Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

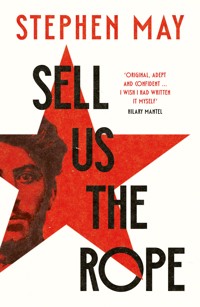

'A deeply satisfying novel. Incisive, inventive, frequently very funny' Guardian 'Historical facts furnish May with a cast of legends to bring to life, and he does it with verve and humour' The Times 'Original, adept and confident ... I wish I had written it myself' Hilary Mantel When it's time to hang the capitalists, they will sell us the rope. May 1907. Young Stalin – poet, bank-robber, spy – is in London for the 5th Congress of the Russian Communist Party. As he builds his power base in the party, Stalin manipulates alliances with Lenin, Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg under the eyes of the Czar's secret police. Meanwhile, he is drawn to the fiery Finnish activist Elli Vuokko – and risks everything in a relationship as complicated as it is dangerous.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Sell Us the Rope is original, adept and confident. What can I say, except that I wish I had written it myself?’

Hilary Mantel

‘Stephen May has always been endlessly inventive, but with Sell Us The Rope he has entered a whole new literary realm. A rare achievement.’

Benjamin Myers

‘Stephen May’s writing is engaging in this brilliant tale of revolutionary shenanigans in London.’

Suzanne Joinson

‘Boldly conceived, precisely imagined, beautifully written.’

Michael Stewart

‘Electrically-imagined, immersive and compulsively readable. Hums with revolutionary fervour, Machiavellianism and sex in turn-of-the-century London.’

Liz Jensen

‘A brilliant and original blend of genres. The book cunningly mixes fiction with non-fiction, yet all its most far-fetched details turn out to be true.’

Marcel Theroux

‘Stephen May is masterful at packing a powerful emotional punch with great subtlety and dark humour. This book really got under my skin.’

Katherine Clements

‘An addictive novel about the juicy aspects of being human: love, betrayal, power and control.’

Lisa Harding

‘In this quietly menacing novel, Stephen May depicts the early stirrings of the monstrous, inhumane machinery of totalitarianism.’

James Robertson

Stephen May is the author of five novels including Life! Death! Prizes! which was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award and The Guardian Not The Booker Prize. He has been shortlisted for the Wales Book of the Year and is a winner of the Media Wales Reader’s Prize. He has also written plays, as well as for television and film. He lives in West Yorkshire.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

TAG

Life! Death! Prizes!

Wake Up Happy Every Day

Stronger than Skin

We Don’t Die of Love

To Nile Spark

SWIFT PRESS

This edition published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2024

Originally published by Sandstone Press 2022

Copyright © Stephen May 2022

The right of Stephen May to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Typeset by Iolaire, Newtonmore

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800754638

eISBN: 9781800754645

One of the blessings of Freedom is that of harbouring unwelcome, or at any rate, unbidden guests. The Russian revolutionaries, forbidden to hold a Conference in Denmark or Sweden are sailing for England, where they will discuss matters without any fear that the Government will think it worthwhile to interfere . . . – The Globe, London, May 8th 1907

1

How Can Anyone Live Like This?

10th May 1907

Morning of a damp day when the ferry from Esbjerg bumps knuckles with the quay at Harwich. Three men descend the gangplank slowly, carefully. It has been a restless journey. A choppy sea and too much strong Danish beer. Too much singing.

On the glistening quayside now the men from the boat sigh, straighten stiff backs and try to keep their feet on slippery flagstones. They attract the eye, these men. Koba – you know him as Stalin – is small and wiry, his face pockmarked, dark hair dishevelled, eyes burning from beneath a perpetual frown. Stepan Shaumian is taller, more at home in his body, his mouth more generous, more inclined to smile. They could be artists or actors or itinerant musicians. They have that kind of dangerous shimmer.

The third man, Mikhail Tskhakaya, is older, body fleshier and hair greyer, but you can still see a boyish idealist’s face beneath the well-trimmed beard and the lecturer’s spectacles.

Koba is the most energetic of the three even when not moving. His leg twitches, pulsing to some internal music. His agile, crow-like face stares around impatiently. He slaps the tramp steamer soot from his trousers. Takes it all in: these looming grey warehouses; these chests full of fat pink shrimps; these coils of wet rope. This litter of unattended barrels and boxes. This stench of rotting fish and tar. These listless horses, plodding past the barges and the pleasure steamers. These children giggling at nothing who should be in school.

He hasn’t written poetry for years, but he has tried to retain a poet’s eye.

Behind them, the porter drops their cases noisily. Clears his throat. They turn and murmur indistinct thanks. Koba pays the man and sees immediately that he has overdone it again. Sees it in the way the surly fellow brightens. A sudden grin transforms his face. The rough verge of his moustache seems to cakewalk on his thin lip. Koba knows he has to stop doing this. The budget is two shillings a day, nowhere near enough to be acting like some millionaire, like some bloody hertsogi.

There is the need to say something.

‘Har-witch,’ he says, flicking the strange syllables from side to side in his mouth. ‘Har-witch.’

‘Harridge,’ Tskhakaya corrects him quickly. ‘It’s pronounced Harridge.’

Koba scowls. Tskhakaya shouldn’t have done that. Koba will have to find a way to put him in his place now. His brow corrugates but he says nothing. Strokes his dark moustache.

Thing about Tskhakaya is that he is too much the teacher, too much in love with his own knowledge, tone-deaf to the feelings of others.

He compounds the error. ‘Time for a little stroll through the town,’ he says in English.

English! Another little dig. Koba speaks the most basic English of the three of them. He can muddle through, but languages aren’t a strength. Not much French either and he didn’t even speak Russian until he was nine.

‘Let us meander towards the railway terminus. Meander – such a beautiful word, don’t you think, Josef?’

This annoys Koba too, the way Tskhakaya won’t use the name he has chosen for himself, the name he took from the great hero of the old stories. Koba the gmiri, the poor man who showed true nobility by defending the weak against the strong, who robbed the rich to help the poor, the outlaw who brought justice.

Tskhakaya speaks again, in Georgian this time, ‘Come on now Comrades! London awaits!’

Such an arse.

The revolutionists walk from the quay to the station, past scuttling citizens who barely glance at them. Places to go, people to see. Fish to buy. Harwich is a place proud to call itself a town of hurry and business.

They walk past the Alma Inn, where a sign proclaims that wholesome pies and other refreshments can be had at short notice; past the British Flag where a former landlady drowned in the cellar as the estuary surged one stormy January; past the Angel, so-called because it was once – not so long ago – the haunt of child prostitutes. They saunter past the spot where last year an abandoned baby was ripped apart by starving street dogs. Every town, however small, has its horrors after all.

They skirt around the knots of men outside the Packett Inn, the Duke of Edinburgh and The Little Eastern.

‘England has so many drinking holes,’ says Shaumian. ‘A nation of drunks.’

They keep their heads down as they pass The Elephant, where the soldiers of the garrison like to meet, and sometimes fight with, the sailors of the naval base.

Koba leads the way, striding ahead. He does not meander. He looks hard at the people around him as he marches on – that poet’s eye – but he is uninterested in discussing what he sees.

Of course there is also something that only Koba sees. The shadow that flits from doorway to doorway, always at the very edge of his vision, disappearing if you try and look at it directly. A presence still barely perceptible but growing stronger, more definite, with every passing day.

A smoky third-class train journey. Smuts in their eyes. The smell of cheap coal seeping into the folds of their clothes. Taste of soot in their mouths. Trying to get comfortable on crowded wooden benches, staring silently out of smeared windows as they are rattled through small, flat fields. Cabbages and sugar beet and potatoes. Fat cattle. Thin horses. Sweet tea bought from a cheerful railway worker pushing a cart along the corridor outside the compartments. He wears a stained blue uniform in heavy serge as if he were a military man back from some bitter campaign overseas. He looks the men up and down in an insolent way. He says, ‘Up the Workers!’ and laughs as he slops his wheat-coloured brew into whitish china cups. He adds milk without asking whether they want it and lurches down the corridor coughing and leaning heavily on his trolley.

Tskhakaya and Shaumian discuss whether this man will be supporting the English railway strike due to start next week. They are inclined to doubt it.

Shaumian asks Koba what he thinks.

Koba stares into his tea cup. ‘I think I can’t drink this grandmother’s piss.’

Ninety minutes later the men stumble into the suffocation that is London. They have heard about the city’s wet black fog – everyone has – but the reality is something else again. As Shaumian says, this fog is like gravity, it’s like being pressed into the ground by many heavy hands on your head and on your shoulders.

‘Like being pressed into shit,’ says Koba the poet. ‘Like being drowned in other peoples’ faeces.’

It is true that the cobbles are treacherous with excrement. There are a million horses in London pulling carts, carriages and hansoms. Each one drops many pounds of dung every day. Then there are the cattle swaying gently on their way to market or slaughterhouse, the clinker-blackened sheep, the pigs who, sensing their final destination, squeal and fight in savage protest, the dogs yelping excitedly around the wheels of the carts. All of them urinating and defecating and no one clearing it up.

Here and there in this shallow ocean of manure are spooled little islands of human turds. It makes their stomachs turn. There is no stepping around this filth, either, there is just too much of it for that. And there is absolutely no escaping the smell, which chokes and strangles, leaves you gasping. The whiff of sewage, but also of tanneries, breweries and dyers. Textile mills, leaky tanks of town gas. Decaying offal. Underneath it all the sickly-sweet odour of unwashed human bodies. Every step means feeling your way through a thick noxious soup.

Then there is the noise. The engines and the motors, the clanking orchestras of machinery. The bells of churches and ambulances, the thump of hammer on anvil in the blacksmiths’ workshops, the hollow rumble of the underground trains beneath your feet.

Human sounds too. The wild jigs of musicians, the bawdy refrains of the ballad singers, the cries of the hawkers and the beggars.

How can anyone live like this? How do they stand it?

The people of London seem unbothered. Maybe they have other more pressing things to worry about. The wide haunted eyes, papery skin and distended bellies of the children suggest that they are just too hungry to notice irrelevancies like stink and uproar. Nothing on their minds except food. As Shaumian says, if you fall down here these mites will be on you like rats or piranha fish, stripping the flesh from your bones with their sharp little teeth in seconds. You’ll be finished before anyone has time to pull them off.

From time to time they pass policemen impassively watching the crowds. Even accounting for their tall helmets and heavy capes, it’s clear that they are bigger and stronger than most of the people flowing around them.

‘Farmers’ sons,’ says Tskhakaya knowingly. ‘Fattened on meat and eggs and brought to the city to defend the property of the bourgeoisie and to intimidate the working class.’

Twenty minutes’ walk from Liverpool Street station the men approach the narrow streets of Whitechapel, where the square boxes of the houses become smaller and where the pavements are even dirtier, even more crowded, yet the Georgians begin to feel a little more at ease. They now hear languages more familiar to them than English: Russian, Polish, German, Yiddish, Hungarian, Turkish. A lively choir of almost intelligible words. They begin to see people who look like they do too. Bright-eyed, raven-haired, argumentative people in dark clothes. Men and women who are raucously alive unlike these sickly English wraiths they move among. There are still plenty of pubs but there are also cafes and eating places of all kinds and from all corners of the earth.

The three of them stop to buy gefilte fish from an Armenian street seller. As they eat, Tskhakaya tells them that in these East London rookeries there are 120,000 Jewish refugees from the pogroms, among them many revolutionary Socialists.

‘Of course there are also gangsters,’ he says. ‘Jewish gangs and Slavic gangs, sometimes working together, sometimes engaging in bloody feuds. Boys skilled in the arts of blade and garotte.’

‘You hear that, Koba?’ says Shaumian. ‘Socialists and warring gangsters. A real home from home.’

They must register in the Polish Workers Club. Outside its grey door, watching the delegates arrive are an odd assortment of onlookers: bored men from the London newspapers in more or less serviceable suits and bowler hats, two men from the Okhrana in thick coats, buttoned against the drizzle, and two youngish men from MO5, hiding their own boredom behind the keen stares befitting policemen recently promoted from uniformed duties. A man from the Daily Mirror goes to the trouble of taking a picture but he has the casual style of someone who knows it won’t be used. This is just the reflexive action of a conscientious employee.

An Okhrana man spits on the ground. He has no interest in blending in. His job is not just to see but to be seen. We’re on to you, his presence says. Your studied ordinariness won’t save you, your ridiculous aliases won’t save you, we see it all, my colleagues and me, we see it all and find it pathetic, frankly. Besides, the best of you work for us.

The men stop. Koba grunts. Then he’s off, stepping towards the little gaggle of spectators in that pigeon-toed way he has.

He plants himself in front of the reporter who took the picture. In his tunic and his high boots he has a comic operetta look, an impression strengthened when he pulls himself up to his full two arshini height and flourishes an open palm before him like a messenger on the stage. Like a minor character from Chekov. The reporter, a dumpling-faced man with mild clerical eyes, simply stares back. A silence stretches out between them.

‘Koba!’ Shaumian hisses, ‘Koba! What are you doing?’

Koba says nothing but jerks his hand out further towards the blinking journalist. One of the other reporters laughs.

‘I think he wants the snap, Ralph. Maybe it’s a souvenir of his trip to England, something for the wife and kiddies.’

‘This lot don’t do family life, mate,’ says a companion. ‘All free love and nudism for them.’

‘Well, whatever he wants he can bloody whistle,’ says the man called Ralph. His face might be gentle but he has a bruiser’s voice. A voice roughened in tap-room scuffles.

Koba snaps something in Georgian. The journalists don’t speak a word of it, of course they don’t, but they understand all right.

‘You going to take that, Ralph?’ says one. ‘You going to be spoken to like that by some Russkie?’

The noises of the street seem to grow quiet. The calls of construction workers – bantering, hectoring, arguing – the creaking and squeaking of the cranes, the bells of the churches, the throb, hum and belch of the steam engines, the buskers, the street preachers, they all recede. The clamour of London reduced to the sound of heavy breaths as two men square up to each other.

Koba is never afraid to start a fight. He is used to winning them, too. As a child he ruled both the school and the streets. If he ever lost an initial struggle he would wait and attack from behind when his opponent was walking away, slamming him into the ground and driving his knee into the boy’s chest while his supporters – and there were always many supporters – cheered and clapped. The defeated boy might protest vehemently, might call him a cheat, but it didn’t matter: the young Koba would be acknowledged the victor.

These are the tactics he has continued to follow in adulthood. Do what needs to be done. Doesn’t matter whether you’re hijacking a ship, robbing a bank or fighting over a girl. Go in hard. Use the element of surprise. Give no quarter. Don’t allow yourself the luxury of mercy. The one good piece of advice his father gave him: there’s no better time to kick a man than when he’s down.

Shaumian is at Koba’s side now. He soothes the pressmen in English that is broken but warm. He apologises for his impulsive friend, explains as best he can that photographs are sometimes dangerous for them. That they are all on edge. Volatile times in their home country. A rough sea voyage too, it all takes a toll on the nerves. Plus, they are all hungover.

The journalists smile. They can sympathise with that.

‘Yes, well,’ says the man called Ralph. ‘He acts like that again and he’ll get a punch in the bone-box. This is England, chum.’

Tskhakaya meanwhile hauls Koba away. ‘You’ll get us all arrested or beaten up. Or worse. We’re here to work, not to perform amateur theatricals on the pavements.’

Koba shakes himself free. Takes a breath, holds it and then exhales noisily. For a moment it’s as if he’s going to apologise, admit that he acted hastily and in error.

‘Let’s just get inside,’ he says.

2

We Can Dream

At the registration desk, Koba, Shaumian and Tskhakaya line up behind a group of women delegates who are cheerily discussing how to make bombs from household items such as sugar and weedkiller, and how to best protect your clothes while you do it. The most talkative woman has her back to them and they marvel at how her hair is coiled into a red-gold plait that follows her spine to her waist.

‘Such an education these Congresses,’ says Shaumian, too loudly.

He tells them that a year ago at the 4th Congress in Stockholm a girl from Siberia had taught him how to dislocate the shoulders of an attacker in one simple manoeuvre. It is a story the other men have all heard several times.

‘It is something that will come in very useful one day I’m sure,’ says Tskhakaya.

The women make frank eye contact and give strong handshakes as the men introduce themselves. Not one of them is older than twenty-five and all have an athletic, self-confident manner. They are dressed in clothes that are more flowing and less restrictive than those worn by most of the women they have seen on their way across London.

‘Artistic clothes,’ whispers Shaumian. ‘It is the fashion among the young.’

The women are polite as they give their own names but they seem unimpressed by the men. Not dismissive, exactly, but cool, brisk and business-like. We are not on holiday, their manner says, we have things to accomplish. Targets, goals. We will not be distracted by anything while we’re here, least of all men.

‘Where are you from?’ says Koba to the girl with the plait, the girl who has given her name as Elli Vuokko. She sighs and in that exhalation is a rebuke, the weary sense that she has to field approaches like this all the time and if he absolutely has to talk to her, can’t he do better than this? Can’t he show a bit more imagination?

She tells him she is a delegate of the lathe operators from a place called Tampere in Finland.

‘I have been to Tampere,’ says Koba.

‘No one has been to Tampere,’ says the woman, her eyebrows arching, her eyes laughing.

‘Not only have I been there, it was where I first met Comrade Ulyanov. It was where we began to solve the problem of rebuilding the finances of the party.’

‘Ah, the famous delegate from Upper Kama,’ she says. Her voice is amused, sardonic, but her expression softens. Any friend and valued colleague of Comrade Ulyanov is obviously a friend and valued colleague of hers.

Comrade Ulyanov. The Mountain Eagle. Lenin.

Now Koba is close to her, close enough to smell the clean, floral scent of her, he can see that she is even younger than the other women, no more than nineteen. Acid blue eyes. Must cause consternation in her local party meetings.

Still, the lathe operators have voted her their delegate when they could have sent a mature man, which argues for a powerful personality as well as striking looks. In Koba’s experience, women have to fight twice as hard as men to be heard in meetings, and young women twice as hard again.

Perhaps things are different in Finland from the way they are in Georgia, but surely not that different.

Elli shrugs now, her disconcerting eyes shift away from Koba’s to fix on a point on the far wall.

She moves away. ‘See you tomorrow, brothers. Early.’

‘Yes, such an education,’ breathes Shaumian. ‘The future is arriving my friends. The future is arriving and it is wearing skirts and knows how to dislocate your shoulders. Strange and exciting times.’

The three men watch the girls swish off to their lodgings until the tired clerk at the desk coughs and sighs that he hasn’t got all day and are they signing in or not?

They are given the necessary passwords and handed their allowance and select their new codenames for the week. Koba is Mr Feodor Ivanovich. It is a name he has used before and one he likes. It sounds nondescript and respectable, but it also has a certain swing to it. It was also the name of the Emperor that came after Ivan the Terrible. That appeals to him.

Tskhakaya chooses the name Barsov – The Leopard. Can that really be how this middle-aged schoolteacher sees himself? As a savage cat, lithe and merciless?

Shaumian opts for Ayaks, after the fearless warrior of Greek mythology.

They are given the name of their lodgings: Tower House on Fieldgate Street.

‘You’re all with me, old chums,’ says a declamatory, music-hall voice overflowing with good cheer. ‘The world revolution hasn’t even reached here yet and they are sending us all to the tower anyway.’

‘Litvinov!’ Koba breaks into one of his rare grins, a white flash of blunt square teeth. He is genuinely pleased to see him. They all are. Litvinov is a big man with big appetites. Eager for love, for laughter, for the ordinary madnesses that can be turned into good stories later. A boozer, a brawler and a comedian.

Also the gunrunner for the party. A man renowned for last year’s hilarious ruse of pretending to be a procurement officer of the Ecuadoran army. This disguise had resulted in the Bolsheviks being sold weapons by the very forces they intended to use them against. He is a man full of schemes, a man who says yes to every suggestion of an adventure. One of those people others warm to, even those like Koba who are naturally suspicious of charm.

Shaumian produces a flask from an inside pocket and the men pass it around drinking deeply, making a performance of it.

‘What is it like, this Tower House?’ Shaumian asks. Litvinov has lived in London and is considered an expert on the city and its inhabitants.

Litvinov laughs now. ‘Let us be positive, my friend. Let us say only that we will not be costing the party too much money. But maybe those beautifully fierce lady delegates will be billeted there too, hey?’

‘We can dream,’ says Koba.

Litvinov laughs again, claps him on the shoulder. ‘Exactly, my friend, that is what a good revolutionary does – first he dreams the world and then he makes that world. That’s what makes us like gods.’

The female delegates are not billeted in the same place as the three Georgians and Litvinov. Stupid to hope to be lucky like that. In any case it is good that the party is not so unchivalrous that it sends its women to Tower House. The lodging house is in a dangerous neighbourhood after all, where the streets are among the worst in London, where most of the houses are in need of repair, with many divided into two-roomed apartments or, like Tower House, turned into cheap lodgings.

The men fall silent and grow watchful as they approach. Even in daylight these streets are gloomy, with toughs in thin jackets standing idle in doorways. Respectable women would be nervous walking to and from here every day. Even those who can dislocate shoulders.

At Tower House they find the doors open onto a canvas screen displaying a notice that a bed costs sixpence a night. In the hallway is a group of blank-faced youths. Nodding at these ill-dressed young men as they pass through the outer door, they find themselves opposite a little window in a recess. Here the manager sits to collect the money for the night’s lodging, and keeps the limited range of foodstuffs he sells to the lodgers. Bread. Butterine. Canned fish. Beans. Oatmeal. Potatoes. Gin.

The manager is a wheezy man, with a broad chest and a large grey face. He summons a boy of no more than ten who he introduces as Stan, head cook and bottle-washer.

‘Whatever you need, Stan is your man,’ he says. ‘And I mean absolutely whatever you need, gents. If Stan can’t get it for you then it’s not worth having. I call him my little fixer.’ He winks unpleasantly. Coughs.

Stan says nothing. He simply sniffs and rubs at his nose with the back of a grubby hand. He is a thin boy but tough-looking. Wiry. Sharp-eyed. Snub-nosed. He is dirty and wearing cheap clothes that are too big for him, cuffs turned back on his jacket, the ends of his trouser legs haphazardly turned up, but somehow carrying himself with the dignity of a serious middle-aged man, as if he is an usher in a court or an assistant funeral director.

Following Stan through the second door, they enter a moderate-sized low kitchen, where about twenty men and women are sitting on long wooden benches, or standing round the fire. Half of them are smoking pipes or cheap cigarettes and most of those who aren’t are chewing tobacco instead. The air is thick with smoke and the floor slimy with brown expectorant.

Litvinov tries to cheer his companions. He rubs his hands together.

‘This isn’t so bad,’ he says. ‘Warm places to sit and think.’ He gestures at the plain deal tables and benches around the room.

‘Not warm,’ says Shaumian. ‘Stifling.’

He is not wrong, and the clammy fug is not helped by the fact that all the windows are closed. The smell is even worse in here than in the streets. It is obvious that most of those in the room rarely change their clothes.

‘Come on, man,’ says Litvinov. ‘Let us not be downhearted. Gloom is a contagious disease you know. It’s our duty to fight it, to keep ourselves free of it. And, look, there will be lots of tea at least.’ It is true, on the chimney-piece are several tin teapots.

‘Yes, but English tea,’ says Koba. He makes a face.

‘No pleasing some people,’ says Litvinov, smiling. Sometimes it seems everything Koba says, however sour, makes Litvinov smile. He finds him endlessly amusing.

Following the spirit of the conversation if not the words, Stan opens a cupboard to reveal the plain plates and cups and saucers which he says are for the free use of the lodgers. He explains that in the basement under their feet is the washing-place and coke cellar, and that on the first floor over the kitchen and a little back room where the manager sleeps, are the beds for couples, and above that a large dormitory for single men. That’s where they will be sleeping.

They follow Stan’s skinny form as he walks gravely up the stairs and so pass the room where the couples sleep. It costs an extra penny a night to get one of the double beds. It is Shaumian who points out that the privacy of these leaves a lot to be desired. Each couple is divided off by boarding about seven feet high, leaving a considerable space between the top of the partition and the ceiling.

‘I am sure the women like it this way,’ Tskhakaya says. ‘It means they are never quite alone with any of the brutes they are sleeping with. Rescue is always possible even if privacy isn’t.’

‘The women that end up here are the ones who really need to be able to cripple men,’ says Shaumian. ‘They are the ones that should learn how to dislocate shoulders. Our female comrades should run classes for their English sisters while they are here.’

There are sixteen beds in the male dormitory, though only two are occupied and neither occupant so much as glances at them as they come in. Hostels, like jails, are the same the world over – curiosity is a dangerous vice in these places. If you want to stay safe you keep yourself to yourself.

These men look like natural victims, look like people who should always make themselves as invisible as possible. Mind you, they also look like they have nothing you’d want to steal. They are just two evil-smelling bundles of rags and bones, two more streaks of pale piss on damp and reeking mattresses.

‘I hope our women are in better places than this,’ says Shaumian.

‘You think about women too much,’ says Koba.

‘So speaks the recently married man.’ Litvinov smiles.

The young women of the Congress are not anywhere like this. They are scattered across London in establishments that vary in quality, but none are in accommodation as rough as Tower House.

At the same moment as the Georgians are surveying their sad lodgings and wondering if they can stand ten days in that place, the representative of the lathe operators of Tampere, Elli Vuokko, is laughing as she plays a noisily competitive card game with Nina Kropin, the delegate of the Kostroma textile workers. They are in Langton House, the bright, clean YWCA in Upper Charlotte Street. The building is new, designed by the eminent architect Beresford Pite in his individual Arts and Crafts manner with banded brickwork. It is named after an unfortunate former Archbishop of Canterbury, Bishop Langton, who died of the plague after only five days in office but was famous for his endowments helping young people develop their natural gifts. No doubt he’d be gratified to know that this monument to his life is modestly comfortable with every little cubicle and bedroom having its own window and electric light – there is a washroom that smells of lemon, and a workroom containing provision for heating irons for the use of the ninety female boarders.

The drawing room is mainly for reading and music, something that would also have delighted the good Bishop.

Comrade Litvinov is right that gloom is a contagious disease, but he should remember joy is catching too. Fuelled by a rich mutton stew, Elli Vuokko and her new friend are infecting each other with a love of life. They are giddy with the excitement of being young in London, of being part of a movement that will change the world for the better. They catch each other smiling, they laugh at odd moments.

Elli Vuokko shows Nina the umbrella her workmates bought her to ward off the inevitable London showers. In return, Nina shows Elli the revolver she brought over on the ferry.

‘Enough wallop to kill an elephant, small enough to fit in your purse.’

Elli’s eyes widen. ‘You carry this around?’

Nina laughs. It’s not like Russia, she tells her. They check nothing here. Think about it: they didn’t even need passports to get into the country. Elli feels the weight of the weapon in her hand. The balance and heft. She holds the gun up to the light. Admires the sleek, clean, thoroughly modern look of it.

‘Suits you girl,’ says Nina.

‘Surprisingly comfortable. Snug.’

‘I’ll tell you what it feels like,’ says Nina with a grin. ‘It feels like when you hold a man’s ball sack in the palm of your hand.’

‘I’ll take your word for it.’

They both laugh. Everything the other says is droll or clever or wonderfully ridiculous and these high spirits attract looks from other guests. Some, those trying to read improving novels for example, are censorious but most can’t help smiling. Good to hear young women laughing.

Neither Elli nor Nina give the men of the Congress any thought at all.

Langton House also features a shop and a restaurant which provides meals for women that are fresh, filling, nourishing and cheap. There is no restaurant in Tower House so Koba and Litvinov leave Shaumian and Tskhakaya guarding their luggage to wander out into the teeming and broken streets to get something to eat.

They find themselves in a chop house, sitting at a bare wooden table on one of four high-backed pews in a low and poorly ventilated room. It smells of cigarette smoke of course, but also of cheap fat and over-cooked vegetables.

‘This place reeks like a bloody hospital,’ says Litvinov. ‘It’s probably as dangerous as one too.’

‘It’ll do,’ says Koba and after a few moments, surrounded by merrily boisterous working men, they are prodding at the soggy crusts of steak puddings.

While they eat they talk of the old familiar topics: who should do what in the coming civil wars and the party’s constant need for money if those wars are to be won.

‘You know, they want to put a final stop to the expropriations?’ says Litvinov.

‘That again. And who are They this time?’

‘Same crowd. The bundists of course. And Martov and his cronies obviously.’

‘Obviously. Do we care about them?’

‘We probably should. Martov especially has a great deal of influence now. He is in the ascendant definitely.’

‘And without the money we bring how will the party survive? You can’t organise a revolution on the cheap.’

‘No need to argue with me, brother. I’m on your side. I guess they think something will turn up.’

‘People born rich always think something will turn up because for them something always has. They forget about the need for constant work. They get blasé about planning, about organisation, about the need to be always vigilant, always striving for opportunity.’

Litvinov nods. It is true, brother, but what can you do?

The conversation moves from ideas to personalities and from there it slides into gossip, who said what to whom and how much they can be relied upon.

They eat quickly and less than half an hour after receiving their meals Litvinov suggests they return to Tower House. Koba demurs. ‘You go ahead, my friend. I will sit here and drink another coffee – which is horrible but better than the tea – and record my impressions of England in a letter to my wife.’

‘Ah, yes, the lovely Kato. You must miss her – and little Yakov too, of course. How old is he now?’

‘Just three months.’

‘Three months! I don’t know how you can bear to be away from them and here in this place instead.’ Litvinov flaps his hand in a way that takes in the dirty tables, the fat and fearless flies and the walls unadorned save for a couple of playbills proclaiming the wonders of a nearby music hall.

‘I simply do what has to be done. I simply go where I have to go when I have to go there.’

Koba’s voice is cold and his dark eyes have a hard gleam. It is remarkable how quickly Koba can give in to anger, how it can come over him at any time. Litvinov feels sorry for him. It must be an exhausting way to live. It can certainly be tiring to be around. He smiles, claps Koba on the shoulder and asks him to send Kato his love.

After Litvinov has gone, Koba closes his eyes for a moment, suddenly weary. He takes a breath, a swallow of weak and lukewarm coffee and, with a sigh, forces himself to work on his letter for twenty minutes.

Dearest Kato, this city is a machine . . . grinds . . . crushes . . . people here milled and turned until they are less than human . . . The words don’t come easily and they don’t ring true in any case. He tries again: Dearest Kato, how is Yakov, does he smile yet? Is he becoming his own little person . . .

It’s no good. He rises, leaving a small pile of change on the counter. That has to be enough.

He has only moved a few paces from the eating house when a couple step out of the grey smudge of evening shadow. A man and a woman who are neither old nor young, neither smart nor shabby. You can’t assess their class very easily. She is perhaps a Lady Correspondent for one of the popular newspapers, or maybe she is the authoress of romance novels, with a small but devoted following among the users of circulating libraries. She has the air of someone whose mind is on other things, that she isn’t quite here.

Maybe he is a theatrical agent, with a harem of actresses hoping he’ll get them on the serious stages. There is a hint of something Bohemian about them. Something not quite English in the way they walk and the way they wear their clothes and hair. Something European. Some flamboyance.

Perhaps it is just that their clothes are clean.

This suspicion that they aren’t English is confirmed when the man addresses Koba in precise educated Russian.

‘Excuse me, Sir, we are looking for places to eat while staying in London and wondered if you’d recommend the establishment you have just left?’

Koba has been expecting something like this. Here it comes, he thinks. Orders, instructions, forceful reminders of who is in charge.

‘We have had nothing but bad luck with our choices of restaurant,’ says the lady. Her voice is soft but clear enough and her Russian is accented. Estonian he thinks. Or Lett. A hint of cold Baltic seas anyway.

‘But we couldn’t help noticing that you left a substantial gratuity which suggested that this was a most satisfactory place.’ Koba knows the stranger is mocking him somehow though his face maintains a blandly pleasant expression.

‘It’s all right I suppose,’ says Koba. ‘Though there are nicer places.’ He has coarsened his own Russian, made his accent brusque and rough.

‘Oh?’ says the lady. ‘Where for instance?’

‘Kettner’s in Rommilly Street, for instance. The Pall Mall Gazette rates it highly.’

If the Okhrana want to boss him about then they are going to pay properly for the privilege. His time and conversation are worth more than the price of a meal in a filthy pie-shop.

The lady turns to her companion. ‘Shall we eat there tomorrow then? At about 9pm? After most other diners have gone home and we can hear ourselves think?’