8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

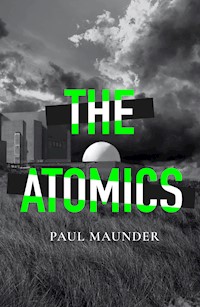

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A GOTHIC STORY OF MADNESS, REVENGE AND URANIUM-235 Midsummer, 1968. When Frank Banner and his wife Gail move to the Suffolk coast to work at a newly built nuclear power station, they are hoping to leave violence and pain behind them. Gail wants a baby but Frank is only concerned with spending time in the gleaming reactor core of the Seton One power station. Their new neighbours are also 'Atomics' – part of the power station community. But Frank takes a dislike to the boorish, predatory Maynard. And when the other man begins to pursue a young woman who works in the power station's medical centre, Frank decides to intervene. As the sun beats relentlessly upon this bleak landscape, his demons return. A vicious and merciless voice tells him he has an obligation to protect the young woman and Frank knows just how to do it. Radiation will make him stronger, radiation will turn him into a hero...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

OTHER BOOKS BY PAUL MAUNDER

Rainbows in the Mud: Inside the Intoxicating World of Cyclocross

The Wind at my Back: A Cycling Life

Published in 2021

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

ISBN: 9781785632327

Copyright © Paul Maunder 2021

Cover by Nell Wood

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

For Lesley

Contents

PART ONE

1 Uranium

2 Reactor

3 Containment

4 Neutron

5 Atom

6 Nucleus

7 Neutrino

8 Electron

9 Photon

PART TWO

10 Unstable Isotope

11 Decay

12 Alpha

13 Beta

14 Gamma

15 Half-life

16 Fission

17 Release

18 Chain Reaction

PART THREE

19 Energy

20 Heat

21 Pressure

22 Rotation

23 Electricity

24 Leaks

25 Waste

26 Contamination

27 Nausea

28 Fear

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PART ONE

1Uranium

Oxford, March 1968

Since the trial Frank had been on a leave of absence. Pending further psychological evaluation, the letter from the Authority said. So instead of driving the familiar route past wintry fields to the facility at Barton Hall, he went for a walk. Every day, shortly after Gail left for work, he swung on an old waxed jacket, filled his pockets with lemon sherbets, and set out into the sharp spring mornings. Their flat was at one end of a street which, at first glance, may have seemed respectable, lined as it was by Victorian villas and expansive trees whose roots ruptured the paving stones. Look again, however, and there was a mattress dumped in a front garden, a car on bricks, windows boarded up.

On this last day of March the sun sliced low over the chimneys. A soft wind carried the clang of barrels being unloaded at the pub on the corner. Frank thought of his street as representing a border, a transition between the nice roads to the north, where academics and wealthy students lived, and the not-so-nice roads to the south, crowded by workers from the Cowley car plants. Frank liked to be perverse, walking east along this imaginary borderline, as if reserving his loyalty. He had no allegiances. Not to town, not to gown. His line of work was cold and hard and unforgiving, like a steel blade. He saw the physical world around him – the brick walls, the parked cars, the overgrown front gardens – as bloated. Beneath the surface hummed the true layers of existence: the atoms and molecules too tiny for humans to crush.

This was his truth. His secret universe, invisible to all but a lucky few. Only a handful of men in the world did what Frank did. He was an expert in instability. His days, at least before all this nonsense, were spent bent over a microscope, examining radioactive material for signs of degradation.

And now… Now he just walked.

Past the little parade of shops. A decrepit old woman pushing a shopping trolley, a younger woman staring at her toddler. The mother as pale as a cadaver. Children did that to you. Beyond the shops was a metal gate, giving onto a small park – just a scrap of green hemmed in by ramshackle gardens. On its other side was an alleyway that led to the canal.

A very serious criminal incident…the letter had gone on to say. We need to ensure that you are wholly fit to return to work and do not pose a threat to yourself, your colleagues or the wider community. Was this to be another trial? Hadn’t the police done their job to everyone’s satisfaction? Would he have to become a monkey in the Authority’s laboratory just to get back to work? He missed his work. Away from it he was getting weaker, mentally and physically. Yes he’d been found guilty. There were too many witnesses to realistically expect any other outcome. But a suspended sentence meant he should be able to return to work immediately. He was a good man. He’d acted to protect the girl, in her interests.

When the letter came he composed a reply, informing the Authority that the only way they would get inside his head would be to split it open with an axe. Of course, Gail had opened and read the letter before he’d had a chance to post it, immediately ripping it to shreds. Idiot was the only word she’d said to him that evening.

As he neared the entrance to the alleyway, Frank noticed a couple on the other side of the grass, following the other path towards it. They were moving very slowly and seemed to be conversing quietly, their heads leaning together, though not in the manner of lovers. The man was dressed in a dark overcoat and had a rather comical shape – all shoulders and chest, teetering on tiny feet in dainty polished shoes. His companion was slight and walked with a stoop. She too had on a dark coat, beneath which a green dress swished around her knees. A black hat was pulled low over her eyes.

The pair separated, the man darting forward so that he reached the entrance to the alleyway ahead of Frank, who hesitated. But on seeing that the woman had stopped to light a cigarette, he carried on. They were having an argument, or perhaps the man was late for an appointment. Now they were between two fences, brambles and blackberry bushes narrowing the gravel path, their crunching footsteps falling into a rhythm. The man was ahead, his upper body swaying. Then Frank. Then the woman, for she followed him into the alleyway.

And just as Frank realised that the three of them were walking at the same speed, and wasn’t that a bit strange, the man stopped and turned around. Frank was about to say excuse me, but out came a pair of fists like mallets. One hand grabbed Frank’s lapel, the other jabbed him hard enough that he tottered backwards and wound up sitting on his backside.

The man’s coarse, florid face loomed over him, breathing cigarette fumes as he shoved Frank’s shoulders to the ground, then knelt on his ribs. His weight was crushing. The woman in the green dress stooped over them both. Now the smell of cigarettes was overcome with a sickly floral scent. Somewhere above them a crow began to laugh.

Her face was skeletal. White skin stretched over bone. Clownish make-up dragged across her lips and eyes. And those eyes… The fury in them made Frank’s body twist in fear. An icy burning sensation tore across his skin and his mind filled with noise as he made the connection. The woman in the magistrates’ court who’d shouted from the public gallery. Justice, this is not justice.

Her bruising accomplice backed off and she sank onto her haunches, her knees now on Frank’s chest, though she was no weight at all. And from her fingers flashed a short blade.

‘For my boy,’ she said. Her voice was hoarse and carried a country burr.

There was no pain as she pulled the knife across his face, starting at his temple and cutting diagonally, through an eyebrow, skimming his eyelid, deep into his cheek and down to the corner of his mouth, where she finished with a flick.

Heat spread across his skin, blood climbing out of his new fissure. Blackness. Swimming colours and sounds. A kick in the stomach that he barely felt because now came the pain screaming in.

2Reactor

When the ward was silent save for some low snoring from the old boy over by the window, when the stale hospital air began to choke him, when the painkillers began to wear off, he heard her footsteps echoing in the corridor. The nurses could not see anyone. They saw only their patient’s crazed eyes, not the lunatic who hunted him.

Pinned down by blankets, his face swaddled in gauze and bandages, Frank listened in rigid terror. She was coming for him. The cut had not satisfied her, she wanted to slash him again and again, to rip skin from bone. Some nights the footsteps went on for hours, rising and falling along the corridors, and dawn began to creep around the curtains before he could rest easy. Other nights the sound was fleeting, barely there, and he was able to drift into uneasy sleep.

Once, Frank’s eyes cracked open to find her standing over him. He cried out and swiped her arm away. A thermometer smashed on the floor and the nurse who’d been about to administer it jumped clear of his reach.

Other voices came swimming through the light, too.

‘We’ve got her,’ said a policeman.

‘My poor baby, ‘said Gail.

‘A pound of flesh,’ said his father.

When Gail first visited after his stitch-up session, they sat in silence, holding hands. She had on her beige mac with the big brown buttons, bright blue wool trousers, her hair pinned up. A heavy silence. A tear from his uncovered eye rolled onto the side of his nose and stopped there. Bandages absorbed tears from his wounded eye. Gail cried too, though like everything she did it was intense, demonstrative and quickly forgotten. A blow of the nose and a wave of the hand, and a thin bluster of humour took over.

‘What am I going to do with you?’ she said.

He said nothing. His lips were swollen, dry and cracked, and it felt like any movement might tear his stitches apart. A dull ache pulsed up and down the line of the cut. It was his eye, taped shut, that hurt the most. The doctors said his sight was never in danger because the knife had cut open his eye-lid and only scratched his eyeball, but he could tell from the look on their faces that they were worried about something.

That was two days ago. Two days in this bed, mummified, at the mercy of others. With that knife she had cut him in two. He was divided now. There would always be a scar to split left from right, past from present. His life now had two chapters: before her, after her.

Her name was Andrea. Devoted mother, knife-wielder, harpy. A mother of four from Didcot, the boy was her eldest. The police said they knew the family well.

‘Lou has asked if I want to go out tomorrow night,’ Gail said. Louise, her colleague from school, didn’t like Frank. He could tell by the way she looked at him. ‘You don’t mind do you? I’ll come here first for an hour, then get the bus into town. I’d only be sitting at home on my own.’

Though Gail often went out with her girlfriends, and she was right in saying that she’d otherwise be alone at home – visiting hours ended at eight, Frank felt somehow aggrieved. Something grated about her assumption that he wouldn’t object. Did she think she held more power over him now?

Yes, he was a prisoner, weakened by being opened up, but he would recover and rebuild. There was work to do.

• • •

In the snug bar of the Lamb and Flag, with a fire crackling in the hearth, honeyed light refracting through pints of beer and a good-natured hum of conversation, Gail felt the relief of escape. She and Lou sat close together on a bench, sipping their gins and looking out into the crowd of drinkers.

‘He keeps looking over, that one, yes, that one in the blue scarf,’ said Lou, who was, to use a word Gail’s mother liked, incorrigible.

‘Oh stop it,’ said Gail, shaking her head, but with a smile. ‘I feel bad enough for coming out.’

It was true though. The man by the bar did keep looking over, and it wasn’t Lou his eyes came back to. He was tall and slender, with an intensity in his face that she found attractive. Gail wasn’t interested in buffoons. Christ, that was her problem wasn’t it? Serious, intense men were exciting but, as she was finding out, unpredictable as hell.

Again, he looked over. Lou giggled and raised her glass to him. He quickly looked away, unable to cope with this level of communication.

Annoyed that her friend was still engaging in such acts of frivolity while Gail’s husband lay in the John Radcliffe Hospital, Gail said, ‘He’ll be scarred for life, they told me. Across his face, I mean.’

‘I bet he’s wishing he hadn’t got off so lightly at court. Wouldn’t have happened if he’d gone to prison.’

‘Lou…’ Gail said, frowning, though the same thought had occurred to her.

‘Would have made it easier for you to leave him too. If he’d gone down I mean. Now you’ll be playing nursemaid to Frankenstein.’

‘I’m not leaving him. He needs me.’

‘Gail, you know what he did to that boy. He will never be the same again. God, it’s a wonder his mother didn’t cut his throat rather than just his face. I’m telling you, you need to get out of that marriage. How do you know he won’t do it to you one day?’

‘I just know. He’s not a madman. He thought he was doing the right thing, protecting the girl. Remember that boy gave her a black eye. Frank got carried away, but he thought he was doing it to avenge her. He gets…he gets these ideas in his head, and it’s like he’s blind to everything else, and sometimes his way of looking at the world is so black and white, particularly when it comes to people, and…well, when it comes to people there are so many shades of grey. I don’t know, it’s hard to explain. But fundamentally he’s not a bad man.’

Lou opened her mouth as if to fire back a response, then closed it. Took a drink and stared off into the room. Gail knew what was going through her head. She was thinking that Gail sounded like every other wife who stood by an abusive husband. And Lou also knew how much Gail wanted a baby. Both women were thirty-two, and Lou had two daughters. She also had a successful and adorable husband, so could only justify infidelity by trying to stir it up for her friends.

When other men paid her attention, as they often did (though God knows why, she felt her youthful energy ebbing away every morning), Gail frequently played through a variation on the same thought process. About how life was essentially a narrowing of options, and a question of timing. She had been a few days shy of her thirtieth birthday when she met Frank and decided he had potential. Like a house standing alone on a hillside, unloved and with a dark past, he’d become her project. She loved his intelligence, his looks, his wry way of looking at the world. He didn’t drink and he didn’t lust after other women (or at least, if he did, he was very subtle about it). He was different. Though didn’t every woman say that about the man they fell for?

So different. Crazed, one witness had said in court. He wanted to beat the life out of that boy – that was plain as could be. If he hadn’t been pulled off, who knows? It could have been a murder charge… So many voices and opinions, but there were pieces of testimony that Gail couldn’t forget. Every day she’d gone to the magistrates’ court and sat hunched in her seat, feeling sick, ashamed of him, hating him for putting her in this position. Nothing she heard was really a surprise, not really. That he was capable of violence. That he had some misguided notion in his brain about looking after that miserable stringy girl who worked with him at the facility and started all this off by getting pregnant by a boy who was engaged to someone far prettier. He’d reacted to the news with a punch to her face, then Frank had decided to retaliate on her behalf. Not that he was in love with the girl – oh no, he was very clear on that (and Gail believed him).

Gail looked at the man in the blue scarf. Perhaps he was married, had children. Had that terrible affliction – the wandering eye. How many options did she have now? Leaving Frank was possible – it was – but not tonight.

• • •

Frank woke with an electric spasm. Confused, unable to establish where he was, he held himself very still and listened. There was the incessant tick of the clock on the wall opposite, someone grumbling in their sleep, a lone car on the ring road below. And closer, much closer, a new sound. Breathing, but not like any of the breathing sounds he’d grown accustomed to over the past two nights. This was a rasping, urgent and intense. And it was coming from the bed next to his, the one always surrounded by screens. He sensed, but could not see, movement. A body twisting under the pressure of sheer terror. Eyes that searched the ceiling in desperation, soon to be closed forever. Feet kicking uselessly, hands scrabbling at a noose that would not give. His mother’s body arching unnaturally in its final moments, her consciousness already exploding, her will to live long departed. Soon she would be free from her demons, and from her husband whose cruelty consisted mainly of refusing to acknowledge that she had any demons. And she would never see her son’s beautiful face sliced in two.

Frank inhaled sharply and the image, the sounds, vanished. The poor sod in the next bed went on softly snoring. The clock went on ticking.

He’d never tried to commit suicide, but he thought about it often enough. The method, the timing, the impact. Sometimes, standing on a tube platform, his toes began shuffling forward, involuntarily, without any conscious decision being made, and he had to tip his body backwards to force them back from the edge. He could anticipate the moment of breathless hanging in mid-air, the final blast of life before the thwack of the train and the bone-crunching down among the gravel and tracks and rat shit. A tidy way to go, really. The train companies were used to washing people’s brains off their advertisements. Some delays, a strong cup of tea for the driver, and everyone would get on with their day again.

But he would never kill himself. It was too weak, too feeble-minded. Just supposing he did, he knew he would surely make a better job of it than his mother had. After the third attempt he’d been so angry with her he told her precisely where she’d gone wrong each time. Not enough pills, learn to tie a decent noose, throw yourself off something higher. I’m indestructible, she smiled. And for a long time it had seemed she was, at least physically. It wasn’t long after that Dad moved her into Parkview, a bland name for a place of such anguish.

There she had cleverly managed to asphyxiate herself by tying her dressing gown belt into a noose, securing the other end to the bed frame, then sliding out of bed. Finally, after all those amateurish attempts, she became expert at suicide.

3Containment

Three months later

Bloody thing. Why won’t it move?

Cigarette clamped between his lips, one hand on the steering wheel, Frank tugged at the window handle, trying to gauge how hard he could pull before it came off. A quarter-turn then it stopped. He glanced back at the road, wriggled in his seat and tried again with more force. Bloody thing.

A quick acidic reaction coursed through his chest. He banged the wheel with the palm of his hand. The anxiety that had been twisting through him all morning, souring the whole journey, now fused into something stronger, a more satisfying anger.

He looked across at Gail. Fed up with talking to him she’d put her seat back and gone to sleep even before they’d got clear of Oxford. She was hungover of course. While he’d finished the packing and cleaned the flat, she’d gone out for a ‘quick goodbye drink’ with her girlfriends, eventually stumbling in at ten to one. By the time she’d managed to haul herself out of bed he had the car packed and everything else sitting in the hallway for the removal men, who, apparently taking their cue from his wife, turned up forty-five minutes late. Drinking cups of tea and chain-smoking, she sat at the kitchen table in her dressing gown while he stripped their bed, picked up her dress from the bedroom floor and supervised the loading of the van. As soon as they left it began to rain.

In the newly-freshened light her skin looked marbled, the daubs of make-up crude and plasticky. Her mouth was agape, strands of blonde hair stuck along her jaw. He followed the collar of her dress down to where her breasts pulled the printed cotton taut, creating little gaps to peer through, then down over the bulge of her tummy. It was one of her favourite dresses – she’d laid it out yesterday afternoon, with matching shoes. The tender white of her thighs was visible where the dress split, wobbling a little when the car bounced over a pothole. Frank put a hand to his crotch. And as he hardened, so, obscurely, did his anger. He drove faster, eyes flicking between the road and his wife’s body. Sweat pricked at his temples until a single bead trickled towards the corner of his eye. He needed some air. The bloody car was too hot. Gail gave a little snort and rolled her head away from him. Frank reached down to the window handle and wrenched it so hard it snapped off in his hand.

• • •

The land was broad and low. Featureless, save for the church steeples that pricked the streaked sky at regular intervals. At school he’d been a decent cross-country runner. His favourite event, the biggest of the autumn calendar, was a steeplechase starting and finishing in the Somerset village where he lived, looping out across the Levels to take in three other villages. The memory was still vivid. Splashing and leaping along the edges of waterlogged fields, lungs rasping, fingers numb, looking up for the next bobbing steeple, knowing there would be a crowd in the village to cheer the runners on.

Now he was going to reclaim the sense of space, of a limitless horizon, that he’d possessed at ten years old. Of Setonisle, their new home, he had only a few blurred images in his mind – he’d only visited once before agreeing to the job and hadn’t been allowed to take pictures. The man from the Authority had painted it as an incredible opportunity for his career, for his reputation, but he wasn’t fooled. They just wanted him away from Barton Hall, away from the scene of the crime. The boy’s mother, Andrea, had gone to prison and her friends were deluging the facility chief with threatening letters. So Frank was to be redeployed to the Seton One power station, so far east that it was practically in Finland. No interview, no psychological evaluation (despite what their letter had said), no choice. They just made it happen. The day of his visit, in May, had been unseasonably cold. The wind blasted off the dark North Sea waves and excoriated him as he stood in the middle of a labyrinth of metal and concrete.

Frank lit another cigarette, rolled the car around a lumbering tractor. Over the summit of a low hill he could see fields stretching ahead, a giant jigsaw puzzle. A pair of larks sketched arcs against the cornflower sky. For the first time that morning he felt free of Oxford. He hadn’t realised just how much the city bore down on his shoulders. Out here he was able to breathe, to ease the perpetual frown that, he knew, put strangers on edge. Looking across at Gail he felt a sudden nagging sense of gratitude that she would follow him out here, that she would give up her own job, her friends, her nights out in the West End. Their new life would be very different.

‘Where are we?’ she said, twisting forward in her seat and squinting against the sunshine.

‘Not sure really,’ he lied brightly, for he knew they were on the A14, 77 miles from their destination. ‘Somewhere in deepest darkest Suffolk.’

‘What happened to the rain?’

‘It stopped.’

‘More scientific magic, huh?’

She had once asked him what electricity is. After he explained the basics, clearly and concisely, she’d repeated the question. Yes, but what is it? I can’t see it, I can’t touch it, I can’t smell or taste it. So how do I know it exists?

Gail lived a sensual life. For her, the world was immediate and raw. She reacted to what she could see in front of her and ignored the abstract, the ethereal. It wasn’t that she was stupid; just that all her intelligence flowed through her emotions. Other people’s problems weighed on her, and other people’s joy buzzed through her. In company, her sensitivity to others made Frank ashamed of his own coldness. If he ever said as much to her, she told him he needed his detachedness, it was part of him, part of what enabled his work. He had no explanation for what attracted her to him other than that hackneyed maxim; opposites attract.

She turned to gaze out over the land. Originally a Londoner, she saw only blankness when she looked at a place like this.

‘Beautiful,’ she said. ‘A fresh start eh? An adventure.’