Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: e-artnow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

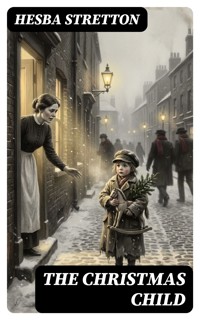

This carefully crafted ebook: "The Christmas Child (Illustrated)" is formatted for your eReader with a functional and detailed table of contents. Excerpt: "And now Christmas was coming. Joan had never kept Christmas, and knew nothing about it. But at Aunt Priscilla's farm it was a great day, as it always had been since she could remember. Every relative who could come to the farm was invited weeks beforehand; and nothing else was talked of but Christmas Day. The Sunday evening before it came old Nathan's sermon was all about the shepherds in the field, and how they found the little babe lying in the manger; and he told the story so well that Joan did not go to sleep at all, but sat listening to him with her dark eyes wide open." Hesba Stretton was the pen name of Sarah Smith (1832-1911), an English writer of children's books. Her moral tales and semi-religious stories, chiefly for the young, were printed in huge numbers. She became a regular contributor to Household Words and All the Year Round under Charles Dickens's editorship.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 49

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Christmas Child

(Illustrated)

Table of Contents

NATHAN LIGHTED HER STEPS

CHAPTER I THE COMING OF JOAN

Along some parts of the coast in South Wales the mountains rise abruptly from the shore, with only a narrow shingle between them and the sea.

High above the coast, however, there are warm, sunny little valleys and dells among the hills, where sheep can find pasture and a fold; and here there are many small farmsteads, surrounded by wild rocks and bleak uplands, where the farmer and his family live with their servants, if they happen to have any, as they used to do in old times, sitting in the same kitchen, and taking their meals together as one household.

Miss Priscilla Parry was the last of three leaseholders of one of these little farms. Her grandfather had enclosed the meadows and the corn-fields from the open mountain, on condition that he should have a lease for three lives from the owner of the land. His own and his son's had been two of the lives, and Priscilla's was the third.

The farm was poor, for the land was hard to cultivate. In every field there were places where the rocks pierced through the scanty soil, and stood out, grey and sharp, amid the grass and the ripening corn. The salt-laden winds and the fogs from the sea swept over them. Miss Priscilla spent no money in draining or manuring them; for was not the lease to pass away when she died, and she was nearly sixty years of age already?

But the sheep and the cows throve wonderfully on the short, sweet herbage they browsed on the mountains; and her butter and cheese, and the mutton she sold to the butchers, were known through all the country. Nobody could produce finer. Every one knew she was saving money up in her little mountain farmstead, and the money was being carefully laid by for Rhoda Parry, the niece she had adopted in her infancy and brought up as her own child.

Miss Priscilla was a spare, hard-featured woman, with a weather-stained face, and hands as horny as a man's with farm-work. Twice a week she wore a bonnet and shawl, when she went to market or church. All other times her head was covered by a cotton hood, which could not be damaged by rain, snow, or wind; and in bad weather she often went about her farm with an old sack over her shoulders. Her shoes were as thick and as heavily nailed as old Nathan's, her head servant, and she strode in and out of her sheds and stables and pigsties as if she had been a man. It was said she could get more work done for smaller wages than any farmer in the country.

There was not a prettier girl in all the parish, which was ten miles across, than Rhoda Parry, and she was always prettily and daintily dressed. She had her share of the work to do, but it was the easiest and most pleasant. If the weather was fine and clear, she might go to call the cattle home from their cool and breezy pasturage on the mountain side. The cows she had to milk were the gentle ones, that never kicked.

Aunt Priscilla did the churning of the cream, but Rhoda made the butter up into pretty golden pats, and wrapped them in cool, dark-green leaves. Rhoda tended the little flower patches in the garden, whilst her aunt saw to the vegetables. The light home-work, too, was Rhoda's; but the rough, laborious scrubbing and washing were done by her aunt and the only little maid they kept.

When Rhoda was about eighteen, another niece of Priscilla Parry's died in London, leaving one little girl quite unprovided for. All the other relatives decided that, as Priscilla was a single woman doing well in the world, it was clearly her duty to adopt the child, and without waiting for her consent, or her refusal, which was the more likely, they packed off little Joan to her great-aunt's farm.

The child was under six years of age, puny and pale and sickly, having lived most of her time in a close back room, up three pairs of stairs, in a London house of business, where her mother had been housekeeper. Her only playfellow had been a cat, and the prospect from her window had been the walls of the houses on the opposite side of a narrow court, and a mere streak of sky above them.

Miss Priscilla did not at all like to have another child thrown upon her. Her plans had been laid long ago, and to adopt Joan would quite upset them. She intended to make Rhoda independent, that she might have no temptation to marry for a home when her aunt died. Getting married, to Aunt Priscilla, usually meant the greatest misfortune that could befall a woman; and to guard Rhoda from it was the fixed purpose of her life.

Like Queen Elizabeth, she could not forgive anyone belonging to her, man or woman, who was foolish enough to marry. Her old man-servant, Nathan, had escaped this error, like herself; and both of them had lived free and single and wise, as Miss Priscilla Parry often said, even to their old age. Her cherished day-dream was that Rhoda would follow their example, and dwell with her in tranquillity and peace, until she herself closed her eyes, and fell asleep, in the course of twenty years or more, leaving Rhoda a staid, discreet, and unmarried woman of middle age.