Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'Staggering and unforgettable storytelling' Mel Giedroyc In his retirement at the Vatican City, emeritus pope Benedict XVI is hard at work on his magnum opus: a high-school comedy screenplay. At a grimy pub in North London, a doctoral researcher is abducted by gangsters peddling William Wordsworth's handwritten account of drug-fuelled sex orgies. In the West African state of Benin, a politician's daughter inherits a large cash sum which she can only launder with the help of a random Englishman sourced on the internet. With twenty-one deliciously observed, gloriously mischievous short stories – some previously narrated on BBC Radio 4 or published in literary magazines, others completely new – Peter Bradshaw explores the boundary between the plausible and the absurd, often with a laugh-out-loud gag up his sleeve. Amid the playfulness, he has an enduring warmth and sympathy for every character, however hapless. He offers pinpricks of light in a dark sky of confusion and pain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PETER BRADSHAW is the author of three novels, Lucky Baby Jesus (1999), Dr Sweet And His Daughter (2003) and Night Of Triumph (2013), and regularly writes for radio and television. His selected reviews in The Films That Made Me (2019) represent his work at The Guardian, where he has been chief film critic since 1999. He lives in London with his wife, the research scientist Dr Caroline Hill, and their son.

Published in 2024

by Lightning Books

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

ISBN: 9781785633904

Copyright © Peter Bradshaw 2024

Reunion was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2016

Neighbours of Zero was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2017

All This Aggravation was originally published in Confingo Magazine in 2017

The Kiss was originally published in Confingo Magazine in 2018

Holiness was originally published in Esquire in 2018

My Pleasure was originally published in Confingo Magazine in 2019

Senior Moment was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2020

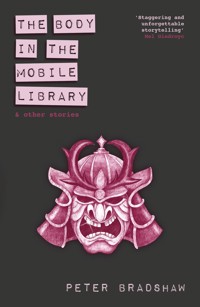

Cover design by Nell Wood

Illustration by Heather Heyworth

Typeset in Dante and Impact Label Reversed

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Sarah and Roy

Contents

The Kiss

Reunion

The Body in the Mobile Library

Senior Moment

The Bingo Wings of the Dove

Half-Conscious of the Joy

Holiness

All This Aggravation

Take Off

Appropriation

Neighbours of Zero

My Pleasure

Career Move

The Looking Glass

Ghosting

Fat Finger

Srsly

Palm to Palm

This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Intimate

Loyalty

Acknowledgements

The Kiss

To celebrate the election of Winston Churchill as Prime Minister in 1951, a former officer in the Polish air force called Tadeusz Andrzejewski bought a drink for a woman he’d only just met. This was in The Bell in Hendon, North West London. Elspeth Pierce was a seamstress at the Golders Green Hippodrome; she was a divorced woman in her early forties with a pretty smile. Tadeusz was still a virgin, despite having reached the age of twenty-five and seen dangerous action in the last war.

‘Ooh, may I have a ciggie?’ was how Elspeth had struck up the conversation.

‘Of course – but how did you know I smoked?’ Tadeusz had smilingly replied. He had not actually had a cigarette in his mouth, or any pack visible.

‘I just guessed.’

They had lit up, and after some explanation of his accent, Tadeusz asked if she had been up all night for the election. Elspeth replied that it had been a while since she had been up all night. Tadeusz agreed, but said that he had actually stayed up late because he was pleased for Mr Churchill. He had asked what she might like to drink. Elspeth asked for a Gin and It; Tadeusz got himself another pint of bitter, and they carried on talking.

‘So why are you not at work?’ Elspeth asked.

‘I’m a student,’ Tadeusz replied. ‘I’m studying philosophy at Queen Mary’s College.’

‘Are you indeed? And you’re in here, philosophising!’

‘Yes! Yes, I am.’

‘And what’s your philosophy, may I ask?’

Tadeusz, amazing himself with his forwardness, took Elspeth’s hand.

‘My philosophy is: seize the day.’

‘Gosh, mine too.’

They finished their drinks and Tadeusz bought the same again.

So what are you doing here in the afternoon, Elspeth?’ he asked, once they were settled again and talking about her job.

‘Well, there’s not much for me to do,’ she replied. ‘There’s no matinee today.’

She was working on a show called ForTheFunOfIt. They talked a little about that, and both silently noticed that the saloon was now entirely empty; they had a sort of privacy. Even the landlord was serving customers over in the public bar. This was not to say that another drinker might not come in at any moment.

‘I think you should be on the stage,’ said Tadeusz, extravagantly. ‘You’re much prettier than all those girls!’

‘Thank you darling!’ Elspeth exclaimed brightly, then leaned forward and kissed him on the lips.

The kiss continued. Elspeth’s tongue swarmed into Tadeusz’s mouth, and he set his glass back down on the table with a bang: it nearly spilt. They carried on kissing, and Tadeusz placed his hand on Elspeth’s right breast. She pushed his hand away but carried on with the kiss. Tadeusz now had a very painful erection. Finally, they broke apart and smiled shyly at each other. Hardly knowing what to do or say, Tadeusz fumblingly took out a ten-pound note and made to go up to the bar for more drinks, but Elspeth stopped him.

‘Don’t spend your money on drinks,’ she whispered to him. ‘Let’s go back to my flat. Brent Street. Do you know it?’

Tadeusz nodded quickly and emphatically, like a child.

Elspeth leaned in closer. ‘Do you have a French letter, Tadeusz?’ she murmured.

‘Back at my digs.’

‘Go and fetch it, darling, and meet me at 97B, Brent Street.’

They both rose, Tadeusz a little unsteadily, and parted at the door; he hurried downhill to his rooms in Stratford Road and Elspeth more calmly went up towards her place.

Tadeusz did indeed have a contraceptive at his lodgings, and could hardly believe that he was now about to put it to use. He walked more quickly.

As for Elspeth, she had a way of asking her new gentlemen friends for presents and was adept at timing the question. As Tadeusz was undressing in her bedroom, she would say something like: ‘Can I have that ten pounds, now, ducks?’ implying that they had already discussed the matter. The poor boy would be too embarrassed to make a fuss, too ashamed to admit that he had misunderstood the situation, too mortified to confess he genuinely thought he was so attractive as to sweep a woman off her feet at five minutes’ notice in the middle of the afternoon. He would hand over the money as meek as a lamb and they would go ahead. Elspeth could later, of course, with many forgiving endearments, tell Tadeusz she didn’t do this for just anyone, and that he was special.

Now trembling almost uncontrollably, Tadeusz arrived at his own front door and let himself in with his latch-key. He couldn’t help imagining Elspeth in her underclothes, and then in no clothes at all.

He kept his contraceptive hidden. It wasn’t in his rooms, where he knew his landlady would discover it, but in a concealed ledge by the steps in the building’s cellar, a gloomy, cavernous and frankly noisome space. It actually descended two levels below the ground, but the lower floor had been damaged by a bomb in the war. A brick staircase took you down eight steps and below that there was a void, a dark, empty and dusty vault. It was also very cold.

Tadeusz opened the door and pressed the light switch. Nothing. The bulb must have gone since he was last down here. He gingerly took two steps further and felt along the grimy brick levels to his right. Where was that contraceptive sheath? He couldn’t see. Angry and impatient, Tadeusz felt for his matches and, while both of his hands were thrust deep into his pockets, he stumbled and fell fifteen feet, head-first onto the stone surface below. He broke his neck, lost consciousness and died.

Tadeusz had made no noise, and the cellar door had swung closed behind him. Nobody had noticed him come in. He lay there, in the utter darkness, his feet pointing towards the front of the house, facing up, having effectively performed a twin-phase somersault on hitting the ground. The hours until teatime went by. Other tenants gathered in the dining room above for the evening meal and many people remarked on Tadeusz’s absence, particularly his landlady, Mrs Price. His rent, which he had paid three months in advance, was for half-board: bed, breakfast and evening meal, prepared in Mrs Price’s notoriously reeking kitchen. In Brent Street, Elspeth assumed that he had got cold feet and equably prepared for the evening’s work.

The days went by and Tadeusz’s disappearance became a subject of general conversation. A college official called at the house to ask if anyone knew of any reason why Mr Andrzejewski was persistently absenting himself from lectures and tutorials. Mrs Price telephoned the police and wrote to Lt Cmdr Richard Wilson, the RAF officer who had provided her with a reference for Tadeusz. Both were unable to help; the assumption was that he had simply gone home. Both his parents were dead and there were no relatives to notice his absence. Eventually Mrs Price re-let his room after confiscating and selling its contents: clothes, books. There was also an envelope containing fifty pounds in cash, which she quietly took and did not mention in her many shrill complaints about the situation.

Tadeusz’s rigor mortis relaxed. His face, quite invisibly in the cellar’s darkness, became ashy white as the blood settled on the underside of his body, but his arms and legs, again quite invisibly, turned an inky blue-black. His skin progressively dried out and shrivelled and made his hair and nails stand out the more starkly. His eyes, initially closed, half-opened in the dark as the eyelids contracted.

His lower intestine began to decompose, as micro-organisms broke down the dead cells. A greenish-brown patch began to spread across Tadeusz’s lower stomach, a sticky, damp mass of blisters, which stuck to and then ate through his vest and into his shirt, his trousers and his underpants. The putrefaction had begun. Bacteria spread through the body: the rotting advanced up his chest and down into his legs, and those two inert black flesh logs began to ooze and sweat decay. Presently, there was not a square inch of his clothing which was not saturated with degenerate matter. Internal gases pushed his intestines out through his rectum, and after two weeks, his stomach split along the fault line of a war wound with a report that was quite loud, but inaudible to anyone in the building.

The smell was not remarked upon by Mrs Price and her tenants, as the lower floors of her building were oppressed by the odours of her unclean kitchen, and the ventilation in the two icily cold basement levels was such that most of the odour was neutralised.

As the months went by, the decomposition continued in such a way that Tadeusz’s body mass diminished very considerably. Within a year, it was reduced and flattened, and a year after that it was hardly more than a dark, waxy outline upon the floor; the sticky, matted clothes gave it what substance it had. His skull was propped up at the top: a black cratered orb. The jaw became detached and rolled off Tadeusz’s right shoulder and onto the floor.

The years passed, the fifties became the sixties, and Tadeusz’s skeleton continued to thin down in the unvisited gloom. His bones, though ashier and more attenuated, continued to be an intelligible form. Mrs Price died in 1964 and her son, who wished in any case to emigrate to Australia, had no interest in managing a rooming house. And then the property, like everything else in the street, was subject to a compulsory purchase order, because the whole terrace was to be demolished to make way for three fifteen-storey blocks of flats.

The wrecking ball went through the buildings with an almighty crash and they collapsed heavily. Tons of masonry descended on Tadeusz’s remains and whatever unwitnessed form they had had for the previous fifteen years was, in a moment, utterly effaced. Some clearance was made and by the end of the decade the concrete foundations were being poured down into the vacant lot. The cement formed an undifferentiated mixture with the black atoms of Tadeusz’s residue, and above, the buildings climbed – three stark towers whose lift shafts and stairwells were always haunted by the howling of winds. As the seventies were succeeded by the eighties, Tadeusz’s molecules stayed constant in their cement animation, while the buildings became a notorious site for crime and drug dealing, but in the nineties the authorities discovered that this could be deterred simply by changing the open-plan design to make the premises secure. A front door would be added, with an entry code known only to vetted residents.

The twenty-first century dawned, with many of these flats sold off to their tenants or to other buyers: now they were desirable properties with excellent views over London and Middlesex. Their prices climbed, stalled a little with the crisis of 2008, and climbed again. But the dust got in from the pavement, and the sound of the wind was unceasing.

Reunion

In a quiet moment during a business trip, Elliot Chatwin reflected that he had been in love three times during his life. Once, while married and in his early forties, with Joan – a colleague. They were having an affair, although neither said that word out loud. Once before that, in his early thirties, with Michiko – who was now his ex-wife. And once when he was just eleven years old, with Lucy Venables, the girl who lived next door. She was also eleven.

Sitting on the bed in his hotel room, Elliot took a moment to consider the three affairs, and the three break-ups.

Easily the most painful was with Joan. He had scheduled one of their semi-regular dinner dates that often led to something back at her apartment. He had been a little bit early, sitting at a table, working up the courage to make some sort of declaration to her, trying to think what he might say, when Joan turned up and started saying, on sitting down, that she had fallen in love with somebody else, and they were moving in together. Elliot nodded his absolute and immediate acceptance of this situation. He even did a lip-biting little smile, taking it well, like a reality TV contestant getting told he’s not going through to the next round. Joan had said that, under the circumstances, it was probably better if they postponed dinner until some other time, having not in fact taken her coat off. She had never looked more beautiful, more strong and free.

With Michiko, it was in fact some time after that, in Tokyo, where they had gone for her mother’s funeral. After the ceremony, back at her family home, the couple had sat silently on a squashy black leather couch with disconcertingly ice-cold aluminium armrests. Michiko had asked quietly where he would be living when they returned to London. She looked stylish and slim: quite ten years younger.

And as for the last case? There had been no break-up as such, but his unrequited adoration for Lucy Venables had been just as real, just as painful, just as all-consuming as any of his other loves. He felt it was entirely correct to count it as one of the big affairs. In fact, he was inclined to think it was the grandest and most intense passion of the three.

Elliot smiled sadly to himself as he undressed in his hotel room, preparing to have a shower before attending that evening’s corporate cocktail party. What on earth had made him think of Lucy Venables after all this time?

Heaven knows, it was a disagreeable subject. Lucy Venables never loved him; she was wayward and capricious, and his last glimpse of Lucy was of her cruel little smile, looking on as her father gave him a slap across the face. In his adult life, Elliot had psychologically suppressed the memory of this, almost in its entirety.

Lucy Venables. Lucy Venables. Why was he thinking about Lucy Venables?

Subliminal images of her face, her house and her back garden had flashed into his mind that afternoon, after he had gone back into his room having attended a presentation at which all the other conference delegates were present. Like them, Elliot was involved in the solar panel industry. He had seen a sea of faces there. Could it conceivably be that a familiar set of features had been among them?

Elliot dismissed the idea with a smile and a tiny, audible laugh – a theatrical display of self-reproach for his own benefit. He showered, changed and turned up at the drinks reception which was being held in the hotel’s large and very dull function room, bordered on one side by a floor-to-ceiling glass wall with doors at either end. This looked out onto a landscaped garden which sloped down to an artificial lake. It was as manicured as a golf course. With every glance he took at this panorama, it had got darker, as night was falling and what he saw was the yellowish reflection of the room’s interior. Then this grassy expanse was suddenly re-illuminated by the electric lights positioned along the path that ran outside alongside the glass partition.

There was desultory conversation, not much helped by the name-tags that everyone was asked to wear; his read ‘Mr Chatwin’. Waiters circulated with drinks. The canapés were meagre. Elliot repeatedly allowed his glass to be refilled and as the evening wore on he felt quite drunk. He needed a cigarette. Smoking here was forbidden, of course. He wondered if he might smoke outside, on that large artificial lawn beyond the glass. This wasn’t at all certain. The no-smoking rules in hotels and public spaces extended outside in many areas nowadays. Elliot was just resolving to walk through the lobby area and out into the front car park – where he would surely be allowed to smoke – when suddenly he noticed something.

There was a woman, out there on the grass in the semi-darkness, smoking, with her back to him. Elliot had a strange feeling. Almost without knowing what he was doing, he absented himself from the party, walked out through one of the doors and headed across the Astroturf straight for her, with a half-formed idea about asking for a light.

Twenty paces away, Elliot paused, veering away, losing his nerve. He pretended to look out at the almost dark horizon, gazing in the same direction as the woman – and he made some play with getting out his cigarettes and tapping one against the pack. He sneaked a sidelong glance at her: a very attractive woman of about his age, smoking contemplatively, her right elbow in her left hand.

Was it…? Could it actually be…? There was nothing else for it. He would have to approach her.

‘Excuse me,’ he said. ‘I wonder if you….’

She turned to face him, and immediately gaped in dawning recognition. Her name tag read: ‘Ms Venables’. She was positively open-mouthed at the sight of him – and seeing his ‘Mr Chatwin’ she clapped the hand that wasn’t holding the cigarette over her mouth. Then she removed it and said: ‘Elliot! Oh my God! Oh my God! Is it you? Elliot!’

‘Hi, hello,’ said Elliot, hardly knowing what else to say.

‘Oh my God! Elliot! This is so weird! I was thinking about you this afternoon! Just now! So weird!’

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, I was thinking ab—’

‘Oh my God! So weird! I was thinking of that time in our back garden! With the darts! And Dad hitting you! Oh my God! And we never got a chance to talk to you or say sorry or anything!’

She was clearly drunker than he was. Elliott smiled self-deprecatingly, and made a gesture, as if to wave all these considerations away.

‘Do you remember me, Elliot?’ she then asked.

‘Of course,’ he replied.

‘And all that with my dad…and the darts… I’m so sorry! Gosh, do you know for years after that I used to think of you.’

‘Oh, I really don’t remember too much about it…’ Elliot said airily, with a smile.

This was quite untrue. Elliot remembered everything about it, and the whole history now came back into his mind, in every detail, with immense clarity and force. Lucy Venables’ family moved into the house next to his at the beginning of the baking summer of 1976. Elliot was an only child with few friends, and one endless hot day, he was riding his bicycle round and round on the flagstones of his front yard, where his dad’s car would be when he was not at work. He was seeing how tiny he could make the circle without falling off, and listening to his transistor radio playing Elton John and Kiki Dee singing ‘Don’t Go Breaking My Heart’. The sharp orchestral stabs and the repeated vocals used to go round and round in Elliot’s head:

Don’tgobreakingmy

Don’tgobreakingmy

Eventually, he toppled over – with a clumsy semi-dismount, jabbing his thigh on the saddle. He heard a giggle and turned to see Lucy staring at him.

‘You’re not very good at that, are you?’ she said pertly.

Elliot would at any other time have hotly insisted that he was, but now felt compelled to agree with this pretty stranger.

‘Why don’t you come next door, for some lemonade?’ she then asked, and Elliot said OK.

They went through Lucy’s front door, through the hall and into the kitchen.

Lucy poured out two glasses of Corona lemonade from a bottle taken from the fridge and they went out into the garden. There they mutely looked at Lucy’s swingball set for a moment, until Lucy’s mother appeared, with Lucy’s little sister.

‘Hello!’ she said brightly. ‘You must be Elliot. I had a nice chat with your mum yesterday, Elliot. We have to go now. Lovely that you’ve made friends with Lucy. Bye!’

Lucy and Elliot played swingball for a bit; Elliot’s reasonable skill in the game entirely deserted him and Lucy always won. They had some more lemonade and soon it was time for him to go.

Every day this scene would repeat itself. Without ever arranging it in advance, Elliot would hang around outside his house or on the pavement, and Lucy would come out and invite him in to play in her garden. They would play Robin Hood and Maid Marian, doctors and nurses, mummies and daddies. Silly baby stuff, considering that they were eleven-year-olds. But Lucy would always insist and Elliot could soon think of nothing else but pleasing her.

He fell in love with Lucy. There was just no other way to describe it. And it was made more poignant and intense for the lack of anything he could remotely recognise as sexual desire – merely a hot, sick feeling in his tummy. And when Lucy would start to make fun of him and be cross with him, as she always did, the feeling was even worse.

It all came to a head one Saturday afternoon, while Elliot was over at Lucy’s. Both her parents and her little sister were somewhere in the house. Sometimes the sister would wander out into the garden, to be sharply dismissed with a ‘Go away, Chloë!’ It was hot and Elliot was listless, and would not respond to her teasing and taunting. What was the matter, Lucy had asked. Elliot wouldn’t reply. She persisted, and finally he spoke up.

‘May I give you a kiss?’ he asked.

‘What?’ Lucy tried to sound derisive and mocking, but in truth she was taken aback.

‘I said: may I give you a kiss?’

Lucy was silent. As she pondered her reply – and as Elliot stared down at the ground, blushingly astonished at his own boldness – little Chloë came sauntering shyly out into the garden. Suddenly, Lucy said to her: ‘Come here!’

Obediently, she followed as Lucy led over to the garden shed, whose door had a dartboard and three darts. She plucked out the darts, opened out the door, stood Chloë up against it and, taking a box of coloured chalks from somewhere inside the shed, proceeded to draw a loose outline around the little girl’s head and shoulders, about twelve inches clear. Then Lucy offered the darts to Elliot.

‘There. If you can throw all three darts so they stick in the door, inside the line, but without hitting Chloë, then I’ll kiss you.’

Saucer-eyed, Chloë stayed perfectly still against the shed door, clutching her little doll, evidently content to be permitted to join her sister’s game on any basis.

‘OK,’ said Elliott numbly, taking the darts and positioning himself about seven feet away. He sized up his first throw, the dart-point lined up at eye-level, rocking back and forth on the balls of his feet – and then threw.

THUNK!

The dart landed just above the crown of little Chloë’s head.

‘Well done,’ said Lucy coolly. ‘One down; two to go.’

Elliot cleared his throat. After a few more little feints, he threw the second dart.

THUNK!

This one landed just to the left of Chloë’s neck, inside the line. It counted. But now the little girl’s lower lip was trembling; her eyes brimmed and she was starting to shift alarmingly about.

‘Stay still, Chloë!’ ordered Lucy. ‘All right, Elliot. Third and last dart. Get this right, and it’ll be a very big kiss for you.’

Elliot’s hand trembled. He seemed to lose his nerve just as he was sizing up the third throw. He exhaled heavily, the dart clenched in his fist down at his side. Then he raised it and prepared again. He threw. A clumsy one. The dart flew in the direction of Chloë’s left eye. She flinched, turned; it jabbed into the side of her ear. Chloë put her hand up to it; a trickle of blood ran down her forearm and for a moment it looked as if the dart was actually embedded in the side of her head.

Poor, panicky Elliot ran up and pulled away the dart. He thought he could actually hear the flesh of the little girl’s ear ripping. She screamed, and it was at this moment that Lucy’s father came running out into the garden. Elliot’s little victim ran up to him and hugged him around the waist, sobbing desperately. Her blood was getting on his trousers.

‘What the bloody hell’s going on here?’ he thundered.

‘Elliot was playing a sort of William Tell game daddy,’ said Lucy with a sweet smirk.

Her father coldly walked up to Elliot and smacked him once across the face – and then stood aside as Elliot blubberingly ran out through the kitchen and back to his house. Quite soon after that, Lucy’s family moved away and he never saw them again.

That is all that he could remember.

He was sure as he could be that this was what had happened. The woman now in front of him gave him a very familiar-looking smirk. That summer came rushing back, and with it the maddeningly catchy pop refrain in his head.

Don’tgobreakingmy

Don’tgobreakingmy

Elliot felt uncomfortable. He felt strangely intimate with this quasi-stranger, with whom the only thing he had in common was a bizarre episode decades before. And yet something in the situation’s unreality was liberating, even exciting.

‘Daddy used to talk about you a lot over supper,’ she said. ‘I think he knew he shouldn’t have hit you.’

‘Oh, I really can’t remember,’ he replied.

They were standing flirtatiously close.

‘I don’t think you ever got that kiss, did you?’ she said.

‘No,’ said Elliot, nullifying the effect of his previous claim. ‘Well, I wasn’t entitled to it.’

‘This party is very boring,’ she said.

‘Yes.’

‘Why don’t you come up to my room and I’ll give you a kiss now.’

She turned on her heel and went back through the now thinning party and into the foyer. Elliot followed.

They got into the lift, in which they were alone. They kissed.

Once at the sixth floor, they got out and headed for her room three doors along. Once inside, they kissed again, rolling on the big double-bed. Elliot began clawing her clothes off and, panting, she plucked at his belt.

‘Oh Elliot!’ the woman gasped. ‘Call me by my name. Say my name.’

She swept up her hair to reveal her cut and disfigured ear.

‘Call me Chloë.’

The Body In The Mobile Library

By the time DI Alex Greer and DI Jeff Wetherfield arrived at the crime scene, it was already taped off and the road closed. Uniforms crawling all over it. DI Wetherfield threw the half-filled Styrofoam cup of coffee he had with him into a bin; DI Greer dropped a lit cigarette on the pavement and twisted it out with his toe.

The scene itself, enclosed within the fluttering yellow ribbon, was actually a parked vehicle, the size of a lorry or two camper vans. Neither man knew quite what to make of it. The coachwork was a deep burgundy or brownish purple, with a kind of running board that swooped or curved at the rear of the vehicle into the entrance point, like a London Routemaster bus. It looked as if it had been designed some time during the Second World War.

DI Greer ducked under the tape which Wetherfield plucked up with his finger and thumb, and DI Wetherfield himself followed.

‘What is this thing?’ asked DI Greer of a white-clad forensic officer, carrying a clipboard, on his way out.

‘It’s a mobile library,’ said the man. ‘Buses full of books. Hertfordshire County Council sends them out to places where normal library facilities are inaccessible. It’s been coming here to Bricket Wood every other Thursday since 1974. Quite a dinosaur in the age of the internet. Ha!’ The officer gestured vaguely. ‘It usually parks up near the little parade of shops. But this morning they found it here. In the street.’

With a curt and uncomprehending nod, DI Greer dismissed the officer who walked off to his car, and the two men climbed into the library. They really did have to climb: the two steps were steep, and each had dozens of metal ridges, like an escalator. Inside was a corridor-type space, wide enough for two adults to pass each other with difficulty, in which one could walk up and down the length of the vehicle looking around at the high surrounding shelves crammed with books, although there were also CDs and old-fashioned videocassette boxes. A glass panel at the opposite end showed that the driver’s seat was empty, and it also cast weak daylight on the scene which now presented itself to the two officers.

The body of a middle-aged man, wearing a suit jacket and waistcoat, but no trousers or underpants, appeared slumped at the level of their feet, as if he had been sitting on the floor with his back against the wall of books, and then slid downwards. Around his bulging throat was a heavy belt buckled into a noose, the far end of which was attached through the farthest hole to some kind of hook or clip above his head near the shelf marked Historical Fiction. His eyes were open and staring, and his tongue was lolling out of his mouth. In his left hand was an empty half-bottle of white rum. His large penis was fully erect, apparently in a state between priapism and rigor mortis, and a slug-trace of dried semen was visible on the lower part of the waistcoat.

‘Oh my God,’ said DI Greer.

‘Yeah. Right,’ said DI Wetherfield.

‘No, I mean this guy. He’s Dickon, my sobriety buddy.’