INTRODUCTION

I remember I was homesick in North Africa, twenty-three years old and teaching English in a shabby, sidestreet language school. Young and homesick, and in the evenings drinking red Algerian wine and writing poetry … a poem about a cormorant, when I was longing to be home in England or breathing the salt air of a beach in Wales. I was trying to catch the paradox of the bird, its dual nature … its satanic silhouette as it stood on the rocks and dried its cloak of wings, its silvery sleekness as it dived and hunted underwater.

I remember a few years later, doing my teaching practice in Dorset … bitterly bleak in January, huddling in the evenings in a pub in Lyme Regis. The landlord had broken his wrist and had a steel pin inserted, and from time to time his professional cheeriness was spoilt by a stab of pain and a violent mood. I wrote a story about him … he found an oily cormorant on the beach and brought it into his bar, and somehow its quirky nature, its croaks and squirty mutes made him calm and sane.

And when I had the courage to quit the security of teaching, to rent a caravan in Snowdonia and try to write a book, the cormorant was still with me. The same essential paradox of the bird intrigued me. Its dual nature – its beauty in the water and yet its sinister gluttony – appealed to me as a subject for another, longer story. Through my first winter in the Welsh mountains I wrote and re-wrote the novel, it grew darker and odder in its re-writing, and my agent sold it to the first publisher to read it.

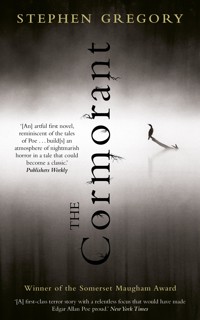

The Cormoranthas proved strangely resilient. Nearly thirty years since I wrote the book, it still provokes responses and interest. In its first publications in the United Kingdom and the United States and in translations, it had flattering reviews and I received some vile, anonymous hate mail. On the same morning I sat in the sunshine beside the river Gwyrfai and opened a letter to say that the book had won the Somerset Maugham Award, I had a scrawly, handwritten note to wish that I would rot in hell for writing such an obscenity. I was excited by both.

Since then, the book has been made into a gem of a television movie, directed by Peter Markham and starring the Oscar-nominated actor Ralph Fiennes. Peter came to talk to me about the project, and even before he’d stepped through the door of my cottage on the Foryd estuary a few miles south of Caernarfon, he told me he was thrilled about the book but of course we would have to change the ending. The book is small and dark and sinewy, with a shocking climax; for the movie we re-wrote a treatment and the script was opened up with more amenable characters and a different, less disturbing resolution. Peter made a lovely, haunting film, but it remains an ambition of mine to see the essential nightmare of the novel put onto the screen.

The Cormorantaroused the interest of the director William Friedkin, infamous forThe Exorcist. He’d found the book in a small-press American edition and liked it so much he flew me to Hollywood to write a screenplay for him at Paramount Studios … he liked my ideas and treatments, but my script spiralled into what he called ‘development hell’ and I came home to my novel-writing in Wales. Years later, parts of the screenplay are just recognisable in a horror B-movie which went straight to video, but I cherish the memory of my time there and the tiny imprint my material has left on the Hollywood film industry.

Birds, and the wild countryside, especially the woods and beaches and mountains of Wales… it’s the material I’ve loved to work with and use as the setting for my stories. One review had said that my writing was a fusion of Stephen King and the English nature-poet Ted Hughes, and the cormorant was the perfect foil for my first book. Since then I’ve tried in different novels, with different degrees of success, to capture the essence of other creatures as a way to open up the flaws and weaknesses of my human characters.

InThe Blood of Angels, an ammonite or a brittlestar or even a natterjack toad might have a special significance. InThe Wood-witch, the protagonist is obsessed with the eerie, luminous growth of a gruesome fungus. InPlague of Gulls, a young man and the seaside town he lives in are bullied by black-backs. InThe Perils and Dangers of this Night, a boy trapped in an old boarding-school finds a little solace with his rescued jackdaw. And in my current work-in-progress,The Waking That Kills, the miraculous, mysterious swifts, known as ‘devil birds’ by country folk, are the stuff of a midsummer nightmare.

The Cormorantis still bringing unexpected letters and offers into my e-mail inbox. It’s about a young man, who, like me, gave up schoolteaching to go and live in the mountains of Snowdonia … who, like me, was confronted by the vagaries of winter in Wales and the unpredictable moods of the weather. Unlike me, my narrator encountered such an unsettling horror that everything he loved most was threatened with destruction. Not in the cormorant, not in the bird itself which preoccupied and obsessed him… but in his own imagination and the dangerous, deadly cracks which opened within it.

It’s a brooding, confronting tale, perhaps too uncomfortable for a squeamish reader, and, thirty years since I conjured it from its earliest manifestations, it still provokes a strong reaction. Like the bird, the book is beautiful and ugly, intriguing and upsetting, appealing and appalling, in its different, changing moods.

Stephen Gregory

March 21, 2013

I

The crate was delivered to the cottage at five o’clock in the afternoon. Two men carried it into our little living-room, put it down in front of the fire, and then they drove away in their van. For the next four hours, I left it there and continued working at my desk. I built up the fire with coal and a few freshly-split logs of spruce from the forest, cooked some supper, leaving some to stay warm for my wife until she came in from working in the village. Outside, it grew dark and there was the pattering of fine rain on the windows of the cottage. The wind blew up and made the trees of the plantation rattle. It was October. I could hear the tumbling of the stream at the foot of the garden, a reassuring sound, a background to the explosive crackle of the logs, the whining of wet wood in the growing heat of the fire. A curtain of drizzle concealed the mountains, they were dissolved into the sky, removed from around the village as though they had never been there. I worked for a while and I ate. The crate stood silent on the rug, in front of the hearth.

It was a box of white wood, about three feet square, with a panel of perforations on the top to ventilate the contents. Once or twice, in the course of the evening, I got up from the desk, knelt by the crate and sniffed at the tiny holes. I blew into them. I smelt the new wood, its clean, useful smell, and from the perforations there came the pungent whiff of the beach, the rotten air of an estuary which dries a little and sweats before the return of the cleansing tide. Inside the box, there was something warm and breathing, asleep perhaps, sleeping in a bed of stale straw. No sound, no movement. I returned to my work, but I was restless so I abandoned it for another look at the newspaper. Sometimes, as I read, my hand strayed and rested on the corner of the white wooden crate. When my wife came in at nine o’clock we would open it together.

Ann went immediately upstairs to take off her wet clothes and to inspect the baby. I could hear her shaking her coat, and imagined the shower of raindrops against the mirror in the bedroom as she dried her thick, brown hair with a towel. She went to the tiny back room and found the baby sound asleep; I had been up to check that he was alright each time I left my desk, my paper and the crate. She came down again, her cheeks pink with her efforts on the bicycle through the enveloping darkness and with the business of drying her hair. She was carrying the cat by the scruff of its neck.

‘Don’t let the cat go upstairs when Harry’s in bed,’ she said, dropping the animal unceremoniously onto the sofa. ‘It was curled up on his pillow. Otherwise, my love,’ and she presented her cheek for me to kiss, ‘everything seems to be in order. Good boy.’

The cat leapt across the room and sniffed at the box. It arched its back, rubbed itself luxuriously on the corners of the crate.

‘So,’ said Ann. ‘It’s arrived. Let’s open it and see what we’ve got.’

The fire was burning quickly in the grate. A gust of wind in the chimney sent out the plumes of sweet, blue smoke into the warm room. There was the intimate glow of a table lamp which focussed its circle of light on my typewriter and picked up the white brightness of my pads of paper. On the walls, the strong primary colours of our prints glowed in the flickering firelight, the spines of the paperback books were a brilliant abstract impression in themselves. The thick rugs seemed to ripple with warmth in the cosy room. The cat rumbled contentedly. Upstairs, the baby was asleep.

I went to the kitchen and came back with a screwdriver. It would be easy to open the crate. The top panel with its rows of holes came away with three gentle probings of the screwdriver. I put the lid and its twisted staples on an armchair. Together, we looked down into the box, grimacing at the smell which sprang powerfully up from inside and eclipsed the sweetness of the fire, the scent of my wife’s hair. There was a thick layer of straw; it moved a little with the sudden intrusion of light. I drew aside the bedding, moving gingerly and snatching away my hand. Ann chuckled and nudged my arm, but she would not reach down into the damp straw. The cat had withdrawn to a vantage point on top of the writing-desk, where it basked like a goddess in the circle of light. Its eyes were fixed on the crate, it sneezed quietly at the rising reek. Something was coming awake, shifting among the straw.

The crate creaked. A log spilled from its bed of coal and fell onto the hearth with a splintering of sparks. From out of its nest of straw, as though summoned by the signal from the fire, the bird put up its head. It yawned, showing a wormlike tongue and issuing a stink of seaweed.

Ann and I recoiled. The cat leapt onto the typewriter with an electric bristling of fur. Shedding its covering of straw, shaking itself free of its bedding, the bird rose out of the pit of its crate. The cormorant emerged in front of the fire. It lifted its wings clear of the box, hooked with its long beak onto the top of its wooden prison. Aroused from its slumbers by the direct heat of the flames, it heaved itself out of the box and collapsed on its breast on the carpet of the living-room. I felt Ann’s hand at my arm, tugging me backwards. Together, we shrank to the foot of the stairs which led up from the room. The cat was quivering with surprise. And the cormorant picked itself up, straightened its ruffled feathers with a few deft movements of its beak, stretching out its tattered, black wings and shaking them, like an elderly clergyman flapping the dust from his gown. It sprang onto the sofa, where it raised its tail and shot out a jet of white-brown shit which struck the wooden crate with a slap before trickling towards the carpet.

Ann squealed and took three steps up.

‘Get it out. For God’s sake, get the thing outside!’

I stepped forward, instinctively reaching for a heavy cushion from an armchair, and advanced on the big, gooselike bird, wafting at its face with my weapon. The bird retreated. Its neck writhed and the horny beak made sporadic thrusts at the cushion. I forced it backwards into the corner by the writing-desk, as the cat fled with a loud hissing and its question-mark of a tail held up. The cormorant went under the table, lodged itself among the legs and peered out, like an eel in its underwater lair. It shot a yellow jet into the skirting board, pattered its webbed feet wetly into the carpet.

‘Get it into the crate. Get it out from under the table.’ Ann’s voice was shrill with panic.

I reached for the box and turned it onto its side in the middle of the room, with the intention of driving the bird back into the prison. Straw fell out and steamed in the heat of the fire. By tapping bluntly on the table with the poker, I forced the cormorant out. By now, it had found its voice, an ugly, rasping yell which drew from the cat a series of spitting coughs. The bird leapt clumsily from its den, beat its wings just twice as it somersaulted through the air, knocking the lamp from its table and sending up a whirlwind of paper from around the typewriter. The lamp went out with a report like a pistol shot. The flames alone illuminated the little room, for Ann was too numb with horror to shift from her position of relative safety to reach the light switch. In the trembling glow of the fire, the bird awakened to a new frenzy. It threw itself about the room like a gigantic bat, croaking, squirting its shit, one moment hanging in the heavy curtains as though trapped with the moths and the craneflies, then achieving a series of laboured beats across the floor which ended in a panic-stricken collision with the pictures on one wall and the light shade which dangled from the centre of the ceiling. Books toppled from shelves as the cormorant thrust its beak into the crevices between them. I joined Ann on the stairs. Together we watched the hysteria of the cormorant, the bird which had been neatly delivered to us in its clean, white box. Even when it became calmer, the collapse of another log from the fire and its accompanying shower of sparks would set it mad again. It found the cat under the sofa and struck at it twice with its beak of black horn. For a second, it held tight on the cat’s foreleg, catching it with breathtaking speed as the cat made its instinctive, raking defence, but the animal tugged free and was up the stairs, between our legs, as quick and as hot as one of the sparks from the fire. The bird worked out its anger and puzzlement in the living-room of our cottage while we could only watch, while the cat was hiding, wild-eyed, in the darkness of an upstairs cupboard, while the baby awoke and whined in confusion at the cries and the clattering impact of the struggle below, while another night of drizzling cloud descended on the mountains. The flames of the fire had their cosy, orange light shredded and shattered into a thousand splinters of red and green by the heavy, black wings of the cormorant. It spat out its guttural shouts. It splashed the walls and the books with its gouts of shit. It made threatening forays to the stairs, where I cursed and lashed out with my slippered foot. It wondered at the glowing logs, retreated from a power it did not understand and could not intimidate.

Until, exhausted as much by its unmitigated bafflement as by its assault on the incomprehensible surroundings, it staggered suddenly and toppled into the upturned crate. The bird buried its head in the familiarly scented straw, heaving with tension and fatigue.

I stepped quickly from the shadows, righted the box and replaced the lid. The cormorant shuffled into the drying straw. Then it was quiet. Its panting breath sent up fumes of fish through the perforations. I sat carefully on the sofa, avoiding the stains. Ann was weeping softly on the stairs, the tears which collapsed into the corners of her mouth catching the golden lights of a dying fire.

*

The cormorant had been left to me and Ann in the will of my uncle. Uncle Ian was a bachelor, who had spent all his working life as a schoolteacher in Sussex. For him, the narrow confines of the country prep school and all the trivial politics of the staffroom were a prison from which he could joyously escape in the holidays on his wooden river-boat. He kept the boat on the tidal mudflats of the Ouse at Newhaven. It was afloat for only four hours at a time, but he could safely reach the county town of Lewes up the river, have a meal and a pint of the local bitter before swooping back towards the coast on the retreating tide. He made this voyage innumerable times, never tiring of the flat fields which stretched away on either side of the river, never wearying of the gulls and swans and herons which maintained their posts at the slow bends and reed beds. In the summer, the swallows and martins spun their dizzy aerial threads around the little boat. A sandpiper fled upstream and waited on the next flat of drying mud before whistling plaintively and fleeing once more from the intrusion of the rippling wash. At Piddinghoe, the sun caught the golden fish which is the weather vane of the village church and threw its reflection into the brown water. There were coot and moorhen among the reeds from which the heron raised its dignified head. In the autumn, Ian went upstream in the shrinking evenings and saw a tired sun extinguish itself behind the gentle barrier of the downs.

But it was on one of his rare winter journeys that he came across the cormorant. At first, in the failing light, he thought there was a clump of weed floating in midstream, and he had steered away to avoid catching it in his propeller. But, as he passed and saw that the dark mass in the water was a stricken bird, he turned and came in close. The cormorant, a first-year bird, was drowning. It had spread its wings in an attempt to remain afloat a little longer, but soon it was waterlogged, and the swirling tide simply turned it and stirred it, and the creeping cold was deep in the bones of the young bird. There was oil on its throat and in its face. When Ian lifted it carefully into the boat, he saw that the oil was in its wings, locking together the feathers. The cormorant was trying, with its failing strength, to preen the filthy oil from its breast: in doing so, it had swallowed it and gathered it in globules around its beak. The bird lay in the cabin of the boat and rested its black eyes on the boots of the man who had plucked it from the Ouse. It was a tough young creature. It responded to Ian’s ministrations, his cleaning and feeding. Where it had at first been passive, it grew demanding and rude, aiming its murder-beak at the hands of the old man who proffered fish and meat. By the spring, it was as arrogant and vicious and unpredictable, as preoccupied with the business of eating and shouting and shitting as any first-year cormorant. Ian doted on the bird. It seemed to him to have many of the characteristics of his colleagues in the staffroom and the pupils that he taught, yet without the hypocrisy which threw up a veneer of good manners. The cormorant was a lout, a glutton, an ignorant tyrant. It affected nothing else.