Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Wrecking Ball Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

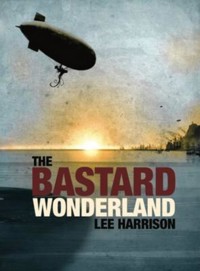

In a land not too far away and a time yet to be decided, one man and his Dad embark on an epic journey of war, peace, love, religion, magnificent flying machines and mushy peas. The Bastard Wonderland is the astonishing debut fantasy novel from Hull writer Lee Harrison.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 567

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BASTARD WONDERLAND

THE BASTARD

WONDERLAND

Lee Harrison

THE BASTARD WONDERLAND

Lee Harrison

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN 9781903110454

First published in this edition 2016 by Wrecking Ball Press.

Copyright Lee Harrison

Cover design by Lee Harrison and Owen Benwell

Typeset by leeds-ebooks.co.uk

All rights reserved.

Part One

At journey’s end, we look awed upon an endless coastline of silver, seeming both temperate and fair. The solitary, stooping mountain stands there as an emissary, respectful to the lands we have left behind, yet welcoming to a world of undiscovered wonderment.

— 1624 entry from the Journal of Captain Olaf Hagen, the founder of Aaland.

1

SCRAPING THE BARREL

The Call of March bucked the waves, groaning against her anchor lines as she waited for port. Sun beams spilled through the rigging, etching a broken-nosed scowl across Mr. Warboys’ face as he smoked sullenly against the gunwale.

He squinted at the churning city port that was supposed to be home. Coperny sprawled across the visible coast and half way up the mountain, the smog of newfound industry greasing the sunlight over the bay. The bow-backed shape of a half built viaduct loomed over the upper town, launching a glittering tramway over the city. Up through the haze, he could just about make out the weathered statue of Hagen the Founder on the summit of the mountain, crowned in flocks of shrieking gulls, his shit-striped arms open in welcome to the world’s newest nation. The clamour of folk hit Warboys’ ear intermittently through the roar of the wind, and away through the mesh of harboured masts he could see crowds gathering on the wharves, the facades of otherwise grim dock offices draped in arcs of red and black bunting.

A mob of deckhands gathered on the foredeck beyond Warboys, loafing with their smokes, jumpy with the anticipation of pay and shore leave, and made still giddier by the sight of the celebrations.

‘Must be our welcoming party,’ cackled one, scratching his scalp beneath a frayed woollen cap.

There was a collective laugh, but Warboys spat into oily, rainbow coloured waves, and did not crack a smile. They were getting on his nerves.

Through the ragged aisle made from awaiting vessels, a trade schooner – the Katerina, out of Nyssa – emerged at half sail. The deckhands leaned outward like wallflowers, eager to gather news.

‘You’re in for a right treat here, my lads!’ grinned the Katerina’s mate, hanging from the rigging nets as she cut through the surf. ‘King John’s fucking abdicated! Stepped down he has, and gone off with his Jurman poofter! General Malvy’s already sworn himself in and abolished the throne! We’re a Nation State, now, he says!’

‘Fuck off!’ scoffed Warboys.

‘Ha! Not a word of a lie, mate! And that ain’t all. He’s marching on Blackhaven! He’s on about uniting the whole continent, Andamark, the Blacklands and all of it, right down to the fucking peninsula and across the islands! We’re rousing for war, lads!’

He laughed as if this were a right scream.

‘Give over! Blackhaven?’

‘It’s true! He’s going to announce it now, in person. Why do you think you’ve been waiting so long for port? They’re drafting every cross-eyed fucker they can catch! You’d better have your papers, lads, that’s all I can say. Prove you’re worth your salt, like!’

And off he went, laughing as the Katerina’s bow wave hit the Call, dipping Warboys’ stomach. The deckhands exchanged nervous glances.

‘What we invading the Blacklands for?’ whined one. ‘There’s knack all down there but sheep and savages.’

‘Say what you like about King John,’ said a varnished veteran, ‘he saw the sense in leaving the backward bastards to their swamps and bogs. Seems like Old Jonah don’t see fit to honour the agreement.’

Shit, thought Warboys. The speculation began, and he wasn’t much further on with his analysis of the situation when Jacky Biel, a gangly beanpole of a deckhand, appeared beside him.

‘What do you reckon then, Warboys?’

Warboys squinted at Biel as if he were a stripe of seagull shit. Biel’s mates sniggered and nudged one another in anticipation of fun.

‘I bet you wish you’d finished that chartership, eh? Your old man can’t help you now!’

‘Piss off, Biel,’ snapped Warboys. Privately, he felt a stab of anxiety at the mention of those two things – his chartership, and his dad. Like most work, the chartership had seemed like a waste of effort at the time. Now he didn’t have the papers to entitle him to a berth as a seaman, he knew he was out of a job again. And the old man would be there outside the Dock Offices, waiting for him. Ready with an earful, like he always was when things went wrong.

‘I’ve always thought you was the infantry sort,’ said Biel. ‘Here, you’re a dab hand at taty peelin’ aint you? An army marches on its taters!’

They laughed again, and Biel’s pungent smoke smelled of his smugness. Warboys fumed privately, but shrugged.

‘The infantry ain’t so bad.’

‘Yah, if you survive it’s alright. Malvy won’t last. He’s a fucking lunatic. They’ll find some new bastard for a king, and the sea’ll still be there and it’ll still want traversin’.’

‘You might be ‘appy comin’ and goin’ from this dump for the rest of your life, but I aren’t. I still want to go somewhere. I want to see summat different. Make summat for myself.’

‘Ah well,’ shrieked deckhand Ives from among the mob. He was a young, pasty faced accomplice to Jacky Biel, and a gobshite to boot. ‘You can make yourself some nice roasties once you get back among them taters!’

Warboys fixed Ives with a warning glare which the young lad was too giddy to pay heed to.

‘It can be hard work though, taty farming. Musn’t let it get on top of you…’

‘Yeah,’ added Biel. ‘Ask Warboys’ old lady!’

The laughter was uneasy this time. Warboys stiffened and straightened up, pointing his smoke at the two of them.

‘Smile whilst you’ve got the teeth for it, you gangly fucker. We’ll be off this tub soon, and I’ll be seeing you.’

‘Oh look, now Warboys mate, he didn’t mean—’

‘I know what he fucking meant.’

‘Flag!’ came a yell from above. ‘We’ve got the blue!’

They scattered keenly, and were rousing to make port before the first mate could bark orders. Soon the Call was easing into the inner harbour, through boulevards of bare masts. The crew jeered as a tin-pot steamer waddled by, belching out clouds of white smoke to briefly swallow the scenery. More news and rumours were exchanged from ship to ship, but Warboys didn’t listen.

He hauled rigging, feeling a gloom in his stomach. In this harbour he’d sat idly on jetties, smoked when he was too young to smoke, boasted of all the places he could go, the money he could earn, the women he could have. Yet here he still was. A nobody hard over the wrong side of thirty, still to-ing and froing to neighbouring ports on chance commissions. Still bearing earache from his old man, even as revolution seemed to have arrived, and still the city toiled on, indifferent to him.

The Call came to dock, pulled instantly into the rabble as mobs of angry merchants and dock officials descended upon it, bawling at the captain with their quarantine regulations, contracts and hassle.

~ ~ ~

A checkpoint choked the wharves, packing alighting sailors together like livestock. Moustached conscription officers manned the gates in heavy greatcoats, calling for papers, herding men through a course of tents and holding pens. Glowering propaganda plastered every surface, promising the world for a bit of graft. Warboys had grown up with tales of the last war, in which General Jonas Malvy had made his name as the bulwark of Aaland. Old Jonah, that grounded, salt-of-theearth figure at the throne’s side. Now though, when it seemed the coup had won him the country, Warboys felt Malvy’s poster-painted face glaring at him from every surface, and didn’t feel so reassured. NO LONGER SHALL AALAND OBEY THE PAST, claimed one poster, picturing a great fist toppling a white castle. SEIZE THE FUTURE! The violent reds and blacks set the men as nervous as sheep.

Warboys craned to see that the line was being split into two. To the right went those with chartership papers, off towards Dock Street and freedom; to the left went the others, off to sign their lives away whether they liked it or not.

‘That’s you sorted then, Warboys,’ sniggered Jacky Biel, his beany frame edging out of the mash of bodies. ‘Least somebody wants you, eh?’

Warboys bristled at Biel’s buzzardlike profile, but held himself, watching what happened at the gate. Before them, a ginger-haired deckhand named Calvert shifted anxiously, trying to slip through the gate unchecked. Without even looking, the officer slapped his hand on the lad and stopped him dead.

‘Have you got your papers there, my lad?’ asked the officer, puffing up so that the buttons on his greatcoat bulged like eyeballs.

‘No sir.’

‘Might you, then, be interested in a career in the forces?’

‘No sir.’

‘But you’ve got no papers? Might I remind you of the Public Responsibility Act of 1864?’

‘I ain’t ’eard of it, Sir.’

‘Well, allow me. Passed days ago it was. It says that if you come through port without meanful gains, son, that’s a criminal offence. And in these days of great need, it ain’t practical to keep a grown man in a cell. We’d have to conscribe him into national service, like. Pay his dues. So I asks again, sir. Have you ever considered a career in the forces?’

‘I ain’t no fighting man, sir.’

‘Listen lad. Our good General Malvy is scraping the barrel here. Every last man, barrel and duck is to be used. This country ain’t no respite. It’s a well oiled machine.’ He leaned to growl in the boy’s ear, pointing at the red and black Malvys as he did. ‘If the duck can’t fight, it wants to be shot and ate.’

With that, the officer collared the poor sap and shoved him off to the left.

‘Ho ho!’ bellowed Biel, nudging Ives. ‘Not so cocky now, is he? I reckon we’ll be parting ways for a time here!’

Warboys considered. Part of him would rather be drafted, rather than have to explain himself to his dad. But fear blossomed once again as he saw Calvert make another weak run for it, knocking off the officer’s hat. Biel and Ives guffawed again, heartily enjoying themselves.

Warboys saw his moment.

‘Listen,’ he began amiably, giving Biel a pally nudge, ‘Jack, mate…’

Biel’s big nose had barely turned before Warboys stuck the nut on him and mashed it across his face. Biel sagged where he stood, fingers relinquishing his papers as he fell into Ives, and Ives tumbled into the man behind him, causing a ruckus among the tightly packed sailors. Warboys backed off toward the gate, hands raised in a show of innocence. Ives managed to scramble from the brawl to catch Warboys with a jab, just as the officer – fresh from seeing Calvert off – turned back to his post. Warboys padded his eye, resisting the urge to fight back, holding Biel’s chartership papers up and trying to pull as lovely a face as he could. The officer moved to set about Ives with his steel tipped Jonah, but then Jacky Biel squirmed his way from the cranked arm of a moustached man, squeaking ‘He’s nicked me papers! Check him! His name is Warboys, not Biel! I’m Biel! Check him!’

‘Hang about, mate,’ grunted the officer, beckoning to Warboys.

‘Piss off!’ yelled Warboys, indignantly, pointing at Biel. ‘He’s Warboys! He didn’t even finish his bloody chartership! He’s got his name tattooed on his arse, look, case he forgets it.’

When the officer turned to see if this were true, Warboys ran.

Through the gate, he skittered over cobbles sparkling with oil and fish scales, and careered towards where the grand turrets of the dock offices loomed over the street. A line of deckhands curled out from the office like dirty dominos, waiting to claim their wages. All around them, women, children and old men crowded the street, doting on loved ones fresh through port. Some wore red flags or shawls, joining the spirit of General Malvy’s declaration.

Then, amongst this merry throng, Warboys saw his dad.

William Warboys senior – Bill to those in the know – was a moustached man as thickset as Warboys, but with a more wiry, greyer head of hair. He stood frowning in his old charcoal jacket, puffing away on a paper smoke like a relic seeing out the last of the old days.

Bill’s frown deepened, his smoke pivoting on his lip as he saw Warboys hurtling towards him. ‘Now then!’ he exclaimed, then, ‘Oi!’ as Warboys promptly hurtled past. Warboys said nothing, lest the officers collar his dad, but managed a constipated look that he hoped might express some kind of apology. He sailed by, letting Dock Street sweep him along, around carriages and guard troupes, past dockers shuffling from fish and dry docks. At the next junction, the muffled sound of a brass band pulsed unevenly from up the street. Armed infantry choked the road at a check-point, and Warboys slowed, seeing the crowd ahead arise in density until he could see nothing but people: soldiers, flat caps, glosswaxed ladies, all the masses assembling to hear the great General speak from Junction Monument.

Warboys turned to see the officer – now with a few burly grippers in tow – edging against the crowd to scan for him. He ploughed on, through deckhands spilling from Dock Street Tavern in rowdy, smoky groups.

A carriage clattered around the corner, earning a dull cheer from onlookers as it veered to avoid him, spilling mud-caked yams across the cobbles. One of the grippers chasing him had just enough time to point and exclaim ‘Oi!’ before the crowd closed in, opportune hands stuffing yams into pockets, blocking Warboys from view.

He fled into the vomit-spattered alley by the tavern, stumbling through overflowing bins. The alley bent sharply, and Warboys almost piled into a sailor having a topless handshandy with his sweetheart.

‘Don’t mind me,’ he grunted, edging past. ‘I ain’t here.’

‘Me neither, love,’ croaked the sweetheart.

The alley ended at a boarding that glared with more propaganda. Warboys paused a moment, to see if he had been tailed, but could only see the sweetheart, her forearm beating away energetically, at odds with her stony face.

The boarding bent nicely, allowing him onto an alley partly obscured by a row of half-demolished buildings. Warboys picked his footing carefully, looking for some refuge among the gutted buildings. Sparks of light winked through gaps in the boards facing Dock Street, where the racket of the waiting crowds rattled through. Men coughed and blustered at one another over the sound of the band. A woman shrieked. A child nattered for a peg up.

There was a creak behind as someone shoved through the boarding. Warboys ducked into a doorway, expecting the grippers to come piling through after him. Then his dad arose, muttering curses.

‘Bloody idiot! What are you…’ was all Bill could manage before doubling over in a fit of coughing.

‘Bugger off!’ hissed Warboys, hoping to god the old sod wouldn’t start ranting at him here. ‘You’ll get me caught!’

But Bill staggered obliviously toward him, cursing as he joined Warboys in the doorway.

‘They’ve gone,’ gasped Bill. ‘Too busy today to bother for long with the likes of you.’ Even as he said this, Warboys caught a fleeting glint of pride in Bill’s eye – a look that always surprised him – and made his stomach tighten.

‘How did you find me?’

‘You ran down here that time the captain quarantined you for being pissed at the tiller. What have you done this time?’

‘Dad, I haven’t—’

Just then, the brass band faded into flatulent tones, and a hush fell over Dock Street. Bill nudged Warboys to shut him up. Then an officer could be heard yelling the order for quiet, and the two Warboys stalked toward the boarded windows. Quietly, they scaled a cracked staircase to crouch at a window overlooking the street, and settled there. Warboys sensed a reprieve, knowing his ticking off would have to wait whilst they heard what the Great General Malvy had to say for himself.

2

THE END OF HISTORY

Warboys had not seen so many gathered since the day Bill had brought him to see the first steam tram unveiled. A sea of humanity blocked the streets from Dock Street to Junction Monument, and from there all the way down to Nethergate. At the monument itself, flanking a lectern in the centre, the admiralty of the navy lined up on a raised stage opposite the generals of the army. Among a quietly apprehensive public, the posters that patterned the walls – AALAND UNITED! – seemed like the loudest voices. ASK NOT WHAT AALAND DOES FOR GOD, proclaimed the slogans, BUT WHAT GOD DOES FOR AALAND! Up on the peak, the statue of the founder could be seen, his arms raised in frozen apprehension.

With neither fanfare nor announcement, General Jonas Malvy climbed up to the stage and took the lectern. There was a general creaking of boots as everyone stood up on tip-toes to see this great figurehead. He’s actually quite a little man, thought Warboys.

‘Citizens of Aaland!’ the General cried out, the amphitheatre curve of the monument’s face making his voice resonate with surprising efficacy. ‘I welcome, and salute you on this portentous day.’

The General took a moment to survey the gathering, as if he were doing a private roll call.

‘This day marks the end of history. And so I present to you… its obituary.’ Warboys here noted that Bill had begun tutting and muttering in disapproval almost as soon as Malvy had taken a breath. With practised effort, he tried to block the old man out so he could listen.

‘Our history began when the great explorer Hagen crossed the western ocean to discover and claim this land for the Empress of Old Cory. He named it Aaland – the New World. Hagen saw the endless possibility, the great freedom to be found in what he called the land of wonderment. But the other great seafaring nations of the West followed – those who had long since colonised the Arricas and the Asiat, then squabbled in the southern seas like angry ducks ever since. And so came two hundred years of dispute, culminating in the Andwyke War, when the Empress bludgeoned a way to victory with an unprecendented display of naval might and heartless cruelty. Her son, King John the Tenth, was placed here as her Regent.

‘I fought in that war, my friends. Like many of you, I fought to put John on that throne. Did we feel pride, my friends? Did we feel that the blood shed over the years had brought us to a glorious peace?

‘No! We were rewarded with betrayal! And I was guilty, my friends. I stood by and saw Hagen’s land of wonder treated as little more than a slave colony! Watched John Ten let our men struggle and die to cement the power of the West! Watched John Ten let our children starve and suffer to line the pockets of aristocrats in distant Imperial courts! We did not fight for independence, but for their monopoly! John was not a king, but a common fence for his old lady! A clothes prop! A chicken placed on a plinth ready for plucking!’

Here Malvy made a neck-wringing gesture, his rage giving way to savage humour. He allowed a pause to let the crowd laugh. Warboys smirked despite himself.

‘My friends, on seeing this great land abused, I realised how weak monarchy is. How decadent. And so I saw fit to remove it. Remove the hold the history of the west has had on us all. I declare now, that King John is no more. The old Empire no longer has a claim on us.’

There was a reserved cheer then, a conservative round of applause as Warboys sensed the same uncertainty he himself felt – is this a good thing? He stole a glance at Bill, but the old man remained stony faced.

Malvy raised his hand to speak again.

‘With the monarchy, so history dies. We are not our history. Our time has come. We are not defined by the old nations. We no longer carry their rule, nor their religion. We cast off the shackles of the past, and we become what we will. Aaland will be first to claim the future.’

Another, more rigorous round of applause.

‘But… The scar of the Andwyke War is still fresh. Though our brothers in Andamark, to the north, are now our allies, the south is still lost to history.

‘The south was too difficult for the monarchy. Full of savages, they said. And thus, always more concerned with profit than national pride, John Ten left a convenient place to let rebels, and the defeated dregs of colonial forces flee, and there regroup. With this negligence, history keeps a creeping hand on us.

‘Even now, Blackhaven, once a fine port, and our furthest great outpost in the south, is threatened by uprising. There, rebels seek to make a hostile frontier. To divide the Andwyke once again. They would threaten to pull Aaland into another power play between her own people, and so another Andwyke War. And I say no! Never again! Unity is the way.

‘Already we lead the world in industry. Within six months, this viaduct will complete the great north south tramway, from Becohore in the north, down to the peninisula, and make Coperny the axis of the whole continent!’

Here Malvy pointed skyward.

‘And if you still doubt, my friends, look up.’

There was a murmur among the crowds as all faces raised. Murmurs became gasps and exclamations. A woman squeaked as a great shadow spilled over the tops of the buildings and over the crowd. Warboys craned and saw the tail flukes of some great oval flying thing disappear over the roof. There was not a sound as several more loomed, great ships of the sky, with airscrews flickering in the sunlight. Airmen waved from the gondolas rigged beneath, showering the streets with fluttering handbills. Warboys caught the rising fever of the crowd as he stepped from one side of the stage to the other, watching the great air balloons wheel about overhead.

‘As Old Cory were first to the seas,’ cried Malvy, with triumphant glee, ‘we are first to claim the skies! Soon our Eyrie – the world’s first Air Station – will straddle the mountain. We are the world’s first and only air power.

‘The so-called Blacklands, the Wyvern peninsula and the many islands beyond, all these lay in waste because of the decadence of the royalty. We will reclaim Blackhaven, and the rebels – as any who oppose our freedom – will be swept away by the inevitable advance of progress. We will soar across the Wyvern, and unite those far flung islands! There will be no Andwyke War, but Andwyke United!

‘I give you the chance – a chance of Public Responsibility that has never existed in history – for you to claim the fruits of your own labours. I bring you the chance at equality. Modern man is a soldier, no longer a slave. Aaland will lead a united Andwyke, and we will be freed, once and for all!’

Malvy hesitated, as if overcome with emotion. ‘I thank you, my brothers, sisters, my comrades… I commend you.’

He stepped down. There was stunned silence. Warboys, not sure what he made of it, waited with bated breath for the public reaction. A thunderous applause erupted as the crowd seemed to take to Malvy’s words.

‘Yah!’ objected Bill, a moment later. ‘What’s he on about? He’s a fucking lunatic!’

And with that, he patted for his tobacco pouch and made for the stairs. ‘Come on. We can nip off in the crowds.’

Warboys followed hesitantly, but as the cheering thundered on, he found couldn’t be as dismissive. There in that applause, that shift of volume, he sensed that somehow, in some way he couldn’t yet fathom, everything had changed.

~ ~ ~

It was a long time before they could speak freely. They forced a door further along the row, and barged out to join the dispersing crowds. An honour guard of glaring posters watched the people from walls and shop fronts, whilst volunteers lined the streets, handing out Malvy’s little red handbook – the Dictates. Bill took one for appearance’s sake, then dropped it once they were out of sight. A checkpoint had been raised at the end of the street, armed soldiers yelling to divert them along a prescribed route.

‘I’m not going that bloody way!’ moaned Bill. ‘We’ll have to march all the way out round bloody Rye Hill to get to Kingstown!’

He didn’t raise this objection with the armed soldiers, and the two kept their heads down as they shuffled past. Soon they crossed a canal and left the city centre, passing lumber and dock yards, until the crooked chimney pots of the Kingstown district arose, forming faint battlements in the haze. The crowds thinned as folk turned off down this terrace or that, hurried along as dark clouds drawing in from the west began to spit. Abandoned flyers lay plastered across the cobbles and Warboys sighed, feeing the old familiarity of home usher away the grandeur of Malvy’s rally. One last pair of soldiers watched them from horseback as they crossed a swing bridge into Kingstown and, finally, they walked unwatched, their pace easing some.

‘I never did owt wrong, before you start,’ began Warboys, deciding to get it over with.

‘You ain’t been fightin, then? I suppose that’s girl’s make-up round your eye then, is it?’

Warboys touched his swollen eye guiltily, recalling Ives’ lucky jab.

‘I told you, if I had to sail with that Jacky Biel, I’d be forced to deck him. Coming out with all the taty jokes about the old lady all the time. Gobshite, he is.’

‘You got to be careful now, son! It ain’t as if I never had a scrap in my time, but things is different! It’s Malvy’s world now! Have you thought about how you’re going to get back on board, now? When do you sail again?’

‘Listen. They already let me go. They’re only taking on chartered seamen now.’

Bill was silent. Warboys fished in his pocket, found a packet of tobacco he’d saved, and passed it over. ‘Here, I got you some blackleaf from Junkers…’

‘You trying to sap me, boy?’

‘Aye, maybe a bit…’ Warboys cringed, ready for a lambasting. But fingering at his new blackleaf seemed to go some way to mellowing the old man, and he halted by a lamp post to roll a smoke, eventually exhaling disappointment in a silky plume.

‘Don’t suppose I’m surprised. This country’s being whipped out from under our fucking feet. Homes, jobs, the lot. Reallocation, they call it.’

Warboys said nothing, happy to ride his luck.

‘To be honest son, you’re mebbe best out of it. In my years at sea I never seen such a shower of shite as what they’re stackin’ in boats these days. Some o’ these bairns are no good for scrapin’ dung off the King’s road, nivver mind sailin.’

‘Right. Thanks.’

‘No, never you mind son. You carry on—’ Warboys rolled his eyes, mouthing the old man’s tired old phrase along with him. ‘You look forward, and summat’ll always turn up.’

Bill slapped his back. ‘I’ll get you sorted for summat, son.’

‘Aye,’ sighed Warboys.

Bill scratched his head. Warboys yawned, and tried to think of something to say. A haggard tomcat slotted slyly behind some bins and along the wall into shadow.

‘Here, Cait Garron’s been asking after you,’ said Bill, eventually.

‘Has she?’

‘Aye. She’s got a bit of a bump in the front of her an’ all.’

‘Oh aye?’ Warboys managed to shrug innocently through Bill’s scrutiny. ‘What did she want?’

‘She never said. Knew you were due home, though.’

‘Oh well…’

‘Hadn’t you better go see her?’

‘There’s time yet.’

Bill waited, as if for some confession, and Warboys smoked through another awkward silence. ‘Here, how’s your allotment?’

‘Not bad son. Keeps me fit. I’ve been expecting the bastards to take that an’all…’

‘Aye?’

‘Aye.’

‘No stories to tell then?’

‘Nah.’

The old man shrugged. ‘Aye, well. Like I say. There ain’t no more stories to be told.’

Rain sapped conversation as they trudged on through Kingstown. They crossed the swing bridge over the muddy river Jet, and Warboys glowered at the rows of terraces.

‘Hang about,’ said Bill, casting away the dog end of his smoke to nip off down a side alley. ‘I need a piss.’

Warboys rolled his eyes. Why does he always have to announce it?

The rain hammered on. It made an orb of luminous spikes about a lamp-post overhead, and a struggling drain gurgled below. Warboys looked out over shimmering cobbles into the rain. Dim lights winked cosily from cramped houses, and he felt a bitter kind of nostalgia.

He remembered being outside the Blackwater Tavern, back when his mother had been alive, and Bill was home from sea, waiting outside with his mates, eating a patty butty whilst they had a kneesup. Nana Warboys’ house was just across the road from here, beyond the tenement arch, and round the corner was the passage where he’d first copped a feel of Caitlin Garron. Over on the muddy green he’d scrapped for respect, and over on the corner was where he and Sykesy had ambushed the baker’s boy and brayed him for his pies and pamphlets. Then, once he was old enough to drink himself shitfaced inside the Blackwater, came all the graft and queueing and misery. Now, revolution or not, he still faced the same lack of prospects, and felt a sense of hatred for all the potato fields, greasy factories, timber yards and mines he’d already done the rounds of over the years. Perhaps he should have let the draft get him.

Warboys’ smoke dwindled.

Something bashed him about the back of the head.

He skidded on the cobbles and stumbled forward, then spun on his knees, expecting muggers, grippers maybe, perhaps Jacky Biel and his mates. He got ready with a punch in the nuts for starters. But there was only the empty street tittering with rain.

‘Dad, did you…’

A clinking sound spun his attention toward the bridge, and he spotted something thin, jigging down the road towards town. It took a moment to recognise it as a rope, a rig of sorts, and trailing a curiously small anchor. He followed the line upward, just as a shadow yawned over him, a huge, oval shape that split the rain momentarily. He watched odd flukes flap from its whale-like form, until the rain tapped him awake again.

An airship.

He stared in disbelief as it swung away toward the bridge, entirely unmanned, loose rigs trailing alluringly along the cobbles like a tart’s knickers.

Warboys turned, opened his mouth to shout again for Bill, but then felt suddenly loathe to let it go. He set off, stiffly at first, but as he broke into a run, a great foolish grin broke onto his face.

3

UNDISCOVERED WONDERMENT

Warboys caught hold of the anchor line and felt the ship dip for a few yards before hauling him up. His legs flailed in the air, as his weight tilted the ship to starboard, bringing it about in a wide circle over the street. Beneath the sound of the rain on the balloon, he heard Bill’s voice.

‘Where are you, y’ bloody lummox?’

Bill trudged out as the ship’s shadow slid over him.

‘Alright Dad!’

‘Here!’ gasped Bill, sidestepping in pursuit. ‘What… what are you doing?’

‘What does it look like I’m doing? I’m off! To the land of undiscovered wonderment, and beyond! Ha!’

‘Y’ soft sod! You’ll kill yourself! Get down here!’

Warboys laughed and the ship came about, heading for the river. Bill managed to catch another stray line, and sank on his heels to anchor the craft, steadying it enough for Warboys to scale the rope and haul himself over the gunwale.

‘Here!’ objected Bill – but, as Warboys flopped on board, he was too mesmerised to hear the old man’s remonstrations. A cracked lamp swung over a deck somewhat like a small boat, probably less than twenty feet from prow to stern. The next thing he noticed was the stink. A warm, flatulent odour steamed up from the deck, and from a riveted stove-like thing in the midship. From the lid of this came a segmented pipe that fed directly into the balloon. A small raised deck sat astern, upon which lay a hooded array of controls. Compasses, gauges and meters blossomed from grimy pipes, their needles twitching inanely. A fine, pegged wheel had been installed, alongside various levers and pulleys that he did not understand. Various hatches patterned the deck. Other than a faint whooshing from the airscrews, there was no engine sound, and it was not obvious to Warboys exactly how they were being propelled.

Daring to stand up, Warboys reached for the great balloon, expecting it to be soft like a mattress, but instead finding it firm as muscle. He teetered over to the deck rail and followed it along, toward the prow. There, the only polished bit of her, was the ship’s name – A.S. Hildegaard.

‘Hilda!’ laughed Warboys, remembering his dad trailing below. ‘Here, Dad! She’s named after Nana Warboys! What do you reckon to—’

Bill roared as the Hildegaard hit the wind off the river, and lofted into the sky.

‘Oh shit!’

Warboys went to haul at the rope, trying to pull his dad aboard. Below, the bewildered bridgemaster came out of his box, spilling a steaming mug of tea. Over the river and down through a market square the Hildegaard sank. Bill’s boots kicked at chimney pots, slithering on tiles and gutters as he managed to throw himself aboard the gondola. There he floundered into Warboys – and, as the two men fell heavily against the starboard rail, the Hildegaard leaned, turning hard about towards the city centre.

Warboys recognised Salt Row below as the Hildegaard swept down, nudging streetlamps out as she went. Both Warboys cowered as the balloon rammed a shop front, raking off the awning. The rebound dragged a gutter away as the aft ploughed through the canopies of deserted market stalls, overturning a covered spice cart, which smashed through the glass front of an office. Only then did the Hildegaard slow, sheltered for a moment between the two buildings.

Bill gaped at Warboys.

‘Get off, you daft sod,’ he yelled, ‘whilst the wind’s down!’

Lights popped on. Figures appeared in windows and doorways.

‘Call the watch!’ screamed a fearful lady, clutching at her night dress. The spice trader emerged to see what had happened, his mouth opening in silence at the mass looming over his storefront. Bill waved irritably at him. ‘Oi! Numbnuts! Don’t just stand there gawping! Come and help us! Catch one of these anchor lines!’

The spice trader yelled back, and before long Bill was in a heated argument with him. Warboys rolled his eyes, and suddenly felt a determination not to come down. With the ship still in a lull, he scoured the deck again, hoping for some control that would lift him up and away. In the shadow of the aft deck he spotted several soggy squares of paper. Edging toward them, he found a manual, face down and open, as if it had been dropped there.

Peeling it off the deck, he scooped up the loose sheets, glimpsing a jumbled mass of equations marked up with some strange foreign script. Didn’t look like any normal sort of manual. Then the Hildegaard jerked to a stop, toppling him over.

‘Here, son!’ said Bill. ‘They’ve set it fast!’ Warboys staggered to peer over the rail. The bewildered spice merchant had recruited some passers-by and managed to set a tether to the overturned cart.

‘Is there a windlass or summat about, son?’

Warboys sighed. His grip tightened on the soggy manual as he thought of potatoes and factories and allotments. He saw a cleaver down by the hold, and took it.

‘Son?’

Warboys lifted the cleaver.

‘Here, what are you doing?’ cried Bill, as the blade thumped down and cut the rope. His cry was strangled as the Hildegaard was hooked away by a gust blasting down Courtway. The balloon expanded as if by sudden inhalation, and a bilious stench flooded the deck as the Hildegaard rose, its ascent yanking sharply at Warboys’ stomach. Bill clung to the ratlines in terror.

Chimney pots passed them by, as they shot up through the layer of greasy smog that hung over town. The monstrous viaduct reared, scaffolds glistening in its flanks, but even this giant sank at alarming rate, revealing the warehouses and timber yards that sprawled beyond it. Warboys’ eyes watered in the wind, and for a time he forgot the streets, rising high enough to see the fading fire of day still burning on the horizon. The light of the wider world beyond. He felt a moment of breathless freedom on sight of this luminous frontier, a feeling he’d not felt since childhood.

‘Look at that bloody view!’ cackled Bill, pointing north. There, the land rose steadily toward the border with Andamark, where the white tipped mountains of the Andavirke Pass hinted at the icy masses of the polar straits beyond. To the west, the vast plains disappeared into night, rising towards the Eldask – the great mountainous woodlands that spined the continent and, even now, defied incursion. Warboys had read legends of the Old Eldask as a boy, and now found himself thrilled to see signs of it for real. Their southern vista opened up into a churlish mass of grey sea, and even though he knew it was more than a thousand miles away, he imagined that the blurry, fragmented coastline showed hints of the curled tail of the Wyvern Peninsula, something he’d only seen on maps. All these places that had once just been names, idle blather, now suddenly seemed suddenly so present, so available.

For a time, father and son clung to one another in dumb awe.

Then there was a sharp snap, and a tiny flower of splinters appeared in the deck. The two looked from the mark to one another. A pop above, and a pock-mark appeared in the balloon. The Hildegaard hissed and began to sink, along with Warboys’ heart. The viaduct reared again, the steeples and towers jabbing up, and through the wind Warboys heard a commanding voice. He peered over the deckrail to the cobbles below, where an infantry squad trampled into formation, dull green coats and rifles at the ready. A crowd of onlookers trailed along.

‘Daft buggers are shooting at us!’ said Bill.

‘Take aim, lads!’ bellowed the sergeant, forcing Warboys’ heart into his mouth. They cowered, and the gasbag vented away, flooding the deck with that horrendous stench. It was slim consolation to think they might be gassed before they were shot dead. The Hildegaard nudged the steeple on the corner of Nix Steer, and swivelled, leaving Warboys within arm’s reach of the chimney pots. He briefly wondered if they could make a run for it over the rooftops. Then another shot split the decking near his eye.

‘Stop!’ yelled Warboys, compelled by fear. ‘Men on board!’

He stuffed the manual inside his coat before he arose, arms raised. Bill followed his lead, reluctantly.

‘Oi!’ bawled the sergeant. ‘You up there! You’d better show yourself now!’

‘Alright, son. Just stay steady, now.’

‘Tether the thing,’ commanded the sergeant. ‘And get those idiots down. Arrest them.’

‘What for?’ Bill objected.

‘Hijacking.’

‘You what? We’re no bloody hijackers! My son was just on his way home, like, and it… it came for him…’

‘I was just trying to stop the bloody thing!’

The troops caught the trailing rigs, and the Hildegaard bobbed as she began to be hauled down.

‘Get them down, and hold them. I want them and the ship searched.’

Warboys wondered what they were so desperate to find, if not just the ship itself. He patted the manual in his coat. Is it this?

‘Bollocks to this,’ said Warboys, turning and hauling at the first lever he could find.

‘Don’t—’

The Hildegaard issued a dull farting sound before lofting away down the row, dragging the troops through a stall and scraping them away.

Bill turned on Warboys. ‘You bloody pillock! What the hell are you thinking?’

‘You want to get arrested, do you?’

‘No, but… what do we do now?’

‘I don’t know. Let’s try and get her out of the way a bit. Pull levers. Turn the wheel about and that.’

They busied themselves with this. Bill loosened a valve and a quick burst of gas buoyed them as Warboys turned the wheel hard about. It was enough to bring them circling back over the river back towards Kingstown. They sailed in a big daft spiral, away from the streetlights to the dark spaces of the allotments.

The bow pushed a shed over, snapped the frames of someone’s runner beans, and tipped over a water butt before ploughing a furrow through a potato patch. Warboys was thrown overboard acoss a compost heap, and the deflating balloon lolled over him, flattening several plots at once.

There was calm. Bill scrambled out and took a breath before assessing the damage.

‘It’s a bloody good job you didn’t land it on my plot! I’d have wrung your fucking neck!’

‘Thank-you, Father,’ said Warboys, emerging dizzily. ‘But don’t worry yourself. I’m not hurt.’

‘Aye, well. I should shut your mouth if I was you.’

Warboys teetered, still feeling the sensation of flight in his knees, and leaned against a fence. For a time, they said nothing. Then Bill looked at Warboys and, seeing his peaky face, burst out laughing.

‘What?’

‘Your face, when they put them muzzles on you! Saw your own arse then, didn’t you? Ha! Fancied yourself as the captain going down with his ship, didn’t yer? Ha! You big prat! Come on. Let’s go, before they catch up.’

Warboys ignored him, looked around. A few dazed looking gardeners had gathered to stare, and the soldiers wouldn’t be far behind. Warboys pulled out the manual and opened it. Each page showed wax rubbings of some ornate script, set in a language he couldn’t begin to fathom. Only the inked annotations at the foot of the page indicated which way up the sheet went. He leafed through the pages filled with odd geometric patterns and arrays. The back of each leaf was stamped PROPERTY OF THE AERONAUTICS DIVISION. Some of the arrays resembled some kind of starchart, but he couldn’t be sure – and even the annotations revealed little. Most seemed to list cross references of some sort, other volumes, page numbers and so on. But there were some vaguely mechanical notes – cord masses, engine stems, anterior flukes, ventral valves, and airscrew housing tract, types A and B.

Bill came staggering around.

‘Come on! What are you looking at?’

‘It’s like a manual. For the airships, I think.’

‘Leave it, daft lad! They’ll be here any minute! Come on!’

‘Alright, alright.’

Bill turned to leave. Warboys staggered after him, glancing back at the bizarre scale of the airship now sagging over the plots. He grinned, broadly. Looking farther afield, he saw the chimneys and rows of the town all around yet again, at odds with that grand feeling of freedom that still fizzed in his legs. He couldn’t, wouldn’t throw that away. Not entirely. Slyly, he shoved the manual inside his coat.

‘Come on!’ demanded Bill. ‘I need a pint.’

‘Alright! Bloody hell!’

They fled into the streets. Warboys felt the manual’s edge through the lining of his pocket, and wondered what he’d just nicked off with.

4

A LOVELY PAIR

Warboys had been giddy by the time they’d arrived at the Blackwater tavern. There was nothing like narrow survival and death defying flight to make a man thirsty. He’d figured a little celebratory drink would warm him up a bit before he got to wondering what to do with his fancy manual.

Too many pints later, Warboys awoke to the onset of pins and needles in his arse, and peeled his face up off the bar.

‘Public Responsibility, my arse!’ came Bill’s voice. They’d agreed on the doorstep not to speak of the Hildegaard, and Bill seemed to have resumed normal service, having been droning on at his mates for hours now. ‘Modern State! It’s a bloody wilderness we’re heading for, I tell yer, steam engines or airships or not!’

There were moans of agreement from Bill’s mates as the taproom flexed before Warboys, congealing like a bad old memory: the Blackwater Tavern. His local. Thick as ever with smoke and the warm hum of beer, rain still tapping the windows, a hangover already throbbing, and old codgers setting the world to rights.

Just like the old days.

‘“Modern man is a soldier,” he says,’ continued Bill. ‘Don’t make me laugh!’

Through screwed eyes, Warboys sought the new barmaid he’d been eyeing before he’d lost consciousness – but she’d long since clocked off. Only Sourpus Jib remained, a shrivelled veteran sailor who worked the bar for free drinks. Jib gave him a nod and went on sucking at vinegary cockles with all of the three teeth left in his head. Belatedly, Warboys remembered the manual, the recollection echoing the giddy feeling of flight. He patted his coat, relieved to find it was still there.

‘Book clutching Malvyites,’ Bill went on, ‘too busy with their high ideals to realise we’re up to the knees in shite. Who the bloody ‘ell are these Modern Soldiers?’

Warboys stood to attend the prickly fire in his backside. In the speckled mirror of an old tankard he saw his heavy brow collide with the long since broken nose, setting an angry looking knot in his countenance. The throb of a new bruise fattened one eye where Ives had jabbed him.

‘And then you’ve got these lads,’ said Bill, ‘what can’t see no further than the dregs at the bottom of their pint, as if the world’s all found and finished doin’ what it meant, and these kids just want stuffin’ with bread and beer before the end of their days. Soft fucking heads they’ve got, ripe for drafting. Aye. Caught this country napping, Malvy has.’

There were more inarticulate murmurs of approval. Warboys braced himself.

‘Is this a pub or a bastard lecture ’ouse? You’re giving me ’eadache.’

Warboys turned round. Bill raised his glass.

‘Here it is, look. The fruit of my loins! What a bloody sight. One hand on his beer, t’other on his arse.’

‘Piss off,’ moaned Warboys. ‘I’m asleep.’

Bill drained his pint, whilst the other codgers stared as if Warboys were a caged ape on the menagerie.

‘Anyways,’ cut in Norris Hooks, a stubbly man in a tall-hat, keen to resume the issue of the day, ‘it ain’t proper war. I mean, everybody knows there’s been upstarts in Blackhaven for years! The blacklanders hate us, and always have. That’s nowt new.’

‘You’re not wrong, Norris,’ said Bill. ‘I don’t believe there are any boody rebels. This is all just so Malvy can get everyone marching to his tune.’

‘That’s it, Bill. I mean, y’can’t invade your own country, can you? He just wants a show of force, like.’

‘Aye,’ scoffed Bill, ‘and a bloody show it’ll be. Even if he gets Blackhaven back, and goes out to all them fiddly little islands down there – there ain’t enough room to stick a fucking flag in some of ’em. It can’t be done, and it ain’t worth doin’ anyhow.’

‘It might be now,’ grunted Rutger, a squat fellow with thick, soiled hands, ‘what with all these new flyers.’

Warboys considered this a moment. Wondered just how valuable the manual was. Maybe he could fence it back to Malvy’s aeronautics people. His mate Sykes had a few contacts out of town.

‘Yah!’ said Bill. ‘Flyers! I’ve seen what good they are! Good for hangin’ washin’ off of!’

Warboys locked eyes with his father. He didn’t expect the old sod to run off and enlist in the air force, but after their experience on the Hildegaard together, something about this public denouncement in front of Bill’s mates got his back up.

‘They could change the world, these airships,’ he said, holding the old man’s eye.

‘Give over! They can’t even steer them right. A fine fucking airforce that is, when you have your own troops running about shooting after your vessels.’

‘Well, they haven’t fixed it right yet, have they? You’ve got to be open to advancement, Father.’

‘Advancements. Still got a draught in your skull, you have.’

‘See, you’re the one moanin’ on about how the world lost its guts, and how no bastard wants to make an effort no more, yet you’re sat knocking it all! There’s all the world out there!’

‘It’s Malvy’s world out there now. The Andwyke War was a fight for life. For our country and our livelihood. Now, we’re just a load of engine parts. The world’s gone backwards into slavery, and some silly bastards can’t see it cos they’re too busy floating in the fucking clouds!’

At this, the codgers took a step back, looking from one Warboys to the other as the tension became palpable.

‘You’ve never ’ad any imagination,’ said Warboys, dismissively.

‘Imagination! What about you? All them jobs I had to find for you never came to you through imagination, did they lad? And was it imagination what’s stopped you ’oldin down a single bastard one of ’em? Eh? Bollocks to your imagination.’

Bill tore away, and fumed privately a moment, whilst he rolled a smoke. Then he cleared his throat.

‘Anyway. I was just saying to these gents about your work situation.’

‘Oh you were, were you?’

Bill puffed himself up for his mates.

‘You’re going to have to watch yourself. They’ve drafted thousands already! New People’s Infantry, he calls it. Fucking shambles I call it.’

‘Aye,’ snorted Rutger. ‘A lump like him, with no papers? He’ll be marching down on the Wyvern before long! Get yourself a sun-tan, boy!’

‘He’ll not get a tan in the Blacklands. Footrot, more like.’

‘He will down past the peninsula, on the islands. They got terr-marters and all sorts down there.’

‘Make a good batterin ram, he would!’

‘Will you lot shut your faces? I aren’t going down south.’

‘Hark at Lord Warboys here! Well listen. No-one’s safe. This Public Responsibility Act says if you haven’t got a use then you haven’t got a right, see? Even royalty, like you. There’s been a raid a day at some aristocrat’s house or other. There was a bloody firefight at the Duke of Bernigny’s manor, and the next day, posters went up denouncing Bernigny as a traitor. So I’ll tell you for nowt, your best bet’s to get straight into some solid work.’

‘Don’t start on about them bloody taty fields again, alright? I’ll sort me self out.’

Bill went red in the face, and Warboys’ gut turned over again with the sinking feeling that the trip out to sea had never happened. ‘Picky are you? I tell you what, son, the likes of us will just graft while you put your feet up, eh?’

‘Don’t start chowing at me. I’m just not going to work on that taty plant, and that’s the end of it.’

Bill wielded his fist. ‘Yeah, carry on. I’ll give you another black eye in a minute, make a lovely pair. You can turn and jump back in the dock for me! Go on. Piss off in one o’ yer precious flyers!’

Warboys did not reply. Bill glared, a mixture of concern and anger vying for him again. He took a breath, making a hard effort to compose himself.

‘Listen. I’ll go down the guild first thing. See If I can get you summat.’

‘Fine, Dad. Just not the taties, alright?’

‘Is it ’cos of your mother?’

‘No, Father,’ snapped Warboys. ‘It’s because I’ve eaten so much mash lately and I’m a bit fed up of it.’

‘Oh, you’re a clever little shit aren’t you? You should have a bit more respect for your Mother’s memory!’

‘That’s the point, isn’t it?’ snarled Warboys, slamming down his ale. ‘I do!’

Warboys looked at them all gawping, heard Sourpus Jib’s vinegary chuckling, the same old tankards gathering dust above the bar. A sickly, trapped feeling throbbed in his chest, and suddenly, he couldn’t bear it any longer.

‘Ah, fuck off, the lot of yer! Let me out of this shithole, for god’s sake.’

And with that, he stormed outside, clutching the manual inside his coat.

~ ~ ~

Warboys marched out over shimmering cobbles into the rain, and was soaked to the skin in seconds. He tramped past a cart as it pulled onto the green, dropping off bedraggled potato pickers, who filed away in a tiresome, mud-caked procession. The smell of fresh, wet soil came with them, and with it, suddenly, the bittersweet recollection of his mother.

Lily Warboys.

He could hardly remember her face now. He could picture her wrestling into her grimy shirt and the old potato smock. No face, only the ruffle of the workshirt as she’d shaken it over herself, the whisper of her hair as she tied it back, and her hands, which he could remember best of all. Lily Warboys had rough, dry hands, strong hands. He recalled the row every morning, as old Martha Steeples and Izzy Corden came calling on the way, smoking heavily, cackling at the tops of their voices. He’d follow their procession past Kings Corner and down Salt Row, great regiments of women wearing the long, soiled uniforms of the potato fields. She’d leave him at the tall, arched iron gate, shoo him off on his way to Nana Warboys’ house. And then she’d meet him there again in the evenings, thick with the smell of fresh soil, her hands lined with dirt.

He recalled the feel of her hand in his, caressing it with his thumb on the walk home.

He recalled the sandpaper slap of it on his face when she lost her temper.

He remembered the summers, when they’d go with Nana Warboys down to the horsewash on the Jet, wading in the mud at low tide, looking for flatties and winkles in the tidal pools left under the hulls of barges, and among the mops of bladderack on the pilings. Lily with her skirts up around her knees, mud caking her calves. Nana Warboys washing their feet in a bucket in the yard, barely able to crawl off to bed they were so tired.

Lily never let him go to wave the old man off when he sailed. She’d avoid Bill’s eye, and carry on in her stiff-lipped way, as if it couldn’t matter. But they always queued to await his return – Lily always acknowledged the old man’s return – and Warboys remembered the nights when his dad was first home, singing on the back step, the sound of Mr. South’s concertina drifting across the way. Fresh crabs for Nana Warboys, the crack as she laid into them with a claw hammer and sucked the flesh out with toothless contentment.

Bill came and went, and the time came when Warboys became too much for Nana Warboys to look after. He was taken with Lily, given a smock of his own, and queued outside the gate with the dusty smell of soil curling around him. Soil of his own in the lines of his knuckles. The spuds went from hands to pouch, barrows to carriage, and the carriage was walked by cart to a tramline that ran through the yards to the canal, ready to be pulled by horse. A great iron hopper stood there to load, ready for the steamer to come.

Sometimes the hopper would choke on the load, and someone would have to climb up and loosen potatoes at the neck. One day Lily went up there to free up a blockage, not realising that the hopper hadn’t been sealed first. Down she’d gone, with the avalanche of potatoes giving way beneath her feet.

He remembered the clang as her head caught the side of the hopper, a resounding, final gong, and the ignoble tumbling of spuds over the tracks. They’d all seen her slide out, borne along on a rolling sheet of taters. Izzy Corden nudged Marta Biel, ready to wet themselves laughing.

But Lily didn’t move, even as more spuds rolled down over her. The blow to the head had killed her before she’d hit the floor, and the potatoes lent the whole thing an indignity with which Warboys had never quite come to terms.

So there was another parade. Martha Steeples and Izzy Corden called, hanging their heads now, their shirts as clean and pressed as could be managed. That time, Lily Warboys lay in a coffin ahead of them, while Bill – fresh from sea to the news that very morning, and still awash with salt – gathered himself to bear the coffin. Warboys remembered the springy haired back of his father’s head as he carried the box. The gaffer paid half her last day’s wages, put against the cost of a headstone. Warboys remembered the feel of Bill’s hands gouging in his hair, as if trying to recover some traces of Lily’s form in the dust that had settled there.

He couldn’t recall her face, even now. He’d stood and looked at the casket, but couldn’t look at her face. His eyes had fallen to find those hands that were somehow more expressive than the face could ever be. There lay Lily Warboys, still with traces of dirt in the creases of her skin. He hadn’t known at the time what upset him more: that they’d been careless enough to leave dirt on her, or that they’d tried to brush her up, change her, make her seem as if she’d never spent every day of her life smeared in soil. But either way, the anger stayed with him, itching like the soil in the cracks of his knuckles.

The procession, the waiting, the thick, humid smell as she went into the ground after her potatoes. Bill pawed at him in grief, vowed to give up his sailing as soon as he could. Come home and be together.

The day after the funeral, Warboys found himself queuing up for the fields again, angry at the audacious continuity of it all. When the gaffer’s son came to usher him, all mouthy with thin authority, young Warboys broke from his stupor like a drowning man hitting the surface, took the weedy boy down to the soil, shoulder working like a steam piston as his blows rained down, to the shocked silence of the workers. And so Warboys ruined his first job.