0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In "The Complete Works of Stephen Crane," readers are offered an unrivaled journey through the innovative mind of one of American literature's most groundbreaking figures. This comprehensive collection showcases Crane's mastery of realism and naturalism, with renowned works such as "The Red Badge of Courage" and poignant short stories that capture the essence of human struggle and existential angst. Crane's distinctive literary style'—characterized by vivid imagery, psychological depth, and a minimalist approach'—transports readers to the tumultuous landscapes of war, urban life, and deep personal conflict, reflecting the societal changes of the late 19th century. Stephen Crane, born in 1871, experienced a diverse yet tumultuous life, serving as a war correspondent and being deeply influenced by his observations of human suffering and resilience. His exposure to the Civil War's aftermath and his disdain for romanticism led him to explore themes of survival, isolation, and the human condition. Crane's experiences shaped his unique narrative voice and crafted a literary legacy that challenges readers' perceptions of courage, fate, and the impact of environment on individual lives. This authoritative collection is essential for any reader seeking to delve into the rich tapestry of human experience. "The Complete Works of Stephen Crane" invites both scholars and casual readers alike to engage with the powerful themes of uncertainty and moral ambiguity, solidifying Crane's status as a pivotal figure in American literature. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The Complete Works of Stephen Crane

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection presents the full arc of Stephen Crane’s imaginative achievement, bringing together the novels, novellas, story cycles, and poetry that define his place in American literature. Organized to showcase range as well as continuity, it allows readers to follow Crane’s development from urban naturalism to psychological war writing, from ironic comedy to stark lyricism. The purpose is not merely to assemble titles, but to trace a singular artistic temperament confronting modern experience—violence and fear, social pressure and courage, illusion and perception. Read as a whole, the works illuminate one another, revealing Crane’s distinctive voice in multiple modes and across varied settings.

The scope encompasses long and short fiction alongside verse. The novels and novellas include The Red Badge of Courage, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, George’s Mother, The Third Violet, Active Service, The Monster, and The O’Ruddy. The story collections span The Little Regiment and Other Episodes from the American Civil War, The Open Boat and Other Stories, Blue Hotel & His New Mittens, Whilomville Stories, Wounds in the Rain: War Stories, Great Battles of the World, and Last Words. The poetry is gathered in The Black Riders and Other Lines and War is Kind. Together these genres display Crane’s compact, versatile art.

Across this body of work, several ties bind. Crane’s prose often marries naturalistic pressure with impressionistic surface: swift, vivid images, abrupt transitions, and a focus on sensation rather than explanation. He is fascinated by the split between inner feeling and outer event—how fear, honor, shame, and desire refract action. War, urban poverty, small-town conformity, and the conflict between individual will and impersonal forces recur. His poetry distills the same concerns into brief, paradoxical statements and stark imagery. The result is a literature of intensity and economy, where moral questions emerge not as pronouncements but as tests enacted under stress.

The Red Badge of Courage stands as a landmark of psychological realism, reframing the American Civil War through the perceptions of a young volunteer. Rather than unfolding through grand strategy, the novel dwells on uncertainty, rumor, and the immediacy of fear and resolve. Crane’s compressed scenes, shifting light, and color-charged language create a battlefield of mind as much as ground. Its influence on later war writing is profound, yet within this collection it also converses with his other depictions of conflict, showing how courage and self-knowledge come less from doctrine than from experience pressed to its limits.

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and George’s Mother anchor Crane’s urban realism. Set amid tenement life, they examine the coercive force of environment—crowded rooms, public judgment, precarious work—and the fragile hopes that rise against it. Without indulging sentimentality, Crane attends to moments of aspiration and tenderness while tracking the contours of humiliation and social stigma. The narrative restraint, close attention to gestures, and eye for spectacle and street ritual anticipate later documentary fiction. Read beside the war narratives, these books underscore Crane’s constant theme: the individual’s effort to assert dignity within systems that confuse, misread, or crush intent.

The Third Violet and Active Service broaden Crane’s palette. The Third Violet portrays artists and aspirants navigating reputation, romance, and the marketplace, filtering comedy and critique through quick, theatrical episodes. Active Service turns to the pressure of a contemporary conflict on private lives, considering how war’s spectacle entangles curiosity, ambition, and moral stance. In each, Crane tests social performance—how people act when they know they are being watched—and the uneasy mix of bravado and vulnerability. Stylistically, the prose remains spare and rhythmic, attentive to posture and glance, and to the small misunderstandings that drive events toward crisis.

The Monster and The O’Ruddy show Crane in contrasting registers. The Monster, set in a small town associated with his Whilomville cycle, explores communal fear, gratitude, and scapegoating after a shocking incident upends local arrangements. It weighs sympathy against reputation, placing ethical choice under the cold light of public scrutiny. The O’Ruddy, by contrast, offers a spirited romance; begun by Crane and published with completion by Robert Barr after Crane’s death, it displays his wit and pacing in a more buoyant key. Together they demonstrate his flexibility, from moral parable to adventure, without abandoning his incisive social eye.

The Little Regiment and Other Episodes from the American Civil War extends the concerns of The Red Badge of Courage into compact narratives. The focus remains on ordinary soldiers, the friction of rumor and noise, and the jagged rhythms of engagement. Crane’s technique favors partial views, cut by smoke, weather, and fatigue, yielding a mosaic of moments rather than a panoramic chronicle. This approach keeps analysis close to sensation: the weight of equipment, the glare of a field, the suddenness with which caution becomes action. The collection deepens his study of comradeship, rivalry, and the uneasy bonds forged under fire.

The Open Boat and Other Stories gathers some of Crane’s most enduring short fiction. The title story, informed by his experience as a shipwreck survivor, renders the sea as an immense, impersonal presence, and human cooperation as both necessary and fragile. Across the volume, settings vary, but the method persists: clean lines, swift dialogue, and a refusal to explain beyond what characters can know. The reader is asked to infer motive and meaning from gesture and pattern. Nature’s indifference, the limits of perception, and the demands of endurance form a quiet thread that binds disparate tales into a whole.

Blue Hotel & His New Mittens, Whilomville Stories, and Wounds in the Rain: War Stories reveal Crane’s breadth. The Blue Hotel dissects misperception and performance amid menace; His New Mittens turns to childhood with comic precision; Whilomville Stories maps small-town life with sympathy and bite. In Wounds in the Rain, Crane draws on his work as a war correspondent to create fictions marked by immediacy and moral unease. Across these books, he shifts scale—domestic, frontier, battlefield—while maintaining economy of means. The throughline is his alertness to how people improvise under stress, misread one another, and occasionally rise to grace.

Great Battles of the World and Last Words occupy the borderlands between fiction and other narrative forms. Great Battles presents vivid reconstructions of historic engagements, shaped by Crane’s aptitude for scene and momentum rather than exhaustive analysis. Last Words, published after his death, gathers stories and sketches that reflect the range of his late work. Taken together, they highlight Crane’s interest in dramatic episodes where character is compressed into decisive motion. Even when recounting distant events, he privileges felt experience over abstract principle, linking these texts to the same sensibility that animates his war tales and urban studies.

The Black Riders and Other Lines and War is Kind distill Crane’s art into compact, often paradoxical poems. The verse favors stark images, plain diction, and an aphoristic turn that exposes self-deception and sentimental habit. The tonal range is wider than the brevity suggests: irony and pity, defiance and humility, move in quick succession. Read alongside the fiction, the poems articulate Crane’s central preoccupations with unusual clarity—human bravado against vast forces, the distance between image and reality, the search for meaning under duress. Together, these books complete a portrait of an author whose concision sharpened, rather than narrowed, his vision.

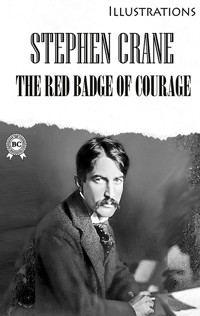

Author Biography

Stephen Crane (1871–1900) was an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist, whose brief career reshaped U.S. prose at the fin de siècle. Best known for The Red Badge of Courage, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, and stories such as The Open Boat, he merged literary realism and naturalism with an impressionistic intensity. His work probed urban poverty, the psychology of fear, and the indifference of nature, challenging romantic views of heroism and war. Though he died young, his stylistic daring—concise, vivid, unsentimental—made him a touchstone for later generations, and many of his texts remain central to American literature courses.

Crane grew up in New Jersey and New York State and began writing early, turning to newspaper sketching and reporting before age twenty. He attended Lafayette College and later Syracuse University for short periods but left without a degree, preferring the newsroom and the streets as classrooms. Immersed in late nineteenth‑century journalism and the American realist tradition, he absorbed techniques of economy, observation, and irony. Encounters with the Bowery and tenement districts of New York furnished material and a critical stance toward social pretense. The press world also connected him to editors who would later syndicate his fiction and dispatches.

His first major work, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, initially appeared in 1893 at his own expense under a pseudonym and was republished in a revised edition a few years later. Its stark portrait of slum life, stripped of moralizing, shocked many readers and attracted a small circle of admirers for its audacity. Crane followed with George’s Mother, continuing his exploration of urban hardship. Although sales were modest, these books established his commitment to unsparing realism and a compressed, scene‑driven style. The critical attention they drew paved the way for wider recognition and positioned him among emerging naturalist writers.

Crane achieved international fame with The Red Badge of Courage, published in the mid‑1890s. Without having seen battle firsthand, he rendered a young soldier’s terror and confusion in a groundbreaking psychological narrative that eschewed patriotic rhetoric for sensory immediacy. The novel’s episodic structure, color imagery, and inward focus distinguished it from earlier war stories, and reviewers on both sides of the Atlantic praised its originality. The book’s success cemented Crane’s reputation and opened opportunities as a correspondent, while also inviting debates about realism, courage, and the reliability of perception—concerns that continued to animate his short fiction and reportage.

Crane’s journalism took him to conflicts and crises that deepened his art. He survived the 1897 wreck of the steamer Commodore off the Florida coast, an ordeal he recast with haunting restraint in The Open Boat. As a correspondent, he covered the Greco‑Turkish War and later the Spanish‑American War in Cuba, experiences reflected in fiction and in collections such as Wounds in the Rain. During these years he also wrote celebrated stories including The Blue Hotel and The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky, honing a spare, elliptical method that uses gesture, dialogue, and setting to expose violence, delusion, and fragile codes.

In parallel with his fiction, Crane published two slim volumes of poetry: The Black Riders and Other Lines and War Is Kind. Their unrhymed, aphoristic pieces startled contemporaries with stark imagery, paradox, and sardonic tone. Many early reviewers were puzzled, but later readers have seen in them an anticipation of modernist brevity and a critique of consoling myth. Across genres, Crane returned to themes of fear, chance, social masquerade, and nature’s indifference, often framing events as parables rather than arguments. His skeptical view of martial glory and sentimental charity is inseparable from his reportage, which sought unvarnished observation.

In his final years, Crane lived partly in England, participating in a literary circle that included figures such as Joseph Conrad and H. G. Wells, while continuing to publish novels, stories, and war correspondence. Chronic illness and financial strain shadowed his productivity, and he died of tuberculosis in Europe in 1900, not yet thirty. His reputation dipped and then revived in the twentieth century, as critics and writers recognized his influence on psychological realism, journalistic prose, and the American short story. Today The Red Badge of Courage and his best tales remain widely studied, admired for their precision, ambiguity, and nerve.

Historical Context

Stephen Crane’s career unfolded between his birth on November 1, 1871, in Newark, New Jersey, and his death on June 5, 1900, in Badenweiler, Germany—years that coincided with America’s turbulent transition from Reconstruction to the Gilded Age and early Progressivism. Raised partly in Port Jervis, New York, he came of age amid industrial expansion, mass immigration, and urban poverty before relocating to New York City’s Bowery in the early 1890s. Journalism launched his literary life and carried him to Florida, Cuba, Greece, and finally England. Across novels, short stories, and poems, he examined war, the city, small-town life, the sea, and the West with unprecedented psychological intensity and stylistic daring.

The explosive growth of New York City in the 1880s and 1890s—tenements crowding the Lower East Side, sweatshops, and Bowery flophouses—formed the social matrix for Crane’s urban fiction and reportage. Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890) and tenement reform campaigns documented conditions that Crane experienced firsthand. The moral economies of settlement houses and temperance activism, championed by figures like his mother, Mary Helen Peck Crane, pushed against entrenched poverty, saloon culture, and vice districts. These realities supplied the human pressures, dialects, and social codes that pervade his depictions of working-class families, precarious livelihoods, and the city’s alternating indifference and menace.

The Panic of 1893 and the deep depression that followed sharpened the stakes for urban survival and shaped Crane’s themes of economic determinism and social fate. Nationwide unemployment, breadlines, and industrial unrest—visible in the Homestead Strike (1892) and the Pullman Strike (1894)—created the gritty backdrop for stories of jobless clerks, day laborers, and barroom drifters. Tammany Hall’s patronage and the Tenderloin’s commercialized vice complicated the era’s moral rhetoric. In this climate, familial authority, religious injunctions, and civic uplift collided with hunger and temptation. Crane’s work records that collision, emphasizing how environment, chance, and social labeling confine—and sometimes destroy—marginal lives.

Crane emerged at the junction of American Realism and European Naturalism, absorbing strains from William Dean Howells and Émile Zola while forging a compressed, impressionistic style. His prose often renders consciousness under stress—battlefields, storm-lashed boats, riotous streets—through sensory fragments and shifting focalization. This experimental method, allied to a skepticism about moral platitudes, shaped both his war narratives and his urban tales. By the late 1890s, with contemporaries like Frank Norris (McTeague, 1899) and Theodore Dreiser (Sister Carrie, 1900), Crane advanced a literature that probed the forces—biological impulse, social conditioning, mass spectacle—governing modern life, while resisting the consolations of sentimental fiction.

Civil War memory saturated late nineteenth-century culture—Grand Army of the Republic reunions, regimental histories, and Century Magazine’s Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (1884–1888) fed popular fascination. Crane, who had not seen combat, drew on such sources and veterans’ testimony to craft psychologically rigorous depictions of fear, courage, and rumor on the battlefield. As the war receded into mythology, his works helped demythologize it, displacing patriotic bombast with interiority and contingency. With over 620,000 dead and an unresolved legacy of emancipation, the conflict’s cultural aftershocks—hero worship, nostalgia, and bitter regional memories—inflect his cycles of Civil War episodes and their stark moral ambiguities.

Crane’s rise owed much to the new mass periodicals and syndicates that accelerated literary fame. Irvin Bacheller’s news and fiction syndicate circulated his writing nationally; D. Appleton & Co. issued The Red Badge of Courage in 1895 after newspaper serialization in 1894. British editors such as W. E. Henley championed Crane, cementing his reputation in London before some American quarters caught up. He contributed to leading magazines—Scribner’s, McClure’s, Collier’s, Harper’s—whose half-tone illustrations, telegraphed news, and broad readership favored vivid, portable scenes. This magazine economy shaped his short stories’ compression, their dramatic framing, and their responsiveness to current events.

Journalism pulled Crane to the sea-lanes and war zones that fueled several collections. In late 1896 he sailed from Jacksonville on the filibustering steamer Commodore to cover Cuba’s insurgency; the ship sank off Florida in early January 1897. That shipwreck—survival in a small dinghy, one man’s death in the surf—became a touchstone for his sea tales, anchored by The Open Boat (1897–1898). His later war sketches synthesized frontline observations into fiction, while posthumous volumes gathered leftover reportage and narratives. Together, these works register the porous borders between assignment and art, draft and story, as late nineteenth-century journalism fed modern short fiction.

The Spanish–American War of 1898 grew out of Cuba’s ongoing War of Independence (1895–1898) and the U.S. battleship Maine’s explosion in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898. After the April declaration of war, American forces fought at Las Guásimas, El Caney, and San Juan and Kettle Hills (July 1) before the siege and surrender of Santiago de Cuba. Correspondents embedded with troops recorded disease, logistics failures, and the frictions of command as much as heroism. Crane’s war prose and poems fold that spectacle into irony, undercutting triumphalism even as he traces the sensations—noise, heat, thirst—by which modern battle imprints itself on memory.

Crane’s European reporting during the Greco–Turkish War (April–May 1897) placed him within a cosmopolitan press corps moving between Athens, the Piraeus, and fronts in Thessaly near Pharsala and Domokos. The conflict, a brief and lopsided Ottoman victory mediated by the Great Powers, exposed how telegraphy, censorship regimes, and competing national narratives shaped war news for readers in London and New York. Crane’s fiction of foreign correspondents, volunteers, and civilians draws on this milieu, blending romantic expectation with the anticlimax and confusion of modern conflict. His experience abroad broadened his canvas from American streets to Europe’s brittle balance of power.

By 1890 the U.S. Census Bureau declared the frontier closed, yet the West persisted in myth and popular fiction. Railroads knit prairies to cities, depositing migrants, drummers, and gamblers into isolated depots and hotels where blizzards, boredom, and bravado bred conflict. Crane’s Western settings probe how codes of masculinity falter when strangers misread one another’s fear, honor, and speech across ethnic and class lines. These stories belong to a post-frontier imagination: the saloon as social theater, the hotel as pressure cooker, the prairie as indifferent backdrop. They demythologize dime-novel heroism while preserving the West’s stark economy of gesture and consequence.

Small-town America supplied Crane a counterpoint to both metropolis and frontier. Port Jervis, an Erie Railroad junction on the Delaware River, informs his fictional Whilomville, where boys’ pranks, local gossip, and civic rituals test community cohesion. These tales unfold as the village meets modernity—rail schedules, telephones, electricity—under the watch of parsons, shopkeepers, and volunteer fire brigades. Child-centered narratives, including gentle pieces about misadventure and discipline, trace the socialization of impulse into manners. This milieu also frames darker studies of conformity, ostracism, and rumor, suggesting that cruelty and courage are cultivated at the parlor and schoolyard long before they reach the battlefield.

The 1890s were marked by the entrenchment of Jim Crow after Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), a national lynching crisis documented by Ida B. Wells, and eruptions like the 1898 Wilmington coup in North Carolina. Crane’s small-town fictions engage the racial terror and moral panic of this era through stories of injury, rescue, and civic retaliation, exposing how reputation, fear, and mob psychology override law. The dilemmas faced by white benefactors and Black laborers in Northern communities mirror larger American contradictions: a nation celebrating emancipation and Union victory while institutionalizing segregation. His portraits anticipate Progressive-era debates over justice, citizenship, and memory.

Crane’s New York years intersected with campaigns against police corruption and commercialized vice. The Lexow Committee (1894–1895) exposed systematic bribery in the Tenderloin; Theodore Roosevelt served as Police Commissioner from 1895 to 1897. In September 1896 Crane publicly testified on behalf of an arrested woman in the Tenderloin, provoking police retaliation and fueling his departure for Florida and war reporting. This entanglement sharpened his preoccupation with authority, reputation, and the unsparing gaze of newspapers. The city’s rough moral marketplace—between reformers, fixers, and the press—permeates his portraits of barrooms, boardinghouses, and street corners where minor incidents spiral into public trials of character.

From 1897 Crane increasingly lived in England, and by 1899 he and Cora Taylor Crane had settled at Brede Place near Rye, Sussex. There he forged friendships with Joseph Conrad, Henry James, and H. G. Wells, and acquainted himself with Ford Madox Hueffer. This Anglo-American circle sharpened his technical experimentation—ellipses, shifting centers of consciousness—and encouraged nautical and colonial subjects. The era’s appetite for historical romance, stoked by Robert Louis Stevenson and Anthony Hope, resonated in his posthumously finished adventure novel The O’Ruddy (completed by Robert Barr, 1903). Society comedies and artist tales likewise reflect transatlantic debates about class, taste, and literary form.

Crane’s poetry belongs to the fin-de-siècle revolt against ornamental verse. The Black Riders and Other Lines (1895) and War Is Kind (1899) deploy aphoristic free verse, biblical cadences, and stark antitheses to interrogate piety, patriotism, and fate. The period’s aesthetic crosscurrents—Symbolism, Decadence, and Art Nouveau design—shaped their presentation, even as the poems’ stripped diction anticipates modernist minimalism. In an age saturated by patriotic oratory and revivalist rhetoric, Crane’s ironies replace uplift with paradox, staging encounters between human longing and an impersonal cosmos. The poems mirror the prose: a science-of-impressions method that treats belief systems as psychological environments under stress.

Chronic illness, debt, and war-wear accelerated Crane’s decline. Tuberculosis symptoms deepened during 1899; friends and patrons in England helped finance treatment on the Continent, where he died at twenty-eight in Badenweiler. Cora Crane and literary allies oversaw the publication of remaining manuscripts and journalism, yielding volumes that extended his reach into the new century. Collections assembled after his death—compendia of war sketches, tales, and essays—reflect editorial choices that crystallized his image as a writer of battle, sea, and city. They also insured that experiments in genre, tone, and perspective would be read alongside the better-known novels.

Crane’s oeuvre foreshadows literary modernism in its skepticism, fragmentation, and attention to sensory data under duress. Later writers—Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, and Ford Madox Ford—acknowledged debts to his clipped diction, irony, and deglamorized combat scenes. His work registers America’s passage from civil strife to empire, from village ethos to metropolitan mass culture, and from moral certainty to psychological complexity. Whether in war narratives, urban sketches, Western parables, domestic vignettes, or compressed lyrics, Crane probes how individuals narrate themselves against impersonal forces—crowd, storm, market, rumor. That historical pressure gives the “complete works” a coherence beyond genre or setting.

Synopsis (Selection)

The Red Badge of Courage

A young Union recruit confronts fear, shame, and the desire for heroism during the Civil War, as the chaos of battle tests his self-image. The narrative emphasizes inner turmoil over military strategy.

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets

In New York’s slums, a young woman seeks escape through romance amid poverty, violence, and social hypocrisy. The novella presents a stark portrait of determinism and urban hardship.

George's Mother

A wayward young man in New York drifts into drinking and swagger under the watchful eye of his pious, domineering mother. The story examines generational conflict, respectability, and urban temptation.

The Third Violet

A light romantic novel set among artists and fashionable society, following a bohemian suitor and a socialite. Their courtship navigates class expectations, vanity, and self-invention.

Active Service

A war-and-romance narrative set amid an overseas conflict, as American civilians and correspondents are drawn to the front. It contrasts imagined glory with the realities of modern warfare and public spectacle.

The Monster

In a small town, an African American coachman is disfigured after a heroic rescue and becomes a target of communal ostracism. The novella probes race, gratitude, and moral courage.

The O'Ruddy

A swashbuckling historical romance about an Irish adventurer seeking a contested inheritance and love in 18th-century Britain. The tale blends duels, intrigue, and humor.

The Little Regiment and Other Episodes from the American Civil War

Civil War vignettes focused on ordinary Union soldiers in camp and combat. The stories stress comradeship, fear, and the immediacy of battle over grand narratives.

The Open Boat and Other Stories

Naturalistic tales led by a shipwreck survival story in which four men in a dinghy test endurance and fate. Companion pieces explore isolation, perception, and chance.

Blue Hotel & His New Mittens

A paired volume contrasting a tense prairie drama of suspicion and fatal misunderstanding with a gentle small-town tale of childhood pride and embarrassment.

Whilomville Stories

Interlinked sketches of a small American town, often through children’s eyes. Themes include mischief, cruelty, loyalty, and the unwritten rules of community life.

Wounds in the Rain: War Stories

Reportage-like fiction from the Spanish–American War, depicting soldiers, sailors, and correspondents in moments of confusion and bravery. Bureaucratic frictions and the fog of war are recurring concerns.

Great Battles of the World

Dramatic retellings of famous engagements across history. Emphasis falls on atmosphere, human stakes, and shifting fortunes rather than technical analysis.

Last Words

A posthumous miscellany of stories, sketches, and journalism ranging from urban scenes to battlefront episodes. The pieces share terse observation, irony, and an eye for chance.

Other Short Stories

Additional tales spanning urban realism, frontier episodes, and psychological studies. Recurring themes include fear, courage, social codes, and accident.

The Black Riders and Other Lines

Compact, epigrammatic poems in a biblical cadence that question faith, authority, and the self. Stark imagery and paradox drive their skeptical force.

War is Kind

An ironically titled collection juxtaposing martial rhetoric with scenes of loss and brutality. Short lyrics about war and love underscore the pity and absurdity of battle.

The Complete Works of Stephen Crane

Novels and Novellas

The Red Badge of Courage

CHAPTER I.

The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army stretched out on the hills, resting. As the landscape changed from brown to green, the army awakened, and began to tremble with eagerness at the noise of rumors. It cast its eyes upon the roads, which were growing from long troughs of liquid mud to proper thoroughfares. A river, amber-tinted in the shadow of its banks, purled at the army's feet; and at night, when the stream had become of a sorrowful blackness, one could see across it the red, eyelike gleam of hostile camp-fires set in the low brows of distant hills.

Once a certain tall soldier developed virtues and went resolutely to wash a shirt. He came flying back from a brook waving his garment bannerlike. He was swelled with a tale he had heard from a reliable friend, who had heard it from a truthful cavalryman, who had heard it from his trustworthy brother, one of the orderlies at division headquarters. He adopted the important air of a herald in red and gold. "We're goin' t' move t'morrah—sure," he said pompously to a group in the company street. "We're goin' 'way up the river, cut across, an' come around in behint 'em."

To his attentive audience he drew a loud and elaborate plan of a very brilliant campaign. When he had finished, the blue-clothed men scattered into small arguing groups between the rows of squat brown huts. A negro teamster who had been dancing upon a cracker box with the hilarious encouragement of twoscore soldiers was deserted. He sat mournfully down. Smoke drifted lazily from a multitude of quaint chimneys.

"It's a lie! that's all it is—a thunderin' lie!" said another private loudly. His smooth face was flushed, and his hands were thrust sulkily into his trousers' pockets. He took the matter as an affront to him. "I don't believe the derned old army's ever going to move. We're set. I've got ready to move eight times in the last two weeks, and we ain't moved yet."

The tall soldier felt called upon to defend the truth of a rumor he himself had introduced. He and the loud one came near to fighting over it.

A corporal began to swear before the assemblage. He had just put a costly board floor in his house, he said. During the early spring he had refrained from adding extensively to the comfort of his environment because he had felt that the army might start on the march at any moment. Of late, however, he had been impressed that they were in a sort of eternal camp.

Many of the men engaged in a spirited debate. One outlined in a peculiarly lucid manner all the plans of the commanding general. He was opposed by men who advocated that there were other plans of campaign. They clamored at each other, numbers making futile bids for the popular attention. Meanwhile, the soldier who had fetched the rumor bustled about with much importance. He was continually assailed by questions.

"What's up, Jim?"

"Th' army's goin' t' move."

"Ah, what yeh talkin' about? How yeh know it is?"

"Well, yeh kin b'lieve me er not, jest as yeh like. I don't care a hang."

There was much food for thought in the manner in which he replied. He came near to convincing them by disdaining to produce proofs. They grew excited over it.

There was a youthful private who listened with eager ears to the words of the tall soldier and to the varied comments of his comrades. After receiving a fill of discussions concerning marches and attacks, he went to his hut and crawled through an intricate hole that served it as a door. He wished to be alone with some new thoughts that had lately come to him.

He lay down on a wide bank that stretched across the end of the room. In the other end, cracker boxes were made to serve as furniture. They were grouped about the fireplace. A picture from an illustrated weekly was upon the log walls, and three rifles were paralleled on pegs. Equipments hunt on handy projections, and some tin dishes lay upon a small pile of firewood. A folded tent was serving as a roof. The sunlight, without, beating upon it, made it glow a light yellow shade. A small window shot an oblique square of whiter light upon the cluttered floor. The smoke from the fire at times neglected the clay chimney and wreathed into the room, and this flimsy chimney of clay and sticks made endless threats to set ablaze the whole establishment.

The youth was in a little trance of astonishment. So they were at last going to fight. On the morrow, perhaps, there would be a battle, and he would be in it. For a time he was obliged to labor to make himself believe. He could not accept with assurance an omen that he was about to mingle in one of those great affairs of the earth.

He had, of course, dreamed of battles all his life—of vague and bloody conflicts that had thrilled him with their sweep and fire. In visions he had seen himself in many struggles. He had imagined peoples secure in the shadow of his eagle-eyed prowess. But awake he had regarded battles as crimson blotches on the pages of the past. He had put them as things of the bygone with his thought-images of heavy crowns and high castles. There was a portion of the world's history which he had regarded as the time of wars, but it, he thought, had been long gone over the horizon and had disappeared forever.

From his home his youthful eyes had looked upon the war in his own country with distrust. It must be some sort of a play affair. He had long despaired of witnessing a Greeklike struggle. Such would be no more, he had said. Men were better, or more timid. Secular and religious education had effaced the throat-grappling instinct, or else firm finance held in check the passions.

He had burned several times to enlist. Tales of great movements shook the land. They might not be distinctly Homeric, but there seemed to be much glory in them. He had read of marches, sieges, conflicts, and he had longed to see it all. His busy mind had drawn for him large pictures extravagant in color, lurid with breathless deeds.

But his mother had discouraged him. She had affected to look with some contempt upon the quality of his war ardor and patriotism. She could calmly seat herself and with no apparent difficulty give him many hundreds of reasons why he was of vastly more importance on the farm than on the field of battle. She had had certain ways of expression that told him that her statements on the subject came from a deep conviction. Moreover, on her side, was his belief that her ethical motive in the argument was impregnable.

At last, however, he had made firm rebellion against this yellow light thrown upon the color of his ambitions. The newspapers, the gossip of the village, his own picturings had aroused him to an uncheckable degree. They were in truth fighting finely down there. Almost every day the newspapers printed accounts of a decisive victory.

One night, as he lay in bed, the winds had carried to him the clangoring of the church bell as some enthusiast jerked the rope frantically to tell the twisted news of a great battle. This voice of the people rejoicing in the night had made him shiver in a prolonged ecstasy of excitement. Later, he had gone down to his mother's room and had spoken thus: "Ma, I'm going to enlist."

"Henry, don't you be a fool," his mother had replied. She had then covered her face with the quilt. There was an end to the matter for that night.

Nevertheless, the next morning he had gone to a town that was near his mother's farm and had enlisted in a company that was forming there. When he had returned home his mother was milking the brindle cow. Four others stood waiting. "Ma, I've enlisted," he had said to her diffidently. There was a short silence. "The Lord's will be done, Henry," she had finally replied, and had then continued to milk the brindle cow.

When he had stood in the doorway with his soldier's clothes on his back, and with the light of excitement and expectancy in his eyes almost defeating the glow of regret for the home bonds, he had seen two tears leaving their trails on his mother's scarred cheeks.

Still, she had disappointed him by saying nothing whatever about returning with his shield or on it. He had privately primed himself for a beautiful scene. He had prepared certain sentences which he thought could be used with touching effect. But her words destroyed his plans. She had doggedly peeled potatoes and addressed him as follows: "You watch out, Henry, an' take good care of yerself in this here fighting business—you watch out, an' take good care of yerself. Don't go a-thinkin' you can lick the hull rebel army at the start, because yeh can't. Yer jest one little feller amongst a hull lot of others, and yeh've got to keep quiet an' do what they tell yeh. I know how you are, Henry.

"I've knet yeh eight pair of socks, Henry, and I've put in all yer best shirts, because I want my boy to be jest as warm and comf'able as anybody in the army. Whenever they get holes in 'em, I want yeh to send 'em right-away back to me, so's I kin dern 'em.

"An' allus be careful an' choose yer comp'ny. There's lots of bad men in the army, Henry. The army makes 'em wild, and they like nothing better than the job of leading off a young feller like you, as ain't never been away from home much and has allus had a mother, an' a-learning 'em to drink and swear. Keep clear of them folks, Henry. I don't want yeh to ever do anything, Henry, that yeh would be 'shamed to let me know about. Jest think as if I was a-watchin' yeh. If yeh keep that in yer mind allus, I guess yeh'll come out about right.

"Yeh must allus remember yer father, too, child, an' remember he never drunk a drop of licker in his life, and seldom swore a cross oath.

"I don't know what else to tell yeh, Henry, excepting that yeh must never do no shirking, child, on my account. If so be a time comes when yeh have to be kilt or do a mean thing, why, Henry, don't think of anything 'cept what's right, because there's many a woman has to bear up 'ginst sech things these times, and the Lord 'll take keer of us all.

"Don't forgit about the socks and the shirts, child; and I've put a cup of blackberry jam with yer bundle, because I know yeh like it above all things. Good-by, Henry. Watch out, and be a good boy."

He had, of course, been impatient under the ordeal of this speech. It had not been quite what he expected, and he had borne it with an air of irritation. He departed feeling vague relief.

Still, when he had looked back from the gate, he had seen his mother kneeling among the potato parings. Her brown face, upraised, was stained with tears, and her spare form was quivering. He bowed his head and went on, feeling suddenly ashamed of his purposes.

From his home he had gone to the seminary to bid adieu to many schoolmates. They had thronged about him with wonder and admiration. He had felt the gulf now between them and had swelled with calm pride. He and some of his fellows who had donned blue were quite overwhelmed with privileges for all of one afternoon, and it had been a very delicious thing. They had strutted.

A certain light-haired girl had made vivacious fun at his martial spirit, but there was another and darker girl whom he had gazed at steadfastly, and he thought she grew demure and sad at sight of his blue and brass. As he had walked down the path between the rows of oaks, he had turned his head and detected her at a window watching his departure. As he perceived her, she had immediately begun to stare up through the high tree branches at the sky. He had seen a good deal of flurry and haste in her movement as she changed her attitude. He often thought of it.

On the way to Washington his spirit had soared. The regiment was fed and caressed at station after station until the youth had believed that he must be a hero. There was a lavish expenditure of bread and cold meats, coffee, and pickles and cheese. As he basked in the smiles of the girls and was patted and complimented by the old men, he had felt growing within him the strength to do mighty deeds of arms.

After complicated journeyings with many pauses, there had come months of monotonous life in a camp. He had had the belief that real war was a series of death struggles with small time in between for sleep and meals; but since his regiment had come to the field the army had done little but sit still and try to keep warm.

He was brought then gradually back to his old ideas. Greeklike struggles would be no more. Men were better, or more timid. Secular and religious education had effaced the throat-grappling instinct, or else firm finance held in check the passions.

He had grown to regard himself merely as a part of a vast blue demonstration. His province was to look out, as far as he could, for his personal comfort. For recreation he could twiddle his thumbs and speculate on the thoughts which must agitate the minds of the generals. Also, he was drilled and drilled and reviewed, and drilled and drilled and reviewed.

The only foes he had seen were some pickets along the river bank. They were a sun-tanned, philosophical lot, who sometimes shot reflectively at the blue pickets. When reproached for this afterward, they usually expressed sorrow, and swore by their gods that the guns had exploded without their permission. The youth, on guard duty one night, conversed across the stream with one of them. He was a slightly ragged man, who spat skillfully between his shoes and possessed a great fund of bland and infantile assurance. The youth liked him personally.

"Yank," the other had informed him, "yer a right dum good feller." This sentiment, floating to him upon the still air, had made him temporarily regret war.

Various veterans had told him tales. Some talked of gray, bewhiskered hordes who were advancing with relentless curses and chewing tobacco with unspeakable valor; tremendous bodies of fierce soldiery who were sweeping along like the Huns. Others spoke of tattered and eternally hungry men who fired despondent powders. "They'll charge through hell's fire an' brimstone t' git a holt on a haversack, an' sech stomachs ain't a-lastin' long," he was told. From the stories, the youth imagined the red, live bones sticking out through slits in the faded uniforms.

Still, he could not put a whole faith in veterans' tales, for recruits were their prey. They talked much of smoke, fire, and blood, but he could not tell how much might be lies. They persistently yelled "Fresh fish!" at him, and were in no wise to be trusted.

However, he perceived now that it did not greatly matter what kind of soldiers he was going to fight, so long as they fought, which fact no one disputed. There was a more serious problem. He lay in his bunk pondering upon it. He tried to mathematically prove to himself that he would not run from a battle.

Previously he had never felt obliged to wrestle too seriously with this question. In his life he had taken certain things for granted, never challenging his belief in ultimate success, and bothering little about means and roads. But here he was confronted with a thing of moment. It had suddenly appeared to him that perhaps in a battle he might run. He was forced to admit that as far as war was concerned he knew nothing of himself.

A sufficient time before he would have allowed the problem to kick its heels at the outer portals of his mind, but now he felt compelled to give serious attention to it.

A little panic-fear grew in his mind. As his imagination went forward to a fight, he saw hideous possibilities. He contemplated the lurking menaces of the future, and failed in an effort to see himself standing stoutly in the midst of them. He recalled his visions of broken-bladed glory, but in the shadow of the impending tumult he suspected them to be impossible pictures.

He sprang from the bunk and began to pace nervously to and fro. "Good Lord, what's th' matter with me?" he said aloud.

He felt that in this crisis his laws of life were useless. Whatever he had learned of himself was here of no avail. He was an unknown quantity. He saw that he would again be obliged to experiment as he had in early youth. He must accumulate information of himself, and meanwhile he resolved to remain close upon his guard lest those qualities of which he knew nothing should everlastingly disgrace him. "Good Lord!" he repeated in dismay.

After a time the tall soldier slid dexterously through the hole. The loud private followed. They were wrangling.

"That's all right," said the tall soldier as he entered. He waved his hand expressively. "You can believe me or not, jest as you like. All you got to do is to sit down and wait as quiet as you can. Then pretty soon you'll find out I was right."

His comrade grunted stubbornly. For a moment he seemed to be searching for a formidable reply. Finally he said: "Well, you don't know everything in the world, do you?"

"Didn't say I knew everything in the world," retorted the other sharply. He began to stow various articles snugly into his knapsack.

The youth, pausing in his nervous walk, looked down at the busy figure. "Going to be a battle, sure, is there, Jim?" he asked.

"Of course there is," replied the tall soldier. "Of course there is. You jest wait 'til to-morrow, and you'll see one of the biggest battles ever was. You jest wait."

"Thunder!" said the youth.

"Oh, you'll see fighting this time, my boy, what'll be regular out-and-out fighting," added the tall soldier, with the air of a man who is about to exhibit a battle for the benefit of his friends.

"Huh!" said the loud one from a corner.

"Well," remarked the youth, "like as not this story'll turn out jest like them others did."

"Not much it won't," replied the tall soldier, exasperated. "Not much it won't. Didn't the cavalry all start this morning?" He glared about him. No one denied his statement. "The cavalry started this morning," he continued. "They say there ain't hardly any cavalry left in camp. They're going to Richmond, or some place, while we fight all the Johnnies. It's some dodge like that. The regiment's got orders, too. A feller what seen 'em go to headquarters told me a little while ago. And they're raising blazes all over camp—anybody can see that."

"Shucks!" said the loud one.

The youth remained silent for a time. At last he spoke to the tall soldier. "Jim!"

"What?"

"How do you think the reg'ment 'll do?"

"Oh, they'll fight all right, I guess, after they once get into it," said the other with cold judgment. He made a fine use of the third person. "There's been heaps of fun poked at 'em because they're new, of course, and all that; but they'll fight all right, I guess."

"Think any of the boys 'll run?" persisted the youth.

"Oh, there may be a few of 'em run, but there's them kind in every regiment, 'specially when they first goes under fire," said the other in a tolerant way. "Of course it might happen that the hull kit-and-boodle might start and run, if some big fighting came first-off, and then again they might stay and fight like fun. But you can't bet on nothing. Of course they ain't never been under fire yet, and it ain't likely they'll lick the hull rebel army all-to-oncet the first time; but I think they'll fight better than some, if worse than others. That's the way I figger. They call the reg'ment 'Fresh fish' and everything; but the boys come of good stock, and most of 'em 'll fight like sin after they oncet git shootin'," he added, with a mighty emphasis on the last four words.

"Oh, you think you know—" began the loud soldier with scorn.

The other turned savagely upon him. They had a rapid altercation, in which they fastened upon each other various strange epithets.

The youth at last interrupted them. "Did you ever think you might run yourself, Jim?" he asked. On concluding the sentence he laughed as if he had meant to aim a joke. The loud soldier also giggled.

The tall private waved his hand. "Well," said he profoundly, "I've thought it might get too hot for Jim Conklin in some of them scrimmages, and if a whole lot of boys started and run, why, I s'pose I'd start and run. And if I once started to run, I'd run like the devil, and no mistake. But if everybody was a-standing and a-fighting, why, I'd stand and fight. Be jiminey, I would. I'll bet on it."

"Huh!" said the loud one.

The youth of this tale felt gratitude for these words of his comrade. He had feared that all of the untried men possessed a great and correct confidence. He now was in a measure reassured.

CHAPTER II.

The next morning the youth discovered that his tall comrade had been the fast-flying messenger of a mistake. There was much scoffing at the latter by those who had yesterday been firm adherents of his views, and there was even a little sneering by men who had never believed the rumor. The tall one fought with a man from Chatfield Corners and beat him severely.

The youth felt, however, that his problem was in no wise lifted from him. There was, on the contrary, an irritating prolongation. The tale had created in him a great concern for himself. Now, with the newborn question in his mind, he was compelled to sink back into his old place as part of a blue demonstration.

For days he made ceaseless calculations, but they were all wondrously unsatisfactory. He found that he could establish nothing. He finally concluded that the only way to prove himself was to go into the blaze, and then figuratively to watch his legs to discover their merits and faults. He reluctantly admitted that he could not sit still and with a mental slate and pencil derive an answer. To gain it, he must have blaze, blood, and danger, even as a chemist requires this, that, and the other. So he fretted for an opportunity.

Meanwhile he continually tried to measure himself by his comrades. The tall soldier, for one, gave him some assurance. This man's serene unconcern dealt him a measure of confidence, for he had known him since childhood, and from his intimate knowledge he did not see how he could be capable of anything that was beyond him, the youth. Still, he thought that his comrade might be mistaken about himself. Or, on the other hand, he might be a man heretofore doomed to peace and obscurity, but, in reality, made to shine in war.

The youth would have liked to have discovered another who suspected himself. A sympathetic comparison of mental notes would have been a joy to him.

He occasionally tried to fathom a comrade with seductive sentences. He looked about to find men in the proper mood. All attempts failed to bring forth any statement which looked in any way like a confession to those doubts which he privately acknowledged in himself. He was afraid to make an open declaration of his concern, because he dreaded to place some unscrupulous confidant upon the high plane of the unconfessed from which elevation he could be derided.

In regard to his companions his mind wavered between two opinions, according to his mood. Sometimes he inclined to believing them all heroes. In fact, he usually admitted in secret the superior development of the higher qualities in others. He could conceive of men going very insignificantly about the world bearing a load of courage unseen, and although he had known many of his comrades through boyhood, he began to fear that his judgment of them had been blind. Then, in other moments, he flouted these theories, and assured himself that his fellows were all privately wondering and quaking.

His emotions made him feel strange in the presence of men who talked excitedly of a prospective battle as of a drama they were about to witness, with nothing but eagerness and curiosity apparent in their faces. It was often that he suspected them to be liars.

He did not pass such thoughts without severe condemnation of himself. He dinned reproaches at times. He was convicted by himself of many shameful crimes against the gods of traditions.

In his great anxiety his heart was continually clamoring at what he considered the intolerable slowness of the generals. They seemed content to perch tranquilly on the river bank, and leave him bowed down by the weight of a great problem. He wanted it settled forthwith. He could not long bear such a load, he said. Sometimes his anger at the commanders reached an acute stage, and he grumbled about the camp like a veteran.

One morning, however, he found himself in the ranks of his prepared regiment. The men were whispering speculations and recounting the old rumors. In the gloom before the break of the day their uniforms glowed a deep purple hue. From across the river the red eyes were still peering. In the eastern sky there was a yellow patch like a rug laid for the feet of the coming sun; and against it, black and patternlike, loomed the gigantic figure of the colonel on a gigantic horse.

From off in the darkness came the trampling of feet. The youth could occasionally see dark shadows that moved like monsters. The regiment stood at rest for what seemed a long time. The youth grew impatient. It was unendurable the way these affairs were managed. He wondered how long they were to be kept waiting.

As he looked all about him and pondered upon the mystic gloom, he began to believe that at any moment the ominous distance might be aflare, and the rolling crashes of an engagement come to his ears. Staring once at the red eyes across the river, he conceived them to be growing larger, as the orbs of a row of dragons advancing. He turned toward the colonel and saw him lift his gigantic arm and calmly stroke his mustache.

At last he heard from along the road at the foot of the hill the clatter of a horse's galloping hoofs. It must be the coming of orders. He bent forward, scarce breathing. The exciting clickety-click, as it grew louder and louder, seemed to be beating upon his soul. Presently a horseman with jangling equipment drew rein before the colonel of the regiment. The two held a short, sharp-worded conversation. The men in the foremost ranks craned their necks.

As the horseman wheeled his animal and galloped away he turned to shout over his shoulder, "Don't forget that box of cigars!" The colonel mumbled in reply. The youth wondered what a box of cigars had to do with war.

A moment later the regiment went swinging off into the darkness. It was now like one of those moving monsters wending with many feet. The air was heavy, and cold with dew. A mass of wet grass, marched upon, rustled like silk.

There was an occasional flash and glimmer of steel from the backs of all these huge crawling reptiles. From the road came creakings and grumblings as some surly guns were dragged away.

The men stumbled along still muttering speculations. There was a subdued debate. Once a man fell down, and as he reached for his rifle a comrade, unseeing, trod upon his hand. He of the injured fingers swore bitterly and aloud. A low, tittering laugh went among his fellows.

Presently they passed into a roadway and marched forward with easy strides. A dark regiment moved before them, and from behind also came the tinkle of equipments on the bodies of marching men.

The rushing yellow of the developing day went on behind their backs. When the sunrays at last struck full and mellowingly upon the earth, the youth saw that the landscape was streaked with two long, thin, black columns which disappeared on the brow of a hill in front and rearward vanished in a wood. They were like two serpents crawling from the cavern of the night.

The river was not in view. The tall soldier burst into praises of what he thought to be his powers of perception.

Some of the tall one's companions cried with emphasis that they, too, had evolved the same thing, and they congratulated themselves upon it. But there were others who said that the tall one's plan was not the true one at all. They persisted with other theories. There was a vigorous discussion.

The youth took no part in them. As he walked along in careless line he was engaged with his own eternal debate. He could not hinder himself from dwelling upon it. He was despondent and sullen, and threw shifting glances about him. He looked ahead, often expecting to hear from the advance the rattle of firing.

But the long serpents crawled slowly from hill to hill without bluster of smoke. A dun-colored cloud of dust floated away to the right. The sky overhead was of a fairy blue.

The youth studied the faces of his companions, ever on the watch to detect kindred emotions. He suffered disappointment. Some ardor of the air which was causing the veteran commands to move with glee—almost with song—had infected the new regiment. The men began to speak of victory as of a thing they knew. Also, the tall soldier received his vindication. They were certainly going to come around in behind the enemy. They expressed commiseration for that part of the army which had been left upon the river bank, felicitating themselves upon being a part of a blasting host.

The youth, considering himself as separated from the others, was saddened by the blithe and merry speeches that went from rank to rank. The company wags all made their best endeavors. The regiment tramped to the tune of laughter.

The blatant soldier often convulsed whole files by his biting sarcasms aimed at the tall one.

And it was not long before all the men seemed to forget their mission. Whole brigades grinned in unison, and regiments laughed.

A rather fat soldier attempted to pilfer a horse from a dooryard. He planned to load his knap-sack upon it. He was escaping with his prize when a young girl rushed from the house and grabbed the animal's mane. There followed a wrangle. The young girl, with pink cheeks and shining eyes, stood like a dauntless statue.

The observant regiment, standing at rest in the roadway, whooped at once, and entered whole-souled upon the side of the maiden. The men became so engrossed in this affair that they entirely ceased to remember their own large war. They jeered the piratical private, and called attention to various defects in his personal appearance; and they were wildly enthusiastic in support of the young girl.

To her, from some distance, came bold advice. "Hit him with a stick."

There were crows and catcalls showered upon him when he retreated without the horse. The regiment rejoiced at his downfall. Loud and vociferous congratulations were showered upon the maiden, who stood panting and regarding the troops with defiance.

At nightfall the column broke into regimental pieces, and the fragments went into the fields to camp. Tents sprang up like strange plants. Camp fires, like red, peculiar blossoms, dotted the night.

The youth kept from intercourse with his companions as much as circumstances would allow him. In the evening he wandered a few paces into the gloom. From this little distance the many fires, with the black forms of men passing to and fro before the crimson rays, made weird and satanic effects.

He lay down in the grass. The blades pressed tenderly against his cheek. The moon had been lighted and was hung in a treetop. The liquid stillness of the night enveloping him made him feel vast pity for himself. There was a caress in the soft winds; and the whole mood of the darkness, he thought, was one of sympathy for himself in his distress.