5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Bradecote & Catchpoll

- Sprache: Englisch

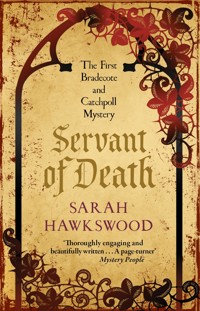

The first Bradecote & Catchpoll medieaval mystery June, 1143. The much-feared and hated Eudo - the Lord Bishop of Winchester's clerk - is bludgeoned to death in Pershore Abbey and laid before the altar like a penitent. A despicable man he may have been, but who had reason to kill him? As the walls of the Abbey close in on the suspects, Serjeant Catchpoll and his new, unwanted superior, Undersheriff Hugh Bradecote must find the answer before the killer strikes again ... PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED AS THE LORD BISHOP'S CLERK

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Servant of Death

A Bradecote and Catchpoll Mystery

SARAH HAWKSWOOD

For H. J. B.

Contents

The First Day

June 1143

Chapter One

Elias of St Edmondsbury, master mason, stood with the heat of the midsummer sun on broad back and thinning pate, rivulets of sweat trickling down between his shoulder blades. The wooden scaffolding clasped the north transept of the abbey church, close as ivy. Where he stood, at the top, there was no shade from the glare when the noontide sun was so high, and today there was little hint of a breeze. The fresh-cut stonework reflected the light back at him, and his eyes narrowed against the brightness. He turned away, blinking, and then looked down to the eastern end of the abbey foregate, where the usual bustle of the little market town of Pershore was subdued. It was too hot for the children to play chase; many had already sought the cool of the river and its banks, although even the Avon flowed sluggishly, too heat-weary to rush. As many of their seniors as could afford to do so were resting indoors. The midsummer days were long, and the townsmen could conduct their trade well into the cooler evening, though the rhythmic ‘clink, clink’ from the smithy showed that some labour continued. The smith was used to infernal temperatures, thought Master Elias, and probably had not noticed the stultifying heat as he laboured at his craft.

One industrious woman was struggling with a heavy basket of washing she had brought up from the drying grounds to the rear of the burgage plots. She halted to ease her back and brush flies away from her face, then stooped to pick up her load once more. As she straightened she had to step back smartly to avoid being run into by a horseman who rounded the corner at a brisk trot, raising unwelcome earthy red dust as he did so. The man, who rode a showy chestnut, was followed by two retainers. The woman shouted shrill imprecations after the party as they passed from Master Elias’s view, turning along the northern wall before entering Pershore Abbey’s enclave, but he would vouch that they ignored her as they had her now dusty washing.

The scaffolding afforded a grand view of the comings and goings at Pershore, though Master Elias would have taken his hand to any of his men whom he saw gawping in idleness. As master mason, however, he could take the time to survey the scene if he wished. He never failed to be amazed at how much could be learnt of the world from the height of a jackdaw’s roost, and he had an eye for detail, which was one of the reasons his skills were so valued. As the sun rose, heralding this hot day, and he had taken his first breath of morning air from his vantage point, he had watched as a troop of well-disciplined horsemen passed through the town, led by a thickset man who rode as if he owned the shire. Master Elias would have been prepared to bet that he did indeed own a good portion of it. Few lords had men with guidons, though he did not recognise the banner. They were also heavily armed, not just men in transit, and they rode with menacing purpose. The latest arrival, in contrast, was a young man in a hurry, for his horse was sweated up and he had not bothered to ease his pace in the heat of the day. His clothing, which proclaimed his lordly status, was dusty, and Elias did not relish the duties of his servants who would have to see to hot horses and grimy raiment before they could so much as contemplate slaking their own thirst.

The nobleman who had arrived earlier in the day had been much more relaxed. He had more men but had ridden in on a loose rein, one arm resting casually on his pommel. Everything about him had proclaimed a man who knew his own worth and had nothing to prove. Something about him was vaguely familiar to Elias, and the thought that he had seen him before was still niggling at his brain. It was a cause of some irritation, like a stone in a shoe. Elias liked everything in order, from his workmen’s tools to his own mind. A question from one of his men dragged both thoughts and eyes away from the world below, and he turned back to the task in hand with a sigh.

Miles FitzHugh dismounted before the guest hall, head held proud. He rather ostentatiously removed his gauntlets and beat them against his leg to loosen the dust, but then ruined the effect by sneezing. Once the convulsion had passed, he issued terse commands to his long-suffering grooms, who led the horses away to the stables. The young man permitted himself a small smile, enjoying the chance to command others. In his home shire, and away from the entourage of the powerful Earl of Leicester, where he was only one of the young men serving as squires, he could flaunt his own noble birth and status. He had not the insight to realise that this pool, in which he saw himself as the biggest fish, was nothing greater than a stagnant puddle. He entered the cool gloom of the guest hall, his eyes unaccustomed to the low light, and collided with a tall, dark man who made no attempt to step aside. FitzHugh was about to make his feelings known, but his eyes had now made their adjustment, and before the hard glare and raised brows at which he had to look up, remonstration withered on his lips.

‘You should be less hasty, my friend.’ The voice was languid, almost bored, but the word ‘friend’ held a peculiar menace to it.

Taking stock of the man’s clothing, Miles FitzHugh made a rapid alteration to his own manner. ‘My apologies, my lord.’ His voice was refined and precise, but with the deferential tone of one long used to service, and one also used to thinking up excuses swiftly. ‘My eyes have been dazzled by the sun.’

‘Then all the more reason to proceed with caution.’

The tall man was at least a dozen years FitzHugh’s senior, and, by dress and bearing, far superior in rank to a squire, even one in the household of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester. FitzHugh mumbled an apology and drew aside, almost pressing himself into the hard, cold stone of the whitewashed wall. The older man inclined his head and gave a tight smile as he passed out into the sunlight. The squire would have been galled to have seen how much broader the smile grew once he was in the open.

‘Jesu, was I ever that callow?’ muttered Waleran de Grismont as he crossed the courtyard. His eyes were roving, sharp as a raven’s, taking in everything going on around him. The usual routines within an abbey’s walls were being carried out, as if the monastic world worked on a different level to the secular, aware of its existence but uninterested in its activities. The master of the children was leading his youngest charges to the precentor for singing practice. They followed him with eyes lowered, giving the casual observer the appearance of humility and obedience. De Grismont was amused to see that two lads towards the rear were elbowing each other surreptitiously, and another was picking up small stones and flicking them at a large, pudding-faced boy waddling along in front of him. The perpetrator sensed an adult gaze upon him, and he cast a swift glance in the direction of the tall, well-dressed lord. His eyes met those of de Grismont for an instant, and he grinned, correctly judging that the man would appreciate boldness. The nobleman gave an almost imperceptible nod, and the boy relaxed. The lord clearly remembered the misdeeds of his own youth.

In the shade of the infirmary, a woman was in conversation with the guestmaster. She had an air of competence and efficiency, and seemed perfectly at ease. She was dressed without ostentation, but the cloth of her gown was of fine quality. Her garb, thought de Grismont, was finer than her lineage. Her hands had seen work, and her face and figure were comely but lacking in delicacy. A few years hence and she would be commonplace and plump. He was a man who assessed women frequently and quickly, and he prided himself on his judgement. She held no further interest for him, and he turned the corner to the stables. Had anyone seen him within, they would have found that he looked not to his own fine animal, but to a neat dappled grey palfrey, a lady’s mount. He patted the animal as one who knew it well, and smiled.

Mistress Margery Weaver knew the guestmaster from previous visits to the abbey, and each understood the manner of the other. In the comparative cool where the infirmary cast its short noontide shadow, she was arranging for payment for her lodging and that of her menservants, who acted as her security when she travelled far from home. In addition, she would leave money for Masses to be said for the soul of her husband. In some ways, she acknowledged to herself, this was a sop to her conscience, because although she had been a loyal and loving wife she was enjoying her widowhood. Her husband had been a man of authority within the weavers’ guild in Winchester, but had died of the flux some three years past. Their son was then only seven years old and so it was Margery who took up the reins of the business, as was accepted by the guild. She came from a weaving family, and had no difficulty in assuming her late husband’s role. What she lacked in bluff forcefulness she made up for in feminine ingenuity, and she had seen the business flourish. She had a natural aptitude for business, and she found it far more interesting than the homely duties of being a wife.

Each summer she headed west to the Welsh Marches, which was where Edric had gone for the best fleeces. She did as he had done, and the journey provided her with a welcome change of scene, almost a holiday. Both on the outward and return trips she broke her journey at Pershore, and the guestmaster regarded her visits as much a summer regularity as the arrival of the house martins in the eaves.

A habited figure emerged from the abbot’s lodging and acknowledged her presence with a nod and the hint of a sly smile. She lifted her head and pointedly refused to return the gesture. The guestmaster was somewhat surprised, for Mistress Weaver was not a woman of aloof manner. He was also taken aback that the monk, who had no cause to acknowledge the woman’s presence, had looked upon her. It was not, he thought, seemly that a Benedictine should do so, but the man was not a brother of Pershore, and there was no suitable place for him to raise the error. He would certainly not mention it at Chapter.

Margery Weaver’s cheeks flew two patches of angry red colour and her bosom heaved in outrage. Her lips moved, and it was not in prayer. The guestmaster averted his own gaze for a moment, and compressed his lips. Women were definitely a wicked distraction. He wondered why she had reacted in such a way, but wisely refrained from asking for explanation.

Brother Eudo, clerk and emissary of Henri de Blois, Bishop of Winchester, permitted himself a silent laugh as he turned away. Mistress Weaver’s refusal to acknowledge him did not distress him. In fact, her annoyance gave him a degree of pleasure completely at odds with his religious vocation. He was a man who gained untold delight in the discomfiture of others, almost as other men took it from the pleasures of the flesh. It was not an aspect of his character which endeared him to his fellows, and even the bishop had found it difficult to turn a blind episcopal eye to the fault, but Eudo was too useful, and the eye was therefore turned.

Way above the town, high on Bredon Hill, William de Beauchamp, sheriff of the shire, was making his dispositions as the day heated up. He had led his men into the southern part of his shrievalty, to the hill of Bredon, for the purpose of dealing with a lawless band that had been troubling the king’s highway between Evesham and Pershore, and even southwards towards Tewkesbury. In a violent time when minor infringements were sometimes overlooked, their depredations on the merchants and pilgrims upon this route had become so heavy as to make the sheriff take action, if only to silence the vociferous complaints of the abbots of Evesham and Pershore, and even Tewkesbury, although the latter lived under the Sheriff of Gloucester’s aegis. That de Beauchamp supported the Empress Maud, and not King Stephen, made no difference to the need to maintain the rule of law, the King’s Peace. The office of sheriff was lucrative, since he was permitted to ‘farm’ some of the money he gathered in taxes for the king, and it made a man a power to be reckoned with within the shire. The day-to-day administration of justice he generally left to his serjeant and to his undersheriff, but this band had been big enough to cause him to lead retribution himself. Besides which, if they were upon the hill they were far too close to his own seat at Elmley, and he had no intention of being embarrassed by being told his own lands and tenants had suffered. In addition, his undersheriff, Fulk de Crespignac, had taken to his bed, sick.

His serjeant, old Catchpoll, was a sniffer of criminals, a man who could track and out-think the most cunning of law breakers by the simple expedient of understanding the way that they thought but being better at it. De Beauchamp had sent him to scout ahead, and he had returned with the news that the camp they sought was empty but not abandoned.

‘They’ve gone a-hunting like a pack of wolves, my lord, and I’d vouch they’ll be back as soon as they’ve brought down their prey. The camp was used last night. Their midden is fresh and there was fires still warm with ash.’ Catchpoll mopped a sweat-beaded brow.

‘Might they not move to another camp tonight?’ said the lord Bradecote, a tall man, sweating in good mail and mounted on a fine steel-grey horse.

Catchpoll turned to him with a derisive sneer.

‘They’re coming back, my lord. They tethered a dog. Now they would not do that if they were on the move proper, but they might if the animal was like to ruin a good ambush.’

Hugh Bradecote nodded acceptance of this theory.

De Beauchamp sniffed. ‘Then we ambush the ambushers upon their return. Which way did they go, Catchpoll?’

‘Down onto the Tewkesbury road, about a dozen ponies, though from the hoof prints, even in this dust and dryness, I’d say as some beasts carried two, or else the living is far too good and we should take to thievery, for it would mean very heavy men in the band. Say up to twenty, all told.’

‘If they intend to return then we want to push them. Bradecote, take your men and follow Catchpoll to the camp. He can show you where to lie concealed.’

‘I think I can make my own judgement upon that, my lord.’ The subordinate officer had his pride, and being treated like a wet-behind-the-ears lordling by the grizzled Serjeant Catchpoll did not appeal.

‘As you wish, but if any escape this net, I’ll be amercing you for every man. I shall take my men down a little off their track and await them starting back up the hill. We will drive them like beaters with game, on to your swords. They may be greater in number, but mailed men with lances are rarely matched by scoundrels with clubs, knives and swords they have stolen. They’ll run for camp to make a stand where they know every bush. Be behind those bushes.’

The sheriff pulled his horse’s head round and set spur to flank. ‘Oh, and don’t kill the lot. I want men to hang. Makes a good spectacle and folk remember it more than just seeing a foul-smelling corpse dragged in for display, and in this weather they will go off faster than offal at noon.’

A lull fell upon the abbey after Sext. Monks and guests alike ate dinner, and if the religious were meant to return to their allotted tasks, there were yet a few heads nodding over their copying in the heat. The obedientaries of the abbey could not afford to be seen as lax, and went very obviously about their business, but mopped their brows covertly with their sleeves if they had cause to be out in the glare. Two or three of the most elderly brothers could be heard snoring softly, like baritone bees, in favoured quiet and shady corners, but their advanced age gave them immunity from censure. Many of the wealthier guests kept to the cool of their chambers, for they did not have to share the common dormitory, but a well-favoured and well-dressed lady promenaded decorously within the shade of the cloister, thereby raising the temperature of several lay brothers, already hot as they scythed the grass of the cloister garth. When their job was complete they were hurried away as lambs from a wolf by the prior, who cast the lady a look of displeasure. She smiled blithely back at him, but in her eyes lurked a twinkle of understanding, and when he had turned away her lips twitched in unholy amusement. Men, she thought, were all alike, regardless of their calling. The only difference with the tonsured was that they tried to blame women for attracting them. It was not, she thought mischievously, her fault if she could draw a man’s gaze without even trying; her looks were natural, a gift from God, and it was only right to use them.

Isabelle d’Achelie was in her late twenties, with the maturity and poise to be expected of a woman with the better part of fifteen years of marriage behind her, but with the figure and complexion of a girl ten years her junior. It was a fascinating combination, and she knew just how to utilise it.

As a girl she had dreamt of marriage to a bold, brave and dashing lord, but reality had brought her the depressingly mundane Hamo d’Achelie. He was a man of wealth and power within the shire, a very good match for a maid whose family ranked among the lower echelons of landowners. Her father had been delighted, especially as he had three other daughters. None were as promising as his eldest, but one outstanding marriage would raise him in the estimation of his neighbours. Isabelle was a dutiful girl who knew that she had no real say in whom she wed, and besides, she was fond of her father. He would not have countenanced the match if d’Achelie had a bad reputation as man or seigneur. Hamo d’Achelie was in fact a decent overlord and pious man. He was, however, nigh on forty-five years old, had buried two wives over the years, and exhibited no attributes that could inspire a girl not yet fifteen. Isabelle had done as she was expected, but wept at her mother’s knee.

Her mother had given her sound advice. A husband of Hamo’s years and apparent disposition, which was not tyrannical, would be likely to be an indulgent husband. She would be able to dress well, eat well and live in comfort. The duties of a wife might not be as pleasant, but, if she was fortunate, her lord’s demands upon her should not be excessive.

So it had proved. Hamo had never sired children, within or outside of marriage, and had, somewhat unusually, accepted that this was not the fault of the women with whom he lay. It was a burden laid upon him from God, and he had learnt to live with it. His third marriage sprang, therefore, not from desperation for an heir but from his infatuation with a beautiful face. He adored his bride, and denied her nothing. Isabelle found that marriage was comfortable but unexciting. Her husband treated her as he would some precious object, and took delight in showing her off to his friends and neighbours. He decked her in fine clothes and watched his guests gaze at his wife in undisguised admiration. His pleasure lay in knowing how much they envied him.

Isabelle had learnt the rules of the game early on, and played it with skill for many years. She was a loyal wife, and would never be seen alone with another man, but when entertaining she had learnt how to flirt with men while remaining tantalisingly out of reach. She had become highly adept, and it both amused her and gave her a feeling of superiority over the opposite sex that she had never expected. What she lacked was passion; but then Waleran de Grismont had entered her life. Just thinking about him made her blood race as nothing else ever had.

De Grismont’s lands lay chiefly around Defford, but he had inherited a manor adjacent to the caput of Hamo d’Achelie’s honour some four years previously. His first visit had been one of courtesy, but he had found the lady d’Achelie fascinating, and had found excuses to visit his outlying manor more and more frequently. He had become good friends with Hamo, and never overstepped the line with Isabelle in word or deed, but she had seen the way he looked at her when her husband was not attending. She was used to admiration, but not blatant desire, and it oozed from every pore of the man. Three years since, Hamo had been struck down by a seizure, which left him without the use of one side of his body. He had been pathetically touched by her devotion and attention to the wreck he knew himself to be, and openly discussed his wife’s future with his friend. She was deserving, he said, of a husband who could love and treasure her as he had become unable to do.

What neither Hamo nor his beautiful wife realised was that Waleran de Grismont liked things on his own terms, and was conscious of feeling his hand forced. He had resolved to distance himself from the d’Achelies for a while, and sought sanctuary in the ranks of King Stephen’s army. He was not, in truth, very particular whose claim was most just, but since Stephen was the crowned king, it seemed a greater risk to ally oneself to the cause of an imperious and unforgiving woman, which the Empress Maud was known to be. The king’s army was heading north to ward off the threat of the disaffected Ranulf, Earl of Chester, and it was not long after that de Grismont found himself fighting for his life in the battle of Lincoln. He was no coward, and fought hard, but, like his king, was captured, and held pending ransom.

In Worcestershire, as months passed, Isabelle d’Achelie had shed tears of grief and frustration, and even contemplated asking her ailing husband if there were any way of assisting in the raising of the required sum. Thankfully, such a desperate measure proved unnecessary, as she received news of de Grismont’s release. He sent a message, full of soft words and aspirations, but did not return to see her. She had been hurt, then worried. Had he cooled towards her, found another? When next she had news, he was among those besieging the empress at Oxford. Only when Hamo d’Achelie was shrouded for burial did he come to her again.

Absence had certainly made the heart grow fonder, at least as far as the lady was concerned. Waleran looked thinner, and, thankfully, hungrier for her. His feral quality stirred her. For his own part, he was relieved to find that his absence had achieved its aim, for there had been low times when he had regretted his abandonment of the hunt. Now all that was necessary was to obtain the king’s permission to wed the wealthy widow. It should not prove difficult to obtain, for had he not suffered imprisonment and financial hardship for Stephen, who, having been shackled in a cell in Bristow, well knew how harsh such confinement could be.

Isabelle was less sanguine. She had heard how variable the king’s moods could be. He had allowed the defeated garrison of one town to march out under arms, and then proceeded to hang the defenders of another from their own battlements. He was known, however, to have a gallant and impressionable streak when it came to women. The fair widow believed she would have no difficulty in persuading her sovereign to permit her wedding de Grismont, and had set out for that purpose, delighted at having her future in her own hands for the first time in her existence.

She was surprised when Waleran de Grismont fell into step beside her. Her pulse raced, but a furrow of annoyance appeared briefly between her finely arched brows. She did not look at him, and spoke softly.

‘I do not suppose you are here by chance, my lord.’

There was an edge to the tone, which he noted. He smiled. ‘But how could I keep away, when I knew you to be so close, my sweet?’

The lady sniffed, unimpressed. ‘It would have been better if you had mastered that desire.’

The smile broadened and his voice dropped. ‘But, you see, you are so very … desirable, and I dream of “mastering” you.’

She shot him a sideways glance through long, lowered lashes. The wolfish smile excited her. Flirting with de Grismont still had an element of danger to it that was quite irresistible after Hamo’s uninspiring veneration. Deep within there was a warning voice that urged caution. As a suitor he was bewitching, but as a husband? Would … could … such a man be bothered to even appear faithful once the prize was won? The voice of caution thought not, but in his presence caution could be ignored.

‘Besides, in times like these it is not wise for a lady to travel unescorted.’

‘You have not noticed the four horses in the stables, then, my lord, nor the d’Achelie men-at-arms?’

‘Men-at-arms should be led.’ His eyes glittered, both amused and irritated. ‘Could you trust them else to stand firm in an emergency?’

‘Would they risk their lives for me?’ She turned to him with an arch look and knowing smile. ‘Oh yes,’ she purred. ‘I rather think they would, my lord. Men so often “stand firm” for me.’ Her eyes stared boldly; she need have no pretence of maidenly ignorance.

It occurred to de Grismont that his lady love was acquiring a dangerously independent turn of mind. That was something he would have to curb once they were wed.

‘But without a leader their … self-sacrifice … might well prove in vain.’

‘Nevertheless, I need no escort to the king, unless you fear that some other man should distract me from my purpose.’

There was a brittle edge to her voice, and de Grismont sought to smooth her ruffled feathers with flattering words. As they turned the corner of the cloisters by the monks’ door into the church, he cast a swift glance around. Nobody was watching. He grasped her gently at the elbow, and, as the pair of them passed the chapter house door, he lifted the latch with a heavy click and whisked them both into the cool light within. As he had expected, there was nobody there, and there was room in one of the shallow embrasures, where an obedientary sat during Chapter, for a man to hold a woman on his knee and whisper things which would have made the usual occupant blench and then blush.

He had hoped to distract her, and for a while was most successful, but her mind was tenacious, and eventually she returned to the point of their conversation, though a little breathlessly.

‘This is all very well, Waleran, but you should, truly, not have come here. Your escort to the king may sound a good idea but might be harmful to our cause. King Stephen always likes to think ideas his own, and dislikes having his hand forced.’ She grasped her suitor’s hand and imprisoned it between her own. ‘No. Stop that. You must attend to me. Return to your estates and let me do this alone. Be patient, my love, and all will be well.’

De Grismont’s opinion of leaving such an important mission in the hands, however pretty they might be, of a woman, was not likely to please her. He chose therefore, the route of blandishment.

‘You ask patience, sweet. How can I be patient any longer? How could I remain at Defford, knowing you were so close?’ His voice was husky, and his lips close to her ear. ‘You ask too much of me, Isabelle. We have waited, and the waiting is so nearly over.’ His arm round her tightened, possessively.

‘All the more reason to take care now.’

‘You do not cool towards me, lady?’ He did not fear her reply.

‘I would not be here like this if I was, nor would my heart beat so fast.’ She laid his hand over her breast once more, and sighed.

Waleran de Grismont laughed very softly. He was sure of her now. There was much to be said for a beautiful bride, with a passionate nature that had lain dormant all too long, and a dowry ample enough even for his expenses. As long as King Stephen did not refuse her request all would be well, as she said. He thought she had a point about the king, but a small niggling doubt remained, for Stephen did not always act as sense would dictate. But even if the worst happened, and Stephen refused the match, he had woken the sensuous side of her. He was confident that he could ‘persuade’ Isabelle d’Achelie to seek the ultimate solace for the disappointment in his arms, in his bed, and then, albeit reluctantly, he would seek a rich wife elsewhere.

Voices sounded outside the door, and he felt Isabelle tense within his hold. He laid a finger to her full lips, and sat very still, listening. He could hear and feel her breathing, which was a distraction, and he had to force himself to concentrate on what lay beyond the door. He judged that two men were in conversation, and though it was whispered and he could not make out words, it was heated. Once he heard a sharp intake of breath and muffled exclamation, followed by what he would have sworn was a chuckle. After some moments they passed on, and, after a short but pleasant interlude, de Grismont led his lady to the door. He opened it a fraction, listened, and then pushed her gently but firmly into the cloister. A short while later he sauntered out, much to the surprise of a soft-footed novice.

‘Fine carvings you have in your chapter house, Brother,’ exclaimed de Grismont cheerily, and strode off. The novice was left blinking in stupefaction.

Chapter Two

Brother Remigius was fairly new to Pershore, and was still finding his feet as sub-prior. His predecessor, a promotion from within the abbey, had succumbed to an inflammation of the lungs within only a few months of his appointment, and Pershore was not such a large house that it could provide a replacement with suitable experience. Henri de Blois, while still papal legate, had heard of the vacancy and offered the services of a brother from Winchester whom he considered worthy of advancement. Brother Remigius had leapt at the chance. In such a large house as Winchester, he was well aware that his modest talents were not so outstanding as to bring him to prominence, but in a smaller community he hoped to flourish. He was not a man of huge ambition, but the move suited him very well. It certainly cost him no pang to leave the abbey where he had spent over twenty years. The atmosphere, at least for him, had soured, and he was glad to shake the Hampshire dust from his sandals.

The brethren of Pershore had received him with open minds if not open arms, and after nearly two years he was truly beginning to feel at ease. He was engaged in serious but convivial conversation with the sacrist and cellarer, on their way to a regular meeting with Master Elias to assess the progress of the repair works. Lightning, so often the bane of Pershore, had damaged the north transept in the spring storms, though fortunately upon this occasion the ensuing heavy rain had kept the fire from spreading along the roof, and the damage was limited to a fissure and badly damaged masonry on the north and east faces. Brother Remigius took no notice of the cowled figure who walked past, head bowed, and could not see that the demeanour merely hid the veiled eyes and malicious smile of the Bishop of Winchester’s clerk. The three obedientaries passed out of sight as they rounded the west end of the church and made for the masons’ workshop, a wooden structure put up against the west side of the north transept, where they were close to their work above and had access to the inside of the church via the little wooden door set into the transept wall.

Master Elias saw the black-garbed trio from above, and descended with surprising nimbleness from the wooden scaffolding to meet them. He exhibited the affable but deferential air of a hostel keeper. He might not hold them in high esteem, but he had learnt long ago how precious of their dignity minor officials could be. He also knew that he could provide answers to any question they might choose to put to him, even if he had to resort to baffling them with technicalities. He almost herded them into the welcome patch of coolness afforded by the north wall of the nave, for he doubted they had come to look at the work itself.

The sacrist was keen to know whether any additional, and thus, in his eyes, unnecessary, expenditure was foreseen. He pursed his lips and looked grave when the master mason explained that the stone had come at a premium.

‘It is no fault of mine, Brother, that your church is built of a stone now in high demand. Abbot Reginald of Evesham has, as I am sure you have heard, commissioned a new wall for the enclave there. Indeed, it is because of the use of local masons upon it that I come this far west. This,’ Elias patted the dressed stone of the great thick wall as a man might stroke a favoured horse, ‘I can tell you, is fine stone, but your own quarry cannot meet our demand and we have gone further afield. Both we,’ he used the inclusive pronoun, ‘and Abbot Reginald have our eye upon the same commodity. The price has thus risen.’ He spread his hands placatingly.

The sacrist was not appeased. ‘Surely, you can make changes, cut corners …’ His voice lost its authority and wavered as Elias’s brow darkened.

‘Cut corners,’ he growled, his affability discarded. ‘What would you have me build, Brother, an ornament to this House of God or a wall fit for you to piss against in the reredorter? And do not ask if I would cut corners with the pulleys and poles. I expect hard work from my men, but in return I try and ensure that as few as possible lose life or limb. Would you have me sacrifice them in the name of economy?’

The sacrist shook his head. ‘No, no, Master Elias. I would not, naturally … I mean …’ His voice trailed off in embarrassment, and he looked helplessly at his companions. Although their feet had not moved, they somehow managed to distance themselves from him, indicating that they were not party to his error of judgement. The trouble, thought Brother Remigius, forgivingly, was that any sacrist ended up covetous for his house, always seeking to keep, whereas an almoner was always giving.

Master Elias did not let his expression soften. He would not have done so even if his emotion had been an act, but on the subject of workmanship he held genuinely strong beliefs. What the sacrist had said was as heresy to him. Brother Remigius sought to mollify the master mason with soothing words, and if Master Elias did not actually believe them, he was at least happy to see the situation eased without having to concede his position. The cellarer took the opportunity to tug surreptitiously at the sacrist’s sleeve, and the pair of them withdrew. The sub-prior thought his brother obedientary had been less than politic, and moved the conversation on to safer topics. He actually found the work of the masons very interesting, and had seen examples of carving at Winchester which he could describe to Master Elias. Mason and monk spent some time in amicable discourse.

It was then that Eudo the Clerk appeared, without advertising his approach, from the direction of the gatehouse. It was amazing how he could flit like a silent, black moth. He acknowledged the master mason with an irritatingly gracious nod, but turned his attention to Brother Remigius. Master Elias was about to excuse himself, when realisation dawned as to who this was. He had an excellent visual memory and had seen that unctuous, self-satisfied face before. Where? Ely, Abingdon, Oxford? That was it … in Oxford. He tried to recall the name. Eustace, was it? No. Well, he was certainly the lord Bishop of Winchester’s man, and in Oxford rumour had been rife that he was always to be found where discord and deceit were hottest, and that he had an unfailing ability both to increase the temperature and to make sure that his master was on the side of the successful faction. Despite Henri de Blois, Bishop of Winchester, being the king’s brother, he had been quite prepared promote the empress’s claim while King Stephen had rotted in a Bristow dungeon, and then equally swift to return to his brother’s side when the tables had been turned and Stephen was once more in command. Master Elias did not think much of such inconstancy.

He himself believed that the Empress Maud had full right to be Lady of the English, given that was her father’s wish. He had thought well, in a distant and respectful way, of the late King Henry. He had even seen him once, while still a journeyman, when the king had viewed the building upon which he was working. It had been but a stolen glance before his superior clouted him about the ear for lack of attention, but it had left an impression. Pity it was that a king with such fruitful loins had sired but two legitimate offspring, and that the Prince William should have met an early death at sea. But the king had named his daughter, the widowed empress of the Holy Roman Empire, as his heir, and the baronage had sworn fealty. They had no cause, in Master Elias’s opinion, to break that oath and accept King Henry’s nephew as king. Some had come to regret their choice and raised an army for the empress. Elias was no warrior, nor of elevated class, but he had found that his work took him further afield than most in the realm, and that a man of quick eye and attentive ear could learn much. Master Elias was certainly not, in his own view, a spy. He did not plot or listen at windows; did not bribe or threaten to reveal his knowledge. He simply made note of interesting things and passed such information to men he knew to be both discreet and firmly on the side of the Empress Maud.

He was not paying attention to the cowled pair while he thought. Ecclesiastical business was usually far too parochial and small-minded to be of interest, but something in Brother Remigius’s tone jarred. Having just been speaking with him, Master Elias could easily detect the new chill and dislike in his voice, and, surprisingly, a heavy overtone of fear. He stared at the sub-prior, frowning, and then suddenly realised that the lord bishop’s clerk was watching him. He coloured, and, for an instant, the ghost of a smile flickered over the clerk’s face. Brother Remigius looked distinctly uncomfortable. Master Elias was about to withdraw when the clerk addressed him.

‘You have travelled a way west from your usual haunts, Master Mason. I last recall you in Oxford, at St Frideswide’s.’

Eudo the Clerk had as good a memory for faces and voices as the master mason’s, if not better. It had taken barely a moment to drag his image from the filing system of memory, and as he spoke, Eudo was contemplating what use could be made of the man. He recalled the master mason as a Maudist, but quietly so, and Eudo wondered if he had come into Worcestershire with the aim of discovering information in an area where the supporters of king and empress overlapped. It would be prudent to discover if the big man was as sharp as a chisel or as dull as a mallet.

Master Elias was wary. ‘I came where the work was, Brother, and it is not so far from Oxford. As well work here as further north.’

Eudo inclined his head, with a suggestion of graciousness. ‘Indeed, the north can be as … difficult … in terms of strife between the king and the countess.’

Master Elias blinked in surprise. The Empress Maud, now married to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, still used her more exalted title and was not known as ‘countess’. The only people who gave her the title were a few of those covertly seeking her elevation to the throne of England as ‘Lady of the English’. He had heard it used as a signal among her supporters, but the lord Bishop of Winchester supported the king again, so what was his clerk up to?

‘I would be interested to see the work you have undertaken here,’ continued the clerk. ‘Perhaps I might visit your workshop at some convenient time. We must arrange it.’ He nodded a dismissal, and Master Elias, who would normally have bristled at such treatment, meekly withdrew, his mind whirling. Brother Eudo turned to the sub-prior. ‘Now, Brother Remigius, we have, I think, much to discuss. Perhaps the cool of the cloister would be more pleasant.’

The sub-prior gave him a look that implied he would find standing in a snake pit infinitely more ‘pleasant’ than further conversation with Eudo the Clerk, but went with him nonetheless.

In the cool of the abbot’s parlour, Abbot William of Pershore was conducting negotiations with two women, although one seemed merely there as silent support.

‘It was not thought too great a thing to ask, Father Abbot, that a small relic of the blessed saint should return to the sorority in which her own sister lived.’

The speaker was a Benedictine nun, reverent in word, but with her own obvious authority. Her voice was low and controlled, as controlled as every other aspect of her, from her immaculate tidiness to her straight back as she sat, and the precise folding of her hands beneath her scapular.

Abbot William considered carefully. The Benedictine nuns of Romsey were offering both coin and a fine manuscript, copied and embellished by one of the finest illustrators of the Winchester school, in exchange for the bone of a finger of St Eadburga, who lay within the gilded reliquary in her chapel in the abbey church. That they were prepared to offer much for so little was proof of their eagerness to claim a part of the saint.