Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

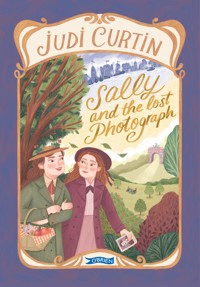

- Serie: Sally in the City of Dreams

- Sprache: Englisch

Sally and her sister Bridget are New Yorkers now – they've settled in and feel at home in the bustling city. Life in New York is exciting enough that the girls can rise above life with Catherine, their mean cousin. At work one day, Bridget finds a photograph of a young man between the pages of a book. She shows it to her employer Miss Cameron who dismisses it, but her blush and flustered manner intrigue Bridget; she soon discovers he was a suitor, but not allowed by Miss Cameron's family as he came from a poor background. Meanwhile, the girls' friend Betty is sick. When she visited a free clinic the doctor suggested she move to a warmer part of the country, a prospect unimaginable to Betty, who can barely afford to feed and clothe herself. When poor Betty commits a crime out of poverty and desperation the girls don't know how to help. But can both stories have a happy ending?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 220

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Sally in the City of Dreams

‘For sheer, unadulterated reading pleasure, there’s little that matches Sally in the City of Dreams.’

Books for Keeps

‘Nobody writes warm, kind friendship stories quite like Judi Curtin, and this new historical novel, set in New York in the early 1900s, is her best yet.’

Irish Independent

‘Judi Curtin at her best. Sally and Bridget’s story is both tenacious and gentle as they navigate what it means to be an Irish immigrant in America.’

Irish Examiner

2

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the Sunday Walkers4

Contents

5Brooklyn, New York, Early 1900s

Chapter One

‘See you later, Catherine,’ I called as Bridget and I put on our coats. ‘I hope you have a lovely afternoon.’

My sister made a face at me. She hated that even after all this time I still sort of hoped that our distant cousin Catherine would one day turn out to be a nice person.

Catherine came out of her bedroom and glared at us. ‘I mustn’t be charging you enough rent if you’ve money for all this gallivanting around New York. The trouble is, you girls don’t appreciate how lucky you are to have a room of your own.’6

‘Lucky? You’re the lucky one. We pay you a dollar every month for that tiny thing you call a room.’ As Bridget spoke, she pointed to our corner of the parlour. A curtain separated it from the rest of the room, and inside was a mattress, which until a few days earlier we’d shared with our friend Julia. Julia’s brother, Sonny, used to live in The Bronx with his wife Elena and their little baby, David. Now, though, they had a bigger place here in Brooklyn, and Julia had gone to live with them there.

‘Oh, that reminds me,’ said Catherine with a mean smile. ‘Now that Julia’s gone, I’ll be looking for someone else to take her place. Maybe by the time you come back you’ll have someone new to share with.’

Now even Bridget was speechless. The mattress had been a terrible squash when three of us were sharing, but we didn’t mind, as Julia was such a dear friend. Sharing with a stranger would be very different – and not in a good way.

Bridget found her voice. ‘Even you, Catherine,’ she began. ‘Even you wouldn’t...’

7I took Bridget’s arm and led her towards the door. I love my big sister with all my heart, but I live in fear of her quick tongue getting us into a lot of trouble. Catherine was a mean, grasping woman, but we’d nowhere else to live except with her. Even if Bridget and I managed to find a vacant room, we could never afford it – our jobs didn’t pay that much, and we tried to save a little to send home to Ireland too.

What if Catherine asked us to leave?

What if she found new girls to take our place?

Where would Bridget and I go?

How would we live without a home?

This time Bridget chose not to continue the fight. As she followed me out the door and down the long stairs, I allowed myself to breathe again.

* * *

I turned my face to the sun, enjoying its gentle heat on my skin, so welcome after a long, cold winter.

8The buildings around us were tall, but nothing compared to the huge skyscrapers over in Manhattan. The street was busy and buzzing with bicycles and horses and motor cars, but we were used to the noise and excitement by now. These days it was hard to imagine the quiet of our old home in Cork.

Bridget and I strolled along with our arms around each other’s waists, the way New York girls did. We were no longer newcomers, no longer unsure of where to go or what to say. Now we felt like real Americans.

I held my head high as we walked along. Nowadays the shawls we’d brought from Ireland were only used to keep us warm in bed on cold nights. We’d both saved up and bought very nice wool coats from the second-hand clothes shop. Our boots were old, but had no holes in them, and we both wore lovely gloves our granny knitted for us on our last Christmas in Ireland.

We dodged around a few thin, dirty children who were searching the gutters for rags and scraps of silver 9paper to sell at the junkyard. They’d only make a few pennies for their day’s work, and compared to them, Bridget and I were rich indeed.

‘I can’t wait to see Julia,’ said Bridget. ‘I miss her since she stopped living with us.’

I missed our friend too, but for her sake, I couldn’t be happier. We’d met Julia on our voyage from Queenstown in Cork. She’d come to America all on her own, but we’d helped her find her brother Sonny and his family. Now she was living the life she once only dreamed of.

‘She’ll be all talk about little David,’ I said. ‘She loves that baby to pieces.’

‘I guess you’re right.’

I smiled. These days all Bridget’s sentences started with ‘I guess’. One more sign of how American we were becoming.

* * *

10It wasn’t far to the tea shop, where we were lucky to get a table near the window. I was a little shy of the brisk girl in the bright white apron who came to take our order. Luckily, Bridget wasn’t shy of anyone at all.

‘Our friend will be here in a minute,’ she said. ‘So we’d like three cups of tea, and one sugar bun cut up into three pieces – equal pieces, please, so we don’t kill each other fighting over the biggest one.’

The waitress laughed as she wrote the order in her little notebook, stuck her pencil behind her ear, and went back behind the counter.

We’d just poured out our tea when we saw Julia coming through the door.

‘Julia,’ I said, jumping up. ‘It’s so nice to…’

I stopped when I saw a rough-looking girl walking right up behind my friend, so close she could easily reach Julia’s purse. The girl wasn’t wearing a coat or shawl or anything. Her dress was clean, but almost threadbare, and torn in a few places. Her boots looked sturdy enough, but instead of having laces, they were 11tied up with twine. The girl made me nervous. New York was full of pick-pockets, and we had to be careful to mind the precious money we worked so hard for.

I didn’t want to make a fuss, and draw attention to us, but I had to say something. Julia was coming our way, and the girl was still right behind her, suspiciously close.

‘Julia,’ I said, pointing. ‘Watch out for…’

Now they were beside us and Julia was turning towards the girl.

‘Bridget, Sally,’ she said. ‘I’d like you to meet my friend Betty – I’ve asked her to join us. Betty, these are my dear friends I told you about. The ones who were so very kind to me when I first got to New York.’

I could feel my cheeks turning pink, and they went even pinker when Julia looked puzzled and said, ‘What’s wrong, Sally? Were you warning me about something?’

‘No,’ I muttered. ‘I was only…’ I couldn’t finish the 12sentence. I felt so ashamed and mean. I know what it’s like to be judged for how I look and sound. Why did I presume that because this girl looked poor, it meant she was dishonest too?

Dear Bridget knew me so well and guessed what I’d been thinking. She took my hand and squeezed it, showing me she understood.

‘Someone spilled milk on the floor a few minutes ago,’ she said. ‘I guess Sally didn’t want you girls to slip and fall. Wouldn’t it be terrible altogether if one of you broke an arm or a leg? Wouldn’t it ruin the whole afternoon on us?’

Everyone laughed, and no one noticed that the floor was perfectly clean and dry, and I knew everything was going to be all right.

* * *

As soon as the girls had found chairs, Bridget waved at the waitress. ‘I’ll order some more tea for you, Betty,’ she said.

13‘And maybe we can get another sugar bun to share,’ I added. I love sugar buns and wasn’t sure a quarter of one would be enough for me.

‘No,’ said Betty quickly, as the waitress came over. ‘I’m not hungry. I don’t want anything at all – or maybe just a drink of water, if it’s not too much trouble.’

‘No trouble at all,’ said the waitress, hurrying away.

‘Everyone’s hungry when there’s sugar buns,’ I said. ‘How could you…?’

I stopped talking as I saw Betty’s embarrassed face. The poor girl! Despite what she’d said, she looked very, very hungry. Maybe she’d no money at all for things like tea and buns; small, occasional treats that Bridget and I allowed ourselves every week or two.

Now the waitress came back, carrying an empty cup and a plate with a sugar bun on it.

‘That pot of tea I brought earlier is surely enough for ten of you,’ she said, placing the cup in front of Betty. ‘And a silly man ordered this bun and then 14changed his mind about eating it and it’d be a sin to put it in the trash.’

I looked at the waitress’s smiling face and remembered Mammy saying there are kind people in every single corner of the world. I thanked her with a smile, and Bridget took charge of dividing the new bun so we’d all have the same amount.

Chapter Two

‘Betty works in the dress factory with me,’ said Julia. ‘I think I’ve told you about her before.’

Bridget looked as puzzled as I felt. Julia often talked about the people she worked with, but I couldn’t remember any mention of a girl called Betty. It seemed a bit mean to say that though, making Julia sound like a liar.

‘She’s the one whose cousin is a lawyer,’ continued Julia.

Now I knew exactly who she was. Julia had said the other factory girls called her Inky, because her fingers were often ink-stained from giving fingerprints after being arrested for shoplifting. I tried to seem casual as I glanced at Betty’s fingers and was a little disappointed when I saw they were as pink and clean as my own.

16Despite all the arrests, Betty had never been convicted – her lawyer cousin always defended her. No one was ever sure if she was guilty, though. I could understand that – Bridget and I knew all too well that being Irish meant you were often accused of crimes you hadn’t committed.

Julia had told us that Betty was a lovely girl, so I decided not to think about the fingerprints and the accusations and the court cases. Also, now that she was sitting across from us eating a sugar bun, I knew that whatever colour her fingertips were, calling someone Inky really wasn’t very fair or nice.

I smiled as I poured her some more of the lovely hot tea. ‘I’m glad you came, Betty,’ I said. ‘Any friend of Julia’s is a friend of ours.’

Betty started to reply, but got a fit of coughing that made her thin body shake. As she struggled to catch her breath, Julia gently rubbed her back. People around were beginning to mutter and stare at us. I don’t like being the centre of attention and couldn’t 17help feeling embarrassed, but Bridget put on her crossest face and stared right back at them.

‘I’ll go … outside,’ wheezed Betty in a break between coughs.

‘I’ll go with you,’ said Julia, jumping up.

‘No,’ said Betty. ‘I’ll be … grand in a minute when I get a … breath of air. Sit down and enjoy your tea … I’ll be back … soon.’

‘The poor girl,’ I said when she was gone. ‘How long has she had that cough?’

‘She’s had it ever since I’ve known her,’ said Julia. ‘But it’s getting worse. The winter was very hard on her – and the dress factory work doesn’t help. The threads and fluff from the fabric seem to irritate her throat.’

‘That’s awful,’ said Bridget. ‘Maybe she should get a different job.’

‘Yes, she definitely should,’ said Julia. ‘But the cough means she’s often too sick for work, so she misses a lot of time. That, and her court appearances mean no 18one else would employ her. I’m not sure why our boss keeps her on at all.’

‘Perhaps he’s a kind man,’ I said.

Julia laughed. ‘I guess he’s kinder than some, and he hasn’t put Betty out yet, but he’s not a complete saint. If she doesn’t work she doesn’t get paid, so she’s always short of money.’

‘Has she any family who can help?’ asked Bridget.

‘Only that distant cousin, the lawyer,’ said Julia. ‘He’s gone from New York now, and I think he was fed up of helping Betty anyway. He was ashamed of his connection with her.’

‘Has she no one else at all?’ asked Bridget.

‘No one in the whole world. She was an only child and her parents died when she was a baby,’ said Julia, making me want to cry at the sadness of it.

‘Has she been to see a doctor?’ I asked. Sometimes there were free clinics for people like us who couldn’t afford to pay for medical help.

‘She went to a clinic a few weeks ago,’ said Julia. 19‘But it didn’t help much. The doctor gave her a bottle of medicine that didn’t make any difference at all, and lots of useless advice.’

‘What kind of advice?’ asked Bridget.

‘And why was it useless?’ I added.

‘I guess the advice would’ve been fine for someone else,’ said Julia. ‘But it was useless for Betty. The doctor said she should stop working at the factory, and move to a warmer climate, like California or somewhere. The poor girl can barely feed or clothe herself, so those things are like impossible dreams. California! He might as well have suggested she get a spaceship and travel to the moon – as if that could ever happen.’

‘What can we do to help?’ asked Bridget.

‘We don’t really need our shawls anymore,’ I said. ‘Would Betty take one of them? Or both? She looks frozen half to death – and that can’t be helping her cough.’

‘No,’ said Julia. ‘She’s fiercely proud and won’t take 20charity from anyone. Even accepting this tea and bun is a big deal for her. She’s…’

She stopped talking suddenly and I turned to see Betty behind us. She wasn’t coughing, but her eyes were red, and she looked exhausted.

‘Are you all right?’ I asked.

Betty smiled, and her whole face lit up as if the bright California sun was shining on it. ‘Sure I’m grand altogether. This old cough will be better before I’m twice married.’

The four of us laughed and settled down for a chat.

Chapter Three

‘Tell us about life with Sonny and his family, Julia,’ said Bridget. ‘Do you miss us? Do you miss Catherine?’

‘I definitely don’t miss Catherine,’ she said. ‘But I do miss you two. I miss the chats we used to have before falling asleep at night. But … well … life is good.’

‘You don’t have to feel bad about being happy,’ I said. ‘We’re glad for you, aren’t we, Bridget?’

‘Of course,’ said Bridget.

‘Everyone’s delighted for you, Julia,’ said Betty with a huge smile. ‘You’ve had some hard times and now you deserve all the happiness in the world.’

I couldn’t help staring at this poor, sick, ragged girl. Life had been so cruel to her, and yet she didn’t grudge Julia one speck of her good fortune.

22‘Tell us all the details,’ said Betty. ‘We want to know every single thing, don’t we, girls?’ I loved the way she acted as if she, Bridget and I had been friends for years.

‘Well,’ said Julia, taking a deep breath. ‘Since you insist – life with Sonny and his family is simply perfect. The apartment is very small, but there’s just enough room for the four of us. The bathroom is on our floor, and there’s only five other families sharing it, so that’s good. Sometimes there’s hardly any queue at all. We have a parlour, a bit like the one at Catherine’s place, except even smaller, so that’s where we cook and where Sonny and Elena sleep.’

‘And what about you and the baby?’ I asked.

‘That’s the best bit – Baby David and I have a room all to ourselves.’

‘A room just for the two of you?’ Such luxury was hard for me to imagine.

‘It’s a very tiny room,’ said Julia. ‘If I stand in the middle of our mattress, I can stretch out my arms and touch each of the walls.’

23This confused me. We all knew (though it was hard to believe) that in New York, most of the tenement buildings where poor people like us lived had once been home to a single very rich family.

‘Why would rich people build such a tiny room?’ I asked.

‘I think it might once have been a linen cupboard,’ said Julia laughing. ‘I can see the marks on the wall where shelves must have been before – but that doesn’t bother me at all. To me it’s my own little bit of paradise.’

‘Tell us more,’ sighed Betty, almost as if Julia were telling us a fairy-tale, one we knew was going to have a happy ending.

‘David is the sweetest boy in the whole world.’

As far as I was concerned, my little brother Tom, who I missed so much, was the sweetest boy in the world – closely followed by my other brother Joe, and Dominic, the darling I took care of in New York. (I hope every small boy in the world is 24the sweetest in someone’s eyes.) But I knew Julia wouldn’t want to hear any of this, so I said nothing as she continued.

‘David sleeps on his tummy with his bottom in the air,’ said Julia. ‘And I curl up next to him. If I wake in the night, I put my hand on his warm back, and listen to his snuffly breathing, and I can hardly believe what a lucky girl I am.’

‘But doesn’t David wake you up at night with his crying?’ I asked. ‘Our sweet Tom was a terror, and poor Mammy hardly got a wink of sleep for the first year of his life.’

‘Ah, he hardly wakes at all, the little pet,’ said Julia. ‘And when he does, he cuddles up next to me and twiddles a lock of my hair until he falls back to sleep. Sometimes he accidentally pulls a bit hard, and if I squeal, he stops twiddling and pats my cheek with his fat hand, trying to say sorry.’

‘Sweet,’ sighed Betty, who’d never had a baby brother or sister at all.

25‘What about Elena?’ asked Bridget. ‘Is she kind to you?’

Julia had only met Sonny’s wife a few times before they all moved in together, so hadn’t known her very well.

‘Elena’s a perfect dote,’ said Julia. ‘She’s always hugging me and telling me how happy she is that we’re sisters. She goes out to work in the mornings, while a neighbour takes care of David. She’s back early, though, so when Sonny and I get home, Elena always has a lovely hot dinner ready for us. We all sit down at the little table, passing David around like a soft cuddly parcel, and we eat the dinner and chat and laugh and … oh, after Mam and Dad died, I thought I’d never be happy again, but I am. I really and truly am.’

I wished Bridget and I didn’t have to live with our mean old cousin, but then I glanced at Betty, who had much more reason to be jealous. Betty was gazing at Julia with a look of joy on her face, almost as if Julia’s 26happiness was enough to make her forget all her own troubles.

‘Where do you live, Betty?’ asked Bridget. My sister was being kind, trying to include Betty in the conversation, thinking it must be hard for her, listening to Julia talking about her perfect life – but Bridget had made a mistake.

The smile faded from Betty’s face, and I watched in horror as a single tear ran down her pale, thin cheek.

‘I … I live not too far from here,’ she said. ‘I share a room with two German families.’

‘How did you learn to speak German?’ asked Bridget.

‘I can barely speak a word,’ said Betty. ‘And they don’t have much English, but that’s not too big a problem. We smile at each other and point at things. I’m lucky to have a corner of the room to myself, so mostly when I’m not at work I lie on my mattress and read a book, or sleep.’

That sounded like a very lonely life to me.

‘Are they kind to you?’ I asked.

27‘Yes, I think they are good people. They don’t have a lot, but sometimes if they see I have nothing to eat – you know if I forgot to go to the shop – they share some of their German bread with me. It’s dark and tastes a bit funny, but …’

Julia leaned over and held her friend’s hand, and suddenly Betty dropped her head on to the table and started to sob.

‘What is it, Betty?’ I asked. ‘Are you hungry? We could buy another sugar bun. Or maybe a bowl of soup?’

Bridget and I saved most of our spare money to send home to Mammy and Daddy, but I knew our parents would want us to help our new friend.

Betty lifted her head. ‘Thank you, but I’m not hungry. I had breakfast this morning, and I’ve some potatoes saved for my dinner. It’s just that, it’s …’

‘What?’ said Julia. ‘What is it, Betty? Tell us how we can help you.’

‘No one can help me,’ she said. ‘One of the German 28women tried to explain something to me the other day, but I couldn’t understand what she was saying. She kept pointing to the door, and the stairs, and I thought she wanted me to fetch something for her, except I didn’t know what. And then last night, the man who speaks the best English was there, and he said I have to leave the apartment.’

‘But why?’ asked Bridget. ‘Why would they ask you to leave? Have you paid your rent money?’

‘Yes. That’s the first thing I do when I get paid. I can always manage somehow for food, but I need a roof over my head.’

‘So if you pay your rent,’ said Julia. ‘Why are they asking you to leave?’

‘Some of their cousins are coming from Berlin soon, and they need my space. I’ll have to move out in a few weeks. They said they’re sorry, but they have to put family first. I understand, but I don’t know where I’m going to go.’

‘I’ve got a great idea,’ said Bridget. ‘You could …’

29I shook my head at her, and for once she paid attention to me, and stopped talking. Of course, I’d been thinking the same thing. The space Bridget and I shared was tiny, and not really big enough for three, but if Catherine insisted it be filled, why not ask Betty to move in with us?

But I felt we shouldn’t suggest it to Betty; I could see she was a sweet, kind girl, but would Catherine recognise that too?

Would our cousin let someone who looked like Betty stay in her apartment?

Would she judge by appearances, the way I had at first?

And if we raised Betty’s hopes, how would she cope if Catherine rejected her?

‘Sorry,’ said Bridget, understanding the problem. ‘I’ve just realised my great idea wasn’t so great at all. Forget I said anything. Now, who wants this last scrap of bun?’

Chapter Four

Dear Mammy and Daddy and Aggie and Joe and Tom and Granny,

I hope ye are well. Bridget and I are the finest. I told ye that Julia would be leaving and now she has, but Catherine says someone else will have to share our tiny little space in the parlour. (Mammy, I know Catherine is your cousin, and I’m sorry to say this, but she isn’t a nice woman. You’re the kindest person I know, and you taught Bridget and me to be the same, but I don’t think anyone ever taught Catherine that lesson. That woman doesn’t have a kind bone in her body.)

Anyway, Julia has a friend called 31