Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

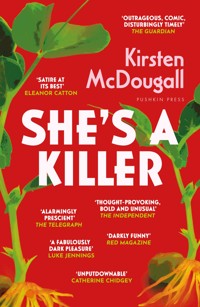

Alice is struggling to find things to care about. Branded 'smarter than most' at the age of seven, she now works in Enrolments at the local university and spends her time stalking the internet for shoes she can't afford. Meanwhile, the climate is in crisis and wealthy immigrants are flocking to New Zealand for shelter, stealing land, driving up food prices and taking over.When Alice meets teenage genius Erika, life suddenly gets a lot more interesting. But Erika soon reveals a dangerous plan to set things 'right', forcing Alice out of indifference and into action of the most radical kind. Just what is a slacker to do?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 535

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Kirsten McDougall is a novelist and short story writer. Her 2017 work Tess was longlisted for the Ockham NZ Book Awards and shortlisted for the Ngaio Marsh Award. She’s a Killer was longlisted for the 2023 Dublin Literary Award and Ockham NZ Book Awards 2022. Kirsten works in communications for a union and lives in Wellington, New Zealand.

SHE’S KILLER

Kirsten McDougall

Pushkin Vertigo

A Gallic Book

First published by Victoria University Press, New Zealand in 2021

Copyright © Kirsten McDougall 2021Kirsten McDougall has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

First published in Great Britain in 2023 byGallic Books, 12 Eccleston Street, London, SW1W 9LT

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-913547-65-3 Hardback

ISBN 978-1-913547-68-4 Trade Paperback

ISBN 978-1-805334-57-6 ebook

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by Gallic Books Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

when the inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate

—Carl Jung, Aion

Chapter One

The first thing Simp said to me when she came back was, Just look what you’ve done. I was getting ready for work, splashing my face, armpits and crotch with three inches of water in a grimy basin. There was nothing I could do about my single-person water allowance; it was all that came out of the taps in the morning. I could have cleaned the basin, but she knew me better. Even though I hadn’t seen her since we were seven years old, when we burned our childhood home to the ground, it felt as though she’d never left. Simp was executive of my heart; she was like my hand was a part of my body, like my legs could move without me even thinking about them. Simp just was. And now she was back, a ghost limb, reasserting itself.

I walked out of the bathroom and she followed. I did not ask her why she was here and she offered no comment on the mould spots above the abandoned shower or on the carpet that bubbled in waves on the landing outside the kitchen, creating a trip hazard for unwanted guests. Instead she pretended to look at the books on my shelf and review them, like she was the one who’d read them.

Ends badly this one, she said.

I didn’t ask which one she meant. I’m a fan of unhappy endings. They’re more honest.

At the dining table I decanted some of Amy’s sauerkraut into a smaller container. This was my daily lunch. I stared at the gap in my rotting kitchen counter where my sprout grew. The sprout, an unidentified plant, had terrified my ex, Nick, who had a tendency to see signs and symbols where I saw ordinary life. It was one of the reasons we didn’t stay together. Still, even I could see that at some point I would have to allow Alan in to fix the counter. Most likely I would ignore it for months and then I would die because we were in an apocalypse. It wasn’t like I ever cooked anyway, so I probably didn’t need a counter.

I went to my bedroom to put on makeup. I covered my face in foundation and drew a line around the outside of my eyes, making them appear larger, more cartoonish than they truly were. This was the world now, a living cartoon. I paid proper attention with the mascara, and Simp said nothing. We both acted like this was completely normal because in our own peculiar way it was.

And when I left the house she came with me. I couldn’t see her but I could feel her beside me, perceptible but faint, as if she wanted to make me doubt she was there. I waited at the bus stop, and when the bus came she got on too.

It was a good day because my favourite seat, first up the back, was free. I liked the raised perspective it gave me. I could look down on the other passengers. Even better, my sauerkraut created a small ring of stink around my seat. I had purposely left the lid loose so that no one would sit beside me.

A prematurely middle-aged guy wearing a badly tailored jacket and a backpack covered in political statements got on and sat down in front of us. He had long thin hair which he pulled back in a ponytail. It was the kind of hair that would look stringy no matter how clean it was. With hair like that he would never get a girlfriend.

Like you know how to get a boyfriend, said Simp.

I turned away from her and looked out the window. I didn’t care for a boyfriend, but I did know how to get laid.

Since the wealthugees had started pouring into the city more than a year earlier, I’d had a number of casual encounters with men, new arrivals to the end of the world. The problem with them was that they mostly wanted to talk about living in a new country and where they could get good coffee, and their trauma and which was the best gym to work out in. I didn’t want to hear their stories and I couldn’t help them. They’d paid for a nice bottle of wine and mistaken me for someone who listened. Their stories were all the same. Their countries were flooded, burning or in drought. They ran from civil wars and useless governments, and they all had the money to leave. I got fed up with them. I pointed out to one guy that he was lucky. He’d been able to come to New Zealand because his family could offer large amounts of money in return for residency; they could afford a small piece of land on which to build a house. He didn’t like that. He slapped my face and yelled at me, saying I didn’t understand what he’d lost. Then, to make it worse, he sat on the floor and cried and begged me to forgive him because he had PTSD. It took me ages to get him out of my house.

You’ve always attracted losers, said Simp.

I didn’t know why Simp was on the bus with me where she could get sat on and pushed around. She’d never left the house when we were kids.

You make the rules, said Simp. Anyway, no one will sit next to you if you hold your face like that.

Outside, the grey street was empty. Wind was blowing up clouds of dirt and pollen, making the bad and boring architecture of our city look worse.

Since the protests over the wealthugee situation a few months back there were fewer people on the street – ironic considering the population had increased by half a million in the last eighteen months. The violence of the protests had shocked everyone. Five wealthugees had been shot by people who said they had no right to be here. The police armed up. The fancy restaurants where wealthugees ate had security guards on the doors. Schools and government offices installed metal detectors. The prime minister said there would be zero tolerance for violence against wealthugees. People said they were scared to go out.

On every media platform online there were long threads with people arguing. They said this wasn’t the New Zealand they knew. They said it was a brave new world. They said the government had not governed well in allowing large numbers of wealthy people from falling-apart countries to buy their way into our country. They said to turn them away would be immoral. They said that only allowing the rich ones to come was immoral. They said Turn the wops out their not wanted. They said our country was being colonised again. They said tino rangatiratanga. They said shut down the trolls, now is the time for empathy. They said tax the invaders! I stopped following. The threads pooled in a knotty tangle.

What I did was I caught the bus to work. I sat at my desk and ate the sauerkraut that my best friend Amy made for gut health. I turned on my computer and pretended to work. I read long-form articles with a filter that blocked stories containing the words catastrophe, terror, counter-terror, collapse, chaos, end of, deoxygenated, gelatinous, future. I was not interested in such words.

Avoidance tactics, said Simp, will kill you in the end. But you’ve always been good at denial.

I rolled my eyes and got my stuff ready to get off the bus, because my stop was coming up. I used to think it was uncool to signal you were getting off too early – like showing the other passengers your transition anxiety. And now I thought it showed how mature I was that I no longer thought that.

You’re so basic, said Simp. The world is falling apart and all you can think about is your personal psychology.

‘Fuck you!’ I said under my breath. I knew better than to talk normally to an imaginary friend on a bus.

The bus came to stop, and I stood, knocking the sauerkraut out of my bag onto the sad guy in front of me.

I moved down the aisle quickly but I could hear him yelling behind me. He was swearing and saying, ‘What the hell is that?’

I turned, and Simp was at my ear, saying, Now look what you’ve done!

As I tagged off I looked back. The guy was causing a terrible racket and shouting about vomit on his coat. His stringy ponytail was swinging over his right shoulder like a limp rat’s tail while he flicked sauerkraut off his left shoulder with his bare hands. Passengers around him were leaning away from the stuff that was flying through the air. He looked terrible, worse than he had before.

I got off the bus.

You tipped your sauerkraut on his shoulders, said Simp.

‘It was an accident,’ I said as we walked along.

You’re a dingo picking on the weakest wombat, she said.

There were a few more people around now, serious-faced and hurrying to their work, paying no attention to me. We stood at an intersection, waiting for the lights to let us cross.

‘We’re not in Australia,’ I said.

In the gutter, a pigeon was strutting around picking at white crumbs. It was not concerned about the end of the world. What would it be like to be a pigeon thinking only of the next crumb? It occurred to me that I was more a pigeon than a dingo.

Maybe, said Simp. Playing on the road where it will easily get hit by a car or a bus – and that crumb’s not food. It’s polystyrene.

The light went green. We started crossing the road and the pigeon flew away.

Uh-oh, said Simp. Now you’ve really done it.

Coming towards us was bad-hair guy. He looked very angry and was moving quickly, eyeballing me as he got closer. He must have got off at the next stop and doubled round to find us.

‘You,’ he said, sticking his finger out at me as he reached us. ‘What did you tip out on my jacket? What is this shit? Some sort of bomb?’

I looked at his shoulders. Unfortunately it was from when Amy was going through her turmeric phase. She even put it in her sourdough.

You could just apologise and move on, said Simp.

‘It’s not a bomb,’ I said to the guy. ‘It’s fermented cabbage. If it was a bomb it would have exploded.’

‘What?!’ he said. ‘You tipped weird shit on me and you didn’t even stop to apologise? In this environment? I could call the cops on you.’

The guy’s nose was twitching. Maybe he had a nervous tic. I looked at the stains. There was no way he was going to get that turmeric out of whatever the cheap fabric was he was wearing. I almost felt sorry for him.

I looked down at my bag and forced a surprised expression onto my face.

‘Oh my god!’ I said. ‘My sauerkraut! It must have fallen out when I tripped. You know, bus drivers never stop smoothly.’

His nose was wriggling all over his face. ‘You just got off that bus,’ he said.

‘It was my stop,’ I said. ‘And it’s just my mother … she’s ill.’

I rubbed my eye with my swear finger like it was itchy or I was about to cry. I screwed my face into an approximation of sadness.

Did you just call it the swear finger? said Simp.

‘Oh,’ said the guy.

His hair was not only long and thin, it was oily with small pieces of dull bald scalp.

‘I’m not making excuses,’ I said. ‘But I didn’t notice what had happened because of … her cancer.’

The guy looked sympathetic. ‘Your mother’s got cancer?’

I nodded.

‘Oh, that’s awful,’ he said. His stained shoulders dropped a little.

I put my hand back in my pocket. The finger’s only good if it’s subtle.

‘She’s having treatment,’ I said.

Simp snorted.

‘My wife had breast cancer last year, she’s in remission now,’ he said, looking down.

‘You have a wife?’ I sounded surprised because I was.

‘Yes?’ he said, his face screwing up a little.

‘Good,’ I said. ‘I mean, that’s … Good for you.’

He looked away down the street a moment. A truck went past, spewing fumes behind it. He started nodding his head frantically.

‘What’s that supposed to mean? Good for me? I know what you think! You think because I have alopecia and facial tics that no one will love me … But yeah, I have a wife, and we’re happy, and I don’t go throwing my lunch over people on the bus. I could have you up for assault, you know!’ His voice had risen to shouting now and a few people were starting to look at us as they passed.

He’s going to have a seizure, said Simp.

The guy had beads of sweat on his forehead, and his left eye kept winking open and shut, open and shut. I couldn’t say sorry, especially not now I knew he had a wife. Dropping sauerkraut on someone was not assault.

‘I’m running late for work,’ I said.

‘Fuck you,’ said the guy. ‘You’re what’s wrong with the world! Full of hate and anger!’ He glared at me, his nose and cheeks twitching like mad, then he turned and strode away.

Some people, said Simp, looking straight at me.

I turned on her and I didn’t care who saw. ‘This is your fault!’ I shouted.

Uh-uh. I got no hands, she said. How could it be?

I breathed in and out. I would have slapped her if she was real.

‘Go back to where you came from!’

The thing is, said Simp. You’re angry cos you’ve lost it. Your youth, your fiancé, your smarts. I mean, can you even calculate the square root of 762 anymore?

‘You’re not even real!’ I screamed.

I knew that I was screaming and that people were taking a wide berth, staring at me as they passed.

Okay, an easy one, she said. If a ship had twenty-six goats and ten sheep on board, how old is the ship’s captain?

‘What is it you want from me?’ I shouted at her shadowless body.

My heart is yours, as is my heart’s desire, she said.

I felt a fire in me. It was coming from me and it was burning me at the same time. I shouted at her. ‘That’s a critical-thinking question, not a maths question, and 762 is an irrational number!’

I screamed at my imaginary friend returned from the dead. But I was shouting at nothing. Simp had gone.

I stared back at those people who were unashamed to watch a woman lose her shit on the street early on a Wednesday morning here at the end of the world. I wasn’t afraid of them. I eyeballed every one of them and even the most stubborn began to bow their heads and move on. Most people don’t like scenes. Most people are cowards.

The hill I climbed to go to work every day stood before me. Already I was running late, so I took my sweet time. There had been a moment on the bus when I’d made a decision to tip my lunch out, but I couldn’t isolate it. I knew why I’d done it. Simp was right about some things. I could be a bully and my avoidance tactics were second to none and perhaps I’d wasted my natural talents and for sure my flat was a dump. But I had no heart’s desire. Not anymore. I’d trained that out of me.

Chapter Two

Once I got through university security I was twenty minutes late and there was a mature student already waiting by my cubicle. You only had to be twenty-five to be considered a mature student. Lots of people complained about it – how it made them sound elderly when they were mid-twenties. This guy looked like he was in his thirties. He looked like he had money and he also looked grumpy.

I hung my jacket on the back of the chair and sat down.

‘You’re late,’ he said, pointing at the opening hours notice on the wall.

‘Hello,’ I said.

‘Enrolments?’

‘Eh?’

‘Are you or are you not Enrolments?’

He spoke in a matter-of-fact way and had an English-sounding accent, though he looked Asian. Definitely a wealthugee. We’d been primed to watch for them. They were worth a lot to the university. It was core policy to be very welcoming to them.

‘Sure,’ I said, putting a big smile on my face.

‘I have come to make a formal complaint,’ he said.

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘You should probably see Gerald for that. He’s my manager. He deals with all the complaints. He’s trained in helping people with their complaints.’

‘No, it’s okay,’ said the guy. ‘I can talk to you.’

I tried hard to smile.

‘You will need to record this because it’s formal,’ he said.

I grabbed a piece of paper and wrote the date at the top, then wrote Formal Complaint and underlined it. I looked up at him. ‘Okay, I’m ready,’ I said.

‘Don’t you use a system?’

I held up my pen. ‘This is a system,’ I said. ‘Computer’s not ready yet.’ I tapped a few keys on my computer to show I was making an effort.

The guy shook his head like he didn’t believe me, even though it was true. I hadn’t had time to turn my computer on.

‘Okay.’ He wriggled his finger in the air as he spoke. ‘I want to know why there is no Russian Literature Department in this university.’

That wasn’t the sort of complaint I’d been expecting. Generally people came here to complain about the number of forms we made them fill out. There hadn’t been a Russian Literature Department in the university since the nineties. I told the guy this.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘It’s completely unacceptable.’

‘Maybe,’ I said, ‘but I don’t know if you can retroactively lay a complaint about something that stopped happening nearly thirty years ago. I mean, isn’t that like complaining to Germany about World War Two? They’re just gonna nod their heads and say, We know, we know, it’s such a shame.’

I wasn’t, strictly speaking, giving my best customer service, but I was feeling distracted by the sauerkraut incident. I’d done it because Simp was there and she was pissing me off. I’d done it to prove I still had my edge.

‘It’s nothing like that,’ said the guy. ‘That is a specious argument.’

I wrote ‘no Russian literature’ and ‘specious argument’ down on my piece of paper so he knew I was taking him seriously. I looked at him and nodded. I tried to look like I was making an effort. We were supposed to take all enquiries very seriously, most especially wealthugee enquiries. It was part of cascading educational dreams into reality. Enquiries into fee-paying students.

He tapped his finger on my desk. ‘Though maybe you have a point. This is an ethical issue. I’m asking that a university actually act like an institution of higher learning and allow its students to study different world literatures. In fact, your government should mandate that the literatures of the world be taught in its universities.’

‘I don’t know if our government can mandate—’

The guy interrupted me and continued his rant. ‘Especially now you’ve got people from all over the world living here who don’t want to just study English novels. We want to read big novels, ones with ideas. World-saving novels!’

I wanted to say that I thought some English novels had ideas in them too, but I held my tongue. This guy was definitely an idealist, and since living with Nick I knew better than to argue with them. I knew that there were guys who made proclamations about Russian literature because they thought it made them more attractive. Anyway, I kind of agreed that the university should have a Russian Literature Department, if only to show they weren’t all about commerce. But most students didn’t care about any of this. They just wanted the answer to the exam question so they could get a decent grade for a degree that would put them in debt for many, many years.

I shrugged and nodded.

‘What?’ He shrugged and nodded, copying me, but without sarcasm, which I expected was a thing people did in the place he was from. I’d noticed that wealthugees didn’t approach confrontation with the same level of passive aggression as New Zealanders, but I didn’t know if the lack of passive aggression was a wealth thing or a foreign thing.

I wondered if Simp had made it home okay, which was a pointless thing to wonder about. It would be better if she just got hit by a bus.

‘I need a coffee,’ I said. ‘I really need a coffee.’

I didn’t mean to say it out loud, but I wanted to get away from this guy’s complaint. Simp coming on the bus this morning had done me in. The fact that the university didn’t teach Russian literature didn’t matter, not anymore.

He looked at his watch and sighed. ‘I’ll come and get one with you,’ he said. ‘I really need a coffee too.’

I didn’t know what it was with the morning but I seemed to be attracting annoying men. I opened my mouth to squash the idea of coffee together.

‘I’ve just moved here,’ he said, a tad too quickly. ‘So the coffee is on me.’ He smiled at me in a generically friendly way.

‘Whatever,’ I said. I didn’t have to sit down with him and I couldn’t really afford to buy my coffee every day, so I would take it as a gift and get out.

We started walking towards the café.

‘Are you from here?’ said the wealthugee, like he was trying to make conversation.

‘Ah – yep,’ I said.

‘It’s nice,’ he said.

The dude was just saying words out his mouth now. This city was windy and grey. Its buildings were ugly and boring. Sure, we had trees and the harbour. But the harbour had poo leaking into it and you couldn’t swim there even on the two days a year when it was warm enough. I wasn’t sure if we were still in a customer-service relationship given that he’d just invited himself for coffee with me, so I nodded. I knew if I didn’t sign this wealthugee up to a course, even if it was one that didn’t exist, questions would be asked.

‘I’ve been moving between London and Hong Kong for the last eight years,’ he said. ‘So it’s nice to come somewhere smaller.’

‘Oh! I wondered if you were a little bit Russian,’ I said.

He gave me a funny look. ‘Because of my preference for Russian literature?’

‘Aha.’

‘I just like the big novels.’

I looked down as we joined the end of a very long queue. I noticed his shoes. Limited-edition Nikes. They cost around US$800. I surfed the sites that sold them. How rich did that make him? Rich enough for my fantasy shoes.

All around us students were looking at their phones, flicking between apps, searching for something that might turn their morning around. I estimated I had at least another ten minutes of conversation before I would get my free coffee. But I also knew there was more to be got.

‘So what were you doing in London and Hong Kong?’ I said.

‘Investment banking, drinking in fancy bars, working out at the gym, looking after my kid.’

All of this confirmed he was a wealthugee.

‘You have a kid?’ I said.

‘Yes. You sound surprised.’

‘It’s just, how old are you?’

‘Forty-seven.’

‘What?’

He nodded.

‘I thought you were thirty-something.’

‘It’s my skin. Asians age slower than white people. I’m half Chinese and I got my best-looking bits from my mother.’

‘That’s a bit of a generalisation, isn’t it?’

‘My mother was attractive.’

I rolled my eyes at him. It was evident he needed more eyeroll in his life. ‘Asians age slower than Europeans?’ I waited for him to say something, to justify what he’d said. He looked at me. Like he really stared, and then he cracked up.

‘What?’ I said. ‘What’s so funny?’

I had to wait for him to stop laughing. A few people glanced at us.

‘You think I’m making race-based assumptions, don’t you?’

‘No,’ I said. I sounded slightly sulky.

‘I didn’t say you looked old,’ he said.

I looked at his blazer and decided he was definitely quite rich. He held himself upright like he knew his worth. The blazer was made from a fine fabric and it hung perfectly on his frame. I wanted to touch it, to know its weight and texture.

‘That’s a nice blazer,’ I said.

‘Thanks.’

He was slightly taller than me, but I wondered if that was the shoes.

‘How old’s your kid?’

‘Fifteen.’

‘Okay, well … I guess you do have good genes,’ I said. ‘You don’t look like someone with a fifteen-year-old.’

‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘This queue is going on forever.’

‘Yeah, it’s slow here.’

‘Why do people come here if it’s this slow?’

‘I don’t know. Force of habit. The coffee’s good.’

‘In Hong Kong we’d be sitting down by now. And in London we’d be suppressing our complaints about the queue while looking extremely displeased.’

He looked at me, and I smiled apologetically as if I were the one slowing the service down.

I didn’t know what to say, so I pretended like I might choose something to eat. The cabinet was stuffed full of expensive food – pastries and salads made from grains I’d never tried. The cost of everything in the cabinet had gone up by at least ten dollars because of the wealthugees and various eco-political food events I didn’t follow anymore. I didn’t know how anyone who wasn’t a wealthugee afforded any of the food they sold here.

‘So why do you want to study Russian literature?’ I said.

‘Have you ever been to China?’

‘No.’

‘Well, if you’ve spent any time in China you’d understand. Young Chinese, they’re just like these people – tap tap tap on the phone, taking selfies with beauty filters, buying labels. Chinese are practical, you know? They just want to be able to eat good food, have some free time like anyone. But it’s a self-contained culture and even though shit has gotten real there, as it has in many places, people still act like things will stay as they are. Not everyone but a lot. That’s why I want to study Russian literature. I want to understand what it is we’re scared of. At a deep level.’

He was looking straight at me the whole time he spoke. It was too much, and I looked over his shoulder at all the young people moving lethargically about their business.

‘And Russian literature will help you understand Chinese fear?’ I said.

‘Not just Chinese fear. Human fear. And let me put it this way. You live on an island. You don’t have a border to patrol.’

Russian-literature guy’s face was serious. He had a tiny line between his eyebrows and it made him look a tiny bit sexy. There had been a time when I studied fear. I shook my head.

‘I mean, I know you have your own problems here,’ he said. ‘This is a colonised country after all. And now you’ve got a bunch of rich people buying their way in. A different type of invasion.’

‘Is China going to be invaded?’ I said.

He shrugged. ‘Maybe it will collapse internally.’

I frowned at him. He may as well have been speaking Russian.

We were now next in line to order. The young man in front of us was asking for a complicated coffee. He looked fit, like someone who really cared about taking good care of their body and money and eating well so he could live forever. He ordered coffee with almond milk. Russian-literature guy looked visibly annoyed at how long the young man was taking. He was talking to the café woman; they were flirting and laughing. Whatever they were doing, the café woman was being helpful and nice, way more helpful and nice than she ever was with me. I bought coffee here regularly even though I couldn’t afford to, and she never remembered my name. It really peeved me.

Finally I ordered and, once again, the woman asked me my name.

‘Almond milk,’ said Russian-lit guy, shaking his head at me and the woman behind the counter. ‘We all know how much water it takes to process almonds. Not to mention bees.’

He spoke in a calm tone, but it was an aggressive thing to say. It wasn’t her fault people ordered almond milk in their coffee, but I was pleased he was poking her because she was rude for not remembering my name.

‘Cows pollute the water,’ she said, matter-of-factly.

‘What other milk have you got?’ he said.

‘Breast?’ I said.

‘Oat and coconut,’ she said in a curt tone, giving me a very bad customer service look.

‘I was joking,’ I said.

‘I’ll have coconut milk.’ Russian-lit guy turned to me. ‘Do you want something to eat?’

I shook my head.

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘We’ll take two croissants.’

I looked away from him. Why would he order two croissants when I wanted none? That was alpha shit. We moved to the side of the counter to wait.

‘I saw you looking at the food,’ he said. ‘You don’t have to eat it if you don’t want to.’

A strange feeling came over me. I didn’t want the croissant. This guy was strange and egotistical, but then he also seemed far more straightforward than most of the people I dealt with all day – young people who didn’t know what they wanted or wanted to do even though they were putting themselves in massive amounts of debt. We all knew that in a few years none of it would matter anyway, but we had to pretend like it did, we had to go on. This guy with his irrelevant Russian literature query and his fine blazer had something loose in him. I hoped it was money. He excited me.

‘Can I ask you something?’ I said, looking at him with my most clear eye.

‘Sure.’ He returned the gaze.

‘Is there something forgettable about me?’

‘How do you mean? Because we only just met.’

‘That woman taking our orders, she never remembers my name even though I buy coffee here most days of the week. And it just makes me wonder, is there something about my face or the way my voice sounds that makes people forget me?’

He looked at me. I tried to stand still and not pull a face, even though I felt uncomfortable and aroused being looked at so closely. His eyes were tracing me – my jawline, my nose, eyebrows, all my freckles, the fresh pimple on my forehead, the scar I had under my nose from when Simp made me fall down the stairs outside our house when I was three. My earliest conscious memory of pain. My mother screaming at all the blood. He would see that.

My cheeks felt hot from all the attention. What I realised was that no one had looked at me like this for a long time.

He didn’t speak and neither did I. His eyes were dark brown, and the left one had some small lighter specks in it which you wouldn’t notice if you weren’t looking at him so closely. He was, I decided as he inspected me, quite good-looking once you got past his slightly snooty veneer.

‘Hmm,’ he said after a while. ‘It’s hard to tell.’

I huffed at him. ‘To tell what?’

‘It’s just that Westerners kind of look the same to me,’ he said.

My cheeks bloomed with heat again. I looked down at my feet, unable now to meet his eye. Then he laughed loudly.

‘Joking!’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t forget your face.’

His eyes were soft and he was looking at me with what felt like fondness.

Our coffee order was called. It was a relief to move away from him.

I handed him his cup and he thanked me.

‘I should get back to my desk,’ I said.

‘I’ll walk you back,’ he said.

We walked in silence past all the students chatting and tapping their phones. They wore ripped jeans and expensive T-shirts, long skirts like women from a religious order save for the crop tops which showed their tattooed bellies. Their faces were unlined, freshly pimpled, covered in foundation and black pen flicks on the eyes. They projected indifference but their true hearts were earnest. I’d read that they were the most anxious generation the world had produced. I was invisible to them now, but I remembered what it was to be nineteen or twenty-one and have no idea what was going on and to not appreciate that this was the best-looking I would ever be. They probably felt like they were going to die young – and they would, considering how things were going. They had nothing to look forward to, and all that was going to happen to them was they would get older and living would get harder. Our country already had one of the highest youth suicide rates in the world. I didn’t blame them. I hated looking older. Now that I was closing in on forty, I could totally see how my face would be moulded into the accumulated experiences of the years I’d lived. There was nothing nice about it.

‘Hey,’ said the guy.

He put his hand on my arm and we both stopped walking. It was the first time a man had touched me in months. I generally didn’t like people touching me, but this felt different. I looked down at his hand and he pulled away.

‘I’m Pablo,’ he said.

I held out my hand, not because I wanted to shake hands but because I wanted him to touch me again. His palm was warm and moisturised. Maybe it was always like that. I wanted to rub it like a piece of velvet.

Before we parted Pablo gave me his number. He said he’d like to take me out for dinner and, if I wanted that too, I could text him. He didn’t ask me for my contact.

‘I’ll see,’ I said, but I knew I would text him. ‘I’ll see’ always means yes.

That afternoon I had a scheduling meeting with Gerald, Brian and Kaylee. Kaylee was new to Enrolments, and Brian had been tasked with training her. Already I could see that Kaylee could not be trained, because she knew she was better than us. She was destined for higher admin spheres than Enrolments.

I’d seen people like her in the fifteen years I’d been here. They dressed in generic corporate wear and were hungry to organise and to be on top of all things at all times, as well as ahead of everything and sometimes behind some new things. I didn’t understand them, the Kaylees of this world. They were not stupid, and it was impossible they would not find what we did repetitive and boring. The work we did was a by-product of business systems that would use up people on the factory line until the robots could do it. We were the bowels of the university corporation, modern shovellers of figurative shit. I knew it wasn’t as bad as working directly with raw sewage, but it was meaningless and definitely less useful than actual shit shovelling. I found it fascinating that the Kaylees could stay so driven knowing all this. Even if their sights were set on realms beyond ours, with greater pay rates, they would still be raking muck. Outwardly, I remained sublimely neutral. I offered no additional help beyond that which was asked for, nor any impediment.

‘So,’ said Gerald. ‘How are we all feeling?’

Gerald had recently attended a professional development workshop which led him to attend to our feelings first when opening a meeting. This would eventually fade out and morph into a different routine when he went to the next workshop. For now we were stuck with Gerald’s version of Culturally and Emotionally Intelligent Leadership, as well as with the potted ferns he’d bought for our work desks to remind us of our connection with nature which was more important than ever in our time.

When I’d asked Gerald to elucidate how a plant in a plastic pot signified more than desktop decoration, he’d not sighed as he usually would but said, ‘Good! I like that you’re asking questions!’ Which was presumably part of his new leadership style. But he’d offered no satisfactory answer, because there wasn’t one.

‘I’m quite tired,’ said Brian, in answer to Gerald’s question.

‘What was that, Brian?’ said Gerald. He was shuffling through the schedule for the upcoming open day.

‘You asked how we were feeling, and I said, I’m quite tired,’ said Brian.

‘Oh,’ said Gerald. ‘I’m sorry to hear that, Brian.’

‘Have a coffee,’ said Kaylee, who was solutions-focused, with little time for Brian’s physical sensitivities.

‘I can’t drink coffee after midday,’ said Brian.

‘Sensible,’ said Gerald. ‘For good sleep hygiene.’

‘I can sleep,’ said Kaylee.

‘Good for you,’ said Brian.

I said nothing. I liked to see how little I could contribute in these meetings. My all-time Personal Best was three words, nothing to add, of which I had been inordinately pleased at the time. I would have liked to poke Brian with further questions about his fatigue, such as, How are your iron levels? Are you getting adequate exercise? Is your sleep disturbed by a creeping sense of abject horror at the meaninglessness of your day-to-day routine and the advancing apocalypse? But I’d already had a warning from Gerald about my attitude in relation to team morale, and while I wasn’t above pushing team morale in interesting directions I was keen to see if I could beat my PB.

‘Fantastic,’ said Gerald. ‘Right! Task Windows?’

Kaylee, Brian and I handed over printouts of our completed, current and to-do Task Windows.

‘Brilliant, thanks, people. Now to the open day schedule.’

‘Ah, Gerald?’ said Kaylee. ‘I wondered if I might make a suggestion about Task Windows before we moved to open day?’

‘Of course, Kaylee,’ said Gerald. He opened his eyes really wide like he was interested in what she had to say.

‘I’ve identified a potential initiative which would organise Task Window data automatically into priority categories. At present it’s organised manually in part?’

Kaylee put question marks at the end of statements as a way of sounding open-minded.

‘That’s correct,’ said Gerald. ‘I’ll warn you, any new initiatives need to be a zero costing, as we’ve had the word that budgets must remain static or reduce for the next year.’

‘This won’t cost anything,’ said Kaylee, her mouth curved up like she was smiling.

‘Good, good. Let’s hear it then,’ said Gerald.

‘Great.’ Kaylee cleared her throat and stood up like she was about to give a TED talk.

‘Currently Task Manager organises workflow by date stamp? And while it’s helpful to know when an enquiry came in, this does not reflect the reality of how we work because we all tend to prioritise enquiries depending on the urgency we perceive the enquiry demands? Effectively we override the Task Manager system and …’

While Kaylee talked I thought about Pablo’s hands. The skin on them was very smooth, like the skin on his face and neck, and I wondered if he exfoliated his whole body. Just thinking about his hands I felt turned on, which was interesting because not many things turned me on these days. Kaylee’s voice became a static background noise while I let myself dream of Pablo putting his soft, moisturised hand on my bare arm, running it up to my shoulder and over my throat. Then he’d start to run it down my body. I could feel myself growing wet just thinking about it. I definitely would text him. Tonight? Was that too soon? I’d need to search the correct amount of time before you should text a person who gives you their number but doesn’t ask for yours.

The room had gone quiet. Kaylee had stopped speaking.

Brian said yes and Gerald looked at me and I nodded. I didn’t count nodding as words, so I was still on target with my PB.

‘All agreed then,’ said Gerald. ‘Kaylee, if you could send that to me as a memo I could organise it as a work structure and send it out to the team.’

‘Written up already,’ said Kaylee. ‘I’ll send the memo when the meeting concludes?’

‘Goodness,’ said Gerald. ‘Very efficient. Right, to open day. I thought we’d try something a little different this year.’

Kaylee beamed like this was the best news she’d heard all day. Brian was checking his GreenTrade account on his phone. He was always selling things, mostly stuff he’d bought a month ago on GreenTrade. Last year I’d asked him if he made any money from doing this, and he’d told me that wasn’t really the point. What was the point? I’d asked. It’s the ebb and flow of the game. Satisfying the customer, he’d told me. So you lose money? I said. Not everything is about profit and loss, he said. What sort of person loses money selling pot? I said. That’s not all I sell. I also sell stuff to help people grow their own, he said. You’re a riddle, I said. Because I don’t conform to your capitalist framework? said Brian. Buying and selling is one of the keystone activities of capitalism, I said. I’m not just trading, I’m making a community, he said. I take it people give you money for their dope? I said. Brian was quiet a moment. I give a lot of stuff away, if they’re really sick or in pain, he said. Also, I’m stockpiling gardening equipment. I nodded and left it at that. I didn’t want to know about Brian’s stockpiling. But I had a certain understanding of it. My mother had hoarder tendencies.

Five years ago I’d hired a container and I’d helped her get rid of stuff. It was the worst thing we’d done together in our lives. She became impossible, refusing to let me throw out empty chocolate boxes she’d collected on our trip to Europe when I was twenty-six. In the end I told her that if she didn’t let me get rid of some of the piles I would burn the house down, and she knew I was perfectly capable of such an activity. Afterwards she sulked for a month and I could do nothing to pull her out of it. I had failed to comprehend the deep attachment she had to her stuff. Unwittingly I had walked into the museum of her soul, stocked with the displays of her lifetime, and had not recognised it as such. I was her daughter but that didn’t mean I understood any of this, or any of her. My mother, on the other hand, believed that she understood me fully. That was the start of when we stopped speaking so much.

‘Which will give us a competitive edge over the other university,’ Gerald said. The other university was like the Scottish play for Gerald – we were never to use its name. He tapped the table with his finger. ‘Brian, are you listening?’

Brian looked up. He had not, in fact, been listening. Neither had I, but I had my attentive face down pat. I was capable of astral travel while looking like I was entirely present. Brian found it harder to dissemble. I could have quietly suggested that he practise his work-meeting face had I had sufficient empathy for him.

‘Sorry,’ said Brian. His phone was still in his hand under the table and anyone could see it was killing him not to look down at it.

‘I know that you all understand the importance of open day,’ said Gerald in his most patient voice. ‘Not just to us in Enrolments but to the future of the university, now more than ever given the … the …’ Gerald couldn’t say the words ‘climate apocalypse’ because he had a new baby.

Brian’s right eye started twitching with the effort of not looking at his phone.

Gerald was deluded. He’d get grand when he wanted to make a point, because he still thought that getting us to work was a matter of motivating us. He couldn’t comprehend that Brian and I were beyond his motivational reach when it came to work. Kaylee too, but that was because she had her own thing going on.

‘I’m right with you, Gerald,’ said Brian, his right eye blinking madly.

‘Have you got something in your eye?’ said Gerald.

‘Yes!’ said Brian, relieved that he finally had an excuse to leave the room and check his trade. He stood up, holding his right hand over the eye, his phone in his left. ‘Year-round hay fever,’ he said. ‘I’ll just go and flush it out.’ When he got to the door he already had both hands on his phone, updating furiously. ‘Back soon!’

Kaylee shook her head. ‘I think we’ve been through everything we need to now anyway, Gerald?’

Gerald looked tired. I never asked anything about his life outside of work, but I knew more than I wanted to because he told us. He had a two-year-old and a new baby who woke every night at 1:50am with colic and cried until 6am, when Gerald got up to get the two-year-old breakfast. He was putting on weight because he ate six Weet-Bix at dawn, then was starving by mid-morning so would buy himself a pastry and two coffees which he couldn’t afford on his entry-level manager salary. It was a bad habit. Kaylee pretended to be interested in Gerald’s news but would quickly move the conversation on. I didn’t say, Serves you right for producing more people, but it was what I thought.

Kaylee stood up and left the room. As I was following her out, Gerald caught my arm.

‘A word?’ he said.

A feeling of panic ran through me. A one-on-one conversation was going to make it hard to achieve a new PB.

He waited until Kaylee was out of earshot and then he said, ‘I just wanted to check in with you. You’ve been very quiet recently.’

I didn’t say anything and waited for him to fill the space, which I knew he would.

‘It’s just I wanted to make sure everything was okay.’

I nodded.

‘And you’re all on board with our new approach to open day?’

I nodded again but with more enthusiasm to indicate I was completely on board. I could have stepped out the door and turned to talk to him. If I was outside the threshold of the meeting room I would technically be allowed to talk, but that felt like cheating so I hung on.

‘Good. I might be misreading you. I’m so tired at the moment. The baby …’ He looked away from me, reached over and pushed the door shut. ‘I know you’re not interested in that stuff, and really why would you be?’ His tone had a slight self-pitying quality which made me despise him.

‘I miss you,’ he said.

I looked up at him, surprised. He almost never referred to our scattered and brief sexual acts, and neither did I. We both pretended they never happened. So why was he referring to them now?

‘I do care about you,’ he said. ‘Even though I’m distracted by my tiredness and workload I just wonder if you’re happy? You are the smartest person in our team, probably the smartest out of all the professional staff in this university, and yet you stay here when you could do so much more.’

I gave up on my PB for this meeting. I could see it was going to be impossible and anyway I could count this as an exception because it was.

‘I’m as happy as a clam,’ I said. I said it to make him understand that he didn’t make me happy. Were clams happy? Mostly they were extinct.

‘Don’t you want more, you know, to do more?’ he said. Gerald always tried. That was his problem.

‘Don’t you want more?’ I said.

He reached out and brushed my arm. ‘Sometimes I find it unbearable working around you.’

I gently pulled away from him. I didn’t want him to touch me. ‘You’re tired. Probably delusional.’

How could he find it unbearable to be around me when I didn’t say a word? I wanted to shout at him, These are random sexual urges! Nothing to do with me! But I could see desire in his tired eyes and I knew that he would do exactly what I told him to do. Part of me agreeing to our casual sex acts was that I liked getting Gerald to do things for me, not that I actually liked him. The power imbalance was like sniffing petrol fumes – bad but so good. If I wanted him to lick the table he would. He would have one finger in my cunt and I could press his face into the meeting table as hard as I liked and tell him to lick it and he would absolutely do the best job of licking the table clean.

But right now I was tired of listening to him and of filling out stupid Task Windows. I was pissed off he’d ruined my attempt at zero talking just as I’d almost met my new PB. Although at least it gave me time to think about what came next. Because, after I had met it, what came next? Negative talking? Or maybe it was how many meetings in a row I could say nothing?

I moved up close to Gerald’s face. He was reasonably handsome but his breath was often stale.

‘I tell you what,’ I said.

He was caught in his desire and fatigue – his eyes were glassy, pupils dilated.

‘Sit down on that chair,’ I said.

He did as I told him, didn’t even say, But we’re at work, like he used to. He really was in a bad way.

‘Put your head on the table,’ I said.

He did.

‘Shut your eyes,’ I said.

He did.

I walked up to him and stroked his neck. He gave a little moan. He was so pathetic. I leaned down and whispered in his ear.

‘I’m going to leave you here for twenty minutes.’

‘Okay,’ he said.

‘Shut up!’

‘Okay.’

‘You’re to go to sleep.’

Gerald started to protest, so I reached down to the inside of his thigh just below his groin and pinched a tiny piece of skin as hard as I could.

‘Ow! That hurt!’

‘Shut up and do as you’re fucking told!’

‘Okay,’ he said.

I went back to my desk and did a search for how long you should wait before you text someone who gave you their number. The general advice was that you shouldn’t do it straight away because that could come across as over-eager, but nor was there any prescribed time for how long you should wait. Texting this afternoon wouldn’t be advised, I decided. Then I decided I would wait until that night as a test of my impulse control, which had failed this morning when I’d tipped sauerkraut on the bus guy’s cheap jacket.

I settled in to read an old long article about how two companies that made and controlled a large portion of the market for glasses frames and lenses had amalgamated into one company. The article explained how the father of the frame company was a complete megalomaniac who wanted to be the only producer of the world’s spectacles, and this was entirely within his means because of the amalgamation and because more people than ever were going myopic due to the time they spent indoors and at screens. They called it an epidemic of myopia. It was the sort of article I loved to read at work – long and dramatic, mostly well researched and irrelevant to the most pressing problems of the world or my life. Perfect.

An hour later Kaylee came by my desk and asked me if I’d seen Gerald.

‘No,’ I said.

I’d forgotten about him.

When I went through to check on him he was snoring, his head still where I’d told him to leave it on the meeting-room table. He was made to be eaten by lions.

Chapter Three

There was no more I could do for Gerald, so although it was only 4pm I decided to leave work and visit Amy. The street she lived on was just a fifteen-minute walk from the campus: a highly desirable area that used to be a hotbed of academia and government intelligentsia, but they’d been done away with and now it was filled with corporate lawyers and speculators and whatever else it was that rich people did. Amy’s husband Pete was an architect who had bought their house cheaply when they were in their early twenties – worst house on the best street – and they’d slowly done it up. It was actually a really cool house. Cunt that he was, I had to admit that Pete was a good designer of space. My favourite parts of it were a cubby hole he’d made for the children to hide and play in, which I would have liked for myself, and a brilliant internal courtyard which was completely sheltered from the wind and filled with ferns, flaxes, exotic flowering plants and an overhead trellis with a kiwifruit vine. We hadn’t done it for ages, but my favourite thing to do was to sit in their courtyard and drink with Amy.

Beyond the front door I could hear cellos and a sound like cats in a face-off. Amy homeschooled her kids, who all learned classical instruments and competed in winter and summer club sports at regional levels.

I let myself in and found her in the kitchen, preparing vegetables, which was what she seemed to spend a lot of time doing these days. Her main activity was fermenting, but she also bottled all manner of vegetables and fruits like a farmer’s wife from the 1950s. The stovetop had two large pots on the boil. The water allowance didn’t apply in their house because Pete had installed gigantic water tanks eight years before. Amy ran the taps like it was the year 2000. There were a gazillion cauliflower florets on the kitchen counter, and on their large dining table alongside children’s books, pens and about twenty glass jars there was a fungal-looking bubbling growth leaking out of a bowl onto an iPad in a slow-mo explosion.

‘That looks nice,’ I said, pointing at the explosion.

‘Oh, fuck!’ she said. ‘That was supposed to be Kate’s responsibility.’

Amy’s children had responsibilities.

‘What is it?’ I said.

Amy immediately started to rescue the bits that were growing on the iPad screen.

‘Can you move the caulis?’ she said, nodding at the kitchen sink.

I picked up three whole cauliflower heads. ‘Triplets,’ I said, rocking them in my arms like they were babies.

She smirked and her face went pink as she moved the exploding growth to the kitchen counter. She’d always been given to blushing when she was amused or embarrassed or drunk or angry. Men liked it.

‘What is that?’ I said, pointing at the brown bubbles.

‘It’s sourdough. It’s vigorous.’

‘It’s definitely in the top percentile. And I guess there was a run on cauliflowers,’ I said, holding them up.

‘Two for ten at the shop yesterday.’

‘Funny what counts for a special these days,’ I said.

Amy’s face was hard. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘we know the solution, right?’

I didn’t say anything. Amy was always getting at me to dig a vegetable garden, which was something I was never going to do. I was happy to fade away to my death when the industrial food chain was gone. But not Amy. Two years earlier she and Pete had built an insulated cool store under their house and put in shelves that were four jars deep in preserved vegetables.

Stella, her middle child, ran in with a cello bow held high in the air, followed by Jimmy, the baby of the family. They still called him the baby, even though he was clearly a small boy now. He was holding an electric drill and pointing it at his sister. The children ran around the table twice.

‘Stop!’ Amy shouted. ‘Don’t run inside! Put that thing down, Jimmy!’

They didn’t stop. That’s one thing I’d learned about kids – they only hear the bits you don’t want them to.

‘He’s trying to drill into my kidneys,’ shouted Stella.

Amy yanked the tool away from Jimmy. She put an apple into his hand and he bit into it like a bad machine.

‘He’s evil,’ said Stella.

She glared at her brother and I glared with her, because she was right. Jimmy was evil.

‘He’s hungry, Stella,’ said Amy, handing her an apple. ‘He gets hungry at this time of night. It affects his blood sugar levels. Now, Stella – you can go back to practice. Jimmy, you stay put.’

I sighed. Jimmy was my least favourite of Amy’s children and Amy’s most favourite. She definitely treated him so, and it was ruining him. Already I could tell that he had the same mercenary traits as his father. He sat at the head of the table, chewing his apple and narrowing his eyes at me.

‘When you leave?’ he said, spitting bits of apple onto the table.

‘Jimmy! That’s not polite. Did you say hi?’ said Amy. ‘We say hello to our guests, you know that.’

‘Hi,’ he said in his cold killer voice.

Stella was standing by the table, hopping from one foot to the other.

‘I don’t want to practise, Mum! It sounds like shit,’ said Stella.

She was right.

‘Don’t say shit,’ said Amy. ‘And you must practise if you’re to improve.’

‘I don’t want to improve,’ said Stella.

The screeching cat sound got louder, and Kate appeared in the kitchen door with a violin under her chin.

‘Mum!’ She shouted even though she was now in the same room. ‘Stella’s not even practising!’