Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

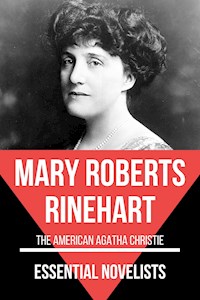

- Herausgeber: Phoemixx Classics Ebooks

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

The Bat Mary Roberts Rinehart - The Bat is a three-act play by Mary Roberts Rinehart that was first produced by Lincoln Wagenhals and Collin Kemper in 1920. The story combines elements of mystery and comedy as Cornelia Van Gorder and guests spend a stormy night at her rented summer home, searching for stolen money they believe is hidden in the house, while they are stalked by a masked criminal known as "the Bat". The Bat's identity is revealed at the end of the final act.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 308

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PUBLISHER NOTES:

Quality of Life, Freedom, More time with the ones you Love.

Visit our website: LYFREEDOM.COM

Chapter

1

THE SHADOW OF THE BAT

"You've got to get him, boys—get him or bust!" said a tired police chief, pounding a heavy fist on a table. The detectives he bellowed the words at looked at the floor. They had done their best and failed. Failure meant "resignation" for the police chief, return to the hated work of pounding the pavements for them—they knew it, and, knowing it, could summon no gesture of bravado to answer their chief's. Gunmen, thugs, hi-jackers, loft-robbers, murderers, they could get them all in time—but they could not get the man he wanted.

"Get him—to hell with expense—I'll give you carte blanche—but get him!" said a haggard millionaire in the sedate inner offices of the best private detective firm in the country. The man on the other side of the desk, man hunter extraordinary, old servant of Government and State, sleuthhound without a peer, threw up his hands in a gesture of odd hopelessness. "It isn't the money, Mr. De Courcy—I'd give every cent I've made to get the man you want—but I can't promise you results—for the first time in my life." The conversation was ended.

"Get him? Huh! I'll get him, watch my smoke!" It was young ambition speaking in a certain set of rooms in Washington. Three days later young ambition lay in a New York gutter with a bullet in his heart and a look of such horror and surprise on his dead face that even the ambulance-Doctor who found him felt shaken. "We've lost the most promising man I've had in ten years," said his chief when the news came in. He swore helplessly, "Damn the luck!"

"Get him—get him—get him—get him!" From a thousand sources now the clamor arose—press, police, and public alike crying out for the capture of the master criminal of a century—lost voices hounding a specter down the alleyways of the wind. And still the meshes broke and the quarry slipped away before the hounds were well on the scent—leaving behind a trail of shattered safes and rifled jewel cases—while ever the clamor rose higher to "Get him—get him—get—"

Get whom, in God's name—get what? Beast, man, or devil? A specter—a flying shadow—the shadow of a Bat.

From thieves' hangout to thieves' hangout the word passed along stirring the underworld like the passage of an electric spark. "There's a bigger guy than Pete Flynn shooting the works, a guy that could have Jim Gunderson for breakfast and not notice he'd et." The underworld heard and waited to be shown; after a little while the underworld began to whisper to itself in tones of awed respect. There were bright stars and flashing comets in the sky of the world of crime—but this new planet rose with the portent of an evil moon.

The Bat—they called him the Bat. Like a bat he chose the night hours for his work of rapine; like a bat he struck and vanished, pouncingly, noiselessly; like a bat he never showed himself to the face of the day. He'd never been in stir, the bulls had never mugged him, he didn't run with a mob, he played a lone hand, and fenced his stuff so that even the fence couldn't swear he knew his face. Most lone wolves had a moll at any rate—women were their ruin—but if the Bat had a moll, not even the grapevine telegraph could locate her.

Rat-faced gunmen in the dingy back rooms of saloons muttered over his exploits with bated breath. In tawdrily gorgeous apartments, where gathered the larger figures, the proconsuls of the world of crime, cold, conscienceless brains dissected the work of a colder and swifter brain than theirs, with suave and bitter envy. Evil's Four Hundred chattered, discussed, debated—sent out a thousand invisible tentacles to clutch at a shadow—to turn this shadow and its distorted genius to their own ends. The tentacles recoiled, baffled—the Bat worked alone—not even Evil's Four Hundred could bend him into a willing instrument to execute another's plan.

The men higher up waited. They had dealt with lone wolves before and broken them. Some day the Bat would slip and falter; then they would have him. But the weeks passed into months and still the Bat flew free, solitary, untamed, and deadly. At last even his own kind turned upon him; the underworld is like the upper in its fear and distrust of genius that flies alone. But when they turned against him, they turned against a spook—a shadow. A cold and bodiless laughter from a pit of darkness answered and mocked at their bungling gestures of hate—and went on, flouting Law and Lawless alike.

Where official trailer and private sleuth had failed, the newspapers might succeed—or so thought the disillusioned young men of the Fourth Estate—the tireless foxes, nose-down on the trail of news—the trackers, who never gave up until that news was run to earth. Star reporter, leg-man, cub, veteran gray in the trade—one and all they tried to pin the Bat like a caught butterfly to the front page of their respective journals—soon or late each gave up, beaten. He was news—bigger news each week—a thousand ticking typewriters clicked his adventures—the brief, staccato recital of his career in the morgues of the great dailies grew longer and more incredible each day. But the big news—the scoop of the century—the yearned-for headline, "Bat Nabbed Red-Handed", "Bat Slain in Gun Duel with Police"—still eluded the ravenous maw of the Linotypes. And meanwhile, the red-scored list of his felonies lengthened and the rewards offered from various sources for any clue which might lead to his apprehension mounted and mounted till they totaled a small fortune.

Columnists took him up, played with the name and the terror, used the name and the terror as a starting point from which to exhibit their own particular opinions on everything and anything. Ministers mentioned him in sermons; cranks wrote fanatic letters denouncing him as one of the even-headed beasts of the Apocalypse and a forerunner of the end of the world; a popular revue put on a special Bat number wherein eighteen beautiful chorus girls appeared masked and black-winged in costumes of Brazilian bat fur; there were Bat club sandwiches, Bat cigarettes, and a new shade of hosiery called simply and succinctly Bat. He became a fad—a catchword—a national figure. And yet—he was walking Death—cold—remorseless. But Death itself had become a toy of publicity in these days of limelight and jazz.

A city editor, at lunch with a colleague, pulled at his cigarette and talked. "See that Sunday story we had on the Bat?" he asked. "Pretty tidy—huh—and yet we didn't have to play it up. It's an amazing list—the Marshall jewels—the Allison murder—the mail truck thing—two hundred thousand he got out of that, all negotiable, and two men dead. I wonder how many people he's really killed. We made it six murders and nearly a million in loot—didn't even have room for the small stuff—but there must be more—"

His companion whistled.

"And when is the Universe's Finest Newspaper going to burst forth with 'Bat Captured by BLADE Reporter?'" he queried sardonically.

"Oh, for—lay off it, will you?" said the city editor peevishly. "The Old Man's been hopping around about it for two months till everybody's plumb cuckoo. Even offered a bonus—a big one—and that shows how crazy he is—he doesn't love a nickel any better than his right eye—for any sort of exclusive story. Bonus—huh!" and he crushed out his cigarette. "It won't be a Blade reporter that gets that bonus—or any reporter. It'll be Sherlock Holmes from the spirit world!"

"Well—can't you dig up a Sherlock?"

The editor spread out his hands. "Now, look here," he said. "We've got the best staff of any paper in the country, if I do say it. We've got boys that could get a personal signed story from Delilah on how she barbered Samson—and find out who struck Billy Patterson and who was the Man in the Iron Mask. But the Bat's something else again. Oh, of course, we've panned the police for not getting him; that's always the game. But, personally, I won't pan them; they've done their damnedest. They're up against something new. Scotland Yard wouldn't do any better—or any other bunch of cops that I know about."

"But look here, Bill, you don't mean to tell me he'll keep on getting away with it indefinitely?"

The editor frowned. "Confidentially—I don't know," he said with a chuckle: "The situation's this: for the first time the super-crook—the super-crook of fiction—the kind that never makes a mistake—has come to life—real life. And it'll take a cleverer man than any Central Office dick I've ever met to catch him!"

"Then you don't think he's just an ordinary crook with a lot of luck?"

"I do not." The editor was emphatic. "He's much brainier. Got a ghastly sense of humor, too. Look at the way he leaves his calling card after every job—a black paper bat inside the Marshall safe—a bat drawn on the wall with a burnt match where he'd jimmied the Cedarburg Bank—a real bat, dead, tacked to the mantelpiece over poor old Allison's body. Oh, he's in a class by himself—and I very much doubt if he was a crook at all for most of his life."

"You mean?"

"I mean this. The police have been combing the underworld for him; I don't think he comes from there. I think they've got to look higher, up in our world, for a brilliant man with a kink in the brain. He may be a Doctor, a lawyer, a merchant, honored in his community by day—good line that, I'll use it some time—and at night, a bloodthirsty assassin. Deacon Brodie—ever hear of him—the Scotch deacon that burgled his parishioners' houses on the quiet? Well—that's our man."

"But my Lord, Bill—"

"I know. I've been going around the last month, looking at everybody I knew and thinking—are you the Bat? Try it for a while. You'll want to sleep with a light in your room after a few days of it. Look around the University Club—that white-haired man over there—dignified—respectable—is he the Bat? Your own lawyer—your own Doctor—your own best friend. Can happen you know—look at those Chicago boys—the thrill-killers. Just brilliant students—likeable boys—to the people that taught them—and cold-blooded murderers all the same."

"Bill! You're giving me the shivers!"

"Am I?" The editor laughed grimly. "Think it over. No, it isn't so pleasant.—But that's my theory—and I swear I think I'm right." He rose.

His companion laughed uncertainly.

"How about you, Bill—are you the Bat?"

The editor smiled. "See," he said, "it's got you already. No, I can prove an alibi. The Bat's been laying off the city recently—taking a fling at some of the swell suburbs. Besides I haven't the brains—I'm free to admit it." He struggled into his coat. "Well, let's talk about something else. I'm sick of the Bat and his murders."

His companion rose as well, but it was evident that the editor's theory had taken firm hold on his mind. As they went out the door together he recurred to the subject.

"Honestly, though, Bill—were you serious, really serious—when you said you didn't know of a single detective with brains enough to trap this devil?"

The editor paused in the doorway. "Serious enough," he said. "And yet there's one man—I don't know him myself but from what I've heard of him, he might be able—but what's the use of speculating?"

"I'd like to know all the same," insisted the other, and laughed nervously. "We're moving out to the country next week ourselves—right in the Bat's new territory."

"We-el," said the editor, "you won't let it go any further? Of course it's just an idea of mine, but if the Bat ever came prowling around our place, the detective I'd try to get in touch with would be—" He put his lips close to his companion's ear and whispered a name.

The man whose name he whispered, oddly enough, was at that moment standing before his official superior in a quiet room not very far away. Tall, reticently good-looking and well, if inconspicuously, clothed and groomed, he by no means seemed the typical detective that the editor had spoken of so scornfully. He looked something like a college athlete who had kept up his training, something like a pillar of one of the more sedate financial houses. He could assume and discard a dozen manners in as many minutes, but, to the casual observer, the one thing certain about him would probably seem his utter lack of connection with the seamier side of existence. The key to his real secret of life, however, lay in his eyes. When in repose, as now, they were veiled and without unusual quality—but they were the eyes of a man who can wait and a man who can strike.

He stood perfectly easy before his chief for several moments before the latter looked up from his papers.

"Well, Anderson," he said at last, looking up, "I got your report on the Wilhenry burglary this morning. I'll tell you this about it—if you do a neater and quicker job in the next ten years, you can take this desk away from me. I'll give it to you. As it is, your name's gone up for promotion today; you deserved it long ago."

"Thank you, sir," replied the tall man quietly, "but I had luck with that case."

"Of course you had luck," said the chief. "Sit down, won't you, and have a cigar—if you can stand my brand. Of course you had luck, Anderson, but that isn't the point. It takes a man with brains to use a piece of luck as you used it. I've waited a long time here for a man with your sort of brains and, by Judas, for a while I thought they were all as dead as Pinkerton. But now I know there's one of them alive at any rate—and it's a hell of a relief."

"Thank you, sir," said the tall man, smiling and sitting down. He took a cigar and lit it. "That makes it easier, sir—your telling me that. Because—I've come to ask a favor."

"All right," responded the chief promptly. "Whatever it is, it's granted."

Anderson smiled again. "You'd better hear what it is first, sir. I don't want to put anything over on you."

"Try it!" said the chief. "What is it—vacation? Take as long as you like—within reason—you've earned it—I'll put it through today."

Anderson shook his head, "No sir—I don't want a vacation."

"Well," said the chief impatiently. "Promotion? I've told you about that. Expense money for anything—fill out a voucher and I'll O.K. it—be best man at your wedding—by Judas, I'll even do that!"

Anderson laughed. "No, sir—I'm not getting married and—I'm pleased about the promotion, of course—but it's not that. I want to be assigned to a certain case—that's all."

The chief's look grew searching. "H'm," he said. "Well, as I say, anything within reason. What case do you want to be assigned to?"

The muscles of Anderson's left hand tensed on the arm of his chair. He looked squarely at the chief. "I want a chance at the Bat!" he replied slowly.

The chief's face became expressionless. "I said—anything within reason," he responded softly, regarding Anderson keenly.

"I want a chance at the Bat!" repeated Anderson stubbornly. "If I've done good work so far—I want a chance at the Bat!"

The chief drummed on the desk. Annoyance and surprise were in his voice when he spoke.

"But look here, Anderson," he burst out finally. "Anything else and I'll—but what's the use? I said a minute ago, you had brains—but now, by Judas, I doubt it! If anyone else wanted a chance at the Bat, I'd give it to them and gladly—I'm hard-boiled. But you're too valuable a man to be thrown away!"

"I'm no more valuable than Wentworth would have been."

"Maybe not—and look what happened to him! A bullet hole in his heart—and thirty years of work that he might have done thrown away! No, Anderson, I've found two first-class men since I've been at this desk—Wentworth and you. He asked for his chance; I gave it to him—turned him over to the Government—and lost him. Good detectives aren't so plentiful that I can afford to lose you both."

"Wentworth was a friend of mine," said Anderson softly. His knuckles were white dints in the hand that gripped the chair. "Ever since the Bat got him I've wanted my chance. Now my other work's cleaned up—and I still want it."

"But I tell you—" began the chief in tones of high exasperation. Then he stopped and looked at his protege. There was a silence for a time.

"Oh, well—" said the chief finally in a hopeless voice. "Go ahead—commit suicide—I'll send you a 'Gates Ajar' and a card, 'Here lies a damn fool who would have been a great detective if he hadn't been so pig-headed.' Go ahead!"

Anderson rose. "Thank you, sir," he said in a deep voice. His eyes had light in them now. "I can't thank you enough, sir."

"Don't try," grumbled the chief. "If I weren't as much of a damn fool as you are I wouldn't let you do it. And if I weren't so damn old, I'd go after the slippery devil myself and let you sit here and watch me get brought in with an infernal paper bat pinned where my shield ought to be. The Bat's supernatural, Anderson. You haven't a chance in the world but it does me good all the same to shake hands with a man with brains and nerve," and he solemnly wrung Anderson's hand in an iron grip.

Anderson smiled. "The cagiest bat flies once too often," he said. "I'm not promising anything, chief, but—"

"Maybe," said the chief. "Now wait a minute, keep your shirt on, you're not going out bat hunting this minute, you know—"

"Sir? I thought I—"

"Well, you're not," said the chief decidedly. "I've still some little respect for my own intelligence and it tells me to get all the work out of you I can, before you start wild-goose chasing after this—this bat out of hell. The first time he's heard of again—and it shouldn't be long from the fast way he works—you're assigned to the case. That's understood. Till then, you do what I tell you—and it'll be work, believe me!"

"All right, sir," Anderson laughed and turned to the door. "And—thank you again."

He went out. The door closed. The chief remained for some minutes looking at the door and shaking his head. "The best man I've had in years—except Wentworth," he murmured to himself. "And throwing himself away—to be killed by a cold-blooded devil that nothing human can catch—you're getting old, John Grogan—but, by Judas, you can't blame him, can you? If you were a man in the prime like him, by Judas, you'd be doing it yourself. And yet it'll go hard—losing him—"

He turned back to his desk and his papers. But for some minutes he could not pay attention to the papers. There was a shadow on them—a shadow that blurred the typed letters—the shadow of bat's wings.

Chapter

2

THE INDOMITABLE MISS VAN GORDER

Miss Cornelis Van Gorder, indomitable spinster, last bearer of a name which had been great in New York when New York was a red-roofed Nieuw Amsterdam and Peter Stuyvesant a parvenu, sat propped up in bed in the green room of her newly rented country house reading the morning newspaper. Thus seen, with an old soft Paisley shawl tucked in about her thin shoulders and without the stately gray transformation that adorned her on less intimate occasions,—she looked much less formidable and more innocently placid than those could ever have imagined who had only felt the bite of her tart wit at such functions as the state Van Gorder dinners. Patrician to her finger tips, independent to the roots of her hair, she preserved, at sixty-five, a humorous and quenchless curiosity in regard to every side of life, which even the full and crowded years that already lay behind her had not entirely satisfied. She was an Age and an Attitude, but she was more than that; she had grown old without growing dull or losing touch with youth—her face had the delicate strength of a fine cameo and her mild and youthful heart preserved an innocent zest for adventure.

Wide travel, social leadership, the world of art and books, a dozen charities, an existence rich with diverse experience—all these she had enjoyed energetically and to the full—but she felt, with ingenious vanity, that there were still sides to her character which even these had not brought to light. As a little girl she had hesitated between wishing to be a locomotive engineer or a famous bandit—and when she had found, at seven, that the accident of sex would probably debar her from either occupation, she had resolved fiercely that some time before she died she would show the world in general and the Van Gorder clan in particular that a woman was quite as capable of dangerous exploits as a man. So far her life, while exciting enough at moments, had never actually been dangerous and time was slipping away without giving her an opportunity to prove her hardiness of heart. Whenever she thought of this the fact annoyed her extremely—and she thought of it now.

She threw down the morning paper disgustedly. Here she was at 65—rich, safe, settled for the summer in a delightful country place with a good cook, excellent servants, beautiful gardens and grounds—everything as respectable and comfortable as—as a limousine! And out in the world people were murdering and robbing each other, floating over Niagara Falls in barrels, rescuing children from burning houses, taming tigers, going to Africa to hunt gorillas, doing all sorts of exciting things! She could not float over Niagara Falls in a barrel; Lizzie Allen, her faithful old maid, would never let her! She could not go to Africa to hunt gorillas; Sally Ogden, her sister, would never let her hear the last of it. She could not even, as she certainly would if the were a man, try and track down this terrible creature, the Bat!

She sniffed disgruntledly. Things came to her much too easily. Take this very house she was living in. Ten days ago she had decided on the spur of the moment—a decision suddenly crystallized by a weariness of charitable committees and the noise and heat of New York—to take a place in the country for the summer. It was late in the renting season—even the ordinary difficulties of finding a suitable spot would have added some spice to the quest—but this ideal place had practically fallen into her lap, with no trouble or search at all. Courtleigh Fleming, president of the Union Bank, who had built the house on a scale of comfortable magnificence—Courtleigh Fleming had died suddenly in the West when Miss Van Gorder was beginning her house hunting. The day after his death her agent had called her up. Richard Fleming, Courtleigh Fleming's nephew and heir, was anxious to rent the Fleming house at once. If she made a quick decision it was hers for the summer, at a bargain. Miss Van Gorder had decided at once; she took an innocent pleasure in bargains. The next day the keys were hers—the servants engaged to stay on—within a week she had moved. All very pleasant and easy no doubt—adventure—pooh!

And yet she could not really say that her move to the country had brought her no adventures at all. There had been—things. Last night the lights had gone off unexpectedly and Billy, the Japanese butler and handy man, had said that he had seen a face at one of the kitchen windows—a face that vanished when he went to the window. Servants' nonsense, probably, but the servants seemed unusually nervous for people who were used to the country. And Lizzie, of course, had sworn that she had seen a man trying to get up the stairs but Lizzie could grow hysterical over a creaking door. Still—it was queer! And what had that affable Doctor Wells said to her—"I respect your courage, Miss Van Gorder—moving out into the Bat's home country, you know!" She picked up the paper again. There was a map of the scene of the Bat's most recent exploits and, yes, three of his recent crimes had been within a twenty-mile radius of this very spot. She thought it over and gave a little shudder of pleasurable fear. Then she dismissed the thought with a shrug. No chance! She might live in a lonely house, two miles from the railroad station, all summer long—and the Bat would never disturb her. Nothing ever did.

She had skimmed through the paper hurriedly; now a headline caught her eye. Failure of Union Bank—wasn't that the bank of which Courtleigh Fleming had been president? She settled down to read the article but it was disappointingly brief. The Union Bank had closed its doors; the cashier, a young man named Bailey, was apparently under suspicion; the article mentioned Courtleigh Fleming's recent and tragic death in the best vein of newspaperese. She laid down the paper and thought—Bailey—Bailey—she seemed to have a vague recollection of hearing about a young man named Bailey who worked in a bank—but she could not remember where or by whom his name had been mentioned.

Well—it didn't matter. She had other things to think about. She must ring for Lizzie—get up and dress. The bright morning sun, streaming in through the long window, made lying in bed an old woman's luxury and she refused to be an old woman.

"Though the worst old woman I ever knew was a man!" she thought with a satiric twinkle. She was glad Sally's daughter—young Dale Ogden—was here in the house with her. The companionship of Dale's bright youth would keep her from getting old-womanish if anything could.

She smiled, thinking of Dale. Dale was a nice child—her favorite niece. Sally didn't understand her, of course—but Sally wouldn't. Sally read magazine articles on the younger generation and its wild ways. "Sally doesn't remember when she was a younger generation herself," thought Miss Cornelia. "But I do—and if we didn't have automobiles, we had buggies—and youth doesn't change its ways just because it has cut its hair. Before Mr. and Mrs. Ogden left for Europe, Sally had talked to her sister Cornelia … long and weightily, on the problem of Dale." "Problem of Dale, indeed!" thought Miss Cornelia scornfully. "Dale's the nicest thing I've seen in some time. She'd be ten times happier if Sally wasn't always trying to marry her off to some young snip with more of what fools call 'eligibility' than brains! But there, Cornelia Van Gorder—Sally's given you your innings by rampaging off to Europe and leaving Dale with you all summer and you've a lot less sense than I flatter myself you have, if you can't give your favorite niece a happy vacation from all her immediate family—and maybe find her someone who'll make her happy for good and all in the bargain." Miss Cornelia was an incorrigible matchmaker.

Nevertheless, she was more concerned with "the problem of Dale" than she would have admitted. Dale, at her age, with her charm and beauty—why, she ought to behave as if she were walking on air, thought her aunt worriedly. "And instead she acts more as if she were walking on pins and needles. She seems to like being here—I know she likes me—I'm pretty sure she's just as pleased to get a little holiday from Sally and Harry—she amuses herself—she falls in with any plan I want to make, and yet—" And yet Dale was not happy—Miss Cornelia felt sure of it. "It isn't natural for a girl to seem so lackluster and—and quiet—at her age and she's nervous, too—as if something were preying on her mind—particularly these last few days. If she were in love with somebody—somebody Sally didn't approve of particularly—well, that would account for it, of course—but Sally didn't say anything that would make me think that—or Dale either—though I don't suppose Dale would, yet, even to me. I haven't seen so much of her in these last two years—"

Then Miss Cornelia's mind seized upon a sentence in a hurried flow of her sister's last instructions—a sentence that had passed almost unnoticed at the time—something about Dale and "an unfortunate attachment—but of course, Cornelia, dear, she's so young—and I'm sure it will come to nothing now her father and I have made our attitude plain!"

"Pshaw—I bet that's it," thought Miss Cornelia shrewdly. "Dale's fallen in love, or thinks she has, with some decent young man without a penny or an 'eligibility' to his name—and now she's unhappy because her parents don't approve—or because she's trying to give him up and finds she can't. Well—" and Miss Cornelia's tight little gray curls trembled with the vehemence of her decision, "if the young thing ever comes to me for advice I'll give her a piece of my mind that will surprise her and scandalize Sally Van Gorder Ogden out of her seven senses. Sally thinks nobody's worth looking at if they didn't come over to America when our family did—she hasn't gumption enough to realize that if some people hadn't come over later, we'd all still be living on crullers and Dutch punch!"

She was just stretching out her hand to ring for Lizzie when a knock came at the door. She gathered her Paisley shawl more tightly about her shoulders. "Who is it—oh, it's only you, Lizzie," as a pleasant Irish face, crowned by an old-fashioned pompadour of graying hair, peeped in at the door. "Good morning, Lizzie—I was just going to ring for you. Has Miss Dale had breakfast—I know it's shamefully late."

"Good morning, Miss Neily," said Lizzie, "and a lovely morning it is, too—if that was all of it," she added somewhat tartly as she came into the room with a little silver tray whereupon the morning mail reposed.

We have not yet described Lizzie Allen—and she deserves description. A fixture in the Van Gorder household since her sixteenth year, she had long ere now attained the dignity of a Tradition. The slip of a colleen fresh from Kerry had grown old with her mistress, until the casual bond between mistress and servant had changed into something deeper; more in keeping with a better-mannered age than ours. One could not imagine Miss Cornelia without a Lizzie to grumble at and cherish—or Lizzie without a Miss Cornelia to baby and scold with the privileged frankness of such old family servitors. The two were at once a contrast and a complement. Fifty years of American ways had not shaken Lizzie's firm belief in banshees and leprechauns or tamed her wild Irish tongue; fifty years of Lizzie had not altered Miss Cornelia's attitude of fond exasperation with some of Lizzie's more startling eccentricities. Together they may have been, as one of the younger Van Gorder cousins had, irreverently put it, "a scream," but apart each would have felt lost without the other.

"Now what do you mean—if that were all of it, Lizzie?" queried Miss Cornelia sharply as she took her letters from the tray.

Lizzie's face assumed an expression of doleful reticence.

"It's not my place to speak," she said with a grim shake of her head, "but I saw my grandmother last night, God rest her—plain as life she was, the way she looked when they waked her—and if it was my doing we'd be leaving this house this hour!"

"Cheese-pudding for supper—of course you saw your grandmother!" said Miss Cornelia crisply, slitting open the first of her letters with a paper knife. "Nonsense, Lizzie, I'm not going to be scared away from an ideal country place because you happen to have a bad dream!"

"Was it a bad dream I saw on the stairs last night when the lights went out and I was looking for the candles?" said Lizzie heatedly. "Was it a bad dream that ran away from me and out the back door, as fast as Paddy's pig? No, Miss Neily, it was a man—Seven feet tall he was, and eyes that shone in the dark and—"

"Lizzie Allen!"

"Well, it's true for all that," insisted Lizzie stubbornly. "And why did the lights go out—tell me that, Miss Neily? They never go out in the city."

"Well, this isn't the city," said Miss Cornelia decisively. "It's the country, and very nice it is, and we're staying here all summer. I suppose I may be thankful," she went on ironically, "that it was only your grandmother you saw last night. It might have been the Bat—and then where would you be this morning?"

"I'd be stiff and stark with candles at me head and feet," said Lizzie gloomily. "Oh, Miss Neily, don't talk of that terrible creature, the Bat!" She came nearer to her mistress. "There's bats in this house, too—real bats," she whispered impressively. "I saw one yesterday in the trunk room—the creature! It flew in the window and nearly had the switch off me before I could get away!"

Miss Cornelia chuckled. "Of course there are bats," she said. "There are always bats in the country. They're perfectly harmless,—except to switches."

"And the Bat ye were talking of just then—he's harmless too, I suppose?" said Lizzie with mournful satire. "Oh, Miss Neily, Miss Neily—do let's go back to the city before he flies away with us all!"

"Nonsense, Lizzie," said Miss Cornelia again, but this time less firmly. Her face grew serious. "If I thought for an instant that there was any real possibility of our being in danger here—" she said slowly. "But—oh, look at the map, Lizzie! The Bat has been flying in this district—that's true enough—but he hasn't come within ten miles of us yet!"

"What's ten miles to the Bat?" the obdurate Lizzie sighed. "And what of the letter ye had when ye first moved in here? 'The Fleming house is unhealthy for strangers,' it said. Leave it while ye can."

"Some silly boy or some crank." Miss Cornelia's voice was firm. "I never pay any attention to anonymous letters."

"And there's a funny-lookin' letter this mornin', down at the bottom of the pile—" persisted Lizzie. "It looked like the other one. I'd half a mind to throw it away before you saw it!"

"Now, Lizzie, that's quite enough!" Miss Cornelia had the Van Gorder manner on now. "I don't care to discuss your ridiculous fears any further. Where is Miss Dale?"

Lizzie assumed an attitude of prim rebuff, "Miss Dale's gone into the city, ma'am."

"Gone into the city?"

"Yes, ma'am. She got a telephone call this morning, early—long distance it was. I don't know who it was called her."

"Lizzie! You didn't listen?"

"Of course not, Miss Neily." Lizzie's face was a study in injured virtue. "Miss Dale took the call in her own room and shut the door."

"And you were outside the door?"

"Where else would I be dustin' that time in the mornin'?" said Lizzie fiercely. "But it's yourself knows well enough the doors in this house is thick and not a sound goes past them."

"I should hope not," said Miss Cornelia rebukingly. "But—tell me, Lizzie, did Miss Dale seem—well—this morning?"

"That she did not," said Lizzie promptly. "When she came down to breakfast, after the call, she looked like a ghost. I made her the eggs she likes, too—but she wouldn't eat 'em."

"H'm," Miss Cornelia pondered. "I'm sorry if—well, Lizzie, we mustn't meddle in Miss Dale's affairs."

"No, ma'am."

"But—did she say when she would be back?"

"Yes, Miss Neily. On the two o'clock train. Oh, and I was almost forgettin'—she told me to tell you, particular—she said while he was in the city she'd be after engagin' the gardener you spoke of."

"The gardener? Oh, yes—I spoke to her about that the other night. The place is beginning to look run down—so many flowers to attend to. Well—that's very kind of Miss Dale."

"Yes, Miss Neily." Lizzie hesitated, obviously with some weighty news on her mind which she wished to impart. Finally she took the plunge. "I might have told Miss Dale she could have been lookin' for a cook as well—and a housemaid—" she muttered at last, "but they hadn't spoken to me then."

Miss Cornelia sat bolt upright in bed. "A cook—and a housemaid? But we have a cook and a housemaid, Lizzie! You don't mean to tell me—"

Lizzie nodded her head. "Yes'm. They're leaving. Both of 'em. Today."

"But good heav— Lizzie, why on earth didn't you tell me before?"