4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Altus Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

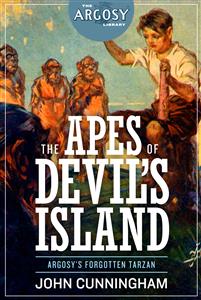

When Jimmy Wendell takes a yachting trip with some friends, he never expected to become involved in an attempted murder of the crew and the ship's destruction on a reef. Making it to a small, shark-encircled island, Wendell will soon learn of the ape inhabitants of that mysterious land.... Argosy often revisited the themes from their most popular stories, and this is no different: author John Cunningham pens a tale of high adventure that has been forgotten for too long.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

The Apes of Devil’s Island

by

John Cunningham

Altus Press • 2018

Copyright Information

© 2018 Steeger Properties, LLC, under license to Altus Press

Publication History:

“The Apes of Devil’s Island” originally appeared in the April 7, 14, 21, and 28, 1923 issues of Argosy magazine (Vol. 150, No. 4–Vol. 151, No. 1). Copyright © 1923 by The Frank A. Munsey Company. Copyright renewed © 1950 and assigned to Steeger Properties, LLC. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Special Thanks to Janice Roberts

CHAPTER I

A MYSTERY

THE WIND that had tumbled down the cloud-burdened mountains and had rushed across the white-capped lake was howling and moaning under the eaves of my cottage. Two days ago the first frost had arrived, and the forests were now splotched with red and yellow. Before long that gay assemblage which had formed the summer colony at Saranac Inn would be dissipated to the four corners of the globe. It made me lonely to think of parting with all my friends of the summer: some I might run across in the city, others never see again.

As I looked out upon the wind-lashed September lake, I marveled at the contrast it offered to the quiet, balmy August lake. It was no more than three weeks ago that Eleanor Meredith and I had sat in a canoe, watching the moonlight play over the calm surface dotted with lily pads, with the dark shadows of the woods behind.

As she leaned back against the cushions, her white satiny dress had fallen gracefully about her slender body, offsetting the jet of her dark hair. It was not going to be easy to say good-by to Eleanor. Besides her good looks, she was a good sport and possessed an understanding nature. Her father and mother also were very pleasant, and I would miss seeing them. There were many others at the inn whom I had learned to like and with whom I would soon have to part. I looked out of the window, and sadly viewed the harbingers of winter. The telephone bell rang shrilly. Taking off the receiver, I heard Eleanor’s cheery voice.

“ ’Lo, Jimmy Wendell?” she called. “Father’s decided to go cruising in Florida for a couple of months, and wants to know whether you’d like to go, too.”

“Sure thing,” I answered. “Well, that is—I mean who is going? And when?”

“We’re all going,” she said. “Mother, Dad, Nicky and I. We’ll probably leave for Miami in about three weeks.”

“Great!” I answered. “Of course I’d be just crazy to go. Sure I’m not imposing? Say, who’s Nicky, or Micky, or whatever you called him?”

“He’s my brother; his real name is George. Dad says to come to the cottage and we’ll talk the cruise over.”

“All right,” I answered. “Be right over.”

The raindrops were still tapping at the window pane and the wind roared as raucously as ever, but somehow it now produced an effect of open hearth, chestnut-and-cider autumn, rather than of loneliness. It is strange what one little telephone bell can accomplish.

As I slipped into my raincoat and drew on my galoshes I marveled at the abrupt manner in which a tropical cruise had loomed upon my horizon. A matter which was equally astonishing was the fact that Eleanor had a brother. Queer I’d never heard him mentioned before, I thought.

And now you know why autumn found me at Eagle Crest, the Meredith’s home on Long Island. I was spending a week with them, and then we were all to board the train that would take us to Miami.

I believe that it is customary in books for the “I” character to give his pedigree, a more or less brief account of his infancy, childhood, boyhood, and all the other “hoods.” However, in my case it will be sufficient to say that I am very much like the rest of you, and have probably done, said and felt the same things you have. I was twenty at the time I am speaking of, and had just graduated from college. So much for “me.”

Now, nothing is better for the appetite than a brisk walk before breakfast. About the third day of my visit I came to the realization of this fact, and went for an early morning stroll in the large gardens. The dew sparkled on the grass, and the whole world smelled and looked its sweetest. Such surroundings are conducive to dreaming, and I fell victim to the spell. As I ambled along, plucking an unoffending shoot here and there, I painted bright pictures of the future.

However, I was soon deflected from this train of musing by the sight of a small figure bending over a table some distance ahead. I supposed it was Nicky. Although I had not seen him yet, I knew that he was at Eagle Crest. It struck me as a strange thing that he did not eat with the rest of the family; he certainly was old enough; twelve is a very advanced age for the nursery.

At all events, this was a good chance to make Nicky’s acquaintance, so I walked across the grass toward him. As I drew near it was evident that the boy was not aware of my presence; he could not hear my footfalls on the lawn, and was very much engrossed with something before him. Having a natural interest in children, I stepped up to within a couple of paces of him, and peered over his shoulder. To say that I was surprised would be putting it mildly.

I was almost shocked at Nicky’s occupation. There, pinned to the table, was a large horsefly. The little devil was engaged in a systematic devastation of its legs and wings; after each removal he would bend eagerly forward for a closer view of the struggles of the hapless fly. I admit I was fascinated by the proceedings, and determined to keep quiet and see them through. When no more limbs remained to be removed, the young scalawag proceeded with apparent gusto to twist the head from the mutilated body.

And then, while the miserable insect was still twitching, he snatched it up and carried it swiftly toward his mouth. He was going to eat it!

This was too much for me. Stepping forward, I knocked the fly from his clutch with a quick slap. The effect on him was as astonishing as it was unexpected. With a snarl the little body sprang aside and settled into a low crouch. His small face, with its beady eyes, was contorted by a malevolent frown. He made it very apparent how much my interference was resented, and awed me terribly by the savagery of his expression.

Then his aspect suddenly changed, and I beheld in front of me only a frightened boy. He appeared very natural and childlike as he hesitated a moment, and then said simply:

“Please don’t tell them. If you do, I Shall be punished.”

I assured the youngster that I would say nothing about the matter if he would refrain from such actions in the future. With that he turned and ran toward the house. As he hastened away I followed him with my eyes.

He was about the average size for a child of twelve, but I noticed that his arms were abnormally long, and dangled at his sides in a peculiar manner as he ran. When he disappeared from sight I returned to my walk, and marveled at the strange things children will do.

THE MEREDITH house—castle would come closer to describing it—was situated on a quasi cliff overlooking the Sound. The grading of the lawn had necessitated a concrete retaining wall which on the inner side was about three feet high; on the outer side it dropped sheer down for thirty feet, and was then hidden from sight by a dense tangle of trees and bushes. It became an after-dinner custom with me to sit on this wall with my coffee cup in hand, and chat with Nicky.

The little chap had quite captivated my heart, and it was impossible to reconcile myself to the fact that this affable little boy was the same being that I had seen one morning not long before. Through constant association with Nicky, that first picture I had of him was slowly fading from my memory. All the Merediths were in better spirits than I had ever seen them before, and could not get enough of Nicky’s company. I believe they were fonder of their son than any family I have ever seen. They treated him like a child that had just recovered from a hopeless illness. This idea struck me so forcibly that I asked Eleanor if Nicky had not been quite ill lately.

My question was met with a startled glance and an ejaculation. “Why? What makes you think so?”

It was so evident that Eleanor meant an emphatic negation that I thought it wise to let the matter drop by merely saying:

“He doesn’t look very strong. I thought it more than likely that he had not been well.”

In my talks with Nicky I found that he was very bright and interesting. His puckered little face and his dangling arms gave him a kind of fascination that kept him from becoming tedious like most boys of his age. I had not seen any more indications of a love of inflicting pain, and was beginning to think that Nicky had taken my advice to heart. However, my hopes were doomed to a disillusioning blow. It came about this way.

Having been so delighted with my pre-breakfast walks, I suggested to Eleanor that she accompany me. She fell in with my proposal, and for a couple of mornings we had walked about, getting our feet wet in the dew.

One morning as we ambled along, laughing and chattering about nothing in particular, I espied Nicky in the distance. The sight of him leaning over a table filled me with vague misgivings. I did my utmost to turn Eleanor in another direction, but I was unable; she insisted on going straight ahead.

Finally the inevitable happened, and she saw Nicky.

“Looks interested, doesn’t he?” she said with a mischievous smile; then added: “Let’s sneak up and see what he is doing.”

All I could say to dissuade her was of no avail. I contemplated coughing loudly, or making some commotion to attract Nicky’s attention, for I felt instinctively that he was about something forbidden. However, I remembered that Eleanor knew more about Nicky than I did; and besides, she was his sister, so I let her have her way, and we walked guardedly toward the stooping form.

This would be a splendid time for a great deal of morbid detail. But I think it will be enough to say that Nicky was literally tearing a live squirrel to pieces. The poor animal was tied down, and its mouth stuffed with a handkerchief to muffle its agonizing wails; its struggles were pitiful to see.

Eleanor burst into tears at the sight, and seized Nicky roughly. He was again as I had first seen him. His ugly, snarling face was covered with blood; he was fighting his sister and doing his best to tear himself free from her hold. Eleanor, however, was stronger than he, and it was apparent that his attempts would be useless. She turned her white face to me, and, pointing to the mangled squirrel, whispered:

“Put that out of its misery—and I’ll take this to the house.”

I BREAKFASTED by myself that day. When morning was fading into afternoon the butler informed me that the family were lunching in their rooms, and that I could have lunch wherever I wished. I chose the most unexpected place—the dining room.

The first company I had was at dinner. Dr. and Mrs. Meredith and Eleanor were at the table. They pretended to eat, but at best it was but a sorry meal. Dr. and Mrs. Meredith exchanged meaning glances, and Eleanor tried to make conversation with me. I was glad when the repast was over, and we went out on to the lawn in the cool of the evening for coffee. Eleanor and I sat apart on the wall, and for a long while were silent. She was the first to speak.

“It’s such a shame. He seemed to be getting along so well.”

No doubt my face showed my intense curiosity to know what it was all about, for Eleanor put her hands on mine and said:

“I’d like to explain things to you. They are so odd. Father says he is sure it is so, yet he doubts his own belief, and so far has told no one but the family.”

With that she sighed; then, turning abruptly on her heel, she walked slowly away toward the house, leaving me in the gathering gloom.

CHAPTER II

A BLOW IN THE DARK

OUR trip South was uneventful; the same old dirt, cinders, cards, and telegraph poles. However, there was one happening that should not be put in the category of the uneventful. This was Dr. Meredith’s discovery that an old medical school friend was on the train—a Dr. Grame. He was a big, intelligent, uncouth man, with baggy trousers and abrupt manners; but there was a charm and interest about him that attracted instantly.

In spite of his noisy blustering, he was, according to Dr. Meredith, one of the country’s greatest men in his line; but Dr. Meredith neglected to say what his line was. The two doctors spent a great deal of their time together, and when we were nearing our destination Dr. Meredith told us with satisfaction that he had persuaded his friend to accompany us on the cruise.

At Miami we put in a day shopping and looking around. The yacht was in commission. This was a great surprise. In Florida, if a boat is in running shape within two weeks of the promised time, the owner is rightfully entitled to boast himself a favorite of the gods. Rejoicing in such unusual dry-dock punctuality as a good omen, we turned our bow toward the southeast early the next morning.

A smart breeze whipped up the surface of the water into gay, dancing waves that sparkled beneath the bright sun and cloudless sky. The distant keys showed up fresh green, with an occasional white house snuggling close down to the water. On such a morning it was impossible not to be happy.

We tried to start a game of bridge on the after-deck, but the increasing strength of the wind rendered it very difficult to keep the cards on the table. Playing under such annoying conditions is no pleasure, so we gave the game up.

Dr. Meredith and Dr. Grame retired to a couple of deck chairs, and began one of those long discussions in medical terms which are intelligible only to the initiated. Mrs. Meredith evidently experienced a kind of call of the wild, and turned her energies to knitting socks for no one in particular. Nicky, who had been rather subdued lately, collected the scattered pack and made straight for the cabin, to dream over the architectural difficulties of constructing an extensive mansion of cards.

Eleanor and I wandered aimlessly forward, getting a pair of binoculars as we passed the cabin. Picking up the channel stakes was great fun for nearly an hour, until we plowed into the Gulf Stream. Then there were no more stakes to pick up and it was getting so rough that leaning over the rail to sweep the horizon with the glasses was extremely foolhardy.

We made our way back to the leeward side of the cabin, and stretched out in steamer chairs. We talked and gabbled away about everything and nothing as young people will, and passed the time enjoyably enough. The rolling of the boat was increasing perceptibly, and the wind contained a more strident note as it tore around the corner of the cabin.

When a grinning Japanese steward, in spotless white, came to announce that luncheon was awaiting us, I realized I was ravenous—and boasted of my desire to eat an elephant. But alas, the scriptures are only too literal when they state that pride goeth before a fall. Mine came with a vengeance. No sooner had I attacked my third piece of roast beef than I suddenly and acutely noticed the abominable rolling of the boat. Through the port-hole I could see the horizon mount swiftly toward the zenith, and then subside sickeningly. I stood it for several moments, and then was forced to take French leave.

The rough weather continued for four days while I endured agony. The fifth day was comparatively calm, and I convalesced on deck while we lay at anchor in the lee of a sheltering island. The Meredith family, with the exception of Nicky, were still confined to their beds.

In spite of myself I could not but feel gratified at this; for since I was the first to take to my bed, it was fitting that I should be the first back on deck. It had always been a theory with me that to succumb to seasickness was the rankest unmanliness. Although I now realized that I had formed my ideas without any basis of experience, still it was comforting to know that I had not been sick any longer than the rest. As for Nicky, he did not count. I believe his stomach was as leathery as his face.

Just before sunset one of the yacht’s launches appeared around a promontory of the island, and bobbed along toward us. As I stood and watched the boat, wondering where it had been and who was aboard it, the captain strolled up.

He was a big fellow with a strong square face, and hair tinged with gray above the temples; a man of some education and seemingly an efficient captain. Dr. Meredith had told me that he had had the captain for ten years or more, and held him to be indispensable. The only other thing I knew of him was that he was a great pal of Nicky’s. When the captain was not busy he spent a great deal of his time with the youngster constructing miniature ships and spinning strange yarns.

“They’ve been harpooning. Looks as though they’ve got something.”

“What did they go after?” I asked.

“Sawfish, porpoises, whip rays—anything big enough to attract a man eater.”

“Man eater?” I queried.

“Yes, man-eating sharks. We cut up whatever we grain, and the tide carries out the blood and oil. The sharks scent it, and it attracts them to the boat. Then we will show you some sport. How would you like to have a nice pair of shark jaws that you could pass right over your body without touching your sides?”

“Are their jaws really that large?”

I thought he was telling the truth, but you can never tell about those who have a touch of salt in their makeup.

“Certainly,” he replied earnestly. “They even come very much larger than that. If you cut out the jaws of a sixteen foot Leopard Shark, and open them, you will find that they will form a circle with a diameter of two feet or more; large enough to swallow a man whole, should the beast be inclined. However, they usually prefer to snap off a leg or two by way of getting up an appetite for their meal.”

“Playful little things,” I thought; then aloud, “And do you propose to rid the world of a few of these leopards to-night?”

“Yes, unless Dr. Meredith wants to move on to a quieter anchorage. I believe we are going to have more wind.”

At this I groaned.

“Even if we do move off,” went on the captain, “we can tow the porpoises, and the sharks will probably follow us.”

By this time the launch was within hailing distance.

“Get anything?” bellowed the captain.

One of the men in the boat held up three fingers and shouted, “Two saws and a porpoise.”

The captain turned to me and explained that when you get one “saw “you usually get its mate, especially at this time of the year.

“Does that apply to sharks also?” I asked.

“I really don’t know,” he answered, “but I don’t believe so.”

The captain and I moved to the stern in response to a call from the harpooners, and made their painter fast to a cleat.

“Shall we rip ’em, sir?” asked one of the sailors.

“Sure,” answered his officer, “and do it well, George.”

As George pulled the huge fish alongside the launch and began to work on them, I noticed he had a very likable face, deeply furrowed by the lines that a smile naturally brings to the features.

In a few minutes the “ripping “was accomplished, and the two sailors came on deck wiping their hands on their trousers.

“I’d hate to be swimming around here in a couple of hours,” remarked George as he went into the engine room to wash up.

The Merediths had not entirely recovered by dinner time, so the captain hauled anchor and set off for calmer waters. After a hearty meal, I went on deck to watch the scenery, and smoke. The wind had freshened a bit and was raising small waves on the surface of the water. The moon was shining brightly; small white clouds crossed its face now and then, casting dark shadows on the water.

Beyond the island, the wind was lashing the sea into white fury. I was very thankful that we were in a lee, as I watched the angry white-capped waves streaming out as though pursuing some unseen prey. As they came around the end of the island, they resembled a boiling mountain torrent as it lashes its way between the rocks and over falls. However, the water about us became quieter as we advanced. Leaning over the railing, I could plainly see the sawfish and porpoise we had harpooned in the afternoon, as they trailed through the water behind us at the end of a rope.

As I watched, there appeared a black shadow in the water and a darkish bulk came to the surface in a rush and flurry of water. There was a tremendous swirling on the surface and then a resounding snap. The form disappeared, taking half of the porpoise with it. Other dark forms were visible near the boat; they faded and grew strong again as the sharks took to deep water or approached the surface. I wondered how many there were, and tried to count the shadows. However, they shifted and faded so surreptitiously that I could come to no satisfactory conclusion.

Another one of the great beasts found the dead fish; there was another rush, swirl and snap. I shuddered as I saw the back ripped from one of the sawfish. Thinking how helpless one would be in the water with these tigers of the deep, I was seized with a great repugnance for my proximity to the rail. So I turned and sought a steamer chair nearer the center of the boat.

There were two figures moving about up forward; one a sailor, coiling ropes near the bow. The other looked to me like Nicky, but I could not be certain, as a black cloud had momentarily obscured the moon. He was wandering around with his hands in his pockets, evidently doing nothing.

I thought of the sharks again, and could not resist the impulse to take another look at them. So I made my way aft, and peered down into the water. However, no shadows were visible. Thus disappointed, I wandered back to the cabin and decided I would crawl up the stairs to the chart house to have a chat with the captain.

I did not feel like turning in and had to admit to myself that I felt my nerves—doubtless because of the sharks. Besides, I imagined that I would find the captain’s company quite interesting. However, the chart house was empty, except for the sailor at the wheel, who told me that the captain was below. I crawled back to the deck and went aft.