9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Bow Street Rivals

- Sprache: Englisch

In this first instalment of the Bow Street Rivals series a riot breaks out in Dartmoor prison, enabling some American inmates to escape. The twin detectives Peter and Paul Skillen catch wind of a projected assassination but the target is unknown. Trouble ensues when a woman from the Home Office vanishes; a mysterious lady turns up at the archery shooting gallery; and Paul's gambling addiction worsens . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

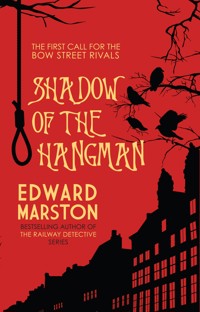

Shadow of the Hangman

EDWARD MARSTON

With love and thanks to my literary agent, Jane Conway-Gordon, who liked the idea behind this book when I first pitched it to her and who encouraged me to develop it with all guns blazing

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

1815

Ned Greet was a short, slight, wiry man with long, straggly hair and the face of a startled rabbit. He was also one of the most prolific and successful burglars in London. Confident that it would never be claimed, he’d watched with amusement as the reward for his capture increased steadily in value. Most criminals in his position would have decided to lie low for a while but Greet was not going to let anything interfere with his lucrative occupation. Risk excited him. It made his blood race. As he set off into the cloying darkness of the capital that night, therefore, he was tingling with anticipatory joy. His target was a warehouse, piled high with exotic spices. Even small quantities of them would fetch a high price. Before he tried to break into the building, he walked furtively around it to make sure that no night watchmen were on patrol. When he felt that it was safe to continue, Greet used a jemmy to prise open the window at the rear of the warehouse. Climbing in was the work of seconds. Once he was there, he lifted the shutter on his lantern and let its light spill out. Temptation was all around him.

Taking a deep breath, he inhaled a dizzying compound of aromas.

What he could smell was pure profit.

Opening the large leather bag slung over his shoulder, he took out a handful of small canvas ones and began to fill each of them in turn from a different sack. Peppercorn, cassia, cinnamon, turmeric, cardamom and other spices were carefully gathered then placed into the leather bag. Absorbed in his work, Greet moved swiftly and deftly, assessing the value of his haul as he went along. He was in his element. Greet was only aware that he had company when he heard a voice behind him.

‘You won’t need those in prison, Ned.’

The burglar swung round to face a tall, lean, well-dressed man in his thirties whose handsome features were illumined by the lantern. Apparently unarmed, the newcomer seemed completely at ease.

‘Who’re you?’ demanded Greet.

‘I’m the person who will have the supreme pleasure of collecting the reward money for your arrest,’ said the other, raising his hat in a mock greeting. ‘I could have apprehended you earlier, of course, but I’m a patient fellow so I waited until there was an appreciable sum on offer. Your career as a thief is decisively over, I’m afraid. You were too greedy, Ned, and that brought you to my attention.’

Greet was shocked. ‘You’ve been following me?’

‘Let’s just say that I’ve been keeping a friendly eye on you.’

‘But I always cover my tracks.’

‘Watching you doing it has been a rare entertainment.’

Greet was cornered. He was shaken by the news that his escapades had been under scrutiny by someone else. He peered intently at the man. The stranger looked bigger and stronger than him so Greet judged that he would come off worse in a fight. Instead, therefore, he snatched the dagger from his belt and lunged. But the man was far too quick for him, shooting out a hand and squeezing Greet’s wrist so hard that he let out a cry of pain and dropped the weapon on the floor. The man kicked it out of reach. Releasing his hold, he clicked his tongue disapprovingly.

‘That was ill-advised, Ned. Try anything like that again,’ he warned, ‘and I’ll be obliged to kill you, albeit with regret.’

Cowering before him and rubbing his wrist, Greet changed tack.

‘There’s enough here for both of us, sir,’ he said, with an obsequious grin. ‘You can take your pick. I’ll help you fill the bags. Choose wisely and we can both get away with a small fortune. Spices are rich pickings.’ He added with a gesture that took in the whole warehouse. ‘I know where to get the very best price for them.’

‘That’s of no consequence,’ said the man.

‘Don’t you like money?’

‘Why, yes, I love it as much as anyone – but what I’d like even more is the satisfaction of seeing you behind bars in Newgate. You’ll enjoy different odours there, I warrant – some of the most pungent engendered by your own miserable body.’

Greet was indignant. ‘I don’t belong in prison.’

‘Then you shouldn’t have taken up thievery.’

‘I’ve a wife and family to support.’

‘They must look elsewhere for sustenance.’

‘Look,’ said the other, panic setting in, ‘I’ll strike a bargain with you, sir. I’ll steal nothing. I leave it all for you.’

‘That’s uncommonly generous of you,’ said the man, laughing, ‘but I spy a problem. These spices are not yours to give away so freely. Morally and legally, they belong to someone else.’

‘They’re yours for the taking.’

‘The same is equally true of you.’

‘No, no,’ said Greet, holding up both palms as his companion took a step towards him. ‘Consider this, sir. I can see by your appearance that you have an excellent tailor. Seize the spoils on offer here and you can buy a dozen new suits from him in the latest fashion.’

‘I have apparel enough to content me.’

Greet was dismayed. ‘Is there nothing that’ll tempt you?’

‘I seek only your arrest.’

‘Then we must part as enemies.’

The burglar was like lightning this time. Thrusting a hand into an open sack, he grabbed a fistful of pepper and threw it straight into the man’s eyes, blinding him momentarily. Greet took to his heels, darting off into the gloom in search of escape. When he came to a staircase, he ran up it as fast as he could. The sound of the burglar’s feet clacking on the wooden steps told the stranger exactly where his quarry had gone. With the lantern in his hand, he set off in pursuit. Finding the staircase, he began to ascend it but he got only halfway up before he had a glimpse of a blurred figure ahead of him. Greet had a sack of flour over his shoulder and he hurled it directly at the man, catching him in the chest, knocking the lantern from his grasp and sending him tumbling backwards down the steps.

Having disabled his attacker, Greet elected to cut his losses and get out of the warehouse altogether. He blundered along the upper floor. When he reached the door through which goods were winched up from below, he flung it wide open and jumped into the darkness, landing with cat-like ease on the ground below. To his utter amazement, he heard a metallic click as the shutter of a lantern was lifted and a pool of light was created. Greet found himself staring at the person he thought he’d just knocked down the stairs.

‘That’s impossible!’ he howled. ‘You can’t be in two places at once.’

The man beamed at him. ‘It appears that I can, Ned.’

CHAPTER TWO

Gully Ackford handed over the money then recorded the amount in his ledger. He was a big, well-built man in his fifties with the weathered look of a veteran soldier. His craggy face wore its customary smile.

‘That’s your share of the reward, Peter,’ he said. ‘By right, you should have had more because you actually arrested Ned Greet.’

‘It was my brother who flushed him out of the warehouse. If anyone deserves a larger slice, it ought to be Paul. He still has bruises from the encounter. But let’s not haggle over the takings,’ said Peter Skillen, pocketing his money. ‘Greet’s arrest was the work of a team. You found out where the wretch lived, Jem trailed him for us, then Paul and I stepped in to catch him in the act.’

‘I’ve watched Greet for a long time. He’s like so many of his breed – a Tyburn blossom, who was always going to end up as a gallows-bird. He’ll be dancing a jig for the hangman before too long.’

Peter was sympathetic. ‘I’d sooner the fellow were transported, Gully. No man should have his neck stretched for stealing a piece of ginger and a few cloves.’

‘I disagree,’ said Ackford, firmly. ‘You’re too soft-hearted, Peter. Thieves are vermin. If they’re not exterminated, they’ll steal the clothes off our backs. Besides,’ he went on, ‘Greet was not there for tiny samples. According to Paul, the villain grabbed enough in his grasping hands to set himself up as a spice merchant.’

‘His punishment will still be too great for the crime.’

‘Robbing the warehouse was only the latest of his offences. Ned Greet has been the busiest thief in London. We’ll be applauded for netting the rogue at last and a lot of his victims will be there to cheer at his execution.’

‘Instead of blaming the burglar,’ said Peter, wryly, ‘they should instead chide themselves for failing to protect their property with sufficient care. If people wish to keep thievery at bay, vigilance must be constant.’

Peter Skillen was a mirror image of his twin brother, Paul. They were not simply identical in outward appearances, their facial expressions and habitual gestures were also interchangeable. Their voices were so similar in timbre and pitch that even Gully Ackford – who’d known them for many years – sometimes had difficulty telling one from the other. What set them apart were profound differences of character.

‘What comes next?’ asked Peter.

‘Need you ask? What comes next is the joy of spending that money I’ve just given you. If you’re short of ideas on how to do so, I daresay that Charlotte will provide some suggestions.’

Peter grinned. ‘My wife has a gift for shopping tirelessly – even if it’s to buy things of which we have no need whatsoever.’

‘Then give her free rein. When that bounty is fully spent, there’ll be plenty more to make our purses bulge. As our fame spreads, commissions will begin to flood in. Banks are always in search of our talents and there is unlimited work guarding the more fearful members of the aristocracy. We’ll never starve, Peter.’

They were in one of the rooms at the rear of the shooting gallery owned by Ackford. Used by a variety of clients, it offered instruction in shooting, archery, fencing and boxing. Ackford was an expert in all four disciplines. Among his most regular customers were the twin brothers, who liked to keep their fighting skills in good repair in case they were needed. As a young soldier, Ackford had tasted defeat at the hands of American rebels at Yorktown. Against Napoleon’s armies, by contrast, he’d savoured victory in a British uniform. Peter and Paul Skillen valued his experience. He was a demanding tutor and a man with a rasping authority when it was necessary to impose his will.

‘What will your brother do with his share?’ asked Ackford.

‘I daresay that Paul will spend every penny at some gambling haunt.’

‘What if he wins at cards for a change?’

‘That’s as likely as his finding the woman of his dreams.’

‘But he already has found her. The trouble is that she married you instead.’

‘Oh, I think he’s outgrown that disappointment,’ said Peter with a smile. ‘When Charlotte was no longer available, he quickly discovered willing substitutes and has been working his way through them ever since. They change so fast that I can never remember their names.’

‘Paul needs to settle down.’

‘He has done so frequently, Gully – but never for very long.’ They shared a laugh. ‘Don’t try to change my brother. That’s beyond the capability of any man. It would be like telling the moon not to shine or stopping the flow of the Thames. Paul is a force of nature. He’ll go his own way regardless.’

Paul Skillen looked through the front window in time to see a figure hurtling towards the house. He identified Jem Huckvale by his speed rather than by any physical features. Short, compact and holding on to his hat with one hand, Huckvale was known for his prowess as an athlete and his skill at weaving through a crowd at full pelt. He would never walk if he could trot, and he would never do that if he could run flat out. When he reached the house, he paused to catch his breath then rang the bell. A servant admitted him then showed him into the drawing room.

‘Come in, Jem,’ said Paul, embracing him warmly. ‘I hope that you’ve brought what I am expecting.’

‘I have, indeed,’ replied the other, taking a fat purse from his coat pocket. ‘Gully has divided the reward and I’m delivering your share.’

‘Then you are doubly welcome.’

‘He sends his regards.’

Receiving the purse from him, Paul tipped its contents onto a table and spread out the banknotes and sovereigns. He lifted a handful of coins and feasted his gaze on them before letting them cascade back down on to the pile. Huckvale, meanwhile, had removed his hat and stood waiting politely. As well as being Ackford’s assistant at the shooting gallery, he was a trusted messenger with wings on his heels. Though he looked to be no more than fifteen, Huckvale was ten years older but the freshness of his face and his small physique disguised his true age.

‘This will help me to pay off my debts,’ said Paul, counting the money.’ He looked up. ‘Has Gully given you your share?’

‘Yes, and it’s far more than I deserve.’

‘No modesty, Jem – you played your part as well as any of us. Once we’d found out where Ned Greet lived, you shadowed him for weeks. That was dangerous work and should be recognised with payment.’

‘It’s a privilege to serve you and Peter,’ said Huckvale, admiringly. ‘My needs are limited and my wages at the shooting gallery are more than enough for me. Being able to work alongside you and your brother is the real recompense.’

‘Thank you.’

‘There’s always so much excitement.’

‘Is that what you call it?’ asked Paul with a hollow laugh. ‘There’s no excitement in being knocked down a flight of stairs by a bag of flour, I do assure you. It was a miracle that I came off with nothing worse than bruises.’

‘We caught him, that’s the main thing.’

‘No, Jem, we made good money for doing so. That’s what is really important.’

‘Peter says that we’re helping to cleanse the city of crime.’

Paul shrugged. ‘If my brother wants to view it as a moral crusade, so be it. I take a more practical view. Every time we deliver a villain to the magistrates, we get paid for our efforts and that enables us to indulge ourselves. Peter, of course, has turned his back on the multiple pleasures of the capital but I intend to enjoy them to the full – and that costs money. Unbeknownst to him, Ned Greet has both cleared my debts and supplied me with the requisite funds for gambling anew.’

‘Greet has other thing on his mind at the moment, Paul.’

‘Yes, he’s having nightmares about Tyburn!’

His harsh laughter echoed around the room. Like most people, Huckvale couldn’t tell the twins apart simply by looking at them. It was only when they began to express a point of view that he saw how dissimilar they really were. Peter was calm, reasonable and compassionate. His brother, on the other hand, was a man of trenchant opinions, reckless, irresponsible and wayward in his private life. Huckvale was devoted to both of them but – without really understanding why – the one he really idolised was Paul Skillen.

‘News of the arrest is in the newspapers,’ he said.

Paul curled a lip. ‘I make a point of not reading them.’

‘It’s a way of building our reputation.’

‘That will please Gully.’

‘It pleases everyone who wishes to uphold the law.’

‘I can think of a notable exception, Jem.’

‘Oh – who might that be, pray?’

‘I’m talking about the man who’s been hunting Ned Greet as long as we have.’

‘Micah Yeomans?’

‘He’ll have seen the fellow as his legitimate prize. After all, Micah is a Bow Street Runner. He thinks that gives him a monopoly on justice. Our success will make him seethe,’ said Paul with wicked satisfaction. ‘Micah Yeomans will be livid when he realises that we are the best thief-catchers in England.’

‘The scheming devils!’ roared Yeomans, holding the newspaper with trembling hands. ‘The Skillen brothers have had the gall to do our job for us. They’ve caught Ned Greet.’ Scrunching up the newspaper, he flung it aside. ‘Why didn’t we get to him first?’

‘We were too slow,’ said Alfred Hale.

‘I blame you for that.’

‘I did my best.’

‘Patently, it was woefully inadequate,’ said Yeomans with withering scorn. ‘We keep a whole army of informers. Why could none of them earn their money and tell us where Greet was hiding?’

‘They did earn their money,’ suggested Hale. ‘Ned paid them more to keep their mouths shut than we paid them to keep their eyes open.’

‘Then how did those loathsome twins manage to track him down?’

‘That’s a secret I’d love to know, Micah.’

‘You failed me again, Alfred. You’ve no right to call yourself a Runner.’

‘I strive to please.’

‘Ha! There are times when your incompetence disgusts me.’

Hale was about to point out that Yeomans had been equally incompetent when he remembered what happened when he last challenged the senior man. It was safer to accept the rebuke and lower his head to his chest.

Nature had been unkind to Yeomans, giving him a face of unsurpassable ugliness with a misshapen nose competing for dominance against a pair of huge, angry green eyes, two monstrous bushy eyebrows and a long slit of a mouth from which a row of yellow teeth protruded. Even in repose he looked grotesque. When roused, as he was now, Yeomans was positively fearsome. A former blacksmith, he was a big, hulking man with powerful fists that were well known in the criminal fraternity. Hale was a solid man of medium height but he looked puny beside his companion. Both were in their forties with long, distinguished records as Principal Officers of Bow Street. They hated rivals.

‘The Skillen brothers live off blood money,’ said Yeomans, contemptuously.

‘We’ve had our share of that in the past,’ Hale reminded him.

‘Hold your tongue!’

‘It’s true, Micah.’

‘We have legal authority. They are floundering amateurs.’

‘Then why do they always show us up by harvesting our crop?’

‘They’ve trespassed on our land far too long,’ said Yeomans through gritted teeth. ‘It’s time to teach them a lesson, Alfred. Nobody can steal from us with impunity, least of all that pair of popinjays.’ His eyes blazed. ‘I want revenge.’

CHAPTER THREE

‘O’Gara is behind this,’ said Shortland, bitterly.

‘We don’t even know if he’s still in the prison, sir.’

‘He’s here, Lieutenant. I feel it.’

‘Then why have we never seen him?’

‘They’re hiding him somewhere. O’Gara’s been a confounded nuisance since he first arrived. He’s always trying to stir them up to mutiny and it looks as if he’s finally succeeded. We should have locked him in the Black Hole and left him to rot.’

‘The men did have a legitimate grievance,’ argued Reed. ‘The food contractor delivered a consignment of damaged hard tack that was almost inedible.’

‘That problem was solved yesterday,’ said Shortland, curtly. ‘Fresh bread was brought in. Unfortunately, it didn’t satisfy this rabble. They’re determined to cause trouble and it’s being orchestrated by Tom O’Gara.’

‘He’s only one of thousands of prisoners, sir, so it’s wrong to single him out. They all want the same thing. The war against the United States has ended. They’re demanding release.’

‘We run this prison, Lieutenant – not a mob of American sailors.’

They were viewing the situation with increasing disquiet. Hundreds of prisoners were milling around the yard. The sense of resentment was tangible. Voices were raised, fists were bunched, and more and more prisoners joined the melee. Captain Thomas Shortland of the Royal Navy had been governor of Dartmoor for less than two years and he hated the bleak, unforgiving, isolated prison. He was determined to exert control but the strict discipline he imposed had only served to create anger and vocal resistance. It seemed now as if a full-scale riot was about to break out.

A soldier came running breathlessly towards the governor.

‘They’re hacking a hole through to the barrack yard, sir!’ he yelled.

‘I was right,’ decided Shortland. ‘It is a plot.’ He swung round to face Reed. ‘Ring the alarm bell, Lieutenant. Rouse the whole garrison.’

‘There’s more to report,’ gabbled the soldier as Reed rushed off. ‘Someone has smashed a gate chain with an iron bar. Prisoners are flooding into the market square. They’re ignoring all commands.’

‘Then they’ll have to be taught a lesson.’

Events moved swiftly. The alarm bell clanged and the soldiers grabbed their muskets before running out of the barrack yard. Bayonets fixed and lines formed, they faced the horde of jeering prisoners. Shortland first tried to persuade the crowd to return to their quarters but his voice went unheard in the pandemonium. He resorted instead to coercion and ordered a charge. Though hopelessly outnumbered, the soldiers surged across the yard, their gleaming bayonets driving many of the prisoners back. Those near the gate continued to taunt their guards who responded by firing a volley over their heads. Enraged by the tactic, the prisoners fought back with ferocity, throwing stones, lumps of turf and anything else they could lay their hands on.

Battle had been joined.

The next volley was aimed directly at the seething mass of prisoners, killing some outright and wounding many others. Retreating in panic, the men bumped into each other in a wild bid to escape. Muskets continued to fire and more victims fell to the ground. It was a massacre. The yard was soon covered with bodies and stained with blood. Eventually, the shooting stopped and the hospital surgeon was able to rush forwards to examine the wounded. There were over sixty of them, some with serious injuries. Seven prisoners were already dead. Forced and frightened back into their quarters, the rest of the men were howling in protest. The tumult was deafening and the sense of outrage was palpable.

Horrified by what he’d seen, Lieutenant Reed sought out the governor.

‘There was no need to fire directly at them, sir,’ he complained.

‘They asked for it,’ said Shortland, unrepentantly.

‘We’ll have even more trouble from them now.’

‘They had to be reminded who was in charge, Lieutenant. We were up against an insurrection. Only force would quell it.’

‘We killed unarmed prisoners.’

‘It was done under severe provocation. This was an organised revolt. It had to be stopped in its tracks. And – God willing – there might be a bonus for us.’ Shortland smiled hopefully. ‘One of the dead men may turn out to be Tom O’Gara.’

Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, studied the report with unease. As Home Secretary, he did not have direct control over prisons but, since he was responsible for public safety and was the ultimate authority on the regulation of foreigners, an account of the Dartmoor riot had been sent to him. When he finished reading the document, he summoned Bernard Grocott, one of his undersecretaries.

‘There’s been a mutiny at Dartmoor,’ he said.

‘Has it been suppressed?’

‘Yes it has, but with dire consequences.’ He handed the report over. ‘See for yourself. It’s dispiriting.’

Grocott nodded then read the document with a searching eye. The elegant calligraphy yielded up a grim story and he clicked his tongue in disapproval. He was a short, fleshy man in his forties with a mask of permanent anxiety etched into his face. His eyebrows raised in consternation.

‘This is disturbing intelligence, my lord.’

‘I’d like to know more detail.’

‘There’s detail enough for us to form a judgement.’

‘That’s my concern,’ said Sidmouth. ‘Any judgement would be premature. At the moment, we only have one side of the argument. Far be it for me to take up cudgels on behalf of American prisoners of war, but they must have had cause to rebel in the way that they apparently did.’

An image of George Washington popped up in the undersecretary’s mind.

‘Americans are seasoned in rebellion, as we know to our cost.’

‘That’s a valid point.’

‘I’m tempted to say that it’s in the nature of the beast.’

‘There’ll have to be a full investigation.’

‘It’s not the first trouble we’ve had in Dartmoor,’ said Grocott, putting the report back on the desk. ‘When thousands of French prisoners were held there, they were always voicing complaints even though all kinds of concessions had been granted to them. They ran their own courts, meted out punishments, were allowed to buy food from a prison market and had both a theatre and a gambling house to while away the time.’

‘Gambling was at the root of many of the disturbances there,’ said Sidmouth, ‘and doubtless it still is. If men bet and lose their entire food rations, they are bound to become desperate. Then, of course, there’s the prevalence of disease in that Godforsaken place on the moors. The mortality rate is shameful. Prisoners have tried to escape simply to stay alive.’

‘That doesn’t make mutiny acceptable, my lord.’

‘Quite so, Grocott, quite so – but we have to allow for the fact that the men held there are under duress. French prisoners have money to soften the impact of the harsh conditions. The Americans, by and large, have none. They suffer.’

Now in his later fifties, Sidmouth was a tall, slim, dignified man worn down by the constant pressure of affairs of state. Three years as Prime Minister had been especially burdensome, winning him few friends and a legion of detractors. Yet he was a kind, tolerant, unfailingly courteous man with greater abilities than his enemies recognised. By instinct, he was also scrupulously fair and liked to weigh the evidence regarding a particular issue before reaching a conclusion.

‘I’d like to know more about this business,’ he said. ‘The war with the United States is, blessedly, finally over. These men should not be fretting away their days behind prison walls. They should be sailing back home.’

‘The Peace of Ghent has been ratified,’ Grocott pointed out. ‘What is holding them up is the lack of transport. The sooner they are shipped out, the sooner we shall stop having alarming reports from Dartmoor.’

‘It’s a place of unrelieved misery.’

His companion grimaced. ‘It was ever thus, my lord.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean that the Home Office is principally the recipient of unending bad news.’ He struck a pose. ‘After a long war, Britain is in a parlous state. We have a gigantic national debt, falling revenue, a disordered currency, chronic unemployment and whole sections of our population are on the brink of rebellion. Only yesterday, for instance, we heard of more violence in factories where new machinery has been installed and secret societies are being formed with the sole purpose of undermining the government. On whom are these problems dropped? It is always us.’

‘You are right,’ agreed Sidmouth, sadly. ‘Almost all the troubles of the nation are dumped on us. I own that there are times when I feel that the Home Office is nothing but a glorified wastepaper basket into which every other department of government can throw its unwanted litter. We are truly beleaguered.’ He sat back wearily, then remembered something. ‘Talking of wastepaper baskets, I couldn’t help noticing that mine has not been emptied today.’

‘We’ve all suffered that inconvenience, my lord.’

‘What happened to our necessary woman?’

‘She appears to have been lax in her duties.’

‘That’s highly uncharacteristic of Horner. Someone must tax her. When one is the nation’s largest wastepaper basket,’ he went on with a rare attempt at humour, ‘one does at least expect to be emptied on a daily basis.’

Tom O’Gara was still furious about what had happened at Dartmoor. When the soldiers had fired their first murderous volley, he’d seen defenceless comrades fall to the ground. Unlike most of the prisoners, O’Gara had not fled back to his quarters. He and his friend, Moses Dagg, had taken advantage of the confusion to climb a picket fence, find a hiding place behind the hospital and stay there until nightfall. Under cover of darkness, they’d made their way to the Military Walk – the gap between the high, concentric stone walls that encircled the prison – and bided their time until the sentries on the wooden platforms went past. They then clambered up the steps to the top of the perimeter wall. After dropping to the ground beyond, they’d run as if the hounds of hell were baying at their heels. The next couple of days were spent dodging the search parties who’d come out looking for them.

‘They’ll never get me back inside that place,’ vowed O’Gara.

‘Nor me,’ said Dagg.

‘It ought to be burnt to the ground – and Captain Shortland with it.’

‘I’d enjoy dancing round the blaze.’

‘So would I, Moses.’

O’Gara was a sturdy Irish-American in his late twenties with a mop of dark hair and a fringe beard. He’d rubbed his face, arms and hands liberally with dirt so that he could be concealed in the part of the prison where the black sailors had been segregated. One of them, Moses Dagg, had been his shipmate when their vessel was captured. Both had been kept in custody in Plymouth before being transferred to Dartmoor. Conditions had been so appalling there that O’Gara acted as a spokesman for the other prisoners, voicing his demands with such insistence that he aroused the ire of the governor. Instead of winning concessions, therefore, O’Gara was promptly sent off to the Black Hole, a punishment cell made entirely of stone blocks. There was no natural light and only a tiny grille for ventilation. O’Gara was forced to sleep on the bare floor. The sparse rations were poked in through an aperture in the reinforced metal door. Though the maximum sentence was ten days in the Black Hole, the vindictive governor kept him in there for a fortnight. Instead of breaking his spirit, however, all that Captain Shortland did was to strengthen O’Gara’s will to resist.

‘Someone should be told the truth,’ said Dagg.

‘They will be.’

‘But who would listen to us?’

‘We have to make them listen, Moses.’

‘How do we do that?’

‘First of all, we have to get well clear of Devon,’ said O’Gara. ‘We’ll have to steal to eat here. The best place for food and protection is London. I’ve a cousin there who’ll take us in.’

‘He may take you in, Tom, but do I look like an Irishman?’

‘Yes – I’ll tell them you’re a lad from Killarney who caught too much sun.’

Dagg shook with mirth and punched his friend playfully on the shoulder. Adversity had deepened the bonds between them. Dagg was a solid young man with bulging muscles and a ready grin. When O’Gara’s persistent protests had aroused the governor’s ire, he put himself in grave danger. He became Shortland’s scapegoat and was blamed for every sign of unrest. Dagg had sheltered his friend in the segregated area and thereby saved his life.

‘Well,’ said Dagg, chuckling, ‘if you can be a black man, then I can be an Irish leprechaun. How do we get to London, Tom?’

‘We’ll do what we know best.’

‘And what’s that?’

‘We’re sailors, aren’t we?’

‘Yes, we are.’

‘Then let’s get afloat. When we reach the coast, we’ll steal a boat and plot a course to London. Once we have a refuge, we can tell the truth about Dartmoor.’

‘Who will we speak to?’

‘Well, it won’t be the Transport Office,’ said O’Gara, vehemently. ‘They’re supposed to look after prisoners of war but they answer to the British Admiralty and we’ve seen the way they treat us.’

‘Yes, they put that monster, Shortland, in charge of Dartmoor.’

‘We’d never get fair treatment from the Royal Navy so we’ll have to go above their heads. We’ve got a tale to tell, Moses, and we must tell it loud and clear. The person who really needs to hear it is the Prime Minister himself.’

CHAPTER FOUR

After a busy morning teaching the noble art of self-defence to a couple of young blades, Gully Ackford adjourned to the room at the rear of the shooting gallery and sat down gratefully behind the desk. Within minutes there was a respectful tap on the door then it opened so that Jem Huckvale could usher a stranger into the room before slipping out again. The newcomer was a stout, pale-faced individual of middle years with an air of prosperity about him. He introduced himself as Everett Hobday.

‘I need your help, Mr Ackford.’

‘With respect, sir,’ said Ackford, noting the man’s paunch, ‘you are not exactly built for the boxing ring. It would be folly on my part to attempt to persuade you otherwise. I take it, therefore, that you seek instruction of another kind.’

‘I’ve come to engage the services of your detectives.’

‘Ah, I see.’

‘I read the newspaper report of their latest success and decided that they are the men for me. I want the best and I’m prepared to pay accordingly.’

‘How can we be of assistance to you?’

Hobday explained that he was leaving London the following day and was taking the servants to his country residence. The last time he did that, his town house in Mayfair had been burgled. He needed someone to look after it while he was away. His request was not unusual. Peter and Paul Skillen had acted as night watchmen before in some of the more opulent houses. The difference this time was that their payment would be unduly generous. Hobday was well spoken and plausible. As proof of his honesty, he offered an appreciable deposit.

‘Then I gratefully accept it, sir,’ said Ackford, taking the money. ‘Though one question – I have to confess – does remain.’

‘What is it?’

‘Why not leave a servant at the house? It would be a much cheaper solution. A servant would know the property well, whereas my men do not.’

‘I tried that once before,’ said Hobday with a sigh, ‘and it ended in disaster. The servant whom I left alone to guard the house was surprised by the burglars and given the beating of his life. I could never subject an employee of mine to that fate again. This is a task for experienced men like yours. Since they were trained by you, they will be proficient in the use of arms.’

‘They are proficient in everything, I do assure you.’

‘That is the very reason which brought me here.’

‘How long will you be away, sir?’

‘Four or five days – I’ll send word of my return. Needless to say,’ he added, ‘if my home is broken into again, and if the rogues in question have a price on their heads, your detectives will be able to claim every penny of the reward.’

‘You speak as if you expect a burglary.’

‘Houses are watched carefully in Mayfair. Properties that are left empty and unprotected are fair game for thieves. What I am really paying for, you see, is peace of mind. I wish to be able to leave London without any tremors.’

‘Then you shall, sir,’ promised Ackford. ‘All that we need is an address and a key to the property. As soon as you quit the house, my men will act as sentries.’

Hobday thanked him profusely. After handing over a latchkey and giving him the relevant details, he left the gallery with a smile of satisfaction.

Ackford immediately summoned Jem Huckvale.

‘Follow the gentleman who just left,’ he ordered.

‘Where is he going?’

‘He claims to have a house in Upper Brook Street.’

‘Do you have doubts about that, Mr Ackford?’

‘It’s always wise to make certain that a client is telling the truth.’

‘What’s his name?’

‘He says that it’s Everett Hobday – find out if it really is.’

‘I will.’

Turning on his heel, Jem Huckvale ran swiftly out into the street.

Viscount Sidmouth found the news so disturbing that he leapt up from his chair.

‘Horner has disappeared?’

‘Yes,’ confirmed Grocott. ‘The alarm was raised by her sister, a Mrs Esther Ricks. It seems that they were due to meet yesterday evening but Horner did not turn up. Her sister went straight to her house and was told by the landlady that she had not come back the previous night.’

‘Well,’ said Sidmouth, resuming his seat, ‘that explains another day of rooms that were not cleaned and wastepaper baskets that were not emptied. It’s all very mysterious. I cannot believe that Horner would desert her post without giving us prior warning. She’s renowned for her dependability.’

‘Might she have been taken ill, do you suppose?’

‘That’s idle speculation. The salient fact is that she is simply not here.’ He scratched his chin. ‘Well, it’s taught us one thing.’

‘What’s that, my lord?’

‘One never realises how necessary a necessary woman is until she vanishes.’

‘I agree. I’m starting to feel bereft already.’

Sidmouth became businesslike. ‘In the short term,’ he said, ‘Horner must be replaced. I will put that task in your capable hands.’

‘Leave it with me.’

‘There are eighteen of us employed in this building. Apart from ourselves and the permanent undersecretary, there’s your fellow undersecretary, a chief clerk, four senior clerks and eight junior clerks. We all have our separate functions but I venture to suggest that our female colleague, Horner, is just as important as any of us.’

‘I’d endorse that.’

‘In having her to look after us, we’ve been thoroughly spoilt.’

‘Where might she have gone?’

‘It’s a puzzle that must be solved without hesitation. I’ll send word to the one man who will be able to track her down’

‘And who might that be, my lord?’

‘His name is Peter Skillen and I made great use of him as a spy behind enemy lines in France. Fortunately, he was fluent in the language, unlike some of the men I foolishly engaged. They paid with their lives. Now that the war is finally over – and Napoleon has been exiled – Skillen is working as a detective with his brother.’

‘He sounds like the ideal man.’

‘Your job is to find me the ideal woman, Grocott. I like the smell of polish when I come in here first thing in the morning. It’s been sadly lacking.’

‘Wherever you turn in this building, Horner’s absence is evident.’

Grocott was about to leave when the Home Secretary called him back. Sidmouth snatched up a letter from his desk and brandished it in the air.

‘As for that other matter we discussed,’ he said, ‘I’ve received a letter from Captain Shortland, the governor of Dartmoor.’

‘What’s its import?’

‘Quite naturally, he’s keen to speak up in his own defence.’

‘Does he say how the riot began?’

‘Oh, yes,’ replied Sidmouth. ‘The governor knows the person behind it. He’s a troublemaker by the name of Thomas O’Gara, or so it appears. The fellow not only whipped the other prisoners into a frenzy of protest, he used the ensuing chaos as a means of escaping Dartmoor. Shortland discovered that O’Gara had been hiding with a group of black prisoners, one of whom fled with him. They’re still hunting the pair.’

‘Can the whole episode be blamed on a single culprit?’

‘No, and that’s not what Shortland is doing. He freely admits that other factors need to be taken into account. Passions have been running high behind those walls for a considerable time.’

‘What about the decision to open fire?’

‘The governor argues that it was unavoidable.’

‘How does he describe it?’

‘In the same way that it will probably be described after the official inquiry,’ said Sidmouth, solemnly. ‘Captain Shortland insists that it was a case of justifiable homicide.’

When he left the shooting gallery, Hobday had climbed into the saddle of a bay mare and set off towards Leicester Square at a steady trot. Jem Huckvale was trailing him, close enough to keep him within sight but far enough behind to arouse no suspicion in the rider. Even when the horse was kicked into a canter, Huckvale kept pace with it, lengthening his stride and maintaining a good rhythm. Though the streets were filled with pedestrians, vendors, horse-drawn vehicles and other potential hazards, he was not hampered in any way. Huckvale glided around them all as if they were not there.

The rider zigzagged his way towards Mayfair and eventually reached Upper Brook Street. Stopping at a house on the corner, he dismounted and led the animal to the stable at the rear. Huckvale lurked in a doorway and watched from a distance. At length, the man reappeared and was let into the house through the front door. Since there was nobody else in the street, Huckvale waited patiently. His vigil was finally rewarded. An elderly man emerged from a house several doors away. Huckvale ran across to him and raised his hat politely.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ he said, ‘but I’m looking for Mr Hobday. I believe that he owns a house in Upper Brook Street. Do you happen to know which one it is?’

‘Why, yes,’ replied the man, pointing a finger. ‘Hobday lives in that house on the corner.’

‘Thank you for your help, sir.’

While the man went off in the opposite direction, Huckvale walked towards the house on the corner. Upper Brook Street extended from Grosvenor Square to Park Lane and contained some fine residences. Only a wealthy man could buy property there. Patently, Hobday was one of them. His identity had been confirmed and he lived in the address he’d specified. The mission was over. Huckvale felt that he’d discharged his duty and could run back to the shooting gallery with reassuring news that their new client was genuine. Before he could move, however, he heard the warning voice of Gully Ackford in his ear. It was loud and peremptory, Check everything twice.

It was an article of faith with his employer. Huckvale had to pay heed.

‘Check everything twice.’

Ackford treated his assistant like a son but he could be ruthless when his orders were disobeyed. Huckvale had incurred his displeasure once before and it had been such a disagreeable experience that he had no wish to repeat it.

With a philosophical shrug, therefore, he resumed his vigil.

Peter Skillen was in the drawing room with his wife when the letter arrived. He recognised the seal at once and broke it to open to read the missive.

‘It’s from the Home Secretary.’

‘He’s not going to send you back to France again, is he?’ asked Charlotte in mild alarm. ‘He stole you away from me far too much when the war was on.’

‘Absence makes the heart grow fonder, my love.’

‘Mine didn’t grow any fonder, Peter. It began to shrivel up with neglect.’

‘This is nothing to do with my activities in France.’

‘I’m relieved to hear it.’

‘The Home Secretary wants me to find a woman for him.’

‘Heavens!’ exclaimed Charlotte, bringing a hand to her mouth. ‘Does he expect you to become his pander? It’s a revolting suggestion. Apart from anything else, he’s a married man. What about his poor wife? This is a disgraceful commission, Peter. It’s demeaning.’ She stamped a foot for emphasis. ‘However powerful he may be, I forbid you to provide him with a mistress.’ Her husband laughed. ‘It’s not an occasion for levity.’

‘Viscount Sidmouth is not searching for a mistress,’ he said. ‘I know him well and I can vouch for the marital harmony he enjoys. No, the woman for whom I must search is the servant who cleans the Home Office. She has inexplicably disappeared.’

‘Oh, I see. I spoke too soon.’

Even when her face was puckered into an apology, Charlotte Skillen remained a beautiful young woman. Slim, shapely and of medium height, she had fair hair artfully arranged in curls. The colour of her morning dress matched her delicate complexion. Her husband kissed her gently on the forehead.

‘It was my fault for phrasing the request in the way that I did.’

‘You should still refuse this assignment.’

‘On what grounds could I possibly do that?’

‘Some paltry excuse will do for the Home Secretary,’ she said, airily. ‘The real reason you must turn his appeal down is that it’s beneath you. It is, Peter,’ she added before he could protest. ‘You and Paul have just caught one of the worst criminals in the city. It was an achievement worthy of your talents. Viscount Sidmouth must have a host of minions at his beck and call. Let one of them chase after this missing cleaner.’

‘Her name is Anne Horner.’

‘I don’t care what she is called.’

‘Supposing that it had been Moll Rooke?’

Charlotte was taken aback. ‘She’s one of our servants.’

‘How would you feel if Moll suddenly vanished into thin air? Would you stop me searching for her because it was too lowly a chore for me?’

‘No – of course not!’ she returned. ‘What an absurd question! Moll is a dear woman who has served us faithfully since we were married. I’d not only urge you to find her, I’d join the hunt myself.’

‘The Home Secretary obviously has equal regard for Mrs Horner. His letter talks of her loyalty and reliability. His fear is that something untoward has occurred. Not to put too fine a point on it, my love,’ he went on, ‘he cares for her safety and I find that admirable.’

She lowered her head. ‘I am rightly chastised, Peter.’ She looked up at him with a smile of apology. ‘Do you forgive me?’

‘There’s nothing to forgive, Charlotte.’

‘You must answer this summons. Will you ask Paul to help you?’

‘No, my love,’ he said, ‘I fancy that I can handle this on my own. Besides, my brother will be too preoccupied. With money in his purse, he can’t wait to spend it.’

The Theatre Royal in the Haymarket was packed to capacity that evening for a revival of Thomas Otway’s tragedy, Venice Preserv’d. It was given a spirited performance by an excellent cast but few of the men in the audience noticed the finer points of the verse drama or the striking set designs and costumes. Their attention was fixed on the sublime actress who played the part of Belvidera, the daughter of a Venetian senator, caught up in political machinations over which she has no control and who dies broken-hearted at the end of the play. In the leading role, Hannah Granville wrung every ounce of pathos out of it and reduced many of the female spectators to tears. The men were equally captivated but it was her melodic voice, her lithe body, her exquisite loveliness and, above all else, her extraordinary vivacity that aroused their interest

The thunderous applause that greeted the curtain call went on for an age. Male spectators unaccompanied by wives or mistresses flocked to the stage door, ready to offer Hannah all kinds of blandishments. Because she kept them waiting, the expectation built until it almost reached bursting point. Then she appeared. Framed in the doorway, she distributed a broad smile among her admirers and lapped up their praise while pretending not to hear their competing propositions.

A man’s voice suddenly rose above the hubbub.

‘Stand aside, gentlemen! Miss Granville wishes to depart.’

The crowd swung round in surprise to see an elegant figure standing behind them with his hat raised in greeting. Feeling deprived and disappointed, the suitors moved reluctantly aside so that Hannah could sweep past them and receive a kiss from the newcomer. There was a collective gasp of envy.

Paul Skillen enjoyed his moment to the full before giving a dismissive wave to the throng. Then he offered his arm to the actress and spirited her off into the night.

CHAPTER FIVE

‘Why didn’t we head straight for Plymouth?’ complained Moses Dagg.

‘That would’ve been dangerous.’

‘It’s so much closer, Tom.’

‘Yes, but it’s also the first place they’d have gone. Soldiers on horseback can move much faster than we can on foot. They’ll have warned all the ports to be on the lookout for us. That’s why we had to find somewhere else.’

‘I’m fed up with hiding for most of the time.’

‘Then you shouldn’t have been born with a black face,’ said O’Gara, jocularly. ‘It makes you stand out, Moses, so it’s better if we move at night. Unlike me, you can’t dive black into a pool and come out white.’ He gave a throaty chuckle. ‘After all those months cooped up, that swim we had was wonderful.’

Dagg nodded enthusiastically. ‘We haven’t had a treat like that for ages.’

‘It helped to wash off the prison stink.’

Making their escape from Devon proved more difficult than they’d imagined. Dartmoor had deliberately been built in a remote part of moorland. The soil and the climate were unsuitable for growing crops so no extensive agriculture had developed there. Ice cold in the winter, it was also enveloped in thick blankets of fog that bewildered anyone foolish enough to travel across the bare landscape. The fugitives had the advantage of warmer weather and clearer skies but so did the mounted patrols sent out after them. Much of their days had therefore been spent concealed in various hiding places. When their food ran out, they were careful to take very little from the occasional farm. Had they stolen large quantities, the theft would have been noticed and reported. Hunger would have given their location away to those engaged in the manhunt and O’Gara knew that, if recaptured, he could expect no quarter from Captain Shortland. A reunion with the governor had to be avoided at all costs.

‘When do we make our move, Tom?’ asked Dagg.

‘We’ll wait another hour or so until they’ll all have gone to bed.’

‘It’s dark enough now.’

‘I’m taking no chances.’

‘How long will it take us to get to London?’

‘That depends on the weather,’ said O’Gara. ‘We’ll hug the coast for safety.’

‘It’ll be good to be back at sea again.’

‘That’s where we belong, Moses.’

‘I’d hate to be locked up again. We were like caged animals.’

‘We’ll be safe in London. They’ll never find us there.’

They were crouched behind a hedge at the margin of a field. Having worked their way south-west, they’d found a hamlet on the coast. It was little more than a straggle of whitewashed cottages along a pebbled beach. Fewer than thirty souls lived there. When the fugitives first saw it in daylight, the sight of a couple of small boats lifted their spirits. If they could steal one, they could at last shake off the constant pursuit. While they bided their time, they took note of the tides and the jagged rocks they’d need to negotiate once afloat. A long, frustrating day had eventually yielded itself up to darkening shadows. The hamlet had gradually lost colour and definition.

Tom O’Gara was acting on instinct. When he felt that the time was ripe, he slapped his friend on the shoulder and they set off into the gloom. As they got closer to the shore, they found the aroma of the sea invigorating. A bracing wind tugged at their clothing. When it was harnessed, it could speed them away from the county. They crept warily past the little houses, reassured that no light showed in any of the windows. Reaching the boats, they dragged one of them slowly and carefully towards the water, thrilled when they felt the sea lapping at their ankles. They heaved on until the vessel began to float.

‘We’ve done it, Moses,’ said O’Gara, joyfully.

‘They’ll never catch us now.’

‘Goodbye, Captain Shortland, you murderous bastard.’

‘All aboard, Tom.’

With the boat now bobbing as each new wave rolled in, they climbed into it and felt the familiar sensation of the sea beneath them. They were just in time. Out of the darkness, a large, angry dog suddenly appeared, baring its teeth and barking furiously. Running into the water until the sand disappeared beneath its paws, it began to swim frantically towards them, as if intent on tearing them both apart. The animal gave them the impetus to hoist the sail at speed and catch the first full gust of wind. Before the dog could get within yards of it, the boat was being powered out to sea beyond its reach, as if pushed by a huge invisible hand. The last thing they heard were the plaintive howls of the dog and the outraged yells of the people who’d been roused by the barking and run out of their cottages to see what was happening. The shouting continued but the sailors ignored it. When the protests eventually faded away, they were replaced by the whistle of the wind, the flapping of the sail and the jib, the creak of the timber and the sound of the waves splashing against the hull.

They sailed on towards London.

Micah Yeomans handed over the money then raised his tankard in celebration.

‘We’ve got them,’ he said before taking a long swig of ale.

‘I’ll drink to that, Micah.’

Simon Medlow lifted his own tankard to his lips. The two men were seated in a quiet corner of the inn. They were beaming with pleasure.

‘The trap has been baited,’ said Medlow.

‘You did well.’

‘It was costly. I had to give a large deposit to Ackford. It was the only way to convince him that I was in earnest.’

‘You’ve had ample recompense, Simon. There’ll be more money when we finally catch the pair of them trespassing in Mayfair.’

‘They’ll argue that Hobday engaged them to look after the house but he’s a hundred miles away. When he gets back, he’ll depose that he’s never seen or heard of the Skillen brothers before.’

‘Meanwhile,’ said Yeomans, ‘the other Everett Hobday has gone back to being Simon Medlow and will have disappeared from sight altogether.’ He took another sip of ale. ‘I hope you asked for both of them.’

‘I did, Micah. You’ll nab Peter and Paul Skillen.’

‘I’ve waited ages to put salt on their tails.’

‘How many men will you bring?’

‘I’ll bring plenty,’ said Yeomans. ‘I know how slippery they can be.’

The Bow Street Runner was still sorely wounded by the way that the brothers had arrested Ned Greet and claimed the reward for his capture. Determined to strike back at them, he’d hatched a plot. Yeomans had been charged with the task of looking after Hobday’s property in Upper Brook Street while the man and his servants were away in the country. He’d arranged for an old acquaintance, Simon Medlow, to impersonate Hobday and lure the Skillen brothers to the house. At a given signal during the night, Yeomans and his men would let themselves into the property and arrest Peter and Paul for trespass and attempted burglary. Medlow had been the ideal person to employ. He was a confidence trickster who owed the Runner a favour because the latter had turned a blind eye to his activities in the past. Medlow was not the only criminal with whom Yeomans had a mutually beneficial arrangement. In return for immunity from arrest, a number of them paid him a regular fee. Those who refused to do so had enjoyed no such indulgence from him and his colleagues. They were hunted down relentlessly until they were caught.

‘Gully Ackford is a wily character,’ said Yeomans. ‘Only someone like you could have pulled the wool over his eyes.’

‘He’ll be implicated as well, of course.’

‘That’s the beauty of it. Ackford will have to appear in court and admit that he was taken in by the bogus Mr Hobday. It will be a humiliation for him. When word gets out that he and his detectives were so easily taken in, people will not be so keen to engage their services and the Runners will be cocks-of-the-walk again.’

‘It’s a clever ruse, Micah.’

Yeomans smirked. ‘I swore that I’d get my revenge.’

Esther Ricks was a short, dark-haired, roly-poly woman in a plain dress that failed to conceal her spreading contours. She lived in a small terraced house off Oxford Street. When he called there that morning, Peter Skillen put her age at around forty and could see that she must have been an attractive woman when younger and slimmer. As soon as she heard that he’d been asked to investigate the disappearance of her sister, she was so pathetically grateful that she clutched his arm.

‘Oh, do please find her, sir. Anne is very precious to me.’

‘I’m sure that she is, Mrs Ricks.’

‘We lost both of our parents and have no other family beyond each other. When Anne’s husband died, we pressed her to come and live with us but she’s very independent. She preferred to rent a room elsewhere. Anne said that she didn’t want to impose on us. The truth of it is that she’d have felt too confined here.’

‘Describe her for me,’ said Peter, easing her gently away.

Given the invitation, Esther seized it with both hands, talking lovingly and at length about her younger sister. What emerged was a portrait of a hard-working woman in her thirties, turned out by the landlord on the death of her husband and forced to fend for herself. Though the menial job at the Home Office did not pay well, it gave Anne Horner an enormous sense of pride to be working, albeit in a lowly capacity, for the government. Dedicated to her role, she had never missed a day or been anything other than thorough in her duties. To the outsider, hers might seem a strange and very limited existence but it was – her sister argued – the one she chose and liked.

‘That’s why it’s so unusual, Mr Skillen,’ she said. ‘Only something very serious could keep my sister away.’

‘You say that she was in excellent health.’