1,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dean Street Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

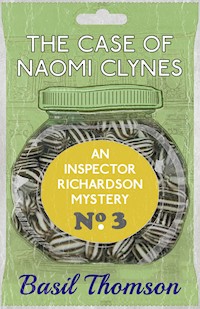

"The late Miss Clynes, sir? How dreadful. It must have been very sudden." "It was." Naomi Clynes was found dead, her head in the gas-oven. She left a suicide note, but Richardson, newly promoted to the rank of Inspector in the C.I.D., soon has cause to think this is a case of murder. With scarcely a clue beyond a postmark and a postage stamp, treasured by the deceased, he succeeds in bringing home the crime to a person whom no one would have suspected. The Case of Naomi Clynes was originally published in 1934. This new edition, the first in many decades, features an introduction by crime novelist Martin Edwards, author of acclaimed genre history The Golden Age of Murder. "Sir Basil Thomson is a past-master in the mysteries of Scotland Yard, and this novel is a highly capable piece of work…A brisk story, skilfully told." Times Literary Supplement "A first-class thriller. Written with lively vigour and a realism that can only come from an author who knows his subject, it can be wholeheartedly recommended as the best detective story of the week." Sunday Referee

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Basil ThomsonThe Case of Naomi Clynes

“The late Miss Clynes, sir? How dreadful. It must have been very sudden.”

“It was.”

Naomi Clynes was found dead, her head in the gas-oven. She left a suicide note, but Richardson, newly promoted to the rank of Inspector in the C.I.D., soon has cause to think this is a case of murder. With scarcely a clue beyond a postmark and a postage stamp, treasured by the deceased, he succeeds in bringing home the crime to a person whom no one would have suspected.

The Case of Naomi Clynes was originally published in 1934. This new edition, the first in many decades, features an introduction by crime novelist Martin Edwards, author of acclaimed genre history The Golden Age of Murder.

“Sir Basil Thomson is a past-master in the mysteries of Scotland Yard, and this novel is a highly capable piece of work…A brisk story, skilfully told.” Times Literary Supplement

“A first-class thriller. Written with lively vigour and a realism that can only come from an author who knows his subject, it can be wholeheartedly recommended as the best detective story of the week.” Sunday Referee

Contents

Introduction

SIR BASIL THOMSON’S stranger-than-fiction life was packed so full of incident that one can understand why his work as a crime novelist has been rather overlooked. This was a man whose CV included spells as a colonial administrator, prison governor, intelligence officer, and Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard. Among much else, he worked alongside the Prime Minister of Tonga (according to some accounts, he was the Prime Minister of Tonga), interrogated Mata Hari and Roger Casement (although not at the same time), and was sensationally convicted of an offence of indecency committed in Hyde Park. More than three-quarters of a century after his death, he deserves to be recognised for the contribution he made to developing the police procedural, a form of detective fiction that has enjoyed lasting popularity.

Basil Home Thomson was born in 1861 – the following year his father became Archbishop of York – and was educated at Eton before going up to New College. He left Oxford after a couple of terms, apparently as a result of suffering depression, and joined the Colonial Service. Assigned to Fiji, he became a stipendiary magistrate before moving to Tonga. Returning to England in 1893, he published South Sea Yarns, which is among the 22 books written by him which are listed in Allen J. Hubin’s comprehensive bibliography of crime fiction (although in some cases, the criminous content was limited).

Thomson was called to the Bar, but opted to become deputy governor of Liverpool Prison; he later served as governor of such prisons as Dartmoor and Wormwood Scrubs, and acted as secretary to the Prison Commission. In 1913, he became head of C.I.D., which acted as the enforcement arm of British military intelligence after war broke out. When the Dutch exotic dancer and alleged spy Mata Hari arrived in England in 1916, she was arrested and interviewed at length by Thomson at Scotland Yard; she was released, only to be shot the following year by a French firing squad. He gave an account of the interrogation in Queer People (1922).

Thomson was knighted, and given the additional responsibility of acting as Director of Intelligence at the Home Office, but in 1921, he was controversially ousted, prompting a heated debate in Parliament: according to The Times, “for a few minutes there was pandemonium”. The government argued that Thomson was at odds with the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir William Horwood (whose own career ended with an ignominious departure from office seven years later), but it seems likely be that covert political machinations lay behind his removal. With many aspects of Thomson’s complex life, it is hard to disentangle fiction from fact.

Undaunted, Thomson resumed his writing career, and in 1925, he published Mr Pepper Investigates, a collection of humorous short mysteries, the most renowned of which is “The Vanishing of Mrs Fraser”. In the same year, he was arrested in Hyde Park for “committing an act in violation of public decency” with a young woman who gave her name as Thelma de Lava. Thomson protested his innocence, but in vain: his trial took place amid a blaze of publicity, and he was fined five pounds. Despite the fact that Thelma de Lava had pleaded guilty (her fine was reportedly paid by a photographer), Thomson launched an appeal, claiming that he was the victim of a conspiracy, but the court would have none of it. Was he framed, or the victim of entrapment? If so, was the reason connected with his past work in intelligence or crime solving? The answers remain uncertain, but Thomson’s equivocal responses to the police after being apprehended damaged his credibility.

Public humiliation of this kind would have broken a less formidable man, but Thomson, by now in his mid-sixties, proved astonishingly resilient. A couple of years after his trial, he was appointed to reorganise the Siamese police force, and he continued to produce novels. These included The Kidnapper (1933), which Dorothy L. Sayers described in a review for the Sunday Times as “not so much a detective story as a sprightly fantasia upon a detective theme.” She approved the fact that Thomson wrote “good English very amusingly”, and noted that “some of his characters have real charm.” Mr Pepper returned in The Kidnapper, but in the same year, Thomson introduced his most important character, a Scottish policeman called Richardson.

Thomson took advantage of his inside knowledge to portray a young detective climbing through the ranks at Scotland Yard. And Richardson’s rise is amazingly rapid: thanks to the fastest fast-tracking imaginable, he starts out as a police constable, and has become Chief Constable by the time of his seventh appearance – in a book published only four years after the first. We learn little about Richardson’s background beyond the fact that he comes of Scottish farming stock, but he is likeable as well as highly efficient, and his sixth case introduces him to his future wife. His inquiries take him – and other colleagues – not only to different parts of England but also across the Channel on more than one occasion: in The Case of the Dead Diplomat, all the action takes place in France. There is a zest about the stories, especially when compared with some of the crime novels being produced at around the same time, which is striking, especially given that all of them were written by a man in his seventies.

From the start of the series, Thomson takes care to show the team work necessitated by a criminal investigation. Richardson is a key connecting figure, but the importance of his colleagues’ efforts is never minimised in order to highlight his brilliance. In The Case of the Dead Diplomat, for instance, it is the trusty Sergeant Cooper who makes good use of his linguistic skills and flair for impersonation to trap the villains of the piece. Inspector Vincent takes centre stage in The Milliner’s Hat Mystery, with Richardson confined to the background. He is more prominent in A Murder is Arranged, but it is Inspector Dallas who does most of the leg-work.

Such a focus on police team-working is very familiar to present day crime fiction fans, but it was something fresh in the Thirties. Yet Thomson was not the first man with personal experience of police life to write crime fiction: Frank Froest, a legendary detective, made a considerable splash with his first novel, The Grell Mystery, published in 1913. Froest, though, was a career cop, schooled in “the university of life” without the benefit of higher education, who sought literary input from a journalist, George Dilnot, whereas Basil Thomson was a fluent and experienced writer whose light, brisk style is ideally suited to detective fiction, with its emphasis on entertainment. Like so many other detective novelists, his interest in “true crime” is occasionally apparent in his fiction, but although Who Killed Stella Pomeroy? opens with a murder scenario faintly reminiscent of the legendary Wallace case of 1930, the storyline soon veers off in a quite different direction.

Even before Richardson arrived on the scene, two accomplished detective novelists had created successful police series. Freeman Wills Crofts devised elaborate crimes (often involving ingenious alibis) for Inspector French to solve, and his books highlight the patience and meticulous work of the skilled police investigator. Henry Wade wrote increasingly ambitious novels, often featuring the Oxford-educated Inspector Poole, and exploring the tensions between police colleagues as well as their shared values. Thomson’s mysteries are less convoluted than Crofts’, and less sophisticated than Wade’s, but they make pleasant reading. This is, at least in part, thanks to little touches of detail that are unquestionably authentic – such as senior officers’ dread of newspaper criticism, as in The Dartmoor Enigma. No other crime writer, after all, has ever had such wide-ranging personal experience of prison management, intelligence work, the hierarchies of Scotland Yard, let alone a desperate personal fight, under the unforgiving glare of the media spotlight, to prove his innocence of a criminal charge sure to stain, if not destroy, his reputation.

Ingenuity was the hallmark of many of the finest detective novels written during “the Golden Age of murder” between the wars, and intricacy of plotting – at least judged by the standards of Agatha Christie, Anthony Berkeley, and John Dickson Carr – was not Thomson’s true speciality. That said, The Milliner’s Hat Mystery is remarkable for having inspired Ian Fleming, while he was working in intelligence during the Second World War, after Thomson’s death. In a memo to Rear Admiral John Godfrey, Fleming said: “The following suggestion is used in a book by Basil Thomson: a corpse dressed as an airman, with despatches in his pockets, could be dropped on the coast, supposedly from a parachute that has failed. I understand there is no difficulty in obtaining corpses at the Naval Hospital, but, of course, it would have to be a fresh one.” This clever idea became the basis for “Operation Mincemeat”, a plan to conceal the invasion of Italy from North Africa.

A further intriguing connection between Thomson and Fleming is that Thomson inscribed copies of at least two of the Richardson books to Kathleen Pettigrew, who was personal assistant to the Director of MI6, Stewart Menzies. She is widely regarded as the woman on whom Fleming based Miss Moneypenny, secretary to James Bond’s boss M – the Moneypenny character was originally called “Petty” Petteval. Possibly it was through her that Fleming came across Thomson’s book.

Thomson’s writing was of sufficiently high calibre to prompt Dorothy L. Sayers to heap praise on Richardson’s performance in his third case: “he puts in some of that excellent, sober, straightforward detective work which he so well knows how to do and follows the clue of a post-mark to the heart of a very plausible and proper mystery. I find him a most agreeable companion.” The acerbic American critics Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor also had a soft spot for Richardson, saying in A Catalogue of Crime that his investigations amount to “early police routine minus the contrived bickering, stomach ulcers, and pub-crawling with which later writers have masked poverty of invention and the dullness of repetitive questioning”.

Books in the Richardson series have been out of print and hard to find for decades, and their reappearance at affordable prices is as welcome as it is overdue. Now that Dean Street Press have republished all eight recorded entries in the Richardson case-book, twenty-first century readers are likely to find his company just as agreeable as Sayers did.

Martin Edwards

www.martinedwardsbooks.com

Chapter One

THE CHARWOMAN of the flat on the first floor came tearing down the back stairs into the milk-shop panting and breathless.

“Come quick, Mrs. Corder, there’s a terrible escape of gas upstairs. I just opened the door of my lady’s flat and the gas drove me back. I didn’t dare go in.”

“Oh, my God! And not a man about the place! I’ll come up with you. The first thing to do is to open the window and get the gas turned off. Come on; the shop’ll have to mind itself.”

Mrs. Corder caught up a towel as she went and the two women raced up the stairs. When they reached the top the smell of gas was overpowering, but Mrs. Corder held the towel over her mouth and ran to the door of the first floor flat. She was a woman of decision. She threw the door wide open and with her free hand flung back the shutters and threw up the window sash. Then she ran back into the passage to breathe.

“It’s coming from the kitchen from the gas-oven,” she gasped. “You stay here while I run in again and turn it off.”

With the towel pressed against her face she made a second plunge into the poisoned air and emerged white and shaking.

“I’ve got it turned off, but oh! My God! Miss Clynes is lying in there with her head in the gas- oven.”

“You don’t mean it? Whatever made her do that? I suppose I’d better go out and find a policeman.”

“No, you needn’t do that. I’ll ring up the police- station from the ’phone upstairs. You go and keep your eye on the shop a minute. Call me if I’m wanted.”

Three minutes later Mrs. Corder returned to her shop. “The gas isn’t so bad now. If we keep the shop door open the draught will blow it all out.”

“I can’t go up there by myself, Mrs. Corder; I wouldn’t have the nerve.”

“No one must go up there or touch anything until the police come. They’re sending round a plain clothes officer, and they say that they’ve ’phoned the police surgeon, so we can’t do any more till they come.”

“Are you sure she’s dead, Mrs. Corder?”

“She must be. No one could have lived through all that gas. Ah! Here’s John at last! He’ll go up.”

A rosy, broad-shouldered man rolled into the shop and stopped short. “Why, what’s up, Jenny? You look all scared.”

“Miss Clynes has been and gassed herself, Mr. Corder,” said the charwoman, who was beginning to enjoy herself, “and Mrs. Corder has been risking her life turning off the gas.”

“Go up, John, and make sure she’s quite dead. I’m sure I don’t know what you do to bring people round when they’ve been gassed.”

The husband turned to obey the order: she called after him, “Mind and not touch the body or anything else, more than you can help. The police are on their way down with the doctor. And you, Mrs. James; you mustn’t go away. The police will want to question us all.”

Annie James was thrilled to the marrow. “Will they? It’s the very first time I’ve been mixed up in a suicide.”

A heavy step was heard descending the stairs. John Corder, the roses faded from his cheeks, returned to the shop, shaking his head. “She’s dead all right, poor lady—stone cold.”

Two men darkened the shop door: the one a tall, broad-shouldered man approaching forty; the other a younger man with a professional air about him. He carried an attaché-case.

“Are you Mrs. Corder?” asked the first, addressing the mistress of the shop.

“Yes, sir.”

“You telephoned to the station that a woman had been gassed in this house.”

“That’s right, sir. It’s the lady that has the flat overhead. I suppose that you’re the police inspector?”

“No, I’m Detective Sergeant Hammett. The detective inspector is on leave. This gentleman is Dr. Wardell, the police surgeon. Will you kindly show us the way upstairs?”

“This way, gentlemen. Shall I go first to show you?” said John Corder, leading the way.

Mrs. James, the charwoman, in a spasm of curiosity, would have followed if Mrs. Corder had not held her back.

The three men seemed to fill the little kitchen.

“Can we have a little more light?” asked the doctor.

“Certainly, sir.” The dairyman switched on the electric light.

The doctor knelt down beside the body.

“We’ll leave you, doctor,” said the sergeant. “You’ll find us in the next room when you want us. Now, Mr. Corder, I want a few particulars from you.” They had moved into the bed-sitting-room. The sergeant looked round it and clicked his tongue. “Nicely furnished,” he said. “The poor lady knew how to make herself comfortable.”

“Oh, the furniture doesn’t belong to her. She was only a sub-tenant.”

The sergeant had taken out his notebook. “What was her name?”

“Miss Clynes; first name Naomi.”

“Her age?”

“I couldn’t tell you that. I should think by the look of her that she was between thirty and forty.

“How long had she been with you?”

“Let me see. It must be three months now.”

“Do you know the address of any of her friends?”

“No, Sergeant, I don’t. She was very reserved and we scarce ever saw her. You see, the flat has its own front door—37A Seymour Street—just round the corner, and she had no occasion to come into the shop.”

“But she must have had friends who called on her?”

“Funny you should say that. My wife was talking of that very thing less than a week ago—wondering whether she ever had any visitors.”

“Was she regular with her rent?”

“I can’t tell you that either. She took a sublease of the flat from Harding & Anstruther—the house-agents in Lower Sloane Street. It’s them that receive the rent and pay it over to the real tenant.”

“The real tenant?”

“Yes; you see we let the flat by the year to Mr. Guy Widdows, but he’s travelling abroad most of the time, and then the house-agents let his flat for him by the month. He’s out in Algeria now, and we forward his letters to him.”

“Was she employed anywhere? What did she do with her time?”

“Oh, she was an authoress, I believe, but her charwoman you saw downstairs might be able to tell you more about that.”

“I’ll see her presently. Now tell me, who was sleeping on the premises last night?”

“No one but my roundsman, Bob Willis. He sleeps in that little room at the back of the shop.”

“Where do you and your wife sleep?”

“We’ve got a room at 78 King’s Road.”

“Who has the floor above this?”

“It’s an office of some Jewish society, but no one sleeps there. A girl clerk goes up there once or twice a week to open their letters, but that’s all.”

“Have they got a latchkey to the door in Seymour Street?”

“Yes, they have, otherwise they would have to come through my shop.”

The doctor entered the room from the kitchen and addressed Sergeant Hammett. “It’s a clear case of gas-poisoning, Sergeant. If you’ll give me a hand we’ll carry the body into this room.”

“Very good, sir. Can you form any opinion about the hour when death took place?”

“Before midnight, I should say. At any rate the woman’s wrist-watch stopped at 5.10, so she hadn’t wound it up overnight.”

“There is no trace of violence?”

“Not a trace, except a slight bruise on one of her wrists, but she might have got that in knocking it against the kitchen range. I shall know more when we get the body down to the mortuary. Now, if you’ll come along.”

The three men carried the body reverently into the bed-sitting-room and laid it out on the divan-bed. Corder was sent downstairs for a sheet to cover it, and to call Annie James, the charwoman, to answer Sergeant Hammett’s questions.

“You’ll report; the case to the coroner, sir?” said Hammett, “and, if you are passing the police-station, perhaps you will give the word for them to send along the ambulance to take the body to the mortuary.”

“I will. I suppose that you’ll be able to tell the coroner’s officer when he comes where the woman’s relatives are to be found. The coroner is always fussy about that.”

“That’s the trouble, sir. Nobody here seems to know that she had any relatives, or for the matter of that, any friends. She had no visitors, they say. Perhaps you’ll mention this to the coroner when you ring him up. I’m going to inquire at the house-agent’s on my way to the station.”

“Then you are not going to search the flat?”

“No, doctor. I’m going to take a statement from the charwoman, and then I shall have to ask for help from Central. You see my inspector is away on leave, and I’ve more on my hands than I can do without this case.”

Annie James, the charwoman, knocked at the door. The doctor nodded good-bye to the sergeant and stumbled down the dark staircase. The woman entered the room timidly and shook with emotion at the sight of her late employer lying pallid and still on the couch.

“Please, sir, I’ve brought the sheet.”

“Then help me to cover her up.”

“Oh, pore thing! Pore thing! It’s awful to think of her being took like that, and that I shall never hear her voice again. So kind, she was, to me.”

“I want you to sit down there and answer my questions. Is your name Annie James?”

“That’s right, sir.”

“And you used to do charing here for this lady, Miss Clynes?”

“That’s right, sir. I got to know of her through an agency. She wanted a lady’s help, and of course, knowing me as they did, they said, ‘You couldn’t do better than take Mrs. James—that is, of course, if she’s free to oblige you, and…’”

“And she engaged you. How long ago was that?”

“Let’s see: it must have been eleven or twelve weeks ago. I know it was ...”

“Did you find her cheerful and happy?”

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say that, sir. She would pass the time of day with you, but she was never what you might call chatty. Very reserved and quiet I’d call her.”

“Did she ever talk to you about her friends?”

“No, sir, not a word. And another thing I thought funny. She never had anyone to tea—at least I never saw more than one cup and plate used in the flat. She seemed to spend all her time tapping on her typewriter. She was so busy at it that sometimes she didn’t seem to hear me when I spoke to her.”

“She had letters, I suppose?”

“Very few that I know of, sir. Sometimes I used to see an envelope or two in the dustbin.”

“Did she ever say what part of the country she came from?”

“No, sir. I did ask her once, but all I could get out of her was that she came somewhere from the north. She cut me quite short.”

“But she didn’t seem to you to be depressed—as if she had something on her mind?”

“No, sir. If she wasn’t talkative, it was just her way, I think. Some are born like that, aren’t they, sir?”

“And so it was a great surprise to you this morning to find that she had taken her own life?”

“Yes, sir. I can’t tell you what a shock it’s been.”

“Thank you, Mrs. James. I have your address in case we shall want you again.”

After calling on the house-agents in Lower Sloane Street, Sergeant Hammett took the Underground from Sloane Square to Westminster and sent in his name to the Chief Constable.

He was standing in the Central Hall when a gentleman of middle age, who appeared to be in a hurry, was stopped by the constable on duty and asked to fill up a printed form stating his name and his business.

“Nonsense! Everybody knows what my business is. I’m the coroner for the South Western district, and I want to see the Assistant Commissioner of the C.I.D. at once.”

“Then please put that on the form, sir.”

“This is quite new. I’ve never had to do this before.”

“Those are the Commissioner’s orders, sir. You can put on the form that you are in a hurry, sir.”

“Oh, well, if those are your orders—there, but please see that the form goes to Mr. Morden at once. I’ve no time to waste.”

The constable carried the form upstairs, and two minutes later returned with the Assistant Commissioner’s messenger. “Please step this way, sir.”

The coroner was conducted to a large room on the first floor where Charles Morden was sitting at his office table.

“You seem to be full of red tape since I was here last.”

Morden laughed. “Yes, it’s a new rule, but there is a useful side to it. What can I do for you?”

“My officer reported to me this morning that the Chelsea police had failed to find the address of any relations or friends of a woman who committed suicide last night by gassing herself. How can I hold an inquest with nothing but the medical evidence to go upon? It’s absurd! The woman must have had friends somewhere.”

“Let me see; the divisional detective inspector is away on leave, but the first-class sergeant ought to be working on the case.”

He rang the bell for his messenger. “Find out whether Sergeant Hammett from B Division is in the building,” he said. “Send him in if he is.”

In less than a minute Hammett was ushered into the room.

“This is the officer in charge of the inquiry,” said Morden to the coroner. “He will tell you how far he has got. The coroner wishes to know whether you have found any friends of the woman who gassed herself last night?”

“I’ve questioned everybody in the house, sir, and I think that they are telling the truth when they say that the woman received no visitors at her flat, and, as far as they know, received very few letters. I’ve called at the house-agents’, and there I’ve got a little further. She was required to furnish two references before entering into possession. I have their names and addresses here.” He took out his note-book. “A clergyman, the Vicar of St. Andrew’s, Liverpool, and a Mr. John Maze, a solicitor of Liverpool. Both references were satisfactory: both were shown to me.”

“Did you find any correspondence in her flat?”

“To tell you the truth, sir, I haven’t had time to search it yet. Our hands are pretty full with that big burglary in Tedworth Square, and that shopbreaking case in Lower Sloane Street, and I came on here to ask for help over this case.”

“Um! It seems, on the face of it, to be quite a simple case—one that the division ought to be able to clear up without calling in help from outside. Still—if you are really pressed—I’ll see what can be done.” He pressed a button on his table and picked up the receiver of his desk telephone.

“Is that you, Mr. Beckett? Is there an inspector free in Central to undertake a case?”

“…”

“Yes, he would do all right. Will you send him round?” Turning to Sergeant Hammett, he said,

“Inspector Richardson will take over the case. You’d better have a talk with him as you go out.”

The coroner rose. “I suppose,” he said, “that this inspector will get into touch with those people in Liverpool and let me know all that he finds out about the woman?”

“Yes, I’m sure he will.”

“He’s a good man?”

“About the best of the younger men; he’ll make a name for himself some day: he has had very quick promotion.”

Chapter Two

HAMMETT KNEW all about Inspector Richardson by repute. He was one of the first-class sergeants who imagined that they had a grievance against him because he had been promoted out of his turn, but Richardson was gradually overcoming this prejudice by his unfailing courtesy and good temper; indeed, very few of the malcontents bore him any ill will at this moment.

Hammett went to the inspectors’ room and found him packing up stationery and instruments in his attaché-case.

“Mr. Morden has put you in charge of a case in my division, Mr. Richardson. He wants me to tell you how far we’ve got up to date.”

“A case of suicide, Mr. Beckett said.”

“So far as the police surgeon could say after his first examination of the body, it was an ordinary case of gas-poisoning.”

“I fancy that you must be in a hurry to get back, Sergeant. We might take the Underground and talk as we go.”

They walked across to the Westminster Underground Station and took up their seats at the end of a car where they were free from possible eavesdroppers.

“You say that the dead woman had a servant?” asked Richardson.

“Only a charwoman who came in for a couple of hours in the morning.”

“Intelligent?”

“Too much so. She’s one of those women who don’t know how to stop talking until you pull them up. She’s enjoying herself over this suicide, I can tell you.”

“You say the deceased woman was an authoress?”

“So they told me at the milk-shop; at any rate she had a typewriter.” He said no more until they were approaching Seymour Street. “Here we are, Inspector. This is the door by which the tenants upstairs went in and out.”

The number—37A—was painted on the door. One stone step raised the floor from the street level. Richardson noticed that the step was whitened and that the keyhole and knocker on the green door were clean and polished, and so was the brass of the letter-box. There being no means of opening the door without the key, Hammett took Richardson round to the milk-shop and introduced him to the Corders.

“This is Inspector Richardson from New Scotland Yard, Mr. Corder. He’ll have to have the run of the flat for a day or two.”

“Very good, sir. While you were away the ambulance called and I helped the men to get the body down the stairs. There was quite a crowd outside to see it go off, and everyone stops to point out the house of the suicide, as they call it. It’s a bit unpleasant for us.”

“Oh, they’ll soon forget all about it; there’ll be some fresh attraction for them to-morrow. Now, Mr. Richardson, if you’ll follow me I’ll take you upstairs.”

They climbed the back stairs and reached the flat, Hammett briefly explaining the general layout of the house as they went. “You see, if it was a case of murder or even burglary, one might suspect that this office upstairs where the door is never locked was used as a hiding-place by the guilty person, who might have got in unobserved when the shop was empty for a minute, but the police surgeon seems satisfied that it was a clear case of suicide by gas-poisoning. I shall be curious to hear whether you find any relations or friends; it seems extraordinary that a woman in fairly easy circumstances should have no one in the world related to her.”

“I’ll let you know, and now as you’re a busy man, don’t trouble to wait any longer: I’ll get to work.”

Richardson had his own way of searching a room. He took off and folded his coat and turned up his sleeves to the elbows. Then he turned the key in the door. His first step was to go over the entire surface of the floor with a reading-glass: very carefully he moved out the divan from the wall and examined the surface of the cork linoleum that lay under it. Here he made his first discovery. Half hidden under the fringe of the Oriental carpet he found a cigarette of an expensive make. He was not himself a connoisseur of cigarettes, but he noted two points about this one—that it was gold-tipped and expensive-looking, and that when rolled gently between the finger and thumb the tobacco was not dry to the touch. This caused him to give a closer attention to the surface of the carpet than he would otherwise have done. Here again he was rewarded, for in front of an armchair a few inches from its right leg he came upon a little core of cigarette ash. Leaving it where it lay, he moved back the divan to its place against the wall and continued his search. His first concern was to ascertain whether there was a box of cigarettes in the room, or an ash-tray. He made a quick scrutiny of the cupboards and shelves. They had neither one nor the other. The deceased lady, he thought to himself, was no smoker, but this conclusion would have to be verified by the charwoman. He made a mental note of this and continued his search of the floor.

Failing to find anything noteworthy on the other part of the carpet, he continued his search on hands and knees into the little kitchen which opened out of the sitting-room. The light was not very good at this point; the floor of the kitchen was covered with a dark green cork linoleum, and as he crawled forward on his knees his trousers were caught by a nail, happily not so firmly as to tear the cloth. He turned and examined the spot under his reading-glass. He found that the edge of the cork, which had been securely nailed down with flat-headed tacks, had begun to crumble away, leaving one of the tacks to protrude above the surface. Here he made his third discovery. Caught under the head of the tack was a minute shred of dark green wool, of a darker shade even than that of the cork lino. Very gently he detached it from the nail, and opening the back of his watch case he slipped it in and snapped it down again. That was material for another inquiry that must be undertaken the same afternoon. Then he proceeded to make a search of the kitchen itself. It was scrupulously clean and neat, except for a few unwashed articles of crockery lying in the sink—the relics of the dead woman’s last meal. On the little kitchen table stood a coffee-pot and boiler combined, and one unwashed coffee-cup. There was an inch deep of cold coffee in the pot and the usual sediment that one finds in a coffee-cup. There was nothing unusual in any of these things, nor did he find anything suspicious in the bathroom beyond. He returned to the sitting-room.

His first care in this room was to open the typewriter, a portable Remington. Without touching the keys or the frame he pulled out of the carrier a half-written letter and read it eagerly.

“To all whom it may concern.

I, Naomi Clynes, have come by easy stages to believe that life is not worth living and that it is no crime to put an end to it. I am sorry for the trouble that I may be causing to a number of worthy people who have been kind to me, but I have neither kith nor kin dependent on me. I have as far as I know no creditors, but in case there are any such you will find in the corner of the drawer in this table a sum of £25 to pay the wages of my charwoman and any other debt that may be justly due. Out of the remainder the simplest possible funeral can be defrayed and the balance paid to Mr. Corder to whom my death may cause trouble.”

Richardson now embarked on a proceeding that would have puzzled people who did not know him. He brought his magnifying glass to bear on the spacing bar of the machine and took out from his attaché-case a wide-mouthed bottle of fine white powder. Dipping a camel-hair brush into this, he dusted the powder over the spacing bar and blew off the superfluity. Immediately fingerprints appeared on the black varnish with startling clearness.

Carefully replacing the unfinished letter in the machine, he opened the drawer and examined its contents. Besides the usual adjuncts of the typewriting outfit—rubber, oil-can, paper and carbon, he found £25 in Treasury notes, the sum mentioned in the unfinished letter. These he placed in an official envelope, labelled it and stuck it down. Then he ran downstairs to the milk-shop and asked Mrs. Corder to send Bob, the roundsman, to fetch Annie James, the charwoman, as quickly as possible, and also, if possible, the girl clerk to the Jewish organization on the floor above the flat. Then he returned upstairs to continue his search.

His first discovery on opening the wardrobe was a handbag of black leather. He turned out its contents on the table—a letter in its envelope, £1 17s. 3d. in silver and copper, and a latchkey. He ran downstairs to try it in the lock of No. 37A Seymour Street and found it fitted perfectly. He put it into his pocket for future use.

The letter also he annexed after running over its contents. It was from a firm of publishers—Stanwick & Co.—signed by a member of the firm, with a name he knew—“J. Milsom.” It was the last name in the list of the directors embossed on the left-hand corner of the firm’s notepaper. The letter was encouraging to a budding authoress. There was nothing in it to hint at professional disappointment.

The rest of the things in the wardrobe consisted of women’s clothing, hanging or neatly folded. He felt in every pocket in the garments, but found nothing of any interest. At the back of one of the shelves he came upon a pile of typed manuscript which he packed up to examine at his leisure.

A step sounded on the back stairs—a step which hesitated as it drew near the fatal room. It was Annie James, the charwoman, who stopped with her hand to her mouth when she saw the tall figure of the inspector. “I beg pardon, sir, I’m Miss Clynes’ help.”

“Oh yes; Annie James is your name, I think.”

“That’s right, sir.”

“Come in. I’ve really only one question to ask you. Did your late employer smoke?”

“No, sir, that I could swear to. No tobacco ever passed her lips.”

“I don’t mean to ask whether she was a confirmed and habitual smoker, but you know, Mrs. James, ladies do sometimes indulge in a cigarette. You yourself, for instance.”

“Never, sir. For one thing, when my brother gave me one and dared me to smoke it and put a match to it himself, my stomach rose and I was sick. That cured me of smoking for the rest of me life. I remember asking the poor lady once whether she had had the same experience as me, seeing that she didn’t smoke, but she told me that she thought it was a dirty habit for women to get into and made the room messy. And that’s why you won’t find an ash-tray about the place.”

“I suppose you gave the room a thorough clean at least once a week.”

“Oh, more than that, sir. When I clean a room, I clean it. No dirty corners. ‘Clean the corners and the middle takes care of itself’: that’s what I say.”