Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Cliff Hardy Series

- Sprache: Englisch

The forty-first book in the Cliff Hardy series Legendary PI Cliff Hardy has reached an age when the obituaries have become part of his reading, and one triggers his memory of a case in the late 1980s. Back then Sydney was awash with colourful characters, and Cliff is reminded of a case involving 'Ten-Pound Pom' Barry Bartlett and racing identity and investor Sir Keith Mountjoy. Bartlett, a former rugby league player and boxing manager, then a prosperous property developer, had hired Hardy to check on the bona fides of young Ronny Saunders, newly arrived from England and claiming to be Bartlett's son from an early failed marriage. The job brought Hardy into contact with Richard Keppler, head of the no-rules Botany Security Systems, Bronwen Marr, an undercover AFP operative, and sworn adversary Des O'Malley. At a time when corporate capitalism was running riot, an embattled Hardy searched for leads - was Ronny Saunders a pawn in a game involving big oil and fraud on an international scale? Two murders raised the stakes and with the sinister figure of Lady Betty Lee Mountjoy pulling the strings, it was odds against a happy outcome.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 242

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Thanks to Jean Bedford, Miriam Corris,

Tom Kelly, Jo Jarrah and Angela Handley.

First published in 2016

Copyright © Peter Corris 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 588 0

Internal design by Emily O’Neill

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Emily O'Neill / Lisa White

Cover image: Lori Andrews / Getty Images

To the memory of my parents,

Thomas Corris (1913–1967)

and Joan Kelly Corris (1913–2013)

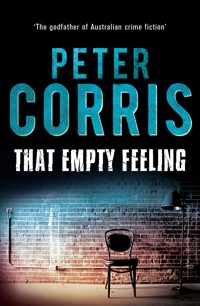

Hell is empty, and all the devils are here.

—William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Contents

part one

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

part two

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

part three

25

26

27

28

29

30

part one

1

I was sitting on the balcony of my daughter Megan’s flat turning over the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald and trying to decide if I liked its new tabloid format. They called it a ‘compact’ but I prefer to call a spade a spade.

I decided I didn’t care one way or the other—the paper was mostly gossip and stories that didn’t matter much now and wouldn’t matter at all tomorrow. I turned to the obituary page and almost dropped the paper.

‘Shit!’

Megan appeared at the sliding door. ‘What now? They’re bringing back the death penalty?’

‘Barry Bartlett’s dead.’

‘Who’s Barry Bartlett?’

I gazed out at Camperdown Park across the street. It was mid-morning in early spring; all the benches were occupied and people were sprawled on the grass, some already unwrapping their lunches. Barry had always enjoyed his lunch.

‘It’s a long story,’ I said.

Megan came out and eased herself into one of the cane chairs. She was eight months pregnant. It hadn’t been planned but she was happy about it. So was her partner Hank and their son Ben, my grandson. Ben was five and looked a lot like me—tall and dark with a hooked nose and a low hairline. He wanted a sister and you’d have to hope that if she came along she’d look like her mother rather than her grandad. Megan, in her late thirties, still turns heads. She looks a bit like Sigourney Weaver with a few more kilos.

‘Cliff,’ she said, ‘Ben’s in school, I’ve done the housework, prepared our lunch and I reckon it’s just about time for a drink. I’ve got nothing to do until 3.30. I wouldn’t mind a story.’

Megan’s partner is an American. She’s picked up expressions like ‘in school’ and they watch gridiron on television. She ran her hands over her swollen belly.

‘Sure it’s not twins?’

They’d decided they didn’t want to be told the sex of the child but they knew they weren’t getting twins.

‘It’s not fucking twins, as you well know. Just a big lump like Ben—and you, probably. What were you when you were born?’

‘Nine pounds something, I believe. Don’t blame me. Hank’s a bit bigger than I am.’

Megan groaned. ‘I can see the stretch marks. I’ll get you a beer and you can tell me all about Barry what’s-his-name. Take my mind off thoughts of the delivery suite.’

She brought the beer and I drank most of the stubby before saying anything. Megan looked enquiringly at me.

‘What?’

‘It’s not something I like to think about.’

‘Not your finest hour?’

‘Not by a long shot. I opened a file on it but in the end I didn’t put anything much in it. I just left it pretty empty. Empty . . . the whole thing had an empty feeling.’

‘Probably do you good to get it off your chest.’

2

Barry Bartlett was what the media called ‘a colourful Sydney identity’, which means that he was a crook who had stayed out of gaol for more than twenty-five years. His English family had migrated to Australia just after the Second World War—Ronald and Irene Bartlett, Barry, his sister Milly and his brother George. Barry was in his early teens then.

‘I was a terror on that ship and no mistake,’ he told me.

This was close to thirty years later, when I first knew him. He’d been a Balmain tearaway who’d left school early, worked for bookies and light-fingered wharfies and done eighteen months in Long Bay for assault with menaces in his late teens. Nothing since. He’d branched out into big-time fencing, illegal gambling and nightclub ownership. He also managed a few boxers. An Aboriginal fighter I knew, Bobby Munday, introduced us.

Bobby went on to have a successful career and have his money honestly managed and invested by Bartlett, which was a very rare thing then and since. I sat with Bartlett at a few of Bobby’s fights. After we watched him just squeak a points decision defending his Commonwealth welterweight title, Bartlett phoned me.

‘That cunt Simmonds wants to buy Bobby’s contract and put him in against Sugar Ray Leonard in Vegas.’

‘Jesus,’ I said.

‘Bobby’s not in that class and never was, plus he’s near the top of the hill if not fucking over it, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I know you’ve got influence with him, Hardy. I won’t sell his contract but those things aren’t really worth a pinch of shit. Simmonds could find a lawyer to get Bobby out of it. There’d be one hell of a big pay night and Simmonds and the lawyer and some fat prick in the US’d get the lion’s share and Bobby’d end up with brain damage or worse. I want you to convince him not to do it.’

‘A lot of money to pass up.’

‘He’s got a lot of fucking money.’

This was well before the days of email. Bartlett had the accountant he’d put in charge of Bobby’s affairs fax me over details of Bobby’s bank accounts, investments and tax status. As things stood, Bobby was set for life, with enough coming in from investments to live on and capital to invest in other enterprises of his own choosing. His life and that of his wife were insured; there were tax-friendly trusts set up for his two kids.

I phoned Bartlett. ‘I should have had you manage me.’

Bartlett laughed. ‘Bobby had some big fights at the right time. That’s how he got the world ranking. I wrung money out of the fucking media every time they wanted him to say two words. That doco brought in a motza. What’s the most you ever made from a case?’

‘Okay, point taken, but you know fighters. They don’t know when it’s over and they don’t like to be told.’

‘I’m asking for your help. Might sound fucking weird, but I’m proud of what I’ve done for that boy. Makes me feel I’ve given something back to this country that’s been so good to me.’

I laughed. ‘Blarney—I thought you were a Pom, not a Mick.’

‘Call it what you like. I’ll pay you . . .’

‘Shut up, you’re not getting the bloody moral drop on me. I’ll do what I can. The last thing I want to see is Bobby on the canvas in Las Vegas and Teddy Simmonds counting the money.’

I rang Bobby and asked if he could spare me some time. Me being a private detective amused him, and he was usually pleased to see me to talk boxing and make jokes about trench coats and .38s. Didn’t matter that I didn’t own a trench coat and my Smith & Wesson hadn’t seen the light of day for quite a while.

I dropped in at Trueman’s gym in Newtown and caught the last of Bobby’s sparring session. He had a massage and a shower and we went out onto King Street.

‘Fancy a beer?’ I said.

‘Are you kidding? I’m strictly off it.’

‘Why’s that, champ?’

Bobby shot me a look. He wasn’t dumb. He knew of my acquaintance with Bartlett. ‘Oh, shit,’ he said. ‘You’re going to tell me Teddy Simmonds is a bigger crook than Barry and not to listen to him.’

‘Not a bit of it. You’re not a child. You can talk to whoever you like. I just want to show you something. Where’s your car?’

Bobby had a Beemer convertible he was proud of and happy to demonstrate. It was parked nearby and we walked there with him nodding graciously to people in the street who knew him.

‘Pretty sharp, eh?’

‘The car? Yeah.’

He laughed. ‘Fuck you, Cliff. The sparring.’

I grunted. ‘Not too shabby. Want you to meet an old mate of mine, Phil Sikes. Lives in Watsons Bay.’

Like all professional athletes, Bobby had trouble filling in the time when not training or performing. He was a family man but his wife, Jenny, handled that part of his life and Bartlett’s accountant dealt with the business side. He read a bit, mostly biographies of the well-known. He liked the movies and TV and did some work with the Aboriginal Youth Program but he didn’t play golf. Time hung heavy and he was happy to go for a drive.

Phil Sikes was an ex-featherweight. A main event fighter in an unpopular division, whose career went nowhere. He won a lottery, retired and kept himself busy and amused by showing boxing films to sporting clubs and charity organisations. He had the best collection of boxing films in Australia and kept up to date via arrangements with US and European television providers and boxing managers and promoters.

Phil shook Bobby’s hand enthusiastically. ‘I’ve got a few of your fights. You had a great left hook.’

Bobby beamed. ‘Still have.’

Phil nodded. ‘Cliff here did pretty good as an amateur but didn’t have the heart for the real game. He wanted me to show you something.’

We went into Phil’s viewing room and he pulled down the blind to block the million-dollar view of the water and the boats. He had a huge TV and video set up and he handled a couple of remote-control devices like a chessmaster setting up the board.

Over the next two hours we watched films of the career of ‘Sugar’ Ray Leonard, then the undisputed welterweight champion of the world. Phil had somehow spliced together a sequence of films that ran from Leonard’s defeat of Cuban KO artist Andrés Aldama to win the gold medal in the welterweight division at the 1976 Olympic Games through his early professional career, where he won a succession of fights, to his contests with Roberto Durán and his defeat of Tommy ‘Hitman’ Hearns.

Interspersed were extracts from documentaries on Leonard—his background, physical characteristics, training, tactics, techniques. No one said a word as we watched Leonard mature from a spindly cutie to a fighting machine. Leonard’s reach was ten centimetres greater than his height and, as with Les Darcy, it let him do damage from a distance without extending himself and left him with abundant power when his opponent, tired of eating leather, was slowed down and easy to hit.

Phil and I had a couple of beers while watching the screen. Bobby refused at first but accepted during the Leonard/ Hearns fight.

‘Moves well,’ I said when the screen went blank.

‘Never stops,’ Phil said. ‘No, he stopped against Durán and lost. Learned his lesson.’

‘What about Hagler?’ I said. ‘Marvelous’ Marvin Hagler was the world middleweight champion, a powerhouse puncher.

‘One day,’ Phil said. ‘Be interesting.’

We thanked him and Bobby was quiet on the return drive, which he made cautiously. I’d left my car at the gym and he dropped me there.

‘I get the point, Cliff. He’d kill me.’

‘Possibly.’

‘You see that left jab?’

I shook my head. ‘Not really.’

‘Exactly. Thanks, Cliff.’

3

Bobby Munday defended his Commonwealth title against an up-and-coming Maori fighter in Auckland and took a pretty heavy beating before rallying and knocking the Maori out in the tenth round. Then he retired.

Barry Bartlett bought me a drink when the retirement was announced and thanked me for helping Bobby see straight. Then I didn’t hear anything from him for a long time. He stayed out of the courts and the papers and, with all my other concerns, I more or less forgot about him. So I was surprised when he phoned and asked to see me.

I was still in Darlinghurst then, although the gentrification wave that would move me out was building. Some of the streets had been blocked off to divert traffic and provide a quieter atmosphere and the building next to mine was being demolished, to be replaced by a block of upmarket flats.

Like Bobby, Barry found it amusing to know a private eye and he’d dropped in a few times in the past to give me a ticket to a fight or just to talk boxing.

He turned up on time. His usual style was to pour scorn on any décor that wasn’t brand spanking new—I had nothing that was—from car to clothes, but he was subdued as he lowered himself into my battered client chair.

He sat silently for a minute and I opened the bidding.

‘How’s Bobby doing? Haven’t seen him for a while.’

He roused himself. ‘Who?’

‘Bobby Munday, the bloke we saved from brain damage.’

‘Bobby, oh yeah. He’s doing fine. Healthy financially and otherwise thanks to you and me.’

‘How’s he occupying himself?’

‘He’s the fitness coach of the fucking Sydney Swans. He reckons his son’s a champion in the making. Poofter game if you ask me, but there it is.’

‘So that’s not why you’re here.’

‘No. Fact is, I’m very fucking confused.’

‘Barry, I know you’re ruthless and a bloody chancer, but I’d never have picked you as confused.’

Bartlett was a big man—over six feet and sixteen stone at least. He’d played rugby league and been a wrestler when young and some of the muscle had turned to fat. His colour was high, suggesting hypertension, and it rose as he half stood. ‘You’ve got a fucking nerve talking to me like that. What’re you? A two-bob keyhole-peeper. You . . .’

He slumped back into the chair, out of breath and out of anger. The hard lines of his craggy face sagged as if he’d lost a lot of weight lately. Jowls well on the way. His forehead under the receding hairline was damp and he mopped it with a handkerchief he pulled out of his pocket. His voice emerged on a breathy wheeze.

‘Shit, I’m sorry, Cliff. I’m not meself.’

I had a bar fridge in the office. I opened it and took out some bottled water. I had a bottle of Black Douglas scotch in the deep bottom drawer of my desk and paper cups. I made a couple of mid-strength drinks and passed one across to Barry.

‘Have you got medication for that blood pressure?’

‘Yeah. And for everything else.’ He took a long swallow and managed a short-winded laugh. ‘Truth is the old ticker’s not too hot. Waiting for the results of some more tests, but it doesn’t look great. The quack says the best treatment is to avoid stress. How do I do that if I’m being conned?’

‘Who by?’

He tossed off most of his drink. ‘Fucking direct, aren’t you?’

‘Only way to go, mate. If you’re going to be a client you have to stay alive long enough to tell me the problem and pay me a retainer. Unless you get a grip on yourself there’s no time to lose.’

‘You’re right, you’re right.’ He put the paper cup with only an inch or so of fluid in it on the desk and pushed it away. A self-denying gesture of sorts. I took a solid belt of my drink.

Barry mopped his face again and leaned forward, lowered his voice. ‘Here’s the thing, mate. I was married—well over twenty-five years ago, now. It didn’t work. I still rooted every woman I could get my hands on and my wife left me after a few years. There were two kiddies—a boy and a girl. I hardly knew their bloody names, I was so busy making a quid and staying alive.’

It was typical of people like Barry to flavour explanation with a touch of apology and a stronger touch of self-justification.

‘Anyway,’ he went on, ‘she took the kids back to England—she was a Pom like me—and divorced me. She didn’t ask for maintenance or anything and that was the last I heard of her . . . and them.’

‘Until?’ I said.

‘Yeah, until this kid turns up claiming to be my son. His name’s Ronald Saunders and he says he was adopted by Sylvie’s—that’s the wife’s name—second husband and took his name.’

‘Has he got any proof he’s your son?’

‘He’s got a couple of photos of Sylvie holding a baby he says is him.’

‘No birth certificate?’

‘He left it back in the UK. He’s applied for a copy, and the adoption papers.’

‘What about a passport?’

‘He’s got that. British. So he must’ve had a birth certificate.’

‘Nothing from his mother and stepfather?’

Barry shook his head. ‘Both dead in a car accident. Showed me a newspaper clipping.’

‘What about the sister?’

‘Um, Barbara. He says she left home when she was sixteen and he thinks she’s on the game in London. They’re not in touch.’

‘It’s conveniently vague,’ I said. ‘What makes you think it’s true?’

‘Three things. He’s the spitting fucking image of me when I was that age and he’s got the same in-your-face attitude.’

I had a fair idea from his behaviour what the answer would be but I asked the question anyway. ‘What’s the third thing?’

He drew in a deep breath. ‘I want to believe it. I’ve had a rackety life. I’ve got a lot of . . . competitors and no real friends. Haven’t had a relationship with a woman for years. I’ve just used professionals and that’s a fucking lonely life.’ He looked embarrassed and fiddled with his cuffs. ‘And . . . if I’m on the way out, I’d like to think there was someone to keep things going. Someone close.’

I nodded. ‘What does this Ronald want?’

‘Ronny? Nothing. He just wants to work for me, with me.’

‘Learn the criminal trade, as it were?’

‘I know you like taking the piss, Hardy.’

Hardy now, I thought. What happened to Cliff and mate?

‘I’m a legitimate businessman these days, more or less. A developer, an entrepreneur, as they say. I could use someone I could trust and hand things over to. Even if the heart stuff ’s fixable, I’m not getting any younger. And I make no bones about it: I’m a lonely man.’

‘Okay.’

He looked around the room—at the windows, the crumpled venetians, the dented filing cabinet and at me.

‘You’re not doing so good,’ he said. ‘I’m offering you work and you’re coming the high hat.’

‘I said okay. Tell me what you want.’

‘I want you to investigate him. Meet him, weigh him up, talk to him. Then see what he does, where he goes, who he meets.’

‘What if he’s not who he claims to be—or if he gets pissed off at being investigated?’

‘I’ll have to take that chance, but if you’re as good as you’re cracked up to be, he’ll never know you’re checking.’

Flattery now, I thought. Oscar Wilde said the flatterer is seldom interrupted, but Barry stopped right there and I had that sense I get with a lot of clients, probably most. There was something he hadn’t told me.

‘Ronny showed up a few months ago. I liked him. Couldn’t help it. He’s likeable. He needed money so I gave him a few little jobs to do and paid him. Nothing much.’

‘Nothing much of a job, or nothing much of money?’

‘Both. So he knows some of the things I do.’

‘Like?’

‘Shit, paying off politicians and officials to steer things my way. Everyone does it. It’s still the only way to do business in this town.’

I shook my head. ‘It’s the quickest way maybe, or the easiest, but it’s not the only way.’

He became aggressive again. ‘Listen, this is something you wouldn’t understand at your level. You borrow money to get things done. At interest from people who charge an arm and a leg and are fucking impatient. Every day you run over your date to pay back eats you alive. So you have to speed up development decisions, rezonings, environmental reports, permissions . . .’

I did understand it. I understood that it meant the money providers got heavy with the borrower and the borrower got heavy with the people he was buying. And other people got heavy with them. It wasn’t a world I wanted to get into.

He read my mind. He leaned forward, picked up his drink and drained it. ‘Like I said, I’ve got . . . competitors and there’s things I don’t want certain people to know. I’m worried that Ronny might be a plant.’

‘Suppose he is, what then?’

‘Nothing. I’m disappointed and I piss him off. That’s all.’

‘What if I find out he’s a con artist and who put him up to it?’

He opened his hands. ‘Then I know the score. I’m a winner and so are you, Cliff.’

4

I didn’t have many qualms about working for someone like Barry Bartlett. As far as I knew he’d never killed anybody, and I’d worked for lawyers and politicians who’d stretched the laws to breaking point and beyond. Sometimes it was a hard line to draw. This sounded more or less like a personal problem, although Barry’s mention of people he called his competitors (colour them enemies) sounded a warning note. But he was right about my financial situation; the windows needed cleaning and the venetians needed to be replaced.

I had him sign a vaguely worded contract and pay me a retainer. He gave me an address for Ronny Saunders and the registration number of the company car he was driving.

‘Have you checked him out at all yourself?’

‘Nah. Didn’t have the energy. And there seemed to be plenty of time, then. Thought about it, but . . . Then I remembered you.’

I said I had a few things to clean up first before getting started.

‘That’s okay,’ Barry said, giving me his card. ‘BBE is having a drinks party at my offices the day after tomorrow. Ronny’ll be there. You can kick off then. You’ll see some familiar faces.’

‘BBE?’

‘Barry Bartlett Enterprises.’

‘Of course.’ I remembered occasionally seeing Barry’s picture in the society pages of the magazines they kept at my doctor’s surgery, but the name of his business hadn’t really registered.

He tossed his cup at the waste-paper bin. It hit the rim and fell in. ‘Till Friday. Have a shave,’ he said. ‘Bring a woman, if you like, and wear a fucking suit.’

I did have a couple of things on hand—finishing up on a dodgy car insurance claim and the vetting of a company’s security system, which involved trying to beat it and could be fun—but I intended to spend some of the time checking on Barry Bartlett himself. The fortunes of people like him rise and fall and where he was in the cycle could have a bearing on the job he’d assigned me, and particularly on my chances of being paid.

I knew Barry had made money through the use of a stevedoring company and a number of corrupt customs officials in the past. If you could circumvent the payment of import duties and penalties on certain cargoes you could provide the market with cheap goods about which no questions would be asked. As far as I knew this operation hadn’t involved drugs. I made some phone calls to check on the current state of play. I didn’t trust that Barry had told me everything.

I spoke to a couple of wharfies in pubs and a ‘retired’ customs officer in a Darlinghurst bistro and learned that Barry, like this guy, had got out of that business just before a Royal Commission and a crackdown.

Jimmy Cook, a financial journalist, told me that BBE was a middle-to-heavyweight player in Sydney’s ever-increasing development scene these days, making sensible bids for projects and so far delivering results on time.

‘What about union problems, cash-flow hold-ups, that sort of thing?’ I asked.

I could hear Cook expel smoke as he spoke. ‘Clean bill of health. Let me know if you hear any different.’

‘Bullshit!’ Harry Tickener said the next day when I gave him Jimmy Cook’s assessment of Barry Bartlett’s current business status.

Harry was an old friend who’d worked for almost every newspaper ever published in Sydney and had been fired by most of them. He ran a newsletter called Sentinel with the logo ‘We Name the Guilty Men’. He did, too, and he spent almost as much time fighting libel writs as collecting information and writing his exposés. Sentinel had some backing from a couple of radical unions and individuals, got some advertising from a left-wing community radio station and depended to a large extent on volunteer labour. I’d done some pro bono work for Harry myself.

Harry put his sneakered feet up on a desk of about the same vintage as mine and scratched at the fringe of ginger hair he retained. ‘Barry Bartlett’s got his finger in some very dirty pies but he wears thick gloves.’

‘Good writing,’ I said. ‘Have you had a go at him?’

‘No, he’s got that shyster Todd Silverman in tow and I’ve just got clear of a slander action that would’ve finished me if it hadn’t fallen over at the last minute. I don’t need Silverman up my arse.’

At that time, Harry ran the operation out of a small terrace house in Macdonaldtown—two down, two up, no room to swing a cat anywhere. The room that served as his office had space for his chair, a desk, two filing cabinets and a stool. Otherwise every surface was covered with paper, every cranny was packed with books and files. I squatted on the stool with my knees lifted nearly to my waist. A couple of flies buzzed around looking for somewhere favourable to land.

‘What sort of pies?’

Harry took a no-frills can of insect killer from a drawer in the desk and zapped the flies. Then he sneezed violently.

‘Shit, I’m allergic to that stuff.’

I said, ‘You need a low-allergy spray.’

‘I need a lot of things I haven’t got. Bartlett’s development operation’s legitimate enough as those things go, but it’s partly a front.’

‘For?’

Harry waved his hand at a pile of manila folders. ‘I wish I could say I’ve got evidence like the stuff in there—statements, analyses, statistics—but I can’t. There’s something big, very big, behind what Bartlett does. You get hints from the names of people he employs, from the overseas trips he takes and the things he invests in.’

‘Like?’

‘Trucking companies, cruise ships, mineral exploration. Rumours of something to do with oil.’

‘Profitable concerns, surely. Australian business on the move.’

‘Yes, but with no discernible connection between them. In that kind of business it’s an economic imperative that one hand shakes another. I’m certain there is a connection and it’s a good bet that it’s very dodgy. I’m not even sure Bartlett knows what’s really going on himself.’

‘That’s vague. I can see why you haven’t written anything.’

‘Not yet. I’m thinking about it. So he’s offered you a job, has he?’

‘Come on, Harry. Not in the way you imply. I gave up working for other people long ago. He wants me to investigate something personal.’

‘Are you going to do it?’

‘I need the work.’

‘If I weren’t a friend of yours I’d ask you to keep your eyes and ears open for me but I won’t. I know you’ll play it straight for as long as you can.’

‘That’s not a vote of confidence.’

‘You’ve got some sort of obligation to Bartlett, haven’t you?’

‘Not exactly. He did the right thing by someone he could’ve exploited. I respected that.’

‘Hitler was good to his dogs. Just be careful, Cliff. Be very careful.’

‘It’s a personal thing,’ I said, knowing that it might not be.

‘Nothing’s personal,’ Harry said, ‘not entirely.’