7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

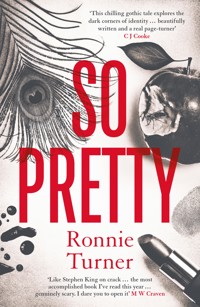

A young man arrives in a small town, hoping to leave his past behind him, but when he takes a job in a peculiar old shop, and meets a lonely single mother, everything changes … with devastating consequences. A chillingly hypnotic gothic thriller and a mesmerising study of identity and obsession. 'This chilling gothic tale explores the dark corners of identity … beautifully written and a real page-turner' C J Cooke 'Dark, lyrical and intriguing' Fiona Cummins 'Like Stephen King on crack … the most accomplished book I've read this year. Dark, gothic as hell, and genuinely scary' M W Craven 'Eerily atmospheric, with brilliant characterisation … really gets under your skin' Culturefly ––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Fear blisters through this town like a fever… When Teddy Colne arrives in the small town of Rye, he believes he will be able to settle down and leave his past behind him. Little does he know that fear blisters through the streets like a fever. The locals tell him to stay away from an establishment known only as Berry & Vincent, that those who rub too closely to its proprietor risk a bad end. Despite their warnings, Teddy is desperate to understand why Rye has come to fear this one man, and to see what really hides behind the doors of his shop. Ada moved to Rye with her young son to escape a damaged childhood and years of never fitting in, but she's lonely, and ostracised by the community. Ada is ripe for affection and friendship, and everyone knows it. As old secrets bleed out into this town, so too will a mystery about a family who vanished fifty years earlier, and a community living on a knife edge. Teddy looks for answers, thinking he is safe, but some truths are better left undisturbed, and his past will find him here, just as it has always found him before. And before long, it will find Ada too. –––––––––––––––––––––– 'An utterly chilling psychological horror of modern-day witchcraft, possession, murder and madness' Essie Fox 'Compelling and dark – draws you in from the very first page' Heather Darwent 'Twisted, toxic and deeply dark, this gives off Needful Things vibes – and that ending is just *perfect*' Lisa Hall 'This book sucks you in from the first spine-tingling chapter and weaves a dark, twisted and compelling sense of foreboding' Claire Allan What readers are saying… ***** 'I'm shook. This book is a force … a masterpiece' 'An ending that left me slightly dumbstruck' 'As delightful as it is dark, with beautiful turns of phrase that can be at once both buttery soft and sharp as a knife' 'Intense, creepy and utterly chilling' 'A story that will creep under your skin and leave you desperately unnerved' 'Startling and incredibly intense' 'Exactly what I look for in a gothic thriller!' 'Deliciously dark' 'It shook me to the core' 'Dark, chilling, with a touch of genius' 'Twisted and unnerving' 'Beautiful and lyrical prose brings the setting to life and creates a pulsing tension' 'This book creeps up on you…' 'Captivating and claustrophobic'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 389

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR SO PRETTY

‘So Pretty is like Stephen King on crack; the most accomplished book I’ve read this year. Dark, gothic as hell, and genuinely scary, Turner has managed to portray loneliness, obsession and monster-worship in one neat little package. I dare you to open it … Oh, and that curiosity shop is the stuff of nightmares’ Michael Craven

‘Dark, lyrical and intriguing’ Fiona Cummins

‘Twisted, toxic and deeply dark, this gives off mega Needless Things vibes – and that ending is just perfect. Brava’ Lisa Hall

‘What an incredible read. This book sucks you in from the first spine-tingling chapter and weaves a dark, twisted and compelling sense of foreboding. It will get under your skin. Brilliant’ Claire Allan

‘An utterly chilling psychological horror of modern-day witchcraft, possession, murder and madness. Who knew such evil could lurk in the heart of Rye?’ Essie Fox

‘Beautifully written and a real page-turner, this chilling gothic tale explores the dark corners of identity’ C J Cooke

‘So chilling, the nature/nurture debate is perfect for a contemporary Gothic thriller – the stuff of nightmares!’ Anne Coates

‘I read this book in almost one sitting. It had me completely rapt. Gothic, dark and fast-paced, it’s a brooding thriller that had me asking new questions with every page-turn. Turner’s prose is as delightful as it is dark, with beautiful turns of phrase that can be at once both buttery soft and sharp as a knife. I had a lot of fun reading this one!’ Rheannah, Bookseller

‘A dark, intense read that’s intricately and beautifully written. This is a story that will creep under your skin and leave you desperately unnerved’ Emma, Bookseller

‘It was unsettling, it was unnerving, it was bloody brilliant’ From Belgium with Booklove

‘Written with a classical nod and containing dark and beautifully observed pen portraits, So Pretty is startling and incredibly intense, and it engenders an atmosphere of fear and dread’ Live & Deadly

‘I’m shook. This book is a force … a masterpiece’ Emerald Reviews

SO PRETTY

Ronnie Turner

Contents

For Maggie

HELP WANTED

Berry & Vincent

Sales, stocktaking, general upkeep. No experience required. Apply within.

Come to Berry & Vincent

TEDDY

Berry & Vincent

The shop stands apart from the rest, bent and misshapen. ‘Keep clear,’ its strange face seems to say. ‘Keep away. We are closed to you.’ Though, obviously, it is open.

A sign hangs above the door, tossed by the rain with a sound like: begone, begone, begone. Even this small thing does not care for my presence here.

Berry & Vincent

Ye Olde Antiques and Curios Shoppe

Purveyors of fine antiques, oddities and collectables.

Est. 1970

There is something malignant about the place. The blinds are up, its eyes are open, and I wonder if I have made a mistake in coming here.

‘Oh,’ I say to nothing. ‘Oh.’ Have I?

The best the shop window can boast are a fine, golden music box and a pair of emerald gloves in rich and buttery suede. A mask hangs there too, black eyes and waxy skin. I imagine it is made of some sort of rubber and I want to press my finger into its cheek and make it smile.

Drawing my woollen coat tighter, my reflection surprises me. The skin on my face seems loose, drooping like wax over the edge of a candle, an old man. A visual contradiction of my thirty-three years. The street is empty. The rain, the rain, I tell myself, it’s because of the rain. It isn’t because of me. I haven’t frightened away everyone on my second day in Rye.

I look back at the mask…

But it’s not a mask, it’s a man.

He blinks, and I wheel back, heart stamping. Courage, courage, Teddy. I straighten my coat, run a hand through my hair.

A bell chimes as I push open the door. Black pillars quiver in front of my eyes, then they still and I realise they are towers of things. I worry I might stumble and break something.

Or something might break me.

The man from the window slithers forward. I wait for the inevitable jolt of recognition, the expression on people’s faces when they look at me. It doesn’t come. Perhaps he does not remember who my father was, perhaps he does not know this face I wear. My leg jigs. I take a breath, stick out my hand.

‘Hello. My … my name is Teddy Colne. You’re Mr Vincent? It’s nice to meet you.’

His hand is slick, and I must keep myself from wiping mine on my trousers. ‘Thank you for accepting my application. I look forward to starting work.’ Again, nothing.

‘You have quite the place here. It must have taken a long time to build such a collection of … things.’

He walks away. I follow, wringing my hands. Should I just slip out? Would it be so bad if I simply left? No. I can’t. This is my fresh start. I sniff. Even if it isn’t all that fresh.

‘I don’t think I’ve ever seen a shop like this before. It’s … impressive.’ Compliments; the crutch of desperate men. ‘This is my second day in Rye. Is it always this quiet? Perhaps it’s the rain. It’s a grim day. Heavy. Sends everyone indoors, doesn’t it?’

How old is he? His hair is the colour of chalk, his body is bent, and sweat, sweet and sickly, wafts from his frayed clothes. I guess he is in his seventies.

‘Gosh, I haven’t seen one of those since I was a boy. Oh look!’ He does not look. ‘Very impressive,’ I mumble. ‘Very impressive.’ But I am thinking, Speak! Speak!

The shop stretches back, a cavernous hallway bloated with broken clocks, buckets, books, dolls with blue eyes, brown eyes, black eyes, no eyes.

But there is more.

Shelves laden with curious curiosities. A tin brimming with bodies, fleas, small as crumbs of bread. A stuffed terrier with two noses. A human foetus lolling in a jar, half-formed eyes like five-pence coins. Rubbery bodies and leathery faces in jars, in buckets, in corners where I am afraid to step.

I see photographs on the wall. From the 1900s perhaps? Faces, faces, so many faces, ivory pale, lips dark as a bruise. They watch me. And I wish they would not. My feet clump to a stop. Their eyes are glass, shiny and strange, almost as if … I realise then. These are photographs of the dead.

And.

‘Are they childr—?’

But I have no words. They have run out of me.

Twice more, I consider fleeing, hoping some creature doesn’t trip me on my way. I wonder if he is a mute, Mr Vincent, some voiceless, wordless little fish of a man. But I hear him mutter to himself as he watches me complete my tasks, hear him curse my clumsy hands, fury in his strange voice.

‘Why will you not speak?’ I ask him eventually, with more courage than I know I have.

He looks at me. I apologise.

He speaks. So why doesn’t he speak to me?

Will I find him tomorrow, tucked inside that shop, all the blood and bone gone from his body? A man with porcelain skin and a horsehair wig, grown into one of his many peculiar items?

Now, at home, shuffling out of my coat, I move with all the speed of a ninety-year-old man. My knees ache, arthritis swells them to melon-shaped bulbs. But it is not only this. I take a shaky breath. I feel thinned, stretched. I was only inside a shop. But the shop feels as if it is still inside me.

ADA

Curio and Curiosity

The first time I saw Berry & Vincent I told myself I wouldn’t go inside. Its shadow spilled into the street, and I stepped back so it could not meet my shoe.

Albie’s eyes were bright-blue saucers as he looked at the trinkets in the window. He dived inside, and I went after him, the single light casting a yellow haze that made the shadows blister, grow sharper. Sharp enough to cut. Albie reached for something and I snatched his hand back.

The shop extended, a black hole full to bursting with things I doubted I could even name. A man appeared, smiled, but it looked painful, as if the muscles had lost their ability to flex.

‘This is Albie. I’m Ada. We’ve just moved into the town.’

He licked his lips. ‘Miss.’

That was all he said. Yet I wanted to push that word back between his lips. A tremble rolled down my body, and I put a hand out to steady myself.

Albie tugged my hand, showed me a toy car. I nodded, aware there was only two pounds twenty in my pocket. The man refused the money. I pulled Albie out, the toy still tucked inside his fist, then we ran like the shop was a live thing and it could crack us between its teeth.

‘Have you met him?’

‘Who?’

‘Teddy. He’s just moved here. Works at Berry & Vincent. He’ll come to regret it soon enough. There hasn’t been an “assistant” in all the time I’ve lived here. Can’t know what he’s got himself in to.’

‘He’s really the first person to work there?’

‘Yes. That place will put a rot in his belly. It will make him sick. You’ll see.’

‘Where’s he from?’

‘How am I supposed to know that?’ She shakes her head. ‘First newcomer since yourself. Two years you’ve been here now, isn’t it?’ A look, swift, scathing. There are two others in the grocer’s; they look up when she mentions the newcomer, hands stilled on cans of soup and bags of apples. Now the women look away again.

‘I wonder why he wants to work there,’ I say, remembering the first time I saw Berry & Vincent.

‘Where’s that boy of yours?’

‘He’s home asleep. He’s poorly. He could wake up any moment. I should go.’

Albie is just as I left him, curled up tight as a fist. I ease myself into bed. His eyes ping open.

‘Hello, sweetheart. How do you feel? Any better?’

‘My head hurts.’

‘It’s no better?’

‘No.’

‘Oh dear. It will be soon, I promise. I’ve got beans and toast for supper if you can manage it later?

‘Mrs James was worried about you.’ A lie; she couldn’t care less. ‘She hopes you feel better soon. She told me that someone new has moved into the town. He’s working at Berry & Vincent.’

He frowns, creases settling between his eyes. ‘Who?’

‘I think she said his name is Teddy. Like a bear.’

He smiles. ‘Why does he work at Berry & Vincent?’

‘He’s the new assistant. He’s going to help out in the shop. Come on.’ I give him his glass of water. ‘Have a little drink.’

After he’s finished, he curls round me, sleeps. I keep as still as I can, but the silence is sharp, and I berate myself for wishing I had stayed longer in the grocer’s because now I am back and I’m feeling the absence of a voice, anyone’s voice, like a fist turning in my gut.

TEDDY

Riddles and Rye

There is more to the shop than I first thought. Before, it seemed to say, ‘Keep clear. Keep away. We are closed to you.’ Now it says, ‘Come. Come now. Come inside.’ And I do not think it will ever open its door for me to leave.

Strange shoals of things are spread throughout. A bowl of bezoars, casual as hard-boiled sweets: a skeleton of a two-headed baby; conjoined pups, pickled in a jar; leathery bodies of creatures I do not know the names of. Faces, faces, faces, all over the godforsaken shop.

I close my eyes to it all, turn to the master of it all, this strange civilisation. Close them again.

‘How … how did you come to have all this?’ I ask, taking up a jar and polishing it. There is something inside, lumpen and small as a golf ball.

He turns and looks at me, but no answer comes. I try again.

‘I’ve never heard of some of these things. Where did you find them?’

My voice is shaky. I swallow, tell myself to speak up. Speak up! Stop being such a fool.

‘What was the last thing you sold?’

He turns, walks away. I stare at his back. It is moving, quivering. Is he laughing? I look down. The lump in the jar is a head. A baby’s head, shrunken and brown as rock, three ivory thorns driven through its lips.

The café is full today, fit to bursting with townspeople. How long in Rye until they recognise me as my father’s son?

I sit in the corner by the window, see the shop, see Mr Vincent moving around in there, this man who watches but never speaks.

I rub my hands together. Look away. Look back.

He’s there.

In the window this time. Looking at me. I jump in my seat, knocking my coffee over. Across the street, a smile turns the corners of his lips.

The first smile of his I’ve seen.

Molly, the elderly proprietress places a hand on my shoulder. ‘Can I get you anything else?’

‘No thanks.’

Molly follows my gaze. ‘It’s bothering you, isn’t it, Berry & Vincent?’

I push out a chair and gesture for her to sit down. She does so hesitantly. ‘It’s … it’s … different.’

‘We don’t talk about the place. It keeps to itself. And we keep to ours.’

‘I only arrived in Rye three days ago, but when I saw it … I was drawn to it. It just, well, it looked unusual. I saw the poster in the window, put my CV through the door and I got the job. No interview. Nothing. I’ve still not quite adjusted to it though. It’s not what I thought it was.’

‘You shouldn’t be working there.’ She bites her lip, draws a single bead of blood before swiftly wiping it away.

This morning, countless townspeople threaded the street but not once did the door open nor its bell ring. And I realise now that they were all avoiding the shop.

But it wasn’t because of me.

‘What’s … what’s the story behind the place?’ I shuffle my seat closer, vaguely aware that four other people have done the same.

‘We don’t talk about the place, Mol. We don’t.’ One of the men shakes his head, fast, until I think it will come off his neck.

I look round, I see only aged faces turned to mine. Only aged faces all around this town. Everywhere I look.

‘He should know what he’s taken on, Phil.’ Molly sighs, fiddling with salt on the table. ‘It was a butcher’s before it was Berry & Vincent. We’d all go there for our cuts of meat every Saturday, have a natter about the week. It was busier than the café some days. Old Bill Norton was a chatterbox, could talk your ear off in five minutes, but he was a sweet man. About fifty years ago, Old Bill had to sell. He moved from the village with his family, who were hankering for the big city.’

‘London?’

‘No, Hastings.’

‘Anyway, one day, they turned up. Mr Berry and Mr Vincent.’ She gestures to the shop. ‘Opened the place two weeks later. Antiques and curios. The town was interested, naturally. It seemed like a good sort of place for the tourists, you know. The kids took a shine to it. All those toys tucked away in there.’

I think, And now he has photographs of dead children on the wall.

‘What about Mr Berry? I haven’t met him yet.’

‘And you won’t,’ she says. ‘He’s long gone. He was here about a year, Berry, before he left.’

‘He wasn’t like the other one. Good man, Berry, good man.’ We turn to see an elderly man shuffling his chair closer. ‘He cared about us lot, he did. Every Saturday, he’d organise a treasure hunt for the kiddies. Hide toys round that shop and get them all involved.’

‘Why did he leave?’

‘No one knows. Not really.’ Molly now. ‘But we suspected that he was bought out—’

‘Pushed out, more like.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Vincent. He did it. Been infecting this place ever since. It was better before.’ The elderly man’s voice needles in my ears.

‘Now, we’ve talked enough about that place. You’re scaring the poor boy.’ Molly, silencing the others with a look. ‘Stop.’

I sit back, realising that the café is oddly still, the hum of voices has fallen away. Eyes watch me with sadness, fear … pity. I shrink back from it, stumbling as I rise from the chair. ‘I should probably go and explore the village. I’ve only seen a bit of it. It was nice to meet you all.’ I laugh. Why am I laughing?

‘If you need anything, anything at all, even if you just need someone to talk to, come to me. I’ll help you.’ Molly reaches for my hand, the salt on her fingers pressing deep into my skin.

With what?

‘With him.’

I had not realised I’d spoken.

‘Thanks.’ I close the door behind me, but I feel these people looking at me as if there is a sickness already inside me.

ADA

Rotten and Pretty Things

‘How long, do you think?’

‘How long until what?’

‘Until he runs.’ The men walk by my living-room window, greasy chins thrust out. Their feet, thump, thump across the ground, as if they have heartbeats in their saggy boots. I watch them, Albie sleeping in my arms.

‘A month, I’d say.’

‘Won’t be long. Poor lad. He’ll turn. Like milk gone sour, stinking up the kitchen. It’ll get him. That shop will get him.’ There is sadness in his voice, and his words droop his shoulders a little further down his body.

‘The wife’s going to take him one of her lasagnes this evening.’

‘Hmm.’

They are quiet then, pausing by my window, trying to look at each other without moving their heads. Eventually, the smaller one speaks, and it is a boy’s voice from a man’s mouth. I think how fear makes people small precisely when they need to be tall.

‘I saw him standing outside Berry & Vincent the other day, you know. Just standing there, watching it. Like a lost thing.’

‘He didn’t go in?’

‘No. When I asked, he told me it was his day off. But he went there anyway…’

‘Why?’

‘He said, the place was inside his head. And he couldn’t find a way to get it out.’

I think of the shop then. Buttons, black, silken rolls of red ribbon. Hearts of hummingbirds in beaded purses; music boxes lined with whales’ lung tissue; black and blue feathers from birds shivering above. The shop is asunder, a tangle of things, and you must watch your step, keep your breath in your body so you don’t break anything and nothing breaks you.

When we arrived in Rye, the townspeople would not speak of the place.

‘It’s a curious box and a box of curiosities. We don’t go inside Berry & Vincent,’ they said.

‘Why?’

‘Don’t go inside Berry & Vincent,’ they said. ‘There’s a devil inside that place.’

Their lips pinched and they shook their heads. My questions about this strange shop, the strange shadow it poured across the street, went unanswered.

‘It’s an unkind place. Leave it be. And it will leave you be,’ they said.

‘But—’

‘Leave Berry & Vincent be.’

TEDDY

Superstition and Suspicion

I can’t remember what first drew me to Rye. Perhaps it was the Tudor cottages leaning like drunks down the slope of cobbled street, or a sense that here things could be hidden, forgotten.

The Mermaid Inn sits to my right, half-timbered with a sloping slate roof and mullioned windows. The place smells of chips and ale, a heady combination that makes my stomach roar. I find the bar and order lunch. ‘This place is impressive.’

The elderly landlady grins. ‘Thanks. We like it. We don’t get many tourists in February so I’m going to take a punt and say you’re that newcomer?’

‘I am. I’m Teddy.’

‘Charlotte. Heard there was fresh meat in town. How are you settling in?’

‘It’s … a challenge. I’ve just started work at the antiques shop. Molly doesn’t seem too keen on the place.’

‘You won’t find many who are.’ She takes up a tea towel and picks at the thread. ‘That place casts its own sort of shadow.’

‘What do you mean?’

She shakes her head. ‘Nothing. Ignore me, son.’

‘Please.’

She studies my eyes, my lips, my nose. Panic threads itself though my chest, but finally she speaks and I breathe. ‘It looks different now, feels different now. Parents warn their kiddies off going in there. We steer clear of it.’ She pauses, eyes as wide as plates. ‘No one knows much about Mr Vincent. He and Berry just arrived one day. Arrived with the rain. I remember because it was one of the driest summers on record. But that day it was like God was trying to drown the town.’

‘Were they friends or just business partners?’

‘Vincent used Berry, tricked him. He needed his money to get the shop. It was all calculated. They weren’t friends. Barely business partners. Vincent hated him and Berry left a year later. Just disappeared. Haven’t heard from him since. Came and went with the rain.’

‘You have an idea why?’

‘No. No one knows really. Vincent changed this place. We don’t usually talk about him. Or Berry. It’s best to leave it be, son.’

I detect a warning there, a glint of steel in her old eyes that bothers me. A pile of loose thread sits on the counter, a hole in the tea towel.

‘I don’t know why you want to work there. I don’t know why he wanted you, he hasn’t had an “assistant” the whole time he’s been here. But can you do me a favour?’

I nod.

‘Don’t stir this up. There is a reason we keep from talking ’bout this.’

‘What reason?’

She shrugs. ‘Like I said, there’s a rot in that man, like an infection that spreads from his body. But this is still our town and we choose to ignore it. It’s the best way. Look, there are things you don’t know. Don’t stir it up. Please.’

Berry left only a year after the shop opened. But why? Why so suddenly abandon his business, all that he had built? And how has an entire village come to avoid one shop? One man?

But then must I really ask that? Don’t I already know?

Charlotte keeps her eyes down. ‘You’re working there so you’ll notice this soon enough. Don’t think it’s about you.’

‘What?’

‘Kids hold their breath when they pass the shop. As if they might catch something or as if it might take something from them.’

‘Why though?’

‘Watch, you’ll see the children hold their breath when they pass by Berry & Vincent.’

ADA

Day and Night

I was in Sainsbury’s toilets when I discovered I was pregnant. The lights were flickering over my head, and the smell of perfume and urine put a sickness in my throat. I remember hearing the woman in the next cubicle cursing as she tried to pull up her trousers.

I was twenty years old. The father, my first and last one-night stand, I have no name for. He was a quick distraction, one my three closest friends encouraged me to enjoy at a party. The next morning I left, thinking it wasn’t worth the eleven pounds fifty I had to pay for a taxi to his place.

‘Boy or girl?’ A librarian asked once when I was in my first trimester, seeing the books I carried. ‘I’ve always wanted a boy but I got four girls.’ Like it was some snub from fate, dealing her duds.

‘I – I – I don’t know.’

‘Have you thought of any names?’

I hadn’t. ‘No yet,’ I said. In all honesty, I had forgotten about that part.

My body stretched, reaching new contours as I sprayed bottle after bottle of cheap perfume in the bathroom every morning to mask the smell of sickness. The skin on my stomach grew thin, scarred, I could follow the veins with my little finger, like some strange game of snakes and ladders.

I told everyone eventually, when my blister of a bump became too difficult to disguise. My mother’s reaction was as I expected it to be. Her fury lasted a whole week – the air in the house was bursting with it and I took small breaths so I didn’t choke.

‘Get rid of it. You disgust me. Get rid of it!’

‘No.’

‘I shan’t have it in my house. Your mistake, your problem. You’re a fool, Ada Belling.’

‘I’m not getting rid of it.’

‘Disgusting!’

The word flew like spittle, smacked my cheek. I lifted my finger, pressed it to my face, but, of course, there was nothing there.

She packed my things, throwing the bags outside, the value of my life less than the empty bottles and balled-up wrappers she took such care to recycle.

Father was no help. I went to my aunt’s after that, waited out my final trimester in the company of my three boisterous young cousins, who poked my bump until my aunt threatened them.

‘I mean it, Andrew, stop poking her. Jesus. She’s not your hamster.’

‘God. Look. Her stomach just moved!’

‘That’s the baby kicking.’

‘Sick!’ said Andrew.

‘That’s just nasty,’ said Patrick.

I did not see my mother again after that. She is cutting, nails always risen to harm. Even her bones have sharp edges. I recall standing at the bus stop, six years old. A boy my age was clinging to his mother like a monkey, soft young paws. But when I did the same, mother pinched my fingers. ‘Don’t do that.’

I sucked the redness, looked at the boy looking at me. I realised then I could not take love from a body.

TEDDY

Boy and Man

I see them. The children who hold their breath when they pass. Cheeks tomato bright. Feet quickening. I hold my own sometimes. Or have I just stopped breathing?

I have few responsibilities within the shop; these include cleaning and wiping down, pricing, occasionally helping Mr Vincent adjust some of the larger articles on display. I must not change the order of things, I must not rearrange or tamper without permission. If I should move a pen but an inch, he will move it back. I am not allowed to open the till although I am allowed to stand behind the counter.

I keep to these duties, I do not overstep.

‘It’s quiet. Almost wish it would rain. Something to listen to.’ I am talking to myself because silence is a strange thing, it turns the mind in on itself. And he will not allow me to switch on the radio. ‘Grim today. Always loved the sound of rain. My mum used to say God was in the rain. Never did understand that. Don’t think she did either, really.’

I do not know where he is, where this peculiar person ends and the shop begins. They are bound together, as if with a crude row of stitches. Perhaps they really are one thing.

A book slips from my hand, and the binding cracks. Suddenly there is wool in my throat because I cannot breathe or speak. The shop has quietened, as if even it is alarmed by what I have done.

I bend, take it up, rise and, he is here.

A gasp slips from my lips. He snatches the book, his arm swinging back, and I think he is going to beat me with it. As my hands come up to my head, he turns, blends into the chaos. But the chaos in my chest will not calm.

It is quiet at home. Quiet there, quiet here. I like to press my fingers to my ears sometimes, until they throb, then I speak and I do not sound like myself. I sound like someone else. I unplug my ears, I plug them, and I am two people.

I have done this since I was a boy. It is a comfort to me. Because the radio and television do not listen, they do not respond. I close my eyes and I am back in my old flat, the first place I had of my own.

The carpet has a constellation of holes – moths, mice, I still do not know from which. There is a black fur on the wall, with each breath of mine it grows. And there is the quiet. I thrust a ready meal into the microwave. I own only one fork, one knife, one spoon. I do not need more. But tomorrow I might buy a new set. I might set the table, cook for two. The food will go cold, but I can tell myself it goes cold because someone is running late and not because there is no one coming at all.

I plug my ears:

‘How was your day?’

‘Rubbish. Yours?’

Yours?

I like how it sounds, someone asking after me.

Tomorrow I will pour wine, rub some red over the rim. There look! A woman has been here. Her lipstick, see … see?

‘I see,’ I say. ‘I really do.’

I am not a boy anymore. My skin is baggy, my hair thin, arthritis swells my knees, makes me walk with a tilt, as if I am always about to fall over. But now I am adept at becoming unknowable. I can pack up my homes in twenty minutes, I can fill my car, begin the run, to the next place, the next, leave those blinking faces in my rear-view.

They looked for it inside me – that rot. Sometimes it can take months, sometimes only a day, but in the end, I am recognised as his son. ‘Don’t watch his lips,’ folk said of him. ‘Watch his eyes. His eyes can’t tell a lie.’ And now they say it about me.

‘There’s a rust on you, boy. Red as the Devil’s skin. I’m not letting any of that rust get on me. I might not get it off.’

He liked children. Little girls. Their innocence, their purity. He took them between the ages of six and twelve. Only they would do. My young foster ‘brothers’ used to call me Killer’s Boy. They’d take their fork, stab it into my hand and the ‘parents’ would bluster at the blood on the tablecloth. I have no memories of my father, I did not know him, yet I am condemned for all he has done. Because, somehow, it is all that I have done too.

TEDDY

Birds and Bottles

My mother’s mind wandered and it did not come back. When I was a child, her voice was always so clear and loud.

‘Loud as a bell, Mum.’

‘If you shake me, I’ll ring,’ she joked.

‘I’m shaking you, Mum. I’m shaking.’ My arms round her middle, moving us back and forth.

‘Ring, ring.’

We laughed because it was funny. We could not imagine a time when it would not be.

But the years passed, folded in on us. Shame and guilt for my father’s crimes quietened that bell. As a boy I did not know what tormented her, why she would go still during the day, like a wind-up toy stuttering to a stop. Or why she would run to me suddenly, faster than I had ever seen her run, gather me in her arms. So I kept still, breathing hard against the itchy wool of her jumper, tighter, tighter, but not wanting to ask her to stop.

There is a bird in a bell jar. With needle-thin feathers and a beak just a grain of rice. It’s a blue tit; I know because my mother used to love watching the birds outside our home. As a boy I’d pad downstairs, find her hovering in the doorway, and she’d let me sip from her mug.

I run my finger over the domed glass. Let him out, Teddy. He can’t even stretch his wings. How would you feel? You’d feel trapped. Let the bird go.

I can’t, Mum. The bird doesn’t belong to me.

The bird belongs to no one. Birds are free.

I do not know how long I have worked here. Days are months in Berry & Vincent. Time is an unfamiliar thing, it does not behave as it should. Mr Vincent. He is there when a moment ago he was not. I feel as if he’d like to take me apart, put my bones in neat piles, polish my skin, see my thoughts, like a cloth to a gritted window.

Who is he? And who am I to him?

I recall a conversation this morning with my neighbour:

‘How are you settling in?’

‘Very well, thanks.’

‘Where are you from? I don’t recognise your accent.’

‘Reading.’ A lie. I never tell anyone where I’m really from.

‘I have a grandson who lives there. And how are you settling in Rye? How are you finding Berry & Vincent?’ She spat its name.

I wiped my chin. ‘It’s … it’s taking some getting used to.’ What else could I say?

‘I remember when he came to this town. I saw him once, you know, it must have been about five years ago now, through the shop window. He was talking. But he never talks, I said to myself. So I went for a close look. You know what I saw?’

I forced myself to smile.

‘No one. Not a soul. The shop was empty. He was talking to his things. All those strange things tucked up inside there. Just talking.’

Brown bottles, copper pans, pocket watches on a bed of green velvet. Wax dolls, porcelain dolls with full pink lips, pursed to kiss. Or bite. Voodoo dolls stuffed with straw; a hand in a preserving jar, a lump of cancer across the thumb joint; shrunken tsantsas heads hanging together like strange baubles.

Why does he have all this? Why did he advertise for an assistant? And why hire me?

I move behind the counter, a barrier between myself and these questions, these strange faces inside the shop. There is a drawer open, cutting into my leg. Usually it is locked, the key kept somewhere on Mr Vincent’s body. I wonder if he left it open for me. Or did he simply forget? Inside is a leather-bound book, heavy as a brick, curling at the edges. I open it and see hundreds of photographs, Mr Vincent’s scrawl fanning around them. Everything in this place has been catalogued, studied. Revered.. This is not just a shop, this is a collection. His personal collection. I back away, my breath caught like a rock in my throat.

‘Jesus!’

I’m slouched over a plate of fish and chips in The Mermaid, the salt and vinegar pricking my nostrils, but I can’t stomach it. Sweat has dried on my skin, a covering of it that makes me itch. How does he afford his collection? How does he pay for the shop? Is he funding it with his own money? There are no customers.

Charlotte smiles at me from across the room. I wave and she reluctantly comes over, grey curls bouncing on her neck. I offer her a seat. ‘Something the matter with your meal, son?’

‘It’s fine. Can I ask you about the shop?

‘No. Not about the shop. I’ve told you that already, son.’

I touch her hand, then snatch it back. I’m overstepping the mark but I am desperate. ‘Please.’

She glares at me, folding her arms. ‘Fine. Because I don’t think you’re fully aware of the job you’ve taken on.’

‘I don’t think I am either.’

‘What do you want to know?’

‘When was the last time you went in the shop?’

Her mouth pops open. ‘It … well, it was years ago.’

I lean closer to her. ‘How many years ago?’

‘Around the time Berry left. Why?’

‘What was the shop like when Berry lived here? What was it like inside?’

‘Well, it was just a shop. Lots of tat. It was a bit cramped. Stuff everywhere. Toys and old clothes. Jewellery, clocks, even had a unicycle. The kids used to go in there and mess with it, spin the wheel round and round. Berry thought it was hilarious. He’d let them do whatever they wanted, as long as they were careful.’

‘Where was Mr Vincent?’

‘He used to just stand behind the counter or disappear into the back room. He never spoke to us.’

‘Do you remember anything odd inside? Anything that seemed like it didn’t belong in a little junk shop in Rye?’

‘What are you talking about? It was just full of crap. Stuff the kids liked and the tourists bought cheap.’

I nod. It changed after Berry left. That was when he must have started his collection. When the shop became his.

‘You look very pale. Just a minute.’ She goes to the bar. ‘Here.’ She passes me a glass of water, three fingers I wish were vodka. I gulp it down nevertheless, and suddenly there is an ocean inside of my stomach, waves roiling, curling, restless. It makes me sick.

‘Thanks.’

‘My old friend came to the town a few years back. To stay with me and my husband for the week. She wanted a break from the city.’

‘London?’

‘Hastings. Why do you keep asking that?’

‘Sorry.’

‘Anyway. She told me she went in the shop, but the whole time she just wanted to bolt. Said it creeped her out. When she went to pay, she said the man, the proprietor, was behaving weird. Kept fidgeting, twitching, sort of. She told me it was like he didn’t want her to have the books. Like none of the stuff in there was for sale.’

It’s not.

I suck in a breath, the tension built up over the morning making me feel lightheaded, winded. All my suspicions have been confirmed. ‘Did your friend say anything else?’

‘No. But I could tell it bothered her.’ She pauses. ‘Has … has he ever behaved like that in front of you?’

‘There have been no customers. How does he even keep the place open? He never sells anything.’

‘Tourists. The summer season is always profitable for him. Apparently. He hasn’t gone out of business, after all. Does it bother you? Working there?’

‘I…’

‘It’s OK. You don’t have to tell me. I was just wondering.’

I want to tell her everything – he watches me but never speaks – I don’t, though because I don’t know how to frame the words.

‘I … Well, I suppose I was taught to keep going, not to give up.’ It’s a weak answer and she knows it.

‘Right, well, that’s very noble of you, son.’ She shakes her head, and I can’t tell if she pities me or thinks I’m a fool. Both. She stands, glances at my untouched meal. ‘I’ll let you eat. Have a good day, Teddy.’

She heads to the bar. I want to call her back. I don’t because then I would have to give her the truth: Berry & Vincent is a distraction. Beside the shop, I am a nonentity. No one spots the tell-tale clues in every line of my face, my father’s face. How can I leave that? When I have been looking for anonymity for so long?

ADA

Everything and Nothing

I stand by the window and listen to the voices in the street:

‘He shouldn’t be here. Why has he come? Why work there? Of all the places.’

I know who they are speaking about. Come, come to the window, I think, I want to know more. But they do not.

‘He’s stirring things up. He’s waking up a lot of ghosts.’

‘And more besides.’

Berry & Vincent, of course. And the strange man arrived in Rye to work there. ‘He must be strange,’ one says. ‘How can he not be, working there?’

‘Oh but he’s not strange. Not like that. He just doesn’t know what he’s got himself into. That’s what Molly says. He will do soon enough.’

‘What can he do all day in there? Has he said anything about him? Mr Vincent?’

‘No.’

‘I saw him the other day through the window. He was stood behind the counter. He looked frightened out of his wits. He was polishing a … a—’

‘What?’

Her face empties of expression. ‘I don’t know. I don’t know what it was.’

‘He should leave.’

‘He should leave.’

TEDDY

Needle and Thread

She laughs when she squats and pisses against the wall. And when she holds a spoon to her eye, says, ‘Look at this little fork.’ Fat tears slosh onto her cheeks. There is much in her face, I do not recognise now.

Every morning, I bring her a cup of tea because I don’t want her to feel glum when she wakes. ‘Tea makes everything better, Teddy,’ she used to say. She doesn’t say it anymore.

‘Morning, Mum. Good sleep?’

‘Johnny, your bathwater was filthy last night. What were you doing while you were away?’

‘Mum?’

‘Soil. So much soil. I had to scrub that tub clean. Took ever so long. You been rolling round in flower beds?’

‘No.’

She means the girls. Where he took the girls.

‘I’ve made you tea: milk, three sugars. How you like it.’

‘I have my tea black.’

‘No you don’t, Mum. You can’t stand anything bitter. You’ve always taken it like this.’

She harrumphs. ‘You’ve not answered my question. Where were you?’

‘I was nowhere.’

‘Well you must have been somewhere. They run you ragged with that job. All that driving. You hardly spend any time with your son. You’re going to miss him growing up. I keep telling you this.’

‘He wasn’t delivering packages though, was he, Mum? Don’t you remember? Why don’t you have some tea and relax?’

‘It’s got to be black, Johnny. Never mind about the coffee now. Were you listenin—’

‘Tea, Mum.’

‘Do you want to miss your little boy’s childhood delivering all these packages to God knows where? Hmm? Take some time off.’

‘It’s not coffee.’ There is a lump in my throat, a lot like a coffee bean.

‘You’re going to miss it. You love Teddy. Be there for him.’

‘Yes, Mum.’

‘You love Teddy, don’t you?’

I swallow the coffee bean, scratch at the tear on my cheek. ‘Yes. I love Teddy very much.’

Lines appeared in my mother’s skin, a restlessness sat deep inside her bones so she couldn’t remain still. She’d walk back and forth – you could tell where she’d been by the worn tread in the carpet, then she’d hug me, drum her fingers against my spine.

‘Teddy. Teddy. Teddy. Teddy.’

‘I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.’

But those days didn’t worry me. What did worry me were the quiet days, she could barely move, barely walk, and when she did, she would often come to a halt, I thought I could hear the grinding, like her bones were old machinery.