3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Post Mortem Press

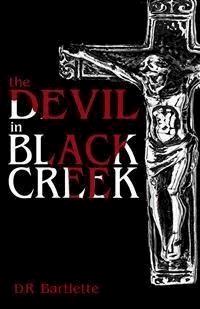

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

1986 is the year everything blew apart … Twelve-year-old tomboy Cassie lives a pretty boring life in small-town Black Creek, Arkansas, until her mom and dad divorce, throwing her into poverty and shattering her sheltered life. Then the rich, elderly Henson sisters take pity on her, taking her under their wings and into the church. Except the handsome, charming new preacher has something strange going on in his shed. When Cassie starts snooping around his property looking for her lost dog, she discovers something so awful, no one will believe her – and that may put her own life in danger.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

THE DEVIL IN BLACK CREEK

A Throwback Novel of Small Town Suspense

D.R. Bartlette

POST MORTEM PRESS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

PART II

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

PART III

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

PART I

CHAPTER 1

1986 WAS THE YEAR EVERYTHING blew apart: the space shuttle Challenger. Chernobyl. My family. And finding that boy’s bones in Little Diamond Lake.

It started in late January, our fourth week back after Christmas break. It was second period, English. We were doing worksheets on commas when Principal Holt, his voice shakier than usual, announced, “All students and faculty are to report to the cafeteria immediately.”

I piled out of the dingy little trailer with the other seventh graders into the chilly, bright day. We shuffled past the football field, under the cold shadow of bleachers, the giant scoreboard towering over everything.

In just a few more steps, we were at the Black Creek Middle School main building, a tan cinderblock box with narrow windows set high up on the walls like a prison. Inside, the cafeteria was packed with my seventh-grade class plus the sixth and eighth graders – probably a hundred kids all together – milling around, trying to find their friends and not act worried about why we’d all been called out of class so suddenly. On the stage was the AV cart with the TV strapped to the top. Mr. Holt and Vice Principal Bradley were next to it, fiddling with the wires. They finally got it going, and there was Dan Rather’s somber face on the screen.

A sharp “Shhh!” went through the crowd as the image switched to the space shuttle Challenger climbing higher and higher into the clear blue sky, a river of fire trailing behind it. Then, in the blink of an eye, the fire caught up with the shuttle, devouring it. There was a great, bright flash and then not one, but two trails of smoke veering wildly in the sky.

At first, I didn’t quite understand what I was seeing. But all around me I could hear gasps and soft yelps of surprise. I moved towards the stage, straining my ears to hear Dan Rather. As images of the now-dead astronauts flashed on the screen, my mouth hung open, too surprised to make a sound. I looked behind me and saw Mrs. King, my English teacher. She stood still, her arms crossed in front of her chest, tears running down her cheeks.

After a few minutes, Mr. Holt finally turned off the TV and led us all in prayer for the souls of the brave astronauts—especially Christa McAuliffe—and to comfort their families and loved ones. I bowed my head and said “Amen,” kind of in shock.

They let us out early. There was no way, Mr. Holt said, that anyone could be expected to concentrate after such a tragedy.

That evening, I only went inside the house long enough to drop off my backpack. Mama and Daddy were arguing again, and I didn’t want to be anywhere close enough to get sucked in and forced to choose sides. So I went outside to play with Sheba. I petted her wide black head and scratched behind her floppy ears—she was too small, the breeder had said, for a pit bull, so they hadn’t bothered docking her tail or ears. She shook from nose to tail, rattling her heart-shaped dog tag and sending up a cloud of short black fur. We played fetch the stick until it got too cold to stay outside.

Inside, Mama was standing over the stove, the smell of Shake-N-Bake pork chops and Hungry Man potatoes swirling around her. Her normally perfectly made-up face was smudged, her eyeliner smeared. She held the spatula and her Eve cigarette in one hand; the other was folded tight across her trim waist. Still holding the cigarette, she set the spatula down, picked her vodka and cranberry juice off the counter and brought it to her lips, leaving a mauve lipstick stain on the glass. She was fixing Daddy’s dinner, though he was nowhere to be seen. Her dinner, and what she’d make me to eat too, was on the counter by the fridge: salad and steamed chicken breast. Gag me.

Dinner was tense. Daddy wasn’t at the table. Probably in the guest room, I figured. He seemed to spend a lot of time in there lately. I sawed my way through the tough, stringy chicken breast and tried to avoid Mama’s attentions. I sat up straight, ate only tiny bites, kept my mouth shut and my elbows off the table. It almost worked.

“Push your hair back from your face,” Mama said, the ice clinking in her vodka and cranberry juice. I did. She saw me eyeing Daddy’s dinner. “You shouldn’t eat that stuff, you know,” she said, pointing at his plate with a forkful of iceberg lettuce and fat-free ranch dressing. I dropped my head so she wouldn’t see me roll my eyes. “It’s fattening. You may be thin now, but if you keep eating fat food, you’re going to get fat.”

“Yes, Mama,” I said. It was the only thing I could say to her, really.

After being excused, I went into the living room and switched on the TV, even though I didn’t really want to watch anything. I just liked having the sound as a distraction. The nightly news came on, more talking about the Challenger disaster. Then near the very end of the broadcast, they told about a missing boy from Fayetteville, the closest city to Black Creek. His name was Jason Jared Moore and he was ten years old. They showed his picture, a chubby kid with curly dark hair and blue eyes. He’d been a “latchkey kid,” and when his mama came home from work last night, she’d found him gone. Fayetteville was a ways away—about thirty minutes’ drive—but it still sent a chill through me. I looked back into the kitchen and could see Mama bent over in front of the fridge, digging out more cranberry juice, and consoled myself that I’d never be a latchkey kid. Mama wasn’t the type to work.

The next morning, things seemed back to normal. Daddy was in the kitchen in his work clothes drinking his coffee when I woke up. Mama was still in bed, thank God. If she was awake, she’d find something wrong with my outfit or my hair and make me go back and fix it so I’d look “presentable.”

I stood at the entry to the kitchen and leaned against the wall, just watching him. I liked watching Daddy because it seemed like it was getting rarer and rarer that he was around. He was standing over the counter, six feet of him, in his yellow suede work boots and blue jeans. His copper-penny hair—same color as mine—fell just past the collar of his blue work shirt.

“Mornin’ Cassie,” he said.

“Mornin’ Daddy.” He handed me my lunch money and kissed the top of my head, his bristly moustache catching some of my hairs and pulling them out of my ponytail. “Be good at school,” he said.

“I will,” I said, and hugged him hard. I pulled on my favorite jacket and headed out the door so I wouldn’t miss the bus.

On the bus I sat behind Jeremy Roscoe, the oldest of the five red-headed Roscoe kids who live at the bottom of the hill. He should have been in seventh grade, same as me, but he got held back last year. He turned around and stood on his knees to face me, a big shit-eating grin on his freckle-splattered face. “What color were Christa McAuliffe’s eyes?” he said.

“I don’t know.” This close, I could see drip of bright green snot on the edge of his nostril.

“Blue!” he said. “One ‘blue’ one way, one ‘blue’ the other!” He let out a laugh like a donkey snort.

“You’ve got snot on your face,” I said.

He responded by flipping me the bird and sticking his tongue out before turning to Tanya Peterson across the aisle: “Hey, what color were Christa McAuliffe’s eyes?” By the time school let out, everyone was telling that joke.

CHAPTER 2

WHEN I GOT HOME THAT afternoon, the sun was bright and warm—one of those odd late winter days that teases you, fools you into thinking it’s spring already. So I dropped my backpack on the porch and headed around to the backyard, Sheba trotting next to me. At the split-rail fence that marked the edge of our property, I put my left foot on the well-worn groove on the bottom rail and swung my right leg over the top. Sheba scooted under the bottom rail, and we were in the woods. I wandered the old deer trails under the bare brown oaks and maples, their dried leaves crunching underfoot. I ended up at the small, spring-fed creek that, as it flowed through town and got bigger, became Black Creek. Down in town, the railroad tracks followed Black Creek a good ways, and the two of them formed the dividing line of the town: on the uphill side, the north side, were the more respectable (and all white) families. People who lived in nice houses and had flower gardens.

On the south side of the creek, folks lived in trailers or crummy little houses with rusty cars and weeds in their yards.

Up here at the headwaters, though, it was just a little stream, not even big enough to swim in or float on. Mostly it was a watering hole for wild animals. I’d spotted deer, wild turkeys, foxes, raccoons, and once, a young black bear drinking at the creek.

Downstream just a little ways there was a pool that’s fed by a small waterfall and partially dammed by an old ironwood log. It was just big enough for a couple of five-year-olds to go skinny-dipping in, if they didn’t know any better.

I hopped over the creek and followed another deer trail to Old Longlimb, a white oak and the largest tree I’d ever seen. I called it that after reading about an ancient tree in the Shire where the Hobbits would gather for picnics and stuff. Its dark, mossy trunk would take four people stretched arm to arm to circle it. Its twisty branches dropped low enough to grab onto, which I did, and hoisted myself up. Another branch was close enough to grab, so I did, pulling with my arms and pushing with my feet, branch after branch around the great trunk, till I found a comfortable spot. I settled into the crook of the branch; it was rough, but the perfect shape to sit in. The tree was so ancient and huge, I felt like I was on a sleeping giant. Below me, Sheba bit at a spot on her back, then went back to sniffing around the tree.

I was just sitting there, enjoying the sounds of the wind in the branches and the occasional bird, when I heard something out of place. It was a loud creak and then a bang, like a car door opening and closing. The clear, dry air carried sounds well, so it was hard to tell how close or far away it was. So I grabbed another limb and another—my arms were starting to get tired—until I got high enough to where I could see the source of the sound.

In the distance, not too far, I could see Michael’s old house. It was strange seeing it now, after so long. His family had moved away about seven years ago—right after the “incident” at the creek—and the house had stood empty ever since. Michael’s Mama’s crepe myrtles had gone all leggy and rough, weeds choked the irises and daylilies in the flowerbeds along the front of the house, and the shed out back sagged from neglect. But now there was a brown station wagon parked in the driveway. I scooted farther out on the limb to get a better view.

An extremely tall, extremely blond man was standing at the back of the station wagon. He pulled out two big boxes stacked one on top of the other. It was too far to make out for sure, but both boxes had big yellow ovals with red letters, and what looked like a fish on the left side —the Bass Pro Shop logo. He took them over to the shed and balanced them on one arm while he unlocked the doors, looking all around before he did. He took the boxes inside and I could hear, faintly, the sounds of a hammer pounding, a power drill, chains rattling.

I thought about going over and introducing myself. After all, we were sort of neighbors. But something held me back, some funny feeling deep inside. And besides, I kind of liked being able to see him without him seeing me. Like a sniper. I watched him step out of the shed and hook the padlock on the doors, pulling it a couple times to make sure it locked. Then he looked around before heading inside the house.

So I dropped down out of Old Longlimb then, branch by branch, until my feet were on the ground again. I headed back to the house, Sheba by my side, hoping Daddy was home from work.

CHAPTER 3

THAT WEEKEND, THERE WAS ANOTHER explosion, this one much closer. It was a Sunday morning, gloriously late. I was in my room, lying in bed and listening to the weekly top forty with Casey Kasem, enjoying the fact that I didn’t have to rush and get ready for school. From where I was, I could see the sky out my window. It was late-winter bright and pale, and it occurred to me that today was Groundhog Day. A red-tailed hawk swooped by lazily. A gust of wind shook the mimosa tree outside my window, and its thin, bare branches swayed like a dancer’s hair.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!