Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

The books of the Minor Prophets resound with fierce condemnations of injustice and stunning examples of Yahweh's persistent mercy. Centuries-old prophecies come to pass, justice is served to corrupt leaders, and the oppressed are delivered. The book of Hosea presents an intimate allegory of God's love. The books of Joel, Amos, and Zephaniah proclaim the judgment and blessing of the coming day of Yahweh. The book of Jonah shows God's eagerness to forgive. The books of Obadiah, Micah, and Nahum vividly warn of Yahweh's wrath on economic exploitation and the enemies of his people. The book of Habakkuk discusses why evil sometimes prospers. The books of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi share prophecies of encouragement from when God's people rebuilt the temple and reclaimed hope after decades in exile. These twelve books balance justice and mercy, inspiring us to live uprightly as we await the universal spiritual renewal and righting of wrongs Yahweh will bring one day. I will keep watching for Yahweh to break through . . . and I know my God will hear my cry. Micah 7:7

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 595

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

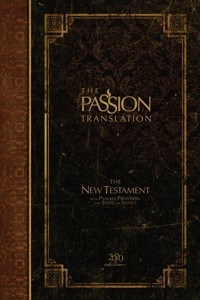

The Passion Translation®

The Minor Prophets: The Twelve

Published by BroadStreet Publishing® Group, LLC

BroadStreetPublishing.com

ThePassionTranslation.com

The Passion Translation is a registered trademark of Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc.

Copyright © 2024 Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except as noted below, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The text from The Minor Prophets: The Twelve may be quoted in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio), up to and inclusive of 500 verses or less, without written permission from the publisher, provided that the verses quoted do not amount to a complete chapter of the Bible, nor do verses quoted account for 25 percent or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted, and the verses are not being quoted in a commentary or other biblical reference work. When quoted, one of the following credit lines must appear on the copyright page of the work:

Scripture quotations marked TPT are from The Passion Translation®, The Minor Prophets: The Twelve. Copyright © 2024 by Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ThePassionTranslation.com.

All Scripture quotations are from The Passion Translation®, The Minor Prophets: The Twelve. Copyright © 2024 by Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ThePassionTranslation.com.

When quotations from The Passion Translation (TPT) are used in non-saleable media, such as church bulletins, sermons, newsletters, or projected in worship settings, a complete copyright notice is not required, but the initials TPT must appear at the end of each quotation.

Quotations in excess of these guidelines or other permission requests must be approved in writing by BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC. Please send requests through the contact form at ThePassionTranslation.com/permissions.

The publisher and TPT team have worked diligently and prayerfully to present this version of The Passion Translation Bible with excellence and accuracy. If you find a mistake in the Bible text or footnotes, please contact the publisher at [email protected].

9781424569915 (paperback)

9781424569922 (ebook)

Printed in China

24 25 26 27 28 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

A Note to Readers

Excursus on the Minor Prophets

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Postexilic Timeline

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

Your Personal Invitation to Follow Jesus

About the Translator

A NOTE TO READERS

It would be impossible to calculate how many lives have been changed forever by the power of the Bible, the living Word of God! My own life was transformed because I believed the message contained in Scripture about Jesus, the Savior.

To hold the Bible dear to your heart is the sacred obsession of every true follower of Jesus. Yet to go even further and truly understand the Bible is how we gain light and truth to live by. Did you catch the word understand? People everywhere say the same thing: “I want to understand God’s Word, not just read it.”

Thankfully, as English speakers, we have a plethora of Bible translations, commentaries, study guides, devotionals, churches, and Bible teachers to assist us. Our hearts crave to know God—not just to know about him, but to know him as intimately as we possibly can in this life. This is what makes Bible translations so valuable, because each one will hopefully lead us into new discoveries of God’s character. I believe God is committed to giving us truth in a package we can understand and apply, so I thank God for every translation of God’s Word that we have.

God’s Word does not change, but over time languages definitely do, thus the need for updated and revised translations of the Bible. Translations give us the words God spoke through his servants, but words can be poor containers for revelation because they leak! Meaning is influenced by culture, background, and many other details. Just imagine how differently the Hebrew authors of the Old Testament saw the world three thousand years ago from the way we see it today!

Even within one language and culture, meanings of words change from one generation to the next. For example, many contemporary Bible readers would be quite surprised to find that unicorns are mentioned nine times in the King James Version (KJV). Here’s one instance in Isaiah 34:7: “And the unicorns shall come down with them, and the bullocks with the bulls; and their land shall be soaked with blood, and their dust made fat with fatness.” This isn’t a result of poor translation, but rather an example of how our culture, language, and understanding of the world has shifted over the past few centuries. So, it is important that we have a modern English text of the Bible that releases revelation and truth into our hearts. The Passion Translation (TPT) is committed to bringing forth the potency of God’s Word in relevant, contemporary vocabulary that doesn’t distract from its meaning or distort it in any way. So many people have told us that they are falling in love with the Bible again as they read TPT.

We often hear the statement “I just want a word-for-word translation that doesn’t mess it up or insert a bias.” That’s a noble desire. But a word-for-word translation would be nearly unreadable. It is simply impossible to translate one Hebrew word into one English word. Hebrew is built from triliteral consonant roots. Biblical Hebrew had no vowels or punctuation. And Koine Greek, although wonderfully articulate, cannot always be conveyed in English by a word-for-word translation. For example, a literal word-for-word translation of the Greek in Matthew 1:18 would be something like this: “Of the but Jesus Christ the birth thus was. Being betrothed the mother of him, Mary, to Joseph, before or to come together them she was found in belly having from Spirit Holy.”

Even the KJV, which many believe to be a very literal translation, renders this verse: “Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.”

This comparison makes the KJV look like a paraphrase next to a strictly literal translation! To some degree, every Bible translator is forced to move words around in a sentence to convey with meaning the thought of the verse. There is no such thing as a truly literal translation of the Bible, for there is not an equivalent language that perfectly conveys the meaning of the biblical text. Is it really possible to have a highly accurate and highly readable English Bible? We certainly hope so! It is so important that God’s Word is living in our hearts, ringing in our ears, and burning in our souls. Transferring God’s revelation from Hebrew and Greek into English is an art, not merely a linguistic science. Thus, we need all the accurate translations we can find. If a verse or passage in one translation seems confusing, it is good to do a side-by-side comparison with another version.

It is difficult to say which translation is the “best.” “Best” is often in the eyes of the reader and is determined by how important differing factors are to different people. However, the “best” translation, in my thinking, is the one that makes the Word of God clear and accurate, no matter how many words it takes to express it.

That’s the aim of The Passion Translation: to bring God’s eternal truth into a highly readable heart-level expression that causes truth and love to jump out of the text and lodge inside our hearts. A desire to remain accurate to the text and a desire to communicate God’s heart of passion for his people are the two driving forces behind TPT. So for those new to Bible reading, we hope TPT will excite and illuminate. For scholars and Bible students, we hope TPT will bring the joys of new discoveries from the text and prompt deeper consideration of what God has spoken to his people. We all have so much more to learn and discover about God in his Holy Word!

You will notice at times we’ve italicized certain words or phrases. These portions are not in the original Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic manuscripts but are implied from the context. We’ve made these implications explicit for the sake of narrative clarity and to better convey the meaning of God’s Word. This is a common practice by mainstream translations.

We’ve also chosen to translate certain names in their original Hebrew or Greek forms to better convey their cultural meaning and significance. For instance, some translations of the Bible have substituted James for Jacob and Jude for Judah. Both Greek and Aramaic manuscripts leave these Hebrew names in their original forms. Therefore, this translation uses those cultural names.

The purpose of The Passion Translation is to reintroduce the passion and fire of the Bible to the English reader. It doesn’t merely convey the literal meaning of words. It expresses God’s passion for people and his world by translating the original life-changing message of God’s Word for modern readers.

We pray this version of God’s Word will kindle in you a burning desire to know the heart of God, while impacting the church for years to come.

Please visit ThePassionTranslation.com for more information.

Brian Simmons and the translation team

EXCURSUS ON THE MINOR PROPHETS

HISTORICAL DATING, CONTEXT, AND ORIGIN

The prophetic books that follow were originally contained in one book, which the Jewish people call “the Twelve.” According to the Talmud, the “men of the great assembly,” who lived during the Persian period, compiled the scroll of the Twelve.a In antiquity, scroll capacity was limited by practicality and size. Thus, each of the three Major Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel) fills up one unique scroll. The other twelve prophets were combined into one scroll. A more contemporary analogy is the music CD, which was designed to hold the totality of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony but can also be filled with many shorter musical numbers.

Broadly, the books cover the following themes:

•Three books of the Twelve cluster around the fall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel (722 BC): Hosea, Amos, Micah (as does the book of Isaiah).

•One book focuses on the fall of the Southern Kingdom of Judah (586 BCb): Zephaniah (as do the books of Jeremiah, Lamentations, and Ezekiel).

•Two books focus on the rebuilding of the temple: the prophecies of Haggai and Zechariah (520 BC).

•Six books have a less precise historical focus, and their dates are disputed in some cases: Joel (800s or 500s BC, among many other possibilities); Obadiah (800s or early 500s BC); Jonah (events occurred in the mid-700s but writing date is unknown; perhaps post-612 BC or later); Nahum (sometime in the second half of the 600s BC); Habakkuk (sometime between 612 and 586 BC); Malachi (sometime between 515 and 430 BC).

The prophets themselves demonstrated their genuine humanity in their respective books. And although we do not know everything about them—or, indeed, anything, in some cases—we know enough to be able to understand the main thrust of their messages. Precise dating and comprehensive biographical details may be helpful and interesting, but these are not essential for appreciating the primary emphases of their prophetic oracles and visions.

A great deal of emphasis was placed on the geographical centrality of Israel and Judah. None of the Twelve was born in captivity except, perhaps, Zechariah, who was most likely born in Babylon and then returned to Judah from captivity with the exiles around 538 BC.

In the Persian period (about 539 to 332 BC), Jerusalem had a population of fifteen hundred to four thousand, down from the prosperity of the late monarchy with twenty-five thousand inhabitants, complete with a king, his royal complex, and Solomon’s Temple.

After the great catastrophe of 586 BC, when the Babylonians laid waste to Jerusalem and the people were exiled, Judah had become a backwater client kingdom of a superpower. The people asked the question, What do we do about our powerlessness? The Twelve used memories of the past and visions of the future to put things into perspective and give people hope. Their message: “This is not the end of the road for Israel but rather a step in the journey toward a brighter future that will also bless the nations.” Such a message revealed their recognition of the central importance of the divine covenant in the history of the nations of Israel and Judah.

THE CENTRALITY OF THE DIVINE COVENANT

As we read through the prophecies in the Twelve, there is no doubt that the covenant undergirded their entire worldview. This covenant was one that encapsulated both the blessings and curses of that intimate divinehuman relationship between God and his people, and that divine grace and compassion were extended to the nations as well. This was the case even though in Obadiah and Nahum, the primary focus is on God’s judgment against wicked nations, and in Jonah, the focus is God’s compassion for a penitent gentile city. Nonetheless, in these three books, the covenant foundation is still there, even though it’s implicit rather than explicit. The following list notes covenant emphases in the Twelve:

Hosea. Israel was indicted for her “spiritual adultery” against Yahweh—that is, her idolatrous worship of pagan deities—and subsequently condemned to exile at the hands of the Assyrians: the curse of the covenant. But God then promised to restore his people to their homeland and renew them spiritually and materially: the blessing of the covenant. Joel. Israel was condemned for her self-indulgent lifestyle and suffered a catastrophic locust plague: the curse of the covenant, expressed here as a manifestation of the day of Yahweh. And again, God promised to heal the land and cleanse his people from their sin: the blessing of the covenant.

Amos. For her economic corruption and social injustices, Israel was condemned to exile at the hands of the Assyrians: the curse of the covenant. And then the Lord promised her restoration and spiritual renewal after her punishment: the blessing of the covenant.

Obadiah. The focus here is slightly different in that God cursed Edom for her brutal treatment of his people: an example of God applying the covenant curse to an enemy of his people. The curse declared that Edom would be destroyed but the kingdom of Israel would be blessed and prosper by the implicit covenant faithfulness of Yahweh.

Jonah. Unlike the other books among the Twelve, Jonah’s work is “a narrative account of a single prophetic mission”c and does not contain an oracle as such. However, it certainly demonstrates the compassionate love of God toward those who confess their sin and put their trust in him. This includes not only the people of Yahweh but also repentant gentiles, like this penitent generation of Ninevites. And, again, the NIV Study Bible notes, “This book depicts the larger scope of God’s purpose for Israel: that she might rediscover the truth of his concern for the whole creation and that she might better understand her own role in carrying out that concern.”d Readers can also note that such a concern has a distinctive covenantal foundation.

Micah. This book contains a series of alternating oracles of covenant curses and blessings. The prophet indicted Israel for her constant violations of the divine covenant statutes: injustice, corruption, cruelty, godless leadership, and the like. However, such judgment was accompanied by promises of forgiveness and renewal, including freedom from the oppression of her enemies.

Nahum. Similar to Obadiah, the book of Nahum focuses on the impending destruction of a wicked gentile nation, in this case, Assyria, via its capital city, Nineveh. It is again an example of the application of the covenant curse to a pagan nation. However, the blessings of the covenant were not forgotten here either, as God promised that the land of his people would never again be invaded by its enemies, for its enemies would be completely destroyed.

Habakkuk. This book is also unusual in the prophetic writings. It is an extended dialogue between the prophet Habakkuk and Yahweh, starting with the prophet feeling overwhelmed by the impression that God did not care about the rampant wickedness of the people of Judah. However, this conversation ultimately provoked a prayer of confession and praise from the prophet in which he recognized Yahweh’s faithfulness in delivering his people down through the ages and concluded with a determination to wait patiently for God’s redemptive purposes to be fulfilled. Again, the underlying framework for this interaction is clearly a covenantal one.

Zephaniah. The main theme of Zephaniah is the approaching day of Yahweh, signaling an outpouring of divine judgment (i.e., covenant curse) on both the pagan nations and Judah for their respective godlessness. And again, there is the concluding promise of Yahweh to bless his people and restore the fortunes of the Judean nation.

Haggai. In this postexilic prophetic book, Haggai proclaimed to his people that they were under the judgment of God because they had neglected the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem—a judgment with clear covenant undertones. As a result of the movement of the Spirit of God, the people responded in obedience, and God’s blessing was again poured out upon them when they resumed the rebuilding of the temple. That blessing was expressed both as a contemporary material prosperity and as a promise that anticipated a blessed Messianic future, when Yahweh declared that “the glory of this new temple will surpass the glory of the original” (Hag. 2:9).

Zechariah. This book contains a profound blend of prophetic visions along with judgment and salvation oracles, all undergirded by the foundation of covenant blessing and curse. In the end, the encouragement to the people of Yahweh is the dominant theme, expressed via these oracles declaring the future arrival of the long-awaited Messiah and his kingdom.

Malachi. After the people of Judah had returned to their homeland, the quality of their worship of Yahweh deteriorated to the point of rank corruption. The people further displayed their contempt for the covenant by widespread divorce in violation of their marriage vows, made worse by the practice of intermarriage with pagan women. All these abhorrent practices were understood as covenant violations deserving of divine punishment. However, Yahweh promised to send “the prophet Elijah” (Mal. 4:5) as a messenger to prepare his people for the coming day of Yahweh and to bring them to repentance—a promised blessing of the covenant.

To summarize, the causes of the slow spiritual decline of Israel, according to the prophets, may be expressed as twin failures of covenant obligation: corruption and disintegration.

•Corruption.Historian Lord Acton once said: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”e There is a constant call to more uprightness and justice throughout the Minor Prophets (and especially in the book of Amos). All the canonical prophets, both major and minor, commonly called out covenant violations involving injustices such as economic malpractice, corrupt business ethics, and oppression of the poor and vulnerable in Israelite society.

•Disintegration. This is the opposite of integrity. Israel had lost track of its primary focus: the covenant in the Torah. This was the organizing principle of society. When the people went after other gods, their loyalties became divergent, and society disintegrated. The primary cause of this disintegration, and, arguably, the Israelites’ most heinous sin according to the prophets, was indeed the worship of pagan deities. Idols totally distracted the people of God from their covenant fidelity and rotted their culture from within. This is as true for us today as it was for Israel in the times of the Twelve. Our obligation to love the Lord our God with all our hearts and minds has not disappeared, but our obligation has been refocused to serve and obey our risen Savior and Redeemer, the Lord Jesus Christ.

If we carry over the metaphor used in the preceding paragraph, we can see that the prophets point out “internal dry rot,” not external forces, as the primary cause of Israel’s downfall. There is a robust capacity for self-critique in the prophetic culture of ancient Israel, which brings conviction and the realization of guilt but also the opportunity for repentance and restoration. The message of the prophets: “The Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians did not do this to us, and outside alliances would not have saved us from them. We rotted, over time, from the inside, and this made us vulnerable. The essence of our problem has centered on the abandonment of our covenant with Yahweh.”

NONLINEAR LANGUAGE

Before proceeding any further, it will be helpful to offer some comments on a distinctive linguistic feature of biblical Hebrew, along with its concept of time and history, and how that linguistic approach informed the understanding of the covenant for the minor prophets and their original audiences.

A characteristic of the Hebrew language of the Old Testament is that it does not employ past, present, and future tenses in the same linear sense as English does. Semitic languages are not time oriented, but rather space oriented. A small rowboat can illustrate this spatial orientation well. The Hebrews saw the “future” as behind us as we row the boat of our lives “forward” with our backs to this future (which we cannot see or visualize). We row, facing the stern, by faith and not by sight. The “present” is right in front of our face: that with which we are dealing right now. The “past” is farther away from us but in front of us and receding into the distant past. The farther we row, the harder it is to see the past, and eventually it falls off the horizon and is forgotten. Thus, the prophets bring us out of our “nearsightedness” (just us and the boat) and vastly expand our worldview to explain how we got here and that which awaits us, “behind” us, as we row our boat into a promised future.

Another result of such a nonlinear approach is that a Hebrew understanding does not see cause and effect throughout history in the straightforward domino-effect understanding that English nudges its speakers toward. This has a bearing on the way ancient Hebrew prophets thought about the divine covenant: they were not locked into a rigid linear view of the past with consequences for the future that could never change or be changed. For example, in a linear view of history, whenever the Israelites disobeyed the statutes of the covenant, the consequences of that disobedience (i.e., God’s judgment) would be irrevocable and unchangeable. But this is not the view of the biblical prophets and writers. For them, the covenant, though originating in the past, was a dynamic nonlinear phenomenon that was and always would be ever-present and continually demanding of the people of God—past, present, and future. In other words, for the Twelve, the Israelite nation’s choices in relation to the covenant—choices made in the past and the present—have consequences for both the present and the future. Everything—whether blessing or judgment—depended on how they responded to the demands of the covenant at any given point in time.

The eminent Old Testament scholar Brevard Childs makes the following claim in relation to the progressively unfolding revelation of the divine plan of redemption in Scripture: “The Old Testament makes no sharp theological distinction between God’s intervention in human affairs within history or at the end of history. The issue at stake is the qualitatively new elements of the divine will at work.”f What he is referring to here is the manner in which God reveals and applies the divine covenant to his people at every stage of their history, past, present, and future. From Childs’ comments here, we may argue that there is a timeless quality to the prophetic portrayal of the promises of God to his people throughout their history. This is not to deny the reality or importance of a historical past for the Israelite nation. But rather, it beautifully emphasizes that the covenant promises of redemption throughout Scripture have relevance for both the contemporary audience of the prophet as well as future generations of readers and believers.

Let us take, for example, all the references in the Twelve—as well as those in the Major Prophets—t o the prophetic anticipation of Israel’s coming King, who will defeat all of Israel’s enemies and establish the universal kingdom of God that will endure forever. God revealed to his people progressively over many centuries the various elements that make up the prophetic picture of this victorious divine royal figure. All these elements then coalesced into a profound prophetic portrait of the Messianic King and came to fulfillment in the person of Jesus Christ, as revealed in the New Testament. But the process of this prophetic phenomenon is not a static one rooted in a single instance in the past, which is then projected forward to a single instance in the present and then to a single instance in the future with nothing in between.

Rather, the truth is that such a phenomenon is an ongoing dynamic process of covenant fulfillment that has its origin in early Israelite history and then moves on through the various stages of prophetic revelation, increasing in detail and complexity. It then finds its ultimate fulfillment in the emergence of Christ the King in the pages of the New Testament. Parallel to these promises and blessings are the progressive revelations of the covenant curse, again, recorded throughout the history of Israel in Holy Scripture and coming to a catastrophic conclusion in the final, eternal destruction of the enemies of God at the end of time.

When the reader bears the preceding comments in mind, the treatment of the divine covenant across the Twelve provides the following key takeaways:

•Yahweh alone rules the heavenly realm and all the kingdoms and empires of earth throughout the past, present, and future generations of the people of God. He sees all of time from his vantage point.

•These prophets opened a window in heaven, speaking forth Yahweh’s message and perspective. They showed how he is constant in his covenant love and justice from beginning to end (Mal. 3:6; see also Heb. 13:8) and yet has unique ways of dealing with his wayward children, depending on what is going on. Yahweh is not just the composer of the world but also the living conductor, dynamically engaged with us.

•These prophets thus spatially expanded the perspective of the original audience, who was hearing these messages during a low point in Israel’s history. The prophets gave the people an explanation for their predicament, putting their pain and disappointments and concerns into place within a larger plan—Yahweh’s plan. Knowing our place in God’s story, and that the story is not yet finished, has been a rock of hope for people in all places and all times. At the same time, the prophets showed the original audience—and us—a best-case scenario for the future, a vision worth striving for. They show us how to act in accordance with Yahweh’s vision and requirements for us.

•These prophets also vastly expand the worldview of their hearers or readers to better anticipate what awaits them in the future. The Lord’s words from the heavenly realm redirect his people’s eyes from what they can see to an eternal yet well-grounded hope that comes directly from him. From our vantage point in the New Testament era, we can see that many of the promises of the Minor Prophets (and the Old Testament as a whole) have been partially fulfilled with the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. But we still, along with the original audiences of the prophets, await the final climactic fulfillment of God’s promised plan of redemption: the return of Christ the King and the ushering in of his eternal kingdom, the new heavens and the new earth. We eagerly long for the perfect justice and perfect peace of his reign and the perfect relationship we will have with him and each other.

•This is what makes reading these books as valuable for us as it was for those during the nadir of Israel’s history, the Persian period. We all need our perspective expanded. These prophets expand our perspective of Yahweh’s sovereignty, his faithfulness, and his engagement with us and the world. They put our current situations, including whatever pain or complexity they encompass, into the perspective of the larger plan of God’s redemption, refocusing us on our ultimate hope in Christ and his past, future, and currently unfolding ultimate victory. These books were collected to affect, not just inform, the readers.

THE DAY OF YAHWEH: A DIVINE MERGING OF JUDGMENT AND BLESSING

The “day of Yahweh” (or “day of the Lord” in many translations) motif is, in fact, a subtheme of the covenant phenomenon, and anywhere it is mentioned in the Twelve there is an indisputable association with the covenant. This motif is characterized by the twin phenomena of blessing and judgment. While it is explicitly present in all the Minor Prophets—except for Jonah, Nahum, and Habakkuk, where its presence is implied—it occurs as a dominant theme in the books of Joel, Obadiah, Zephaniah, Zechariah, and Malachi. In every instance, the complexity of the day of Yahweh is evident, for the manifestations of divine blessings and judgments are applied to both the people of God and the nations. It is a day to be feared since God will pour out eternal judgments on those who scorned and rejected Yahweh and his covenant. It is also a day we should eagerly long for since we will fully realize all the promises of redemption and restoration from the totality of Scripture: Yahweh will pour out blessing on his people who heeded his covenant and establish his reign of perfect justice once and for all on the new heavens and the new earth.g

May the bones of the Twelve Prophets send forth new life from where they lie, for they comforted the people of Jacob and delivered them with confident hope.

—Sirach 49:10 (NRSVCE,h from the Apocrypha)

aLawrence H. Schiffman, Texts and Traditions: A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism (Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House, 1998), 118–19.

bNote that there is much debate surrounding many of the dates mentioned here and throughout the books of the Minor Prophets.

c“Introduction to Jonah,” NIV Study Bible, New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1985), 1364.

d“Introduction to Jonah.”

eCited in his letter to Archbishop Mandell Creighton, April 5, 1887. Retrieved on August 23, 2023, from history.hanover.edu.

fBrevard S. Childs, Old Testament Theology in a Canonical Context (London: SCM Press, 1985), 237.

gSome of the points for this Excursus were gathered from the Jewish Study Bible, 2nd Ed., (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 1125–30, which is a great source for further study on this topic.

hThis verse marked NRSVCE is taken from New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition. Copyright 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

HOSEA

(return to table of contents)

Introduction • One • Two • Three • Four • Five • Six • Seven • Eight • Nine • Ten • Eleven • Twelve • Thirteen • Fourteen

HOSEA

Introduction

AT A GLANCE

Author: Hosea the prophet

Audience: Originally, the Northern Kingdom of Israel; later the Southern Kingdom; today, people of God everywhere

Date: The era preceding the fall of Samaria (capital of the Northern Kingdom) in 722 BC

Type of Literature: Prophecy

Major Themes: The covenant: violation and renewal; love; corruption; disintegration through spiritual adultery; hope; Jesus as the faithful husband

Outline:

I.

Superscription: author and setting — 1:1

II.

Hosea’s marriage and its symbolism: unfaithful wife, faithful husband — 1:2–3:5

a.Hosea’s marriage; birth of children (unknown fathers); readoption into the family of God—1:2–2:1

b.Allegory of Gomer, the unfaithful wife — 2:2–23

i.

Inevitable divine judgment on Israel — 2:2–13

ii.

Promised divine renewal and restoration of Israel — 2:14–23

c.Hosea’s reconciliation with his wife — 3:1–5

III.

Faithless nation and faithful God — 4:1–14:9

a.Summary of charges (the rib):Yahweh’s legal indictment of Israel’s covenant violations — 4:1–3

b.Charges laid and sentencing brought down — 4:4–10:15

i.

Punishment of priests and people for their idolatry — 4:4–19

ii.

Punishment of priests, Israelites, and royal leaders for their violence, injustice, and corruption — 5:1–15

iii.

A counterfeit repentance — 6:1–3

iv.

Indictments of Israel for their covenantbreaking — 6:4–7:16

v.

Punishment of Israel for their covenantbreaking —8:1–10:15

c.Yahweh’s faithful love — 11:1–14:9

i.

Yahweh’s fatherly love — 11:1–11

ii.

Punishment for the people’s covenantal unfaithfulness — 11:12–13:16

iii.

Israel’s promised restoration and renewal following their genuine repentance — 14:1–9

ABOUT THE BOOK OF HOSEA

For more information on the twelve books of the Minor Prophets in general, please see the excursus on the Twelve preceding this book.

Hosea is a very personal account of the life and ministry of the titular prophet. God told Hosea to marry a woman who would be unfaithful to him. They had three children (and Hosea may not have been their father) who were named by God and represented prophetic messages not only for Hosea but also for Israel and for us today.

Hosea’s ministry was contemporary with the reigns of the following kings (note that some of these reigns overlapped, incorporating coregencies): in Israel, Jeroboam II, 793–753 BC; in Judah, Uzziah (Azariah), 792–740 BC; Jotham, 742–735 BC; Ahaz, 735–715 BC; Hezekiah, 715–687 BC.

One of the older books in the Bible, Hosea perhaps reached its final form even before many of the scrolls of the Hebrew Bible were compiled and put in order, certainly before many of the other prophets even lived. Many of the verses may reflect older Hebrew usage and are hard to translate. There’s a similar situation in the New Testament: the letter of Paul to the Galatians was likely in its final form before the Gospels were compiled and put in order even though the Gospels narrate earlier activity.

Hosea frequently called out Israel using the metonymy Ephraim. Ephraim was one of the tribes of Joseph and the most powerful of the Northern Tribes. This is parallel to calling the Southern Kingdom “Judah.” Over the centuries, Ephraim (with its capital, Samaria) and Judah (with its capital, Jerusalem) had emerged as the primary tribes from among the twelve, and the Northern and Southern Kingdoms, as a whole, were often called by the names of these two tribes.

PURPOSE

Over history, the book of Hosea has functioned with at least three purposes.

Initial purpose: The Northern Kingdom of Israel, although very prosperous, had big spiritual and ethical cracks in its foundation, brought about fundamentally by her violation of the terms of the divine covenant (Hos. 4:1–19; 6:7; 8:1). The book is dominated by the threats of inevitable divine judgments against the people of Yahweh for their covenant rebellion against him. However, notwithstanding the predominance of these threats, Yahweh, out of love for them, issued through the prophet promises along with warnings: If they repented of their faithlessness and returned to their God, he would renew and restore them in their intimate covenant relationship with him. On the other hand, if they continued in their rebellious ways, destruction at the hands of the Assyrians would be inevitable.

Second purpose: By the time this book was put in its final form and added to the scroll of the Twelve, there were few survivors, if any, from the Northern Kingdom to read it; we have never heard of the “ten lost tribes” again. The action in Hosea is set in the season of decline before the fall of the Northern Kingdom (722 BC) but was added to the scroll of the Twelve to benefit the survivors of the fall of the Southern Kingdom (much later, in 586 BC) by helping them avoid the same mistakes the Northern Kingdom had made. One can picture a parent saying, “Don’t make the same mistakes your big brother made!” (see 4:15).

In much the same way, this book served as essential, practical wisdom during the years of restoring and rebuilding Jerusalem allowed under the Persians.

Third purpose: As readers today, we all, individually and collectively, as communities and nations, face the same kinds of challenges that the Northern Kingdom of Israel faced. As we grow in prosperity, the temptations of corruption and arrogant selfishness can begin to look more attractive, and we start to believe we have the power to pull it off. Also, when we look to human leaders (“kings” in the book of Hosea; 5:13; 7:7; 8:4; 10:3–4, 7; 13:10–11) rather than the Lord for solutions, we start to go astray. When an individual or a society loses focus of the Creator who brought us into the world and who has a plan for our lives, things start to unravel. Hosea warns, and it is still true, that these tendencies can lead to a point of no return. However, the book ends with a call to return from these false paths to the promises of God and his love for us. This message is still vitally relevant for us today: we need to continue to do this on a regular basis, being eternally grateful for the enactment of the new covenant age via the person of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Never again need we fear the curses of the old covenant—as Hosea’s audience did—because Jesus has borne them on our behalf.

AUTHOR AND AUDIENCE

Hosea of Beeri wrote the book bearing his name. Hosea’s name means “He [Yahweh] has saved”; it is a variant of the name Joshua, which is the English name for Jesus (Num. 13:16).

Hosea was most likely from the Northern Kingdom of Israel. He was a contemporary of the prophet Isaiah in the Southern Kingdom of Judah. Amos also lived during this generation.

Like Jeremiah, Hosea was a man of deep feelings, including anguish over the sins of his people. He had a fearless spirit and demonstrated selflessness in his dealings with others. The message burned inside his heart, and he knew he must be faithful to bring that message to his nation. He was intensely human, filled with emotion.

Jewish tradition has his burial site in Tsfat, Israel (Galilee). Unlike some of the other prophets, he is not mentioned elsewhere in Scripture.

The original audience of Hosea’s message was the people of the Northern Kingdom in the times before the fall of Samaria. Hosea called them Israel, Jacob, Ephraim, and Samaria in this book. Destruction by the Assyrians loomed over them, and Hosea warned the people, hoping that they might avoid this catastrophe.

The secondary audience was the people of Judah (the Southern Kingdom) much later on, who were in captivity in Babylon and Persia (like Daniel and Esther) or rebuilding Jerusalem (like Ezra and Nehemiah). Eventually, as one of the parts of the scroll of the Twelve, Hosea’s words were repurposed during the Persian Era as a calling out to the faithful remnant of the Southern Kingdom (Judah) that they might live into God’s preferred future for them and avoid the mistakes of the Northern Kingdom, which had, by that time, disappeared as a nation.

The third audience is the contemporary reader. We face the same truths, challenges, promises from God, and options that the Northern Kingdom did.

MAJOR THEMES

The Covenant: Violation and Renewal. This theme pervades the entire book. The opening three chapters describe the living metaphor of Hosea’s marriage, by Yahweh’s command, to Gomer, an “adulterous woman” (1:2), who would be guilty of infidelity on a number of occasions. She bore him three children—whom the prophet may or may not have fathered—and they were all given names that symbolized the judgment of God against his people: Jezreel, No-Tender-Mercy, and Not-My-People (1:2–2:1). It is abundantly clear that Gomer symbolized the faithless people of Israel (and Judah), with Yahweh as the “betrayed husband.” Israel’s underlying infidelity was a spiritual one, namely, her abandonment of Yahweh as her unique covenant God—worshiping pagan idols in his stead.

Like Gomer, Israel would bear the painful consequences of rebellion and faithlessness: Gomer would suffer for her marital infidelity, violating her marriage covenant (2:2–13), and Israel likewise, for violating the divinely revealed covenant—i n particular, the first commandment to worship Yahweh exclusively (beginning with ch. 4). However, God commanded Hosea to take his adulterous wife back—t o rebetroth her, if you like (3:1–5), just as Yahweh promised to rebetroth his people, renewing his covenant relationship with them (2:14–23; 11:8–11; 14:1–9). The application of this living metaphor to Yahweh’s relationship with Israel occupies the remainder of the book (chs. 4–14). And this promise of covenant renewal finds its ultimate fulfillment in the person and work of Jesus Christ. All the topics listed and discussed below are submotifs of this principal theme.

Love. The theme of love is a significant one in the book of Hosea. However, the issue is complex, for the term love is used in polar opposite contexts—irom Yahweh’s amazing covenant love (Hb. chesed; see below) to the idolatrous, immoral, and illegitimate love of self, as demonstrated by the wayward Israelites. There are three different words (including two couplets—a verb and a noun) for “love” employed by the prophet, and together they amount to nearly thirty occurrences. Each term reflects varying semantic elements.

The most theologically profound of these terms is the Hebrew word chesed. The word occurs four times in this book. It denotes the pure, selfless love of Yahweh, expressed in the administration of the covenant, and is often translated “loving-kindness” throughout the Old Testament. As an attribute of Yahweh,chesed is used once, in 2:19, where God promised to betroth himself anew to Israel in his everlasting “love.” The other three uses of the term are found in varying contexts: In 6:4, God indicted Israel for her shallow “faithfulness” for him that dissipates like the morning mist. In 4:1, God similarly indicted his people for their total absence of “love” toward him. And finally, in 12:6, God demanded that his people return to him (i.e., in repentance), maintaining “love” and justice in all their dealings with one another.

Secondly, the words racham/ruchamah denote the action of “loving tenderly” and the quality of “tender love.” They are found eight times in the book, and the prophet used them both positively and negatively. The most significant negative usage occurs in the opening two chapters, where God named one of Gomer’s children—a daughter—No-Tender-Mercy (1:6; 2:23). But then the term is used positively, when God promised to rename the child Shown-Tender-Mercy at the time of Israel’s promised renewal and restoration (2:1, 23).

The third set of words, ‘ahab/‘ahabah, denotes love that is both human and divine. These words occur seventeen times in the book, describing the action and quality of love of both God and the people of Israel. Some contexts are positive, where the love of God is affirmed (e.g., 11:1, 4), and others are negative, where the love demonstrated by the Israelites is corrupted, idolatrous, or self-centered (e.g., 4:18; 9:1).

Corruption. The Northern Kingdom (Israel) had grown prosperous. Human beings tend to form hierarchies, and those at the top of the ladder are often tempted to feather their nests and protect their positions, hanging on to power. A poor person can be dishonest but does not always have the power to exercise corruption, which is an abuse of power (much like the fact that a stranger cannot betray you; only a friend can do that). English historian and philosopher Lord Acton famously said: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”a In asking for a hierarchical system—demanding a king in 1 Samuel 8:1–11—Israel had paved the path to potential corruption, which started with Solomon and seemed to get worse over time. The prophets, like Hosea, decried the absence of the traditional Hebrew virtues of justice and uprightness in the face of this corruption (Hos. 5:1, 3, 10–11; 6:10; 7:1; 9:9; 10:4; 12:6, 8). Corruption, like disintegration (see below), is not sustainable, and a society filled with corruption will crumble from the inside.

Disintegration through Spiritual Adultery. Hosea emphasized the sin of idolatry and illustrated Israel’s spiritual adultery in her relationship with God by his own marriage to an unfaithful woman. Hosea’s own reconciliaiion also illustrates Israel’s ultimate promised restoration (1:1–3:5).

Disintegration is the opposite of integrity. When one is integrated, he or she is not double-minded or conflicted on the inside. The first commandment, to have no other gods before God, is a call to individuals and communities to live an integrated life and to avoid those things (symbolized and illustrated by idols in the Bible) that create disintegration within us. Disintegration is spiritually fatal. We can be forgiven for it, but unless we address it seriously, it can rip our lives to shreds (13:5–8), and collectively, it can bring down an entire civilization. For Israel, an integrated existence consisted of keeping the first commandment, avoiding idols, and living in accordance with the covenant—an existence that Israel failed to maintain (3:1; 4:7, 10–19; 6:10; 8:4–6; 9:1, 10; 10:5–6; 11:2; 13:2).

Other sins that Hosea mentioned include injustice (12:7), violence (4:2; 6:9; 12:1), hypocrisy (6:6), rebellion (7:3–7), forming alliances with foreign nations (7:11; 8:9), arrogance (13:6), and ingratitude (7:15). Again, we can note that all these sins constitute a subset of the primary transgression of violating the covenant.

Hope. While the theme of hope is scattered throughout the book (1:10–2:1, 14–23; 3:5; 5:15; 11:8–11), Hosea ends on a particularly expanded note of hope (14:2–9). God’s promises to his people in the Northern Kingdom were laid out in front of them (14:2–9)—free for the taking. Alas, they rejected these promises at the time, and the dry rot of corruption and disintegration became fullblown. The capital, Samaria, fell in 722 BC, never to be restored. Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that this hope of restoration and renewal turned out to be a historical certainty. Notwithstanding Israel’s failure to live up to God’s demands, Israel’s deliverance from captivity and subsequent spiritual renewal, did, in fact, take place with the people’s return to their homeland in 538 BC. And this hope continues to call out to anyone who will listen, down through the ages unto this very moment—a hope that is grounded in the fulfillment of God’s plan of redemption, fully realized in the coming of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Messiah and Lord, to this earth. Eternal renewal and restoration are found only by trusting in his atoning sacrifice for our sins.

Jesus as the Faithful Husband. This theme has been anticipated in the previous discussions on the violation and renewal of the covenant and the preceding thematic summary of hope. The prophet Hosea, who loved the unfaithful woman, showed a foretaste of the faithful love of Jesus. Through the eyes of faith, we see Hosea’s marriage to Gomer as a parallel to Jesus and the church (Eph. 5:25–32). He still loves her despite her sin (Rom. 5:8) and sacrificially bought her back.

Jesus is visible in the book of Hosea in the following additional ways:

The name Hosea, which means “He has saved” (Matt. 1:21)

The “one head” (or leader) who reunites his people (Hos. 1:11; Eph. 2:11–22; Col. 1:18–20)

The son called from Egypt (Hos. 11:1; Matt. 2:14–15)

The “David-l ike king” (Hos. 3:5; Matt. 1:1; Rom. 1:3; Rev. 19:16)

aCited in his letter to Archbishop Mandell Creighton, April 5, 1887. Retrieved on August 23, 2023, from history.hanover.edu.

HOSEA

Amazing Love

1Here is Yahweh’s message that came through the prophet Hosea son of Beeri.a At that time, Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah ruled as kings of Judah, and Jeroboam the son of Joash was king in Israel. 2This is the beginning of what Yahweh spoke through Hosea.

Hosea’s Marriage

Yahweh said to me, “Go and marry an adulterous womanb and have children of adulteryc because the people of the land are adulterers. They have forsaken me.” 3So I married a woman named Gomer,d Diblaim’s daughter. She became pregnant and bore a son.

4Yahweh said to me, “Name him Jezreele because it will not be long before I punish the dynasty of Jehu for the massacre at Jezreel and then destroy the kingdom of Israel. 5At that time, I will smash Israel’s military powerf in the Valley of Jezreel.”g

6Later, Gomer became pregnant again and gave birth to a daughter.hYahweh said to me: “Name her No-TenderMercyi because I will no longer have tender mercy on the nation of Israel. I will certainly not forgive them. 7I will, however, have compassion on the nation of Judah.

“I will rescue them! I will not give them victory through their weapons and military might.j It will not be their horsemen and chariots that deliver them. I, Yahweh their God, will save them!”

8After Gomer weaned her daughter, No-Tender-Mercy, she became pregnant again and gave birth to a son.k9Then Yahweh said to me, “Name him Not-My-Peoplel because you, Israel, are not mine anymore, and I am not yours.”m

Israel’s Restoration

10Yet someday,n the number of the people of Israel will become as innumerable as the sand of the sea, which cannot be counted.o AlthoughpGod named them Not-MyPeople, he will restore them and call them Children of the Living God.q

11The divided people of Judah and Israel will reunite. They will appoint themselves one headr and will once again cover the land like grass that sprouts from the ground. How great will be the day when the meaning of Jezreel’s name is fulfilled: God sows!

a1:1 Beeri means “my wellspring.” Jewish tradition states that Beeri was a prophet who was a wellspring of revelation and greatly influenced Isaiah.

b1:2 Or “Go marry a woman of harlotries.” It is possible that Hosea was told to marry a temple prostitute from the fertility cult of Baal. However, some view this description as a prediction—that is, that she was not necessarily a prostitute when Hosea married her but would prove to be unfaithful to him in the future. Gomer is nowhere called by the Hebrew word zonah (“prostitute”). Commentators and translators are varied in their explanations and translations of the Hebrew.

c1:2 Or “she will have children born through unfaithfulness [adultery].” Throughout the Old Testament, prostitution is a symbol of Israel’s unfaithfulness to God and of pursuing false gods (idolatry). See Jer. 2–3; Ezek. 16; 23.

d1:3 Gomer means “all finish with her” or “ending.”

e1:4 Jezreel means “God sows” or “may God sow.” However, Jezreel was best known as a place, the location where Jehu assassinated Israel’s King Ahab and his family (see 2 Kings 9–10).

f1:5 Or “bow,” a metonymy for military power.

g1:5 The Valley of Jezreel runs eastward from the capital city of Jezreel near Mount Gilboa toward the Jordan River. The Valley of Jezreel was the location where invaders from the north entered the land (see Judg. 6:33) and a frequent site of large battles in history. The valley was flat and navigable for chariots (as opposed to the Judean highlands). Many such clashes took place here, generally initiated by the superpowers Egypt and Mesopotamia trying to extend their reach into the lands between them (such as Israel). The prophecy of this verse was fulfilled when the Assyrians invaded and defeated Israel.

h1:6 It is entirely possible that Hosea was not the father of this child.

i1:6 The Hebrew root word is racham, a word of tender love, like motherly love for a child. It has a homonym that means “womb.” Perhaps “womb-l ove” could be a possible translation for the word translated here as “tender mercy.”

j1:7 Or “through their warrior’s bow, sword, and warfare.”

k1:8 It is entirely possible that Hosea was not the father of this child.

l1:9 To paraphrase this in language that shows the emotional power of the prophet’s mandate, we could describe Hosea’s family as follows: “He is married to a harlot, has one kid named after a disaster [Jezreel] and two others called, essentially, ‘Unloved’ and ‘Unwanted’ “ (Joel Hoffman, And God Said: How Translations Conceal the Bible’s Original Meaning [New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010], 226).

m1:9 Or literally “I [am] not I AM for you” (cf. Ex. 3:14) or “I do not exist for you.” A solemn statement indeed! This serves as a decree of divorce. God canceled the covenant relationship between himself and Israel.

n1:10 In the Hebrew Bible, this paragraph is the first part of ch. 2. Most English translations keep this paragraph as part of ch. 1.

o1:10 Even when God sends judgment, mercy will prevail. He will restore and renew and reveal his love again. See Hab. 3:2.

p1:10 Or “In the place where,” which could be a reference to Jezreel.

q1:10 We must always remember that mercy triumphs over judgment. God always remembers to show mercy (see Isa. 54:8).

r1:11 Jesus is the “one head” over all his scattered people. He has reunited Jew and gentile into one new person (see Eph. 2:15). We are the seeds he has sown into the earth (see Matt. 13:1–23, 38), and he is the Head of the church (see Col. 1:18).

Yahweh’s Unfaithful Wife

2 “Call your brothers My-People and your sisters

Shown-Tender-Mercy.

2Go to court. Take legal action against your mothera

and put her on trial.

For she is no longer my wife,

and I am no longer her husband.b

She must remove the symbolsc of prostitution from her face

and the seductive charms of her adulteries from between her breasts.

3If not, I will strip her naked and humiliate her

and expose her nakedness as on the day she was born.d

I will make her as bare as the desert,

turn her into a barren land,

and let her die of thirst.e

4I will feel no pity for her children,

since they are the children of her shameless prostitution.

5Yes, their mother has prostituted herself,

the one who conceived them has disgraced herself.

For she said, ‘I will chase after my lovers;f

they will provide all I need:

my robe, my clothing,g my oil, and my wine.’

6Behold! I will block her way with thorns

and build up a wall against her to stop her in her tracks.

7Then when she tries to chase her lovers,

she will not be able to catch them.

When she looks for them, she will not find them.

Eventually, she’ll say, ‘I must go back to my own husband.h

I was much better off then than I am now!’i

8Yet, she never understood

that I was the one who was giving her

the grain, sweet wine, and olive oil.j

I lavished upon her an abundance of silver and gold,

which shek took and made into idols of Baal.

9So I will take back my grain at harvest time

and my new wine when the grapes are ripe.

I will snatch away my wool and my flax

used for clothing to cover her naked body.

10Then very soon I will publicly expose her disgrace

before her lovers’ gawking eyesl—

so that no man will steal her from me.

11I will put an end to all her joyful festivities,

her feasts, her new moons and her Sabbaths,

and her celebrations will all cease.

12I will ruin her vines and fig trees

of which she used to say,

‘These are the fees that my lovers pay to me.’

I will turn vines and fig trees into a jungle

and make their fruit nothing but food for wild beasts.

13I will make her pay for the feast days,

feasts for her to burn incense to the Baals.

She got all dressed up and chased after her lovers,

adorned with earrings and necklaces for them.

And me? She has forgotten about me.

This is Yahweh speaking to you!”

God’s Amazing Love for His People

14“Behold, I am going to romancem her

and draw her into the wilderness;n

I will speako tenderly to her there with words of love

and win her heart back to me.

15There I will give her back her vineyards,p

and make the Valley of Troubleq an open door to hope.r

There she will respond to me and sings as when she was young,

as on the day when she came up from Egypt.

16“And I, Yahweh, declare that when that day comes,

you will call me ‘My Husband’

and no longer call me ‘My Master.’t

17I will banish the names of the Baals from her lips,

and she will never mention their names again.

18When that day comes, I will make a covenant for you, my people,

with all the birds and wild animals

and creatures that creep upon the ground.u

I will break the bow and the sword

and remove the weapons of war from the land,

and I will let you live in peace and safety.

19I will take you to myself as my wife forever.

I will make you mine in righteousness and justice,

with unfailing love and tender affection.

20Yes, I will commit myself to you in faithfulness.v

Then you will know me intimately as Yahweh.

21When that day comes, I will be the God who responds,”w

declares Yahweh.

“I will respond to the heavens,

and the heavens will respond to the earth,

22and the earth will respond to the grain, the wine, and the olive oil,

and they will respond to Israel.x

23I will sow her in the land as my very own.

I will show my tender mercy to No-Tender-Mercy.

I will declare to Not-My-People my words of endearment:

‘You are my people,’

and they will say to me, ‘You are my One-and-Only God.’ “

a2:2 Or “Plead with your mother” or “Accuse [indict] your mother.” The Hebrew word for “plead” is rib or riyb and is frequently used for filing a legal complaint and is associated with taking someone to court. Implied in the text is that Yahweh was taking Israel to court but her children (the remnant of Israel) must file a complaint for the court case.

b2:2 This statement is usually seen as a formal divorce decree. The covenant between Yahweh and Israel had been broken by Israel’s unfaithfulness.

c2:2 This is likely a reference to cosmetics, jewelry, or symbols on her forehead that would identify her as a prostitute.

d2:3 See Ezek. 16:39.

e2:3 A thriving nation is rich in children. But in this prophecy, Israel would become depopulated and less fruitful. The commandment to be fruitful and multiply (God’s first command and one he repeated many times) involves both productivity and procreation. Hosea was evoking both here.

f2:5 In this allegory, Israel’s lovers would be the pagan gods she worshiped and alliances with Egypt, Syria, or Mesopotamia (whoever happened to be in charge there, the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, or Greeks).

g2:5 Or “my wool, my flax.” Robes were often made of wool, and flax is used to make linen clothing.

h2:7 Or “to my man, the first.”

i2:7 Israel may have chased other gods, but there is only One who loved her: Yahweh. Gomer may have had many lovers, but Hosea was the first who genuinely loved her. Jesus first loved us, and that’s why we love him. For the believer, it is futile to chase after anyone other than Jesus. For you will discover in the end that you were better off with Jesus alone.

j2:8 The irony is clear. The “fertility” gods she chased after couldn’t provide her with what she needed. God was providing for her even as she wandered from him.

k2:8 Or “they.”

l2:10 People try to hide sexual immorality because conscience tells us it is shameful. The proper punishment is to expose it.

m2:14 Or “allure” or “seduce.” The Hebrew word patah most definitely carries the connotation of romance.

n