crush like a parent alert for fever. There were sudden bouts of giddy playfulness, late suppers, a rash of practical jokes. Raw eggs in Gabriel’s lunch bag instead of cooked. A fart cushion under his pillow. Next came splurges: take-out pizza, television privileges, a toy that had been previously forbidden. There were professional haircuts for them both and, for Shawn, a trip to the dentist. Soon a woman’s name would ring from Shawn’s tongue too often, too brightly, an insistent dinner bell, and then would come the first awkward meal all together in a restaurant, with candles and fancy wine and a waiter quick to mop up any spills. One night, Shawn would stepoutforagood-nightkiss and not return until the next day, and tears would glaze his eyes in that moment before he shouted at Gabriel for forgiveness. “It’s hard,” he’d say, “raising you alone. Every day of my life since I turned eighteen I’ve spent looking after you.”

Eventually, they’d start moving a few things from wherever they were staying into the woman’s apartment or trailer or house or camp, and sometimes these places were elegant and clean, and sometimes they smelled of dog or fried potatoes, but ultimately none of that mattered because, eventually, they became the same. Shawn unpacked his butterfly collection and his beanbag chair, his dulcimer, his snowshoes, his cookbooks. He hung the butterflies on the living room wall, worked a little more on the dulcimer, and prepared chilled soups and golden puff pastries and fish baked inside parchment paper. He’d get to work on time each day and, at night, cut back on his drinking. He was charming and energetic; when he spoke, he waved his hands in the air. But it was always during these optimistic periods that he started to look at Gabriel with a shocked, critical eye, the way that Gabriel himself had looked at the world the first time he was fitted for his thick eyeglasses. “Kiddo, you were blind as the proverbial bat,” Shawn told him. “Things must look pretty good to you now,” but the truth of the matter was that everything had looked much better before, and sometimes Gabriel still took off his glasses to enjoy a stranger’s smooth complexion or a soft grey street, its velvet sidewalk lolling beside it like a tongue, the slow melt of land and sky at the horizon. “Where are your glasses?” Shawn would say. “I didn’t spend that kind of money for you to decorate your pockets.” Then everything jumped too close and filled with complicated detail: acne and scars and colorful litter, painfully double-jointed trees, clouds with their rough, unsympathetic faces.

Suddenly Shawn would decide that Gabriel needed more exercise, less TV. Perhaps it would occur to him that Gabriel should learn French, and then every night he’d have to listen to a tape that Shawn had ordered from a catalogue. Sometimes it was cooking lessons, Shawn standing over him as he tried to make a smooth hollandaise. It could be his posture, or his attitude, or his ineptitude at sports, and sometimes it was all three. He’d always remember one endless autumn, when they’d lived in Michigan with a woman named Bell, her three sons, and their basketball hoop. Every night, Gabriel had to practice jump shots and layups and free throws with the other boys. Every morning, he’d cross his fingers and stare up at the sky, willing winter to blow in early and leave the driveway slick with ice.

Eventually, Shawn would give up on Gabriel and turn to the girlfriend they were living with. At first, there were only a few small things, and he’d bring them to her attention reluctantly, sweetly, and always with a remedy: a permanent wave, adult ed classes, a more functional arrangement of the living room. He’d sit up late in the orange beanbag chair, drinking from his flask and writing scraps of poetry, and he’d sometimes oversleep in the morning. Around that time, the fights would begin, secretive at first: a hissed exchange in the bedroom; sharp voices from the porch. One night, Gabriel would awaken to find Shawn sitting on the edge of his bed. “What was I thinking?” Shawn would ask, his breath golden with Jack Daniel’s. “Next time,” he’d say, “warn me, kiddo. I’m pushing thirty. That’s too old to be making big decisions with the wrong damn head,” and he’d lie down on top of the covers beside Gabriel, and if Gabriel threw an arm over his chest, his father didn’t shrug it away.

It was always best between them just after they’d moved back into a place of their own or, more likely, pointed the station wagon toward a city or town where they hadn’t lived before, some place where Shawn still had a friend or two, somewhere he knew he could find work. Together they’d bask in the afterglow of leaving, and it was during these times that Shawn always brought up the possibility of moving back to Ambient. Maybe he’d find a job doing piecework for the shoe factory on the River Road, something that would leave him time to write a novel, a thriller; he was certain it would sell. Or maybe he could start a little business, run it with his brother—a landscaping company or, perhaps, a used-car dealership. “Kiddo,” Shawn would say, “I have got to get a grip on myself. I’ve got to get things together.” At times like these, with Shawn’s face flushed and open and hanging too close, Gabriel thought he might die of love for his father. “Daddy, it’s all right,” he’d say. “We’re fine, everything’s fine.” And when he thought about how fervently his father believed in those words, words that fell like manna from Gabriel’s own mouth, he truly understood the power of faith.

But now his father was sleeping. They were on their way to Ambient. There was no need for Gabriel to say anything. He dug down between the seats, looking for loose change, and when he’d collected enough dimes and nickels he got out of the car and went over to the kiosk. The vending machines were lined up in an outdoor alcove at the back, and he took his time before deciding on an Almond Joy. He ate the first section in one sweet, greedy bite; the remaining section he ate more slowly, licking off the chocolate to expose the clean white coconut beneath. Then he explored the small wooded area behind the kiosk. Finally, he sat down on a graffitied bench and flattened the empty Almond Joy wrapper, folded it into a fighter jet, guided it through barrel rolls and screaming dives and bombing runs. He wondered if his uncle and grandfather would really be glad to see him. He wondered if he really could have his own room, or if he’d be sleeping on a couch until Shawn found them a place of their own. His butt was getting numb from the coldness of the bench. His nose was running. His toes hurt. He decided that even if there was an angel in the Onion River, his father had never seen it.

A thin winter sunlight trickled through the trees, and he let his head fall back, thinking about the shapes the branches made against the sky. If an Iraqi plane flew over, he’d make it disappear, leave all those soldiers hanging like cartoon characters in midair. He imagined them falling to earth. He imagined their souls rising like milkweed, like dandelion seeds. Though he felt the thump of Shawn’s hand on his shoulder, it took him a moment to respond to it

“Like an idiot,” Shawn was saying, “with your mouth hanging open and chocolate all over your face. How old are you now? Eight? Nine?”

“I’m ten,” Gabriel said.

“Almost grown up,” Shawn said. “Almost a goddamn man. What do you think about when you sit there like a ninny? Girls?” He plucked the candy wrapper airplane out of Gabriel’s lap and threw it at the ground, but the wind caught it and sent it wafting away into the woods. “I hope to God it’s girls,” he said. “Christ” He pulled Gabriel up by the shoulder. “Where did you get the money for that candy?”

“The car.”

“A thief, on top of everything,” Shawn said. “Well, maybe your uncle and grandfather will have some idea what to do with you. Because I do not. Because I simply have had it up to here,” and he made a slicing motion across his throat

They walked back to the station wagon. As soon as they got inside, Gabriel’s teeth chattered stupidly. Shawn glared at him, then started the engine and turned the heat on high. “Scared me half to death,” he said, and he raked his hands through his hair. “What possessed you to get out of this car?”

“Hungry,” Gabriel said. His toes burned. He shifted them carefully, trying not to rattle the cups and plates and risk drawing further attention to himself.

“Hungry!” Shawn said, as if that were the most outrageous of possibilities. He pulled back onto the highway, and they drove for another hour, listening to talk radio. Now and then there were bursts of static, which made the people sound far away, as if they were calling from the moon. A man said the hell with the UN, the United States should drop the bomb. A woman said that if people over there wanted to kill each other, let them. They passed billboards advertising an adult bookstore, a barn with SEE ROCK CITY! painted on its roof, the carcass of a deer and, less than a mile beyond it, a hitchhiker, his face hidden by a multicolored scarf. They passed a low brick church decorated with a banner that read: PUT THE “CHRIST” BACK IN CHRISTMAS. They passed two white crosses at the mouth of an off-ramp, each decorated with a small green wreath. At the end of the ramp was a bullet-ridden stop sign where a van idled, as if the driver was uncertain, exhaust drifting lazily through the air. But all the county roads met at ninety-degree angles. There was never any question which way was left, which was right, which was straight ahead.

When Shawn finally spoke to Gabriel, his voice was softer. “You frozen anywhere?”

“Maybe my feet.”

“Kick your shoes off. Get them up against that vent. Does it hurt?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s good, kiddo,” Shawn said. “Pain is the way we know for certain that we’re living. If you only remember one thing your old man tells you, try and remember that.”

A truck passed them, traveling too fast, splattering their windshield with icy slush. Gabriel pictured it rolling over, bouncing off the guardrail, bursting into a perfect globe of fire. But though he believed without reservation, just the way Miss Welch had said, the truck slipped into the dark eye of the horizon. They were coming up on an exit. A McDonald’s sign floated high above the highway, dazzling against all that gray and white.

“Look at that!” Shawn said heartily. “The answer to your prayers! What do you want, a hamburger? Fish sandwich?”

Help bring the Christmas story to life! Human and animal volunteers needed for Ambient’s annual Living Crèche to be held in front of the railroad museum from noon till three on Christmas Eve Day. Costumes and hot chocolate provided. The manger will be heated this year! Participants and visitors alike are invited to warm up in the museum lobby where the Christmas Ornament Collection of Mr. Alphonse Pearlmutter will be on display.

—Fromthe Ambient WeeklyDecember1990

Two

You could ask anybody in Ambient: Fred Carpenter’s new wife, Bethany, wasn’t the type to bend her own rules. But that Christmas Eve, she allowed the men to bring their whiskey inside the house. Later, she’d say she’d had a feeling all along that something was about to happen, and it drove her to such distraction that when Fred asked her if just this once, for the holidays, they might have a round before supper, she nodded before she realized what he’d asked, what she’d done. The telephone rang, but when she picked up the receiver, a giggling child asked if her refrigerator was running. A lightbulb blew in the foyer and then, only minutes later, in the bathroom off the hall. For no reason whatsoever, a jar of sweet pickles slipped from her hand and shattered on the linoleum floor. More than once, she caught herself checking the sky above the field where, just last August, the legs of two tornadoes had stumbled, knock-kneed, toward the highway.

But on this day, the winter sky was plain and pale as her own face, and at six o’clock sharp, Bethany called everyone to the table: her boys and Fred and Fred’s father, Alfred, whom everybody called Pops. Pops was well known around Ambient; since losing his driver’s license for DWI, he’d been driving his tractor to Jeep’s Tavern each weekend, parking it on Main Street, forcing traffic to squeeze by. Now he wore the nice dress shirt Bethany had given him last Christmas, fresh from the box, all the creases intact. His beard—once dark and thick as Fred’s—had grown in pale and patchy since the night he’d accidentally set it on fire, heating up a pan of SpaghettiOs. Still, it brushed the clean surface of his plate as he hitched his chair up to the table. The water in the glasses shivered and danced.

“Already a few sheets to the wind,” Bethany complained, not bothering to lower her voice.

Pops said, “Hell, I only had two.”

Bethany said, “Language.”

The boys nudged each other and grinned.

“Well, heck, then,” Pops mumbled, cracking his knuckles as if he wanted to fight the Christmas ham. But the electric company had cut his lights again, and even Bethany could see he was pleased enough to be sitting under her bright chandelier. Outside the dining room window, not ten yards beyond the edge of the gravel courtyard, the farmhouse he’d occupied for sixty years loomed like a pirate’s ship—all it needed was a skull-and-crossbones to replace the tattered American flag that drooped from a boarded-up window, stripes faded pink. The yard was a carnival of discarded chairs and mattresses, tires, tractor parts, buckets of paint; the porch sagged beneath two mildewed couches where, in summer, Pops and the boys from Jeep’s gathered to talk dirty, to swap outrageous lies. Each year, the whole place leaned a little more to the right, and though Fred had spent the better part of one summer jacking up the central support, the house still looked like it wanted to slide off its foundation and slip away, embarrassed, into the fields.

“Now, Beth,” Fred said from time to time, twisting at his beard until it formed an anxious point “It seems to me we might have Pops over for a hot meal now and again.” But Bethany refused to pity Pops. She figured he made his bed each time he headed for the liquor store. After all, he had his social security, plus whatever he earned doing odd jobs for Big Roly Schmitt—that is, when he made up his mind to work. She had him to supper on holidays, of course; beyond that, she drew the line. Otherwise, she knew, he’d be crossing the courtyard every night of the week to eat her good food and stink up her nice furniture, to mistreat her house the way he’d done his own and infect her boys with his laziness.

Back when Fred had first proposed, Bethany saw he had some idea about her moving into those cat-piss-smelling rooms, looking after his father, imposing some order on their lives. Even then Fred’s beard was thick enough to hide his mouth, but Bethany saw the smug pride in his eyes, how he expected her to leap for that ring like a cat for a bird. After all, at the time she was a thirty-something waitress, mother to two boys who’d never had a father’s name. But Bethany told Fred, “Listen once. We’re not kids so we can be straight with each other. If you marry me, you are getting two fine sons and a wife who will cook you the best meals you’ve ever eaten, and keep a nice garden, and make sure your clothes are tidy-looking, and don’t forget I’ll be out there earning money too. When the lights go out I’ll never say no, provided you keep yourself clean. So that’s a good deal for you and well worth the cost of a house I’ll be proud to live in.”

She’d surprised him, but Fred was quick on his feet. He said, “There are gals who’d take it as a challenge to fix an old farmhouse into a showplace.”

“I guess you should propose to one of them,” she said.

He set his beer down on the coffee table; she nudged it onto a coaster. It didn’t take much to leave a ring.

“I guess you should take another look in those magazines you’re always reading,” he said. “Half those ladies’ fancy places are old farmhouses somebody smart bought cheap. I’d give you a thousand dollars,” he said, and he paused to let that sink in. “You could spend it however you pleased.”

She took a BetterHomesandGardens from the magazine rack and held it out to him. “Show me,” she said, “where one of these fancy places comes furnished with a half-crazy drunken old man.”

She knew he had money for a decent house—a thirty-six-year-old bartender who sleeps in his childhood bed can save a pretty penny—but he said, “I have to do some more thinking on this,” and walked out, taking that ring along with him. Her mother said, “Oh, Bethany, look what you did, those boys will never have a father now.” And Bethany said, “Ma, these boys live in a two-bedroom apartment with carpet on the floors and cereal in the cupboards, which is more than any father ever gave them.” True, she was lonely, but if it came down to a choice between a man who’d have them live dirt cheap and dirty, or her own waxed floors and freshly scrubbed windows, Bethany was proud to choose door number two. Why marry if it didn’t improve your standing, make things a little easier on yourself? Why lose control of the few things you’d finally managed to get a firm grip on?

She would never forget how she and her sister had had to walk on tippy-toe around Pa, how Ma was always saying, Nowdon’tupsetyourfather,nowleaveyourfatherbe, like he was some wild animal they’d lured in with table scraps. They’d lived in a duplex, rented their side from a man named Mr. Shuckel. When he came to the door to ask about rent, Pa always sent little Rose to say nobody was home, but Mr. Shuckel hollered at her just like she was a grown-up. Now Pa was long gone and Ma had moved in with Rose and her three half-grown kids. She lectured Rose and Bethany both about how her children always had a father, how they’d been a real family, not like you younggalstoday. Bethany ignored her the same way she ignored the politicians on TV.

She’d never voted, hadn’t even bothered to hear George Bush when he stopped to give a stump speech in Cradle Park. What did this politician, or for that matter any other, care what she had to say? She could have told them that a happy family didn’t start with the right church or a fancy school or x many cops on the street. It started with a nice place to live. And when Fred returned three months later, that same ring hooked to a house key, Bethany married him right there in her heart—Father Oberling’s ceremony at Saint Fridolin’s Church had little to do with it. It was a home that cleaved two into one, and it was only their second Christmas together when Shawn Carpenter showed up to spoil it all.

They had just said grace, something they did only on holidays—Bethany saved prayer for special occasions, the same way she saved her good china. “Everything looks great,” Fred said, and he stood up to carve the ham, which was wrapped in a pineapple-and-cherry necklace Bethany had copied from the cover of GoodHousekeeping. There were side dishes of scalloped potatoes and carrot salad piled high in a Jell-O ring and squash with marshmallow topping. There were baby canned pear halves spread with cream cheese, garnished with a dab of mint jelly. A perfectChristmasdinner, Bethany thought A perfectfamilytoenjoyit. She silently challenged Ma or the tight-lipped ladies she cleaned house for or even George Bush himself to say it wasn’t so. Then her heart froze at the sound of somebody pulling into the driveway. “Who’s got a big brown station wagon?” she said. It stalled on the ice, slipped back, lurched ahead so that it spun a cookie in the courtyard, crashing into the drift along the snow fence.

“What the hell,” Pops said, standing up to look.

“Language,” Bethany said.

“What the hooey,” he corrected himself.

“It’s two of them,” Bethany said. “They’re headed over to the farmhouse.”

“Maybe it’s Santa and Rudolph,” Pete said sarcastically.

“Ho ho ho,” Pops said.

“Maybe it’s Saddam Hussein,” Robert John said.

“Hush,” Bethany said. “That’s not table talk.” Fred finished off the last of his whiskey; Pops wobbled slightly as he followed him to the door. “Hullo?” Fred called, and Pops hollered, “We’re over here!” Then the cold air sucked all the good food smells out into the night and, in exchange, presented them with Shawn Carpenter.

Bethany knew from the get-go who he was—she’d heard all about his good looks and bad habits from Lorna Pranke, the police chief’s wife, one of the nicer ladies she cleaned house for. Fred himself didn’t talk about Shawn much, just said he had ways of making bad ideas sound sensible. But Lorna had told of how he’d stolen and scammed and disturbed the peace and generally made a nuisance of himself, how for years you couldn’t open the AmbientWeekly without finding his name under “Citations.” The chief lost many a good night’s sleep before Shawn graduated from high school and left town for good. Whenever Bethany asked Fred about the things Lorna told her, he’d neither confirmed nor denied them. “Now, now,” he’d said. “You want to dig for skeletons, you keep to your own closet.”

“Surprise!” Shawn yelped, and he grabbed Fred and thumped him on the back right where it was always sore from standing at the bar. That spot, if you pressed your hand to it, would bring tears to his eyes, and Bethany felt that pain all the way up her own spine. But Fred only moaned and grabbed his brother harder, and the two of them hugged like no two men she’d ever seen, the way women hug, or lovers.