Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

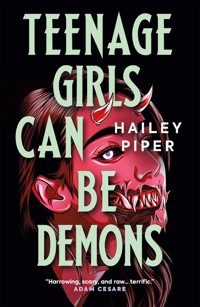

13 terrifying coming-of-rage stories from the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of Queen of Teeth, perfect for fans of Clive Barker, Mariana Enriquez and Eric LaRocca 13 coming-of-rage stories the way only Bram Stoker Award-winning author Hailey Piper can tell them—wildly inventive, brilliantly imaginative, and completely and utterly enthralling. A vicious group of college upperclassmen prey on the freshman girls in "Why We Keep Exploding;" an impossible world of sinister desire opens beneath a family basement in "A Living Piece of Time;" a girl on a night out realizes a bizarre cop is hunting her in "The Long Flesh of the Law;" and in the acclaimed novella "Benny Rose, the Cannibal King," a Halloween prank goes horribly wrong when a murderous ghost steps out of an urban legend and into the real world. These stories take our most difficult years of transformation and twist them into new and terrifying shapes, where the monsters are real and you'll do whatever it takes to get away, or get even.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Leave Us a Review

Copyright Page

Title Page

Why We Keep Exploding

Unkindly Girls

The Long Flesh of the Law

Thagomizer

Without a Face

Last Leaf of an Ursine Tree

Hopscotch for Keeps

Magical Girls Child Crusader Squad

Autotomy

The Turning

We Who Hold the Median

The Many Sins of Clara Greenstone

Benny Rose the Cannibal King

One: Halloween 1986

Two: October 27, 1987

Three: Halloween 1987

Four: And Now, The Weather

Five: Ghost Stories

Six: The Cul-De-Sac

Seven: Lemon Fair River

Eight: Windows

Nine: 6 Glade Street

Ten: The Blackwood Devil

Eleven: The Weak One

Twelve: Silver Bullet

Thirteen: Established 1963

Fourteen: Arthur

Fifteen: Desi’s Girl

Sixteen: The Grave

Seventeen: Day of The Dead

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Teenage Girls Can Be Demons is Hailey Piper at her best. In a publishing world where the novel reigns supreme, here a collection is the only way to really get to know the multiplicity of Piper’s work. Harrowing, scary, and raw, most often all in the same story, with topics that range from the surreal, to the nostalgic, to the all-too-real. Terrific.”

ADAM CESARE, Bram Stoker Award®-winning, USA Today bestselling author of Clown in a Cornfield and Influencer

“Nobody writes grounded cosmic horror like Hailey Piper. That might seem like a contradiction in terms, but read these thirteen wild—and wildly different—tales and get a taste of just how Piper can twist you into otherworldly shapes while still reminding you of your essential, heartbreaking humanity.”

NAT CASSIDY, bestselling author of When the Wolf Comes Home and Mary

“Powerful, wickedly clever, and deeply intimate, Hailey Piper delivers a searing and entertaining anthology that speaks to the female rage of becoming. Delightfully and thoughtfully drawn.”

DAWN KURTAGICH, bestselling author of The Thorns

“Teenage Girls Can Be Demons is sure to be a standout collection in 2025. Check out this fabulous and fearsome book as soon as you can.”

GWENDOLYN KISTE, Three-time Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of The Rust Maidens and The Haunting of Velkwood

“With a delicious focus on rage and transformation, Hailey Piper’s second collection offers up tales that are as bold as they are beautiful. Piper’s ability to dive into the gooey substance that makes humans both fascinating and horrifying is such a marvelous strength. A demonically good time that you don’t want to miss!”

SARA TANTLINGER, Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of The Devil’s Dreamland

Also by Hailey Piperand available from Titan Books

A LIGHT MOST HATEFUL

ALL THE HEARTS YOU EAT

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Teenage Girls Can Be Demons

Print edition ISBN: 9781835411469

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835411476

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Hailey Piper 2025

Hailey Piper asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

TEENAGE GIRLSCAN BE DEMONS

“Maybe I was never a child. Maybe I’m tendons and ligaments wrapped in gauze. Maybe this is all something else and none of this matters?”

—Cynthia Pelayo, Crime Scene

“Everyone expects you to just be happy. Everyone acts like it’s over, but it doesn’t feel that way. Everyone wants to sweep it under the rug as if it never happened. But it’s still happening. I... I’m angry. I’m so very angry.”

—Ally Malinenko, This Appearing House

WHY WE KEEP EXPLODING

Just a joke

The first girl explodes on the final evening of orientation weekend.

Allison Greer, Sutton University freshman, joins us in the dining hall, where all levels of college kids pack the inside, clacking dishes and loud voices bounding off every surface. Beneath that cacophony, no freshman would fear silence.

The boys who join us at our table are upperclassmen. They forego hoodies and torn jeans for stiff button-downs and slacks, like they have job interviews scheduled after dinner. Juniors? I can’t say for sure.

The tallest, a blond boy with razor-straight teeth and a narrow face, sits across from Allison. I can’t make out their conversation through the noise, but he points repeatedly to a cup of yellow liquid, likely beer, and then taps a penny on the tabletop, and I understand this is some kind of challenge.

She tells him she doesn’t like games. When he doesn’t let up, she curses him and throws her glass of fountain soda into his face.

I stare, awestruck, while Tall-Boy sputters. Shaking my head always felt like drawing too much attention, let alone cursing and splashing. I dread the glint in others’ eyes, how I’ll turn from human to thing in the flick of an internal switch the moment they realize I’m different. Vocal training hasn’t come as easily to me as other girls still recovering from early testosterone infection. Some self-teach or find others to teach them. A few like their voices and insist everyone else had better deal with it.

I should be grateful that silence is my friend, that others don’t clock me at a glance and figure out how I’m different from other girls. Lucky little Laurie started estro at fourteen.

Most days, I keep strict posture and bite my tongue. I would never throw soda into anyone’s face. Had Tall-Boy challenged me instead of Allison, I would have agreed to whatever game he wanted. Boys like him twist sorcery on their tongues. They insist you play with them, and I’m easily witched.

Allison is my heroine for a few brief moments. She turns to stride from the table, a victorious warrior abandoning a corpse-choked battlefield. Carbonized droplets skitter down Tall-Boy’s face while his friends laugh at him.

But then he weaves sorcery. “Chill, sweetie,” he says, wiping a paper napkin down his face.

She turns to snap at him, dark hair coiling: “Chill yourself, asshole. Goodbye.”

He leans over the table, and I see the witchcraft swirl in his piercing eyes. “Somebody has an attitude problem,” he says. “It was just a joke.”

Allison’s lip curls back, but she hesitates. Her gaze darts back and forth, uncertain, sizing up witnesses and how they might judge her reaction. Was she the kind of girl who couldn’t take a joke? She had to get her words just right or else see the dining hall condemn her a stuck-up killjoy for all time.

“Try—” she starts, fighting tooth and nail to get the words out. “Try. Being. Funny.”

Tall-Boy turns on his debate me voice. “Humor’s subjective,” he says, smooth and smarmy. “Asking me to adjust for you when we barely know each other, that’s completely irrational.” His eyes stab through her, reading when she’ll try to speak again. He doesn’t let her. “Just a joke,” he repeats, this time coated in slime.

Allison’s lips fight her face to make words. I don’t know what she would say if she could speak. I would like to.

Instead, the silence clamps over Allison’s paling complexion, her dark hair shimmering with milky starlight. She clutches her gut, as if the unspoken words now burn her belly. Her legs stagger back from the table.

Tall-Boy and his friends lean in, like they know what’s about to happen. Sorcerers must have that power.

Allison’s skin ripples. Every muscle twitches. If there’s a sound building toward what’s about to happen, I can’t hear it beneath the dining hall din, Allison rendered silent. I read words in her face, the ones that have done this. Just a joke. Attitude problem. Irrational.

And then she has no face. Her body flashes out, a sudden supernova of white light and viscera. I cover my eyes, but the boys keep looking, their heat oozing over the table, dwarfing Allison’s cold, starlit explosion.

She doesn’t even scream.

When I finally uncover my eyes, there’s nothing left of Allison. The white-light explosion has burned away her every cell. She’s erased, the boys having silenced her forever.

I’m not the only one looking—the place where she stood has the entire dining hall’s attention except for Tall-Boy and his friends. They’re looking around, making sure this explosion has been seen and understood.

They meant to make an example of her, and they have.

They leave us then, point made. We freshman girls sit quietly, out of respect for our deceased hallmate. The moment of silence stretches to dinner’s end. Back in the dorms, someone is sobbing.

Not me. I’ve seen quiet horror. In high school, boys used to silence with fists and boots; here they use words. This is the way of college.

Have my hallmates absorbed the lesson?

Quiet girls don’t get clocked. We aren’t made examples.

Quiet girls don’t explode.

Emotional

I watch the chattier freshman girls when crossing the quad or getting coffee at the open-air campus center—the ones who haven’t learned.

One of Tall-Boy’s friends reminds me that silence is a blessing. He circles the chatty girls, a shark sizing up swimmers, and intrudes with his debate me voice, egging the girls to engage him on human rights or politics or some superhero movie. Given time, one will speak, and then he mocks, and interrupts, and chastises. He puts her in her place. When she’s upset, he calls her “emotional,” and it’s a silencing nail hammered through her tongue. She’s learning terror, one syllable at a time.

Unspoken words can’t escape. I watch her swallow them, and they stew in her guts like trapped gas in a mine. The more she tries to talk, the worse the pressure. It’s slow for some girls, quick for others. Sometimes, when crossing campus, I hear a distant eruption, and I know we’ve lost another.

Survival requires silence. This is the way of college.

When do the boys turn from freshmen to sorcerers?

Who teaches them the silence spell-words?

Why don’t they warn us before it’s too late?

Allison wouldn’t have come here had she known what Tall-Boy’s tongue would do to her. She wasn’t the type to be silent.

Except getting a rise from her was Tall-Boy’s game. She didn’t know better—how could any of us? Freshmen mouths might spit fire, but we know nothing of spell-words.

Our fingers are smarter. On the way out of the dining hall one evening, I steal a knife.

Irrational

Alone in the dormitory shower, I slide the knife down my upper arm and cut a small letter into my skin—A. The shape is ragged; the blade could be sharper. I tell myself that this is how I’ll remember Allison when we took no selfies together; there is no body, no candlelight vigil.

We’re afraid our gathering at campus center will lure the boys. They would hear our sneakers squeaking across cobblestone and be drawn like sharks to blood in the water.

I want the second letter to be L, and then L-I-S-O-N, but I’m no longer certain Allison had two L’s. Instead of overthinking it, I let the blade take over.

Knives have always made sense to me. Hormone therapy has treated my features down to a cellular level, but deeper than that, our flesh holds bad habits holy. I thought I quit cutting myself in middle school, but a smoker smokes when the chips are down, and a cutter cuts. Transition during high school only pressed the pause button.

Still, I haven’t been trapped in that what am I? body for years. Things have changed, even the cutting.

When I glance at the knife’s work, I find the A is not the beginning, but the center. Before it, I’ve carved J-U-S-T. After, I’ve carved a J. I finish what the knife began and carve O-K-E myself.

I carve further spell-words. It’s nothing like my old cutting: every bleeding stroke less about dulling psychological pain, and more about creating protective sigils. Silence spells will find themselves carved in my skin and scurry back to their masters. The boys can’t witch me with words I’ve bled.

That’s the theory, anyway.

Smile

There’s a trick to keeping boys from telling you to smile. Most girls ignore or retort, but “smile” here is another silence spell. No comebacks, only combustion.

The trick is to always smile. The worst these boys can say is “Smile bigger” or “Show some teeth,” but they never do. No matter how rancid I feel inside, my cheeks tug the corners of my lips. The expression is reflex now; no need to think, no effort needed.

I probably smile in my sleep.

Maybe it’s that façade of cheery disposition that draws this boy to me as I cross campus center. He has a wolfish face, jaw hugged by scruffy dark hair, but his eyes look wide and unassuming, almost innocent. Their pretty gaze doesn’t fit his lupine form, two damp orbs stolen from some gentle giant.

His voice is likewise sweet. “This sounds weird, and it’s okay if you don’t want to talk to me, but I just—sorry, I’m not good at this. Hello.”

When I wave at him, he smiles, and my lips tug a little tighter from my teeth.

“You got a name?” he asks.

An invitation to speak, not like Tall-Boy’s prodding. I tell Wolf-Boy my name, keeping my tone neutral, and I never stop smiling no matter the syllables. Keeping my voice tender to temper his. Sweet as he might seem, he’s still a boy at Sutton University. I cannot trust him.

He’s flummoxed though, makes sure to say my name as many times as can fit in his sentences, like it might flit away if he doesn’t catch it. He chats at me until we reach the edge of the dorms, when a growl cuts through my body.

I slide a concerned hand over my middle. Does this count as breaking my silence? Will Wolf-Boy cast a spell?

“That’s adorable.” One arm folds around my elbow, and he leads me from the dorms. “Let’s grab dinner. My stomach’s rumbling too.”

I let him escort me toward the dining hall, my face smiling to mirror his, but I scowl inside. That growl wasn’t my churning stomach.

It felt like my skin.

Calm down

Outside the dining hall entrance, I excuse myself to the ladies’ room. Wolf-Boy doesn’t roll his eyes or chastise. Maybe the bar is too low at Sutton University, in this world, but his lack of impatience feels like hope.

I slip into a stall and pull up my shirt. I’ve carved letters beneath the short side of my ribcage, as if I-R-R-A-T-I-O-N-A-L can pretend that hormone treatment grows the absent strip of bone. Around the letters, skin ripples, a pond disturbed by thrashing fish.

Like Allison’s skin before the end.

Maybe college just does this to girls, tells our skin to run away, fast as it can.

Or has carving the spell-word into my flesh stuck the sorcery inside? The words manifest, but unlike for other girls, my skin’s set to unravel, muscle sloughing from bone. Different girls might self-destruct in different kinds of ways.

Not an explosion, but a meltdown. How long until the sorcery kills me?

If I’m dying, I don’t want to die alone, and since there’s no one else in the ladies’ room, I find Wolf-Boy in the dining hall. I’m not sure if he’s genuinely interested in me or if he’s playing games like Tall-Boy. If I step away, tell Wolf-Boy, Goodbye, in Allison’s fiery tone, will he toss a spell-word or let me go?

Worse, if I like him, will he want me to speak more? Boys can be harsh. Sometimes I envy the girls who like other girls. I used to radiate the sun, but hormones cooled my blood. The only girl I ever dated had hands and feet as cold as mine, lizards attached to our limbs. Boys are furnaces, and I crave the warmth.

Sometimes attraction is that simple.

We eat slowly, and I let him do the talking. Never spell-words, always gentle. He urges a few words from me here and there, but they’re scaffolding through which he builds his side of the conversation.

“Where are you from?” he asks.

“West,” I say, tender yet neutral, still smiling while I chew.

He has no opinions about that, and asks, “What’s your major?”

“English.”

He has opinions there, my answer prompting his every thought on literature classes, majors, and degrees. On the surface, I hear his critique. Deeper, I wonder if an onslaught of opinion is another means to silence me, a complex string of pieces that form a spell. Should I be terrified? My skin growls, but the dining hall din smothers the sound.

Even my body is silenced, but that’s better than exploding.

When will the meltdown take me? Do Wolf-Boy and I have time for kissing and touching first? He’s barely an acquaintance, but if I lead him to my dorm room, he’ll follow. Will a nod be my consent for more? He’ll have to notice the spell-words carved into my skin. I might even drag him into the meltdown. And shouldn’t I mention how I’m different from other girls? My last boyfriend knew before he asked me out. Will Wolf-Boy still see that I’m human, or will I become a thing?

When it comes to girls, sometimes boys see little difference. Even the ones with sweet eyes.

As we leave the dining hall, his arm once again hooked around mine, I realize we’re not going to find out how he sees me. Campus is no place for closeness or honesty. Another freshman girl whose name I’ll never learn cowers at the edge of the dorms, caught in Tall-Boy’s shadow. His friends linger close. Girls keep their distance, weaving around the scene or watching from doorways.

Wolf-Boy strides toward the cluster, a solitary angel who might make a difference in this undergrad hell. A familiar itch crosses my skin, the kind when you want to drag a boy by his jacket into your bedroom and then tear away that jacket and everything else.

The nameless freshman girl turns to speak to him, probably to plead. Her face is scrunched, desperate.

Wolf-Boy holds up an open palm. “Calm down,” he says. “What’s the trouble?”

Desire’s itch washes off my skin, and the growling ripple returns. Tall-Boy and his friends lean in, expectant, but Wolf-Boy stares oblivious. My sweet wolf has no idea he’s spoken another silencing spell.

I can’t watch. Without waiting for him, I skirt around the crowd and run for my dorm’s front doors. He doesn’t mean to cast spells, but he can’t help it. They are the words he knows. How long until he slings them my way? I catch the girl out of the corner of my eye, wrapping her arms around her torso as if trying to hold herself together. She’s already reached her limit from Tall-Boy. Wolf-Boy’s pressure is too much. She’s done.

As I rush inside my dorm hall, I hear her explode.

Neurotic

My skin twitches harder each day. Wolf-Boy watched me run, and now he haunts my dorm hall. “Laurie, you there?” he calls, but I never answer. He might tell me to calm down, and I won’t risk it.

No one guides him to my door. We girls are frightened, and the boys down the hall don’t know my name. Those immune won’t answer him—the musician who speaks more Mandarin than English, the history major with hearing aids, the non-binary students scattered between binary hall designations. They can’t share their safety.

Not that I blame them; I can’t share my knife.

And I can’t quit cutting. My skin growls non-stop, every pore a mouth caught mid-snarl. Beneath the shower’s spattering rain, I try to relieve word-driven pressure, but whispers aren’t enough. Something inside me wants to roar.

Only carving settles my skin. I imagine spell-words Wolf-Boy might lace on to his opinions were we to peel each other’s clothes off and bare my cutting. R-I-D-I-C-U-L-O-U-S. N-E-U-R-O-T-I-C. T-O-O and then M-U-C-H. I empathize with tattoo lovers—I’m running out of spare skin.

Still, no meat sloughs off. If I’ve averted the meltdown, will I still explode? Too many theories swirl inside—maybe I’m too different from the other girls. Maybe surviving attempted self-destruction years ago has helped me build antibodies. Maybe the carvings do their job so that Tall-Boy and friends can’t destroy me. Maybe I haven’t given them a reason.

And Wolf-Boy? In a darkened room, he might not notice my carvings. He might not care how I’m different. If my fingertips coax him to growl like a wolf, he might not hear my skin do the same.

But Wolf-Boy, Tall-Boy—they’re of one nature. The boys pronounce themselves individuals for conflicting views on ethics, culture, and history, but they’re each sharks in the same ocean. Tall-Boy the Cruel, but he’s just joking. Wolf-Boy the Cruel, but calm down because he doesn’t mean it. Surely the others have spiced up their cruelty to help live with themselves.

Excuses, excuses.

Our upperclassmen know when to be silent and when to speak—when spoken to. Those of us who survive our freshman year will grow into sophomores if we learn the same, a mandatory class we obliviously enrolled in upon orientation. Sutton University’s spell-word crucible will destroy the rest.

In the end, we girls will likewise be of one nature. I won’t be a different kind of girl anymore. Isn’t that the dream?

As my skin ripples, filled with wolves and leopards and every growling angry beast that’s ever walked this world, I wonder—if that’s the dream, then what’s the nightmare?

And the boys? What’s their nightmare?

Attitude problem

Weeks have passed since Allison’s death, but I finally muster a candlelight vigil for her. For all the girls who’ve exploded. I pass notes through the freshman dorm, meant for the girls, but others will find them, too. They’ll spread the word.

The lure.

We gather after sunset at campus center to raise candles. This moment of silence might have stretched until midnight, but I hear Tall-Boy’s snide voice at the crowd’s edge. He’s playing the shark, testing us for weaknesses. Sizing up who to bite.

I don’t understand why he does it. Probing the freshman population for what he considers girlfriend material? A lackluster comedian hunting an audience for when he’s just joking? Does he like to watch us brim with starlight and suffer explosions?

Or does he do it because he can?

I muscle through the vigil’s crowd and find he’s not alone. His cluster of friends traipse behind him in matching button-downs, eyes on their leader. I storm between him and the other girls, my candlestick spattering on cobblestone. Skin and mouth growl together as I hurl insults, telling him exactly what I think of Tall-Boy’s unjust jokes, creepy grin, and shark-like face.

He smirks at first, but his confident mask crumbles when his friends snicker. Spell-words spit off his lips, sprinkle my face.

I shout an onslaught of opinions to rival Wolf-Boy’s. Every word’s emotional, my voice clumsy, my skin snarling, and I’m not sorry for it, and I can’t stop. I won’t stop. That’s why Tall-Boy, tongue flustered, finally storms forward and shoves my shoulders.

I crash onto the cobblestones. My skin quits growling, the pain welcome, and I can’t help the cracking shout that shoots up my throat. It is an old voice I keep meaning to leave behind.

The glint shifts in Tall-Boy’s eyes. “Oh,” he says, piercing gaze at last seeing me. Clocking me. His barracuda smile returns.

The moment stretches in pregnant silence. I’ve turned from human to thing in his eyes, but I don’t mind because that’s how he sees every girl here. It’s validating in a terrible way. He wants to sling spell-words fashioned solely for me, the kinds of slurs you’ll find for a dime a dozen on any street.

But I don’t let him finish. I barely let him start.

“That’s why it doesn’t work,” he says. “Because you’re not really a—”

I stand quick and thrust my face into his. “I’m not done,” I snap.

His tongue limpens, and his jaw goes slack. No slurs, no spells. No jokes. The words slide down his esophagus and into his stomach, where they froth and rumble.

He tries again. “You—”

I lean closer. “Don’t interrupt me.”

Again, he swallows his words. His friends aren’t snickering now; they realize in fits and starts what’s happening to their tall leader. Behind me, the girls cluster. They’re still silent, but they’re watching.

Someone who isn’t silent appears from the gloom beyond the crowd—Wolf-Boy. His scruffy face doesn’t smile now. He scowls at Tall-Boy, who’s gripping his guts, and then at me. Wolf-Boy thinks he understands, but he’s thought that before and been wrong.

Still, he tries. “No need to fight, right?” he asks.

Each word rings earnest. I know he only means the best, can’t see the damage he does, how he props up boys like Tall-Boy and shatters girls like the nameless freshman he told to calm down. It would be easy to fall into his oblivious arms and let his furnace warm me.

But I can’t.

His mouth opens again to ask, “Why don’t we just calm—”

“No,” I snap.

Like a scolded dog, he bows his head, and I imagine his ears drooping. I won’t let him tell me to calm, or settle, or chill. Not anyone else, either. Good intentions don’t matter; a spell-word is a spell-word. Wolf-Boy has his innocent mistakes, Tall-Boy has his humor and viciousness.

And we girls have our vengeance.

I sling spell-words at Tall-Boy. Ones he knows, like irrational and attitude problem. Ones he doesn’t, like no. I speak ones specially for him, like sad and worthless and empty. The harder he tries to smirk through it, the deeper my tongue carves them into his body.

Other freshman girls chime in. They only speak the words I use, but an echo is better than silence. We know what this will do to him now, and we mean it. We aren’t joking. We are far from calm.

Because girls can be cruel, too.

And I make sure everyone sees. Tall-Boy will turn example at the center of campus. This is the way of college. Sutton University might trigger spell-words to explosions, but we’ve all been silenced before. Tall-Boy hasn’t. He’s never been put in his place, has no tolerance to the pressure. It builds quickly inside him.

I strip off my jacket, roll up my sleeves and leggings, expose my midriff and ribs and every spell-word etched into my skin. A new carving tattoos my sternum, and I speak it now. It echoes the first exploding girl. One last spell-word to bring white light bursting from the first exploding boy.

Silently, I thank Allison for teaching it to me.

Goodbye

UNKINDLY GIRLS

On the third morning at Cherry Point, Morgan met the unkindly girls. Dawn had hardly touched the beach, giving the sand a grayish tone. Red rocks dotted the stone path from their small white beach house down to the water. Up the shore, a fishing boat cast off.

Morgan wore the ugliest swimsuit. Dad’s decision—a one-piece, dull maroon abomination with sleeves and shorts. She’d never been allowed to wear a bikini, but in the past her swimsuits had looked presentable. The designer must’ve thought the faintest hint of shoulders and butt would draw too many wandering eyes.

Dad probably agreed. “You’re still my baby girl,” he’d said when Morgan complained. Six years old versus sixteen made little difference to him. He would scoff when he saw women and girls wear more revealing swimsuits. He’d call them unkindly—one of his favorite words, as if to look appealing meant flipping him off.

But Morgan had spent her life at his side and had seen him lick those chastising lips. She was not to become an unkindly girl. Never.

“You wouldn’t do that to dear old Dad, Morgie,” he’d say.

She’d come out early to dip into the water, but with so few people wandering the beach, she had her pick of seashells. The more colorful, the better. Hunting for them used to be a treat. Dad would only let her keep three per trip. He said to take too many would damage the ecosystem or something, but the hunt was the fun part.

Now, every shell that sparkled on the beach turned dull in her hands. She let them tumble back to the sand, one by one. A lot had changed at home since last summer. Try as she might to leave it behind, the change had followed her to Cherry Point.

“That is the ugliest thing I’ve ever seen.”

Morgan dropped her last lackluster seashell and looked down the beach, where two girls her age walked the damp sand. One’s face was all angles and wreathed in dark hair. The other flashed a soft smile; white stripes patterned her red hair where she’d bleached it. They wore dark, baggy pants and loose-fitting blouses that bared their chests.

Unkindly. The word popped unwanted into Morgan’s head. She’d never glanced at other girls’ chests the previous summers, but now Dad’s eyes dominated hers.

“Like wearing blood,” said the pointy-faced girl, still fixated on the swimsuit. “Sickening.”

“Isn’t it?” Morgan asked, tugging one stunted sleeve. “That’s what the tag says. Ugliest Swimsuit, one size fits none.”

The two girls giggled, and then the pointy-faced one beckoned Morgan. “I’m Blue, and the redhead’s Clown. Follow us. We’ll fix you up.”

Morgan smiled to herself and obeyed. This wasn’t unusual for summer vacation. Somehow, she always made at least one friend.

Neighbor houses squatted a couple hundred feet from each other, but closer to the wet sand stood a dull wooden shop. Water damage darkened its lower walls, and the discoloration gave the shop a sea-worn feel.

Blue and Clown led Morgan inside. Plastic shovels and pails dangled from nails, snorkels lined a metal tray, and bathing suits hung on a circular clothing rack. Plus, there were shelves of the usual gift shop garbage. A tacky ceramic crab clutching a flag in its claw read, “Ain’t Life a Beach?”

The shopkeeper, a balding man with a scraggly goatee, let his eyes wander up and down the other girls’ bodies. Morgan thought of Dad and how he’d never be so obvious. His shame always forced him to avert his gaze.

Fabric swatted her arm, tearing her gaze from the shopkeeper. Clown shook a plastic hanger, dangling an aquamarine two-piece swimsuit with navy-blue striping. Shiny sequins lay trapped between layers in the trim. They looked almost like scales and made Morgan think of mermaids.

“Lovely, yes?” Blue asked. Her smile was all teeth.

Morgan shrugged, but Blue was right. It was gorgeous.

Blue guided the bikini to Morgan’s front. “On you. To die for, yes?”

Exactly Morgan’s thinking. Dad would kill her.

Morgan stepped back, letting the two-piece dangle again. “It’s pretty, but I don’t have money.”

“We’ll spot you,” Blue said, taking the hanger from Clown. “In return, you hang with us tonight on the beach. Agreed?”

Morgan shrank inside. If only it weren’t so easy to make friends, Dad would have no one to chastise, and these would be peaceful vacations, nothing more.

Blue laid the swimsuit on the counter. The shopkeeper didn’t look at her now, his eyes sharply focused on the cash register. Clown reached inside her blouse and pulled out a black purse. Dollar coins thudded on the checkout counter. Morgan couldn’t see their faces, but they made her think of pirate doubloons.

Blue pressed the swimsuit into Morgan’s arms. “At the beach, just before sunset.” She marched past, and Clown trailed her.

Morgan began to follow them out.

The shopkeeper cleared his throat. “Watch out for them two.”

Morgan turned to him. “What?”

He ran his fingernails from temple to goatee, scratching an itch he couldn’t catch. “Every summer, they come to Cherry Point and sell dope up and down the beach. Don’t get caught in their mess.” He began to fiddle with a coin, but his eyes focused on Blue and Clown as they sauntered out the door.

Vacationers, not locals.

They were just the kind of girls who’d make Dad avert his eyes.

* * *

If they would stop going to the beach each summer, maybe he wouldn’t have to see any unkindly girls. Sometimes he saw them at the pool in Syracuse, but nothing would come of that. Too close to home.

When Morgan was little, she’d thought their beach trips were a fun way to spend each summer together after Mom died. Cape Cod, Miami Beach, La Jolla. Different coasts, different kinds of beaches, but always full of sand castles, ice cream, and splashing in the shallows, though never past the sea shelf where the undertow might suck her into the deep. Safety first was one of Dad’s rules.

At each beach, Morgan made a friend. She never meant to. They would stumble into each other, or Morgan would see the other girl wearing something pretty. A day would pass, Dad would disappear for a night, and then they would head home.

Morgan tiptoed through the beach house and into her room, where she stashed the aquamarine bikini beneath her sagging mattress. Cool salty air swept through an open window and across her arms. She stripped out of her maroon one-piece and dressed in a tank and shorts. She’d meant to swim, but now a grimmer outlook haunted her thoughts.

She would have to tell Dad about the girls. Since Mom was gone, she’d told him everything, even after she realized he hadn’t been telling her everything in return.

Utensils clinked in the kitchen. He was awake.

She stared at her window, thinking about sneaking out, but Cherry Point lay hundreds of miles from Syracuse. If she ran away, she’d just have to come back. He would think her unkindly for worrying him, and he might then worry that she knew his secret.

She traipsed into the kitchen. Dad loomed over the stovetop, his thick yet dexterous fingers sliding an egg from bowl to rim to pan. He wore a blue and white Hawaiian shirt, khaki shorts, and white sandals. Harmless middle-class vacation father—his best costume.

“Morning, Morgie,” he said. “Out early?”

“I wanted to swim while it was cool,” she said, plopping down on a stool by the kitchen island. The pedestal creaked around a loose screw.

“Your hair’s dry.” Dad didn’t look at her. Somehow he just knew these things. Another egg cracked and sizzled.

“I didn’t get a chance. I made a friend.”

Dad focused hard on his hands as he slid his graceful spatula beneath the omelet. It flipped and hissed against the pan. “That’s nice.”

“A couple friends, actually.” The cold marble countertop felt soothing under Morgan’s palms. If she kept them there, could she keep from getting blood on her hands?

Dad picked up a knife. Its blade slid around the omelet, sawing off brown arms of crust. “Staying safe, right?” he asked, working magic with pepper and cheese. “Staying kindly?”

Dad laid a plate on the countertop. The omelet was perfect, Dad having cut off all signs of burning and crust without losing any of the cheesy yellow center.

Morgan swallowed before biting. “Yes, Daddy. Always.”

He would watch her leave tonight. He would see Blue and Clown, and then lick his chastising lips.

* * *

Morgan didn’t say goodbye in the evening. They wouldn’t really be apart, after all, though only she would approach the beach, where the unkindly girls sat around a small fire just outside the tide’s reach. Coastal winds batted at the flames. A storm was coming.

“Now what are you wearing?” Blue asked. She and Clown had not changed out of loose-fitting blouses.

Morgan wore baggy jeans and a hoodie. She’d told Dad that it was going to be chilly this close to the water tonight.

“Where’s your swimsuit?”

“Under my clothes, same as yours,” Morgan said. The girls tittered, and she realized their cleavage was still on display, no hint of bikini tops underneath.

Clown tugged a large brown bottle from the sand beside her feet, took a swig, and passed it around the fire, first to Blue and then to Morgan. There was no label. Brine clung to the bottom, as if the glass had been trapped in a shipwreck for a hundred years.

She thought of Dad and passed the bottle back to Clown. “Anything fresher?”

“We’ll have something fresher after sunset,” Blue said. She and Clown tittered again, the only sound Clown seemed to make. Her hair caught the firelight; its shadows twitched this way and that, as if alive.

As red and purple dusk gave way to black, cloud-covered night, the small fire became an island of light on the beach. Windows glowed down the beach, except at Morgan’s house, but the rest of the world was dark. She wondered exactly where Dad was holed up. He could be anywhere the light didn’t touch while the campfire illuminated the girls for him.

She’d figured things out after last summer. It wasn’t like in the movies where he might’ve accidentally left out some crucial clue that grabbed her attention or a serendipitous news article happened to link their past vacation locales. She was older now and getting attention from boys at school. The way they looked at her wasn’t so different from her father. They were just too juvenile to feel shame. Then there were his comments, his averted eyes, and the nights he’d go out before they left their vacation spots for home. Her brain had linked the chains.

Now she wrapped those chains around her legs. She wondered what heavy thing she’d tether them to and throw into the ocean to drag her down.

“The night’s ready, girls,” Blue said, standing up and turning to Morgan. “Fancy a swim?” She didn’t wait for an answer, just tromped toward the water and expected the others to follow.

They did. Where the tide lapped at their feet, Clown spun around and held out a fist to Morgan. She took the offering, a coarse square that reminded her of dehydrated fruit.

“Ever been swimming high?” Blue asked. “Unforgettable.”

And unkindly. Morgan made to pass the square back, but Clown was already running into the tide.

The light was gone. Dad would never know, same as he’d never know about the sequined bikini. Morgan lifted her palm to her mouth, and her lips closed around the square.

“Melts on your tongue,” Blue said. She was already knee-deep, the tide drenching her clothes.

Morgan stripped and followed. Salt spray stung her nose. Her mouth filled with the static that blew from Dad’s radio when he let her switch between stations. The other girls bobbed, dark driftwood on black waves.

Vague warnings slid beneath Morgan’s thoughts. “The shelf. The undertow.”

Thunder and waves drowned her out. The girls drifted farther. Morgan meant to follow. Only the thought of Dad anchored her to land. She wasn’t an unkindly girl. Never.

Waves rolled toward her. She took a deep breath, stinking of seawater, and plunged beneath the surface. She couldn’t see underneath, but somehow she knew that Blue and Clown were diving, too. The ocean became less an undulating wave, more a hand that grabbed Morgan and yanked her deep.

She floated beneath the creaking hull of an aging ship, its underside as glassy and coated in barnacles as the bottle passed between Blue and Clown. Inside, pirates dragged helpless hook hands against smooth walls. Their glass prison was filled with seawater and beer, and their pockets were so loaded with doubloons that they couldn’t swim away.

Blue and Clown beckoned Morgan to the surface, their scaly turquoise and orange tails flapping. Neither mermaid seemed unkindly. They just wanted to see selfish men die.

An enormous golden tail rocked the drowning ship. The black sky flickered alive with lightning, painting the silhouette of an enormous woman against the clouds. If Blue and Clown were guppies, she was a shark. Plains of kelp matted her scaly head, and coral coated her arms. One gargantuan hand grabbed the bottle by the neck and slung it at the sky. It shattered in thunder, and its shards sliced every pirate to pieces. Their lungs flopped atop the water’s surface, helpless as fish on land.

“Unforgettable,” Blue said.

Morgan dug her hands into wet sand and hauled herself onto the beach. The tide splashed across her back, spraying saltwater into her mouth, but her muscles felt too worn to move another inch. Rain pattered the sand. The storm that swirled out on the water had almost reached Cherry Point. Whatever drug Clown had given to Morgan, it seemed to be losing its effect.

Lightning forked overhead, illuminating a smoking mound where the campfire once burned. Morgan thought she saw other shapes closer to the water. She stared hard at black-on-black outlines until the sky lit in another blue flicker.

Two naked bodies lay in the surf, red and white hair swirled around one’s head. A bulky figure kneeled beside them. The flicker faded as he turned to Morgan, and he stared until lightning again tore across the sky. Its flash lit his familiar eyes and made his chastising lips glisten.

“I’m sorry, Morgie, but they were unkindly,” Dad said. Thunder rumbled, and he paused for it to pass. “You know, don’t you? I thought you knew when you told me about them.” He started toward her.

Morgan’s chest ached against the sand. She wanted to slither back into the water. She felt the lightning coming, the sky’s tattling forked tongue, and the beach glowed as blue as her swimsuit. He could see her clear as day.

She lifted her head. “Dad—”

“What are you wearing, Morgie?” he asked, but he didn’t say it like a question. He sounded the same as when she was six, the day he told her Mom wasn’t coming home. Thoughts of him had shriveled out on the water, but now he was here and real, and he dwarfed every fantastical ocean.

“I—I—I—” Morgan tried to stand, but her legs felt waterlogged. She wondered if that was the drug’s doing. She managed to sit up and wrap her gooseflesh-covered arms around her chest.

“It was only a matter of time, wasn’t it?” He sounded calm, almost peaceful. He squatted down, drew her into his firm arms, and scooped her up against his chest. Fire beat inside in time to the spitting rain. “You had to grow up someday.”

Morgan closed her eyes and tried to forget everything she’d realized since last summer. Dad used to be a good man, or at least that’s what she’d believed. She could believe it again, couldn’t she? If he just held her like this and warmed her bones against every chilly seaborne wind, she would believe anything he wanted.

“Daddy, carry me home,” she said. Lightning flickered past her eyelids. “It can be like it was.” She felt him walking, but he hadn’t turned around.

“It can’t,” he said.

Water slopped at her dangling feet. She opened her eyes. The world lay dark between lightning flickers, but she made out frothing waves that encircled them, churned ugly by harsh wind. Dad was walking into the sea.

“Why?” she asked.

“Because I can’t feel the way I feel about unkindly girls for you!” he shouted, loud as thunder. “Not my baby girl. Never.”

She squirmed, but she’d exhausted herself, and he held her tight. Rain and sea crashed across her, plastering her swimsuit against her skin. He didn’t look at her, averting his eyes for when lightning next lit the coast.

He didn’t have to avert them for long. Chest-deep in the water, he plunged her under. One hand grasped her shoulder; the other shoved hard against her head. She clawed at his unyielding wrists and kicked at his legs and groin, but her feet were heavy, the water weighing them down. Lightning reflected in Dad’s eyes. The storm would watch her die.

Was this how he’d killed the other girls, every summer vacation past? Had he held them first so that they might know a loving embrace before drowning them? Always far from home, those unkindly girls. They were vacationers who might’ve met anyone on the beach, but instead they’d met Morgan and her father. Dead summer friends were coming to collect. She had been his accomplice, knowing or not, and she would join them beneath the sea. He hadn’t been caught for murdering them; would someone wonder why he returned to Syracuse alone this time? Would neighbors ask if Morgan died kindly?

He would tell them so. Someone would come to collect him, and he’d say his daughter died still his baby girl. Always.

Morgan stopped fighting. Her lungs screamed to keep thrashing, but she had to catch his gaze. She stared up at him, bubbles slipping from her lips. The sea calmed for a moment, as if anticipating a mighty wave. Dad glanced down at her.

Lightning flashed. She slipped her fingers beneath the lower rim of her bikini top and yanked it up.

Had he waited, the lightning would have faded and he wouldn’t have seen, but even a glimpse seemed too much. His body shuddered backward. He turned his head, eyelids squeezed shut, the sight threatening to drive nails through his eyeballs.

The tide crashed across them, shoving him back and taking her under. It bought her time to break from the shallows. She dove under the next wave. Thunder crashed, but it came warped and uncertain underwater. She thought she might be swimming over the sea shelf by now. Her skin stung with cold as she surfaced.

“Morgie!”

Dad swam against the waves. His drenched clothing tugged at him, but she’d been fighting the ocean for an unknown time, whereas he had a fresh start. He could manage. His fingers snatched her ankle.

If he tried to drown her this far from shore, he’d probably kill them both. Would keeping her kindly be worth the sacrifice?

She looked out to sea for the miracle she’d seen earlier, but there was no static in her mouth, only her tongue. The drug had worn off. No mermaid was coming to save her, same as no one had saved her summer friends in every year past.

She let Dad draw her close and wrapped both arms around his trunk. He embraced her, too. He might’ve thought she was trying to hug him, one last desperate grasp for sympathy.

She sucked in a deep breath and thrust downward hard as she could. Flexing her legs, she kicked herself and Dad into the next wave, where the undertow pulled them under. He was stronger and larger, but freed of land, she could move him.

He shoved at her face. Lightning revealed his flailing limbs—he must’ve missed the chance to take a breath before submerging.

She didn’t let go. Her lungs burned again, still faint from the first attempted drowning. She promised them this would be the last. Fighting him wasn’t just about Blue and Clown. It was about all the unkindly girls he had already killed and all the ones who might die yet. No more.

Burning faded from her chest, her lungs at last giving out. The surface seemed far away, and she was tired. Ghostly cold ate through her muscles. One more unkindly girl drowned in the deep.

Lightning burned in ferocious flashes, the sky playing catch between two clouds, and the world flickered black and blue. An ocean of fish and seaweed appeared. Vanished. Returned full of faces. Morgan might’ve believed they belonged to mermaids or dead pirates, but when the next lightning flash brought them closer, she recognized them.

They were easy to remember; none had aged since she’d last seen them. Little girls, adolescents, teens, Blue and Clown among them. All her summer friends.

And there were strangers who crowded beyond, more than Dad should’ve murdered in the ten years he’d been taking Morgan on summer vacation, more unkindly girls than years in her life. Some were women who might’ve been Mom’s age. Others he must’ve met when he was younger.

He had been finding unkindly girls for a long time. Noticing them and averting his gaze, he poured his strength into unlatching Morgan’s legs. He didn’t seem to realize she was good as dead.

The ocean formed hands in the uncertain darkness between lightning flashes. They hugged him, hugged her. The undertow, the dead—she couldn’t tell what helped her hold him anymore. The difference mattered little to an almost-ghost. No more breathing, eating, or sleeping. No more distracting life functions. She could focus now, all secrets bare, and bend her will and body to one last purpose.

The dead wanted him, and she would not let go.

THE LONG FLESH OF THE LAW

The siren’s cry came distant and warped, a baying wolf across the lit cityscape. Miracle Robinson would’ve ignored it, one more howling among nocturnal hunters, if not for the answering chirp close by, drawing her gaze to the curb at her left.

Sandwiched between an SUV and a small sedan, a city cop cruiser parked streetside at a crooked angle. Rainy residue from an earlier storm twinkled over the other vehicles, but on the cruiser it more resembled a sweaty sheen coating naked flesh, the car having foregone any steel frame to instead become a blue-and-white-skinned beast.

Mira swerved right at the next sidewalk corner, dipping under a pink neon sign. She didn’t want to see the cruiser and couldn’t let whoever drove it see her in return.

Her smartphone’s GPS flickered and recalculated her route. She rarely used it, but the city seemed strange tonight. The streetlights cast an odd shine, yellower than usual. Every silent passerby dragged a long shadow, and the street’s regular cacophony sounded as strained as a creaky old crate stuffed to bursting.

Another siren cried from far away. There were hunters tonight, yes, but they couldn’t be hunting Mira. She’d carefully chosen a dark vest, long-sleeved sweater, and jeans tucked into bland brown boots, the borrowed ensemble screaming college student. Above her round cheeks, flushed with the chill, sat a thick pair of old prescription glasses, giving her the look of a wizened librarian beneath her curly red hair. No one would suspect she was only fifteen.

The deception would be crucial when she met up with the others. Petra had heard of a club called Three of Diamonds that didn’t check IDs, and they were all set to gather there, unbeknownst to parents. Dad was pulling a late night at the firm. He would come home at three in the morning, eyes red, tie loose, arms loaded with paperwork, too exhausted to guess his daughter had returned only shortly before him.

Mira didn’t expect to find a club at the night’s end. Three of Diamonds was likely some below-street gimmick restaurant five teenagers couldn’t afford. They would order water and cheap food, and they’d cackle over gossip and decide they weren’t losers. Mira could be a not-loser with them.

Supposing she ever found the place. The GPS’s recalculation had steered her into a dead-end alley, and now it was recalculating again, aiming her southwest. And now again, aiming east.

Her fingers tensed around her phone. She hated doubling back; it was a good way for someone to catch wind that you were lost.

Like that odd cruiser.

She shouldn’t have been able to see it after turning the last corner, but there it sat at the curb down the street, looking somehow counterfeit, like a clumsy drawing scribbled against the curb. Had it followed her? Or did every cruiser tonight look warped and strange?

Best to pretend she wasn’t alone, wasn’t lost. She angled her phone past her chin and muttered to it in a pretend phone call, as if the shitshow GPS were her friend.

So far, it had offered about as much help as her actual friends. She’d messaged the group chat before tonight’s sirens began, first to re-ask the club’s name, then for directions. Each time, she’d met laughing faces and notes of Hmm, can’t you find it? and It’s so easy, and Yeah, bitch, hurry up.

That last one had turned into much-needed advice. Mira hurried around another corner and down the sidewalk, escaping the cruiser’s sight again. Hopefully for good this time.

At the next corner, she lowered her phone and reviewed its map. Text and icons had morphed into unfamiliar symbols, and the lines and shapes had ceased to make sense. Buildings transformed into bridges; streets became subways. The map kept spinning, changing which direction led to the waterfront, as if the city were spiraling into the sea.

She glanced ahead, doubtful there was a subway station entrance nearby, and spotted a mouth opening downward, braced by grimy railings. Two cops in blue uniforms leaned against its outer wall, eyes on their phones, their service caps obscuring the subway route.