9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

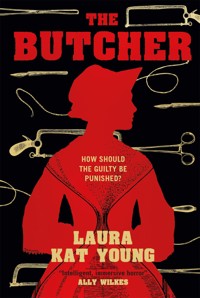

A suspenseful small-town horror novel of oppression, heartbreak and buried anguish – Shirley Jackson meets Never Let Me Go with the wild west setting of Westworld. When Lady Mae turns 18, she'll inherit her mother's job as the Butcher: dismembering Settlement Five's guilty residents as payment for their petty crimes. An index finger taken for spreading salacious gossip, a foot for blasphemy, no one is exempt from punishment. But one day Winona refuses to butcher a six-year-old boy. So their leaders, known as the Deputies, come to Lady Mae's house, and, right there in the living room, murder her mother for refusing her duties. Within twenty-four hours, now alone in the world, Lady Mae begins her new job. But a chance meeting years later puts her face to face with the Deputy that murdered her mother. Now Lady Mae must choose: will she flee, and start another life in the desolate mountains, forever running? Or will she seek vengeance for her mother's death even if it kills her? A devastating, alarming page-turner infused with melancholy, humanity – and society's maddening acceptance in the face of horror.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Bequeath

1

2

3

4

5

Part Two: Inherit

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Part Three: Relinquish

17

18

19

20

21

Acknowledgments

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Butcher

Print edition ISBN: 9781789099034

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789099041

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2022 Laura Kat Young. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Violet, Ilsa, and James.I love you always

PART ONE

BEQUEATH

1

When Lady Mae went into the kitchen to wash the dishes, she found that her mother had left her kit at home. It sat on her mother’s side of the old, worn table, inches from where Lady Mae stood. Though she had been taught from as far back as she could remember that inside the kit were her mother’s work tools—the ones for people in any case—lately, when Lady Mae found herself in the presence of the kit, there was a knocking at her breast and a speeding in her heart. The kit itself was small and ordinary, no bigger than the book containing Settlement Five’s bylaws. Alone, there on the table, the tools inside the kit remained harmless. But in her mother’s hands—and soon also her own—they commanded what Lady Mae had taken for respect. And that’s what it was, right? The bowed heads, the quiet that fell on the square when she and her mother walked into town. It was absolution, a kind of credence. Her mother had explained it to her over and over. It ain’t always like it seems. Right now it’s me, but soon it’ll be you. They don’t know no better. Maybe they didn’t, maybe they did. Maybe what they knew was so heavy and frightening, that to even look in the direction of it was impossible. And so when Lady Mae and her mother passed the other residents as they stood still on their porches with brooms in hand, their eyes stayed at the women’s feet lest they let it show.

Lady Mae stood next to the table and looked down at the kit. Its forgotten presence in itself did not cause Lady Mae alarm—perhaps today her mother was only working on the livestock and the tools she needed, bigger and sharper, were hanging on hooks in the back of the depot by the livestock pen. But if her job that day was an atonement, and her kit was still there in the shack—Lady Mae resolved that she’d bring it to the depot. If her mother had to return to the shack and fetch them, the Deputies might come around. They’d been worse lately, too, or so it seemed. But then another thought crossed her mind. In the seventeen years she’d been alive, Lady Mae had never disobeyed her mother purposefully. Not once, not ever. But that morning as the hot wind blew up against the kitchen window, she pulled out her mother’s rickety chair and sat down. She dragged the kit toward her, saw the cracked and shredded leather by the clasp. It looked like the skin of a fish salted and left to dry, and Lady Mae ran her fingers along the spine. She would leave her shack shortly and make the walk to the depot, but first she wanted to see what was inside.

The clasp was cool on her fingertips. There was no lock and key, no numerical combination to open it up. She simply pressed down on the horseshoe-shaped latch, and it popped open. Lady Mae opened it slowly, and as she did, saw firsthand what she had long known was in there: small tools made of shiny metal and buck-horned handles each in their own sleeve. She lifted out the scalpel. It was heavier than she expected it to be, and though its blade was no bigger than her smallest finger, she was careful. Even without touching it, it was sharp enough to cut through skin and muscle with ease.

Lady Mae went from left to right picking up and examining each tool—the clamp, the saw, the tourniquet, the file, the bone cutter. Each had its own purpose, but there at the table in the midmorning light, they did not seem big or weighty enough to remove a finger or a hand or an entire leg—how could her mother adequately do her job with such rudimentary tools? How would Lady Mae be expected to do so as well in less than a year? She looked at her hands, and though they were dry and cracked they were young still: would they be strong enough when the time came? If she wasn’t strong enough, where would it come from? Maybe she already had it. Maybe she was born with it, bequeathed from mother to daughter like everything else.

Lady Mae closed the kit and secured the clasp. She stood from the table, the chair creaking as it released her weight. It was nearly half past nine, and her lessons with Arbuckle started promptly after lunch. She’d have to be quick if she wished to make it back with enough time to ready herself for his arrival. Moving quickly, she took off her apron and pushed her dark curls up into her bonnet. Then she tucked the old kit underneath her arm and left the shack.

* * *

The day was already warm. The wind that blew from the west was hot and dry. Dust swirled around her, and the bottom of her skirts dragged along the dirt road. She couldn’t remember the last time it had rained; the hills that were usually lush and verdant were the color of silt. If lightning struck, the flames would easily catch and quickly blanket the hills with their orange light. There was no water between the hills and Settlement Five, and there wasn’t enough in the well to do anything besides put out a stove fire or two. The drought was unsettling, but Lady Mae and her mother had lived through worse. And their rations did not dwindle like that of the other residents’ in times of duress, though Lady Mae wished they did; receiving anything from the Deputies—especiallythat which the other residents did not get—made her sick.

The first rock struck the small of her back. It didn’t hurt, but she knew what it was and kept her eyes down to the ground. Her mother had told her: if the other children, especially the younger ones, saw how much their actions pained her, how it tormented her, they would never relent. And so she tried to ignore them as the pebbles and sticks soared through the air toward her. Instead, she focused on the tips of her boots and the way her fingernails felt on her palms, pressing into the skin until it was as though they would slice right through. The children called after her, their voices whirling together like a cyclone, trapping her in the middle of the road. A rock flew past her head. Another hit her in the shoulder. Laughter floated past her ears, and she looked to her right, catching a small body disappearing behind one of the shacks. It mattered not who it was—they were all the same: vile, unseemly beasts that had taunted and teased Lady Mae ever since she could remember.

She kept walking, digging her heels down in the dirt faster and faster until she was nearly running, tripping over laces that had become untied and kicking up the dust around her. She could see the depot down the road, its door open. Maybe her mother was watching and would come running out quick, throwing her body onto her daughter’s to protect her as she always had, as she had always promised she would.

“Your mother’s the devil!”

“You the devil!”

Lady Mae’s pulse skipped. A sudden sweat appeared at her hairline. The sun shone down, and there was the flash of metal off the tin roofs to her right. The children were better when her mother was around, who had more than once grabbed one by the ears or the collar and dragged them back to their own shack kicking and screaming. Their parents behaved accordingly, whipping and haranguing their children in front of the butcher in hopes it might lessen their own sentence when it came time. But her mother was not there in the dust with Lady Mae, and any elder that stood behind the tattered curtains of their front window offered nothing but a quiet disappearance from view. Did they hurt you too, Mama?

“I’m gonna cut off your fingers one by one!”

“I’m gonna make you eat them!”

She should’ve started running toward the depot, but in that moment, there in the road not ten meters from her shack, she stopped walking. As the rocks continued to belt her back, she lifted her arms to protect her head. But it was of no use. Someone had thrown one high in the air, and as it fell from above it landed squarely upon the top of her skull. Her body went limp and collapsed to the ground, and the children around her cried out joyfully, hatefully, their disgust seething in their veins. They had gotten the butcher’s daughter, maimed her as their parents had been. An eye for an eye, just as the Deputies preached.

“Scum!”

“You ain’t wanted!”

The children crowded around her in a circle. They shouted at her, kicked rocks and dirt into her face. They pulled her long curls out from under her bonnet and stomped on her back. They thought they had won—the butcher’s daughter lay prostrate on the ground—but as their taunting let up, as they turned to walk away, Lady Mae dragged herself up out of the dust. She crawled first to her hands and knees and spat. She put her hand to her skull, the warm blood stuck between strands of hair. The children stared at her, nudged each other with their elbows and walked back, silent and wondering, toward Lady Mae.

“I ain’t afraid. You ain’t nothing to me.”

Her lips moved, and she heard her own voice as the words drifted in the still summer air. The children stopped moving and stood, hands hanging from their sides, their tiny fists clutching stones. They watched Lady Mae stand up and take a step forward, slowly, purposefully, dragging her back foot to meet her front. She took another step, and then another and another still. Closer and closer she got to the beasts, their eyes, their little bodies, their heads shifting toward one another, unsure of what to do, as though scared that they weren’t as strong as they thought. She was Lady Mae, the butcher’s daughter, after all. But what they couldn’t know is that something had unmoored inside of her, and as the hot wind blew the dust up around her, she wiped the blood from her mouth, leaving a grotesque smear that went down the edge of her chin. The children, who thought themselves safe from any punishments—safe because Lady Mae had never told the Deputies of the treatment she endured—saw a flicker in her eyes, as if a wave of electricity had suddenly swelled up from deep down. She’d felt the rush before, many times in fact, but always it seemed too dangerous to embrace. When it bubbled up, she tried to push it back down for it went against her mother’s words instilled in her so long ago. It ain’t going to change nothing, her mother had said. You’re better than that, Lady Mae, she’d said, those kids need forgiveness just like everyone else. But in that moment, Lady Mae wondered if she was any better than the savages and how hard she could throw a fist-sized rock and how much blood would pour from their small heads. They didn’t deserve forgiveness, and Lady Mae was tired of blaming her injuries on chores, the woodpile, her own clumsiness. Her mother never believed her anyway. She was tired of running, and so as she squared her body toward the small group of children, she felt her fear unravel and make its way out of her.

“You better watch I don’t tell my ma,” she said. “Assault’s against the law.”

She’d never spoken to the children other than to yell stop you can’t no please. She’d never threatened them, and because of that they thought themselves invincible. Maybe they were. But maybe she was, too. After all, she had come from her mother, had inherited her eyes and mouth and high cheekbones; might she also have gotten the same strength that allowed her mother to go to the depot day in and day out?

“You ain’t gonna say nothing. We’ll make sure of that,” a boy called. It was the older Thompson boy, the meanest one, and he stood stuffed into an old shirt, dirt on his cheeks. He was ugly, and it wasn’t just because he was cruel. The younger one—too young to understand just how awful his brother was—ran up to Lady Mae and pushed her hard back onto the ground. Edith Cummings, the only girl in the group, threw a handful of gravel at her face. But Lady Mae, whose ears still rang and with eyes still blurry, rose to her knees again, the tiny stones cutting through her skirts, and looked the awful girl in the eyes.

“I ain’t afraid.”

She brushed the dirt from her hands. But she was weak, and the children were losing interest, calling to one another to leave her, that she ain’t nothing, nothing but a poor girl whose mother ought to be hanged. As quickly as it had churned through her, the strength vanished, and in its place she felt the familiar fear, the sticky panic underneath her fingernails.

“Come on,” yelled Balthazar Jones. “Let’s get out of here.” Being the oldest he gave the orders and the others listened. They backed away slowly, keeping their eyes on the butcher’s daughter. When they were far enough away, they turned and broke into a run.

“We’ll get you, Lady Mae! Ain’t nowhere to hide.”

“Come and get me,” she called after them too softly for them to hear. “Come and get me if you think you can.”

And as they disappeared from her view she felt her body again, bloodied and bruised. She rose to her feet, each step like fire whipping around her bones. She turned in the direction of the depot and began walking, knowing that when her mother saw her she would take Lady Mae into her arms and press her head against her chest. There she would hear the rhythmic beating of her mother’s heart, the life inside of her undeterred. But as Lady Mae approached the depot, she slowed. What would she say to her mother this time? How would she explain the blood, the bruises, the torn dress? Lady Mae didn’t know how to hold the rage that had filled her—her mother hadn’t taught her that—and she could not tell her mother of the burning resolve she’d felt to fight back, how though she’d felt it before, this time it was different. You ain’t give me words for it, Mama.

She walked gingerly up the depot’s porch steps, her feet heavy and hot. The door was open, but before Lady Mae called to her mother, she heard a man’s voice, low and growly. Peering through the window, she saw her mother bent over the man. Her mother’s back was to the window, and the man sat in the chair, a tourniquet around his forearm. Her mother held a saw in her left hand—the same kind of saw that was in her kit—and the sun, which had just lifted high in the sky, glinted off the blade. The man sat still. Lady Mae ducked down and leaned her back up against the splintered wood of the shack. She wasn’t allowed in the depot, not ever, and most likely she’d be in trouble if she was found peering in through the window. So she crouched and listened to her mother’s voice.

“You move the worse it’ll be,” her mother said.

“I ain’t gonna move,” the man said.

“That’s what you said last time.”

“Just do it already.”

“On three, then. One, two—”

There was a choking scream, one that gurgled far back in the man’s throat, and then Lady Mae heard a familiar sound, a grinding of metal to bone that was not unlike that which she heard when it was her turn to clean the chicken for a special meal. She listened: four, five, six, seven, eight, nine. And then her mother’s voice humming softly. In the sky, a small murder of crows bent and rippled, but none cried out.

She looked down at her own fingers and wondered how many layers of skin and muscle and bone there were. Would hers be warm and sticky where the skin pulled back, the phalanges jagged and sharp? What if the blood wouldn’t still and it flowed out of her until she was as dry as the earth? She felt a tightness in her jaw and the bubbling of spit in the back of her throat. Earlier that morning as she watched her mother ready herself for the day, she had wanted her mother’s hands to cup her face as she used to and tell her it was nothing, that it was just part of her job, that the patients really did deserve their atonements. But instead, her mother had grabbed her daughter’s wrists with each of her hands so tightly that Lady Mae saw the blood slowing as her mother’s knuckles turned white. Their arms held there, heavy and alike, in the empty space between their bodies. Lady Mae did not dare pull away.

“You must believe,” her mother had said. “You must trust. But above all, you must be careful of the questions you ask; the wrong one can lead you to the butcher, even if it’s me.”

Lady Mae lay the kit next to the door and crept away from the depot. The man in the chair—she hadn’t expected that, though she couldn’t be sure of what she expected. She knew what her mother did and that she was quick with it; whether it was an animal or a person, her hands were steady and precise. It was both exactly and completely unlike what Lady Mae had envisioned in her mind. Her mother had looked exquisitely barbaric standing over the man in the chair, her toes inches away from the blood on the floor. She knew there was blood—always there was blood; there wasn’t a single dress of her mother’s that didn’t have faded stains on the sleeves. But that wasn’t what had jarred Lady Mae—it had been her mother’s singing, the song she then recognized as the one her mother sang her when she was hurt or tired or sad; it was her mother’s job to maim, to console, and it would soon be Lady Mae’s job, too.

* * *

Although she walked home from the depot quickly, Arbuckle was already waiting outside her door. As she crossed the road, she watched him fan himself with his hat. Even from far away, his straight nose, his shoulders that were broad and thick were familiar. She didn’t want him to see her so ragged and maimed, and so she kept her head down. It was no use, though; he would certainly notice her injuries, as he was no stranger to mistreatment himself. He knew the difference between the mark of a hoof and that of a fist.

“Afternoon,” Arbuckle called. “I was just wondering where—” He stopped short as she came into view. “Lady Mae!” he cried, straightening up quickly and putting his hat back on. “What happened?”

“It’s no bother.” She walked up the porch steps and past him to her door. “Just some kids. Ain’t nothing I can’t handle.”

She avoided his eyes and swung the door wide so that she was not in his way when he walked over the threshold. She kept the left side of her face turned away from him and tilted down toward the ground. It made no difference for as he walked into the cool, dark shack he stopped and brought his hand to her cheek. The touch—kind and without motive—was electric on her skin. She looked up at him, at his worried brown eyes that she knew wished her a different life, and held his stare as best she could.

“Let me at least tend to it,” he said. He had questions, questions he would never ask aloud. She knew what they were and had long practiced her answers to them, hoping that the right words would convince him that what her mother did—what she’d have to do in a year’s time—was necessary. That’s what the Deputies said. People needed to eat just as much as they needed to repent. Arbuckle’s gentle hand slid down her face to her chin and held it gingerly. He stared at her for a moment and then brushed his soft thumb across the crusted blood that had dripped down from her head onto her cheek. She looked away to her left and pushed his hand from her face, but before she did her fingers felt his warm skin. She could not help but let her tears fall.

“Want me to go after them?” he asked as he stood before her. “Because I will. I ain’t afraid of them. They nothing but kids.”

“I wouldn’t want you to risk it. Ain’t no way my mama could give you atonements. Just as well be me.” She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand.

“I wouldn’t do nothing but talk.”

“Talking’s just as likely to get you in the chair as anything else.”

“I ain’t afraid, heck, someone ought to be saying something.”

“And that someone shouldn’t be you, Arbuckle. What would my ma think? Might not let you come around anymore.”

“But Lady Mae, you know I don’t believe—”

“I know, I know. But just leave it be. Won’t always be like this.”

Lady Mae could not remember a time in her life without Arbuckle, who was only two years older than her. He’d been coming around since he was small—four, five perhaps—and she was hard-pressed to conjure up a memory that he wasn’t in. She saw him nearly every day, and the days that he did not come by seemed long and dreary. He helped her with arithmetic beyond what her mother could, and in return, he received a small payment that Lady Mae knew he used for rations. His father spent their allowance on mash, filling up bottles instead of cupboards. He was the only friend she had ever had, the only one who did not hate or fear her, did not spit and hurl when she came near. Perhaps it was because Arbuckle himself knew the scorn of others; after all, many were maimed at his father’s cannery just as much as they were at the depot. His father had on many occasions failed to check the belt line before turning it on. Hands caught and fingers sliced off, falling to the factory’s floor with a quiet thump. This angered the law-abiding workers who were often mistaken for criminals, their missing limbs and digits betraying their innocence.

“You go on and clean up in the kitchen. I’ll fetch some bandages,” Arbuckle said as he walked through the doorway and placed his hat on the small table that held an oil lamp and an empty egg basket.

“It’s fine. I mean it. I ain’t going to have you play medic.”

“Go on.”

Lady Mae did as he said and went into the kitchen. She ladled out several cups of water into a bowl, and as the sediment swirled she dipped a towel in it and brought it to her face She wiped first her cheek and then held it to her head. The rough linen stung, and she dabbed at her hair and scalp tenderly but quick.

“Here,” Arbuckle said and came up behind her holding a piece of fabric and a small piece of adhesive.

“That won’t stick,” she said. “Just leave it.”

“Sure you don’t want me to do nothing?” Arbuckle asked. He put his hands on her shoulders and squeezed them lightly.

“It’ll just make it worse.” She pulled away from him feeling not for the first time a tumbling deep inside.

“I don’t know. Seems to me this is worse. They’d get atonements for sure.”

“Says you who goes on and on about how those atonements are bad.”

“This ain’t what I meant. Situations like this—”

“They’ll stop when it’s my turn.”

Arbuckle didn’t respond, and Lady Mae knew that would end the conversation. He didn’t like talking about when she’d take over at the depot. He thought atonements purposeless and cruel—wouldn’t say it directly to her, not as such, but all that thinking had to go somewhere. Arbuckle wasn’t wrong; after all, he’d seen his father go to the depot many times—small grievances over the use of a pasture, the stealing of another’s livestock, drinking too much and fighting in the square. Arbuckle’s father had not fingers, but ten stubs of differing lengths, and said as long as he could still open a jug of ale it was no matter to him. But his visits had not cured him of his meanness, and Arbuckle knew this well.

“Does it look that bad?”

His face softened, the stony disapproval vanishing. He took her chin into his fingers delicately. “Ain’t no hiding it.”

“I’ll say I wasn’t paying attention when I was cleaning the coop.” She reached up and took his hand from her chin, holding his fingers between hers for a heartbeat, a breath, a blink. Then she let it fall to his side.

“She won’t believe it,” he told her and pulled out the chair at the kitchen table. “You know she can’t do nothing if you don’t report it.”

“I ain’t need any more reasons for something like this to happen.”

Arbuckle sat down and breathed out slowly. His brow creased, his mouth twisting as if trying to keep inside the things they both knew not to talk about. “Up to you,” he said.

She licked her lips and felt the dried crumbs of blood, tasted her coppery insides. Arbuckle didn’t need to say anything for Lady Mae to hear him; the disapproval hung between his eyebrows. His jawbones rose and fell by his ears, the taste of worry fresh in his mouth. She tasted it, too; he was right as he always was.

He put his sack on the kitchen table and took out the book for the day. They were studying algebra, and he pulled out a small abacus as well, its wooden beads worn smooth from years of use. She was good at arithmetic, but what was in her mind was of little consequence; what would matter when she turned of age would be her hands, the steadiness of her long, slender fingers. Most important would be her constitution, and she knew this. If it were of salt like her mother’s she might be able to saw down to the last fragment, but if it weren’t, if it were mired—then what?

“You going to be able to do lessons today?” he asked, untying his kerchief. He blotted his forehead and his upper lip with it before opening the book to where they had left off the day before.

“Looks worse than it is. Come on.”

“Alright. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

“And don’t say I didn’t listen.”

He traced his finger down the thin page of the book. “I’ve got one for you.”

“Ain’t no problem no matter which way you figure.”

She’d been schooled at home—and always at home—since she could hold a pencil; she often found problems Arbuckle proclaimed difficult quite easy, and in her he’d met his match.

“At 1.62 ½ per cord, what would be the cost of a pile of wood 24 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 6 foot 3 inches high?” Arbuckle asked.

She took to her abacus then, sliding beads up and down and grabbing a pencil, wrote out an equation that Arbuckle had taught her a few months back. She quickly went back to the abacus to make a correction.

“Seven dollars, sixty-eight cents,” said Lady Mae.

Arbuckle flipped to the back of his primer to check the answer and smiled. “Right you are,” he said. And then, “That’s a lot of wood.”

“Like Willard’s stack—always peeking out. Aren’t you scared when you walk by?”

“No. It ain’t nothing to me,” he said and shook his head. “No such thing as ghosts.”

“Says you.”

Her eyes dropped back down to the abacus for a moment. What if I can’t, Mama.

“Arbuckle, can I ask you something?”

“You know you can.” He put the primer down and rested his elbows on the table, his hands clasped lightly together. Lady Mae felt young and foolish, the lump in her throat belying her demeanor.

“Your pa ever say anything to you after he sees her?”

“Like what?”

“Don’t know. Just anything, I guess. How she acts or what she says, maybe, if she says anything at all.” She twisted her fingers around one another as she spoke, tugging and pulling on her skin as if the answer she sought was just underneath.

Arbuckle leaned his head back and looked at the beamed ceiling, blackened from years of chimney smoke. “Well, I don’t know. Not that I can think directly.” He kept his dark eyes focused on the ceiling, and Lady Mae knew he was lying. Of course his father said things—they all said things. And of course he’d never tell her, never hurt or upset her knowingly. He’d grown up protecting her, putting both his mouth and body in between her and the rotten children that circled her.

“Will you tell me if he does?” she asked, hoping he’d never have anything to tell her.

“I sure will.”

She sat there and stared at the abacus on the table while Arbuckle flipped through the pages of the primer trying to find a problem that would stand up to Lady Mae’s mind. It was hot, and though the windows were open as far as they’d go, sweat dripped from both of them.

“I’ll get us something to drink.” She jumped up and went to the icebox, which was cool but not cold as they’d not had ice since the drought started, but at least the sweet tea would feel good on the throat. She poured out two glassfuls and set them on the table.

Arbuckle lifted the glass and brought it to his lips, sipping gingerly and with relief. “You and your ma sure do—”

“She was acting funny this morning.” Lady Mae picked up her tea and pressed her hot palms against the sides of the glass.

“What you mean?”

“Don’t know exactly. Quiet, I guess.”

But what she wanted to tell him was that morning, as she had been helping her mother hook her corset to the hidden band of buttons on her skirt, she noticed something fall out of her mother’s skirt and onto the floor. Lady Mae bent to pick the thing up off the floor—from where she stood it looked like a thimble—butwhen she put it between her fingers it was smooth and hard. Since it was dim in her mother’s room with the curtains drawn closed, she brought it close to her face. At first, she thought it was a dried piece of cheese from one of the traps, but as her eyes adjusted, she realized that she was holding a tip of a finger, its nail still on.