4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Myriad Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

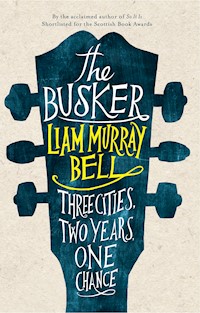

Three cities, two years, one chance: from the author of the critically acclaimed debut So It Is — shortlisted for best first book at the Scottish Book Awards 2013 — comes the hard-hitting story of a young man determined to find his voice. Plucked from obscurity in Glasgow, Rab Dillon is about to become the next great protest singer. Seduced by promises of stardom, carrying only the guitar given to him by the girl who broke his heart, he travels down to London. There he records the debut album that will speak to the dispossessed, the disenfranchised and disheartened. One year later, he is sleeping rough on the streets of Brighton. A modern-day ballad set across three cities and two years, The Busker is a richly comic exposé of the music industry, the Occupy movement, homelessness, squatting — and failing to live up to the name you (almost) share with your hero. It is also the story of what survives when the flimsy dreams of fame fall apart.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Praise for So It Is

‘Shades of Brian Moore’s Lies of Silence abound in this no-holds-barred debut about an Irish republican paramilitary who becomes first hunter, then hunted… Bell resists clichés and stretches the tension out to a bitterly abrupt end in which there are no winners.’

Guardian

‘A fresh perspective on the Troubles.’

Observer

‘This confident debut alternates between two characters and invites us to speculate on the connection between them (the truth of which is tantalisingly deferred). The scenes dealing with young Aoife are beautifully handled. Though her story is harrowing, there are moments of humour and warmth that would seem to confirm her plaintive dictum: “It’s not always cruelty that shows through.”’

Financial Times

‘Very impressive.’

BBC Radio Ulster

‘No word is wasted, no imagery subdued in this powerful book… An emotional rollercoaster with a very thought-provoking ending where the true value of life is considered.’

We Love This Book

‘A deftly written, confident debut.’

Jess Richards, author of Snake Ropes

‘Combines a gripping narrative drive with a deep sensitivity to the language, thoughts and emotions of its characters.’

Times Higher Education

‘A mature exploration of a controversial and difficult subject… wisely choosing to place the human – not the political or paramilitary – story at the centre of the novel.’

Gutter magazine

‘By turns lyrical and brutal, Liam Murray Bell’s novel is a gripping and unforgettable literary debut. Interweaving an acutely observed coming-of-age story with a chilling account of one woman’s involvement in Republican paramilitary activity, So It Is unflinchingly examines the devastating impact of violence on individual lives. This is a first novel of astonishing maturity from a talent to watch.’

Paul Vlitos

‘Bell uses our present peacetime context to examine the impact of all that has gone before. The interwoven narrative of a contemporary character who seeks to bring some retribution to bear upon those figures that live amongst us still in Northern Ireland – those with plenty of secrets and lies in their closets – interestingly seems to offer some catharsis to our villains in their attempts to deal with their own past.’

Culture Northern Ireland

‘Had me close to tears… If you like your books gritty with more than a hint of truth… then you will enjoy this one.’

newbooks magazine

‘Vividly and sympathetically written.’

Whichbook

‘So It Is explores the physical and psychological devastation of the Northern Irish conflict on many levels with sensitivity and compassion… intelligent [and] carefully constructed.’

Pamreader

‘[Bell] knows how to tell a tale… It’s an ending with no winners. Women, Bell would have us believe, are here no different from men… A challenging political thriller cum coming-of-age story.’

bookoxygen

For Orla

Contents

BRIGHTON

‘Fuck it,’ I say. ‘It got us a bed for the night and a hot meal.’

‘And a bottle of wine.’

‘Château Shite.’

Neither of us mentions the benzos. We sit underneath the overhang of the promenade on Madeira Drive, eating the greasy kebab scraps we fought the seagulls for. One of the fat bastards we defeated watches us from the stones of the beach, his head twitching from side to side and his throat raising a note that is both question and protest.

‘Here.’ I fling him the curved yellow chilli pepper. ‘That’ll teach you, you beady-eyed wee gobshite.’

‘You didn’t need to do it, though, Rab; we could have managed,’ Sage murmurs.

‘Let it go. We needed the money, simple as that.’

‘Still, not like that.’

I shrug and look out to the pier. All the rides have closed for the night and the neon is starting to fade to ghostly twists and turns out at sea. Shouts and shrieked laughter drift from the beachfront bars, further along the seafront. At the tideline, a group of teenagers is trying to build a fire. They’ve only got damp, rotten wood.

‘I’d been thinking of doing it for a while,’ I say.

‘We could’ve got you a gig instead. There’s a friend of mine up in Kemptown who said…’

He sniffs, then snorts the lie back up before it’s fully out.

‘There were other things we could have done, at least.’

‘Like what – sell our bodies?’ I do a little dance for him, shaking my shoulders. It lets the draught in underneath my blanket. Sage watches dispassionately. He has wrapped his own blanket, stiff with stains and salt air, over his shoulders as a shawl. The dress shirt he wears beneath it bulges open at the bottom and a fold of white stomach, with a scrawled dark signature of hair across it, shows through. He doesn’t seem to feel the chill.

‘I used to teach a class on social theory – ’ he begins.

‘Let it go,’ I repeat.

‘Your guitar,’ he continues, ‘was your livelihood, your means of production. Give a man a fish and he’ll eat for a day, but give a man a fishing rod – ’

‘Is it not “but teach a man to fish…”?’

‘Let me finish.’ He gives me his stare. ‘Give a man a fishing rod and he’ll sell it and buy a fish.’

‘Ha.’ It’s mirthless, a word rather than laughter. ‘It seems so, mate, it seems so.’

It wasn’t meant to be this way. When I came down from Glasgow I had big plans. There would have been no chance of me pawning the acoustic guitar Maddie gave me for my eighteenth for the sake of a bed, bath, bite, bottle and benzo. Maybe I’d auction it off after the second album, to fund the coke habit or to crinkle handfuls of cash on to casino cloths – for charity, even – but I’d never have pawned it. Not for fifty quid. Not that guitar, the one from Maddie.

‘It’s not even the gigs,’ Sage says. ‘It’s the busking.’

Since we arrived in Brighton, I’ve spent my days sitting outside the shops on Church Road or at the underpass on Trafalgar Street, leading from the train station down to North Laine, picking out folk songs and covers but avoiding my own material. It’s a chore, scraping seventy-two pence in loose change from a Springsteen song or a pound coin for some Dougie MacLean. I don’t tell Sage that, though. I don’t want to admit to him that I’m sick of it.

He’s taken a deep wheeze of a breath. It’s his windbag way of launching into a lecture or supplication: get it all out in one go so that no one can interrupt him.

‘Busking is your way of participating in consumer culture, your only marketable skill in this capitalist system, the only thing that you can trade off.’ He takes a breath. ‘That guitar was a symbol as much as anything, Rab – of your willingness to participate in the sham and shame of it all.’

The seagull has haughtily hobbled away from the chilli pepper. I feel a flicker of frustration about that, because I’d harboured this vague notion that he might swallow the whole thing, pause to blink at us in alarm, and then explode into a fluttering of feathers. No such luck, though. He lives to fight another day.

‘I’m proud of you,’ Sage concludes. ‘In a way.’

‘Left with only the blanket on my back and the song in my heart.’ And the single benzo I kept back from last night. Sage doesn’t know about it. I tucked it into the top of my sock as soon as I realised that the pawn money wouldn’t stretch to more than one night of the high life.

‘The kids down there have a guitar.’ Sage points at the shadows on the shore. The fire beside them wisps out smoke, but there are no flames to speak of. They’re all probably educated to Oxbridge-entry level, with Duke of Ed. awards and internships and gap years abroad stitched into their CVs like Scout badges, but not one of them can build a fire.

‘What are you saying – steal it off them?’ I ask.

‘I would never say that.’ Sage picks at his lip underneath the fringe of his grey-streaked beard. Dry skin, maybe even the beginning of a cold sore, comes loose and is flicked to the side. ‘But you could ask them for a go, maybe, to keep your hand in.’

The boy who is plucking away at the guitar is making a sound that the chilli-canny seagull would be proud of, and someone is running their mouth up and down a harmonica by way of accompaniment. If I did go over there, if they were to hand me their instruments, I could give them a song that might earn me a swig from their cheap chest-pain cider, or a toke from the broken bone of their joint. Equally, though, I could earn myself a kicking. Sage should know that as well as anyone; he’s suffered more beat-downs than me in his time. He’s been woken with spit and piss. Or by being dragged down the street in his sleeping bag. You can’t rely on strangers to leave you in peace, never mind show you kindness.

‘I’ve no interest,’ I say, ‘not really. Tell me a story instead, Sage. I’ll close my eyes and you can tell me a story and I’ll see if I can sleep.’

I know this suggestion will please him. He used to be an associate lecturer at a university up in London. There were half-filled halls of students listening to him once upon a time. If he closes his own eyes, if he recalls his research word for word, then he can be back in academia for a moment or two.

‘Have I told you about the factory owner in China?’ he asks.

I shake my head, keeping my eyes closed. It doesn’t sound like ‘once upon a time’, but it might be perfect for sending me to sleep.

‘Well, just outside this city in China…’ He clears his throat. ‘Just outside is this factory where they make electronic components for these high-end American smartphones…’

His voice changes, shifts to a lower register. It’s a radio voice; it reminds me of the books on tape I used to listen to as a child. There’s a rough rasp to it that mixes melodiously with the shushing of the sea. If I listen imperfectly, if I mingle and meld the two together, then it reminds me of the whispers Maddie used in the moments before sleep.

‘A robotic arm could do the work, but labour is cheap and injuries are ignored so they use men, women and children instead. Children especially. They only need to say they’re of age. The manager is too fond of their nimble fingers to ask for documentation…’

My mind drifts to a memory of my last cup of coffee: holding it between the heels of my hands, curling my fingers in towards the scalding polystyrene.

‘The American company eventually gives the smartphone a limited release in the city: only a hundred will be sold. And the factory owner finds out about this and decides to take advantage – he wants to buy up the phones and sell them on at three times the price. So, when the launch day arrives, he has a long queue of these factory workers waiting, each of them with a white armband on so the minders can identify them…’

Maybe it’s the caffeine that’s keeping me awake. I don’t even like coffee, not really. But it keeps you warm and it keeps you walking that bit longer. Until, eventually, you find somewhere to slump and sleep.

‘Those in the queue without an armband – businessmen and trendy types – catch wind of this and start protesting, and it builds to a riot. The store doesn’t open and the phone isn’t sold, and there’s outrage all round. Everyone turns on the workers: the minders beat them for giving away the scheme, thinking of the loss of the bonus the factory owner promised them; and the businessmen and trendy types shout, “What were you queuing for when you don’t want the phones, don’t need them the way we do”.’

It doesn’t lull me to sleep as Maddie’s voice used to. It’s an emotionless story, without soul, that’s delivered in that flat, factual way Sage has. He’s expecting me to join the dots; he’s led me to the water but he’s damned if he’s going to tell me how to drink.

Opening my eyes, I glance across at my older companion. His own eyes are tightly closed; he’s probably imagining standing silently in front of a seminar group and waiting for the sharpest of the students to pass comment. I reach down into my sock for the last benzo. It has a stray thread caught in its markings, so I pick that off and slide the pill under my tongue. Then I look across at Sage again. He has one eye open, watching me. There is accusation in his stare.

‘What’s your point?’ I ask, peevishly. ‘That the factory owner was a prick? That both the minders and the workers were underpaid?’

He shakes his head. ‘No, you’ve missed the point, as usual.’

‘What was the point?’

‘You just took a pill, I saw you.’

I shrug. ‘It was the last one.’

‘You could have shared it, though.’

‘Let me sleep,’ I say, and curl myself in against the concrete curve of the wall. The change of position ruptures the cocoon of my blanket, but my thoughts begin to slip and slide towards sleep in spite of the numbness of my fingers and toes. The shifting sea advances up the stones of the beach and washes over me, but the tide is warm and it carries me off in the undercurrent –

I am along the shore at the nightclub beyond the car park, standing on the stage and watching the crowd beneath me, as they lap up against the footlights. Their murmurings are a constant background noise, occasionally interrupted by a screeched call or cry. Then I strike the first chord and all becomes calm. They part, right down the middle; they fold away to either side to create a path for Maddie, who stands at the back of the room, distinctive with her cropped blonde hair and that olive-green summer dress that falls from her shoulders and has to be hitched back up.

I don’t play beyond the first chord because I realise that I’m holding the guitar Maddie gave me, with the untrimmed strings spraying out from the tuning pegs. My fingers fall from the fret and I step forward to the microphone.

‘I have a story to tell,’ I say. ‘About this guitar.’

The crowd draws a breath. Maddie takes a step forward, then stands, waiting, in the centre of the parted sea of people. Her widened brown eyes are on me, those eyes that make me feel as if I’m on the cusp of saying something profound, that the next thing to come out of my mouth will change everything utterly. For better or worse.

‘Maddie,’ I say, ‘I had to pawn the guitar, this guitar.’

There are a couple of hisses and catcalls from the crowd on either side of her.

‘I had to pawn it, because I needed a bed and some pills.’

‘And food, don’t forget!’ someone shouts.

‘And food,’ I concede, with a smile. ‘But I got it back, Maddie. I must have.’ I wave it in the air in front of me. ‘It was only a matter of time until I got it back.’

Maddie is still looking up at me, but she’s not smiling. Instead there’s this look of intense concentration on her face, with the wrinkle of a frown on her forehead. I’ve only ever seen her look that way once before. I need to continue before the crowd, who are losing interest, burst their banks and she is carried away on their current.

‘So I went back to the pawn shop,’ I say, ‘and there was this seagull on the counter. And he told me that – ’

‘Seagulls can’t talk!’ someone objects.

‘Fine,’ I say into the microphone. ‘He let it be known that I could have it back in exchange for a yellow chilli pepper. Just a single yellow chilli pepper.’

Her frown has deepened. She glances away, off towards the back of the room as if looking for someone else.

‘And so I went searching around Brighton for a chilli pepper,’ I say. ‘It’s not that I didn’t value your gift, or that I think it’s only worth the chilli pepper, but the seagull – ’

‘Are these meant to be lyrics?’ someone shouts, from the crowd.

The booing starts towards the back of the room, but it builds as it reaches the front and it breaks as it reaches the edge of the stage. Hands stretch out to clutch at my trainers, dragging my feet out from under me. ‘That was meaningless!’ they chant. ‘Mean-ing-less! Mean-ing-less!’

The guitar has fallen to the side and is being driven, again and again, against the microphone stand until the wood splinters and breaks. Lying on my back, I twist my body and reach out a hand towards the wreckage of it, but the crowd have lifted me and are pulling me down from the stage, pulling me under, the weight of them on me as the air is squeezed from my lungs. I gasp and grasp and –

I wake with a crick in my neck that can’t be stretched away and a sense of rising panic that doesn’t fully leave me even after I’ve rubbed at my eyes and spied the yellow chilli pepper lying discarded on the concrete, with the seagull nowhere in sight.

There’s no way of telling the time, but there’s the soft orange glow of sunrise out at sea and the first yawning groans of traffic from up on the main road.

Sitting upright, I look across at Sage, who has slumped forward on to his knees and is snoring softly and trailing a line of saliva down the leg of his well-worn corduroy trousers. He is middle-aged, although I have never asked for specifics. His brown-grey hair is greasy and lank and settles into slicks at his sideburns so that it seems to melt like plastic into the untidy tangles of his beard. The skin that shows around his nose and eyes has been browned by the sun and wind, weathered rather than wrinkled. His eyes, when they are open, have enough by way of sharpness to hint at his intelligence, but the way he spills out from the top and sides of his charity-shop clothes means that he will never again be called handsome. Even after a wash and a shave, even with a suit and a dousing of aftershave, he’d still carry himself with that awkward loping gait that shows the weight he’s been lugging around all these years.

‘How does a homeless man get to be so fat?’ I mutter to myself, half-expecting a chorus of boos for my unkindness, for my lack of charity. There is no reaction, though. The crowd has gone. Maddie too.

I’m back to grey. To a day of walking until my feet pulse with pain, then resting until the cold gnaws. Of seeking something of substance to dull the nerves, numb my skin and draw myself inwards. Enough warmth to see me through until I can find a kipping point – beneath a child’s slide in a playground, in a doorway with a covering of cardboard turning to mulch, or a shelter down by the seafront – where I know I’ll wake with a policeman kicking at the soles of my shoes, telling me to move on.

Rising to my feet, I wrap the blanket tightly around my shoulders and begin to shuffle towards the stones of the beach. There is a tap beside the oyster stall and the ice-cold water from it will remove the fur that seems to have grown, like mould, across the surface of my teeth during the night. Collecting the water in my cupped hands, I drink. The water tastes faintly of last night’s kebab. I belch deeply and roll the flavour around on my tongue.

The fire down on the shore is out, and there’s a spattering of rain starting to hiss out any remaining embers, but I decide to make my way down anyway, to see if the youngsters have left anything worth salvaging. They might have set down a sloshing of cider, or a cast-off roach that has enough clinging to it for an early morning smoke.

I lift the plastic cider bottles, but they’ve drowned their half-smoked joints in the alcohol so that both are useless. Swinging my arm, I lob a bottle up and out towards the sea, watching as the liquid inside spills out in an arc. A seagull, startled by the movement, lets out a scolding cry and swoops off to another part of the beach.

In among the charred wood and blackened stone of the fire, something glints. Like a magpie, I’m drawn to it. I wipe ash away from it until I can see its markings. It’s the harmonica. A nice one: twelve-hole, chromatic, with a wood inlay. It is warm to the touch as I lift it.

Holding it an inch or so from my mouth, I blow up and down the length of it. Fractured notes, incomplete scales, sound out. I take a corner of my blanket and polish at the metal until the scorched scars from the fire fade. I raise it to my lips and blow a chord. Just one chord. And then, in the early morning, with no way of telling the time precisely, I begin to sing with all the breath in my lungs. The words are caught by the wind and swept along the length of deserted Brighton beach.

LONDON

‘Morning, Rob.’

I hear a voice and know, without looking, that it belongs to Pierce Price. It is a slow voice, a voice that carries a nasal note and adds a throat-clearing as punctuation at the end of every sentence.

‘What are you doing here?’ I ask, into the pillow.

‘Checking on my investment, buddy.’

Turning slowly, so that I don’t irritate the hangover, I peer up at him. He pushes his glasses up his nose with his index finger. I’d love to reach up and slap him right across the cheek, to see if it dislodges the bright grin. In the state I’m in, though, it would probably hurt me more than it would him. There is a shard of glass behind my eyes. Squinting into the early morning sunshine causes it to reflect blindingly, and movement causes it to shift and stab anew.

A bit of coke would sort me right out, no doubt. A zip-line to wakefulness, to a clear head. And Prick Price will have some. He always has a baggy – takes it with him like a packed lunch so he can swap the tastiest morsels. I’ll have to wheedle for it, though; I’ll have to pick his pocket or start with a ‘please sir’, because he’s a right fucking Dickensian villain about the stuff. ‘Buddyyy,’ he’ll say. ‘What kind of manager would I be if I let my prize asset do that before he was even out of bed.’

I go through the motions anyhow. It’ll be excruciating for a minute or two, but it’ll make the rest of his visit bearable. Question asked, I close my eyes and drown out his reply with the dub-step thumping in my head.

‘Go on,’ I say. There’s a routine to it. What you ask for three times will come true; he’s a simple man, is Pierce Price.

‘Really, Rob, it would be better if you did the work first, maybe, and then relaxed later.’

Rab, I think, it’s fucking Rab, you bell-end. ‘Be a mate for a minute, Pierce,’ I say. ‘Be a mate, not a manager.’

‘I’ll make you a deal,’ he says. ‘I’ll give you a line now if you promise to bring a new song to the studio tomorrow.’

‘Absolutely, mate, absolutely.’ I’d sign my soul away for the line he carefully trails out on to the bedside table, for the credit card he uses to chop it into shape and for the rolled-up fiver he hands over so I can snort it up.

Pierce is constantly nagging at me about studio time. It’s recording, not rehearsal, he says. As if the creative process can be scheduled: ten-thirty, write generation-defining anthem; eleven, cup of tea and a custard cream; eleven-thirty, record track in one take plus another for safety; then an early lunch before a fucking rinse and repeat in the afternoon.

‘It looks like you got cashback on my idea, anyway,’ Price says, as I collapse back on to the bed.

‘Cashback?’ I think he’s talking about the fiver that I’ve crumpled protectively into my fist – and the way the coke is fizzing about inside, dissolving that stubborn shard behind my eyes and tweaking energy into my muscles, means that I’m ready to fight him to the death for it. ‘What the fuck does that mean?’

‘I ran into her on the way up,’ Pierce says.

‘Who?’

‘I don’t know her name, do I?’ He smirks. ‘And I won’t judge you if you don’t either. But I told you that my plan was a good ’un. The Price is right, my friend – the Price is always right.’

I try to remember back to the night before. It was Pierce who’d suggested I make the trip to the camp at St Paul’s. The Occupy movement, he said, very trendy. Give you something to write about, give you some protest lyrics.

Felicity. I remember her name. Flick, for short. A performance poet, being filmed beside the neoclassical pillars by a French camera crew. Like them, I hadn’t understood a word that came out of her mouth. Except for that line about the government throwing out the baby and keeping the bathwater – I’d liked that. For the most part, though, I’d not been listening. I’d been inspecting the way her curled black hair was piled like knotted wool on the top of her head, and admiring the way that strands of it straggled down her cheeks as though a cat had clawed them loose.

She made a pleasant change from the earnest chappie with slicked-back hair and glasses who’d taken me to the side and spoken, at length, about the similarities between the Mafia and capitalism: banks as casinos, laundering money from toxic mortgages; lobbying as loan-sharking, with political funding holding an expectation of being repaid many times over; and companies running the equivalent of a protection racket, threatening to leave the country and rough up the economy if they don’t get their way over tax.

Until I’d found Flick, I’d been thinking of calling it a day. The camp is good for a wander, granted, but there’s a lot of standing around waiting for something to happen, and I’d struggled to strike up conversation with the clutches of folk sitting around.

‘Nice-looking girl,’ Pierce says. ‘You could write a song about her, maybe.’

‘No,’ I say.

‘OK, OK.’ A pause. ‘Did you learn anything, then, buddy?’

I shake my head, but it causes the hangover to rattle the edges of my cocaine high. So I drag a hand up from the warmth of the bedclothes and rub at my eyes until they tingle, then burn.

‘Anything about Occupy London, or about the riots?’ Pierce pauses to shift his glasses again, mentally sorting through the hashtags in his mind. ‘Student fees, youth unemployment, anything like that?’

‘We spoke about Palestine,’ I say.

That scares him. He’s liable to drop a settlement-worth of bricks out of his arse at the mention of it. ‘Not Palestine,’ he hisses. ‘You can’t sing about Palestine.’

Flick had placed a hand on my fretboard halfway through my work-in-progress song, just after the lyric about the St Paul’s camp being a settlement in a foreign land, turning into a fortress for those willing to take a stand. No, she said, with a soft smile that stirred both irritation and lust. That’s not quite right, she said. That makes us the aggressors, and we were here first. The city of London – small c – was here before the City of London – big C. They’re the Israelis; we’re the Palestinians.

‘It’s all in hand, Pierce,’ I say.

‘By the end of the week we really need to clock up some proper studio time.’

‘Definitely. I’ll have a new song for you tomorrow.’

It’s not the songs, though. I could turn up with Lennon and McCartney tomorrow and the session musicians we’ve got in would make it sound as if Sergeant Pepper had taken the Lonely Hearts Club Band hostage. Half the studio time is wasted on the producer editing out the torture – cleaning blood from the tracks.

Once Pierce has left and both cocaine and hangover have dulled to a numbness, I take my guitar to the window of the hotel room and look across London to St Paul’s. I can’t see the tents, only the dome of the cathedral itself, but I set to thinking about Flick anyway. Maybe I can write about giving her a night in a budget hotel room, away from the fabric catacomb – shit – or moving her from ground-mat to top-floor flat – shitter – tents to vol-au-vents – doesn’t even fucking rhyme.

Maybe I could write about the way that she clutched and clawed at my back, as if trying to break through the skin, and how I struggled to get into a rhythm because she was always stopping and taking up a new position. Then, finally, when I got into my stride, when I was grunting, gasping, gulping towards my goal, she pushed me out of her so that I spilt up into her belly-button. And I knew that I should be grateful for the cheat’s contraception, but I throbbed and felt deflated. Because she’d not been lost in the moment; there’d been no pace or intensity to it for her. She’d been lying there judging, measuring the moment at which I should be withdrawn.

Afterwards, she explored the room and tentatively fingered a miniature brandy bottle from the mini-bar. I smiled and said yes, that’s OK, it’s all paid for. Over the past six or seven weeks money has been draining from the account like sand through fingers, but I’m still confident there’ll be enough for a castle. Eventually. Once I’ve finished recording and we can move on to the release and begin thinking about touring.

‘How does it work?’ she asked, then.

‘What?’

‘Your record deal. Do they just give you free rein and you go off and write an album?’

‘Not quite. They give me an advance.’

‘An advance on what?’

‘On future royalties.’

‘Like credit?’

I shrug, then nod. She cracks open the bottle of brandy and tips her head back to drain it. Her naked body, stretched away from me, has no tan or trimming. There is a bruise, like a birthmark, down near her left hipbone, and her dark brown pubic hair is matted with what we’ve just done.

‘And who writes the songs?’

‘I do,’ I say, fascinated by the way she scratches at an itch just beneath her right breast without caring that I’m watching. ‘Well,’ I continue, ‘they have final say, of course.’

‘Of course?’ She stops scratching.

‘Yes. They’re the producers, they’re the label, they’re the ones with the experience. They know what sells.’

‘They’re your songs, though.’

I nod. ‘And?’

‘So surely you know what you’re trying to say, and surely that’s more important than what’s going to sell?’

‘Of course.’

‘Soooooo…’ She drags the word out, and lifts the bedsheet up and over herself, suddenly coy. ‘What are they about?’

‘My songs?’

She nods. She has wrapped the sheet into a toga, covering all but her face, one shoulder and her arms.

‘I played you one,’ I say. ‘Earlier.’

‘Yes, but what was it about?’

‘It was about Occupy, about the movement – ’

‘What was the message, though?’

I shrug and reach off to the bedside table for the menu. It is late and I’ve smoked skunk at the camp, shared two bottles of red at the pub and blown my load into this near-stranger’s belly-button, all without pausing for food. I have no patience for sitting on the sheets sifting through the sentiments behind my songs. I am hungry. Bloody ravenous.

‘Room service?’ I ask, waving the menu at her.

‘Do they have lobster?’

I’m not sure if she’s asking ironically, so I answer anyway. ‘I think this place is more cheese toastie than lobster thermidor.’

‘I love the way you say that – therrrmidor,’ she says, rolling it more like a pirate than a Scotsman, and crawling up the bed towards me on her hands and knees. ‘Therrrmidor. Is the food on credit as well?’ she asks.

‘Of course it is,’ I say, smiling. ‘Free ride, baby.’

GLASGOW

We always meet in the woods behind Hyndland station on a Friday evening to get drunk, even if it’s pissing down. It’s tradition and, Glaswegian weather or not, we stick to it like religion. A close-knit cult of five: three boys, two girls. No ceremony or idolatry to it, but a fair amount of confession and quite a bit of – unintentional – prostrating. There’s only one rule: drink until you can’t see the woods, can’t see the trees.

It’s on a mild night at the end of January, a few weeks into 2011, that Ewan brings Maddie along to even out the gender balance. Six of us now: three boys, three girls. He’s always had a roving eye for the ladies, Ewan, and it’s roved further afield since he left school last summer to get himself a full-time job at a shoe shop. This is the first time he’s brought someone along to be inducted into our weekly meet at the woods, though; the first time any of us has brought someone along. These aren’t fairytale woods, and if you’re looking for a fairytale romance then you’re better off going to the cinema in town, the café up at Broomhill Cross, or the pub down on Dumbarton Road that doesn’t ask for ID.

‘Nice to meet you all,’ Maddie says softly, bringing a hand up to give a wee wave.

‘Did you wear heels up that path?’ Teagan says. ‘That’s honestly absolutely mental. You’re lucky you didn’t break your leg.’

‘Ewan gave me a piggy-back.’

Ewan gives the rest of us a wink.

To get to the woods you have to walk up a stony path, on a steep incline, to the side of a hut with ‘Night & Day Security’ on a sign above it. The shop, nestled underneath the railway bridge, used to sell alarm systems, but it was broken into so many times that the owner tired of the irony and closed down. The path itself is neglected and overgrown: roots show through to trip you, thorny bushes pluck at your clothes, and the ground cracks and oozes moisture. At the top of the hill the path disappears into bogland, which sucks your trainers from your feet and sends splatters like stitching up the inside legs of your jeans. Only the wooden planks, thrown down in the worst of the wet weather, will lead you safely across to the fallen tree-trunk where everyone sits to drink.

‘Look what I brought.’ Ewan unfolds his jacket to reveal a litre bottle of vodka. ‘It’s going to be some night, guys.’

‘Where the fuck did you get that from?’ I ask.

‘This one – ’ Ewan nods over at Maddie, who’s crinkling her nose as Gemma spreads a ripped plastic bag out across the damp bark and indicates for her to take a seat with all the flourish of a maître d’ at a high-end restaurant ‘ – can pass for eighteen at the corner shop down beyond the university.’

‘You serious?’ Cammy looks over at Maddie in admiration. ‘Fuck me, that’s good. No more need to beg students to jump in for us or steal an inch from our parents’ bottles, then?’

Ewan nods. ‘I think the Paki in there might have a thing for her, to be honest.’

‘Ewan!’ Maddie’s voice is sharp but, as I sit myself down on the opposite end of the fallen tree, I’m not sure which part of Ewan’s comment she’s censuring. Whatever the race of the shopkeeper, I can certainly see why he might have a crush on Maddie. Oval-faced, with blonde hair cropped close and brown eyes that linger for a moment rather than flitting off as most people’s do, she’s pretty, certainly, but thoughtfullooking with it. The kind of girl you’d notice in a bookshop rather than in a nightclub.

It’s Teagan who begins the interrogation, once the cap has been twisted and the bottle begins to be passed from hand to hand.

‘What school do you go to, Maddie?’

‘Cleveden Secondary.’

‘What age are you?’

‘Sixteen.’

‘You doing your Highers?’

‘Yes. Maths, English, biology, modern studies and drama.’

‘Five.’

A pause. Teagan only did four, and she’s resitting one of those this year. Gemma takes up the baton.

‘How did you meet Ewan?’

‘At a concert,’ she says. ‘Though I had to drop my ticket three times before he finally noticed and picked it up for me. You need to give these lads plenty of opportunities to prove themselves gentlemen, you know.’

‘You like him, then?’ Gemma asks, smiling.

‘Sure.’

‘How much?’

A shrug.

Ewan doesn’t try to shield her from it, or even seem too bothered about her answers. He’s more interested in the vodka than the vodka-buyer. Soon enough the bottle is going between me and Ewan only, with the girls moving on to a bottle of white wine that Gemma pinched from a family party and Cammy complaining loudly about the crème de menthe he’s siphoned off from his gran’s supply but sipping away at it nonetheless.

‘You know Ewan’s a bum, right?’ Teagan asks.

‘How d’you mean?’ Maddie replies.

‘Well, he’s left school and he smokes dope more or less constantly and – ’

‘I have a full-time wage,’ Ewan interrupts. ‘Which is more than any of you have.’

‘And he’s my manager,’ I back him up.

‘And I’m his manager,’ Ewan agrees, taking the bottle from me.

‘Manager for what?’ Maddie asks.

‘I’m a singer,’ I say, with a shy smile that the vodka stretches into a smirk. ‘Singer-songwriter. I have a couple of songs up online, if you search Rab Dillon. D-I-L-L – ’

‘Are they any good?’

‘They’re mostly covers.’

I could tell her that I’ve changed the simple strum of the Nick Drake song to what my Uncle Brendan calls ‘pinch and tickle’ fingerpicking to make it my own, or how I changed the melody on the chorus of the Tom Waits song. Instead, I settle for a slight shrug that I hope will mark me out as a modest musical genius.

‘Here, Dildo.’ Ewan pushes the vodka bottle against my chest. ‘Let’s have a competition: who can down the most.’

‘Right.’ I accept the bottle, and the challenge, without question.

‘Stupid fucking alpha males,’ Teagan mutters.

‘Stupid fucking – ’

I don’t hear the end of Ewan’s reply because I’ve raised the bottle to my lips and I’m grimacing down as much of the vodka as I can. Cammy doesn’t help matters by thumping me on the back, supposedly in encouragement, so that the backwash bubbles up into the bottle. Stopping, I hold it out to Ewan, who repeats the process, except he uses a flailing arm to stop Cammy from helping him out. Three or four passes later, the bottle is empty. I win, by volume, in that I drank from the bottom of the red label down to the dregs, but it’s Ewan who finishes it off, throws the empty bottle into the weeds at the side and holds his hand out for Maddie. They rise, then, to go off and find somewhere quiet. There are catcalls and wolf-whistles from us all but, while Ewan turns around to give us a wink, Maddie pays us no heed and just keeps walking.

As soon as they’ve been swallowed by the bushes, the debrief begins.

‘Bit up herself, don’t you think?’ Teagan says.

‘She’s quiet, is all.’ Gemma replies.

‘I’d fuck her.’

‘Cammy!’

‘What? You saw the eyes on her – blowjob eyes, those.’

‘You’d fuck that tree if it had a hole small enough for your cock,’ I say.

‘What the hell are blowjob eyes, Cammy?’ Teagan asks.

‘Big wide eyes that stare up at me, all innocent, even when she’s got my cock – which is a perfectly respectable size, by the way – in her mouth.’

‘You watch too much porn, Cammy – far too much.’

‘Even still,’ he says. ‘I’d give her a face like a painter’s radio.’

‘What do you think, Rab?’ Gemma asks, cutting off Teagan’s disgusted squeal.

‘She’s not bad. Seems nice enough.’

‘He’s gay for Ewan, though,’ Teagan says. ‘So he’s not worth asking.’

‘What I’d not give for a go on those tits, anyway.’ Cammy concludes. ‘As Tea says, I watch a lot of porn, and those are the nicest tits I’ve ever seen.’

Within the hour, I’m in a position to confirm Cammy’s observation. I don’t intend to catch sight of Maddie’s right breast, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, but when I go stumbling off into the undergrowth for a piss there’s this rustling to my left and, as I start my stream, I squint over towards the movement and noise and see skin through the leaves. A perfect curve, pert and pale, with goose-pimples that are being smoothed by Ewan’s clutching, dirt-streaked hand. Turning mid-stream, I take a step to the side and peer to make out the pink dimple of the nipple. Then, cock in hand, I find my eyes travelling up to meet Maddie’s gaze. Over Ewan’s shoulder, she stares steadily across at me. A second passes; two, three. We watch one another, each in a compromised position, before I start to scrabble with my fly and belt buckle, covering myself and turning away. Maddie, for her part, makes no effort to hide her exposed breast or to alert Ewan to the fact that his best mate is peeping at them through the trees with his dick in his hand. Instead, with her eyes still fixed on me, she lets out a moaning gasp that carries across to me on the breeze.

It’s about half an hour later that she emerges from the bushes and comes to sit next to me on the fallen log. Teagan and Gemma have gone off to the chip shop to get themselves a fritter roll and flirt with the young Italian who works the fish fryer, and Cammy is trying drunkenly to climb a tree, swaying and snapping branches as he goes, but I have found myself unable to move. Either the vodka or the woodland sexshow, or both, have left me solitary, silent, and rooted to the uprooted tree-trunk.

‘Where’s Ewan?’ I ask.

‘He went off to pee or find someone or something.’ Maddie waves vaguely in the direction of the trees. Her hair is matted and mussed from lying on the ground and she has a smudge of dirt beneath her right eye but, to my eyes, she looks as if she’s been carefully made-up, modelled for a calendar shoot – cavewoman, maybe – with her white woollen jumper off one shoulder and the denim of her jeans camouflaged with a thin layer of dirt, twigs and leaves. ‘He’s very drunk,’ she concludes.

‘Who is?’

‘Ewan.’

‘Right.’ I nod, meet her gaze, then remember the last time we locked eyes and look away. There’s silence for a spell, until Maddie reaches into her pocket and brings out a packet of cigarettes.

‘You smoke?’

I nod and take one. Then I root in my jacket for a lighter and lean across to light hers. She cups my hand until it catches, her breath shallow, and, as her eyes come up to meet mine, all I can think about is Cammy’s earlier comment – blowjob eyes.

‘We didn’t do anything, you know,’ she says, after a drag.

‘What do I care?’

‘Just… we didn’t do anything. Other than a fumble in the jungle.’ She lets out a giggle at that, only a trickle of laughter. ‘Fumble in the jungle sounds dirtier than I meant.’

‘You like him?’ I ask.

A shrug, again.