1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

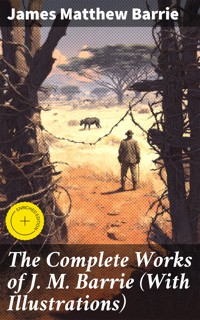

The Complete Works of J. M. Barrie (With Illustrations) presents a comprehensive collection of Barrie's literary oeuvre, showcasing his mastery of prose, drama, and the art of storytelling. Renowned for his whimsical yet profound exploration of childhood and the interplay between reality and imagination, Barrie's works, including the timeless classic Peter Pan, are imbued with rich symbolism and vibrant characters. This edition features illustrations that not only complement but enhance the text, providing readers with a multi-sensory engagement that reflects the Victorian and Edwardian literary context in which Barrie flourished. James Matthew Barrie, a Scottish author and playwright, was profoundly influenced by the loss of his brother at a young age, an event that ignited his fascination with youth and the concept of never growing up. His experiences in Edwardian society, coupled with his interactions with the Llewelyn Davies family, provided the emotional foundation that inspired his most famous works. Barrie's unique ability to blend humor with melancholy allowed him to create universally appealing narratives that resonate with readers across generations. For readers seeking a profound yet enchanting exploration of imagination and the complexities of childhood, this collection serves as an essential addition to any literary library. Barrie's whimsical prose and insightful commentary on the human experience make this volume not only a tribute to his genius but also a captivating read that will inspire and delight. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The Complete Works of J. M. Barrie (With Illustrations)

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection presents the complete creative range of James Matthew Barrie, gathering his full-length fiction, dramatic works, short stories and sketches, essays, and memoirs into a single, coherent library. By assembling the Peter Pan adventures alongside the Scottish novels, the celebrated comedies for the stage, and the reflective prose of the essays and autobiographical volumes, it aims to show the breadth of a writer whose imagination moved effortlessly between enchantment and everyday life. With illustrations enriching key texts, the set offers both newcomers and long-time readers a capacious overview of Barrie’s art, inviting sustained reading across genres and periods.

Readers will encounter multiple forms: novels of rural and urban life; novellas and shorter fiction; periodical sketches and story sequences; major plays and cycles of one-act plays; literary and cultural essays; and memoirs. Within these categories are distinct groupings—the Peter Pan corpus, the Thrums-related fiction, the comedies of manners, the wartime and domestic one-acts, appreciations of fellow writers and theatrical collaborators, and personal reminiscences. Rather than presenting a single mode, the collection emphasizes variety of voice and occasion while keeping Barrie’s sensibility in clear view. There are no letters or diaries here; the emphasis falls on published, authorial works.

The Peter Pan adventures form a cornerstone. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens frames the figure’s earliest appearances within a London park’s dreamlike spaces. Peter and Wendy offers the best-known narrative of the boy who would not grow up and the Darling children’s flight, while Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up preserves the theatrical design that first fixed these characters on stage. When Wendy Grew Up returns to their world in a brief, poignant afterpiece. Read together, these works reveal Barrie’s patterns of play, memory, and make-believe, contrasting nursery order with imaginative freedom and setting wonder against the quiet march of time.

Beyond Neverland stands a body of fiction concerned with community, vocation, and sentiment under pressure. Early books such as Auld Licht Idylls and A Window in Thrums depict small-town Scottish life with affectionate irony and close social observation. The Little Minister explores duty and desire in a village ministry. With Sentimental Tommy and Tommy and Grizel, Barrie follows a boy of artistic temperament into the ambiguities of ambition and love. The Little White Bird blends metropolitan scenes with visionary interludes. These narratives test dreams against responsibility, using humor to soften pathos, and favoring character and atmosphere over elaborate plot mechanics.

The range within the novels likewise stretches to satire and the uncanny. Better Dead turns a mischievous eye on public life and literary ambition, while When a Man’s Single follows the professional and social trials of a young man seeking his place. Farewell Miss Julie Logan embodies Barrie’s interest in the borderlands between pastoral quietude and unsettling experience. Across these works, the author’s prose privileges intimacy of address and swift tonal shifts. Familiar settings become slightly strange, and seemingly light episodes carry persistent questions about identity, reputation, and the costs of growing into or away from one’s early ideals.

The novellas and short stories preserve Barrie’s gift for the brief, suggestive scene. Collections such as A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches and Two of Them and Other Stories gather urban vignettes, domestic comedies, and whimsical conceits—narratives in which a hat, an umbrella, or a household routine suddenly acquires dramatic interest. Other Stories presents Scottish episodes and miniature studies of character. Many of these pieces first lived in periodicals, where their economy and warmth suited the column’s tight space. Read consecutively, they display a consistent tact: humor deflects cruelty, and sentiment is tempered by a lightly ironic narrator.

Within the shorter fiction, Barrie’s command of dialogue and ear for dialect are notable. The Courting of T’Nowhead’s Bell, Inconsiderate Waiter, and allied tales pivot on social encounter—courtship, service, neighborly obligation—rendered with close attention to speech rhythms and local custom. Sketches such as The Playwright and the Fowl and Reminiscences of an Umbrella demonstrate his playful anthropomorphism and theatrical turn of mind. Even when the subject seems trifling, the pieces reveal how performance governs ordinary life: people stage themselves for family, for community, and for the reader, while the narrator winks at the artifice without breaking the spell of companionship.

Barrie’s stage work spans genteel comedy, social fable, and delicate fantasy. Quality Street and What Every Woman Knows exemplify his civilized wit and respect for resourceful heroines. The Admirable Crichton dramatizes reversals of rank and the testing of conventions. Dear Brutus, A Kiss for Cinderella, and Mary Rose explore enchantment and the pull of memory, bringing theatrical transformations to intimate scale. The Professor’s Love Story, Alice Sit-by-the-Fire, and other plays exhibit deft pacing, playable roles, and exacting craft. Across these plays, disguise, role-playing, and second chances provide engines for action, while the staging marries ingenuity with emotional clarity.

Barrie also excelled in the one-act form. Half Hours contains Pantaloon, The Twelve-Pound Look, Rosalind, and The Will—compact plays that turn on quick reversals and character truth revealed in a single encounter. Echoes of the War gathers four short plays set against wartime realities, including The Old Lady Shows Her Medals, The New Word, Barbara’s Wedding, and A Well-Remembered Voice. These pieces favor intimate rooms over spectacle, rely on the resonance of unspoken feeling, and show Barrie’s readiness to address contemporary experience while retaining grace and tact. Their brevity sharpens his themes: dignity, courage, mischief, and the cost of absence.

The essays document a lifetime of reading, theatre-making, and public engagement. Charles Frohman: A Tribute reflects on a central producing partner; Preface to The Young Visiters introduces a singular child-authored novel; Captain Hook at Eton plays with the afterlife of a character on a ceremonial stage; and Courage distills moral exhortation with plain style. Literary appreciations such as The Humor of Dickens and The Lost Works of George Meredith show Barrie’s critical generosity. Pieces like Woman and the Press and A Plea for Smaller Books attest to an alertness to the practicalities of publishing, audience, and the uses of style.

The memoirs provide the most direct self-portrait. Margaret Ogilvy is an affectionate account of the author’s mother and the shaping force of family. The Greenwood Hat: Being a Memoir of James Anon 1885–1887 reconsiders an early period in his career, while An Edinburgh Eleven offers pencil portraits from student life and its milieu. My Lady Nicotine: A Study in Smoke humorously records bachelor quarters and habits with the air of shared confidences. In these volumes, Barrie writes as a companionable witness to his own formation, attentive to the play of memory, the quiet drama of kinship, and the craft of remembrance.

Taken together, these works illuminate a unified sensibility: a trust in play, a fascination with performance in everyday life, and a patient regard for the ordinary heart. Barrie’s lasting significance lies in his ability to set enchantment beside responsibility without reducing either—allowing imagination to enlarge, not escape, the world. The collection’s scope encourages readers to move between page and stage, city and village, fantasy and memoir, hearing the same voice adapt itself with tact and humor. As a complete resource, it invites return visits, renewed attention to lesser-known pieces, and a fuller appreciation of an enduring storyteller.

Author Biography

James Matthew Barrie (1860–1937) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, and playwright whose work bridged the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. He is best known as the creator of Peter Pan, a figure that reshaped modern conceptions of childhood, imagination, and theatrical fantasy. Barrie’s career moved fluidly between journalism, fiction, and the stage, and he became one of the most recognizable dramatists of his generation. His writing combined gentle irony with sentiment and a precise ear for dialogue, often probing the ties between memory and identity. Beyond a single iconic character, he produced a varied body of work that influenced popular theater and children’s literature.

Barrie was born in Kirriemuir, in Angus, Scotland, and educated in local schools before studying at the University of Edinburgh. As a young graduate in the early 1880s, he turned to journalism and learned the rhythms of deadline prose, a training that sharpened his dialogue and stagecraft. His early fiction drew on the speech and social textures of small-town Scottish life, notably in Auld Licht Idylls and A Window in Thrums. Critics praised the observation while noting a sentimental haze. These books established him with publishers and readers and opened doors in London’s literary world, where he began to imagine stories for the stage.

By the mid-1890s Barrie had become a bestselling novelist with The Little Minister, which he later dramatized. He increasingly favored the theater, finding in it a medium for light comedy edged with social curiosity. Working with prominent actors and producers, including the impresario Charles Frohman, he wrote plays that balanced whimsy and commentary. Quality Street and The Admirable Crichton exemplified his flair for role reversals, class masquerade, and poised, economical scenes. The stage sharpened his timing and invited technical experimentation, qualities that would culminate in his most famous creation. Meanwhile he continued to publish essays and sketches, refining a voice at once playful and reflective.

Peter Pan emerged from stories Barrie spun for the Llewelyn Davies family and took theatrical form in the early 1900s. The play Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, with its flying effects and nursery-to-Neverland transitions, startled audiences with its mixture of wonder and poignancy. Barrie later reworked the material in prose as Peter and Wendy, further exploring the costs and consolations of perpetual youth. The work became an annual favorite on British stages and a touchstone of children’s culture. Its blend of adventure, melancholy, and comic bravado broadened the possibilities of family theater and secured Barrie’s international fame.

In the decades that followed, Barrie alternated crowd-pleasing comedies with more haunted fables. What Every Woman Knows showcased an exact sense of character and politics; Dear Brutus and Mary Rose probed memory, regret, and second chances. His stature brought public roles and honors: he was created a baronet in the early 1910s and later appointed to the Order of Merit. He served in university life, including a rectorship at St Andrews in the late 1910s and, later, the chancellorship of the University of Edinburgh. These posts reflected his cultural authority and his interest in education and public service.

Barrie’s sensibility combined humor with a persistent inquiry into innocence, ambition, and loss. He published essays and sketches, among them My Lady Nicotine, and a memoir, Margaret Ogilvy, that illuminated the moral imagination behind his fiction. Publicly, he supported children’s health and cultural causes; most notably, he assigned the copyright of Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, allowing the work to generate continuing support for medical care. His addresses and occasional writings, including the celebrated rectorial lecture “Courage,” further revealed a belief in resilience tempered by doubt, a balance that shapes his stagecraft.

In his later years Barrie continued to revise and supervise revivals while encouraging younger dramatists. He died in London in the late 1930s, by then a figure synonymous with the enchantments and ambiguities of childhood on stage. His legacy rests not only on Peter Pan but on a repertoire that sustains regular revival for its deft construction and emotional finesse. Scholars read his work for its treatment of time, gender roles, and social play, while directors value its theatricality. The continuing association of Peter Pan with Great Ormond Street Hospital adds a philanthropic dimension to his reputation, keeping art and care in conversation.

Historical Context

James Matthew Barrie (1860–1937) wrote across the long transition from late Victorian to interwar Britain, and the historical currents of those decades flow through his complete works. Born in Kirriemuir, Angus, he moved to London in 1885, joining a metropolitan press and theatrical world newly energized by mass literacy, electric light, and modern publicity. His output—novels, sketches, plays, essays, and memoirs—reflects the era’s preoccupations with childhood, class, gender, empire, and memory. The Peter Pan adventures sit beside Kailyard-inflected Scottish fiction, West End comedies like Quality Street and What Every Woman Knows, wartime one-acts in Echoes of the War, and reflective memoirs such as Margaret Ogilvy and The Greenwood Hat.

Barrie’s Scottish upbringing anchored his early idiom. Kirriemuir—fictionalized as “Thrums” in Auld Licht Idylls and A Window in Thrums—preserved the pieties and social textures of nineteenth-century Presbyterian life shaped by the Disruption of 1843. The Kailyard movement of the 1890s, in which Barrie, S. R. Crockett, and Ian Maclaren were grouped by reviewers, modeled small-town speech, humor, and sentiment for a large English reading public. The Education (Scotland) Act of 1872 had broadened literacy, creating audiences for newspapers and single-volume novels. These conditions helped carry Barrie from provincial sketches to bestselling fiction like The Little Minister and to later plays that retained Scottish nuance within metropolitan forms.

University training at Edinburgh (M.A., 1882) and early provincial journalism prepared Barrie for London’s competitive press. He honed a compact, ironic sketch style in papers like the St. James’s Gazette, producing pieces later folded into collections such as A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches. The periodical market favored vignettes of domestic absurdity, whimsical addresses to readers, and quasi-reportage—modes Barrie also exploited in Two of Them and Other Stories and numerous occasional essays. His portraits in An Edinburgh Eleven show him as a literary observer of institutions and personalities, poised between a Scottish student culture and the booming capital’s “New Journalism,” which had widened the range of subjects and tones available to authors.

The 1890s publishing economy, pivoting from three-decker novels and circulating-library monopolies to single-volume editions and serial magazine rights, shaped Barrie’s career. Better Dead and When a Man’s Single appeared amid debates about respectable fiction, while Sentimental Tommy, Tommy and Grizel, and The Little White Bird capitalized on magazines’ appetite for serialized narratives with strong character psychology. Illustrated editions—central to this collection—also speak to a marketplace where pictures complemented text for middle-class buyers. Barrie’s short forms and novellas (A Tillyloss Scandal, Life in a Country Manse) demonstrate a flexible response to venues ranging from weekly papers to gift books, enabling him to move nimbly between Scottish realism, metropolitan comedy, and experimental fantasy.

Late Victorian and Edwardian theatre furnished Barrie with a second, increasingly dominant platform. The West End was governed by actor-managers and Lord Chamberlain’s censorship under the Theatres Act of 1843. The Ibsen debate—pitting “problem plays” against comic tradition—informed Barrie’s early parody Ibsen’s Ghost and his deft negotiation of moral scrutiny. London houses such as the Duke of York’s and producers alert to Christmas-season family fare favored romantic comedies set in carefully framed domestic spaces. Barrie’s stagecraft drew on the sentimental comedy line of Sheridan and Pinero while absorbing continental currents, allowing plays like The Professor’s Love Story, Quality Street, and What Every Woman Knows to balance wit, pathos, and social observation.

Charles Frohman, the American impresario who managed the Duke of York’s Theatre, became a decisive collaborator. He produced Peter Pan in London on 27 December 1904, with Gerald du Maurier as Mr. Darling/Captain Hook and Nina Boucicault as Peter, and transferred it to New York in 1905 with Maude Adams, ensuring the transatlantic fame of Barrie’s plays. Earlier, Frohman’s handling of The Little Minister in the 1890s had already demonstrated how Anglo-American touring could turn a Scottish village story into a theatrical spectacle. These networks tied Barrie’s work to the rhythms of West End and Broadway, the star system, and a managerial culture capable of staging ambitious illusions and seasonal revivals.

Technological and aesthetic changes in stagecraft facilitated Barrie’s blend of fantasy and domestic realism. The spread of electric lighting after the Savoy’s 1881 innovation, improved counterweight systems, and more sophisticated flying rigs enabled fairies to shimmer and boys to soar. Pantomime conventions, particularly the Christmas season appetite for transformation scenes, intersected with Barrie’s interest in the threshold between childhood and adulthood. Urban expansion made sites like Kensington Gardens emblematic; they were modern public spaces where middle-class families staged their own rituals. In plays and prose—Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, the Peter Pan play, and the novel Peter and Wendy—London’s parks became charged theatres of imagination within a rapidly mechanized city.

The cult of the child, rising in late-Victorian discourse through education reform, child-welfare activism, and new psychological inquiry, gave Barrie both subject and audience. His friendship with Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and her sons in the late 1890s and 1900s helped personalize these cultural currents, but the broader moment matters: readers and spectators prized childhood as a domain of innocence in an anxious empire. Barrie’s philanthropic bequest of Peter Pan royalties to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in 1929 institutionalized that association. The Peter Pan statue by Sir George Frampton, secretly erected in Kensington Gardens on 30 April 1912, confirmed the story’s place within London’s civic memory and its ongoing seasonal theatrical life.

Gender politics framed much of Barrie’s stage writing during the Edwardian era, when debates about the “New Woman,” suffrage (the WSPU formed in 1903), and marriage reform were current. What Every Woman Knows (1908) dramatises the unacknowledged labor and intelligence of women within public men’s success, while Quality Street plays with reputation, spinsterhood, and the social readmission of women after the Napoleonic wars—an historical lens for modern anxieties. In war-time plays like A Kiss for Cinderella, the figure of the self-sacrificing or resourceful woman intersects with nursing and relief work. Across essays and sketches, Barrie often observes the press’s treatment of women, aligning his comic gentleness with sharp commentary on domestic economics.

Class and service, fundamental to British society 1880–1914, are repeatedly reframed in Barrie’s comedies and stories. The Admirable Crichton satirizes rigid hierarchies by exalting competence over birth on a desert island, echoing late-imperial debates about merit and leadership. Sketches like Inconsiderate Waiter probe the rituals of London restaurants, while domestic pieces in Two of Them and Other Stories trace the boundaries between masters and servants. Scottish distinctiveness—visible in essays on Gretna Green’s marriage myth and in courtroom or kirk humor—locates law and custom within the Union’s diversity. Barrie’s gentle inversions kept his work acceptable to censors and fashionable audiences while holding up a mirror to Edwardian social choreography.

War altered Barrie’s tone and subjects. The South African War (1899–1902) unsettled imperial complacency, and the First World War (1914–1918) devastated families and the theatre world itself. Frohman’s death in the Lusitania sinking (7 May 1915) drew from Barrie an elegiac tribute and intensified his focus on memory and absence. Echoes of the War (including The Old Lady Shows Her Medals and The New Word) registers home-front grief, class crossings, and the new language war imposed on families. Dear Brutus (1917) and Mary Rose (1920) revisit choices, time, and haunting as postwar metaphors. The Boy David (1936) translates youthful heroism into a biblical key suited to anxious interwar audiences.

Barrie’s public standing shaped and was shaped by institutions. Created a baronet in 1913 and appointed to the Order of Merit in 1922, he served as Rector of the University of St Andrews (1919–1922), where he delivered the celebrated address “Courage” (3 May 1922). His presidency of the Society of Authors (late 1920s to his death) coincided with copyright debates and the professionalization of literary life. Essays such as Charles Frohman: A Tribute, The Humor of Dickens, The Lost Works of George Meredith, Q, and What is Scott’s Best Novel? locate him within an intergenerational conversation about national canons, stage producers, and the ethics of authorship amid expanding media.

Autobiographical writing provided Barrie with a method for integrating Scottish memory and literary vocation. Margaret Ogilvy (1896), his portrait of his mother, emerged after her death and crystallized his understanding of maternal faith, grief, and storytelling—motifs echoed in Tommy novels and in later plays of return. The Greenwood Hat: Being a Memoir of James Anon revisits his anonymous years in the London press, mapping the networks that carried sketches into books and plays. An Edinburgh Eleven offers campus-era portraits that double as a history of Scottish intellectual life. These memoirs illuminate the emotional ground of Peter Pan’s fixation on unaging boyhood and the gently ironic observer of London’s daily theatres.

Modern urban life—its clubs, omnibuses, restaurants, and fogs—gave Barrie a steady stream of comic material. My Lady Nicotine (1890) captures the sociability and rituals of smoking in an era when cigarettes and pipes punctuated male leisure and talk. Short sketches personifying influenza, umbrellas, and hats belong to a wider late-Victorian mode of light essay that thrived in magazines and on the feuilleton page. The “Russian flu” pandemic of 1889–1890 and later the “Spanish flu” shaped London’s rhythms and the humor used to domesticate anxiety. Across his short prose, the city appears as both constraint and stage, where small misadventures claim the dramatic attention once reserved for epic battles.

Censorship and convention made ingenuity a necessity. Under the Lord Chamberlain’s licensing regime, plays navigated propriety with allegory, double-casting, and the safety of fairyland. Peter Pan’s pairing of the father with Captain Hook let Barrie critique domestic authority while preserving a family bill. Pantomime traditions—women in breeches roles, transformation scenes, lavish finales—fortified his seasonal appeal and enabled technical experiments like wire-flying and quick-changes. “Half Hours” one-acts (Pantaloon, The Twelve-Pound Look, Rosalind, The Will) exploited small casts and compressed morals, fitting repertory programming and charity matinées. These forms allowed Barrie to test themes of marriage, money, performance, and identity under the watchful eye of official and audience guardians.

Adaptation and media proliferation supported Barrie’s long afterlife. The silent-film Peter Pan (1924) introduced the story to a global public; later sound versions, radio readings, and illustrated gift editions kept it current with new generations. Stage revivals of Quality Street, The Admirable Crichton, and What Every Woman Knows tracked changing fashions in costume drama and drawing-room comedy. His 1929 assignment of Peter Pan rights to Great Ormond Street Hospital linked art to pediatric care, ensuring periodic broadcasts and benefit performances. Essays such as Captain Hook at Eton and Preface to The Young Visiters show Barrie as sponsor and interpreter of youth culture, bridging elite schools, nursery rooms, and the professional stage.

Barrie’s oeuvre travels geographically and historically: from the kirkyards and kitchens of Angus to the gaslit streets of London and Broadway’s marquees; from the late-Victorian expansion of literacy and leisure to the shocks of mechanized war and interwar uncertainty. It speaks across the British Isles and the United States, drawing colonial and metropolitan audiences into a shared repertoire of sentiment, irony, and wonder. The recurring concerns—time’s arrest, class mobility, women’s intelligence, the ethics of leadership, the consolations of memory—mark books, stories, plays, essays, and memoirs alike. When he died in London on 19 June 1937, the institutions, readers, and theatres that had shaped him were already staging his legacy.

Synopsis (Selection)

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Origin tale of baby Peter who leaves his nursery for Kensington Gardens, befriending birds and fairies while touching on infancy, imagination, and separation.

Peter and Wendy

Novelization of the Peter Pan story: Peter escorts the Darling children to Neverland to battle pirates and play at eternal youth, poised between freedom and the pull to grow up.

Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up

The stage play of Peter’s adventures with the Darling children and Captain Hook, blending theatrical fantasy with bittersweet reflections on childhood.

When Wendy Grew Up

A brief sequel in which a grown Wendy meets Peter again, confronting memory, time, and the unchanging nature of his boyhood.

Better Dead

A satirical novella about a hapless student who joins a society dedicated to eliminating 'undesirables,' lampooning fads for moral reform and late-Victorian earnestness.

When a Man's Single

Comic novel of a young journalist’s rise and romantic entanglements across Scotland and London, weighing ambition against integrity and affection.

Auld Licht Idylls

Linked sketches of a stern Calvinist community in rural Scotland, tenderly observing its humor, discipline, and small-scale dramas.

A Window in Thrums

Vignettes from the weaving town of Thrums centered on Jess and her family, revealing quiet endurance, neighborhood bonds, and village lore.

The Little Minister

Romance of minister Gavin Dishart and the elusive Babbie, set amid class tensions and parish politics in a Scottish town.

Sentimental Tommy

Portrait of Tommy Sandys, an imaginative boy whose talent for invention complicates his moral growth and relationships.

Tommy and Grizel

Sequel tracing Tommy into adulthood and his troubled love for steadfast Grizel, where artistic vanity collides with emotional responsibility.

The Little White Bird

Episodic narrative about a solitary London bachelor and his attachment to a child, interwoven with the first appearance and origins of Peter Pan.

Farewell Miss Julie Logan

Atmospheric island novella in which a schoolmaster’s encounter with a mysterious girl blurs reality, longing, and local superstition.

A Tillyloss Scandal

Humorous Scottish tale of a village thrown into turmoil by a minor indiscretion, exposing gossip, pride, and communal mores.

Life in a Country Manse

Lightly satirical portrait of a minister’s household, charting domestic routines, parish expectations, and gentle hypocrisies.

Lady's Shoe

A delicate romantic episode sparked by a found shoe, exploring chivalry, misapprehension, and social convention.

A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches (group)

Playful essays and comic pieces that satirize everyday inconveniences and Victorian etiquette—idleness as an art, quack cures, schoolboy codes, mock-medical advice, and rules for living—delivered with mock-serious wit.

Two of Them and Other Stories (group)

Domestic and whimsical vignettes—from household upsets and anthropomorphic monologues to literary burlesques—that find comedy and pathos in small crises and private foibles.

Other Stories (group)

Scottish village tales, urban sketches, and parodies that poke at social pretenses and local custom, often turning on a sharp reversal or character-revealing dilemma.

Ibsen's Ghost

A parody of Ibsenite problem plays, exaggerating moral agendas and theatrical self-importance to comic effect.

Jane Annie

A light comic opera (with Arthur Conan Doyle) set at a girls’ school, where scheming and farcical romance collide.

Walker, London

A bustling farce of mistaken identities and social climbing in the metropolis, where a name becomes a passport to trouble.

The Professor's Love Story

Romantic comedy about an absent-minded academic who discovers he is in love, to the bewilderment of his household and colleagues.

The Little Minister: A Play

Stage adaptation of the novel, focusing the romance of Gavin Dishart and Babbie and the friction between duty and desire.

The Wedding Guest

A brief drawing-room comedy in which revelations and misunderstandings disrupt a wedding, testing manners and loyalties.

Little Mary

Sentimental comedy where a child’s innocence prompts adults to reconsider their pretenses, affections, and priorities.

Quality Street

Phoebe Throssel reinvents herself as a sparkling 'niece' to recapture a suitor’s regard, a witty critique of gender expectations and lost youth.

The Admirable Crichton

Shipwreck inverts an English household’s hierarchy as the capable butler Crichton becomes leader, exposing the contingency of class.

What Every Woman Knows

Maggie Wylie quietly engineers her ambitious husband’s success, a comedy probing male vanity and the undervalued intelligence of women.

Der Tag (The Tragic Man)

Wartime burlesque ridiculing Prussian militarism and brittle pride, turning grandiosity into farce.

Dear Brutus

A midsummer enchantment offers guests alternate lives they might have led, revealing character through the lure and limits of second chances.

Alice Sit-by-the-Fire

Domestic comedy in which a daughter’s melodramatic reading of her parents’ lives breeds misunderstandings before affection prevails.

A Kiss for Cinderella

Fairy-tale–inflected wartime piece about a poor London girl whose dream of a ball meets harsh realities and unexpected kindness.

Shall We Join the Ladies?

A parlor thriller where a host’s game to unmask a murderer plays with suspicion, guilt, and social poise.

Half an Hour

A tense one-act about a wife on the brink of elopement whose plans are upended, forcing a reckoning with duty and desire.

Seven Women

A cycle of brief plays presenting women at decisive moments—love, loyalty, sacrifice, and self-assertion—each hinging on a sharp moral choice.

Old Friends

A nostalgic one-act in which long-separated acquaintances revisit their past, finding humor and melancholy in memory.

Mary Rose

Eerie drama about a woman who vanishes on a Hebridean island and returns unchanged, a ghost story of time, loss, and home’s pull.

The Boy David

Dramatization of the biblical tale of David, Saul, and Jonathan, focusing on youthful destiny and the tragic costs of kingship.

Half Hours (Pantaloon; The Twelve-Pound Look; Rosalind; The Will)

Four concise plays: Pantaloon faces age with a clown’s dignity; The Twelve-Pound Look champions a woman’s financial independence; Rosalind portrays an actress negotiating illusion and truth; The Will probes friendship, marriage, and the ethics of inheritance.

Echoes of the War (The Old Lady Shows Her Medals; The New Word; Barbara's Wedding; A Well-Remembered Voice)

Four wartime one-acts: a charwoman 'adopts' a soldier and finds real kinship; a father and son face conscription-era candor; a wedding collides with military duty; a grieving family hears a message from a fallen airman.

Essays: Literary and Publishing (A Plea for Smaller Books; Boy's Books: Their Glorification; The Humor of Dickens; The Lost Works of George Meredith; Q; What is Scott's Best Novel?)

Critical and occasional pieces on reading, authorship, and the book trade, praising craft, poking fun at fashions, and weighing reputations from Dickens and Scott to Meredith and 'Q'.

Essays: Tributes and Addresses (Charles Frohman: A Tribute; Courage; Preface to The Young Visiters; Captain Hook at Eton; Neither Dorking Nor The Abbey)

Public addresses and prefaces commemorating colleagues, encouraging young audiences, and reflecting on fame and remembrance, often with affectionate playfulness toward Barrie’s own creations.

Essays: Journalism and Social Commentary (Woman and the Press; The Man from Nowhere; Ndintpile Pont(?))

Short journalistic sketches and satirical squibs on media, identity, and social roles, mixing light irony with observational wit.

Margaret Ogilvy

Intimate memoir of Barrie’s mother and their Scottish home, blending portraiture with reflections on family, faith, and a writer’s formation.

The Greenwood Hat: Being a Memoir of James Anon 1885-1887

Autobiographical chronicle of Barrie’s early London years under a pseudonym, tracing his apprenticeship in journalism and theater.

An Edinburgh Eleven: Pencil Portraits from College Life

Sketches of notable Edinburgh contemporaries and mentors, capturing student life and emerging literary networks with affectionate caricature.

My Lady Nicotine: A Study in Smoke

Comic reminiscences of bachelor life organized around pipe tobacco and a smoking-club camaraderie, gently satirizing habit and domesticity.

The Complete Works of J. M. Barrie (With Illustrations)

Peter Pan Adventures

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

The Kensington Gardens are in London, where the King lives.

Table of Contents

Map of Peter Pan's Kensington Gardens

I. The Grand Tour of the Gardens

You must see for yourselves that it will be difficult to follow Peter Pan's adventures unless you are familiar with the Kensington Gardens. They are in London, where the King lives, and I used to take David there nearly every day unless he was looking decidedly flushed. No child has ever been in the whole of the Gardens, because it is so soon time to turn back. The reason it is soon time to turn back is that, if you are as small as David, you sleep from twelve to one. If your mother was not so sure that you sleep from twelve to one, you could most likely see the whole of them.

The Gardens are bounded on one side by a never-ending line of omnibuses, over which your nurse has such authority that if she holds up her finger to any one of them it stops immediately. She then crosses with you in safety to the other side. There are more gates to the Gardens than one gate, but that is the one you go in at, and before you go in you speak to the lady with the balloons, who sits just outside. This is as near to being inside as she may venture, because, if she were to let go her hold of the railings for one moment, the balloons would lift her up, and she would be flown away. She sits very squat, for the balloons are always tugging at her, and the strain has given her quite a red face. Once she was a new one, because the old one had let go, and David was very sorry for the old one, but as she did let go, he wished he had been there to see.

The lady with the balloons, who sits just outside.

The Gardens are a tremendous big place, with millions and hundreds of trees; and first you come to the Figs, but you scorn to loiter there, for the Figs is the resort of superior little persons, who are forbidden to mix with the commonalty, and is so named, according to legend, because they dress in full fig. These dainty ones are themselves contemptuously called Figs by David and other heroes, and you have a key to the manners and customs of this dandiacal section of the Gardens when I tell you that cricket is called crickets here. Occasionally a rebel Fig climbs over the fence into the world, and such a one was Miss Mabel Grey, of whom I shall tell you when we come to Miss Mabel Grey's gate. She was the only really celebrated Fig.

We are now in the Broad Walk, and it is as much bigger than the other walks as your father is bigger than you. David wondered if it began little, and grew and grew, until it was quite grown up, and whether the other walks are its babies, and he drew a picture, which diverted him very much, of the Broad Walk giving a tiny walk an airing in a perambulator. In the Broad Walk you meet all the people who are worth knowing, and there is usually a grown-up with them to prevent them going on the damp grass, and to make them stand disgraced at the corner of a seat if they have been mad-dog or Mary-Annish. To be Mary-Annish is to behave like a girl, whimpering because nurse won't carry you, or simpering with your thumb in your mouth, and it is a hateful quality; but to be mad-dog is to kick out at everything, and there is some satisfaction in that.

If I were to point out all the notable places as we pass up the Broad Walk, it would be time to turn back before we reach them, and I simply wave my stick at Cecco Hewlett's Tree, that memorable spot where a boy called Cecco lost his penny, and, looking for it, found twopence. There has been a good deal of excavation going on there ever since. Farther up the walk is the little wooden house in which Marmaduke Perry hid. There is no more awful story of the Gardens than this of Marmaduke Perry, who had been Mary-Annish three days in succession, and was sentenced to appear in the Broad Walk dressed in his sister's clothes. He hid in the little wooden house, and refused to emerge until they brought him knickerbockers with pockets.

You now try to go to the Round Pond, but nurses hate it, because they are not really manly, and they make you look the other way, at the Big Penny and the Baby's Palace. She was the most celebrated baby of the Gardens, and lived in the palace all alone, with ever so many dolls, so people rang the bell, and up she got out of her bed, though it was past six o'clock, and she lighted a candle and opened the door in her nighty, and then they all cried with great rejoicings, 'Hail, Queen of England!' What puzzled David most was how she knew where the matches were kept. The Big Penny is a statue about her.

Next we come to the Hump, which is the part of the Broad Walk where all the big races are run; and even though you had no intention of running you do run when you come to the Hump, it is such a fascinating, slide-down kind of place. Often you stop when you have run about half-way down it, and then you are lost; but there is another little wooden house near here, called the Lost House, and so you tell the man that you are lost and then he finds you. It is glorious fun racing down the Hump, but you can't do it on windy days because then you are not there, but the fallen leaves do it instead of you. There is almost nothing that has such a keen sense of fun as a fallen leaf.

From the Hump we can see the gate that is called after Miss Mabel Grey, the Fig I promised to tell you about. There were always two nurses with her, or else one mother and one nurse, and for a long time she was a pattern-child who always coughed off the table and said, 'How do you do?' to the other Figs, and the only game she played at was flinging a ball gracefully and letting the nurse bring it back to her. Then one day she tired of it all and went mad-dog, and, first, to show that she really was mad-dog, she unloosened both her boot-laces and put out her tongue east, west, north, and south. She then flung her sash into a puddle and danced on it till dirty water was squirted over her frock, after which she climbed the fence and had a series of incredible adventures, one of the least of which was that she kicked off both her boots. At last she came to the gate that is now called after her, out of which she ran into streets David and I have never been in though we have heard them roaring, and still she ran on and would never again have been heard of had not her mother jumped into a 'bus and thus overtaken her. It all happened, I should say, long ago, and this is not the Mabel Grey whom David knows.

Returning up the Broad Walk we have on our right the Baby Walk, which is so full of perambulators that you could cross from side to side stepping on babies, but the nurses won't let you do it. From this walk a passage called Bunting's Thumb, because it is that length, leads into Picnic Street, where there are real kettles, and chestnut-blossom falls into your mug as you are drinking. Quite common children picnic here also, and the blossom falls into their mugs just the same.

Next comes St. Govor's Well, which was full of water when Malcolm the Bold fell into it. He was his mother's favourite, and he let her put her arm round his neck in public because she was a widow; but he was also partial to adventures, and liked to play with a chimney-sweep who had killed a good many bears. The sweep's name was Sooty, and one day, when they were playing near the well, Malcolm fell in and would have been drowned had not Sooty dived in and rescued him; and the water had washed Sooty clean, and he now stood revealed as Malcolm's long-lost father. So Malcolm would not let his mother put her arm round his neck any more.

Between the well and the Round Pond are the cricket pitches, and frequently the choosing of sides exhausts so much time that there is scarcely any cricket. Everybody wants to bat first, and as soon as he is out he bowls unless you are the better wrestler, and while you are wrestling with him the fielders have scattered to play at something else. The Gardens are noted for two kinds of cricket: boy cricket, which is real cricket with a bat, and girl cricket, which is with a racquet and the governess. Girls can't really play cricket, and when you are watching their futile efforts you make funny sounds at them. Nevertheless, there was a very disagreeable incident one day when some forward girls challenged David's team, and a disturbing creature called Angela Clare sent down so many yorkers that—However, instead of telling you the result of that regrettable match I shall pass on hurriedly to the Round Pond, which is the wheel that keeps all the Gardens going.

It is round because it is in the very middle of the Gardens, and when you are come to it you never want to go any farther. You can't be good all the time at the Round Pond, however much you try. You can be good in the Broad Walk all the time, but not at the Round Pond, and the reason is that you forget, and, when you remember, you are so wet that you may as well be wetter. There are men who sail boats on the Round Pond, such big boats that they bring them in barrows, and sometimes in perambulators, and then the baby has to walk. The bow-legged children in the Gardens are those who had to walk too soon because their father needed the perambulator.

You always want to have a yacht to sail on the Round Pond, and in the end your uncle gives you one; and to carry it to the pond the first day is splendid, also to talk about it to boys who have no uncle is splendid, but soon you like to leave it at home. For the sweetest craft that slips her moorings in the Round Pond is what is called a stick-boat, because she is rather like a stick until she is in the water and you are holding the string. Then as you walk round, pulling her, you see little men running about her deck, and sails rise magically and catch the breeze, and you put in on dirty nights at snug harbours which are unknown to the lordly yachts. Night passes in a twink, and again your rakish craft noses for the wind, whales spout, you glide over buried cities, and have brushes with pirates, and cast anchor on coral isles. You are a solitary boy while all this is taking place, for two boys together cannot adventure far upon the Round Pond, and though you may talk to yourself throughout the voyage, giving orders and executing them with despatch, you know not, when it is time to go home, where you have been or what swelled your sails; your treasure-trove is all locked away in your hold, so to speak, which will be opened, perhaps, by another little boy many years afterwards.

But those yachts have nothing in their hold. Does any one return to this haunt of his youth because of the yachts that used to sail it? Oh no. It is the stick-boat that is freighted with memories. The yachts are toys, their owner a fresh-water mariner; they can cross and recross a pond only while the stick-boat goes to sea. You yachtsmen with your wands, who think we are all there to gaze on you, your ships are only accidents of this place, and were they all to be boarded and sunk by the ducks, the real business of the Round Pond would be carried on as usual.

Paths from everywhere crowd like children to the pond. Some of them are ordinary paths, which have a rail on each side, and are made by men with their coats off, but others are vagrants, wide at one spot, and at another so narrow that you can stand astride them. They are called Paths that have Made Themselves, and David did wish he could see them doing it. But, like all the most wonderful things that happen in the Gardens, it is done, we concluded, at night after the gates are closed. We have also decided that the paths make themselves because it is their only chance of getting to the Round Pond.

One of these gypsy paths comes from the place where the sheep get their hair cut. When David shed his curls at the hair-dressers, I am told, he said good-bye to them without a tremor, though his mother has never been quite the same bright creature since; so he despises the sheep as they run from their shearer, and calls out tauntingly, 'Cowardy, cowardy custard!' But when the man grips them between his legs David shakes a fist at him for using such big scissors. Another startling moment is when the man turns back the grimy wool from the sheeps' shoulders and they look suddenly like ladies in the stalls of a theatre. The sheep are so frightened by the shearing that it makes them quite white and thin, and as soon as they are set free they begin to nibble the grass at once, quite anxiously, as if they feared that they would never be worth eating. David wonders whether they know each other, now that they are so different, and if it makes them fight with the wrong ones. They are great fighters, and thus so unlike country sheep that every year they give my St. Bernard dog, Porthos, a shock. He can make a field of country sheep fly by merely announcing his approach, but these town sheep come toward him with no promise of gentle entertainment, and then a light from last year breaks upon Porthos. He cannot with dignity retreat, but he stops and looks about him as if lost in admiration of the scenery, and presently he strolls away with a fine indifference and a glint at me from the corner of his eye.

The Serpentine begins near here. It is a lovely lake, and there is a drowned forest at the bottom of it. If you peer over the edge you can see the trees all growing upside down, and they say that at night there are also drowned stars in it. If so, Peter Pan sees them when he is sailing across the lake in the Thrush's Nest. A small part only of the Serpentine is in the Gardens, for soon it passes beneath a bridge to far away where the island is on which all the birds are born that become baby boys and girls. No one who is human, except Peter Pan (and he is only half human), can land on the island, but you may write what you want (boy or girl, dark or fair) on a piece of paper, and then twist it into the shape of a boat and slip it into the water, and it reaches Peter Pan's island after dark.

We are on the way home now, though of course, it is all pretence that we can go to so many of the places in one day. I should have had to be carrying David long ago, and resting on every seat like old Mr. Salford. That was what we called him, because he always talked to us of a lovely place called Salford where he had been born. He was a crab-apple of an old gentleman who wandered all day in the Gardens from seat to seat trying to fall in with somebody who was acquainted with the town of Salford, and when we had known him for a year or more we actually did meet another aged solitary who had once spent Saturday to Monday in Salford. He was meek and timid, and carried his address inside his hat, and whatever part of London he was in search of he always went to Westminster Abbey first as a starting-point. Him we carried in triumph to our other friend, with the story of that Saturday to Monday, and never shall I forget the gloating joy with which Mr. Salford leapt at him. They have been cronies ever since, and I noticed that Mr. Salford, who naturally does most of the talking, keeps tight grip of the other old man's coat.

Old Mr. Salford was a crab-apple of an old gentleman who wandered all day in the Gardens.

The two last places before you come to our gate are the Dog's Cemetery and the chaffinches nest, but we pretend not to know what the Dog's Cemetery is, as Porthos is always with us. The nest is very sad. It is quite white, and the way we found it was wonderful. We were having another look among the bushes for David's lost worsted ball, and instead of the ball we found a lovely nest made of the worsted, and containing four eggs, with scratches on them very like David's handwriting, so we think they must have been the mother's love-letters to the little ones inside. Every day we were in the Gardens we paid a call at the nest, taking care that no cruel boy should see us, and we dropped crumbs, and soon the bird knew us as friends, and sat in the nest looking at us kindly with her shoulders hunched up. But one day when we went there were only two eggs in the nest, and the next time there were none. The saddest part of it was that the poor little chaffinch fluttered about the bushes, looking so reproachfully at us that we knew she thought we had done it; and though David tried to explain to her, it was so long since he had spoken the bird language that I fear she did not understand. He and I left the Gardens that day with our knuckles in our eyes.

II. Peter Pan

If you ask your mother whether she knew about Peter Pan when she was a little girl, she will say, 'Why, of course I did, child'; and if you ask her whether he rode on a goat in those days, she will say, 'What a foolish question to ask; certainly he did.' Then if you ask your grandmother whether she knew about Peter Pan when she was a girl, she also says, 'Why, of course I did, child,' but if you ask her whether he rode on a goat in those days, she says she never heard of his having a goat. Perhaps she has forgotten, just as she sometimes forgets your name and calls you Mildred, which is your mother's name. Still, she could hardly forget such an important thing as the goat. Therefore there was no goat when your grandmother was a little girl. This shows that, in telling the story of Peter Pan, to begin with the goat (as most people do) is as silly as to put on your jacket before your vest.

Of course, it also shows that Peter is ever so old, but he is really always the same age, so that does not matter in the least. His age is one week, and though he was born so long ago he has never had a birthday, nor is there the slightest chance of his ever having one. The reason is that he escaped from being a human when he was seven days old; he escaped by the window and flew back to the Kensington Gardens.

If you think he was the only baby who ever wanted to escape, it shows how completely you have forgotten your own young days. When David heard this story first he was quite certain that he had never tried to escape, but I told him to think back hard, pressing his hands to his temples, and when he had done this hard, and even harder, he distinctly remembered a youthful desire to return to the tree-tops, and with that memory came others, as that he had lain in bed planning to escape as soon as his mother was asleep, and how she had once caught him half-way up the chimney. All children could have such recollections if they would press their hands hard to their temples, for, having been birds before they were human, they are naturally a little wild during the first few weeks, and very itchy at the shoulders, where their wings used to be. So David tells me.

I ought to mention here that the following is our way with a story: First I tell it to him, and then he tells it to me, the understanding being that it is quite a different story; and then I retell it with his additions, and so we go on until no one could say whether it is more his story or mine. In this story of Peter Pan, for instance, the bald narrative and most of the moral reflections are mine, though not all, for this boy can be a stern moralist; but the interesting bits about the ways and customs of babies in the bird-stage are mostly reminiscences of David's, recalled by pressing his hands to his temples and thinking hard.

Well, Peter Pan got out by the window, which had no bars. Standing on the ledge he could see trees far away, which were doubtless the Kensington Gardens, and the moment he saw them he entirely forgot that he was now a little boy in a nightgown, and away he flew, right over the houses to the Gardens. It is wonderful that he could fly without wings, but the place itched tremendously, and—and—perhaps we could all fly if we were as dead-confident-sure of our capacity to do it as was bold Peter Pan that evening.

He alighted gaily on the open sward, between the Baby's Palace and the Serpentine, and the first thing he did was to lie on his back and kick. He was quite unaware already that he had ever been human, and thought he was a bird, even in appearance, just the same as in his early days, and when he tried to catch a fly he did not understand that the reason he missed it was because he had attempted to seize it with his hand, which, of course, a bird never does. He saw, however, that it must be past Lock-out Time, for there were a good many fairies about, all too busy to notice him; they were getting breakfast ready, milking their cows, drawing water, and so on, and the sight of the water-pails made him thirsty, so he flew over to the Round Pond to have a drink. He stooped and dipped his beak in the pond; he thought it was his beak, but, of course, it was only his nose, and therefore, very little water came up, and that not so refreshing as usual, so next he tried a puddle, and he fell flop into it. When a real bird falls in flop, he spreads out his feathers and pecks them dry, but Peter could not remember what was the thing to do, and he decided rather sulkily to go to sleep on the weeping-beech in the Baby Walk.

At first he found some difficulty in balancing himself on a branch, but presently he remembered the way, and fell asleep. He awoke long before morning, shivering, and saying to himself, 'I never was out on such a cold night'; he had really been out on colder nights when he was a bird, but, of course, as everybody knows, what seems a warm night to a bird is a cold night to a boy in a nightgown. Peter also felt strangely uncomfortable, as if his head was stuffy; he heard loud noises that made him look round sharply, though they were really himself sneezing. There was something he wanted very much, but, though he knew he wanted it, he could not think what it was. What he wanted so much was his mother to blow his nose, but that never struck him, so he decided to appeal to the fairies for enlightenment. They are reputed to know a good deal.

There were two of them strolling along the Baby Walk, with their arms round each other's waists, and he hopped down to address them. The fairies have their tiffs with the birds, but they usually give a civil answer to a civil question, and he was quite angry when these two ran away the moment they saw him. Another was lolling on a garden chair, reading a postage-stamp which some human had let fall, and when he heard Peter's voice he popped in alarm behind a tulip.

When he heard Peter's voice he popped in alarm behind a tulip.