7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

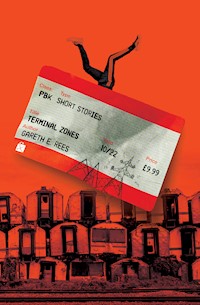

'Fresh and disturbing stories mapping out the pressure points in the psychedelic everyday - Rees consistently reaches the places others do not.' – Will Wiles, author of Plume 'Gareth E Rees propels us into a vast and uncanny future; showing us brief snatches of a world to come. A poignant message delivered with guile, wit and beauty.' – Matt Wesolowski, author of Demon 'Strange, compelling and brilliantly funny.' – Matt Wesolowski, author of Demon Ten tragicomic tales of environmental and personal disaster from the margins of town and country. A troubled hipster is seduced by an electricity pylon. Sinister omens manifest in a supermarket car park. A motorway bridge becomes a father. Malevolent bacteria plague a polar icebreaker. A bioengineered abomination lurks in a Gloucestershire railway terminus. The weekly bin collection pushes a man over the edge. A former squatter clings to her home on a crumbling cliff. Joyriders are foiled by Anglo Saxon floodwaters. Vampiric entities stalk B&Q. And fiery catastrophe comes to the zoo. Gareth E. Rees's first collection of short fiction explores lives on the verge of breakdown, where ordinary people are driven to extremes by the effects of late capitalism and ecological collapse.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

3

TERMINAL ZONES

GARETH E. REES

Influx Press

London

5In memory of Hendrix (2008-2022)

My companion on many walks through marshlands, coastlands, car parks and industrial estates. Without him, these stories would not have come into being.

6

7

Contents

We Are the Disease

On a grey day, we set sail from Murmansk on the International Research Vessel Salvo, passing rows of container cranes and the hulks of decommissioned icebreakers, our worn-out predecessors, doomed to rust. We numbered seventy-five coastguard crew and forty-three scientists. For most on board, it was just another job, and we entered the Barents Sea on course for the Arctic Ocean with no great trepidation about what lay ahead. No sense of approaching disaster. Not of the unexpected kind, anyway. For we lived daily inside the slow catastrophe of the Great Warming. Dead reefs, mass extinctions and rising seas. Flooded cities. Wars over resources. You couldn’t escape it. Every minor act – from switching on a light to flushing a toilet or munching on 10a loaf of bread – contributed to the crisis. Our very existence spelled the end of ourselves, so the notion that something might lie ahead on this voyage which was worse, and more terrifying, did not enter my mind, even though my role on the ship was to look out for imminent dangers.

I led a team which carried out inspections of the Salvo, checking for signs of fire or flood, so that the scientists had peace of mind to carry out their studies, which were of immense importance to the future of humankind. The ice caps were shrinking. Thinning sheets, like magnifying glasses, channelled the sun’s rays into parts of the polar ocean that had been in lifeless darkness beneath thick ice for millions of years, before the rise and fall of civilisations. Light had woken the deep, microbial past. Vast blooms of algae flourished beneath the ice in creeping carpets of green and red. Scientists now believed that the levels of photosynthesis in the Arctic Ocean were ten times higher than previously thought. There was a glimmer of hope that this burgeoning bacterial life could help trap carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and slow the process of global warming. But there was also a larger fear that something novel was emerging which could further endanger human life, like those viral escapees from felled rainforests which had unleashed such devasting pandemics over the past decade. But we needed more data. So this was our purpose: to observe the largest possible extent of the bloom, at the tail end of the summer, before the sunlight vanished.

As with any voyage, we braced for violent, unpredictable weather. Savage storms. Freak waves. Big freezes could grip the pole at any time. Despite its thinning, the ice was not to be underestimated. Rather, instability 11made it more dangerous. It could close in fast. Entomb ships on gargantuan floes, powerless, like wildebeest in a tar pit. Many sailors became spooked. We’d heard recent reports from freighter ships of disturbances beneath the aurora borealis, geysers of light bursting from the ice, screams in the ether, incomprehensible voices, and impossible creatures glimpsed momentarily through blizzards, larger than the extinct polar bear. Of course, we were a scientific mission and didn’t believe this literally. But we were well travelled on this ocean and understood their hysteria. The planet was in awful transformation. Its northern ice cap an expression of its death frenzy, flinging out wild magnetic tentacles as it dissolved into water. This was why we were heading there on the Salvo. To find out what was really going on.

In early August, we manoeuvred between sculpted icebergs of brilliant blue until we reached the pack ice, where the Salvo forced its way through narrow channels between jagged white plains, dotted with emerald pools. There was a dirty, grubby greenness to the outer rims of the ice where it met the water, as if it was rotting from beneath. We moored for a week at a time, while a team led by Chung and Pokrovsky took samples and brought them onto the ship for the biologists to work on. At mealtime presentations, they shared their findings. The bloom was spreading towards the pole, further north than ever recorded, a hundred and fifty miles of the stuff. The sixth mass global extinction counterbalanced by this subaquatic arctic rebirthing.

‘Far more production is happening under the ice than we realised,’ Chung announced one day in the canteen, ‘and the algae is not behaving in the way we expected. It has evolved 12weird genetic mutations that make it… hard to classify… it will take time for us to make sense of it.’

On afternoons off, crew members played football in arctic gear on snow-dusted ice and returned with white eyebrows. My cabinmate, Svenson, was always urging me to play, but I preferred to take in views of the constantly mutating icescape, draw sketches in my notebook and idle with my daydreams. This was why I’d taken on this job, to leave the city and experience the world, to have space to think and breathe. I was in thrall to the possibilities of the moment, the beauty of the now. Gazing at the crystal vista beneath the endless sky, I could forget about droughts and forest fires, riots and famines, nuclear bomb tests and the epidemic of super-immune bacteria that had killed my parents, encouraging my attempt to escape from it all through a job on a research vessel. Missions like ours and those in the depths of the Marianas Trench were, in part, an attempt to find new antibiotics and genetic solutions in the bodies of undiscovered oceanic life forms. Science was a desperate affair these days. I felt sorry for the experts on board, clutching at straws, but this was paid work and it was good to be out in Earth’s last clean air.

In late September, we cut deeper north, crunching through white slabs, meringue pieces crushed by the knife of the Salvo’s bow. Freezing winds made external work painful as the sun dropped ever lower and daytime became a persistent twilight. Days before we were due to turn back for port, we received a distress signal from the American container ship Witness, which had become trapped in pack ice. We were the only icebreaker with any chance of reaching it. The trip took four days through 13insane weather. A storm blackened the stars and trembled the masts. Strange phosphorescent green light shimmered around the hull of the Salvo as it bucked and heaved. A problem with the satellite communication forced us to broadcast on crackly old radio frequencies. Messages from the Witness grew garbled, fuzzy, then died out completely. Eventually, thick blizzard revealed an enormous dark shape like a tilted tower block. It was the Witness. We pushed through to get as close as we could. There were no lights. No sign of life. For all it appeared, the ship was abandoned decades ago.

A brief lull in the storm the following morning allowed Davydkin to take a rescue team across the ice, bowed into the wind, calling urgently through a loudhailer. Hours later, they returned, pale and shaken. The container ship was deserted, its floors coated in slippery algae and fungal growth on the walls. Much of the furniture was littered with tiny white flakes and gossamer-thin sheets of unidentified matter. They brought samples for Chung and Pokrovsky’s team to analyse. We were all unnerved but Svensen and I dutifully continued our rounds of inspection, along with Wilkinson, our third team member, who seemed particularly on edge. Eventually, she told us with some embarrassment that it felt as if there was a fourth person with us. She couldn’t explain why. Svensen remarked that the same thing happened to Ernest Shackleton and his companions as they made a desperate walk to Stromness, a whaling station in South Georgia, to get help for their stricken exploration party. I knew of that tale too, but I didn’t feel a presence so much as a dread that something terrible was happening which we did not understand. 14

That night the gales returned with force, rattling our ship to its bones, howling through the vents as the ice pressed in hard against the hull. The captain sent out an SOS, although nobody could reach us, not in this storm, not this far north. On the third day, the radio died and our ship lost all communications. But for the American container ship concealed behind the whirling blizzard, we were alone at the end of the world. With horror, it dawned on me that I was stuck on a vessel embedded in an ice floe on a planet in the gravitational grip of a sun that turned in the Milky Way within a universe held together by dark matter. I was trapped. We all were. And we always had been. As I looked out at the ice floe, I felt nausea at the sudden awareness that I was glued to an incomprehensibly large and unknowable object, like a gnat stuck to a tractor wheel. It moved regardless of me, unheeding of my feelings. Unaware, even, of my existence.

To try and take my mind off things, I played poker with Svenson and Wilkinson in the recreation room, but we couldn’t relax. Not when we heard rumours regarding the latest discovery in the lab. Those mysterious deposits found on the container ship were undoubtedly, irrefutably, almost certainly – it was said in hushed gasps - human skin. The captain assured us that as soon as the storm passed we would cut our way free and return home. But this directive was soon to change. New calls of alarm rippled through the Salvo when it became evident that someone was on board the trapped American container ship, after all. We could see it with our own eyes through the spiralling snowflakes. Lights beamed from the tilted deck of the Witness. It was astonishing. Some crew members claimed they saw shadows 15flit in the windows. We speculated that the crew, or whatever was left of it, had been in hiding from our rescue team when they boarded earlier. But why?

It took another day for the weather to give us a second chance to cross the ice to inspect the stricken vessel. Nervously, I watched Davydkin’s team file across the snowdrifts until they disappeared into the murk. When they didn’t return within twenty-four hours, a second party went out to investigate. They didn’t come back either. The only thing that returned was a second storm which obliterated our view of the Witness and trapped us inside our own vessel, shaken by booms of thunder, the likes of which I’d never heard at sea.

The captain held an emergency briefing with his highest-ranking officers while the rest of us tried to carry on with our work. But panic had turned the mood. There was palpable tension in the canteen. At dinner, the usually level-headed Pokrovsky, leader of the biological analysis team, unleashed an extraordinary outburst. He clawed at his own cheeks and neck. Shrieked something about it getting under his skin. When Chung tried to calm him down, he flung himself upon her, biting and scratching. It took three crew members to drag him off her and confine him to his cabin. As an emergency measure, it was decided that the scientists should relax for the night. Down tools. Read in bed. Watch some movies. In the morning the captain would announce a plan. In the meantime, my team would continue our rounds as usual, ensuring the ship was safe.

Inside the Salvo, all was well, structurally speaking, despite the battering winds and shifting pack ice. Svensen, Wilkinson and I found nothing amiss. But it was when we 16braved the deck that we saw something out on the ice, a darkness against the white, expanding and shrinking like a lung. Through binoculars I could make out a giant, slug-like shape. A walrus, suggested Svenson, but it couldn’t be. This had no discernible mouth, flippers, nor any consistency to its size and shape as it writhed slowly closer. I assigned a nightwatchman to keep track in case it tried to breach the hull, but he told us the next morning that the beast had seemingly plunged directly down into the ice. That was impossible, but we could see in the murky daylight that it had gone, leaving only a long, meandering red strip, marking its movement. Blood, we thought. Perhaps it was a walrus after all, wounded by our bow.

Wilkinson and I braved the gale to go onto the ice and check. ‘This isn’t blood,’ said Wilkinson, dabbing and sniffing at the red smear, ‘this is something else.’ We hacked away a chunk and took it back to the ship for the biologists to test. But the lab was locked. Chung, deeply affected by the missing rescue teams and Pokrovsky’s attack the previous evening, had suffered a breakdown, we were told. Crying, wailing, ranting about pain in her skin. She too had been confined to a cabin. As had several more of their team, all in states of distress, marked by outbursts of vitriol and violence. Others, including coastguard crew, lined up to see the doctor, complaining of rashes, nausea, stomach ache. Scuffles broke out in the corridor as they grew impatient and aggressive. We could only find one scientist willing to look at our hunk of stained ice. He had no doubt about what the red substance was.

‘Spores,’ he said, scratching his arms. ‘Those are spores.’

It was hard to know what to do for the best. There were not enough remaining coastguard crew who were in the 17right state of mind to deal with the escalating situation. The labs had shut down. There were no scientists left to talk to. Nobody was interested in finding the cause of our woes. It was enough effort simply to keep order from breaking down entirely.

At breakfast the next morning, Wilkinson solemnly showed me her fingernails. They were green with fungal growth. Her toes too. Everything itched. She had this urge, she said, to leap out onto the ice to freeze it off, to cleanse herself. I told her to stay calm, see the doctor immediately, get some treatment for the disease now while she could. At this her face soured. She let out a scream, grabbed a fork like a dagger and came at me across the table, her teeth bared. ‘It’s you,’ she said, ‘you’re the disease.’ Two crewmen grabbed her and dragged her kicking to her quarters, where they locked her inside.

Svenson and I did our rounds that day without Wilkinson, trying to ignore the clamour of distressed voices echoing down the corridors, as the incarcerated rattled the doors of their locked quarters and cried out for release.

‘We are thirsty for light!’ pleaded Pokrovsky.

‘The itch,’ screamed Chung, ‘it’s unbearable. Take it off. Let me out of it!’

It was so sad that Wilkinson had been infected by the malady spreading through the Salvo. The signs were there, I supposed, when she’d told us the other day of her uneasy feeling that we were being stalked by invisible entities. Svenson shook his head. ‘I don’t know about you,’ he said, ‘but I have this eerie feeling that someone else is here with us. A presence. Can you not feel it?’

‘Feel what?’ I said. 18

‘As if we are more than what we are.’ Svenson frowned, seemingly confused by his own words. ‘That we are legion.’

‘Oh God, not you too.’

When we reached the bridge to report to the captain, we found him alone, staring out over the ice, a tumbler of whisky in his hand. More of the crew had succumbed, he told us, to whatever it was – mass hysteria or infectious disease, he knew not which. It had been the scientists, mainly, at first. But now his deck officer and chief engineer had gone stark raving mad. As soon as this storm abated, the captain promised, we’d leave this place.

But what kind of place was this? I wondered. It was a block of ice moving in a body of water on a spinning globe in the blackness of space. What place were we thinking of leaving? And where, precisely, were we planning to flee? There was nothing but the world and we were inescapably of that world. It was outside and inside us. Microbes thrived in our bodies, digesting our food, defending our immune systems, transmitting signals to our brains. They were in the sea. On the land. In our cities. In our water supply. Beneath the ice of the Arctic, blooming and mutating, seeping up into the light. There was nowhere to go but here, and here was everywhere.

That night, Svenson woke me up as he clattered down from his bunk, furiously scratching his stomach. ‘I need to see Wilkinson,’ he muttered, swiftly exiting in only his T-shirt and underpants. Groggy from sleep, I became aware of a commotion outside. Yelling and screaming. The slam of doors. I pulled on some clothes and a jacket and left the cabin. A terrified Russian cook ran past me. ‘They’re out,’ he yelled. ‘They’re getting out.’ 19

I hurried after him as he hurtled down the steps, into the kitchen where there were staff huddled together by the ovens, clutching an array of sharp implements. The situation had escalated, it seemed. So many crew members had become gripped by the madness that it became impossible for those who remained sane to contain them. Now the infected were opening the doors of locked cabins, letting people out, and all hell had broken loose. Some were even escaping from the ship and heading onto the ice, heedless of the wind and snow, to face their certain deaths.

Wilkinson. I had to find Wilkinson.

Grabbing a long knife from the rack, I left the kitchen and made my way through the ship in search of her, hiding from the occasional crew member as they hurtled past in the grip of their mania, half-dressed or even naked. I checked in the empty cabins of the infected to see psoriatic flakes of skin piled on the furniture and the bedding shredded. As I feared, Wilkinson wasn’t in her quarters. There were smears of blood on her sheets and something scratched into the metal of her bunk in a spidery scrawl:

WE ARE THE DISEASE

As I headed to the main deck, I spotted Svenson in his underwear, running up some stairs, his screams less those of pain and more a kind of war cry. I called out his name and he turned briefly, eyes wild, then sprang from view. I hurried after him onto the deck but he had vanished. It was hard to make out anything clearly in a darkness obfuscated by snow, but in the shimmering lights of the Salvo I saw a figure below. It was Wilkinson, or the top half of her, 20anyway, embedded in the ice, clad only in a T-shirt. She steadily and rhythmically paddled her arms as if wading, waist deep, against fast-moving water. Luminescent algae streamed up through the cracks in the surface around her midriff, turning her exposed arms and neck green, illuminating her face, stricken with a combination of terror and ecstasy.

‘Wilkinson!’ I cried out. ‘Ellen!’

I thought for a moment she could hear me. Her head tilted at an angle, mouth opening as if to speak, and out poured a column of black, viscous matter. It kept coming and coming, thickening into a black coil around her torso, expanding and contracting. Breathing. I staggered back with a cry. Behind me there was a loud click as the door opened and the captain emerged, uniform in shreds, shocked momentarily by the blast of wind, looking frantically around him as if for an escape. I raised my quivering knife in defence, and he came rushing at me in a fury, then flipped over the edge. I didn’t peer down to see what happened to him, because other figures on deck were moving erratically in my direction, barking nonsensical gibberish. I lost my nerve and I fled.

We cannot stop them. All that we thirteen remaining, uninfected crew members can do is barricade ourselves into the kitchens, where there are supplies of food and knives behind heavy doors. Here we must wait out the storm. At night, the ice pushes so hard against us it feels as if the ship will split and take us down into the infested depths. Despite the gale howling through the vents and rattling the gantry we can hear them, the sluggish entities that crawl up the hull and seethe on the upper decks, 21releasing spores into the wind. They drone and weep and seep their strange microbial cacophony into my thoughts. Even when I put my fingers in my ears, the noise roars within me, through the rivers of my blood, in the forests of my gut flora, across the teeming oceans inside my cells. The sound is outside and inside and nothing makes a difference. It will never go away. It feels like there’s a coating of slime on my skin. I cannot see it, but I know it is there. I have the urge to tear it off, rip myself out of myself, become something other, something not of this world, of this universe, this waking nightmare. But I don’t tell the others. If they find out, they may kill me or eject me from the ship.

As a last resort, I have taken to scribing this private journal of events, which, I suspect, will be the only evidence left on board the Salvo of what has occurred. A written legacy left to whatever remains of humanity, for as long as it lasts. Our only hope is that we thirteen are somehow immune, that the gales die down and we can steer this ship free with a skeleton crew. In that unlikely event, we will have to abandon our friends and colleagues on this frozen plateau, to the mercy of the algae bloom, and to each other. In the darkest hours, we can hear them outside, whooping and screaming, hurling obscenities at the stars, and we are so afraid.22

When Nature Calls

Maleeka opened the back door of their bungalow to discover that their water butt had vanished. The vegetable patch was still there. The electricity generator and greenhouse, too – just about – but where the butt had been was now thin air. Carefully, she dropped to her knees and crawled to the cliff edge. On the shore, thirty metres below, the big green container poked from a pile of rubble, topped with bits of lawn. It was getting dark. Dirty clouds amassed over an English Channel that was rising quickly, drowning rocks and turning the sandstone blood-red. Tonight’s full moon meant the tide would be extra high. After a week of heavy rain, who knew what else they might lose before the morning? 24

She returned to the kitchen to tell Rizzie. At the news, Rizzie suddenly looked much older than her sixty-seven years. ‘Have we any water bottles left?’

‘I filled one earlier,’ said Maleeka.

‘Then we can have a cuppa, at least.’ Rizzie opened the cupboard above the kettle and stared into it for a while. Finally, she said, ‘Where’s the tea?’

‘I think we finished it.’

Rizzie sighed. ‘Then there’s nothing to be done. Nothing.’

‘You should have said.’

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: