Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ozymandias Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

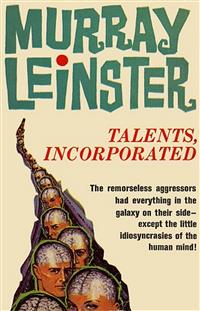

Bors felt as if he'd been hit over the head. This was ridiculous! He'd planned and carried out the destruction of that warship because the information of its existence and location was verified by a magnetometer...Murray Leinster weaves a science fiction masterpiece with Talents, Inc.!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 252

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Talents, Inc.

Murray Leinster

OZYMANDIAS PRESS

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy this book, please leave a review or connect with the author.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2016 by Murray Leinster

Interior design by Pronoun

Distribution by Pronoun

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 1

YOUNG CAPTAIN BORS—WHO IMPATIENTLY refused to be called anything else—was strangely occupied when the communicator buzzed. He’d ripped away the cord about a thick parcel of documents and heaved them into the fireplace of the office of the Minister for Diplomatic Affairs. A fire burned there, and already there were many ashes. The carpet and the chairs of the cabinet officer’s sanctum were coated with fine white dust. As the communicator buzzed again, Captain Bors took a fireplace tool and stirred the close-packed papers to looseness. They caught and burned instead of only smouldering.

The communicator buzzed yet again. He brushed off his hands and pressed the answer-stud.

He said bleakly: “Diplomatic Affairs. Bors speaking.”

The communicator relayed a voice from somewhere else with an astonishing fidelity of tone.

“Spaceport, sir. A ship just broke out of overdrive. We don’t identify its type. One ship only, sir.“

Bors said grimly;

“You’d recognize a liner. If it’s a ship from the Mekinese fleet and stays alone, it could be coming to receive our surrender. In that case play for time and notify me.”

“Yes, sir.—One moment! It’s calling, sir! Here it is—.“

There was a clicking, and then there came a voice which had the curious quality of a loudspeaker sound picked up and relayed through another loudspeaker.

“Calling ground! Calling ground! Space-yacht Sylva reports arrival and asks coordinates for landing. Our mass is two hundred tons standard. Purpose of visit, pleasure-travel.“

A pause. The voice from the spaceport:

“Sir?“

Captain Bors said impatiently, “Oh, let him down and see if he knows anything about the Mekinese. Then advise him to go away at once. Tell him why.”

“Yes, sir.“

A click. Young Captain Bors returned to his task of burning papers. These were the confidential records of the Ministry for Diplomatic Affairs. Captain Bors wore the full-dress uniform of the space navy of the planet Kandar. It was still neatly pressed but was now smudged with soot and smeared with ashes. He had burned a great many papers today. Elsewhere in the Ministry other men were burning other documents. The other papers were important enough; they were confidential reports from volunteer- and paid-agents on twenty planets. In the hands of ill-disposed persons, they could bring about disaster and confusion and interplanetary tension. But the ones Captain Bors made sure of were deadly.

He burned papers telling of conditions on Mekin itself. The authors of such memoranda would be savagely punished if they were found out. Then there were papers telling of events on Tralee. If it could be said that he were more painstakingly destructive than average about anything, Captain Bors was about them. He saw to it that they burned to ashes. He crushed the ashes. He stirred them. It would be unthinkable that such morsels could ever be pieced together and their contents even guessed at.

He went on with the work. His jaunty uniform became more smeared and smudged. He gave himself no rest. There were papers from other planets now under the hegemony of Mekin. Some were memoranda from citizens of this planet, who had traveled upon the worlds which Mekin dominated as it was about to dominate Kandar. They, especially had to be pulverized. Every confidential document in the Ministry for Diplomatic Affairs was in the process of destruction, but Captain Bors in person destroyed those which would cause most suffering if read by the wrong persons.

In other ministries and other places similar holocausts were under way. There was practically nothing going on on Kandar which was not related to the disaster for which the people of that world waited. The feel of bitterness and despair was everywhere. Broadcasting stations stayed on the air only to report monotonously that the tragic event had not yet happened. The small space-navy of Kandar waited, aground, to take the king and some other persons on board at the last moment. When the Mekinese navy arrived—or as much of it as was needed to make resistance hopeless—the end for Kandar would have come. That was the impending disaster. If it came too soon, Bors’s task of destruction couldn’t be completed as was wished. In such a case this Ministry and all the others would hastily be doused with incendiary material and fired, and it would desperately be hoped that all the planet’s records went up in the flames.

Captain Bors flung more and more papers on the blaze. He came to an end of them.

The communicator buzzed, again. He answered once more.

“Sir, the space-yacht Sylva is landed. It comes from Norden and has no direct information about the Mekinese. But there’s a man named Morgan with a very important letter for the Minister for Diplomatic Affairs. It’s from the Minister for Diplomatic Affairs on Norden.“

Bors said sardonically, “Maybe he should wait a few days or hours and give it to the Mekinese! Send him over if he wants to take the chance, but warn him not to let anybody from his yacht leave the spaceport!”

“Yes, sir.“

Bors made a quick circuit of the Ministry building to make sure the rest of the destruction was thoroughly carried out. He glanced out of a window and saw the other ministries. From their chimneys thick smoke poured out—the criminal records were being incinerated in the Ministry of Police. Tax records were burning in the Ministry of Finance. Educational information about Kandarian citizens flamed and smoked in the Ministry of Education. Even voting and vehicle-registry lists were being wiped out of existence by flames and the crushing of ashes at appropriate agencies. The planet’s banks were completing the distribution of coin and currency, with promissory notes to those depositors they could not pay in full, and the real-estate registers were open so individuals could remove and hide or destroy their titles to property. The stockholders’ books of corporations were being burned. Small ships parted with their wares and took promises of payment in return. The planet Kandar, in fact, made ready to receive its conquerors.

It was not conquered yet, but there could be no hope.

Bors was in the act of brushing off his hands again, in a sort of symbolic gesture of completion, when a ground-car stopped before the Ministry. A stout man got out. A rather startlingly pretty girl followed. They advanced to the door of the Ministry.

Presently, Captain Bors received the two visitors. His once-jaunty uniform looked like a dustman’s. He was much more grim than anybody his age should ever be.

“Your name is Morgan,” he said formidably to the stout man. “You have a letter for the Minister. He’s not here. He’s gathering up his family. If anyone’s in charge, I am.”

The stout man cheerfully handed over a very official envelope.

Bors said caustically, “I don’t ask you to sit down because everything’s covered with ash-dust. Excuse me.”

He tore open the envelope and read its contents. His impatience increased.

“In normal times,” he said, “I’m sure this would be most interesting. But these are not normal times. I’m afraid—”

“I know! I know!” said the stout man exuberantly. “If times were normal I wouldn’t be here! I’m president and executive director of Talents, Incorporated. From that letter you’ll see that we’ve done very remarkable things for different governments and businesses. I’d like to talk to someone with the authority to make a policy decision. I want to show what we can do for you.”

“It’s too late to do anything for us,” said Bors. “Much too late. We expect the Mekinese fleet at any instant. You’d better go back to the spaceport and take off in your yacht. They’re going to take over this planet after a slight tumult we expect to arrange. You won’t want to be here when they come.”

Morgan waved a hand negligently.

“They won’t arrive for four days,” he said confidently. “That’s Talents, Incorporated information. You can depend on it! There’s plenty of time to prepare before they get here!” He smiled, as if at a joke.

Young Captain Bors was not impressed. He and all the other officers of the Kandarian defense forces had searched desperately for something that could be done to avert the catastrophe before them. They’d failed to find even the promise of a hope. He couldn’t be encouraged by the confidence of a total stranger,—and a civilian to boot. He’d taken refuge in anger.

The pretty girl said suddenly, “Captain, at least we can reassure you on one thing. Your government chartered four big liners to remove government officials and citizens who’ll be on the Mekinese black list. You’re worried for fear they won’t get here in time. But my father—”

The stout man looked at his watch.

“Ah, yes! You don’t want the fleet cluttered up with civilians when it takes to space! I’m happy to tell you it won’t be. The first of your four liners will break out of overdrive in—hm—three minutes, twenty seconds. Two others will arrive tomorrow, one at ten minutes after noon, the other three hours later. The last will arrive the day after, at about sunrise here.”

Bors went a trifle pale.

“I doubt it. It’s supposed to be a military secret that such ships are on the way. Since you know it, I assume that the Mekinese do, too. In effect, you seem to be a Mekinese spy. But you can hardly do any more harm! I advise you to go back to your yacht and leave Kandar immediately. If our citizens find out you are spies, they will literally tear you to pieces.”

He looked at them icily. The stout man grinned.

“Listen, your h— Captain, listen to me! The first liner will report inside of five minutes. That’ll be a test. Here’s another. There’s a Mekinese heavy cruiser aground on Kandar right now! It’s on the sea bottom fifty fathoms down, five miles magnetic north-north-east from Cape Farnell! You can check that! The cruiser’s down there to lob a fusion bomb into your space-fleet when it starts to take off for the flight you’re planning—to get all the important men on Kandar in one smash! That’s Talents, Incorporated information! It’s a free sample. You can verify it without it costing you anything, and when you want more and better information—why—we’ll be at the spaceport ready to give it to you. And you will want to call on us! That’s Talents, Incorporated information, too!”

He turned and marched confidently—almost grandly—out of the room. The girl smiled faintly at Bors.

“He left out something, Captain. That cruiser— It could hardly act without information on when to act. So there’s a pair of spies in a little shack on the cape. They’ve got an underwater cable going under the sand beach and out and down to the space-cruiser. They’re watching the fleet on the ground with telescopes. When they see activity around it, they’ll tell the cruiser what to do.” Then she smiled more broadly. “Honestly, it’s true! And don’t forget about the liner!”

She followed her father out of the room. Outside, as they got into the waiting ground-car, she said to her father, “If he smiled, I think I’d like him.”

But Bors did not know that at the time. He would probably not have paid any attention if he had. Kandar was about to be taken over by the Mekinese, as his own Tralee had been ten years before, and other planets before that. Mekin was making an empire after an ancient tradition, which scorned the idea of incorporating other worlds into its own governmental system—which was appalling—but merely made them subjects and satellites and tributaries.

Bors had been born on Tralee, which he remembered as a tranquil world of glamor and happiness. But he was on Kandar now. He served in its space-navy, and he foresaw Kandar becoming what Tralee had become. He felt such hatred and rebellion toward Mekin, that he could not notice a pretty girl. He was getting ready for the savage last battle of the space-fleet of Kandar, which would fight in the great void until it was annihilated. There was nothing else to do if one was not to submit to the arrogant tyranny that already lorded it over twenty-two subject planets and might extend itself indefinitely throughout the galaxy.

He moved to verify again the complete pulverizing of the ashes in the fireplace.

The communicator buzzed. He pressed the answer button. A voice said, “Sir, the space-liner Vestis reports breakout from overdrive. Now driving for port. Message ends.“

Bors’s eyes popped wide. He’d heard exactly that only minutes ago! It could be coincidence, but it was a very remarkable one. The man Morgan had come to him to tell him that. If he’d come for some other reason, and merely made a guess, it could be coincidence. But he’d come only to tell Bors that he could be useful! And it was impossible, at a destination-port, to know when a ship would break out of overdrive! Einstein’s data on the anomalies of time at speeds near that of light naturally did not apply to overdrive speeds above it. Nobody could conceivably predict when a ship from many light-years away would arrive! But Morgan had! It was impossible!

He’d said something else that was impossible, too. He’d said there was a Mekinese cruiser on the sea-floor of Kandar, where it could blast all the local fleet—which was ready to fight but vulnerable to a single fusion-bomb. If such a thing happened, the impending disaster would be worse than intolerable. To Bors it would mean dying without a chance to strike even the most futile of blows at the enemy.

He hesitated a long minute. Morgan’s errand had been to make a prediction and give a warning, to gain credence for what he could do later. The prediction was fulfilled. But the warning....

An enemy cruiser in ambush on Kandar was a possibility that simply hadn’t been considered—hadn’t even occurred to anyone. But once it was mentioned it seemed horribly likely. There was no time for a search at random, but if Morgan had been right about one thing he might have some way to know about another.

Bors gave curt orders to his subordinates in the work of record-destruction. He went out of the building to the greensward mall that lay between the ministries of the government, and headed for the palace at its end. The government of Kandar was not one of great pomp and display. There was a king, to be sure, but nobody could imagine the perspiringly earnest King Humphrey the Eighth as a tyrant. There were titles, it was true, but they were life appointments to the planet’s legislative Upper House. Kandar was a tranquil, quaint, and very happy world. There were few industries, and those were small. Nobody was unduly rich, and most of its people were contented. It was a world with no history of bloodshed—until now.

Bors brushed absently at his uniform as he walked the two hundred yards to the palace. He abstractedly acknowledged the sentries’ salutes as he entered. Much of the palace guard had been sent away, and most of the palace’s small staff would hide from the Mekinese. The aggressors had a nasty habit of imposing special humiliations upon citizens who’d been prominent before they were conquered.

He went unannounced into King Humphrey’s study, where the monarch conferred dispiritedly with Captain Bors’s uncle, the exiled Pretender of Tralee, who listened with interest. The king was talking doggedly to his old friend.

“No. You’re mistaken. You’ll have my written order to distribute the bullion in the Treasury to all the cities, to be shared as evenly as possible by all the people. The Mekinese can’t blame you for obeying an order of your lawful king before they unlawfully seize the kingdom!”

Captain Bors said curtly, “Majesty, the first of the four liners is in. Two more will arrive tomorrow and the last at sunrise the day after. The Mekinese will be here two days later.”

King Humphrey and Captain Bors’s uncle stared at him.

“And,” said Bors, “the same source of information says there’s a Mekinese cruiser waiting underwater off Cape Farnell to lob a fusion bomb at the fleet as it’s ready to lift.”

King Humphrey said, “But nobody can possibly know that two liners will come tomorrow! One hopes so, of course. But one can’t know! As for a cruiser, submerged, there’s been no report of it.”

“The information,” said Captain Bors, “came from Talents, Incorporated. It’s sample information, given free. The first item has checked. He came with a letter from a cabinet minister on Norden.”

Bors handed it to the Pretender of Tralee.

“Mmmm,” he said thoughtfully. “I’ve heard of this Talents, Incorporated. And on Norden, too! Phillip of Norden mentioned it to me. A man named Morgan had told him that Talents, Incorporated had secured information that an atom bomb—a fission bomb as I remember, and quite small—had been set to assassinate him as he laid a cornerstone. The information turned out to be correct. Phillip of Norden and some thousands of his subjects would have been killed. The assassins were really going to extremes. As I remember, Morgan wouldn’t accept money for the warning. He didaccept a medal.”

“I think,” said Bors, “I think I shall investigate what he said about a Mekinese ship in hiding. You’ve no objection, Majesty?”

King Humphrey the Eighth looked at the Pretender. One was remarkably unlike the other. The King was short and stocky and resolute, as if to overcome his own shortcomings. The pretender was lean and gray, with the mild look of a man who has schooled himself to patience under frustration. He nodded. King Humphrey shook his head.

“Very well,” said Bors. “I’ll borrow a flier and see about it.”

He left the palace. There was already disorganization everywhere. The planetary government was in process of destroying all the machinery by which Kandar had been governed, as if to make the Mekinese improvise a government anew. They would make many blunders, of course, which would be resented by their new subjects. There would be much fumbling, which would keep the victims of their conquest from regarding them with respect. And there would be the small tumult Bors had said was in preparation. The king and the Kandarian fleet would fight, quite hopelessly and to their own annihilation, when the Mekinese fleet appeared. It would be something Kandar would always remember. It was likely that she would not be the most docile of the worlds conquered by Mekin. The Mekinese would always and everywhere be resented. But on Kandar they would also be despised.

Bors found the ground-cars which waited to carry the king and those who would accompany him, to the fleet when the time came. He commandeered a ground-car and a driver. He ordered himself driven to the atmosphere-flier base of the fleet.

On the way the driver spoke apologetically. “Captain, sir, I’d like to say something.”

“Say it,” said Bors.

“I’m sorry, sir, but I’ve got a wife and children. Even for their sakes, sir. I mean, if it wasn’t for them I’d—I’d be going with the fleet. I—wanted to explain—”

“Why you’re staying alive?” asked Bors. “You shouldn’t feel apologetic. Getting killed in the fleet ought to follow at least the killing of a few Mekinese. There should be some satisfaction in that! But if you stay here your troubles still won’t be over, and there’ll be very little satisfaction in what you’ll go through. What the fleet will do will be dramatic. What you’ll do won’t. You’ll have the less satisfying role. I think the fleet is taking the easy way out.”

The driver was silent for a long time as he drove along the strangely unfrequented highways. Just before the ground-car reached the air base, he said awkwardly, “Thank you, sir.”

When he brought the car to a stop, he got out quickly to offer a very stiff military salute.

Bors went inside. He found men with burning eyes conferring feverishly. An air force colonel said urgently, “Sir, please advise us! We have our orders, but there’s nearly a mutiny. We don’t want to turn anything over to the Mekinese—after all, no matter what the king has commanded, once the fleet had lifted off, there can be no punishment if we destroy our planes and blast our equipment! Will you give us an unofficial—”

Bors broke in quickly.

“I may be able to give you a chance at a Mekinese cruiser. Can you lend me a plane with civilian markings and a pilot who’s a good photographer? I’ll need a magnetometer to trail, too. There’s a rather urgent situation coming up.”

The men stared at him.

He explained the possibility of a Mekinese space-cruiser lying in fifty fathoms off Cape Farnell. He did not say where the information came from. Even to men as desperate as these, Talents, Incorporated information would not seem credible without painstaking explanation. Bors was by no means sure that he believed it himself, but he wanted to so fiercely that he sounded as if some Mekinese spy or traitor had confessed it.

The feeling of tenseness multiplied, but voices grew very quiet. No man spoke an unnecessary word. In minutes they had made complete arrangements.

When the atmosphere-flier took off down the runway, wholly deceptive explanations were already being made. It was said that the atmosphere-fliers were to load bombs for demolition because the king was being asked for permission to bomb all mines and bridges and railways and docks that would make Kandar a valuable addition to the Mekinese empire. Everything was to be destroyed before the conquerors came to ground. The destruction would bring hardship to the citizens—so the story admitted—but the Mekinese would bring that anyhow. And they shouldn’t profit by what Kandar’s people had built for themselves.

The point was, of course, to get bombloads aboard planes with no chance of suspicion by spy or traitor of the actual use intended for them. Meanwhile, Bors flew in an atmosphere-flier which looked like a private ship and explained his intentions to the pilot, so that the small plane did not go directly to the spot five miles offshore that the mysterious visitors had mentioned, to make an examination of the sea bottom. Instead, it flew southward. It did not swing out to sea for nearly fifty miles. It went out until it was on a line between a certain small island where many well-to-do people had homes, and the airport of the planet’s capital city. Then it headed for that airport.

It flew slowly, as civilian planes do. By the time the sandy beaches of a cape appeared, it was quite convincingly a private plane bringing someone from a residential island to the airport of Kandar City. If a small object trailed below it, barely above the waves, suspended by the thinnest of wires, it was invisible. If the plane happened to be on a course that would pass above a spot north-northeast from the tip of the cape, a spot calculated from information given by Talents, Incorporated, it seemed entirely coincidental. Nobody could have suspected anything unusual; certainly nothing likely to upset the plans of a murderous totalitarian enemy. One small and insignificant civilian plane shouldn’t be able to prevent the murder of a space-fleet, a king and the most resolute members of a planet’s population!

Captain Bors flew the ship. The official pilot used an electron camera, giving a complete and overlapping series of pictures of the shore five miles away with incredible magnification and detail.

The magnetometer-needle flicked over. Its findings were recorded. As the plane went on it returned to a normal reading for fifty fathoms of seawater.

Half an hour later the seemingly private plane landed at the capital airport. Another half-hour, and its record and pictures were back at the air base, being examined and computed by hungry-eyed men.

Just as the pretty Morgan girl had said, there was a shack on the very tip of the cape. It was occupied by two men. They loafed. And only an electron camera could have used enough magnification to show one man laughing, as if at something the other had said. The camera proved—from five miles away—that there was no sadness afflicting them. One man laughed uproariously. But the rest of the planet was in no mood for laughter.

The magnetometer recording showed that a very large mass of magnetic material lay on the ocean bottom, fifty fathoms down. Minute modifications of the magnetic-intensity curve showed that there was electronic machinery in operation down below.

Bors made no report to the palace. King Humphrey was a conscientious and doggedly resolute monarch, but he was not an imaginative one. He would want to hold a cabinet meeting before he issued orders for the destruction of a space-ship that was only technically and not actually an enemy. Kandar had received an ultimatum from Mekin. An answer was required when a Mekinese fleet arrived off Kandar. Until that moment there was, in theory, no war. But, in fact, Kandar was already conquered in every respect except the landing of Mekinese on its surface. King Humphrey, however, would want to observe all the rules. And there might not be time.

The air force agreed with Bors. So squadron after squadron took off from the airfield, on courses which had certain things in common. None of them would pass over a fisherman’s shack on Cape Farnell. None could pass over a spot five miles north-north-east magnetic from that cape’s tip, where the bottom was fifty fathoms down and a suspicious magnetic condition obtained. One more thing unified the flying squadrons: At a given instant, all of them could turn and dive toward that fifty-fathom depth at sea, and they would arrive in swift and orderly succession. This last arrangement was a brilliant piece of staff-work. Men had worked with impassioned dedication to bring it about.

But only these men knew. There was no sign anywhere of anything more remarkable than winged squadrons sweeping in a seemingly routine exercise about the heavens. Even so they were not visible from the cape. The horizon hid them.

For a long time there was only blueness overhead, and the salt smell of the sea, and now and again flights of small birds which had no memory of the flight of their ancestors from ancient Earth. The planet Kandar rolled grandly in space, awaiting its destiny. The sun shone, the sun set; in another place it was midnight and at still another it was early dawn.

But from the high blue sky near the planet’s capital, there came a stuttering as of a motor going bad. If anyone looked, a most minute angular dot could be seen to be fighting to get back over the land from where it had first appeared, far out at sea. There were moments when the stuttering ceased, and the engine ran with a smooth hum. Then another stutter.

The plane lost altitude. It was clear that its pilot fought to make solid ground before it crashed. Twice it seemed definitely lost. But each time, at the last instant, the motor purred—and popped—and the plane rose valiantly.

Then there was a detonation. The plane staggered. Its pilot fought and fought, but his craft had no power at all. It came down fluttering, with the pilot gaining every imaginable inch toward the sandy shore. It seemed certain that he would come down on the white beach unharmed, a good half-mile from the fisherman’s shack on the cape. But—perhaps it was a gust of wind. It may have been something more premeditated. One wing flew wildly up. The flier seemed to plunge crazily groundward. At the last fraction of a second, the plane reeled again and crashed into the fisherman’s shack before which, from a distance of five miles, a man had been photographed, laughing.

Timbers splintered. Glass broke musically. Then there were thuds as men leaped swiftly from the plane and dived under the still-falling roof-beams. There were three, four, half a dozen men in fleet uniforms, with blasters in their hands. They used the weapons ruthlessly upon a civilian who flung himself at an incongruously brand-new signalling apparatus in a corner of the shattered house. A second man snarled and savagely lunged at his attackers; he was also blasted as he tried to reach the same device.

There was no pause. Over the low ground to the west a flight of bombers appeared, bellowing. In mass formation they rushed out above the sea. Far to the right and high up, a second formation of man-made birds appeared suddenly. It dived steeply from invisibility toward the water. Over the horizon to the left there came V’s of bomber-planes, one after another, by dozens and by hundreds. More planes roared above the shattered shack. They came in columns. They came in masses. From the heavens above and over the ground below and from the horizon that rimmed the world, the planes came. Planes from one direction crossed a certain patch of sea.

They were not wholly clear of it when planes from another part of the horizon swept over the same area, barely wave-tip high. Planes from the west raced over this one delimited space, and planes from the north almost shouldered them aside, and then planes from the east covered that same mile-square patch of sea, and then more planes from the south....

They followed each other in incredible procession, incredibly precise. The water on that mile-square space developed white dots, which always vanished but never ceased. Spume-spoutings leaped up three feet, or ten, or twenty and disappeared, and then there were others which spouted up one yard, or two, or ten. There were innumerable temporary whitecaps. The surface became pale from the constant churning of new foam-patches before the old foam died.

Then, with absolute abruptness, the planes flew away from the one square mile of sea. The late-comers climbed steeply. Abruptly, behind them, there were warning booms. Then monstrous