8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

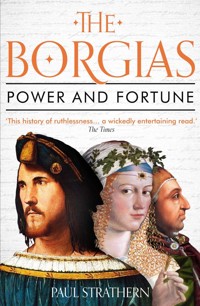

'A wickedly entertaining read' The Times A Daily Mail Book of the Week The sensational story of the rise and fall of one of the most notorious families in history, by the author of The Medici. The Borgias have become a byword for evil. Corruption, incest, ruthless megalomania, avarice and vicious cruelty - all have been associated with their name. But the story of this remarkable family is far more than a tale of sensational depravities, it also marks a decisive turning point in European history. The rise and fall of the Borgias held centre stage during the golden age of the Italian Renaissance and they were the leading players at the very moment when our modern world was creating itself. Within this context the Renaissance itself takes on a very different aspect. Was the corruption part of this creation, or vice versa? Would one have been possible without the other? From the family's Spanish roots and the papacy of Rodrigo Borgia, to the lives of his infamous offspring, Lucrezia and Cesare - the hero who dazzled Machiavelli, but also the man who befriended Leonardo da Vinci - Paul Strathern relates this influential family to their time, together with the world which enabled them to flourish, and tells the story of this great dynasty as never before.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

THEBORGIAS

ALSO BY PAUL STRATHERN

Mendeleyev’s Dream

Dr Strangelove’s Game

The Medici

Napoleon in Egypt

The Artist, the Philosopher and the Warrior

Death in Florence

The Spirit of Venice

The Venetians

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Paul Strathern, 2019

The moral right of Paul Strathern to be identified as the authorof this work has been asserted by him in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, withoutthe prior permission of both the copyright owner andthe above publisher of this book.

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-544-0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-964-6

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-546-4

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-545-7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To

Julian Alexanderagent extraordinaire

CONTENTS

Maps

Abbreviated Borgia Family Tree

Dramatis Personae

Prologue: The Crowning Moment

1 Origins of a Dynasty

2 The Young Rodrigo

3 Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia Emerges in His True Colours

4 The Way to the Top

5 A New Pope in a New Era

6 ‘The Scourge of God’

7 The Best of Plans . . .

8 A Crucial Realignment

9 A Royal Connection

10 Il Valentino’s Campaign

11 Biding Time

12 The Second Romagna Campaign

13 The Borgias in excelsis

14 Cesare Strikes Out

15 Changing Fortunes

16 Cesare Survives

17 Borgia’s ‘Reconciliation’

18 Lucrezia in Ferrara

19 The Unforeseen

20 Desperate Fortune

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Sources

Illustrations

Index

ABBREVIATED BORGIA FAMILY TREE

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

This list is not exhaustive. If any names you are looking for do not appear, try looking up the page of their first entry in the Index.

Alexander VI Born Rodrigo Borgia, he rose during the papacy of his uncle, who became Pope Callixtus III.

Alfonso II Son of King Ferrante I of Naples, whom he succeeded as short-lived King of Naples.

King Alfonso of Aragon Made controversial heir to the throne of Naples by Joanna II. The future Callixtus III became his secretary.

Georges d’Amboise Archbishop of Rouen and a powerful influence at the French royal court.

Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie Illegitimate son of King Alfonso II of Naples, whose father was Ferrante I. Alfonso became Lucrezia’s beloved second husband.

Sancia of Aragon Spirited childhood friend of Lucrezia Borgia, who fell in and out of favour with Alexander VI.

Cardinal Basilios Bessarion Greek scholar who was at one time a candidate for the papacy.

Pietro Bembo Venetian poet who wrote sonnets to Lucrezia Borgia when she was living in Ferrara and married to the Duke of Ferrara.

Alonso de Borja See Callixtus III.

Cesare Borgia Oldest son of Vanozza de’ Cattanei and Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, the future Alexander VI.

Giovanni Borgia Known as the Infans Romanus; the child who appeared in the Borgia family, whose parentage became a source of scandalous speculation.

Isabella Borgia Sister of Callixtus III, mother of Rodrigo, who became Alexander VI.

Juan Borgia Younger brother of Cesare Borgia, who much resented him.

Jofrè Borgia Fourth child of Rodrigo Borgia by Vanozza de’ Cattanei.

Lucrezia Borgia Daughter of Alexander VI, who married her off several times in pursuance of his political goals.

Pedro Luis Borgia Nephew of the man who would become Callixtus III, appointed by his uncle as Captain-General of the Papal Forces.

Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia See Alexander VI.

Pedro Calderon Nicknamed ‘Perotto’, who was Alexander VI’s unfortunate chamberlain.

Callixtus III, born Alfonso de Borja, the first Borgia Pope, who gave his nephew Rodrigo Borgia the all-important post of Vice-Chancellor.

Cardinal Angelo Capranica Loyal friend to Callixtus III.

Vanozza de’ Cattanei Mistress of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (Alexander VI) and mother of Cesare, Juan, Lucrezia and Jofrè.

Charles VIII The young King of France who invaded Italy.

Miguel da Corella Known as ‘the strangler’, one of Cesare Borgia’s closest Spanish commanders.

Alfonso d’Este Son of Ercole I d’Este, was ruler of Ferrara, became third husband of Lucrezia Borgia.

Ercole I d’Este Military leader, Duke of Ferrara, who grudgingly allowed his son to marry Lucrezia Borgia.

Isabella d’Este Cultured Marquesa of Mantua, who disliked Lucrezia Borgia. Had her portrait sketched by Leonardo.

Fiammetta de’ Michaelis The renowned Roman courtesan whom Cesare took as his mistress during the summer of 1500.

Giulia Farnese Sixteen-year-old who became mistress to the fifty-eight-year-old Alexander VI.

Ferrante I The long-lived King of Naples, whose death triggered the invasion of Italy by Charles VIII of France.

Francesco Gonzaga Duke of Mantua and husband to Isabella d’Este.

Francesco Guicciardini A contemporary historian and friend of Machiavelli.

Innocent VIII The Pope who preceded Alexander VI.

Joanna of Aragon At twenty-three became the second wife of the ageing King Ferrante I, and thus became Queen of Naples. Not to be mistaken for the earlier Queen Joanna II of Naples (see below) who had died before she was born.

Queen Joanna II of Naples Aged ruler of Naples who made Alfonso of Aragon her heir, thus antagonizing French claimants to the throne.

Ramiro da Lorqua Cesare Borgia’s most trusted Spanish commander.

Louis XII Formerly Louis of Orléans, who succeeded to the French throne after Charles VIII.

Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici Son of Lorenzo de’ Medici, who would became a cardinal aged thirteen, but fled Rome when Alexander VI became pope.

Lorenzo de’ Medici Also known as ‘the Magnificent’, the ruler of Florence.

Niccolò Machiavelli Notorious author of The Prince, contemporary historian and emissary for Florence to Cesare Borgia.

Federigo da Montefeltro Renowned condottiere who transformed Urbino into a Renaissance city.

Guidobaldo da Montefeltro Son of Federigo, who became a sworn enemy of Cesare Borgia.

Oliverotto da Fermo Originally a loyal commander of Cesare Borgia’s army in the Romagna.

Cardinal Giambattista Orsini Senior member of the Orsini clan who became a friend of Alexander VI.

Giulio Orsini Condottiere who together with his brother Paolo joined up with Cesare Borgia in the Romagna campaigns.

Paolo Orsini See previous entry.

Riario family Genoese relatives of the della Rovere family.

Francesco della Rovere The young ruler of Sinigalia

Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere Sworn enemy of Alexander VI, continually plotting against him.

Sancia See Sancia of Aragon.

Antonio di Monte Sansovino Humanist scholar appointed by Cesare Borgia as governor of his Romagna territories.

Gian Carlo Scalona Mantuan ambassador in Rome.

Cardinal Ascanio Sforza Influential cleric from Milan whose vote ensured Rodrigo Borgia would become Alexander VI.

Giovanni Sforza Lord of Pesaro and Lucrezia Borgia’s first husband.

Caterina Sforza Countess of Forli, who was taken prisoner by Cesare Borgia and Sixtus IV.

Gaspar Torella Cesare Borgia’s Spanish personal physician, who became an expert on syphilis.

Cardinal Giovanni Zeno Extremely wealthy Venetian cleric who lived in Rome. On his death Alexander VI took charge of his fortune.

PROLOGUE

THE CROWNING MOMENT

IN THE SUMMER OF 1492, amidst the stifling, malaria-infested heat of Rome, Pope Innocent VIII became unwell, and it was soon clear that he was seriously ill. He began suffering from stomach pains, and his digestion was severely affected. The Pope’s personal physicians proved for the most part unwilling to take any responsible role in administering to a patient who was so evidently close to death. This was understandable in an age where medicine remained primitive and suspicions of poisoning were rife, with punishments for such misdemeanours proving drastic in the extreme. Indeed, doing nothing was often less likely to harm the patient than administering the usual accepted treatments. However, amongst the Pope’s personal physicians was a Jewish doctor called Giacomo di San Genesio, who favoured his own advanced methods of medical treatment above the more medieval practices then current. Excessive bleeding with leeches was commonplace, and usually only served to weaken the patient. Similarly archaic was the administering of ‘elixirs of life’ containing gold or ground pearl or other exotic ingredients, whose sheer expense encouraged the expectation of efficacy. Instead, San Genesio was all for radical and experimental treatments, several of which would later be adopted by orthodox contemporary medicine. Unfortunately, many of these treatments had yet to evolve the modern refinements which accounted for their curative, rather than their hazardous properties. In order to cure Innocent VIII, Giacomo di San Genesio decided to perform ‘the world’s first blood transfusion’. This involved him bleeding the Pope, whilst at the same time inducing him to drink draughts of freshly drawn youthful blood, a treatment which would result in the death of three ten-year-old boys, before San Genesio was persuaded to desist. By then Innocent VIII had become so weak that he was able ‘to take for nourishment no more than a few drops of milk from the breast of a young woman’.

At the time, Italy was in the midst of what seemed to many like a golden age. According to the contemporary historian Francesco Guicciardini:

Since the fall of the Roman Empire, Italy has not experienced such peace and prosperity. The entire land has become adorned with magnificent princes and beautiful cities filled with noble minds learned in every branch of study and skilled in every branch of the arts.

This may have been a somewhat rosy view, but there was no denying that something momentous was taking place in Italy. The Renaissance, centred on Florence, was coming into its own, with the rebirth of classical learning, art and architecture inspiring the likes of Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. A new era of practical humanism was beginning to emerge, with its emphasis on the values and philosophical attitude adopted by an individual human being during the course of his or her life. This replaced the otherworldly preoccupations of the Middle Ages, during which our life on earth was seen as a necessary ordeal. After death, we would be judged and rewarded with a life in paradise or otherwise, dependent upon the good or evil which we had manifested during our earthly life. Put simply, during the Renaissance humanity was beginning to undergo a sea change. This marked an entirely new attitude towards life: one whose effects are still with us to this day.

Despite such advances, Innocent VIII retained a more medieval cast of mind, allied to a largely ineffective and corrupt character. Of part-Greek origin, it was said of him that he ‘begat eight boys and just as many girls, so that Rome might justly call him Father’. His eight-year reign had become a byword for corruption. His speciality had been the selling of pardons and indulgencies, allowing sinners to buy reductions in their time suffering the punishments of Purgatory, where their sins were purged, before their ascent into Paradise. When questioned on this matter, Innocent VIII replied, ‘Rather than the death of a sinner, God wills that he should live – and pay.’ One of the more notable features of his reign was his approval of the notorious Dominican friar Tomás de Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition. Another contribution came as a result of the Little Ice Age that had blighted crops and brought famine to northern Europe. Innocent VIII ascribed this to occult powers, and issued a bull authorizing the persecution of all witches and sorcerers as heretics, a move that led to widespread denunciations of personal enemies, settlings of old scores, as well as the judicial murders of ‘old wives’ and other defenceless women.

As knowledge concerning the illness of the Pope became more widespread, this gradually led to a breakdown of public order within his domains. Crime and civil unrest increased in Rome, where ‘hardly a day passed without a murder somewhere’. Meanwhile, in the city of Cesena, in the Papal States 150 miles to the north, there was an open revolt. In April news reached Rome that Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Medici ruler of Florence, had died at the age of forty-three. Innocent VIII had both admired and relied upon Lorenzo, and had even persuaded him to allow his eldest son to marry Lorenzo’s illegitimate daughter. In return for this favour, Innocent VIII had made Lorenzo’s thirteen-year-old son Giovanni de’ Medici a cardinal.* The charismatic Lorenzo the Magnificent was described by Innocent VIII as ‘the needle of the Italian compass’, in grateful recognition of his diplomatic skill in guiding the fortunes of Italy safely through the stormy seas of its turbulent politics. This entailed maintaining the balance of power in the peninsula, whose territory was mainly divided between the powerful and contentious city states of Venice, Milan, Florence, Rome and Naples. Now, with Lorenzo de’ Medici gone, and Innocent VIII dying, there appeared to be nothing to restrain each of these states from scheming to follow their self-interest at the expense of the others, a situation which would inevitably lead to a further bout of internecine wars.

Along with the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, there also came news from Florence of disturbing prophecies which had been made by the fiery fundamentalist priest Girolamo Savonarola. He had seen apocalyptic visions of ‘a black cross which stretched out its arms to cover the whole of the earth, upon which were inscribed the words: “The Cross of the Wrath of God”’, and he prophesied that ‘all mankind shall suffer the scourge of God’. More pertinently, some weeks earlier he had specifically ‘prophesied that Lorenzo the Magnificent, Pope Innocent VIII and King Ferrante of Naples would all soon die’. Lorenzo had now died, Pope Innocent appeared to be dying, and the sixty-nine-year-old King Ferrante, the paranoid tyrant of Naples, was said to be in failing health. The advent of the Renaissance was undermining many of the old certainties, and people throughout Italy were becoming bewildered by this age of change: Savonarola’s hellfire sermons harked back to an earlier age of primitive, unquestioned belief, while his visions seemed to fulfil the people’s forebodings of divine retribution. More and more of those who crowded to hear his sermons in Florence, the very epicentre of the Renaissance, were beginning to regress to the beliefs of the previous era.

As the long hot summer progressed, Innocent VIII gradually became weaker. Rumours swept Rome of the Pope’s more unorthodox medical treatment by di San Genesio, fuelling anti-Semitism. More substantial reports by the Mantuan ambassador Gian Carlo Scalona spoke of an angry shouting match in the dying pope’s bedchamber between two of the assembled senior cardinals. This had involved Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, the papal Vice-Chancellor, a wily, bullish figure, whose vigour belied his sixty-one years. Borgia’s adversary in this unseemly row had been his sworn, long-term enemy Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, who, despite his comparative youth, had emerged at the age of forty-eight as the most powerful figure amongst the College of Cardinals during the largely ineffective papacy of Innocent VIII. Whereas the Vice-Chancellor may be seen as the chief administrator of the Holy See (whose supreme ruler was, of course, the Pope), the College of Cardinals acted in the capacity of an advisory body to the pontiff.

In the course of Innocent VIII’s eight-year reign, he had incurred considerable disapproval for his distribution of papal offices amongst his family, as well as the selling of benefices and ecclesiastical privileges to the highest bidders. Such nepotism and simony had become an increasing feature of papal rule, though Innocent VIII’s behaviour in this regard had been regarded as excessive. However, on his deathbed Innocent VIII excelled even himself by declaring as his dying wish that the entire contents of the Vatican’s financial reserves be distributed amongst his relatives. This was estimated be worth around 47,000 ducats.* Such a pronouncement proved too much for Cardinal Borgia, much of whose efforts had gone into accumulating these reserves. Unable to contain himself, Cardinal Borgia chose to express his disapproval of this move in the presence of the Pope and his assembled cardinals. However, Cardinal della Rovere, in order to retain his favour with the Pope, had in fact ensured that the College of Cardinals agreed to Innocent VIII’s dying wish. Outraged at Cardinal Borgia’s disrespectful attitude, Cardinal della Rovere responded strongly, alluding in a contemptuous fashion to Cardinal Borgia’s Spanish origins. Cardinal Borgia, as Vice-Chancellor, was second only to the Pope himself in terms of administrative power; remaining as vigorous mentally as he was physically during his long years of office, he had grown unaccustomed to being contradicted, let alone insulted in such a fashion. Aggressively advancing towards della Rovere, Borgia informed him that if they had not been in the presence of the Pope himself, he would have taken matters into his own hands. Della Rovere stood his ground. In an effort to prevent an unholy brawl in the papal bedchamber, their colleagues had rushed forward, restraining the two cardinals in their revered scarlet robes from coming to blows.

Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia was particularly sensitive concerning his Spanish origins, of which he remained intensely proud. Anyone who cast aspersions on this proud heritage was noted – a target for future revenge. Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia would never forgive, let alone forget, any insult or act of betrayal. Indeed, second only to his driving ambition was his powerful and vindictive impulse to revenge. He might wait, often for years, but any disloyalty would eventually be avenged. As we shall see, this was a trait which ran more or less strongly through the entire Borgia family.

Innocent VIII finally died on 25 July, and on 6 August members of the College of Cardinals gathered for the conclave to elect the next pope. ‘They were twenty-three in number.’ Only four cardinals remained absent: the ones in Jerusalem, Bordeaux and Toledo, as well as Cardinal Borgia’s cousin Cardinal Luis Juan del Milà, who refused to attend, being averse to the heat of Rome.*

The conclave of 1492 was the first to be held in the Sistine Chapel, which had been restored by (and received its name from) della Rovere’s uncle Pope Sixtus IV†. By this time the high walls of the chapel had already been adorned with frescoes by the likes of Botticelli and Ghirlandaio, though Michelangelo’s ceiling would not be painted until some two decades later. Throughout the conclave the participating cardinals would be locked inside the chapel, in order to isolate them from outside influences. Conditions were oppressive, with the high windows boarded up and the inner chapel reduced to an oppressive gloom, illuminated only by candles. At night the cardinals shared plain wooden cells, sleeping on simple uncomfortable palliasses. Meals were carried to the chapel and passed through a hatchway by trusted janitors, the dishes meticulously inspected for hidden messages by the guards. These dishes consisted of frugal fare, in keeping with the oaths of poverty, chastity and obedience once taken by the clerical participants. However, this austere regime was not imposed to accord with priestly vows, but to encourage the conclave of wealthy cardinals unused to enduring such privation to reach a conclusion as hastily as possible.

After their tiring, uncomfortable nights, the candidates were free to wander up and down the dim confines of the chapel. Here the leading contenders and their supporters would engage in whispered conversation, bargaining, arm-twisting, attempting to gain sufficient votes. A two-thirds majority was needed before a successful candidate could be declared. This often required several votes. When an insufficient majority was obtained, the ballot papers would be burned, emitting black smoke from the chapel chimney – a sign recognized by the large, expectant crowds waiting outside. (When a successful candidate emerged, the ballot papers were burned with an added chemical – today, potassium chlorate – which produced the celebrated white smoke.) Following an unsuccessful vote, more urgent bargaining would ensue. The most serious deals were made when leading cardinals unobtrusively retired to the latrines – which remained unsluiced throughout the conclave, their pervasive stench adding further incentive for the cardinals to conclude their business.

Cardinal Borgia was well practised in the secretive procedures of the conclaves, having already attended those that elected Pius II, Paul II, Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII – whereas Cardinal della Rovere had only attended the previous conclave, which elected Innocent VIII. Even so, he had proved himself highly adept at the politicking involved. In the previous conclave, Cardinal Borgia had felt certain that he held sufficient votes to ensure his election, but a number of the Spanish cardinals (who could have been guaranteed to support their countryman) had failed to arrive at Rome in time. Cardinal della Rovere had mustered his followers to block Borgia, who had been forced to accept the compromise candidate suggested by della Rovere, who became Innocent VIII. It was this move which had given della Rovere such influence with Innocent VIII.

But now that Innocent VIII was dead, Borgia was determined that this time there would be no mistake. He well realized that at the age of sixty-one this was almost certainly his last chance of becoming pope. Despite his age, Borgia retained many of the qualities of his youth, when he had been described as ‘handsome, of a pleasant and cheerful countenance, with a sweet and persuasive manner’. Now, in late middle age, he appeared a rotund jovial character, but retained much of the menace which underlay the vigour of his younger years. However, this contradictory personality was not without his skills; the contemporary historian Guicciardini noted that he ‘possessed singular cunning and sagacity, excellent judgement, a marvellous efficacy in persuading, and an incredible dexterity and attentiveness when dealing with weighty matters’. These had been put to good use during his years as Vice-Chancellor, in the course of which he had accumulated all manner of papal offices, including ‘numerous abbeys in Italy and Spain, and his three bishoprics of Valencia, Porto and Cartagena’. According to Roman diarist Jacopo da Volterra, writing some years earlier: ‘He possesses more gold and riches of every kind than all the other cardinals combined, excepting only d’Estouteville.’*

However, as the Florentine historian Guicciardini noted, Borgia’s great riches, magnetic charm and administrative skills were not all that he possessed:

these qualities were far outweighed by his vices: the most obscene behaviour, insincerity, shamelessness, lying, faithlessness, impiety, insatiable avarice, immoderate ambition [and] a cruelty more than barbaric.

Borgia’s gross sensuality had quickly become evident. Even during his early years as Bishop of Valencia (a city he seldom visited), his degenerate lifestyle had attracted the attention of his superiors. Hearing of his ‘unbecoming behaviour at an entertainment given at Siena’, Pope Pius II had written to him: ‘Our displeasure is unspeakable,’ remonstrating that Borgia’s exploits were so scandalous that they brought disgrace upon the entire Church. Such warnings had been ignored. Around 1472 Cardinal Borgia had taken as his mistress a married Roman woman called Vanozza de’ Cattanei, by whom he had fathered four children. And now, some three decades later, at the approach of old age, his eye had fallen on the sixteen-year-old bride Giulia Farnese. Her husband Orsino Orsini may have been a member of one of the most powerful families in Rome, but he has been variously described in terms such as ‘squint-eyed and devoid of any meaningful self-confidence’. When he was persuaded to leave Rome on a pilgrimage, his wife, too, would become Borgia’s mistress; on Orsino’s return, he would take up residence in one of the family castles at Basanello, some fifty miles north of Rome.

Yet Borgia had never allowed such behaviour to interfere with his hold on power or his ultimate ambition. By the time of Innocent VIII’s death, it was thirty-six years since Cardinal Borgia’s uncle Pope Callixtus III had appointed him Vice-Chancellor, and according to Borgia’s secretary, ‘during that time he never missed a single consistory unless prevented by illness from attending, which very seldom happened’.*

Borgia considered that he had two serious rivals for the papacy. His main rival, Cardinal della Rovere, had the backing of King Charles VIII of France, at the time the richest and most powerful nation in Europe. Charles VIII had provided della Rovere with 200,000 ducats to garner votes amongst the ‘neutral’ cardinals. On top of this, the wealthy maritime republic of Genoa, della Rovere’s birthplace, had provided a further 100,000 ducats to his cause. Della Rovere also knew that he could count on the backing of King Ferrante of Naples. The divisions within the College of Cardinals mirrored the increasing tensions within Italy, with the result that this bloc was opposed by Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, the uncle of the ruler of Milan, who had every reason to be suspicious of his near-neighbour France, and was well aware of the antagonism of King Ferrante of Naples.

Such were the two favourites for the papacy: this time no one but Borgia himself felt that he was a serious candidate. The Spanish interloper was widely reviled. In the first vote, Cardinal Borgia and his supporters duly supported the candidacy of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, thus blocking Cardinal della Rovere. As the voting continued, it quickly became clear that a compromise candidate would have to be considered, if anyone was to gain the necessary two-thirds majority. But after four days and three votes the situation remained in stalemate. Then, quite unexpectedly, during the night of 10–11 August, a dramatic change took place. Just before dawn on 11 August, with the sky of Rome illuminated by flickers of summer lightning, the doors of the Sistine Chapel were unlocked and it was announced that Cardinal Borgia had been elected as the next pope.

This had come about because Cardinal Sforza had suddenly decided to cast his vote, and those of his supporters, for Cardinal Borgia. Cardinal Sforza had apparently decided that he had no chance of getting himself elected, and Cardinal Borgia had assured him that if he were elected he would appoint Cardinal Sforza as his vice-chancellor. Such was almost certainly the case; but it seems that this may not have been the entire story. The contemporary Roman writer Stefano Infessura recorded in his diary that during the hours of darkness on 10–11 August ‘the Vice-Chancellor [Borgia] sent four mules laden with silver to the palazzo of [Cardinal Sforza]’. The evidence of Guicciardini would seem to confirm this:

Primarily [Borgia’s] election was due to the fact that he had openly bought many of the cardinals’ votes in a manner unheard of in those times, partly with money and partly with promises of offices and benefices of his own, which were considerable.*

Although doubt has been cast on the colourful story of the overnight mule train, the financial dealings to which it alludes would seem to be supported by the fact that during these days the withdrawals from the Spannocchi Bank in Rome, where Cardinal Borgia deposited his money, were so massive that the bank almost went under.

There had been bargaining, arm-twisting and horse-trading during the course of previous conclaves, but this was the first time that the papacy had simply been bought outright. As the twentieth-century historian Marion Johnson observed: ‘It was a measure of the times that this could happen.’ Borgia decided to take as his papal name Alexander VI. This was widely seen as an allusion to Alexander the Great, rather than St Alexander, the second-century martyr, for Borgia had already blatantly named his son Cesare after Julius Caesar. Even before the white smoke had appeared from the Sistine chimney, the waiting crowd already knew the result. Scraps of paper had been thrown down from the Sistine Chapel windows containing the words: ‘We have for Pope Alexander VI, Rodrigo Borgia.’ When the newly appointed pope was presented to the public, it was customary for him to acknowledge his appointment modestly with the word ‘volo’ (‘if this is what you wish’). Instead, when Alexander VI appeared at the window of the Old St Peter’s he could not restrain himself from crying out exultantly: ‘I am pope! I am pope!’

The effect of Alexander VI’s election was immediate and dramatic. The young Cardinal de’ Medici was filled with alarm and exclaimed, ‘Flee, we are in the clutches of the wolf!’ before rushing back home to Florence. Meanwhile, Cardinal della Rovere fled to a fortress on the coast at Ostia, from where he would eventually set sail to France and live under the protection of Charles VIII.

Yet over the coming weeks the citizens of Rome, and beyond, gradually began to see a different picture. In the brief period between Innocent VIII’s final illness and the coronation of Alexander VI, no less than 220 murders had been recorded in Rome: now, the papal guards were despatched and order returned to the streets. Every Thursday Alexander VI would hold an audience, at which petitioners could place before him their grievances. Some even began to doubt the tales of his scandalous personal behaviour when they learned of the austere regime he had imposed on the papal household: expenditure was limited to just 20–30 ducats a day, while all dinners served at the papal table were to consist of just one course. Alexander VI announced that his declared aim for Italy was peace, and a unification of the Christian states to oppose the Ottoman Empire, which was continuing to expand through the Balkans and threaten Eastern Europe. At last, it seemed, the vast papal income – some 300,000 ducats in annual dues, collected throughout Western Christendom, whose varying limits extended from Greenland to Sicily, from Cadiz to Vienna – was to be put to good use.

This news was received with suspicion by the Venetians, but was welcomed by the Florentines. Even King Ferrante of Naples, who had harboured reservations concerning Borgia’s candidature, assured the new pope that he would behave towards him ‘as a good and obedient son’. At the same time, Ludovico Sforza of Milan rejoiced that his brother Ascanio was now the Pope’s right-hand man. For the first time in living memory Rome finally had a strong pope with a clear vision for the future.

The full extent of this vision – audacious in the extreme and far exceeding the imagination of any but Alexander VI himself – would only gradually become clear as his reign unfolded. For some, the Borgias have become a byword for utter depravity and ruthlessness. And their Spanish inclination towards superstition, particularly evident in Alexander VI, would prove a further alienating factor. Others have attempted to mitigate this picture, with mixed success. However, it would be the Florentine historian and diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli, a contemporary of the Borgias, who would grasp the heart of the matter. In the course of his work as a diplomat, Machiavelli would have intimate dealings with the Borgias; and it was this experience that gave him a crucial insight into their intentions. The stories of lurid depravity, ruthlessness and sadism served as little more than a smokescreen for their more dangerous ideas, as well as a warning to their enemies. There was so much more to the Borgias than mere self-aggrandizement and corrupt hedonism. They would stop at nothing: the main driving power behind the family was ambition. No considerations of morality or loyalty would be allowed to stand in their way. And the family’s ultimate ambitions were far more sensational than all the rumours concerning their behaviour. Indeed, when revealed they take one’s breath away.

So what were these fantastic ambitions which Alexander VI harboured in his heart at the time he became pope? No less than a united Italy: a return to the glories of Ancient Rome, ruled over by a hereditary Borgia ‘Prince’. On Alexander VI’s death, his son Cesare was to take over the papal powers, becoming in effect a hereditary pope. Years later, Machiavelli would write his notorious work The Prince, whose amorality gained him infamy throughout Europe. In this short work Machiavelli would set down, with chilling frankness, the methods by which a ‘prince’ (in effect, any ruler) could gain power – and, perhaps more importantly, retain this power. He gives a number of historical examples, illustrating the success or otherwise of their methods. One of his chief examples would be Cesare Borgia, whose chillingly brutal methods would best illustrate Machiavelli’s main requirements for success.

Machiavelli’s examples were devoid of gloss, morality or any other than personal justification. He distilled such harsh reality into the maxim: ‘Virtù e Fortuna’. This saying is open to widespread interpretation, from the more judicious ‘Power and Fortune’, to the informal, rule-of-thumb ‘Strength and Luck’. Machiavelli’s use of ‘Virtù’ has many connotations. Its original roots hark back to ‘vir’ (man), as well as ‘vis’ (strength), with connotations of ‘virility’. Though it also implies ‘virtue’. But this should not be mistaken for the Christian or even classical virtues of good, justice, compassion, prudent restraint and the like. If anything, it is more akin to the idea which would emerge several centuries after Machiavelli, with Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ and his ‘Superman’, who operated ‘beyond good and evil’. The meaning of ‘fortuna’ is more evident: fate, luck, chance or destiny are the most appropriate echoes. Yet it also contains an element of occasion or opportunity (to be seized). On the other hand, ‘Power and Fortune’ can be more crassly seen as ‘Guts and Luck’, and there would be times when the Borgias’ fortunes hung upon just such brash and dangerous opportunism and chance.

However, Alexander VI’s vision of a strong united Italy, under the power of Rome, was but the first stage in his ambitious strategy. Borgia’s predecessor, after whom he had named himself, was Alexander the Great. The man who had conquered Ancient Greece had not stopped at the borders of his early conquest. And Borgia, too, had a greater dream. One which would, perhaps, owing to his age, only be fully approached by his aptly named son Cesare. If successful, this dream would eventually have extended to a great empire, stretching from the Atlantic coast of the Borgias’ native Spain to the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Holy Land. This would have to be backed with military might sufficient to retake Byzantium and sweep the Ottoman Empire from the Levant – not such an unthinkable task, as we shall see. Here, in the mind of the new pope Alexander VI, was the embryonic dream of a new Roman Empire, a Renaissance realm echoing its classical predecessor.

Impossible? Implausible? Hindsight may reveal such ideas as a chimera. But it is important to bear in mind that these and similar dreams had long been in the air. Machiavelli’s writings would merely articulate this vision. Versions of such ideas would certainly not have been foreign to the crusaders of the previous centuries. And as the historian Machiavelli would have well understood, the precedent for the evolution of a great Roman Empire, well established in ancient history, was already a resurgent idea in fifteenth-century Italy. At the time, Florence was regarded by many as the new Athens. And as with the original Athens, the cultural innovations of Florence had grown up amidst a territory of squabbling city states. In the classical era, the cultural revolution of Athens and the Greek city states had given way to the military might and civil innovations of the great empire ruled from Ancient Rome. The ‘eternal city’ could well rise again. It is worth bearing in mind the existence of such dreams during the era we are about to describe.

The Renaissance had begun in Florence in the middle of the preceding century; this transformation of art, architecture and thought had now evolved and was beginning to spread north from Italy across the Alps into Germany and France. A spectacular unforeseen transformation of the western world had begun. The Renaissance may have been, in part at least, a rebirth of classical ideas, but it would also grow to include its own unique elements. Western Europe was developing a new, recognizably modern culture. Who could predict how this might evolve?

At the same time other events, of profound but unrealized significance, were already taking place. Again, with hindsight, we can see that the ascent of a ruthless Borgia to the papal throne in 1492 was but one of these events. In Spain, the last of the Muslim rulers surrendered to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile in January 1492. By October of the same year, Columbus had made landfall in the New World. Europe appeared poised to enter a new age where anything was possible. And Alexander VI was determined that the Borgias should play a leading role in any such historical development.

________________

* Twenty-four years later Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici would become Pope Leo X.

* At the time, an artisan would have been lucky to earn twenty-five ducats in a year. An adolescent female Caucasian slave could be bought for six ducats.

* Cardinal del Milà had attended his first conclave as early as 1458, but had found the Roman climate intolerable. The prospect of such discomfort would cause him to decline invitations to attend the six ensuing conclaves which took place during his lifetime.

†Sisto is a variant on the Italian sesto for ‘sixth’.

* Cardinal d’Estouteville, Bishop of Rouen, became a byword for vast wealth after he survived a serious outbreak of the Black Death in France, consequently declaring himself the possessor of the many bishoprics and benefices which had fallen vacant following the death of their incumbents.

* The consistory was the formal committee of cardinals which regularly met to advise the Pope. The Vice-Chancellor was its senior member. The consistory was made up of the limited amount of cardinals resident in Rome at the time, as distinct from the College of Cardinals, which included all cardinals, many of whom were resident in France, Spain, the German states or other more distant territories of Christendom.

* Upon assuming office, a pope was required to divest himself of all his bishoprics, benefices and other appointments.

CHAPTER 1

ORIGINS OF A DYNASTY

THE BORJA FAMILY (as they were known in Spain) originated from the remote hill town of Borja, some 150 miles west of Barcelona in the Kingdom of Aragon. This occupied the large wedge of eastern Spain south of the Pyrenees, including Catalonia. As we have seen, the first Borgia pope was Callixtus III, of whom it has been said: ‘The election to the papacy of Alonso de Borja as Callixtus III was little more than an accident, yet without it, there might never have been such a phenomenon as the Borgia Age.’

Alonso de Borja was born in 1378 near Valencia. During the early life of Alonso the fortunes of the Kingdom of Aragon would wax and wane. Even during its lesser periods it would be an important regional kingdom. In its glory days it would be the major power of the western Mediterranean, its territory extending to Corsica and Sardinia, as well as Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples. The latter occupied almost the entire southern half of Italy, while its ancient capital city – Naples – would become the third largest city in Europe and an important centre of the Renaissance. The population of Naples was at this time around 100,000, just below that of Venice and Milan.

According to long-standing family tradition, the Borjas had royal blood, being descended from eleventh-century King Ramiro I of Aragon. Although there is little evidence to support this, it is impossible to over-emphasize its importance in the self-conception of those members of the Borgia family who will play the leading roles in this history. In their eyes, the Borgias were the descendants of kings and were destined to become kings once more. Ironically, an exception to this driving psychological myth was Alonso de Borja. In some histories of the popes he is regarded as a nonentity before he ascended to the papal throne in his mid-seventies, and little better afterwards during his brief four-year reign. Such belittlement is not born out by the facts.

Alonso de Borja was the only son of an estate-owner outside Valencia. He evidently exhibited an early gift for learning, and was sent to the nearby University of Lerida, the third oldest such institution in the country, having been founded in 1300.* Here Alonso studied law, which he later went on to teach at Lerida, at the same time taking minor holy orders to become canon of the local cathedral. Entering the Church was unusual for an only son, who would have been expected to inherit and run the family estate. However, it must have become evident to his father that Alonso was neither suited, nor equipped for such a task. Alonso exhibited spiritual qualities which matched his intellectual abilities. He led an ascetic life and devoted himself to his studies. His academic distinction eventually brought him to the notice of the charismatic and ambitious twenty-one-year-old King Alfonso of Aragon, one of the first humanist leaders in Spain. King Alfonso is credited with the saying: ‘Old wood to burn, old wine to drink, old friends to trust, old books to read’; although this admirable contemporary attitude does not appear to have been reflected in his somewhat archaic attitude towards women: ‘Happy marriage requires that the wife be blind and the husband deaf.’ Despite this attitude, King Alfonso would so charm the ageing and childless Queen Joanna II of Naples that he she would later adopt him as her heir, much to the annoyance of the French claimant to the throne. The fulfilment of Queen Joanna II’s promise would involve great diplomatic tact, and it was here that Alonso de Borja’s clear-headed advice would prove invaluable.

At the age of thirty-eight Alonso de Borja was appointed to the influential and trusted post of secretary to the king. Apart from overseeing His Majesty’s affairs and duties, he was also required to undertake diplomatic missions involving considerable skill. At the time, western Christendom was split between two popes. The so-called Avignon line, with its stronghold in southern France, was represented by the ‘anti-pope’ Clement VIII; while the ‘true’ pope, elected by conclave in Italy, was Martin V. King Alfonso of Aragon had initially supported Clement VIII, but in order to strengthen his claim to the Kingdom of Naples, in 1428 he decided to switch sides. The tricky diplomatic task of leading the diplomatic mission to persuade Clement VIII to resign in favour of Martin V fell to Alonso de Borja. By now Borja was fifty years old, but neither the travelling involved, nor the authority of his opposition appeared to daunt him, and within a year Clement VIII had been persuaded to resign. This put an end to the schism which had divided the Church since the previous century. Martin V was so filled with gratitude that he made Alonso de Borja Bishop of Valencia. By 1442 King Alfonso had also become King of Naples, which title included King of Sicily and Jerusalem (this last being a purely nominal title, a hangover from the time of the crusades). King Alfonso now moved, along with his court, to southern Italy.

This displeased the new Pope Eugenius IV, who as pope remained officially – though in title alone – liege lord of the Kingdom of Naples, receiving an annual small symbolic payment of dues. Protocol dictated that King Alfonso should at least have ‘consulted’ the Pope on taking up residence in Naples. King Alfonso once again despatched Borja to effect a reconciliation, acknowledging the Pope as his liege lord. The success of these negotiations so delighted Pope Eugenius IV that he made Bishop Alonso Borja a cardinal.

Some sources claim that both of these negotiations were something of a foregone conclusion, requiring little expertise on behalf of the new Cardinal Alonso de Borja, Bishop of Valencia, yet there is no denying the importance of their outcomes. It was some time during this period that Alonso de Borja was despatched back to Spain on another important mission. He was instructed to educate King Alfonso’s adolescent illegitimate son Ferrante, schooling him in the Classics, courtly manners, and a smattering of the new humanist learning. King Alfonso then married off Ferrante to Isabelle of Clermont, the daughter of a high-ranking French aristocrat, whose family had links with the Orsini in Rome and large estates in southern Italy, as well as being a distant descendant of an earlier Queen of Naples. The illegitimate Ferrante was then declared to be King Alfonso’s legitimate heir.

Shortly after returning to Naples from his mission to educate Ferrante, Cardinal de Borja retired from the court of King Alfonso. His wish was to take up residence in Rome and spend his final years in the Holy City; but this was no simple matter, even for a cardinal. By this time, Rome was a shadow of its former glory. One and a half millennia previously, at the height of the Roman Empire, the city had supported a population of more than a million, its great buildings, triumphal arches and monuments the envy of Europe. With the decline and fall of the Empire, accompanied by various sackings by Vandals, Visigoths and similar barbarian tribes, its population had become seriously depleted, and so it had remained during the ensuing centuries. By the fifteenth century the population had sunk to less than 20,000, living amongst the crumbling ruins of the eternal city. Such was the lawlessness of this diminished citizenry that during the Avignon schism the so-called ‘Roman pope’, mindful of his safety, had frequently chosen to live elsewhere. Pilgrims were liable to be robbed, or worse, by the thieves and cutpurses who frequented the low taverns and bordellos. Officially the city was ruled by a governor, but in practice virtual anarchy prevailed. The aristocratic families lived in their fortress-palaces, guarded by their own liveried soldiers. These escorted their masters through the streets when they left for their more hospitable castles in the countryside during the hot summer months. The impoverished Roman population lived in makeshift shacks, often constructed with stones pillaged from the ancient ruins.

Cattle grazed in the once-sacred Forum and wandered at will down the triumphal avenues; pigs rooted for sustenance where they would; the beautiful gardens became small, inefficient farms, while street after street of empty houses decayed, forming breeding grounds for plague and lairs for bandits.

With the ending of the Avignon Schism, Pope Martin V attempted to take up residence in Rome, but this proved too insecure and he spent much of his papacy in Florence. It was not until after Eugenius IV was elected pope in 1431 that the situation changed. The turning point came after Eugenius IV was forced to flee down the Tiber in a boat, being pelted with stones and refuse by citizens lining either bank. Thereupon he appointed Bishop Ludovico Trevisano as Captain-General of the Papal Forces. A bullish, hard-faced aggressive character, Trevisano quickly gained the nickname ‘Scarampo’ (the Scrapper). After restoring order to the streets of Rome with punitive thoroughness, Bishop Trevisano led the Papal Forces north to subdue the Papal States. In theory at least, the Papal States stretched north across the Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic Coast, then further north across the badlands of the Romagna as far as Bologna. In practice, Bishop Trevisano’s campaign was little more than an incursion into this territory, inflicting damage and acting as a warning to the local tyrants and warlords. During the course of his campaign, Bishop Trevisano made a point of seizing as much booty as he could. This not only prevented his defeated enemies from hiring mercenaries to regain their territory, but also meant that he returned to Rome one of the richest bishops of his time. In gratitude, Eugenius IV made him a cardinal, whose benefices added further to his riches.

Yet these military exercises served their purpose by enabling Eugenius IV to take up permanent residence in the crumbling quarters of St Peter’s, which would be linked to the nearby impregnable Castel Sant’Angelo by a discreet passage for use in case of emergency. From this time on, the city of Rome would gradually return to the fold of civilized Italy. In practice, this meant that pilgrims were now fleeced, rather than mugged or murdered. But it also meant that the locals – from aristocrats and cardinals to the common people – were able to live a semblance of normal life. Riots were limited to occasions when the authorities incurred popular displeasure. Such was the new Rome to which Cardinal Alonso de Borja retired in 1445, after leaving the service of King Alfonso of Naples.

By the time Eugenius IV died in 1447 the influence of the Florentine Renaissance had begun to spread to Rome. At the accession of the next pope, Nicholas V, a number of new churches were under construction, though the Pope himself often appeared more interested in his own fortune than that of the Church. During his eight-year reign, Nicholas V built up an extensive collection of ancient books, manuscripts and paintings. The aristocratic families, too, began to flourish, adorning their palazzi with treasures and works of art. Despite this cultural reawakening, Cardinal Alonso de Borja continued to live a modest, reclusive life, regularly attending the Church of Santi Quattro Coronati, which had been entrusted to him along with his cardinal’s hat. And it was during this period that Cardinal de Borja became known as Cardinal Borgia, the Latinized form of his name.

In March 1455 Nicholas V died, necessitating a conclave of all available cardinals. ‘By the time of the conclave of April 1455 [Cardinal Alonso de Borgia] was living in Rome, an austere, modest and increasingly gouty old man in his late seventies.’ On this occasion fifteen cardinals assembled for the conclave. The obvious choice for pope was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, ‘by far the most intelligent and cultivated churchman in Rome’. Added to this was the fact that he had once been a metropolitan bishop of the Orthodox Church in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). This had been the capital of the eastern realm of Christendom, which some 400 years previously had split from the western realm, thus accounting for the latter being known as the Roman Catholic Church. Prior to the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Bessarion and a stream of Orthodox monks had fled west, bringing with them much treasure and many ancient classical works (especially by Plato), which had long since vanished from western Europe. In time, these works would be translated from the Ancient Greek (which remained barely understood in Western Christendom) and have a transformative effect on Christian doctrine, giving its faith a basic intellectual underpinning in Platonism. As a Metropolitan Bishop, Cardinal Bessarion also retained some authority and respect in the realms of the Orthodox Church, which was still holding out against the Ottomans in Serbia, northern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and the Greek Peloponnese (where a new Byzantine capital had been established at Mystras).* Bessarion was the obvious man to bring about the ultimate reconciliation between the Roman Catholic Church and its Orthodox counterpart during its time of need, indeed when the latter was fighting for its very survival.

Common sense may have dictated that the conclave should vote in Cardinal Bessarion as the next pope, but this was not to be. Bessarion remained deeply resented for his superior learning, but most of all because he was Greek, and even continued to dress like an Orthodox priest, growing a long beard, beneath which he wore an Orthodox cross.† Many thought his election might even suggest that the Catholic cardinals considered the Orthodox Church to be in some way superior. Even so, there was no denying that he was the best equipped candidate for the job. So in order to teach him a lesson in humility, it was decided that Bessarion should be made to wait. Instead, the conclave chose to vote in the obscure and ailing Cardinal Alonso de Borgia, who was ‘in such poor health that it was doubted that he would survive the arduous ceremonies of his coronation’. These were undoubtedly something of an endurance test – involving days of slow, lengthy processions past the crowds lining the sweltering streets of Rome, punctuated by the even more arduous task of having to conduct a series of lengthy services in churches throughout the city. A distinctly gruelling induction, which had so exhausted several previous (younger) candidates that they had been forced to retire to their bed for several days afterwards.

As it happened, the people of Rome were outraged that a ‘Catalan’ had been elected pope, and Callixtus III’s triumphal processions through the streets of Rome were roughed up several times by gangs of Orsini and Colonna thugs. On one occasion they even broke through the protective line of papal soldiers, almost dislodging Callixtus III from his horse.

The main part of the celebrations involved the new pope and his entourage of cardinals, dignitaries and protective soldiers making their way in procession down the long route through the centre of Rome. This started from the papal residence at St Peter’s, crossed the Tiber, proceeded past the dwarfing ruins of the Colosseum and the church of San Clemente, ending up three miles later at the Lateran (Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano) close to the western city wall. Here at the Lateran, the ceremony of the Pope’s official enthronement would take place, in the church he inherited as Bishop of Rome. This church was at the time arguably the most sacred site in Rome, being the repository of a large number of ancient holy relics, including no less than ‘the wooden table where Christ ate with his Apostles, about three braccia square’.*

At a certain point in the Pope’s enthronement procession it was customary for him either to avert his eyes, dismount or make a detour to avoid encountering a particularly notorious statue just past San Clemente. Numerous pilgrims (including Luther himself) record that this statue portrayed the notorious female Pope Joan, who is said to have reigned for two years until 1099, when she died giving birth to a child. Despite the fact that most historians now discount ‘Pope Joan’ as a purely legendary figure, the statue itself was certainly real and was said to have been erected at the very spot where she died in childbirth. It is known to have been destroyed in 1600.

Possibly as a consequence of Pope Joan, legendary or otherwise, each new pope, during the course of his enthronement at the Lateran would be required to take part in an intimate ceremony. During this, he ‘is seated in a chair of porphyry, which is pierced for this purpose, that one of the younger cardinals may make proof of his sex’. The young cardinal would reach up through the hole in order to establish that the new pope had testicles, before proclaiming: ‘Duos habet et bene pedentes’ (‘He has two and they dangle well’).

Callixtus III would turn out to be made of much sterner stuff than his electors had bargained for, and, despite his surprise at being elected, he quickly began leaving his stamp on the Holy See. One of the new pope’s first demands was to see the account books. These he scrutinized, and was horrified at the extravagances they revealed. Why, his predecessor Nicholas V had, during his eight-year reign, run up debts of no less than 70,432 florins.* ‘See how the treasures of the Church have been wasted!’ Callixtus III exclaimed on entering the Vatican Library for the first time. Such a treasury of rare manuscripts, books and works of art he regarded as superfluous to the offices and purposes of the Holy See. Callixtus III may have been a man of great spiritual refinement, but he had little regard for art. This did not mean that he was a philistine, more that his aesthetic taste was limited. Fortunately, in this field he had come to rely upon the advice of his favourite sister Isabella, the mother of Rodrigo Borgia. Isabella ensured that despite the new pope’s restriction on funds, the building of a number of Renaissance-style churches in Rome continued. Having suffered from years of neglect during the Great Schism with Avignon, Rome was desperately in need of some modern Christian grandeur amongst the rubble and towering ruins of pagan Ancient Rome. Isabella also persuaded Callixtus III to use Spanish artists. Most notable of these was Juan Rexach, whose modern influence stemmed from the Flemish School. These artists were the first to propagate the use of oil paint, which would in turn have a transformative effect on Renaissance art. Characteristically, Callixtus III was more concerned with the newly expanding city itself and improving its urban conditions. It was during his reign that the Campo de’ Fiori (‘Field of Flowers’), across the Tiber a mile or so south of the Vatican, was paved over to become a piazza. This led to a regeneration of a neglected part of the city, and the piazza itself would soon become renowned for the aristocratic palaces built around its edges.

Even so, the reign of Callixtus III would be characterized by an absence of the usual ostentatious display. At the same time many papal treasures would be sold off, and this income put to good use. None would be exempt from this new austerity, even the Pope himself. An example would be set: the papal household would cut out all public extravagances. (As we have seen, his nephew Rodrigo Borgia, the future Pope Alexander VI, would quickly grasp the propaganda value of such a gesture amongst his more deprived flock in the city of Rome, and beyond, as word of the Pope’s priestly frugality spread. However, consistent observance of such niceties would prove another matter where Alexander VI was concerned, as we shall see.)

Despite Callixtus III’s insistence upon austerity, this was not to be his overriding concern:

Deeply pious, dry as dust and crippled by gout,* Callixtus devoted himself to two consuming ambitions. The first was to organize a European crusade that would deliver Constantinople from the Turks; the second was to advance the fortunes of his family and compatriots.

Callixtus III was the first Spanish pope of the Roman Catholic Church, and as such was deeply resented by the leading aristocratic families of Rome, such as the Orsini and the Colonna, from amongst whom the popes were frequently elected. Not only did these families have a xenophobic distaste for this ‘Catalan’, but they were determined to do what they could to obstruct (or even to disobey) his wishes, anticipating that his reign would soon be over. Only by appointing loyal Spaniards to senior posts around him could Callixtus III be sure that his orders would be followed. Unlike so many previous popes of the period, he had remained faithful to his vow of chastity, and thus had no immediate family, no illegitimate sons upon whom he could rely by appointing them to positions of power. So instead he was forced to turn to his cousins, nephews and other Spanish relatives he knew he could trust.

Rodrigo’s elder brother Pedro Luis Borgia was made Duke of Spoleto, Captain-General of the Papal Forces, and governor of the formidable Castel Sant’Angelo. This was the fortress which guarded the strategic Ponte Sant’Angelo across the Tiber from historic Rome to the district of Trastevere (Trans-Tiber). Much of Trastevere was occupied by the Vatican, which nonetheless remained within the protection of the ancient city walls. With Pedro Luis Borgia ensuring the loyalty of the Papal Forces, this served to secure Callixtus III against any menace from personal forces owned or hired by the antagonistic aristocratic families of Rome, such as the Orsini, the Savelli and the Colonna.