0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

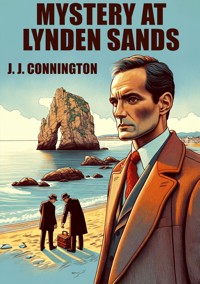

- Herausgeber: Librorium Editions

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

MARK BRAND turned into the door of an Oxford Street office building, past the indicator-board which bore: “THE COUNSELLOR, Second Floor,” among the names of other concerns. He was a shade below middle height, wiry, quick-stepping, with a sparrow-like alertness; and his taste in fabrics favoured the louder varieties for his clothes. There was a hint of raffishness about him, a faint indefinable air of horsiness, though he seldom attended a race-meeting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE COUNSELLOR

J. J. Connington

© 2020 Librorium Editions

All rights reserved

Contents

Chapter 1 | Chapter 2

Chapter 3 | Chapter 4

Chapter 5 | Chapter 6

Chapter 7 | Chapter 8

Chapter 9 | Chapter 10

Chapter 11 | Chapter 12

Chapter 13 | Chapter 14

Chapter 15 | Chapter 16

Chapter 17 | Chapter 18

Chapter 19 | Chapter 20

Chapter 21

_______________

Chapter 1

Adviser in General

MARK BRAND turned into the door of an Oxford Street office building, past the indicator-board which bore: “THE COUNSELLOR, Second Floor,” among the names of other concerns. He was a shade below middle height, wiry, quick-stepping, with a sparrow-like alertness; and his taste in fabrics favoured the louder varieties for his clothes. There was a hint of raffishness about him, a faint indefinable air of horsiness, though he seldom attended a race-meeting.

In his young days, his grandfather— a plain-spoken old gentleman who kept his carriage— had once glanced at him, grunted disapprovingly, and then declared: “That child looks like a stable-boy who’ll never grow up into a coachman.” And the family, accustomed to the awful dignity of the coachman caste, had agreed that Mark could never hope to reach that standard. This, however, proved of small importance; for Mark Brand, widely known as he was, had never appeared in the public eye. He was, to his host of admirers, only a disembodied voice.

Disdaining the lift, he ran upstairs with the swiftness of a terrier and reached the second floor opposite a door ornamented with a brass plate bearing the inscription: “THE COUNSELLOR. No appointments.” Along the corridor to the left was a plain door. Mark Brand opened this with a Yale key and let himself into his private office.

Though it was the smallest of the seven rooms in the suite, it was bright and airy; and the sparseness of the furnishing made it seem almost spacious. Three comfortable chairs, a Persian rug, a fire-proof safe, toilet fittings behind a curtain, a cupboard, a set of expanding bookshelves crammed with works of reference and other books, and a big roll-top desk: these were the main items. The desk had a telephone with a switchboard panel; and on the desk itself lay a small pile of neatly-docketed papers, and two wire trays.

Whistling softly to himself, Mark Brand hung up his oyster-grey felt hat and took the chair at the desk. He picked up the first set of documents from the pile and glanced at the typewritten slip which was clipped to them.

“My employer is too familiar, but I can’t afford to lose my job.— PERPLEXED IVY.”

This, supplied by the office staff, gave the gist of the letter to which it was fastened. Mark Brand flipped over the sheets of the epistle with a faint frown on his face.

“Better see what Sandra’s got to say,” he concluded, putting the documents into the right-hand wire tray and turning to the next set.

“What about Urisk next week?— PRESS-A-BET PETER. (N.B. Mr. Shalstone’s opinion attached.)”

Mark Brand did not trouble to read the expert opinion on Urisk’s form. All racing problems were in the hands of Mr. Shalstone, a University don known among his colleagues as the Student of Form, from his all-embracing knowledge of the proper handicaps for even the most obscure outsiders. It was his hobby. He boasted, perhaps truly, that he had never made a bet in his life; but he was not averse to drawing a liberal salary from The Counsellor, so long as his name was not disclosed. Press-a-bet Peter’s inquiry joined that of Perplexed Ivy. Both had a wide human appeal, in the Counsellor’s judgment. He picked up the next document.

“When I sunbathe, I get a rash. But if I don’t sunbathe, I am out of it.— TROUBLED.”

An almost superfluous note explained that the writer was “(female)” and added: “Doctor’s opinion attached.” This physician had once practised in the Harley Street neighbourhood, but had been struck off the Medical Register for reasons quite apart from his professional competence. He was now glad to put his experience at the disposal of The Counsellor for something much lower than his quondam fees.

Mark Brand pencilled: “Send her the doctor’s note” on a blank space on the typewritten slip and tossed the documents into the left-hand tray. His public would not be thrilled by that subject.

“Someone has palmed a bad pound note on me. What can I do with it?— CHEATED.”

The Counsellor jotted down a memorandum: “Ask him to send it to us for our museum,” and dropped the papers into the left-hand tray.

“My fiancé objects to my going alone on a cruise.— ZENA.”

This went into the right-hand tray on the strength of the epitome alone. That type of problem interested people, whether they went themselves on cruises or stayed at home. Also it was the kind of thing which lent itself to expansion into fields of wider application.

“I have an inferiority complex which goes against me at the office.— HARASSED CLERK.”

“Poor devil!” sympathised The Counsellor, as he read the letter. He put it into the right-hand tray, after scribbling a note: “Write him a kind letter and enclose Leaflet D. 7.”

“My wife re-reads her late husband’s love-letters.— K.T.”

“A polygon of a problem,” mused The Counsellor, “so many sides to it.”

He put the papers back for further consideration and continued to work his way down through the pile, sorting out the sheep from the goats, and occasionally making jottings on the typed slips. When his task was completed, he ran through the contents of the right-hand tray again, paying special attention to some of the letters. Then, for a time, he leaned back in his chair, pondering over the problems raised by his correspondents.

At twenty-two, Mark Brand had been left an orphan with no occupation except to look after a large fortune which he inherited from his father. He had tried spending his income in one way and another, but the process soon bored him.

“It’s no good” he confided ruefully to a friend. “I can’t spend even a mere £5,000 a year on myself and get direct personal enjoyment out of it. I’ll have to look for a job. And I don’t want to pile up more money. Stiff proposition.”

A chance visit to America solved his problem. Listening to the WOR station on the wireless, he heard the talks of that peculiar genius who calls himself “The Voice of Experience.” Mark Brand made inquiries, learned something about the thousands of letters which flow in to V.O.E. daily, about the office staff which copes with them, about the books, the pamphlets, the questionnaires, and about the Charity Fund.

“This fellow’s doing fine work,” was Brand’s conclusion. “We could do with something like it in Europe. Cost big money to start it. But I’ve got the money. And it must be great fun. I’ll take it on. But he’s got the best pseudonym possible. I’ll have to think of something else.”

And, from such musings, The Counsellor was born.

In one respect, Mark Brand possessed an essential gift for his self-chosen task. He had a perfect broadcasting voice: clear, expressive, and sympathetic.

And he had also what his friends called “a most infernal curiosity,” though he himself preferred to describe it as a deep interest in his fellow-creatures. The rest was merely a matter of spending money and building up a rapidly-increasing staff fit to cope with the ever-expanding demands of his rôle.

He “hired the air” for an hour each Sunday at Radio Ardennes, which formed his platform. When possible, his private plane took him over to the broadcasting studio; but when the weather made this impracticable, electrical recording served instead. Problems— social, financial, ethical, medical, legal and sporting— rained in upon him through his daily post. Those of most general interest he dealt with over the wireless, whilst the remainder were answered by letter. The demand for a sixpenny postal order with each query had hardly slackened the flood, and it served to keep the system practically solvent. The feat of which he was proudest was that once at least, like his prototype, he had prevented an impending suicide.

Begun in a modest way, The Counsellor’s business had ramified and spread like a weed. Luckily for himself, Brand had a shrewd eye in picking his staff, and a talent for decentralisation which saved him from details except when he required them. His secretarial staff attended to his enormous correspondence, passing on to him only the few letters which had the wide human interest demanded in his broadcasts. In legal affairs, pensions, and insurance problems he was advised by an ex-solicitor of exceptional talent who had been struck off the rolls in circumstances which he scorned to explain. Financial matters were dealt with by another expert; but this was a field into which The Counsellor entered rarely and reluctantly. The Problem Department supplied solutions to cross-word puzzles and the like, week by week. Applicants for its assistance had to forward a shilling postal order instead of the usual sixpenny one. To balance that, the Advertisement Department charged nothing for its services, since its expenses were borne by the firms which sought publicity through it.

The Department on which The Counsellor looked with the kindest eye— as being the one most useful to him in his broadcasts— was known unofficially in the office as Cupid’s Comer; and it was managed by a girl who had got engaged just before she was appointed to it. It was well understood that as soon as she married, her post would fall vacant; for, as The Counsellor said, the sympathetic touch was essential in that branch of his business.

After having considered the problems presented by his morning mail, The Counsellor extracted one document from the set and pressed a bell-push concealed under the edge of his desk. The door of the adjoining office opened and his private secretary appeared, notebook in hand.

“Morning, Sandra,” The Counsellor greeted her, with his friendly smile. “No, no dictation just yet. I want your views on this, first.”

He picked up Perplexed Ivy’s epistle and flipped it across the desk.

“Glance through it, and see what you think.”

Miss Rainham sat down and spread out the letter on her knee. She was chestnut-haired, clear-eyed, alert, and twenty-four. She looked her age, neither more nor less. People spoke of her as charming and unconsciously avoided such adjectives as capable, competent, and efficient. She merited them, but they did not express the more obvious side of her personality. Her good looks were sufficiently above the average to allow her to take them for granted, which perhaps had something to do with her charm.

“Well?” demanded The Counsellor, as she glanced up from the letter with a faint frown.

“Not a very nice case, is it?” retorted Miss Rainham. “The man seems to be worrying her badly, and she’s got this invalid mother depending on her.”

The Counsellor nodded.

“He’ll chuck her out without a character, if he doesn’t get what he wants; and that would leave her and her mother stranded,” he commented unnecessarily.

“I might see her,” Sandra Rainham suggested tentatively.

“It’s a well-written letter,” The Counsellor said, critically. “You’d better see her. Don’t bring her here. Take her to some teashop. You can pick her brains in no time, if she’s what the letter looks like.”

“And then?” Sandra demanded. “No good seeing her, unless we can do something, is there?”

“Trouble is, she’ll need some sort of reference, to get another post. If she’s all right, it’s easy. Tell her to chuck her present job. We’ll take her on here for a few weeks at the same screw. After that, she’s got us behind her when she looks for other work. She can enclose circulars with letters, or something like that. But make it clear that we aren’t an Old Age Pension.”

“She might turn out to be efficient; and we’re going to lose two of our girls very shortly,” Miss Rainham suggested.

“I remember that. Let me know in time to order the cutlery canteens.”

A complete canteen of cutlery was The Counsellor’s invariable wedding-present when any of his staff got married. These things were always useful and his method saved him the trouble of selection.

“No promises to this girl,” he added with finality. “I’m not a charity.”

The secretary smiled as she bent her head to jot down the girl’s address. If Perplexed Ivy proved satisfactory during her probation, Sandra would see that she got a permanency. She had liked that letter.

“I’ll see her and report,” she said.

Sandra Rainham had been one of The Counsellor’s “finds” when he began to gather a staff. She was a distant relation, a third cousin once removed cr something equally remote, left at her parents’ death with just enough money to exist on and a fund of energy which demanded some useful outlet. The Counsellor had seen in this girl of twenty the sort of material he needed; and after putting her through an expensive technical training, he had engaged her as his private secretary. Private secretary she remained in name; but actually she and Wolfram Standish, The Counsellor’s manager, jointly controlled the more mechanical side of the ever-expanding office work. Like The Counsellor himself, she was “interested in humanity”; and in that office an interest in humanity implied an equal keenness in the working of the intricate system. It suited her. She satisfied The Counsellor who, though generally easy-going, was apt at times to develop inquisitiveness about details, which was his way of keeping his finger on the pulse of the business.

The Counsellor picked up the packet of documents from the right-hand tray, and at that signal Miss Rainham opened her notebook. This was the serious stage of The Counsellor’s activities: the making of a rough draft of his next wireless talk from Radio Ardennes. He dictated slowly, with occasional pauses for thought, a shrewd and helpful series of answers to the selected letters, spiced with a dry humour which made his points tell. His style “on the air” was different from his normal snappy sentences, but it had an incisiveness of its own.

He had almost finished his dictation when an office-boy entered with a letter. As The Counsellor took it, he noted the broad vertical line on the envelope.

“Express Delivery? Somebody in a hurry, apparently. Just wait a moment, Sandra.”

He opened the envelope, drew out the letter, and glanced through it. Then, dismissing the boy, he turned to his secretary.

“Rum go, this. Have a look at it.”

He pushed the letter across the desk to Sandra. She glanced at the heading: ‘‘THEIR RAVENSCOURT PRESS, Longstoke House, Grendon St. Giles,” and her eyebrows lifted slightly as though in surprise. Then she began to read the letter itself.

9th September, 1938.

Dear Sir,

I venture to ask for your assistance, since you have facilities for getting in touch with people all up and down the country. As a guarantee of good faith I may mention that I am one of the experts employed by Mr. James Treverton, of the Ravenscourt Press; and I have his permission to approach you in this matter.

The facts are as follows. On 8th September, Miss Helen Treverton (Mr. Treverton’s niece) set off in her car, intending to visit Dr. and Mrs. Trulock, who live a few miles away and who were giving a small garden party that afternoon. She did not return for dinner; and when inquiries were made, it was found that she had not gone to Dr. Trulock’s house, as she had meant to do.

Up to the present, she has not returned home, and nothing has been heard of her. No message of any kind has been received from her. She seems to have disappeared completely.

I have Mr. Treverton’s permission to ask you to help. Could you, in your broadcast next Sunday, ask if anyone has seen a brown Vauxhall 12 h.p. saloon, with the number EZ. 1113? Some of your numerous listeners may have happened to notice it. Your assistance may be invaluable.

Yours faithfully,

WALLACE WHITGIFT.

“Think it’s a leg-pull?” demanded The Counsellor, with a shrewd glance at the girl’s face as she finished her perusal. “We’ve had attempts before this, though they didn’t come off.”

Sandra shook her head.

“Hardly likely,” she decided. “I’ll ring up the Ravenscourt Press and get hold of Mr. Treverton, just to make sure. Funny. It was only last week that I bought one of these Ravenscourt reproductions.”

“Good stuff, are they?” inquired The Counsellor. He had no interest in reproductions of the old masters, preferring to buy the work of the younger modern artists to whom sales meant encouragemert.

“Amazingly good,” Sandra assured him. “They beat anything else on the market when it comes to accurate reproduction of tints; and they’ve got some special paper as a basis which seems to help. Of course, they’re not cheap. But they’re worth the money to me.”

She passed Wallace Whitgift’s letter back to The Counsellor and added:

“If it’s all right, I suppose you’ll put it in the broadcast?”

“If it’s all right,” admitted The Counsellor. “But just ask a question, Sandra.”

Miss Rainham smiled rather wearily. She knew that last phrase only too well, for it was one of The Counsellor’s favourites.

“Well, what question?” she inquired.

“Why does Mr. Wallace Whitgift— who seems to be some sort of employee— butt into this business at all? Why didn’t Uncle James write to us himself? Strange, eh?”

“That’s three questions instead of one,” Sandra pointed out. “I can guess the answers. First, Mr. Whitgift may be one of your fans. That would account for his turning to you. Second, Mr. Treverton may never have heard of you. Sorry, Mark, but it’s a fact that quite a number of people don’t know you exist. And if he never heard of you, he probably doesn’t think you’re likely to be of much use. So he lets Mr. Whitgift take the responsibility of raking you in. On that basis, the answer to your third question is: “Not at all.” And, finally, Mr. W. is not just “a mere employee.” He’s a director of the Ravenscourt Press. Also, he’s their expert in the actual reproduction processes. I know that from reading their catalogues.”

“Doesn’t account for his butting in like this,” objected The Counsellor.

“Oh, well, just ask a question,” Sandra parodied. “Is Wallace Whitgift keen on this girl, by any chance? If so, that might account for his zeal.”

“I never butt into our Cupid’s Corner Department,” retorted The Counsellor with dignity. “Still, it’s a rum start: total disappearance of a car with a young damsel inside. Cars get stolen, and girls disappear at times. But they don’t usually vanish in pairs. A car’s fairly identifiable; and when you add a girl to it, it becomes positively too conspicuous to grab easily.”

“What makes you think she’s a young damsel?” asked Sandra drily. “I’ve known nieces of forty-five and upwards.”

“In that case, Wallace wouldn’t be very keen on her, one might suppose. Have it one way or the other, but not both ways at once.”

Miss Rainham became businesslike.

“I’ll put through a trunk call and speak to Mr. Treverton,” she proposed. “Then, if he makes no objection, you’ll put this into the broadcast tomorrow?”

“Yes. No harm in that. And now I’ll give you the rest of the stuff for it.”

He resumed his dictation. When this was completed, Sandra Rainham closed her notebook and left the room. She came back again sooner than The Counsellor had expected.

“I managed to get through fairly quickly,” she explained. “It’s all right, apparently. The girl hasn’t turned up yet. Mr. Treverton has no objection to your broadcast, so you can go ahead.”

“He’s worried, I suppose?” inqfuired The Counsellor.

“Not particularly, so far as I could make out,” Sandra replied in a faintly puzzled tone. “It almost sounded as if he thought Mr. Whitgift was making too much of a fuss about the business. There was a suggestion of ‘Let ’em alone, and they’ll come home... ’ about his tone; as if a mislaid niece was a thing that might happen to anyone now and again. Even over the ’phone he doesn’t sound a sympathetic character, somehow.”

“How d’you mean, exactly?”

“Well, he talks as if he were thinking of something else, all the time he’s speaking. I can’t get nearer than that. Nothing of the distracted relative about him.”

“You think so? Well, anyhow, we’ll shove it into the broadcast. Just take this down, please.”

He dictated a further note.

Chapter 2

At Grendon St. Giles

ON THE FOLLOWING Monday morning, The Counsellor arrived punctually at his office and spent some time over matters of routine. But his heart did not seem to be in the business; and when it was completed he turned from it with relief, and rang for Sandra Rainham.

“Broadcast all right?” he demanded, as she entered the room.

It was one of her duties to listen to Radio Ardennes when he was speaking from the station and to supply him with any criticisms which occurred to her.

“Quite,” she answered, “except that you’re growing inclined to drop your voice at the end of sentences. You’d better watch that.”

“Right! By the way, have any wires or letters come in about that missing car?”

Sandra shook her head.

“Nothing, so far. Monday’s not usually a busy day for correspondence. Even if they write on Sunday, it doesn’t get here till the afternoon, you know.”

The Counsellor conceded this with a nod. Then he pushed the switch of his desk-telephone over to “RECORD DEPARTMENT” and picked up the transmitter.

“Records? Go through the Sunday papers— yesterday’s, I mean— and see if there’s anything about a girl disappearing last week from Grendon St. Giles. Also, see if we’ve had any correspondents in that place.”

The Counsellor was proud of his Record Department, and especially of its filing system. “Any fact in fifty seconds” was his boast about it, though this estimate was regarded as optimistic by Miss Rainham and others of the staff. On this occasion it was considerably under the mark. A girl cannot scan all the Sunday papers in fifty seconds. However, in a remarkably short time he got his answer. There was nothing in any of the Sunday papers about the disappearance; but in Grendon St. Giles there were two clients of The Counsellor. He picked up the notes which Records handed in.

“Our esteemed correspondents in Grendon St. Giles. Mrs. Sparrick. Anxious about her daughter’s choice of a fiancé. Advised, with satisfactory results. Not much help there. Aha! Inspector Owen Pagnell of the local police. I remember that business. We helped him. Broadcast some message that couldn’t well be put through official channels. He’ll be handy, if he’s got any sense of gratitude.”

“Why all this interest?” demanded Sandra Rainham. “What’s it got to do with you?”

“ ‘I am a man, and nothing human can be foreign to me,’ ” quoted The Counsellor. “Aristotle said that, or was it Polybius?”

Miss Rainham had been as well educated as Mark Brand, and she had a better memory for quotations.

“Terence,” she corrected acidly.

“Oh, well, it doesn’t matter. Good man, whoever he was, I expect,” averred The Counsellor, quite unabashed. “I’ve just been thinking of taking a hand in that affair about the girl. Helen Treverton, I mean. The one who disappeared last Thursday. I’ve often wanted to probe a mystery and all that sort of thing.”

“You’ve been reading too many detective stories,” Sandra decided, not without some basis for her judgment.

“Well, what else is there to read, nowadays?” demanded The Counsellor, fretfully. “Everybody’s doing it. I have to keep in touch with the Great Heart of the Public. It’s essential to my work.”

“I’d leave it alone, if I were you,” said Miss Rainham in a decided tone.

“You don’t sound encouraging, and that’s a fact,” complained The Counsellor. “If you feel like that, then we must find support elsewhere. We’ll try Standish.”

When The Counsellor began to build up his staff, he found his manager in his own circle. Wolfram Standish was a couple of years younger than Mark Brand, but they were old friends and suited each other. The manager’s rather impassive face, cool manner, and slightly bored drawl made him a perfect foil for the volatility of his chief.

“This is how it is, Wolf,” The Counsellor jerked out as Standish came into the room. And in a few illuminating phrases he laid the matter before his subordinate. Standish listened dispassionately. Then, when The Counsellor had finished, he took out his case and lit a cigarette.

“Well, what do you think of it?” Miss Rainham demanded, with some impatience.

Standish blew out his match, examined it carefully to see that the flame was extinguished, then pitched it into the wastepaper basket.

“I don’t think anything,” he began, and Sandra’s face showed some relief until he continued leisurely, “He’s made up his mind. What’s the good of thinking?”

He paused, looked at his cigarette, and then added:

“It’s just his ‘satiable curtiosity’ breaking out again.”

Neither Miss Rainham nor Standish stood in any awe of their employer. They had known him when he was too young to expect reverence. Among themselves, The Counsellor was nicknamed The Elephant’s Child after the animal in The Just So Stories.

The Counsellor glanced from one to the other in feigned disappointment.

“You don’t seem bubbling over with enthusiasm and desire to help the young master, and that’s a fact,” he commented.

“We’ll bail you out when the police arrest you as a public nuisance,” Standish promised. “That’s always something.”

“And his tall uncle, the Giraffe, spanked him with his hard, hard hoof!” quoted The Counsellor, quite undepressed. “That means you,” he added to Standish.

“ ‘And still he was full of ‘satiable curtiosity,’ ” Sandra continued the quotation. “And that means you. Seriously, Mark, do you really mean to go down there as the complete detective?”

“Absolutely,” retorted The Counsellor. “I shall take with me all the necessaries. A hypodermic syringe, cocaine, a violin, a pound of shag, a Thorndyke research case, Sir Clinton Driffield’s copy of Osborn’s Questioned Documents, some of Mr. Fortune’s intuitive capacity in my vest-pocket, and Lord Peter Wimsey’s collection of jade— I can get that into a sack over my shoulder....”

“I see,” interjected Standish. “You’re going down there disguised as a caddis-worm? It’s an idea, certainly.”

“... and some of Poirot’s little grey cells,” The Counsellor concluded.

“That’s a sound notion,” Standish conceded. “It’ll be just as well to have some brains with you.”

Miss Rainham made an arresting gesture.

“You’ve forgotten the most important thing of all.”

“Have I. What’s it?”

“A Watson, of course.”

“Oh, that?” said The Counsellor in a tone of relief. “That’s provided for. That’s it there.”

With a jerk of his head, he indicated Standish. His subordinates exchanged a glance and then spoke in stage whispers.

“He really means to go?”

“Looks rather like it, doesn’t it? Perhaps he’ll waken up when he actually gets there.”

“You’d better go with him, Wolf. He might get into trouble, in this state.”

“Something in that. I can say his nurse let him fall on his head when he was in short clothes.”

The Counsellor ignored this by-play.

“While you’ve been chattering, I’ve been thinking,” he explained benignantly. “This is the plan. I’ll go down to Grendon St. Giles to-day, to spy out the land. I hope to clear the matter up at once. If I have to stay overnight, I take rooms at the best hotel— just look it up in the A.A. book, Sandra, please. Wolf will mind the shop here, while I’m away. If I happen to need you, Sandra, I’ll wire for you.”

“Need me?” demanded Miss Rainham indignantly. “What for?”

“Delilah, or something in that line, perhaps,” explained The Counsellor casually. “One never knows, beforehand. As to the next broadcast, I’ll get it recorded so as to leave me free.”

“Napoleonic!” Standish ejaculated in mock admiration. “What a grasp of detail. You’re starting to-day, are you, Bonaparte?”

“As soon as I can get my car round.”

Standish reflected for a moment and then began to whistle an air softly.

“What’s that?” inquired The Counsellor.

Standish changed his whistle to song:

“ ‘Malbrouck s’en va-t-en guerre,

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine,

Malbrouck s’ en va-t-en guerre,

Ne sait quand reviendra.’

It’s what Napoleon whistled as he watched his troops file over the river to the invasion of Russia,” he explained. “It seems appropriate at this solemn moment.”

“A bright and encouraging lot of helpers I have,” said The Counsellor, disgustedly. “Throw yourself into the part, Watson. Now, Sandra, let’s see that A.A. book. Heaven send there’s a decent hotel.”

“Grendon St. Giles isn’t in the list,” said Miss Rainham, with satisfaction in her tone. “There’s no hotel there at all, so far as the A.A. goes. There may be a good-pull-up-for-carmen, perhaps.”

“That being so, I shall probably return to town to-night,” The Counsellor decided, glancing out of the window as he spoke. “I see my car below. The god will now get into the machine. Ta-ta!”

During the run down to Grendon St. Giles, The Counsellor put his coming business out of his mind. He had no doubts about a successful issue. With thousands of his wireless listeners to help him, the mere tracing of an easily-identifiable car was a dead certainty. But his audience would be interested in the hunt. It would be a good advertisement for his broadcasts. And, just possibly, there might be a story behind this girl’s disappearance, something with the human touch in it. One must play the game, of course. It might not be the kind of thing for public use at all.

Grendon St. Giles, at the first glimpse, appeared as a little spire rising from among trees. On closer acquaintance, it turned out to be a pleasant little village, the cottage gardens bright with roses, a tiny village green with some spotless geese, a church with a lych-gate, and a tidily-kept inn. A glaring petrol-pump was the only jarring feature in sight.

The Counsellor picked up the speaking tube.

“Pull up at that pump,” he directed his chauffeur. “Get a couple of gallons and ask the way to Longstoke House. Then go on there.”

Longstoke House, it appeared, was a couple of miles further along the road and just beyond an A.A. telephone-box. They turned into a gate. No lodge-keeper appeared, though the cottage was evidently inhabited. A short avenue led up to the main building; and The Counsellor, who kept his eyes open, noted that the proprietor did not seem to spend much in upkeep. What had at one time been the park was now obviously let out as grazing-ground; and the gardens, through part of which they ran as they neared the house, had been allowed to run to seed. The mansion itself, when they came to it, proved to be a gaunt affair in the Rural Italian style; and its uncurtained windows reinforced the impression that the owner spent nothing on outward show. The whole place looked bleak and lifeless, except for the smoke rising from a chimney.

Telling his chauffeur to wait, The Counsellor got out and went up to the out-jutting portico of the main entrance. He had taken the precaution of wiring before he left London; and when he asked for Mr. Whitgift he was shown into a room and asked to wait for a few moments. Mr. Whitgift, it seemed, was occupied.

Judging from the size of the mansion, The Counsellor inferred that originally this apartment had been a small morning-room; but from the wholly feminine style of the furnishing it had evidently been converted into the modern equivalent of a boudoir. Its windows, unlike those in the front of the house, were curtained; the colour scheme had been chosen by someone with a good eye; and the furniture combined comfort with a certain artistry. It was obviously a room meant to be lived in. The only discord was struck by the ceiling, which had a heavy, old-fashioned decoration in stucco from the centre of which, in earlier days, a chandelier had evidently depended, for The Counsellor could see the closed end of an old gas-pipe in the middle of the design. Now the lighting was electric, by a standard lamp and a couple of pillar-lights on the mantelpiece. The Counsellor had no time for a further survey, for the door opened and Whitgift appeared.

He was a big man, rather over six feet in height, with broad shoulders and a slow gait which somehow added to the impression of physical power. Instead of a jacket, he wore a white linen coat, as though he had just come from a workroom. He came forward with a pleasant smile showing even lines of very white teeth. A good mixer, The Counsellor decided at the first glance, a fellow who would get on equally well with men and women.

“Mr. Brand? Well, I know you better than you know me, I guess. Your broadcasts, you know. It was very good indeed of you to give us your help in this awkward affair.”

His face clouded at the last sentence as though it touched some sore spot in himself. Then he recovered himself almost immediately.

“Sit down, won’t you? Cigarette? Or perhaps you’d rather smoke your own brand?”

He took a box of cigarettes from a table near by, offered them to The Counsellor, picked out one for himself and lighted it before saying anything further. Meanwhile his eyes were evidently busy with Brand’s outward appearance. It seemed to be not quite what he had expected.

“Any further news of Miss Treverton?” The Counsellor asked, as soon as he got his cigarette alight.

Whitgift shook his head despondently.

“Not a sign of her. It’s extraordinary. I can’t make it out, you know. She was a level-headed girl, not the sort of girl to fly off the handle. Nothing freakish about her, I mean.”

He went over to a writing-desk and came back with a framed enlargement of a snapshot which he handed to The Counsellor. It showed a girl in a sports coat stooping to pat a collie. She was looking towards the camera, and The Counsellor saw at a glance that she had an attractive face, with a frank smile and a dimple on each cheek. In the flesh, she must be pretty; and, judging purely from the snapshot, The Counsellor put her down as a girl of character, dependable, and not at all likely to indulge in silly pranks.

“That’s her collie with her, poor old Clyde,” Whitgift explained. “He died less than a week ago. We found him out in the fields one morning, stiff. She was immensely fond of the beast, and I guess that’s why she has the photo on her desk. I took it myself about six weeks back, the last one she had of him.”

“She wasn’t engaged, was she?” asked The Counsellor, who had noted the ringless finger visible in the picture. “Nothing of that sort to account for her vanishing?”

“No, she wasn’t engaged,” Whitgift answered with a reluctant sullenness in his tone which attracted The Counsellor’s attention. “There was an American who was keen on her at one time, but nothing came of it that I know. Querrin, his name was, Howard Querrin. Not good enough for her, I thought, and probably she thought the same.”

That sounded almost like a touch of jealousy, The Counsellor reflected. And not so unlikely, perhaps. Grendon St. Giles obviously offered little in the way of society. Whitgift must have seen a good deal of the girl, if she lived on the premises here. Add her attractiveness to the propinquity factor, and it wasn’t unlikely that he might fall in love with her. If he had, then his obvious dislike of an intruding rival, in the form of this American, was intelligible. There might be something in Sandra Rainham’s suggestion about the nature of Whitgift’s interest in the case. But that was a side-issue. The Counsellor’s present interest was in the facts of the disappearance.

“Was it her own car that she went off in?” he asked.

Whitgift nodded.

“Yes, we’ve each got a car. Treverton has an old Ford, though he seldom uses it; and I’ve got a car down at the lodge. I live there, you know.”

The Counsellor reflected before putting his next question.

“What about money? Could she lay her hands on enough to finance her for, say, a month away from home? Without asking her uncle for it, I mean.”

“Oh, yes, easily. Her father left her some capital, I believe. I know she put a fair sum into the Press when she came of age four or five years ago. We’re all in it, if it comes to that, you see. I’m a director, as well as shareholder and expert, myself. Dividends are sub-microscopic, though. She had the rest of her capital, whatever it was, in other concerns which paid better, one hopes. I don’t suppose she was rich, by any means; but she had enough to go on with, I think. Enough for a girl living here, anyhow.”

He pondered for a moment or two, then added reluctantly:

“I believe she and her uncle.... Well, there’s been some faint friction because lately she talked of taking her cash out of this concern. But that’s between ourselves, of course.”

“I’d like to hear just how she came to disappear,” said The Counsellor.

“I can tell you what I know myself, but that’s not much. Last Thursday morning, I had to go into Grendon St. Giles on an errand. My own car was scuppered at the moment, something gone wrong with the pump; and it was at the village garage getting fixed. That was a blazing day, you remember, and I didn’t cotton to tramping four miles through it. Miss Treverton offered to take me in. She’d some things she wanted herself.... By Jove! I never thought of that!” he ejaculated. “It was your mentioning cash that brings it back. She called at the bank while I was doing my own bits of business.”

He seemed impressed by this recollection.

“The bank could tell us how much she drew,” he suggested.

“Banks don’t babble about their customers’ affairs,” said The Counsellor, impatiently. “The counterfoil of her cheque book’s all you want. Time enough for that. Go on with the story.”

“All right,” agreed Whitgift, though he seemed to keep the point at the back of his mind. “We came back here. She put her car into the garage because the sun was so hot that it would have been bad for the tyres to leave it standing about. Just as she was switching off, I happened to look at the petrol-gauge and saw her tank was empty, almost. We keep a stock of tins in the garage, just for that kind of emergency, so I pointed out the state of things and offered to fill up her tank for her while she went over to the house. I filled it full, and then came back here myself. That was before luncheon.”

“Yes, yes,” said The Counsellor. “Your point is that she started off in the afternoon with a full tank. I understand.”

Whitgift nodded and continued:

“That afternoon, as I told you in my letter, some people Trulock were giving a kind of garden party, of sorts, and Miss Treverton was going to it. Treverton wasn’t going; he hates all that kind of thing. The Trulocks live about eight miles away and she was going over in her Vauxhall. As it happened, I’d had to go down to the lodge about three o’clock to get a document I’d left in another suit, and I met her with her car as I was coming up the avenue again. I stopped her and told her about having filled her tank, and I saw her glance at the gauge. We said a few sentences to each other, but I can’t remember what they were— just commonplaces about the tennis-party, wishing her a good game, that sort of thing, you know. Finally she drove off, and that was the last I saw of her. That was almost exactly at three o’clock. I know that, because a bus passed the lodge gate while we were talking, and it’s timed to reach Grendon St. Giles at five past three. That’s the last I saw of her,” he repeated.

Something in the tone of his voice betrayed an anxiety which hitherto he had apparently striven to keep under control.

“How was she dressed, then?” demanded The Counsellor, more concerned to pick up information than to trouble about Whitgift’s feelings.

“A light grey coat and skirt, but it’s no good asking me what the material was. I know nothing about girls’ clothes. She was driving over, dressed like that. But she was going to play tennis. She had her racquet in its press on the seat beside her, I noticed; and she had an attaché case, too, with a tennis shirt and shorts and tennis shoes in it, I suppose. She meant to change when she got to the Trulocks. So I suppose, anyhow. There’s quite a good court at the Trulocks’ place, I’m told. I’ve never played on it, though. I’m not more than a nodding acquaintance of Trulock.”

“And what happened after this?” asked The Counsellor.

“Nothing. She didn’t come home, that’s all. I told you the rest in my letter, about my getting anxious and ringing up the Trulocks. She hadn’t arrived there, they said. Apparently they took it that she’d got a headache or something like that and hadn’t felt up to going over, and they expected that she’d ring up and explain later on. They’d had enough people there to make up their sets, so they hadn’t bothered to ring her up and ask why she’d given them a miss.”

“Yes, yes,” said The Counsellor. “And when did you begin to get anxious about her?”

“Not till about midnight,” Whitgift explained. “I thought perhaps they’d got up a scratch dance or something and that she’d stayed on for that. It was a hot night, you remember, and I’d been sitting out in a camp-chair at the lodge, trying to get cool, so I knew she hadn’t come home. Naturally I began to get a bit worried, so I came up here, got in with my latch-key, and rang up the Trulocks.”

The Counsellor had a picture in his mind’s eye of this big man sitting out in his garden in the gathering dusk, watching, watching for the return of that car, with anxiety growing as the clock crept on. Had Whitgift proposed to that girl and, despite a refusal, kept some hope alive of her changing her mind? Or was it that he hadn’t enough money to make a proposal reasonable? That passing remark about the finances of the Ravenscourt Press might point in this direction. And that, too, might account for the jealousy in the matter of the American.

“Mr. Treverton hadn’t become anxious when his niece failed to turn up?” asked The Counsellor.

“Apparently not,” Whitgift confessed. “I woke him up when I got the message from the Trulocks, but he wasn’t exactly grateful. He came to the door of his room and grumbled at being disturbed. The girl was old enough to look after herself, and that sort of thing. Between ourselves, you must remember that there had been that friction between him and Miss Treverton over the matter of the money she has in the business, and perhaps that didn’t make him very sympathetic. He’s... well... a little peculiar in money matters.”

“Is he?” inquired The Counsellor, without apparent interest.

“He’s a queer mixture,” Whitgift declared. “Now, when we took over this house for our work, there was no current laid on. It had been empty for years; and the Grid hadn’t reached out to here when it was last inhabited. What they’d used was acetylene gas. There’s a generator in the stables. That was no good to us, of course, so the plant was scrapped and we got in the Grid current. But tearing out the old acetylene piping would have cost some money— not much— and Treverton absolutely refused to spend a penny on that. You can see the piping still in place up there. And most people would have pulled down all this ghastly stucco ornamentation and made a plain plaster ceiling, just to get rid of these eyesores in every room. He wouldn’t, although it could have been done cheap enough, and he’s got an artistic eye which must make him gulp every time he sees one of these abominations. That looks as if he’s mean, doesn’t it? Well, he isn’t mean when it comes to the Press. We’re a very small company working on on a mere mite of capital, and naturally we run up bills which we often can’t pay. If we do, Treverton steps in, foots the bills out of his own pocket, and never thinks of charging that up to the company. A man who does that kind of thing isn’t really mean, as you can see for yourself. It’s simply that with him the Press comes first and foremost all the time, though he grudges money in every other direction.”

“‘Art’s a rum job,’” quoted The Counsellor. “Turner said that, and he ought to know. And humanity’s a rum crew. I said that, and I happen to know. When you mix ’em together, anything might happen. I’m not surprised.”

He seemed to cogitate for a moment or two and then turned to a fresh line.

“Has Miss Treverton any other relations beyond her uncle?”

“None that I ever heard of,” Whitgift answered, after a moment’s reflection.

The Counsellor did not pursue that subject. If anything had happened to the girl, and she died intestate, her uncle would get not only the money she had in the business, but the remainder of her capital as well. But this seemed pushing hypothesis over far.

His eye was caught by a picture on the wall, and he moved over to examine it.

“Monet’s ‘Corniche Road,’ isn’t it?” he asked, turning to Whitgift. “Is this one of your own productions?”

Whitgift nodded in confirmation.