8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

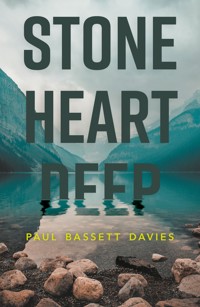

A COMPELLING AND CLAUSTROPHOBIC THRILLER 'Once I'd started reading I could not put it down' IAIN MAITLAND When burned-out investigative journalist Adam Budd's estranged mother dies, he inherits her estate. This includes Stone Heart House, a huge, ramshackle mansion on a remote Scottish island. He visits the island to sort out her tangled affairs, and at first it seems like a charming haven of tranquillity. But after he witnesses a strange accident, he begins to develop suspicions about the inhabitants. Why does everyone seem so eerily calm, even under stress? What is stopping Harriet, the lawyer helping him with his affairs, from leaving the island when she so clearly wants to? Is he making a big mistake by falling for her? And why have so many children gone missing? Stone Heart Deep is a compelling and claustrophobic thriller with a remarkable twist, as if Iain Banks had rewritten The Wicker Man.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Paul Bassett Davies worked in experimental theatre before moving to television and radio, where he wrote for some of the biggest names in British comedy. He also wrote his own radio sitcom, and scripted several radio plays.

He wrote the screenplay for the 2005 feature animation, The Magic Roundabout, and has written and produced music videos with Kate Bush and Ken Russell. He was the vocalist and lyricist for the punk band, Shoes for Industry.

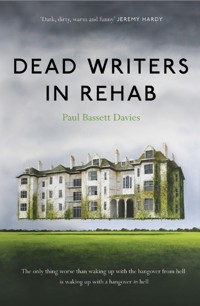

He is the author of three previous novels – Utter Folly, Dead Writers in Rehab and Please Do Not Ask for Mercy as a Refusal Often Offends – as well as a collection of short stories, The Glade and Other Stories.

Other books by Paul Bassett Davies

Utter Folly

Dead Writers in Rehab

Please Do Not Ask for Mercy as a Refusal Often Offends

The Glade and Other Stories

Published in 2021

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Paul Bassett Davies 2021

Cover by Nell Wood

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785632655

Violence is not completely fataluntil it ceases to disturb us

Thomas Merton

Contents

PROLOGUE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

THANKS

PREVIOUS NOVEL

PROLOGUE

The image is blurred.

Adam crouches down a little more, and brings his face closer to the camera. His features spring into focus as he speaks: ‘Is this good, Chris?’

A woman’s voice: ‘Just a moment.’ The image sharpens. ‘OK, all good.’

‘Great. We only get one take for this gig.’

‘Don’t fuck up, then.’

Adam smiles. ‘I won’t, if you won’t.’

‘Deal. Are you ready to go?’

Adam checks his watch and turns to his right. ‘OK for you, Alex?’

‘I’m good,’ says an unseen voice.

‘Let’s do it.’

‘We’re rolling,’ Chris says.

‘Sound?’

‘Sound. And…action.’

Adam speaks directly into the camera. His voice is low and urgent, but steady: ‘In a few minutes I’ll be meeting Enver again. Having come to trust me over the last three weeks, he now believes I’m going to introduce him to Mr Jones, the man who wants to buy the fifteen-year-old Slovakian girl called Nadia. Enver thinks his new customer runs a chain of brothels, where Nadia will be pimped out to men, perhaps as many as twenty a day. In reality, “Mr Jones” is this man beside me, Alex Burnside…’

The camera pans left to take in a burly man hunched down beside Adam, squashed up against him uncomfortably in the cramped surveillance van. Alex nods curtly, and the camera pans back to Adam, who continues: ‘…who served with a British special forces unit before becoming a private security consultant. The men we’re dealing with can be very violent. We’ve already seen how they treat the women and girls they smuggle into the country, including Nadia, who has been helping us with such incredible bravery. We now intend to free her, and expose Enver’s operation. Let’s hope everything goes to plan.’

Adam stops speaking and continues looking into camera.

‘It’s good for me,’ Chris says, ‘and…we’re still rolling.’

‘Let’s go,’ Adam says.

‘Wait, let me switch audio source. OK; test it.’

Adam pats his chest, producing a loud THUD from the microphone concealed under his shirt.

‘Say something,’ Chris says.

‘See you on the other side.’

‘Good for sound. Break a leg.’

Adam and Alex turn around awkwardly, unable to stand upright. Adam opens the back doors of the van and daylight floods in.

The shot swings around. There’s a glimpse of Chris’s hand as she flips open a spyhole in the van’s side panel and places the camera up against it. The focus and exposure are adjusted, and now Adam and Alex are walking away from the van, between two rows of big trucks. The sound is picked up by Adam’s concealed microphone as the two men walk almost to the end of the canyon formed by the parked vehicles. They wait.

‘Here they come,’ Adam whispers. His amplified voice sounds weirdly close, given that he and Alex are a hundred yards away now, at the far end of the commercial vehicle parking lot. The ceaseless flow of traffic on an unseen motorway, somewhere nearby, sounds like the sea.

A large black BMW glides into view, swings slowly into the canyon between the trucks and stops a few yards from Adam and Alex. The front door on the passenger side opens and a man with a thin face gets out. He strides around the back of the car and opens the rear passenger door on the driver’s side. A squat, shaven-headed man emerges, and raises a hand to Adam with a smile. Meanwhile the driver steps out of the car and stands motionless beside it, his hands clasped in front of him. He’s big.

The squat man reaches back into the car, making a beckoning gesture with his hand, palm downwards in the European way. After a moment a girl emerges. Hair in pigtails, short skirt. She looks pale, but she seems steady enough as she stands beside the squat man. Even though she’s clearly very young she’s nearly as tall as him. He puts an arm around her waist and walks her to Adam. He extends his free hand.

‘Adam, my friend. Good to see you again. All OK with you?’

‘All good, Enver. This is my friend Mr Jones.’

Enver turns to study Alex. He nods slowly. ‘Mr Jones. Shall we be on first-name terms, now we finally meet and do business?’

Alex steps forward and offers his hand. ‘Charlie. Charlie Jones.’

They shake hands.

‘OK, Charlie,’ Enver says, ‘now you meet Nadia.’

He draws the girl close, cuddling her as he speaks to her in a coaxing, avuncular tone, his lips brushing against her hair.

‘Mr Charlie Jones is a fine English gentleman,’ he says, ‘and he will be very good to you if you are nice to him. He will buy you gifts, you know?’

Enver winks at Alex, who reaches out to take Nadia by the hand. Enver gazes at him for a long moment before he removes his arm from around Nadia’s waist.

Alex gently pulls her towards him, pivoting slightly as he does so, to place himself between her and the others. The move is casual but deliberate.

‘She is a good girl,’ Enver says to him. ‘Very clean. Fresh. No men yet.’

Alex nods, and smiles blandly. His grip on Nadia’s hand is tight.

Enver turns to Adam. ‘So, it’s good. You have the money, my friend?’

‘No.’

Enver glances around. ‘Who has the money?’

‘There’s no money, Enver. I’m a journalist. You’re being filmed.’

Enver moves closer to Adam. He speaks softly. ‘What are you saying, Adam?’

‘We’ve been filming you secretly since–’

Enver cuts him off: ‘Give me the girl.’

At the sound of Enver’s raised voice, his driver and the other man move forward swiftly. Adam shifts his balance and loosens his arms, ready to fight. Beside him, Alex plants himself squarely in front of Nadia, still holding her with one hand while with the other he whips a thin police-style baton from inside his coat and with a flick of his wrist extends it to its full length.

‘No,’ Adam says, ‘Nadia stays with us.’

In a single fluid movement Enver produces a gun and raises it to point at Adam’s face, very close. Adam doesn’t flinch: ‘This is being filmed, Enver. You’ll get eight years or so, serve four, maybe get deported. Murder will get you life. Twenty years minimum.’

Enver’s hand remains steady.

Adam says, ‘That white van behind me? That’s where the team is. They’re calling the cops right now.’

Enver’s eyes flick away from Adam’s face and, unnervingly, he looks directly into the camera for an instant without knowing it. He returns his gaze to Adam’s. He lowers the gun, takes a swift step back and shouts to his men: ‘We go!’

Adam glances at the driver and the other man as they run back to the car. While he’s distracted, Enver raises the gun again and whips the barrel across Adam’s face.

Adam staggers but doesn’t fall. Enver and his men jump back into the car, which reverses at high speed and clips the back edge of the last truck in the row as it swings around with a squeal of tyres and roars away.

Adam turns to the camera, his hand clamped over his bleeding cheek. He grins and winces at the same time. ‘Tell me you got all that!’

The image freezes.

***

A thunder of applause.

I glanced back up at my own image, huge on the screen behind me. Insufferable prick. That was what part of me thought, anyway. I looked out at the audience. The ballroom was filled with fifty round tables, each seating a dozen people, some of whom were now rising to their feet, presenting the others with the choice of joining the standing ovation or seeming ungenerous. To me. The person they were all there to honour and validate. And part of me loved it.

I was aware that I cut a dashing figure, both up on the screen, where I looked tough and dishevelled – the wounded hero – and onstage, in a tuxedo that still fitted me as well as it did when I bought it, at the age of nineteen. That was two decades ago, and there was still no grey in my hair. Good posture, nice smile. I scrubbed up well, and I knew it. And part of me hated it. This isn’t meant to be about me, I thought, and immediately realised how stupid that thought was. Of course it was about me. I was the one receiving the bloody award, which was currently in the hands of a tall, elegant woman of sixty standing beside me in front of a microphone.

‘The footage we’ve just seen,’ she said, ‘like the rest of Adam’s remarkable work, speaks far more eloquently than anything more I could hope to say. I will simply end by telling you I’m certain that my late husband would have been the first to applaud this choice. And so it is with great pleasure that I present the Simon Draper Investigative Memorial Prize to Adam Budd.’

Another explosion of applause. Those in the audience who were old hands at this game had wisely remained on their feet, to avoid repeating the awkwardness of deciding whether or not to offer another standing ovation.

The woman – Lynn Draper – handed the award to me. It was an ugly, abstract collision of metal and glass, which might charitably be interpreted as symbolising a probing, penetrative spirit, expressed as a collection of spiky protrusions. I grasped the angular lump of kitsch in my hands, and Lynn leaned in to kiss me on the cheek. She whispered, ‘Simon would be proud.’

I ducked in acknowledgement, very nearly head-butting Lynn as she moved in for a kiss on my other cheek, which I wasn’t expecting. We manoeuvred through the moment gracefully, and as Lynn hugged me I tried to prevent the award, which I was holding in front of me, from stabbing either of us in the belly.

Lynn stepped away, and I placed the award on the lectern in front of me. I kept one hand curled around its narrow stem, mistrusting its stability.

I leaned into the microphone and did my thing. I thanked each member of my team by name; I thanked the production company, and the BBC. I threw in the usual line about being flustered by this overwhelming honour, and hoping I hadn’t forgotten to acknowledge anyone as a result, although I was pretty sure I hadn’t. I paused and gazed out at the audience for a moment. The final part was important; I needed to get it right.

‘The only people left to thank,’ I said, ‘are those I can’t name in public. I’m very happy to tell you that our brave colleague, Nadia, who gave and risked so much to help us, is safe and well. But there are others – some of them helping us undercover – who are still trapped in the repugnant trade that Nadia’s courage has helped to expose. This award is for her, and for them – the extraordinary people whose inspiring spirit never ceases to humble me, and who will not, I truly hope, need to remain nameless for much longer.’

I raised the award in a salute – dear god, it was heavy – and turned away. More applause, with some people cheering. I was acutely conscious of enjoying the warm glow of appreciation, even as I wanted to despise it. I wished I hadn’t said that stuff about being humbled. That must have sounded so fake.

I followed a man with headphones and a clipboard to the steps at the side of the stage, and trotted down them and wove my way back towards our table, through a gauntlet of congratulations – smiling faces, thumps on the back, handshakes.

As I neared our table I saw Maria coming towards me. I prepared myself for her embrace, but as she approached I saw concern in her expression. Without ceremony she elbowed aside a well-wisher, and grabbed my shoulder. She put her lips to my ear so she could be heard above the hubbub: ‘Come with me, something’s happened.’

She took my hand and began to lead me towards the back of the auditorium, past our own table. I stopped her before we reached the doors.

‘What is it?’

Maria held up my mobile phone. I’d left it with her when I went to the stage, having discovered that it spoiled the cut of my evening clothes when it was in my pocket.

‘It’s your mother,’ she said.

I looked at her in astonishment. ‘On the phone?’

Maria shook her head. She showed me the message on the screen.

I stared at it for a long time. ‘Oh god,’ I said, ‘she’s gone.’

The noise in the room around me became an abstract background, swelling and diminishing like waves crashing on a shoreline.

one

I gazed down into the swirling grey sea, keeping a firm grip on the railing as the tiny ferry bucked and plunged through the waves. The conditions had been described to me as bracing, rather than rough. If they were rough, I’d been told, I wouldn’t have been allowed on the deck.

Another burst of spray hit my face. I raised my head to shake it off, and for a moment I visualised Maria standing beside me at the rail, her dark hair being whipped by the wind, chin raised defiantly. Would she have enjoyed being out here? I had to admit I didn’t know, even after almost three years together. And now it didn’t matter.

We’d gone back to her place from the awards ceremony. She’d insisted that I shouldn’t be alone, and I didn’t want to tell her I would have preferred to go back to my own flat by myself. She sensed it, though. She was getting good at that.

We sat on Maria’s couch and she asked if I’d like to talk about my mother, and assured me she completely understood if I didn’t want to. All in good time, she said, and we could go straight to bed if I wanted to, and we could make love, or she would just hold me. Or not. Whatever worked for me.

‘Thanks,’ I said, and gazed at the floor.

She waited a moment, then stood up and left the room. Five minutes later she reappeared with a bottle of wine, poured two glasses, and sat down beside me again.

‘Did you expect it?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I hadn’t seen her for a while. We spoke on the phone about four months ago, but she didn’t say anything.’

‘Only seventy. That’s so young. And she didn’t tell you she was ill?’

‘She never told me anything. Nothing important, anyway.’

Maria took my hand. ‘I’m so sorry, darling.’

‘My mother liked to surprise people.’

She glanced at me with a frown, but relaxed when she saw I was smiling. I knew she found it hard to read my mood sometimes. That wasn’t her fault, especially at a moment like this, when I wasn’t sure of it myself. I wasn’t really feeling anything at all, to tell the truth, except a vague sense that something was over, like the end of a film or a concert. ‘It’s all right,’ I said, patting her knee, ‘don’t worry. We weren’t close.’

‘As you’ve mentioned before,’ Maria said, and refilled our glasses.

We went to bed not long afterwards, mostly because I couldn’t think of anything else to do. In the morning we had coffee together, then I left.

Four days later, I was sitting up in her bed, watching the patterns cast on the wall by the morning sunlight as the slender trees outside her window, dusted with green, swayed in a light breeze. I’d started to tell her about the inheritance, but now I was gazing at the play of shadows dappling the plasterwork.

Maria nudged me. ‘Go on.’

‘Sorry, I was miles away. Yes, it’s a huge house, apparently. Totally derelict.’

‘How much is it worth?’

‘It’s not clear. Like everything else about this whole fucking legacy. For one thing, it depends on whether anyone would want to buy it in its current condition. If not, is it worth restoring? I haven’t even seen pictures of it yet. Another thing that’s not entirely clear is whether or not I actually own the place.’

‘What do you mean? She left it to you! That what the lawyers said, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, but there are complications. Deeds, documents, god knows what. Stipulations and conditions. All kinds of paperwork that has to be verified. If it can even be found.’

‘What a pain.’

‘Tell me about it. But if I can get all that stuff straightened out, maybe someone will want to buy it from me. I mean, certain people might find it an attractive proposition, don’t you think? Romantic, even. A huge mansion on a remote Scottish island with a small population. All very quiet, and out of the way. There’s even a lake next to the house. It all sounds like Brigadoon, or something.’

‘Like what?’

‘That film. Brigadoon. The musical. About a magical place that comes out of the mist every hundred years.’

‘Oh, I remember! We saw it one night when we were stoned.’

‘That’s right. It was funny.’

Maria was silent for a moment, then she said, ‘Maybe you should go there.’

‘Really? You think so?’

We were both naked, and I gazed at her, running my eyes appreciatively over her body. She smiled and rolled over to nestle against me. I put my arm around her, glad I didn’t now have to face her. She’d said precisely what I’d wanted her to say.

She began to stroke my chest. ‘You could use a break, couldn’t you?’

‘Could I?’

‘I think so. That last film took it out of you. And the one before.’

‘I wasn’t undercover for the care home thing. Just a lot of editing.’

‘Right. Sitting and watching that horrible footage over and over again. That’s probably even worse. A month of your life, every day, seeing those poor, helpless people being abused and tormented. Don’t tell me that doesn’t affect you.’

‘It did, I suppose.’

I thought about the footage she was referring to. It was certainly distressing to watch, and occasionally during the editing process I got a weird urge to wash my hands, despite having no physical contact with material which, by this stage, existed only as digital code. But had I been traumatised? I didn’t think so. I remembered a medic I’d met in Afghanistan, an older guy who’d worked in a children’s hospice for a few years. He told me he was able to get through his shift – which often included comforting dying kids, and dealing with their families – and remain composed. Then he’d go home, watch an episode of ER, and cry his eyes out. I found that interesting. He said it didn’t have to be ER, it could be any medical show – Casualty, House, or even Scrubs – just so long as it involved doctors, doing their work. I understood what that was all about. But nothing like it had happened with me.

‘Believe me,’ Maria continued, ‘it affected you. And then you went straight into the trafficking film, with all the tension, and getting hit, and then the award, and now this news about your mother. I think you’re burned out, Adam.’

‘Yeah? I don’t feel burned out.’

‘You’d be the last to know.’

I gazed at the shadows on the wall again, letting her see I was thinking about it.

‘Go and take a look at the place,’ Maria said, ‘as part of a way to sort it out. And at the same time, use it as an excuse to get away from everything. Have a complete break.’

‘Maybe I will,’ I murmured. ‘You’re right. I need to get away.’

‘We could go together.’

I didn’t reply, but I knew she felt the little spasm of tension that twitched through my arm.

She rolled off me and propped herself up on her elbow. ‘What?’

‘Nothing.’

‘You don’t want me to come?’

‘I didn’t realise that’s what you meant.’

‘What did you think I meant?’

‘That I should…you know, just get away. Have some time on my own.’

‘Is that what you want?’

‘I don’t know. But when you just suggested it a minute ago I suddenly thought, yes, maybe that’s what I should do. It struck a chord. And it made me think of just being somewhere else, with a chance to recharge my batteries.’

‘And you can’t do that with me?’

‘I’m not saying that.’

She gave me a long, deadpan look.

‘What?’ I said.

‘I’m going to get some coffee.’

She was gone a long time. When she came back she’d showered and put on her thick bathrobe and wound a towel around her hair. She stood in the doorway. I raised the sheet so she could get back into bed, but she didn’t move. I let it fall and met her gaze.

She looked away after a moment, and went to sit at her dressing table where she began to towel her hair, her eyes flashing at me in the mirror every so often.

I wondered how long this would take. ‘Are you all right?’ I said.

‘Fine. I was just thinking.’

‘Thinking what?’

‘Maybe I’ll take a holiday by myself, if I can’t come with you. I could go on a romantic cruise for singles.’

‘I didn’t say you couldn’t come with me.’

‘You didn’t have to.’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘I’m sorry. Please come with me.’

She slung the towel around her shoulders, grasping the ends like a prize fighter, and took a deep breath and swivelled around to face me. Here it came.

‘You planned this,’ she said, ‘didn’t you?’

‘Planned what?’

‘So it would be my idea, as if it never crossed your mind that we could go together, and now it makes me look like I’m being pushy and needy if I say I want to come too.’

‘Where do you get all that from?’

‘This is the way it works, isn’t it? You’re the one who’s always leaving, and I wait here doing nothing, then you come back for as long as you want, but never long enough to commit to anything; god forbid, oh no, that would be too restricting, too much of a burden on your wild, noble, free spirit, wouldn’t it?’

‘You don’t do nothing,’ I said. ‘You’ve got your work.’

‘Oh, fuck off. In fact, really fuck off.’ She stood up. ‘Go on, go away and don’t come back. Go and find someone else to rescue, before you get bored with me again. I’ll be in the kitchen until you’ve gone. Leave your keys on the hall table.’

She draped the towel over her head like a hood, and walked out.

***

I looked down at the sea again and got a face full of spray for my trouble. As I raised my head and wiped my face I saw a low, dark mass on the horizon, dead ahead. I looked up and tried to catch Archie’s eye, but the old man’s gaze was focused on our destination, both hands on the wheel in front of him.

I took three unsteady steps away from the side and lurched for the handrail of the metal stairway up to the wheelhouse. The boat was no more than forty feet long, and the entire rear deck was occupied by a battered old Land Rover that was held in place by a couple of frayed ropes – not very securely, in my estimation.

As I entered the wheelhouse Archie glanced over his shoulder and nodded to me, then returned his attention to the horizon. He jerked his chin at the island that was now clearly visible ahead of us. ‘Your first time over there, you said?’

‘That’s right.’ I shuffled forward and stood beside him. I watched the way his hands seemed to move on the wheel intuitively, appearing to both steer and respond to the vessel at the same time.

Archie noticed me looking at his hands. He took them both off the wheel, which spun crazily. He raised a shaggy eyebrow at me. ‘Steers herself, you see,’ he said.

‘I’ll take your word for it.’

He grunted and took the wheel again.

He was almost too good to be true. If you asked a casting agency to provide you with someone to play the part of a grizzled old Scottish sea-dog you would have rejected Archie as being too obviously a stereotype. It was all there: the weather-beaten face, the wild red hair escaping from beneath a battered oilskin hat, the bushy beard in various shades of orange, grey and white. The man even had a pipe jammed between his teeth.

‘So,’ he said, ‘you’re the lad who’s coming to take over the place by the loch.’

‘I don’t know about taking it over. My mother died, and–’

‘Sorry for your loss,’ he interjected. ‘Her troubles are over. It comes to us all.’

I glanced at him. He was old-school, all right. Old Testament, even. ‘Anyway,’ I continued, ‘it was only when she died that I discovered she seemed to have owned this place, this house, Stone Heart Deep.’

‘Stone Heart Deep?’

‘Isn’t that what it’s called?’

Archie gave me a flinty glance from beneath knitted brows. ‘That’s what the loch is called,’ he said. ‘But folks around there have another name for it.’

‘What do they call it?’

He squinted into the distance again. ‘I wouldn’t know,’ he muttered, ‘I’m not from around there.’

I stared at the old man’s craggy profile. I saw a fractional twitch at the side of his mouth, and heard an odd, rhythmic groaning sound leaking out from beside his pipe. I realised he was chuckling. The old bastard was fucking with me. I laughed. ‘You had me there for a moment.’

Archie glanced at me again. ‘Lighten up, man. Chill.’

‘Right. It’s just that I don’t know what to expect. On the island there.’

Ahead of us, our destination was beginning to define itself as a formidable mass of rock, utterly isolated in a vast expanse of sea and sky.

‘Well, don’t expect any fishing,’ he said. ‘Too much peat in the water. That loch where your house lies is like a bog.’

‘It may not actually be my house. My mother left her affairs in some disorder.’

‘Aye, that doesn’t surprise me.’

I felt abruptly wrong-footed. I turned sharply to him. ‘Why not?’

‘I met her once or twice.’

‘Really? She said she was only on the island for a short time. Before I was born.’

‘Did she, now? Yes, I dare say that’s right. I didn’t know her at all well.’

‘I don’t think anyone did,’ I said, and immediately regretted it. Too much information. I cleared my throat. ‘The thing is, she used to talk about a strange old house on a remote island, but I always assumed it was just one of her stories. I didn’t even know if the island was real, to tell you the truth.’

‘Oh, it’s real enough,’ Archie said, ‘as you can see. But I wouldn’t want to live there myself, all the same.’

‘Why not?’

‘That whole place is too damn quiet. You sneeze, and it’s news for a month. I like a bit of salt in my porridge.’ He winked. ‘I’m not dead yet, man.’

I liked Archie. I smiled, and when I turned to look at the island again I was startled because it suddenly seemed much closer. I could see a little harbour nestled among a cluster of cottages, and make out a man with a dog, waiting on the quayside.

two

I stood with my bag bedside me at the top of a concrete jetty that sloped down to the water, watching as Archie reversed the Land Rover up to the quay. The man with the dog walked slowly backwards up the slope, guiding Archie with hand-signals, which the old man ignored. As the vehicle drew level with me, Archie leaned out of the window and said, ‘You’re staying at the pub up in town, I understand.’

‘That’s right.’

‘I’d give you a ride, but you’re expected to take the taxi.’

‘Expected?’

‘Correct. Otherwise the taxi fellow might be offended.’ He cocked an eyebrow at the man with the dog, who was now standing beside me. ‘Isn’t that right, Ogden?’

‘Oh yes, Archie, we must not deprive the poor wee man of his trade.’

Archie laughed. He raised a hand in farewell to me, and swung the Land Rover around in a tight circle. He gunned the engine, and the vehicle rattled away along the cobbles, exhaust belching.

The man beside me stepped forward and extended his hand. He was big and fleshy and he looked about fifty, but he had a boyish air, accentuated by a peaked cap perched jauntily on a mass of curls. The cap had a brass plate on the front that declared him to be the Harbour Master. His dog – a border collie, which looked as though it came from a disreputable branch of the family, more likely to rustle sheep than to herd them – lay at his feet, eyeing me warily.

‘I’m Ogden,’ the man said. ‘Good day, and how do you do?’

I took the proffered hand. ‘I’m Adam.’

‘I know that,’ Ogden said, pumping my hand vigorously and smiling at me. I smiled back. Ogden released my hand. He continued to smile, showing no sign of intending to do anything else for the foreseeable future.

‘So,’ I said finally, ‘is the man with the taxi around?’

‘Indeed he is. He will be with you momentarily.’

He removed his cap, and whistled. The dog at his feet sprang up and raced towards a row of cottages on the far side of the cobbled road lining the quayside, heading for an open door at end of the row. He threw his cap towards the dog, spinning it like a Frisbee. Without looking around, the dog leaped up, twisting in the air to catch the cap in its teeth, and disappeared into the cottage with it.

I glanced at Ogden, whose placid smile was inscrutable. After a few seconds the dog emerged from the cottage with a different cap between its teeth, ran up to Ogden, and sat on its haunches in front of him.

‘Good lad,’ Ogden said, and took the cap. He placed it carefully on his head and turned to me. ‘Here he is.’

He raised a finger to the peak of the new cap in a salute, turned on his heel, and waddled briskly to a garage next to his cottage. He flung open the doors with a flourish to reveal an elderly but immaculate black London taxi.

I twisted around in the back seat of the taxi and looked down at the little harbour as the car began to climb a steep hill. The ferry bobbing at the end of the jetty seemed like a child’s toy, washed up by the wide, endless sea beyond it. I could just make out Ogden’s dog, prowling around in front of the cottages, on patrol.

‘How long will the ferry stay there?’ I said.

He glanced over his shoulder at me. ‘Archie takes her back tomorrow. Twice a week he comes over and delivers supplies to folk. Weather permitting, of course.’

‘Is it sometimes too rough?’

‘Oh, indeed. And for bigger ships than Archie’s, believe me. On occasion we have to wait several days before anything can reach us, especially in winter.’

‘How do you manage?’

‘How we’ve always managed. We tighten our belts when we need to.’ He turned the wheel sharply and took a hairpin bend. The road was getting steeper.

‘Do you like being so cut off?’ I said.

He chuckled. ‘Depends what you mean. We’re not cut off from each other.’

‘Right. But from the mainland?’

‘We do well enough. We always have, and I expect we always will.’ He swung the wheel again as he took another sharp bend. He wasn’t slowing down for the turns, and this time the back of the car fishtailed slightly before he corrected it. When we’d set off, I noticed that Ogden seemed unconcerned about which side of the road he occupied, and as it got steeper and narrower the question became increasingly irrelevant. There was barely room for a single vehicle, let alone any oncoming traffic.

‘Aye, we’ve always managed somehow,’ he continued, turning around for a moment to grin at me, which didn’t improve his driving.

‘But it must get lonely sometimes,’ I said, ‘being so remote.’

‘We’re not bothered by it.’ He squinted at me in the rear-view mirror. ‘How much do you know about the history of this place?’

‘Not much. I looked online, but I can’t claim to have done much research.’

Ogden chuckled again. ‘Oh yes, research. You’re a newsman, after all.’

‘How did you know that?’

‘Archie told me. And people have been researching this place for thousands of years, it’s just that in the old days they arrived in longboats and did their research with swords and spears and suchlike.’

I tried to remember whether I’d told Archie I was a journalist, but I was distracted by Ogden twisting around again to speak to me. I found myself tensing my leg, pressing an imaginary brake pedal.

‘Now, that was Tallog Bay we’ve just left,’ he said, assuming the tone of a tour guide, and nodding at the road behind us, ‘and it used to be the main settlement, many hundreds of years ago.’ He turned back to face the road ahead. ‘But as you could surely see,’ he continued, ‘it is very exposed, and not just to the elements. However, it was a somewhat bigger place before folk moved up to the higher ground inland. This part of the island was more populated back then. Look over on your right-hand side there.’

I glimpsed a cluster of ruined crofts on a barren slope we were passing. Most of them were little more than piles of stones, overgrown with tough looking bracken.

‘Why did people move inland?’ I said.

‘Pirates, Vikings, ruffians of every kidney. At first, the natives only used to go inland to hide up there, and they’d come back down when all the hooligans had gone home. But each time they ran inland they made their hidey-holes a wee bit more comfortable and cosy until eventually some lazy buggers couldn’t be arsed to come back down again at all, and so Creedish up there became a town of itself.’

‘That’s civilisation for you,’ I said.

‘Oh, it’s reasonably civilised, but it’s not much of a town, to tell the truth, it’s more of an oversized village. But it’s where you’ll find who you have come to see.’

After a pause I said, ‘And who have I come to see?’

‘The lawyer, Mrs Baird. To sort out all the bother with your house.’

I frowned at the back of Ogden’s head, imagining that my displeasure could penetrate it like a kind of radiation, and make his brain itch. Attempting a tone of chilly courtesy I said, ‘Does everyone here know my business?’

‘Oh yes,’ he replied cheerfully. Abruptly he leaned away from the wheel and peered up out of the passenger-side window. ‘Ah, now this is interesting,’ he said. ‘You see those stones up there?’

He pointed to a windswept hill with a jagged ring of standing-stones encircling the top, looming against the slate-grey sky. The effect was bleak and unwelcoming. Perhaps that was the intention, I thought.

‘Now, here’s a mystery for you,’ he said, accelerating into an oncoming bend and glancing around to look at me, an excited gleam in his eye. ‘That hill is an Iron Age fort dating from a later period than the stones, which means they must have bee–’

He saw my expression change and whirled around to face the road. Too late.

An old woman on a bicycle had appeared from around the blind curve. Ogden slammed on the brakes in the same instant that the front of the car hit the bike. The woman’s body flew into the air and struck the windscreen with a sickening thud before bouncing off to one side as the bicycle smashed onto the roof and cartwheeled away.