Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

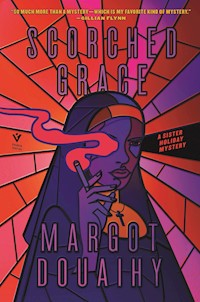

When Saint Sebastian's School becomes the target of a shocking arson spree, the Sisters of the Sublime Blood and their surrounding community are thrust into chaos. Unsatisfied with the officials' response, sardonic and headstrong Sister Holiday becomes determined to unveil the mysterious attacker herself and return her home and sanctuary to its former peace. Her investigation leads down a twisty path of suspicion and secrets in the sticky, oppressive New Orleans heat, turning her against colleagues, students, and even fellow Sisters along the way.Sister Holiday is more faithful than most, but she's no saint. To piece together the clues of this high-stakes mystery, she must first reckon with the sins of her chequered past - and neither task will be easy.An exciting start to Margot Douaihy's bold series that breathes new life into the hard-boiled genre, Scorched Grace is a fast-paced and punchy whodunnit that will keep readers guessing until the very end.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

“Within five pages, I was in love with this novel”

GILLIAN FLYNN

“Skillfully plotted, propulsive, and deeply engaged with the communities it represents, Scorched Grace is one of the best crime fiction debuts I’ve come across in a long while”

DON WINSLOW

“Vibrant, crackling and deliciously insubordinate”

MEGAN ABBOTT

“Douaihy’s prose is fresh and energetic, and she brings the delightfully original character of Sister Holiday vividly to life. Holiday believably leads her own investigation, and the story satisfies right up until the very twisty end”

KARIN SLAUGHTER

“Takes readers on a searing journey through faith, fire, and female rage. A brilliant debut mystery”

ELIZABETH HAND

“Scorched Grace burns with the wholehearted energy of faith, love, and transgression. Sister Holiday embodies the frailties of faith, the contradictions of humanity, and the joy of sisterhood in all its forms”

SOPHIE WARD

“Stunning fiction debut… [a] briskly plotted master class in character development… Douaihy is off to a terrific start”

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, STARRED REVIEW

SCORCHED GRACE

A SISTER HOLIDAY MYSTERY

MARGOT DOUAIHY

CONTENTS

SCORCHED GRACE

1

THE DEVIL ISN’T IN the details. Evil thrives in blind spots. In absence, negative space, like the haze of a sleight-of-hand trick. The details are God’s work. My job is keeping those details in order.

It took me four and a half hours to do the laundry and clean the stained glass, and my whole body felt wrecked. Every tendon strained. Even swallowing hurt. So, when my Sisters glided into the staff lounge for the meeting, folders and papers pressed against their black tunics, I slipped into the alley for some divine reflection—a smoke break. It was Sunday, dusk.

Vice on the Sabbath, I know. Not my finest moment. But carpe diem.

An hour to myself was all I needed. An aura of menace taunted me all day. The air was thick and gritty, like it wanted to bare-knuckle fight. Sticky heat, typical in New Orleans, but worse that day. The sun, the swollen red of a mosquito bite. Slow simmer belying the violence of the boil. I couldn’t sit through another reprimand.

Fall term was a week in, and two kids had already filed grievances about me. She’s always on us—a student scrawled—I can’tfeel my fingertips! Another (anonymous, I might add): Musicclass is TORTURE!!! I worried that Sister Augustine—our principal and Mother Superior, sturdy and sure as a sailor’s knot—would interrogate me in front of everyone during Sunday’s meeting. Which would inevitably lead to Sister Honor’s weaponizing of minor infractions for her crusade against me. That woman’s bullshit was so skillfully honed it was almost holy. And sure, my expectations were high. The highest. Saint Sebastian’s School was one of the few private Catholic schools left, far from fancy but definitely elite. I made my classes practice for an hour at a time, five days a week. Like they were real ensembles. How else would they learn? Day in, day out, you must commit. I’d be doing the students—and God—a disservice otherwise. To suffer is a privilege.

Pain is evidence of growth.

The ache means we’re changing.

And everyone is capable of change. Even me.

But that doesn’t mean I always got it right. Whenever I was punished, my task was to clean the massive stained glass windows of the church. I’d climb up on our rickety ladder and shine the glass, pane by intricate pane. Eleven in total. Bold blue, coral, fern green, and my favorite, sanguine, the color of sacred wine, the living red of a singing tongue during vespers. Our stained glass told stories from the Old and New Testaments. Moses, akimbo, parting the cerulean sea. The Evangelists: Matthew as a winged man; Mark as a lion; Luke as a flying ox; and John, an eagle. The slow-motion trauma of the stations of the cross. Adoring angels floating above the manger during the birth of Christ, our Lord, holding luminous harps like jewels in their small hands. So beautiful, it hurt to look sometimes.

Like watching people in church as they kneel and pray. Howl and lose balance. I see people at their absolute lowest. I hear people beg God and Mary and Jesus for second chances. One planet away from their spouses or kids next to them in the pew. Or so alone, they’ve thinned to ghosts. We’re always there, us nuns, to witness, to hold space for miracles in the terror, in the boredom, in the gore of life. To take it in, watch your hands tremble, validate your questions, honor your pain.

You never see us seeing you. Nuns are slippery like that.

With my special cloth, I wiped Jesus’s crown of thorns and the doves of peace. The gilded vignettes reminded me of my tattoos, ink I was required to cover, even in the soupy heat of August, with black gloves and a black neckerchief—one of Sister Augustine’s contingencies.

Cleaning the windows was supposed to be my penance, and it was bone tiring, but I liked the work. Each panel bewitched me. Better drama than Facebook. Or a bar fight.

Sometimes, Jack Corolla, one of Saint Sebastian’s janitors, brought his ladder to help. Help was a generous verb. I’d often have to climb down and anchor his ladder, as he was remarkably clumsy and scared of heights. Jack loved the seraphim window the most, besotted with the angel’s fine hair, the incandescent gold of lightbulb filament. “It’s it’s it’s the curse of an ancient building like this,” is how Jack explained, in his Southern lilt and stutter, every single problem he couldn’t fix on campus. Leaky pipes, flickering lights, whatever. Jack was paranoid about lead in the water and mold spores after storms, convinced something bad was always about to happen. He reminded me of my kid brother, Moose. Neither would ever admit to being superstitious but sure as the sun sets in the west, they both knocked on wood in threes. “Double filter your water, Sister!” Jack warned. “Once ain’t enough. Double filter!” Concern bordering on harassment. Sweet harassment. Both guys liked to shoot the shit and tag along under the pretense of work. Both fancied themselves handymen while being the least handy men in the room. But we reinvent ourselves, don’t we? We keep trying because transformation is survival, like Jesus proved, like Moose taught me. My brother knew better than anyone the cost of living your truth. I wish I had listened to him earlier.

During the first of countless castigations doled out by Sister Augustine, I discovered that if you pressed your face to Mary’s face in the Nativity glass, you could peer right through her translucent eye and see New Orleans shimmering below like a moth wing. On the highest rung of the ladder, my eye to Mary’s eye, I saw Faubourg Delassize and Livaudais unfold to the left, Tchoupitoulas Street and the hypnotic ribbon of the Mississippi River to the right. The city was electric at every hour, but at dawn, I was astonished by the wattage of color that vibrated in the silken light. Pink-, yellow-, and persimmon-painted shotgun homes stretched out in the Garden District, long and narrow as train tracks. Purple and green Mardi Gras parade beads and gray Spanish moss dripped from the branches of gnarled oak trees. I watched the streetcar roll up and down Saint Charles, passengers slowly climbing on and off as the metal trolley bell pealed through the air. Most fools imagine New Orleans as schlock and caricature—the tyranny of Bourbon Street and green terror of Jell-O shots. Throwing your guts up on the curb or into your crawfish étouffée. And, yeah, I’ve rolled my eyes at that nonsense in the French Quarter. But the city is more complex and hauntingly subtle than I ever imagined. Mythical and true.

As true as any story can be.

The intoxicating musk of sweet olive and night-blooming jasmine. Cobblestones the size of Bibles. The terrible symmetry of storms—the eyes and rainbands of hurricanes. Sudden downpours chainsawing the air. Floods and rebirth.

Across the city, I stumbled into random treasures, like divine visions, Saint Anne’s face in the palm trees. During my first week in the Order, after picking up my uniform from the Guild, I walked into a dusty curiosities shop, painted in the velvet black of a Dutch still-life painting, that sold only bird skulls, scrimshaw, and marbles. I’ve never been able to find it again. Through Mary’s portal, I watched peacocks roam the streets with the technicolor hues of an LSD flashback and envied their freedom. I saw fog hover like a neon white veil over the river and the corner shop on Magazine Street where Sister Therese learned you could buy one bar of soap and one vial of love potion for five bucks. She never brought the potion home, but her eyes sparkled every time she mentioned it.

Sometimes, as the quiet desperation of my breath settled on the stained glass, I wanted to run outside and join the spontaneous porch concerts that erupted at all hours—washboard jazz, bebop, zydeco, funk, punk, classical, swing. I wanted to pull a guitar out of a musician’s hands and play. To leave this earthly realm for a moment and let my fingers think for me. Sweat dripping from my chin.

But the Order challenged me to stay, to soften the barbs of my mortal coil.

Earth can be a heaven or a hell, depending on perspective. Control your thoughts, choose where to focus, and you can shift your reality.

Looking through Mary’s eye, I could see the four distinct buildings of Saint Sebastian’s campus. Our convent, church, and rectory were three standalone buildings closely grouped on the north side of Prytania Street. Our school, with its three wings—east, central, and west, arranged like a squared-off horseshoe—was across the street, due south. A grassy courtyard injected color and life into the center of the school’s U, between the east and west wings. Students lay flat as shadows in the grass under old palm trees, or they sat on the long granite benches, gossiping, swooning, doing anything but homework. A riot of flowers strobed in the courtyard all year. Even at night, their blossoms and orbs danced with their own fire.

Not that I was outside much carousing after dark. Without cars, the Sisters had to walk everywhere. In the lacerating rain, we walked. In the harsh sun, we walked. Through the punishing winds, we walked.

We had no computers in the convent. No cameras. No phones, except one corded green wall-mounted rotary relic in the kitchen. No money of our own. Our radio was a vintage model with a working dial, gifted by Father Reese. We bartered for goods like books, chicory coffee, red licorice, and Doritos (blame Sister Therese). We grew seventeen varieties of fruits, vegetables, and herbs in the garden, between the church and convent. No students were allowed in our garden, but once or twice I noticed Ryan Brown munching on figs and satsumas that looked rather familiar. Our eggs were from our own hens: Hennifer Peck and Frankie. When we had special Masses or post-storm fundraisers, we went house to house in our faubourg. That’s how I met a few neighbors, wondering and worrying what they made of a nun like me. Not that I knew what to make of a nun like me—gold tooth from a bar fight, black scarf and gloves concealing my tattoos, my black roots pushing through badly bleached hair.

God never judged me as harshly as I judged myself.

If you talked to anyone else the way you talk to yourself, Moose said, it’d be abuse.

Fortunately, there wasn’t much time to let my mind wander. When I wasn’t in Mass, teaching guitar, grading lackluster homework, or practicing with the choir, I cleaned, mopping the rich wood floor of our convent, carrying Murphy Oil Soap and warm water in a tin bucket, trying not to splash bubbles over the sides. I wore my white apron when I scrubbed, as Sister Augustine instructed. That way, we’d have a record of the dirt and grime, our toil, how hard we worked. We had to keep our facilities clean. Insidious wet penetrated every edifice, gnawing beloved structures from the inside out, like lies. All our buildings were drowning in mold. You’d bleach one corner, then notice mold blooming on a new wall the next day. Tarmac-black rashes.

Every Wednesday before dawn, I tiptoed around the convent in my slippers, with the telescoping duster, to remove the gothic cobwebs from our tallest corners. We never killed any kind of creature, appreciating the sacred energy of every living being, even faceless hell-things. Using a cup and newspaper, I carried centipedes, roaches, spiders, and giant moths outside to the garden and placed them gently under the orange blossom tree, the wasps hissing and thwacking against the side of the cup. Some spiders were big enough that I noticed their dozen eyes, glistening like iridescent black holes.

Freeing insects, saving souls—we did it all. Service meant action. Talk was cheap. Even the students were expected to pitch in. That Sunday, during my sweaty marathon of cleaning, I heard the heavy chime of the altar bell. It was Jamie LaRose and Lamont Fournet exiting the sacristy, their arms full of metal objects that caught slices of color from the windows’ prisms.

“Hello, Sister Holiday!” Lamont’s voice was as enveloping as a bear hug as he yelled from below. They were stowing liturgical gifts from Mass. “So sorry to bother you!”

I wondered about people who apologized for no reason, like they were currying favor for a future infraction. But Lamont and Jamie, both seventeen years old, seniors at Saint Sebastian’s, were the most reliable of our altar servers. Never late for choir practice. Never dropped the incense boat or backtalked Father Reese. Lamont was nearly six feet tall, and waxed loudly about his Creole family, crowned deities on the Krewe du Vieux float. Jamie was the quieter of the two, and stout, built like a bank vault. Always looking down and shuffling his feet. A definite heaviness about Jamie, smiled only with his teeth, never his eyes, like the kid kept his soul locked deep inside. He was from a Cajun line, French Canadians that migrated to the Gulf in whatever century. The boys’ surefire earnestness, their tucked-in shirts and desire to tell me everything about their young lives, was refreshing—unnerving, even—in the sea of teenage sarcasm and squalor.

After Jamie and Lamont left the church that Sunday, I finished cleaning in the sludgy heat and locked up. Made sure the courtyard and street were empty, avoided the procession to the imminent shitshow of a meeting, then I snuck into my alley. I called it mine because I was the only sucker who braved the clamor of the theater and the rotten stench of the dumpster. It was my secret.

Everybody’s got secrets, especially nuns.

Like a good mystery, the alley was both hidden and obvious. You could walk right by it and never see it. A gap by design. My secret smoking lounge. And, that day, my front-row seat to the crime that would change everything, the first rip of the unraveling.

I had no money for cigarettes, of course, but smoking what I confiscated from my students was fair game. Students aren’t allowed to smoke at Saint Sebastian’s—it was my duty to step in. And Sister Honor says waste is a sin. So, there I was on my stoop in the alley on Sunday night, minding my own business, roasting in the delirious heat that never ceased, not even at dusk. Django Reinhardt guitar spilled from a car somewhere on Prytania. Music was the connective tissue of New Orleans—there when you needed it, like prayer. Both prayer and music were holy, and they saved my sorry ass more times than I could count.

A true believer, me, despite the optics.

That’s why Sister Augustine positively welcomed me to Saint Sebastian’s School last year. She saw my potential. She was the only one who gave me a chance when no one else would, not even the daycare where they employed security guards too rough for correctional facilities, or the auto repair shops where everyone was on meth, or the insurance agencies in Bensonhurst. I was willing to work nights and weekends, for fuck’s sake, and I had the makings of a damn good investigator: equal parts methodical focus and capriciousness with the patience of a hunter and an appetite for femme fatales. They still said no. But not Sister Augustine. She invited me to New Orleans, into the Order, with a few provisions.

There were only four of us: Sister Augustine (our devoted Mother Superior), Sister Therese (a former hippie with a resting beatific face who fed stray cats), Sister Honor (an interminable killjoy who detested me), and me, Sister Holiday, serving the impossible truth of queer piety. We were as different from one another as the book of Leviticus to the Song of Songs to the Book of Judith. As an Order, though, as the Sisters of the Sublime Blood, we made it work. For God’s love—the only real love—and for the sake of the kids and our city. Our motto, Toshare the light in a dark world, is carved into the plaque on our convent door.

We were a progressive Order, but Catholic Sisters all the same, with rules to follow or, in my case, to test. We were focused, working diligently at the school, the church, the prison, and our convent. Our bedrooms were modest. Our convent bathroom was spartan and cavernous with a musty, sepulchral air. No mirrors anywhere. No blow-dryers. The shower stalls sported cheap plastic curtains. When I spaced out in the shower, never for too long (Sister Therese timed me to preserve water), I’d watch droplets form little stalactites on the ceiling. The convent’s common areas were as austerely appointed as holy tombs, and as cold, a blessing in the sweltering, insistent heat.

Even my shady alley was blazing hot. I had my goddamned gloves and scarf on that Sunday, as Sister Augustine demanded, and it felt like they had melted into my skin. It was still a glorious moment alone, before the staff meeting adjourned, before I stepped into the convent for supper, with two cigarettes collected on Friday afternoon, nabbed from behind Ryan Brown’s pointy ears. “Aw, Sister, again?” Ryan Brown, a sophomore at Saint Sebastian’s, the king of self-owns, whined after I took his smokes. “C’mon.” He threw his hands in the air like a toddler. Of all my students, he had absolutely no street smarts. My contraband supply flowed through this curious kid. Most students fled the instant I walked into a room, whereas Ryan Brown lingered. His flagrant violations of our tobacco rules made it seem like he was trying to get caught. Or he was bad at being bad. Not like me.

I held up the cigarettes. “Showing off your smokes makes you a tough guy?”

“But I—”

“Learn how to fight for what you want,” I cut Ryan off. No time for excuses. “Or learn how to hide it better. Otherwise, you’ll lose everything.”

My wisdom held a kind of grace, I’ll admit.

I offered my students the only thing that mattered in life—honesty—and I served it the way I meted out revenge, ice cold. I was a fuckup about most things, but when it came to commitment, I was all in, like a python eating a goat, sinew and toenails and skeleton and all. Like my Sisters, I did everything I could to lift each student, to help them carry the light in their own hands, not hold it for them. Sometimes that meant calling out their sloth and turpitude. And I knew how to clock BS because I lived it. To break a horse or a human, you must first understand wildness.

All weekend I had waited for the perfect moment to savor the cigarettes, and it had finally arrived that Sunday. I was sweating through every layer of my uniform, but I needed more time outside. Without a minute to myself, I’d snap at Sister Honor. My fuse was still dangerously short, and Sister Honor knew how to wind me up.

I pulled out one of the stolen cigs that I kept hidden in my guitar case. Ran it under my nose, sniffed it, and lit it with the last match in the book. A cloud of gnats dispersed as quickly as it formed, not like the sunset, which remained, the battered gold of a pocket watch that seemed to slow time itself. Twilight was the hinge between day and night. Gauzy tides of heat pushed and pulled me. My skin pruned under my gloves. They say if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere. But New Orleans is the crucible. The home of miracles and curses—neither life nor death but both. In such a liminal space, like standing in a doorway, you could be in or out, doomed or redeemed.

Sweat rained down my back. I was surprised it was so quiet out there, in the moth-thick alley, no live show or rehearsal in the old theater. putting the devil back in vaudeville, the poster promised. Like the devil would let anyone tell them where to go. The theater, like so many grand spaces in the city, was devastated by the storms that grew stronger every year. Paint on the front door peeled off in big mahogany rolls. On route to ruin, still delicious. More opulent than Buckingham friggin’ Palace.

With all the matches gone, I had to chain-smoke my contraband, lighting one with the other. Such luxurious tobacco—probably an import. Our wealthiest students were fuckers—I’m sorry, Lord, it’s true—but their smokes were superior to the garbage I choked on back in Brooklyn, back in my old life where my fingers bled for rent money, for tips, for my next whiskey.

A crescent moon floated like a talon. Frogs croaked in the privacy of their night disguise. A creaky chorus, the nocturne. Ever more haunting in the tropical steam and amber smoke of the streetlights. Meaty magnolia blossoms held glinting veins of pink, little hearts pumping inside each petal. I took another drag, let it sink in.

Suddenly, the back of my throat soured. My eyes watered as a wave of extra heat slapped me.

Then, a smear of red and orange. The night sky exploded. It took a beat to understand what I was seeing.

Fire.

The school. My school on fire. The east wing of Saint Sebastian’s was burning.

Livid flames stabbed through an open window.

In a few seconds, the horror erupted. That’s how it feels—the fastest slowest moment. Anything so unexpected warps time, with wretched clarity and blurriness. Like a car accident. Like your first kiss. The tiniest details at once magnified and obscured.

A flaming body dropped from the second floor of the burning east wing and pounded the ground like a vicious fist.

“Dear God.” I dropped my cigarette and tore from the alley across First Street, to the person in the grass. “Help!” I screamed, but nobody was around. Breathless, voice clipped.

Jack. It was my cleaning confidante, dead.

“Jack!” I knelt by his side. “Oh my God.”

He didn’t blink or flinch, just smoldered. A thin line of blood trickled from his right nostril, so delicate, like it was painted with care by a rare brush.

Jack charring in the grass, his limbs splayed—the devastating choreography of a stomped roach. His burnt flesh smelled acrid and terribly sweet.

Did he fall through an open window, trying to escape the smoke?

Was he pushed?

Lord, hold Jack close.

The doors were always locked after the staff meeting, which ended more than an hour ago, the meeting I skipped.

Help.

I thought I heard a cry from inside. I had to be certain the building was empty. The door handle was not yet hot, so I placed my short scarf over my mouth like a bandit and unlocked the door. Smoke blasted into me.

“Hey!” I sprinted down the hallway screaming, coughing. A peculiar strength led me forward. “Anybody here?”

Plumes of smoke crab-crawled sideways across the ceiling. Ashen tendrils dripped through seams in walls, silent as breath.

The fire alarm was stiff. Old red paint flaked off as I tugged at the lever. I cursed at it, as if that would help. It finally budged and clicked down, sounding a shrill alarm that would shake the dead. But no sprinklers activated.

“Anybody here?” My throat was raw.

“Help!” someone yelled in the distance. It felt simultaneously far away and right in front of my face, but I could barely see. “We need help!” It was a familiar voice, but I was so panicked I couldn’t place it, like a song in fast-forward.

The smoke smelled like hot garbage as it spun me. Like in Brooklyn, the night of ignition. The night my old life ended.

Nothing was in its right place. No one should have been inside. “Keep talking! I’ll find you.”

The air was cement-thick, but I saw movement—someone at the end of the hallway.

“Hey!” I choked as I ran toward them, sliding over a sharp puddle of broken glass. “Hey.”

The shadow elongated then vanished in an instant with the clean, continuous lines of a fish in motion. A blessed spirit. Been waiting my whole life to see the Holy Ghost, and it had to be here? If bad timing was a religion, I’d be the pope.

The cries amplified behind me. I snapped around, tried to follow the voices. The door to the old religion classroom was open and inside the room, squashed on the floor, were Jamie and Lamont. Why were they there? What did they see? What did they do?

I ran to them.

“He’s cut!” Lamont pointed to Jamie’s leg where blood flowed from his thigh. “My ankle broke or something.”

Both boys were sitting side by side under the chalkboard. They looked like kindergartners preparing for story time, save for the furnace of fire and smoke, and the blood pouring out of Jamie’s leg. A wedge of broken glass, the size of an open hand, stuck out of Jamie’s thigh. The shattered transom I skated through in the hallway. He squirmed as he held the outsides of his left leg. His blue eyes raged as he howled.

“I’m carrying you out.” I knelt. “Lamont, throw your arm around me. Jamie, next. Did you see Jack up here?”

Neither boy answered, frozen with shock. Or was it guilt?

I tried to carry them both but could barely lift an inch before all three of us slumped back down with a horrid thud.

Jamie roared. The glass in his thigh must have lodged deeper.

If I tried to carry them again, it could get even worse.

The workings of the body were as mysterious to me as the mind, but even I knew I had to stabilize Jamie’s leg. “One, two,” I said, and on “three,” using my glove for traction, I pulled the blood-slimed glass out of his thigh. Bits of him remained on the glass, on my gloves. He screamed like he was getting carved alive by a butcher.

Lamont sat helpless, trying to comfort a gnashing Jamie as blood spilled down both sides of his pulpy thigh.

Hail Mary.

Nothing prepares you for the cruel wet red of an open wound. A second mouth. Demonic.

I prayed, tried to channel Moose.

Praying is schizophrenic, Moose’d say to piss me and Mom off. You’re talking to nobody. I pleaded with him not to join the army, the way he begged me not to join the Order. Like it did any good. Reverse psychology was a family practice. I joined the convent and Moose signed up for combat medic training on the very same day. We traded old lives for new lives like it was a simple or silly thing, easier than making a quarter disappear. Stagecraft. Who’d ever think the queer-ass Walsh kids would become a nun and a soldier. Ta fucking da.

I ripped off my scarf—the thin cloth Sister Augustine made me wear—and tied it tightly around Jamie’s thigh. A quick tourniquet. “I wish I could carry you both, but I’m taking Jamie out first—he’s lost so much blood.”

“Don’t leave me!” Lamont cried; his brown eyes were bloodshot, leaking fear.

I tightened Jamie’s tourniquet, placed his left arm around my shoulders, and lifted him from his waist. “Up!” Like a drunk couple on a cheap jazz honeymoon, we hobbled as one being. Jamie was taller than me, solid muscle, but I lifted him enough to walk.

“I’m coming back, Lamont. Swear to God.”

Adrenaline thundered through my veins, like the uppers I used to snort, like the divine surge of Godly strength in the parables I came to love.

Hail Mary, Mother of mercy, our life, our sweetness, our hope.My third eye.

I kept us limping into the hallway. Lamont whimpered on the ground, dragged himself like a seal after us, crying out for me, for God. Blood powered out of Jamie, making quick work of my shitty attempt at a tourniquet. It would have been aces if the Holy Ghost delivered a miracle right then and there, but we couldn’t wait for divine intervention.

A flaming ember shot into my left eye—“Fuck”—like a bayonet landing in my cornea. The awful precision of what cannot be controlled.

We staggered to the stairwell. Momentary lee from the smoke, a small prayer answered. That’s where I saw Jack’s ladder and toolbox. The janitors did most of their cleaning and tinkering at night, but on a Sunday?

Did Jack start the fire? The boys? None of this made sense.

But it never does. Twice now I’ve stared Death in the eye. I know it’s gunning for me. For all of us. If I can keep outrunning it, I will.

Jamie’s eyes were open, but his gaze was blank, the resigned look of someone who’s given up. I slapped him hard across the face. “Focus,” I said, even though my mind was running in ten directions. I thought we’re fucked! and we’ll make it! at the same time, and I needed to know what the boys knew. I drilled my tongue into my gold tooth, hard enough to draw blood. It was a nervous tick, but it grounded me, a secret covenant, invisible to everyone but me and God; it helped point me ahead.

As we reached the ground floor, a different alarm began to shriek. The tall, heavy emergency fire doors of Saint Sebastian’s east wing started to swing slowly.

The automatic doors were locking us in.

“We’re getting out of here.” I surprised myself with the jolt of energy the word we imparted.

I kicked my foot into the main door, one breath before the magnetized fire doors sealed the east wing shut.

Holy Ghost, don’t leave us.

I grunted as we staggered outside, where school papers and ash rained. Jack Corolla’s body lay perfectly stiff near the east wing’s entrance. A now-empty shell that had once held everything that made Jack Jack—the talking-with-his-mouth-full, the walrus laugh, the nervous energy. Jack’s spirit vanished.

Jamie, barely conscious, murmured, “Is that … a body?”

The wail of police sirens, ambulances, and fire engines shook me. A fire truck slowed then stopped in front of us as we wobbled. Firefighters leapt off, unraveled their orange hoses, and ran to the blazing school.

Jamie collapsed on the ground, his eyes closed, mouth hung open as if in a deep, sloppy sleep. Paramedics rushed. Seeing that mangled, bloody kid in their capable hands was such a relief, almost unbearable. Thank you, Lord.

“There’s another student inside!” I yelled with my sandpaper tongue. “Lamont. He’s hurt.”

“Where?” asked a medic.

“Second floor, street-side. Jack fell through the window.” I turned around and pointed to Jack’s body in the grass. My hand, as I lifted it, felt like carved marble.

A woman with a badge appeared and helped steady me as I started to fall. For a lightning-quick moment, we fell together. But she posted her legs, straightened her back, and flexed her arms to keep us both upright.

“Chill Sunday night, eh,” the woman said with a smile that lifted higher in one corner, like a capsizing ship.

“I have to”—I choked—“inside.” I couldn’t string words together.

She tightened an iron grip around my bicep. “Nah. We’ll take it from here. You’ll be less dead outside with me.”

The woman’s ID was clipped to the left chest pocket of her wrinkled blouse—Fire Investigator Magnolia Riveaux, New Orleans Fire Department. “Keep breathing. I’m Maggie.” In the ambulance headlights, her face glowed with sweat. “You hurt?” she asked, knowing the answer.

“Cinder in this eye.”

“We’ll get that flushed out.” She walked me toward an idling ambulance that had parked in the courtyard. The EMTs were creating a staging area.

“You saw the fall?” she asked. “I hear that right?”

“Jack Corolla.” I coughed, and when my lips smacked, I realized they were chapped from the heat. “Don’t know if he jumped or was escorted out or what. Jack’s our custodian.”

She swiftly lifted her two-way radio, pressed her lips against the perforated surface of the mic. “217 to Dispatch.”

“Go ahead, 217,” said the voice in the radio.

“Got a witness”—Investigator Riveaux locked her eyes on me—“what’s your name?”

I opened my mouth to talk but no more words came. How enraging to be silenced by my own body.

“Lungs might be scarred here,” she told the invisible radio person.

The night air was thrilling and sickening, like a gulp of swamp water. That was the marshy taste on my tongue as I passed out. My body turned to goo, and I slipped through her grip.

■

When I woke, I was surprised to feel the elevation of a gurney. The plastic cup of an apparatus covered my mouth. The oxygen was smooth and glorious, did the breathing for me.

How long had I been out? Where were Jamie and Lamont? Each second held complex layers—imbricated as gills. Screams, cries, relief, prayer, fear. My black polyester trousers, my uniform, seared into my skin. Gloves long gone.

Somehow, my gold necklace hadn’t broken, my cross still pressing its weight against my chest. My blouse, torn and loose on my shoulder, slipped, revealing my ink. Tattoos extended around my neck, above my jawline, to the base of my skull. Buttons must have popped off as I carried Jamie. Riveaux’s eyes narrowed as she studied my exposed skin, tracked my tattoos. lost and soul were inked on my knuckles. On my throat was Eve holding her apple. The palindrome deified was drawn in glittering green and gold cursive, ominous opulence, like the snake in the garden of Eden, across my chest. It was my most painful tattoo. A reminder of the price of selfishness, of what’s at stake when you think only of yourself, no matter how good it tastes. It was also a favorite because I could sort of read it in the mirror. Not that we had mirrors in the convent. Riveaux mouthed the word deified—she was reading me or trying to.

I covered myself with the stiff blue blanket the medic had given me.

“Nice grille.” She pointed at my gold-capped tooth with her bony finger.

I bared my teeth like a dog. Lifting my lips was exhausting.

“217 to Dispatch.” The investigator pressed the receiver to her mouth again. She said, “Arson. No doubt.”

Arson. How could she know so quickly? What was the tell?

Riveaux looked into my good eye. “Name again?”

“Holiday Walsh. I mean, Sister Holiday.”

“Sister?” She was stunned. “I thought you were the school’s death-metal lunch lady.”

“I do feel dead. The boys okay?”

“Badly injured,” Riveaux said, “but they’ll be all right. Once they’re stable at the hospital, I’ll give them the third degree.” Her puns were stellar only in their consistent miss rate, yet she seemed pleased with herself. Riveaux’s eyes gleamed with purple and wood, the moody light of a sun storm.

Searing hot, I needed to feel cold ground underneath me. When Riveaux got pulled away by the fire captain, I slipped out of my mask, rolled off the gurney, and crawled onto a patch of crabgrass. In front of me were scattered worksheets and test papers and a small wooden cross on the grass. One section of the cross was scorched, burnt down to the stub. It looked as if it could be carried easily, like a gun. I wanted to hold it close. I reached for it, but an EMT scooped me up, his strong hands under my wet armpits.

Back to the stretcher.

Riveaux and a medic watched me as I lay down in the ambulance. The oxygen mask was placed back over my nose and mouth. They were monitoring me closely. I choked trying to catch my breath, drowning in my own body.

With the adrenaline burned off, I felt it, the battle—angels, devils. I saw Death and survived the flames twice now. No need to read the Bible to learn how the elements torment and sustain us. Fire, anger, water, redemption. What plot twist sparked it, the arson? I’d figure it out, eventually, or die trying. Sleuthing and stubbornness were my gifts from God, tools They knew I could use. Yes, my God is a They, too powerful for one person or one gender or any category mere mortals could ever understand. That day, God and the Holy Ghost opened the door, and I ran into the flames to help the boys. We were in the fire, inside its red-purple grip, the rhythmic walls of a beating organ. But it was equally obvious, lying there on that gurney, half blind, half alive, that no person nor saint nor psalm would save me. I’d have to do it myself.

2

DUSK SHIFTED INTO NIGHT as I waited in the back of the open ambulance. After scolding me for removing the glass from Jamie’s leg—“never, ever do that!”—the medic repeated “calm down” as he took my vitals, but I kept sitting up on the bleached white sheet of the stretcher to watch the flames.

The fire’s refusal. Its ease. How closely our world is nailed and joined together, how quickly it can all ignite.

Firefighters blasted the east wing with serpentine hoses. Water made the flames bite back. I blinked, scanning the dark courtyard for the Holy Ghost, but I could hardly see. My eye itched, like it had been stung by fire ants.

After picking their way through the crowd from our convent across the street, my Sisters formed a half-moon at the ledge of the ambulance.

In their veils, Sisters Honor, Augustine, and Therese could have been figures in a daguerreotype from the last century. They were the only nuns in New Orleans who wore the traditional habits, long black tunics like tents. Gold crosses. A full mood.

Sister Augustine raised her arms to the choking sky. “Lord, have mercy.” Phrases people say every day with irony or humor, but to us, the words are as real as blood. No different than a witch’s spell. Our principal’s voice was grounded, and though her blue eyes were clear, she had to readjust her habit, regain composure. Wipe beads of sweat.

Even a saint could fall apart, not that Sister Augustine was a saint, but she was so restrained, I sometimes forgot she was mortal.

“O Holy, Holy, Holy Lord,” recited Sister T in her musical voice, “guide us.” She had the olive skin and respectable face of my Aunt Joanie, a face you trust because it’s plain. Her back hunched, a signpost that the woman was inching toward eighty years old. But she was tougher than she looked. Sister T could move great stones in the garden and pick up a barrel of rainwater by herself.

As unremarkable as announcing the time, I said, “Jack’s dead.”

Sister T stacked her small hands over her heart and looked at me with the worried eyes of a mother cat. “You saved Jamie, Sister. And brother Jack’s soul has an eternal home.”

Yes. Jack is gone, but he’s safe. He’s free.

As long as he didn’t start the damn fire. If he did, his forever home will blaze eternally.

Sister Honor had been covering her mouth with her puddy hands, then she spoke: “How could you leave Lamont inside?” She shook her block of a head and sucked her teeth.

“Hush now,” Sister T pleaded. “How could she possibly carry two boys at once?” She blessed herself.

A swell of guilt made my flaming chest and face even hotter.

My heart seemed to stop beating for a second. Moose, I’mhaving a heart attack.

No, you’re not, I imagined Moose correcting me. I could hear and see my brother schooling me, a queen when he wanted to be, but always with the kind eyes of a husky puppy, appreciating each syllable as he uttered it. What you are experiencing isa panic attack.

Riveaux and a medic shoehorned their way through the tight arc of my Sisters. The medic had mercifully cold hands and a dimple the size of a jelly bean. He irrigated my eyes and placed a patch over the burnt one.

“Liking that eye patch. Shiver me timbers,” said Riveaux. She was a married-to-her-job type, judging by her unironic mom jeans, split ends, and shapeless blouse with all the je ne sais quoi of an airport bar. Sopping sweat marks drenched her armpits. Her metal-framed glasses were two sizes too big for her narrow face. She shone a flashlight for a better look at me.

Who was this woman? Her bad jokes. Her bad jeans. Why wasn’t she leaving me alone?

Neighbors, students, and news reporters huddled in the street between the church and school. One reporter zipped up on a motorcycle and started filming before she removed her helmet. Clumps of red rhododendron nodded with the crowd’s percussion. I spied the noodge Ryan Brown taking photos with his phone, close to the staging area in the courtyard, until he was shooed away by cops. The Sisters broke their ambulance formation, moving in a wave of black, an unkindness of ravens, swooping in and leading Ryan Brown across the street to pray.

In the ambulance, Riveaux’s radio hissed with voices. Cryptic codes, cross talk.

A half hour had passed since I brought Jamie out. The entire second floor of the east wing was engulfed. The epileptic strobe of emergency lights hurt my unpatched eye.

The dimpled medic prodded me on the gurney. I was too weak to swat him away. “Pulse oximetry, okay.” The medic took my blood pressure, listened to my heart. “Blood pressure, 90/60. She’s pushing it, but at the edge of normal.”

The courtyard buzzed with the hustle of a field hospital. Another police car parked near a shabby red pickup truck, which I’d later learn belonged to Riveaux. The bumper was falling off.

I sucked the soft air of the respirator, ripping the mask off every thirty seconds to cough. I needed to spit—soot coated my teeth—but my mouth was too dry, my tongue like gravel. It was a well-worn feeling, the trauma of filling my body with poison, pushing every inch of myself to its absolute limit. Moose used to say people like us start smoking so we can have excuses to take deep breaths. He was right about that too.

“Punch me in the stomach,” Moose said years ago, after his attack. “Punch me as hard as you can.”

“I’m not going to hit my baby brother.”

“Do it.” He took my right hand and balled it into a fist. I wasn’t used to callouses on his normally fine hands. His fingers were usually more elegant than my scarred digits.

“No.”

“I need to get stronger. Punch me.”

“No.”

“Punch me.” Moose closed his eyes. “Do it.”

So I did. My brother asked me to punch him—to hurt him—to help him heal, so I drove my tight right fist into his belly and felt his soft flesh separate. He groaned as I made contact. The strange elixir of hurting someone, being good at making something hurt.

Riveaux’s voice pierced my internal smog. “Any staff, yourself included, or students have a history of arrests or arson?”

I had been nearly arrested in Brooklyn, more than once. But thanks to my old man, a longtime copper, I was never charged. I omitted those factoids.

Sister Honor rematerialized and chimed in. “Prince Dempsey!” She pointed to Riveaux. “Write down P-R-I-N-C-E D-E—”

“Mm-hmm,” said Riveaux, terminating the spelling lesson. “What’s Prince Dempsey’s story?”

“A troubled student,” I said. “Talks a good game but he’s just a petty vandal.”

“This we do not know, Sister Holiday!” The plush fury, the theatricality of her words, everything out of Sister Honor’s mouth was scripture or Shakespearean sonnet.

She was right, though. Prince Dempsey was a wild card. “I don’t know,” I said, which was honest. “Prince rescues dogs,” I added, “but he’s terrible with people.”

Sister Honor shimmied her shoulders and fussed with her veil as sweat slalomed down the creases of forehead. “Well, Prince Dempsey started two fires last year, right here on campus.” She had the staccato rhythm of someone trying to keep it together, to quell tears before they started again.

“Firebug. Interesting.” Riveaux scribbled in her steno, squinted at my tattoos again, then turned away from me to talk into her radio. More codes, fire words. Terminology I didn’t understand.

What I did understand was body language, and the way Riveaux and Sister Honor were both looking at me, almost as if they suspected I had some role in the fire. Or Jack’s brutal fall.

I’d have to solve this puzzle myself, if only to prove everyone wrong.

Riveaux moved between the ambulance and the edge of the burning wing. Each time she returned to the vehicle, she seemed more convinced. Of what I didn’t know.

All three of my Sisters were well into their golden years, but now back from their prayer circle, none of them asked for a chair or to make room on the ambulance ledge to sit.

Sister Honor’s cheeks sagged as she looked at the burning wing. “Look upon our sorrows, O powerful Lord.” Cavernous wrinkles surrounded her eyes. I watched tears carve her face. “Sister Holiday,” she barked, “what in the good name of our Lord are you staring at? Stop making a mockery of my grief!”

What, I thought, makes you despise me so much? I felt my disdain for Sister Honor—or was it fear?—on a physical level as it cascaded through my chest and head.

Forgive me, Lord. I am trying to be better.

With me on the stretcher and my Sisters below on the ground, it was like I was on stage. Sister Augustine smiled. Being near her was a somatic comfort, the pendulum that sets the rhythm. She took a long breath. “The Lord is our Shepherd. We will be okay.”