1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Complete Poems" stands as a testament to the enduring power of verse, encapsulating the breadth of human emotion and experience. Esteemed for his lyrical style and masterful command of meter, Longfellow's work traverses themes of love, loss, and the profound beauty of nature. Written during a time when American literature was carving its own identity apart from European influences, the collection reflects the Romantic ideals prominent in the 19th century, echoing the sentiments of longing and reflection while employing an accessible yet evocative language, appealing to both common readers and scholars alike. Longfellow, an integral figure in American literature, was influenced by his extensive travels and deep engagement with both classical and contemporary literary traditions. His own experiences with personal loss and a commitment to social justice, particularly in relation to abolition, infuse his poetry with a distinctive voice that resonates with ethical and emotional depth. Longfellow's academic background, along with his dedication to fostering American culture, led him to produce works that not only entertain but also inspire and educate future generations. Readers seeking an enriching literary journey into the heart of human experience will find "The Complete Poems" essential. This collection offers profound insights into 19th-century America while remaining timeless in its exploration of the human condition. Longfellow's ability to weave poignant narratives with melodic rhythm invites both casual readers and literary enthusiasts to reflect, find solace, and derive meaning from his magnificent poetic tapestry. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The Complete Poems

Table of Contents

Introduction

This volume brings together the full poetic achievement of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, presenting his work as a coherent and evolving body rather than a handful of familiar pieces. It spans early lyrics and ballads, long narrative poems, verse dramas, sequences and sonnets, occasional and civic poems, and an extensive portfolio of translations. Organized largely according to the groupings in which the poems first appeared, the collection allows readers to follow the development of his voice and ambitions across five decades. Its purpose is both archival and experiential: to offer a reliable panorama of Longfellow’s artistry while enabling new connections among works often read in isolation.

The range of forms on display is unusually broad. Readers encounter intimate lyrics, descriptive nature pieces, and moral meditations from the earliest period; narrative ballads that adapt folk and maritime materials; and carefully constructed sonnets. The collection also includes longer narrative poems that function as verse epics, multi-part sequences arranged in thematic “flights,” and dramatic works written in verse. In addition, it features occasional poems composed for public moments, elegiac tributes, and commemorative pieces. A significant portion is devoted to translations from multiple languages and eras, underscoring Longfellow’s commitment to presenting world literature in accessible English meters and idioms.

The early poems and ballads establish Longfellow’s distinctive combination of musical cadence, moral purpose, and evocative scene-painting. Pieces such as the maritime narratives and portraits of craftspeople present ordinary courage and loss within memorable rhythms, often set against New England landscapes. Nature lyrics recast seasons, weather, and light as emblems of inner states, while reflective pieces explore patience, hope, and duty. Even at this stage, he pairs clarity of diction with carefully patterned sound, favoring steady beats and recurring motifs. These traits—clarity, musicality, and a humane moral gaze—become defining features of his subsequent work in more expansive forms.

Poems on social questions occupy a central place, most notably the sequence devoted to slavery. These pieces bring narrative and dramatic monologue to bear on a pressing national crisis, aiming for moral clarity rather than invective. The portraits of the enslaved and the reflections on conscience are concise, concrete, and accessible, aligning public rhetoric with personal witness. The sequence demonstrates Longfellow’s belief that poetry could participate responsibly in civic discourse, and that narrative empathy might reach readers whom argument alone could not. In blending lyric intensity with public appeal, he helped shape a model of American poetic engagement with reform.

Longfellow’s major narratives broaden his scope without abandoning his commitment to legible emotion and musical form. Evangeline unfolds against the Acadian expulsion, tracing fidelity and displacement in rolling classical measures. The Song of Hiawatha draws on Indigenous lore within a distinctive trochaic movement, shaping episodes into a unified cycle. The Courtship of Miles Standish reimagines early colonial New England with a blend of history and domestic sentiment in stately rhythms. Each poem creates a world whose meter matches its subject, demonstrating Longfellow’s interest in how form can carry cultural memory and lend dignity to communal and personal trials.

The Seaside and the Fireside brings public vision and private meditation into fruitful dialogue. Maritime pieces consider risk, solidarity, and human ingenuity, while domestic poems contemplate home, grief, and renewal. The volume’s architectural metaphors—ships, lighthouses, workshops—reflect a recurring fascination with craft and vocation. Here, Longfellow refines his ability to move from tangible objects and tasks to moral and emotional resonance, inviting readers to see everyday labor as a scene of meaning. The result is a poetry that honors both civic life and intimate experience, offering consolation without sentimentality and exhortation without rhetoric detached from lived particulars.

The Birds of Passage sequences, arranged in multiple flights, demonstrate how Longfellow used serial form to braid history, travel, memory, and meditation. Pieces on ports and battlefields sit beside songs of childhood and ruminations on aging, while reflections on landscapes and artifacts serve as prompts for ethical and historical inquiry. The sequence format permits a flexible architecture: brief lyrics, ballads, and occasional poems converse across distances of time and place. This mobility of perspective is a hallmark of his middle and later work, accommodating both the sudden insight of a single stanza and the cumulative force of recurring motifs.

Tales of a Wayside Inn extends his narrative reach through a convivial frame, situating storytellers in a Massachusetts setting that licenses wide thematic range. Within this gathering, legends, historical episodes, and Scandinavian sagas trade places with New England lore. The structure allows Longfellow to vary tone and meter while maintaining an overarching hospitality to sources and voices. Notable pieces from these gatherings have become touchstones of national memory, yet the full design matters: prologues, interludes, and finales create a rhythmic architecture that foregrounds community, conversation, and the transmission of stories across cultures and generations.

Later volumes intensify the elegiac and reflective strain while experimenting with form. The Masque of Pandora uses myth to consider curiosity, artifice, and unintended consequence, whereas The Hanging of the Crane finds domestic ritual worthy of epic attention. Morituri Salutamus offers a dignified meditation on aging, learning, and legacy. A Book of Sonnets collects tributes, portraits, and meditations that showcase his command of a compact, resonant architecture. Across these works, Longfellow’s voice grows more sparing and inward without losing its clarity, turning from public exhortation toward tempered recollection, gratitude, and the search for durable, humane values.

The dramatic works in verse—Christus: A Mystery, Judas Maccabaeus, and Michael Angelo—reveal Longfellow’s ambition to synthesize history, faith, and art within a reading drama. Christus assembles a triptych: scriptural episodes, a medieval legend of charity and devotion, and New England scenes of persecution and conscience. Judas Maccabaeus compresses crisis and liberation into choral and dialogic forms, while Michael Angelo uses monologue and scene to explore the disciplines of mastery, piety, and friendship. Though seldom staged, these works extend his narrative gifts into dramaturgy, testing how verse can embody debate, ritual, and revelation without sacrificing lyric poise.

A substantial section of translations affirms Longfellow’s cosmopolitan project. He renders selections from Spanish, Italian, French, German, and Scandinavian traditions; adapts Anglo-Saxon materials; and includes versions from Latin authors. These pages are not ancillary: they inform his diction, meter, and imagery throughout the original poems. By mediating diverse literatures into supple English verse, he cultivates a transatlantic and transhistorical conversation that grounds American poetry in wider inheritances. The translations balance fidelity to source with an ear for singable cadence, and they reinforce the collection’s broader vision of poetry as a meeting ground for languages, eras, and communities.

Across the whole, unifying themes emerge: the search for consolation amid loss; reverence for craft and conscience; the shaping force of memory and history; and the moral claims of community. Stylistically, Longfellow favors lucid syntax, steady rhythms, and audible patterning, often pairing vivid natural or artisanal images with reflective turns. His work remains significant because it made poetry a public art without abandoning intimacy, and because its hospitality to sources—local and global—helped define American literary culture. Read in this complete gathering, with narrative cycles, sequences, dramas, and translations side by side, his poems disclose a continuity of purpose and a remarkable versatility of means.

Author Biography

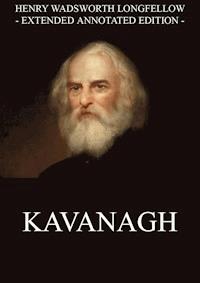

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was a central figure of nineteenth-century American literature, known for narrative poems, lyrical clarity, and translations that opened European traditions to U.S. readers. As a leading member of the so-called Fireside Poets, he helped make poetry a familiar presence in domestic life, shaping national tastes through accessible meters and memorable stories. He balanced Romantic sensibilities with American subjects, giving voice to history, legend, and everyday experience. Alongside his writing, he advanced the academic study of modern languages in the United States, teaching for years at Bowdoin College and Harvard University. His work became a cultural touchstone, widely recited and anthologized during his lifetime.

Longfellow grew up in coastal New England in the early 1800s and studied at Bowdoin College, where early skill with languages set the course for his career. After graduating, he began teaching and spent extended periods in Europe to deepen his command of French, Spanish, Italian, and German. Immersion in continental literatures exposed him to Romantic poetry and narrative models that would temper his American outlook with cosmopolitan breadth. He read medieval and Renaissance authors alongside modern voices, nurturing a lasting fascination with Dante. These experiences, coupled with the era's moral earnestness, informed an approach that valued clarity, musicality, and moral instruction without sacrificing narrative sweep.

Returning to the United States, Longfellow took up a professorship in modern languages, eventually joining Harvard. Early books reflected his transatlantic formation: Outre-Mer offered travel sketches, while Hyperion set a personal, reflective novel against German landscapes. Voices of the Night introduced lyrics that became widely known, including A Psalm of Life, with its exhortation to purposeful living. Ballads and Other Poems added memorable narrative pieces such as The Wreck of the Hesperus and The Village Blacksmith. These collections established his national reputation, demonstrating a gift for cadence and story that appealed to general audiences while remaining attentive to literary form.

By the mid-century, Longfellow turned to long narrative poems that aimed to craft an American epic imagination. Evangeline, written in classical hexameters, treated exile and perseverance through the Acadian story. The Song of Hiawatha, in trochaic tetrameter, drew on published Native American legends and ethnographic compilations, seeking a mythic register rooted in the continent's cultures; later readers have scrutinized its sources and representations. The Courtship of Miles Standish revisited colonial New England with brisk storytelling and historical color. These poems enjoyed broad readership, circulating in illustrated editions and public recitations, and they solidified his standing as the era's most popular American poet.

Longfellow's interest in national memory also shaped Tales of a Wayside Inn, a framed collection that includes Paul Revere's Ride, a poem that powerfully fixed a Revolutionary episode in the public imagination. He addressed civic conscience directly in Poems on Slavery, reflecting an antislavery stance in measured, persuasive verse. Meanwhile, his editorial and translation work, notably The Poets and Poetry of Europe, expanded access to continental traditions for American readers. Throughout, he favored clear diction, regular rhythms, and scenes of domestic or historical resonance, which made his books staples in households and schools and encouraged a culture of memorization and recitation.

In later decades, Longfellow experimented with verse drama and large narrative designs, including The Golden Legend and the broader project Christus: A Mystery, which wove religious themes across multiple parts. He devoted sustained effort to translating Dante's Divine Comedy in the late 1860s, aiming for close fidelity and extensive annotation, and he collaborated informally with fellow scholars while refining his version. Personal losses deepened the elegiac current in his later lyrics; sonnets such as The Cross of Snow, published posthumously, register quiet endurance and grief within classical forms. His scholarly and poetic labors increasingly converged, uniting moral reflection with technical discipline.

Longfellow lived and worked in Cambridge into the late nineteenth century, remaining a widely read figure until his death in the early 1880s. Posthumous recognition underscored his international reach, including a memorial bust in the mid-1880s in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey, the first time an American writer received that honor there. Though some twentieth-century critics deemed his verse conventional, later reassessments emphasize his craft, pedagogical influence, and the formative role he played in Americanizing European forms. His poems are still taught and quoted; familiar phrases have entered everyday speech. As a translator, teacher, and poet, he helped define a national literary inheritance.

Historical Context

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882) wrote across a century of American transformation, from the aftermath of the War of 1812 to the dawn of industrial modernity. His poems were shaped by a transatlantic Romanticism that mingled with the civic optimism of the young republic, a combination that made him the most widely read American poet of his day. The expansion of newspapers, magazines, and illustrated gift books created a mass audience for verse, while public lectures and parlor recitations popularized moral, historical, and domestic themes. Within this vibrant print culture, Longfellow’s lyric, narrative, dramatic, and translated works formed a shared cultural repertoire for schoolrooms and households across the United States.

Educated at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine (class of 1825), Longfellow moved early into a cosmopolitan orbit. His first European tour (1826–1829) took him through France, Spain, Italy, and Germany, where he studied at Göttingen and absorbed continental philology and Romantic aesthetics. Appointed to teach modern languages at Bowdoin in 1829, he then returned to Europe in 1835 en route to a new chair at Harvard. The dual identity of scholar-poet that emerged—linguist, translator, collector of ballads—shaped his entire career, grounding his American subjects in broader European literary forms and a meticulous attention to language, meter, and folklore.

After Mary Potter Longfellow’s death in Rotterdam in 1835, he settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1836 as professor of modern languages at Harvard. Cambridge placed him amid a nexus of reformist and literary energies stretching from Boston to Concord. He did not align fully with Emersonian Transcendentalism, yet he shared its ethical seriousness and fascination with the moral uses of poetry. The Craigie House on Brattle Street (Washington’s headquarters during the Revolution), which became the Longfellow home after his 1843 marriage to Fanny Appleton, was both domestic haven and salon, hosting writers, scholars, and reformers who helped define New England’s mid-century cultural authority.

Longfellow’s early collections crystalized an American idiom tuned to European models. Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841) harnessed the ballad revival, medievalism, and moral didacticism then flourishing in Britain and Germany. Their success coincided with the rise of Boston publishers like Ticknor and Fields and the later founding of the Atlantic Monthly in 1857, which sustained an audience for historical narratives, sea tales, and reflective lyrics. These volumes helped establish the Fireside Poets—Bryant, Holmes, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow—as a national canon whose poetry was memorized in graded schools, reprinted in newspapers, and recited at civic ceremonies.

His narrative imagination was historical, antiquarian, and comparative. He drew on Scandinavian sagas and chronicles (Heimskringla, Snorri Sturluson), German Volkslieder, and English antiquities to craft tales that relocated the old world’s heroics into New England landscapes. Antiquarian enthusiasm—fueled by philology, museum culture, and the translation boom—inflected poems about bells, bridges, towers, armories, and guild halls in Bruges, Nuremberg, and Florence, and also about supposed Norse traces on the New England coast. The effect is a poetics of continuity, in which medieval craft, civic virtue, and spiritual yearning resonate within a modern Atlantic civilization linked by trade, print, and memory.

New England history offered him paradigms of conscience, governance, and dissent. The Puritan legacy—Plymouth, Salem, Boston—provided material for poems and dramas exploring covenant, persecution, and the hazards of zeal. In the New England Tragedies (published 1868, later gathered in Christus, 1872), colonial episodes become moral case studies, aligning with his broader effort to locate American identity within a longer Anglo-Protestant and European tradition. The same historical impulse shaped narratives of Revolutionary alarm, provincial lore, and republican virtue, composed in an era when local commemorations, centennial pageantry, and historical societies were converting regional memory into national mythology.

Maritime New England and the global economy of the nineteenth century form a second, durable context. Shipbuilding, fisheries, coastal trade, and transoceanic routes linked Boston, Salem, and New Bedford to Liverpool, Havana, and Canton. Lighthouses, harbors, and shoals were not only scenery but social infrastructure, their hazards and heroism feeding ballads of wrecks and rescues. As steam power, clipper ships, and later telegraphy altered time and distance, Longfellow’s sea poems registered both the romance and the risk of technological acceleration. The sea also symbolized exile, migration, and return, themes that recur from brief lyrics to full-length narratives of separation and reunion.

Amid the intensifying national debate over slavery, Longfellow wrote Poems on Slavery (1842), a slender but influential book framed by friendship with the abolitionist senator Charles Sumner. Issued during northern antislavery mobilization and before the Mexican War and the Fugitive Slave Act, the volume addressed captivity, family rupture, and moral witness in accessible forms suited to parlors and lyceums. His antislavery sympathies surfaced elsewhere through historical analogies, elegies, and occasional poems, as the public sphere of Boston—lecterns, newspapers, courts, and State House steps—became a theater of conscience. The moral tone that made him a schoolroom favorite also positioned him within reformist print networks.

The Civil War reframed Longfellow’s historical imagination. He published poems of alarm, endurance, and bereavement that circulated widely in the Atlantic Monthly and newspapers. Naval battles, civic bells, and funeral processions became emblems of national trial. Personal grief deepened this register: in 1861 Fanny Appleton died after a fire at Craigie House; his burns and mourning suffuse later elegies and sonnets. While he did not travel to the front, he absorbed dispatches and public rituals, shaping verses that mingled private lament with civic hope. Reconstruction’s uncertainties echo in elegiac reflections on leadership, martyrdom, and the fragile peace of a republic remade by war.

Religion, broadly ecumenical, provided architecture for his career. Protestant by upbringing in Maine’s Congregational culture, he was drawn to Catholic ritual, medieval hagiography, and biblical narrative as symbolic resources rather than dogma. The Golden Legend (1851) recast a medieval miracle cycle; Christus (1872) assembled a triptych spanning Gospel scenes, a Rhineland legend, and New England history; occasional hymns and moral lyrics sought a common denominational language. Churches, cemeteries, and bells in his poems map a religious landscape where faith and art coexist. His cultivation of reverent, nonsectarian sentiment suited a pluralizing nation negotiating immigration, nativism, and the politics of worship.

The Song of Hiawatha (1855) attempted a national epic from Indigenous materials at a moment of removal, treaty violations, and frontier violence. Longfellow relied heavily on Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s ethnographic compilations and adopted trochaic meters modeled on the Finnish Kalevala to craft a cyclical, mythic narrative. The poem helped popularize Ojibwe and other Algonquian names in American letters, yet it also reflects mid-century romantic primitivism and the asymmetries of knowledge production between collectors and Native communities. Contemporary reception ranged from admiration to parody, while later criticism debates its appropriations alongside its role in widening non-Indigenous curiosity about Native languages and lore.

Evangeline (1847) exemplifies Longfellow’s sympathy for displaced communities within imperial histories. Drawing on a tale suggested by Nathaniel Hawthorne, he narrated the 1755 expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia, framing British colonial policy within a sentimental epic in dactylic hexameter. Its geography—from Grand Pré through the Ohio and Mississippi valleys to Louisiana—mapped an America being knit by canals, steamboats, and internal migration in the 1840s. Publication aligned with a broader culture of historical romance, from Cooper to Prescott, and with public debates over annexation, conquest, and the responsibilities of an emergent continental nation to peoples uprooted by war and policy.

Domesticity, childhood, and pedagogy anchored his moral authority. The common school movement, normal schools, and graded readers made poetry a vehicle of civic education in the 1840s and 1850s. Longfellow’s lyrics about home, labor, seasons, and parental grief were crafted for recitation and memorization, their meters and aphorisms fitting classroom routines and family gatherings. The sphere of the household—fireside, clock, spinning wheel—becomes ethical theater, where patience, diligence, and consolation are staged. His elegies for children, tributes to nurses and teachers, and verses on birthdays and holidays intersect with a nineteenth-century culture of sentiment that dignified private feeling as public virtue.

Industrialization and the crafts animated his poetics of work. Poems on armories, bridges, bells, and workshops juxtapose mass production with artisanal tradition, reflecting mid-century debates about technology, pacifism, and beauty. The Springfield Armory, New England mills, and European guild cities like Nuremberg and Bruges appear as case studies in the moral economy of labor. Keramos (1878) celebrates pottery as a world history of form and fire, linking Attic vases, Delftware, and East Asian glazes to New England clay. The Village Blacksmith stands as emblem for the dignity of manual skill amid the noise of progress, connecting domestic economy to civic independence.

Formally, Longfellow was an experimenter within accessibility. He popularized hexameter in English, adapted trochaic and ballad meters to American subjects, and revitalized the sonnet in an age that often preferred looser forms. His translations—Dante’s Divine Comedy (1867) foremost, but also Spanish romances, German ballads, Scandinavian sagas, and Anglo-Saxon excerpts—belong to a mid-century translation movement that fed the comparative study of literature in American colleges. The Boston-Cambridge circle’s Dante Club, including James Russell Lowell, Charles Eliot Norton, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, made medieval Italian poetry a civic instrument, aligning philological rigor with a republic’s claim to the full heritage of Europe.

Late career travel and honors affirmed his transatlantic stature. Journeys in 1868–1869 included visits with Alfred Tennyson and receptions in London and Rome; his bust was placed in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner in 1884, the first American so commemorated. Volumes such as The Masque of Pandora (1875), Keramos (1878), Ultima Thule (1880), and In the Harbor (1882) blend retrospection with cosmopolitan curiosity, returning to Mediterranean art, Northern sagas, and New England scenes. Personal loss remained a quiet undertow, surfacing in private sonnets circulated among friends and published posthumously. He died in Cambridge on 24 March 1882, by then a household name across the English-speaking world.

Longfellow’s legacy unfolded through school anthologies, civic commemorations, and popular memory. Critics in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sometimes faulted his sentiment and moral clarity as the modernist temper rose. Yet his works continued to structure American historical imagination—colonial origin stories, revolutionary alarms, maritime peril, and the migrations that populated the continent—while his translations, medievalism, and ethnographic borrowings shaped a cosmopolitan curriculum. The breadth of The Complete Poems reveals a project larger than any single volume: to braid languages, faiths, and crafts into a usable past for a democratic public, and to place the United States within an ongoing world literature.

Synopsis (Selection)

Hymn to the Night and companion early lyrics

A suite of meditative early poems seeking spiritual solace in night, stars, angels, and seasons. Signature pieces like A Psalm of Life urge purposeful living amid mortality.

Earlier Poems

Nature and patriotic pieces that paint New England landscapes and seasons while linking scenery to inner awakening and the poet’s vocation.

Ballads and Other Poems

Narrative ballads of legend and maritime peril alongside domestic and reflective lyrics, dramatizing courage, loss, craftsmanship, and aspiration.

Poems on Slavery

A moral sequence condemning American slavery through portraits, laments, and admonitions, appealing to conscience and national justice.

The Spanish Student

A romantic verse drama set in Spain about a noble student and the dancer Preciosa, whose concealed identity and courtly intrigues test loyalty, honor, and love.

The Belfry of Bruges and Other Poems

Travel-inspired lyrics and civic meditations that weave European history with American concerns, exploring memory, peace, art, and time in public and domestic spaces.

Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie

An episodic hexameter romance following an Acadian woman displaced by exile as she traverses North America in search of her betrothed, blending pastoral imagery with the pathos of separation.

The Seaside and the Fireside

Paired sequences that contrast the sea’s perilous, exploratory energy with the hearth’s reflective calm, celebrating discovery, shipbuilding, vocation, and resignation.

The Song of Hiawatha

An epic in trochaic meter drawing on Algonquian traditions to recount Hiawatha’s birth, deeds, love, leadership, and encounter with cultural change.

The Courtship of Miles Standish

A New England narrative centered on a love triangle among Miles Standish, John Alden, and Priscilla amid the Plymouth colony’s hardships, balancing martial duty with tender courtship.

Birds of Passage: Flight the First

A miscellany of lyrics on travel, history, memory, and moral reflection, treating movement and migration as metaphors for life’s transience and hope.

Birds of Passage: Flight the Second

A companion set on war, nature, toil, and childhood that balances national episodes with intimate moments, ranging from elegiac to buoyant.

Tales of a Wayside Inn (Parts I–III)

A framed storytelling cycle set at a Sudbury inn where guests trade verse tales from American and European legend and history, blending ballad, saga, and moral parable (e.g., Paul Revere’s Ride, The Saga of King Olaf).

Flower-de-Luce

Meditative and commemorative lyrics—war-time bells, tributes to Dante and Hawthorne, and reflections on art—linking mourning, faith, and the passage of time.

Birds of Passage: Flight the Third

Later lyrics that ponder illusion, memory, and public life in brief reflective forms, serving as interludes around the larger works of the period.

The Masque of Pandora

A mythic verse drama retelling Pandora’s creation and the release of human ills, counterpoised by the enduring presence of Hope, to explore curiosity, consequence, and redemption.

The Hanging of the Crane

A domestic chronicle of a household’s life—beginning with the hearth’s installation and unfolding through marriage and generations—treating the home as an emblem of continuity.

Morituri Salutamus

An occasional poem on aging, friendship, and the uses of culture, counseling perseverance and meaningful work in the evening of life.

A Book of Sonnets

A suite honoring poets and places and meditating on art, nature, and memory, using the sonnet’s compactness for portraits and aphoristic reflections.

Birds of Passage: Flight the Fourth

Travel and tribute poems from Europe and America—memorials to friends and landscapes—that consider history’s layers and personal pilgrimage.

Keramos

A narrative-meditative poem where the potter’s craft becomes both a tour of ceramic centers and a metaphor for shaping a temperate, durable life.

Birds of Passage: Flight the Fifth

Late-sequence lyrics mixing historical ballads, Eastern tales, personal elegies, and folk-style songs, with recurring themes of honor, exile, reconciliation, and the sea’s rhythms.

In the Harbor

Posthumous and late poems as a quiet farewell—calendar pieces, memorial elegies, coastal vignettes, and fragments like the unfinished Children’s Crusade—dwelling on memory and mortality.

Fragments

Unfinished passages and drafts that reveal subjects and forms Longfellow was shaping late in life.

Christus: A Mystery

A triptych of verse dramas tracing Christianity’s progress: The Divine Tragedy on Christ’s ministry and passion, The Golden Legend on medieval faith and charity, and The New England Tragedies on Puritan trials—linking sacred history to cultural conscience.

Judas Maccabaeus

A dramatic poem on the Jewish revolt against Seleucid rule, portraying Judas’s leadership and battles to restore worship and liberty.

Michael Angelo

A dramatic poem in scenes capturing Michelangelo’s late years—the tensions of art, faith, and patronage, and his bond with Vittoria Colonna—meditating on creation and renunciation.

Translations

Renderings from Spanish, Scandinavian, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Anglo-Saxon, Eastern, and Latin sources that bring ballads, lyrics, and classical and medieval texts into English, echoing themes of piety, love, fate, and craft.