Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tilted Axis Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

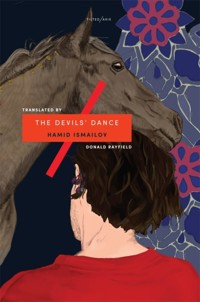

Winner of the EBRD Literature Prize 2019 On New Years' Eve 1938, the writer Abdulla Qodiriy is taken from his home by the Soviet secret police and thrown into a Tashkent prison. There, to distract himself from the physical and psychological torment of beatings and mindless interrogations, he attempts to mentally reconstruct the novel he was writing at the time of his arrest – based on the tragic life of the Uzbek poet-queen Oyhon, married to three khans in succession, and living as Abdulla now does, with the threat of execution hanging over her. As he gets to know his cellmates, Abdulla discovers that the Great Game of Oyhon's time, when English and Russian spies infiltrated the courts of Central Asia, has echoes in the 1930s present, but as his identification with his protagonist increases and past and present overlap it seems that Abdulla's inability to tell fact from fiction will be his undoing. The Devils' Dance brings to life the extraordinary culture of 19th century Turkestan, a world of lavish poetry recitals, brutal polo matches, and a cosmopolitan and culturally diverse Islam rarely described in western literature. Hamid Ismailov's virtuosic prose recreates this multilingual milieu in a digressive, intricately structured novel, dense with allusion, studded with quotes and sayings, and threaded through with modern and classical poetry. With this poignant, loving resurrection of both a culture and a literary canon brutally suppressed by a dictatorship which continues today, Ismailov demonstrates yet again his masterful marriage of contemporary international fiction and the Central Asian literary traditions, and his deserved position in the pantheon of both.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 589

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Devils’ Dance

Chapter 1

Polo

Autumn was particularly fine that year.

Wherever you happened to be – walking home down the empty streets from the new tram stop, casting an eye over the clay walls of Tashkent’s Samarkand Darvoza district, or going out into your own garden after a long day – every imaginable colour was visible under a bright blue sky. In autumns like this, the yellow and red leaves linger on the branches of trees and shrubs, as if they mean to remain there right until winter, quivering and shining in the pure, translucent air. But this motionless air and the tired sun’s cooling rays already hint at grief and melancholy. Could this bitterness emanate from the smoke of dry leaves, burning some distance away? Perhaps.

Abdulla had planned to prune his vines that day and prepare them for the winter. He had already cut and dried a stack of reeds to wrap round the vines; his children, playing with fire, had nearly burnt the stack down. But for the grace of God, there would have been a disaster. Walking about with his secateurs, Abdulla noticed that some of the ties holding the vines to the stakes were torn, leaving the vines limp. He couldn’t work out how this had happened: had the harvest been too plentiful, or had the plants not been cared for properly? Probably the latter: this summer and early autumn, he hadn’t managed to give them the attention they needed, and the vines had had a bad time of it. He was uneasy. He had the impression that some devilish tricks had been at play ever since he freed the vines from their wrappings in early spring. Almost daily, you could hear bands playing loud music, and endless cheering in the streets. Enormous portraits hung everywhere from the building on Xadra Square as far as Urda. Every pole stuck into the earth had a bright red banner on its end. As for the nights, his friends were being snatched away: it was like a field being weeded.

Not long ago, the mullah’s son G’ozi Yunus turned up – dishevelled and unwashed from constantly having to run and hide – and asked Abdulla to lend him some money, pledging his father’s gold watch as a token of his trustworthiness. Then Cho’lpon’s wife Katya came, distraught, bursting into tears and begging Abdulla to write a letter of support. ‘They’ll trust you,’ she said. But who would trust anyone these days? These were vicious, unpredictable times; clearly, they hadn’t finished weeding the field. As the great poet Navoi wrote, ‘Fire has broken out in the Mozandaron forests’. And in the conflagration everything is burnt, regardless of whether it is dry or wet. Well, if it were up to him, he would have been like a saddled horse, raring to go. Just say ‘Chuh’ and he’d be off.

With these gloomy thoughts in mind, Abdulla bent down to the ground to prune the thin, lower shoots of the vines. He systematically got rid of any crooked branches. If only his children would come running up in a noisy throng to help. Sadly, the eldest had fallen ill some time ago and was still in bed; otherwise he would have joined his father and the job would have been a pleasure. The youngest, Ma’sud, his father’s pampered favourite, might not know the difference between a rake and a bill-hook, but he was an amusing chatterbox. The thought made Abdulla smile. The toddler found everything fun: if you put a ladder against a vine stake he would clamber to the top like a monkey, chattering, ‘Dad, Dad, let me prune the top of the vine…’ ‘Of course you can!’ Abdulla would say.

Possibly, Abdulla wouldn’t have time to prune, tie back and cover all the vines with reeds today. But there was always tomorrow and, if God was willing, the day after that. Soon after he’d protected his vines, the cold weather would pass, the spring rains would bring forth new shoots from the earth, and the cuttings he had planted in winter would come into bud. It was always like that: first you pack and wrap each vine for the winter; the next thing you know, everything unfurls in the sun and in no time at all it’s green again. Just like literature, Abdulla thought, as he wiped a drop of sweat from the bridge of his nose.

The flashes of sunlight coming through the leaves must have dazzled him, for it was only now, when he tugged at a vine shoot bearing an enormous, palm-shaped leaf, that he discovered a small bunch of grapes underneath it: the qirmizka which he’d managed to get hold of and plant last year with great difficulty. The little bunch of fruit hiding under a gigantic leaf had ripened fully and, true to its name, produced round, bright-red berries, as tiny as dewdrops, so that they looked more like a pretty toy than fruit. Abdulla’s heart pounded with excitement. He had been nurturing an idea for a book: the story of a beautiful slave-girl who became the wife of three khans. The autumn discovery of a bunch of berries as red as the maiden’s blushing cheek, hidden among the vine’s bare branches, had brought on a sudden clarity and harmony. Turning towards the house, he called out joyfully, ‘Ma’sud, child, come here quick!’ But suppose the first fruit is too bitter? He plucked a berry from the bunch that he meant to give the toddler, and put it in his own mouth. Ramadan had just ended: he had forgotten the feel of food in daylight. The large pip crunched between Abdulla’s teeth, and its sweet flesh dissolved like honey through his entire body.

And suddenly he had a revelation: he knew how to begin his book. It would be a terrific story, surpassing both Past Daysand The Scorpion from the Altar. Ahmad Qori, who lived at the top of Abdulla’s street, had lent him a stack of books by the classic historians, and he had already researched the fine details. If he could get the supplies in quickly he could then be on his own, sitting in front of the warm coal fire of his sandal. Surely the three months of cold would be long enough for him to finish his novel.

Abdulla didn’t wait for his youngest child to toddle out from the ancestral house: he picked one more berry of the unexpected gift, tucked the tiny bunch of grapes behind his ear and got down to work.

On 31 December, 1937, a freezing winter’s day, Abdulla was taken from his home and put in prison, neither charged nor tried. So he did not begin his narrative with that early-ripening bunch of grapes in the shade of a broad leaf. Instead, Abdulla began his novel by describing a typical game of bozkashi, where players fight for a goat carcass…

—

Nasrullo-xon, ruler of Qarshi, was very fond of bozkashi, though as a spectator rather than a participant. Today, mounted on a bay racehorse which had only just been brought out from the stables, he rode onto the boundless meadow that lay outside the city. He preferred bay horses to those of any other colour, possibly because he could whip the horse’s croup or slash its leg with his sword and the blood would barely be noticeable against its copper coat. When they saw their ruler and his courtiers, the people raised their voices in welcome. Nasrullo glanced at his lively mount with satisfaction: tiny golden bells were attached to its mane, and it quivered nervously each time it caught the faint sound of their ringing. The soft leather bridle was decorated with mother-of-pearl, the saddle edged in red gold, while the saddle-cloth was made of white baby camel wool felt. ‘Damn you,’ the corpulent ruler barked at his horse every time he was jolted. And what a wonderful gold-embroidered gown he wore! It shone so bright that it dazzled the eyes. But even more bewitching was his belt with its pure gold buckle and a jewel the size of a horse’s eye. A scabbard and sword were attached by a strap to the belt. Nobody would doubt that the khan’s horse alone was worth more than all the possessions of the crowd that had gathered here. Ah, what a treasure, Nasrullo thought, bursting with pride as he gave his horse a slap on the croup.

As he rode up to a spacious open marquee, one of his eager guards immediately seized the reins of his horse and deftly hobbled it, while two servant boys worked the fans on either side: the applause was immediately replaced by silence. The khan’s chef and the city mufti stepped out. The mufti made a long speech in praise of the holy city of Bukhara and the dynasty of the Mangits who had brought Islam to their world, and also in praise of this dynasty’s precious jewel, Prince Nasrullo. He stepped aside only when the ruler waved his riding whip, after which the court chef came forward. Today he spoke as the master of the games: he shouted out orders to the riders while their horses stamped their hooves and snorted. ‘Firstly,’ the chef roared, ‘don’t pull each other off your horses, and don’t hit each other with your whips. Secondly,’ his throat straining a little with the effort, ‘don’t let your horses bite or kick. Thirdly, don’t let anyone who falls off his horse be trampled.’ ‘Quite right! Quite right!’ the people shouted in approval, punctuating these announcements. Just then, two horsemen came rushing up on black steeds, clutching to their thighs the carcass of a goat, the size of a calf. The horsemen pulled up about ten yards from the ruler’s marquee, just long enough to let the carcass thud to the ground. Then they wheeled around and galloped off, shoulder to shoulder, towards the crowd.

‘The goat’s been lifted!’ the master of the games cried out, disappearing all of a sudden behind the cloud of dust left behind by the riders rushing into the fray. It was like the Last Judgement: the wild horses barely controlled by their riders; the sound of hooves hitting the ground, of riders urging their mounts on, and of the spectators roaring; it was as if tight reins had been loosened, everything had leapt into motion and been drowned in noise. In the distance a flock of crows, tempted by the carcass, soared into the air.

‘Grab it,’ one man yelled. ‘Hold it,’ another said. The thousands who had assembled to watch echoed such cries. There was such confusion that it was hard to work out what was happening. A dog wouldn’t have been able to recognise its own master.

The snorting of the horses as they joined battle either frightened or excited Nasrullo’s bay – it too tried to rush forwards, despite its fetters. It managed to keep its balance, but lashed out furiously with its hind hooves. The Prince gripped the reins hard to hold the horse back, and two guards clung to the stirrups on either side. The horse twisted its head and foam spattered from its mouth while Nasrullo’s whip rained down blows. How could the ruler see the game like this?

All he could make out was brief glimpses of necks colliding against necks. His heart was pounding. He wanted to push his guards aside and ride into the thick of the game, using his sword to clear a path if necessary, then bend down and pick up the dead goat, his whip poised between his teeth… As if it had guessed what its master was thinking, the bay horse rushed forward again. If a piercing, heart-stopping cry had not just then come from the crush of circling horses, then who knows? Perhaps Nasrullo would have overlooked his royal status and thrown himself into the skirmish.

The flanks of the horses on the outer edge shifted and he caught a glimpse between their hooves of a carcass, not a goat’s but a man’s, being picked up by the ankle and flung onto the back of a horse.

‘He’s been trampled, trampled!’ the people clamoured, and the court chamberlain hurried over to the scrum, which stopped moving. Then a rider burst forth from the mass of horse flesh: the body of his fellow contestant hung lifelessly from his horse’s back. The riderless horse, a young dun not much more than a colt, followed: its reins were grabbed and passed along until they reached the chamberlain, who bowed and looked enquiringly at the Prince. Nasrullo nodded. Two servants brought a brocade gown from the marquee and threw it over the dun horse’s back. The chamberlain handed the reins to the rider who had brought the contestant’s body out of the crush, and the man trotted off, leading both horses towards the lamenting spectators.

Despite the hysterical tears of the dead man’s relatives, the game resumed, the goat’s carcass thrown back to be torn apart. This time the horsemen who had been waiting at the edge of the meadow galloped to the centre.

A week earlier, Haydar, Emir of Bukhara and Nasrullo’s father, had visited Qarshi. Today the Emir’s vizier, Chief Minister Hakim, had sent a courier with the following message, ‘Your father and noble benefactor fell ill on his return: despite the doctor’s efforts, His Majesty’s condition worsens with each day.’ The Chief Minister also added an oral message: ‘Make your preparations.’

Nasrullo’s father was devoted to intellectual pursuits, and the Mangit dynasty had weakened with him; the Emirate was swamped with intrigues and betrayal spread like a contagion. Recently, a group of armed men from the Chinese-Kipchak district had raided the viceroy of Samarkand and Umar, Emir of Kokand, had taken advantage of the situation by besieging Jizzax castle.

Meanwhile Nasrullo’s father’s condition was worsening. Could that plotting chef have put something in the food during his visit to his Majesty? He had been boasting that he had a stock of arsenic which could kill a horse with a single drop. Could he have snuck it into some dish of plov? The man would have to be interrogated… But never mind that now. First, Nasrullo had his duties to carry out.

There was more whooping from the riders, then uproar and a deafening cry. ‘The goat, the goat’s been lifted!’ As the goat was held up, one man tried to grab it, only to have his arm violently knocked away by another rider’s knee. There was a general clamour while the second rider snatched the carcass and galloped away at great speed. This rider was very young, his horse the same bay colour as the prince’s. He was pursued by other horses of every conceivable colour and breed: chestnuts, blacks, greys and browns, whites and piebalds, Akhal-Teke and Karabair, duns and light bays. There was no chance of the chamberlain’s orders – ‘Don’t hit, kick, bite or unhorse!’ – being observed now. Men lashed out with their whips wherever they could, at faces or heads; horses harrumphed as they knocked each other over; fallen riders, trampled by hooves, lay on the turf.

The bay horse had barely made fifty yards when it stumbled and came to a sudden halt. Immediately, two other riders came galloping up on both sides and the battle broke out again. At full tilt, the bay horse’s rider hit one of his competitors in the side with the handle of his whip, then veered off to the left. He directed his knee at the hand of the second – who had just managed to clutch the goat – and threw him from his saddle, dragging his victim a few yards.

‘What a rider!’ Nasrullo exclaimed. He couldn’t help comparing himself with this youth who had not only managed to snatch the goat from someone else’s firm grip, but to carry it off, too, out of the scrum. If his father, the sovereign, had been present now, Nasrullo would certainly have summoned the master of the games to his presence and reprimanded him for allowing the rules to be breached; but now, in thrall to his own private thoughts, he merely expressed his admiration for the horseman. If anything happened to his father, then Nasrullo’s brothers, the eldest Husein, the younger Umar, Zabair, Hamza and Sardar, would each try to take the throne, just as these horsemen had scuffled over the goat carcass. But that prize would not go to anyone like these dolts on their clumsy nags; it would of course be him, Emir Nasrullo, dominating all on his lively bay steed.

Not sparing even a glance for his bewildered courtiers, the ruler left just when the game was at its nail-biting peak and – his horse no longer hobbled – he rode off towards the palace.

—

It was significant that Abdulla’s novel began not with the miraculous discovery of the bunch of grapes, but with the game of bozkashi over the carcass of a goat.

On 31 December, they had broken into his house, ignoring the shrieks and cries of his children and wife who had gathered round the dinner-table for the New Year’s feast. The NKVD men overturned the dinner table and stormed through the house, ransacking everything, rummaging through Abdulla’s books and papers: just then, the spectacle of that game of bozkashi passed through Abdulla’s mind. Just as I was imagining myself to be a horse ready and saddled, waiting to be told ‘Chuh’, these ‘riders’ seem to be grabbing me as they would a goat’s carcass, Abdulla was thinking, when the men handcuffed him, dragged him out into the yard and bundled him into the sleek car parked by his gates, as his weeping household looked on.

While crossing Xadra square, Abdulla heard the explosions of fireworks, and fragments of a celebratory speech booming from a loudspeaker. What a pity: the New Year presents which he’d brought back after a cultural evening at the Railway Workers’ Palace were tucked away at home. There were packets of confectionery from Moscow and oranges, the colour of the setting sun, fruit for each child. Would his wife, Rahbar, hand them out once the children had calmed down, or would she be too upset to remember?

Abdulla had been arrested once before, eleven years ago, so he was not particularly bewildered or aghast on this occasion. Then, his soul had rebelled against the injustice; now he felt nothing much. His only regret was that his children were being deprived of the joys of New Year’s, and that the work he had planned for the winter had been interrupted.

He could hear the festive clamour of trumpets, chalumeaux, drums: each time the car bumped over a pothole, his handcuffs rattled, turning his mind to quite a different occasion, a scene from the novel his handcuffed hands should have been writing…

Early one morning at the end of summer, in the year 1235 by the Muslim calendar, a burst of shawms rent the air of the city of Kokand. Town criers loudly proclaimed to citizens and to visitors that the Muslim Emir Umar was to wed the daughter of the revered G’ozi-xo’ja. Doleful music and Hafiz songs could be heard coming from the palace. Plov was dished out for the people in the square, while the palace’s guests and courtiers were to be entertained to a banquet lasting three continuous days.

This was not the Emir’s first marriage feast: on this occasion the Emir and his people were beginning a three-day celebration, instead of the customary longer celebrations. Florists were staggering to the palace with armfuls of flowers; the confectioners stood over their cauldrons, conjuring up halva, sheep-lard pastries, boiled sweets and candy on sticks; two Russian soldiers, prisoners of war, removed the covers from the cannon barrels, which they cleaned with wooden brass-tipped rods in preparation for a spectacular salvo.

Meanwhile the Emir, for whom entire towns and fortresses were not plunder enough, sat enchanted with the prospect of yet another conquest: an eighteen-year-old beauty, whose equal could not be found in eighteen thousand worlds, and who that night was to become his third wife! As the revered poet Navoi said:

Eighteen thousand worlds yet never once seen:This girl, slim as a cypress, and barely eighteen.Alas, a number of intrigues were put into place for the Emir to get her. A new stanza was composed:

Oh angel nymph, grief has weakened my soul:The sword of exile has drained my blood whole.While Umar was in Shahrixon to see his younger sister Oftob, he also encountered the clever and virtuous wife of the Khan of Shahrixon, who offhandedly told the Emir: ‘Sire, you may remember being angry with G’ozi-xo’ja and expelling him from his home. This man now lives in a cottage very close by, just behind my house, and he is very poor. But he has a daughter called Oyxon, a girl of indescribable beauty – words simply can’t capture her, tongues become numb, pens break. As the couplet says:

The moment I see her, my eyes run with tearsAs the stars only shine when the sun disappears.This wise woman described the girl so vividly that the Emir suspected it could not be true. When the other guests had left, he questioned Oftob, and the cunning princess replied, ‘My lord, I have been lucky enough to see this girl: her face is as smooth as porcelain, her eyes are like two evening stars when night falls, her waist is as small as a wasp’s, her buttocks are as heavy as rounded sacks of sand…’ Oftob resorted to the language of A Thousand and One Nights, which she and the Emir had so loved to listen to when they were children: Umar’s heart was conquered.

Several times he sent matchmakers to G’ozi-xo’ja’s house, but the reply was always ‘no’. The pretext was that Oyxon was betrothed to a relative, that their marriage was imminent, after which G’ozi-xo’ja gave a detailed account of his poverty and complained that he was being unjustly punished and that Umar’s actions contradicted the laws of Islam; but, if his Lordship wished to force a marriage, then that was in his power and on his conscience. G’ozi-xo’ja added that his wife hadn’t stopped weeping since the matchmakers started pestering their household. Then he sent the matchmakers away. And yet…

—

It was dark when the car came to a sudden halt and Abdulla lost the thread of his thoughts. They must have arrived at the prison. What had he been thinking about? Oh yes, the five bright-red oranges he hadn’t been able to give his children, now left in a house where the lights were out. When he was still very young, he’d written a story called ‘Devils’ Dance’ about something terrible that had happened to his father. Could Abdulla have been taken captive by devils, as his father was?

The doors of the vehicle were wrenched open. The snow fell quietly, but in big flakes: a shout rang through this lacework: ‘Qodiriy, out!’ The courtyard was a shade of white tinged with blue, a pure covering still untouched by human feet and surrounded on all four sides by dark brown buildings.

—

Hands cuffed, elbows gripped, Abdulla was taken down a dark staircase into the building’s basement. In one of the niches, by the dim light of the caged paraffin lamp, a swarthy Russian stuck his hands under Abdulla’s gown and poked in all his pockets, pulling out everything to the last penny, and then, after feeling his trousers, removed his thick leather belt. ‘Sign this!’ he barked, holding out a piece of paper. Abdulla gestured to his handcuffed wrists. ‘Well, scribbler,’ the guard laughed, ‘you’ve had your itchy little hands put out of action!’ He kicked Abdulla in the knee so hard that the latter curled up in agony. ‘Hold the pen with your teeth,’ the Russian demanded.

‘Hold on, Vinokurov,’ said one of the men who had searched Abdulla’s house. ‘Watch you don’t finish him straight away, we’ve only just brought him in! I’ve still got to interrogate the son of a bitch.’ This man, evidently in charge, wished Vinokurov a Happy New Year before he left, presumably to celebrate with his own family.

Whether out of annoyance at having to work on New Year’s eve, or because he’d started the festive drinking early, Vinokurov kicked, cursed and beat Abdulla before throwing him into the solitary cell. Abdulla wanted to strangle his tormenter, but his hands were shackled and he hadn’t the courage to use his teeth. He could only bite his lips till they bled.

You get used to physical pain: you synchronise your breathing to its throbbing waves, you are ready for the waves to surge up and you can wait for the waves to die down. But the pains of humiliation are unbearable, and it is impossible to endure the suffering caused by your own helplessness. At first Abdulla attributed Vinokurov’s brutality to the fact that he was a Russian, but he then recalled that among the men who searched his house there had been an interrogator who spoke Uzbek like a Tatar, replacing all his ‘j’s with ‘y’s.

In prison you can’t avoid getting a kicking. In 1926, too, Abdulla had been beaten within an inch of his life. What made his blood boil was not the physical pain so much as the treachery of his own people, black-eyed blood relatives whom he had trusted and considered to be friends. Back then he’d begged for death’s release: that would have been easier to bear than the company of his own black-eyed friends. He’d been too young then: he hadn’t thought of his children, nor of Rahbar.

Had Rahbar given the children the oranges he’d meant for them? Tomorrow (but wasn’t it tomorrow already?) Abdulla had planned to take them to see the New Year fir at the Railway Workers’ Palace, where the biggest and best celebrations were supposed to take place. Last year the children’s favourites had been the trained dogs which answered questions and took turns pulling each other round on sleighs. Would Rahbar take them this time, and would they be allowed in if she did? Might they find themselves turned away at the doors, as the family of an arrested man? His heart sank at the thought.

Abdulla recalled a day from his own childhood, when he had dressed up in new trousers and an Uzbek gown to go to the Christmas tree celebrations. The caretaker at his Russian-language school stopped him at the school gates. ‘Have you become a kaffir now?’ the man grumbled, raising his stick to deal Abdulla a terrific blow on the thigh. The literature teacher, seeing this, hurried over and rebuked him: ‘This is a celebration of the birth of Jesus son of Mary, and Jesus is a prophet of yours!’ Abdulla’s leg was bleeding and his new trousers were stained; he ended up visiting the hospital instead of the Christmas tree. The teacher drove him all the way home, in his own carriage: a Russian, who had defended him from an Uzbek. No, generosity or meanness had nothing to do with nationality.

After all, now the whole country was run by a Georgian, and the result? Everyone was eating each other’s flesh.

—

Less than a week after the bozkashi game, another message came from Chief Minister Hakim in Bukhara to Nasrullo in Qarshi. ‘Your father, our benefactor, has ended his journey on earth and set off for the true world. We keep the fortress’s high gates locked, and we have not yet announced this news to anyone else. Take this opportunity: bring your troops at a gallop to holy Bukhara and occupy the place that befits you.’ Since all the preparations for this outcome had been made, Nasrullo set off for Bukhara that same day with three hundred warriors.

But the cat had to be let out of the bag. The news of the grief that had overcome Emir Haydar’s harem spread like wildfire through the Bukhara markets and then the whole city. When the Emir’s eldest son Husayn heard the news, he too gathered his troops and dashed off to the fortress.

Chief Minister Hakim kept the gates shut, as he had promised Nasrullo. Nasrullo moved with his elite troops towards Bukhara, but Husayn fired on the rebel army with artillery and rifles. They got as far as the fortress walls, and Husayn fought them at the mint next to the fortress, where they had taken cover.

Then Chief Minister Hakim ordered rocks and beams to be hurled down from the fortress walls onto Husayn’s troops. One of these missiles struck Husayn’s head: he was bleeding badly, but would not retreat. Instead, his men – enraged at the sight of their injured prince – climbed over the barriers and rushed to the fortress gates, smashing them down with the same rocks that had been hurled at them.

As a drop becomes a rivulet, and a rivulet a river, and a river a torrent, so the men broke into the fortress in a matter of hours, pouring in until they had flooded it. The wounded prince Husayn rode through the open gates as the new Emir. Despite extensive searches, the rebellious vizier Hakim was nowhere to be found. Shortly afterwards he appeared before the Emir of his own accord, carrying the severed head of his chief of artillery. ‘Forgive your servant: I was in the grip of ignorance, when this ungrateful dog started firing cannon instead of opening the gates to Your Majesty,’ he said, bowing and scraping at length. Husayn forgave him his sins, appointing Hakim as his vizier as his father had done before him.

The next day Husayn was crowned Emir, but he did not hold power for long; a mysterious illness forced him off the throne in less than three months. The doctors failed to conjure one of their miracles, and Emir Husayn left this world of sorrows. When Nasrullo heard what had happened, his thoughts turned to his master chef, who he had only recently sent to serve his brother Husayn as a peace-offering: ‘Seems the bastard took his arsenic with him’. Then he gathered his army and set off for Bukhara once again.

—

Thoughts have strange paths. Where had all this come from? The injuries to his body, Vinokurov’s threats, the immortal Georgian Leader? After all, Abdulla had been thinking only about his children, left to weep on New Year’s eve.

His father was right when he said that a man can be in thrall to devils, especially if he is a writer. You have only to set to work to be gripped by your plans and inventions, and everything else seems vanity, triviality, a distraction. Over the last month Abdulla had covered reams of paper, having told himself: If I can sit down on my own this winter, I will finish writing the novel. And now all those hopes had been dashed. The Tatar NKVD man had found the manuscript, stuffed it in the only suitcase in the house, and taken it away with him. And he was hardly going to read it, was he? Could he even decipher the old Arabic script of Uzbek? Or would he hire some black-eyed locals to read it for him?

Why hadn’t Abdulla begun his story with a description of the bunch of grapes? He might have got away with saying that this was just a little sketch of a fictitious gardener. But now his pieces would certainly damn him. Thoughts have strange paths, indeed.

He had only recently been thinking about Umar’s first marriage in 1220 to Nodira, daughter of the governor of Andijan. Abdulla had carefully worked out all the details of the matchmaking, the wedding ceremony obligatory for any marriage in the East. So why had his thoughts switched from one marriage to the other? Why does it happen that you get carried away writing about something and suddenly a single word or sentence makes you deviate from your original idea?

Take now, for instance: is Abdulla trying to lull his sense of pain and humiliation? Or are the habits of many years taking over so that even here, lying in this God-forsaken place, after letting his head fall on the pillow and saying his evening prayer, he lets his thoughts roam free of whatever was shackling them, free of anything that has nothing to do with the task in hand: writing? But he hadn’t yet pronounced the words of the prayer, ‘I lie down in peace’…

Abdulla had described every detail of Khan Umar’s first wedding: the ceremony in the state palace, the dancing and the games, the laughter and the joyful voices. The drumbeats that shook the sky’s blue dome when the people heard that the newly-weds had retired. The intoxicating joy which foamed in chalices while the sound of music filled hearts with delight and ecstasy.

That’s why he sought to describe the second marriage in a different key.

For a third time Umar sent a matchmaker to G’ozi-xo’ja’s house: this time it was the talkative Hakim, Umar’s sister’s son, a relation which made him a mahram, a man entitled to enter the harem. The Emir was wary of letting an outsider see his future bride’s beauty, but he could allow his nephew to behold her. Only the matchmakers and the girl’s father, whose white brows were wet with sweat, knew what was said during the negotiations. Realising that it was impossible to play with fire, G’ozi-xo’ja reluctantly nodded his agreement.

That same morning Hakim brought the girl home with him, entrusting her to the care of his mother Oftob. Delighted by the bride’s beauty, the young matchmaker recited a Persian couplet to his mother:

A miracle of beauty! On seeing her figure and movementEven a hundred-year old hermit will gird his belt!The poor girl arrived wearing an old dress: Emir Umar was in a hurry to marry, so he dressed her in silk and ordered the old gown be given to his concubines, since it was too sacred to be thrown away. The concubines spurned the offer…

But no sooner had Abdulla composed this scene than the idea flew away like a spark. What was going on?

Breaking the cell’s silence, bouncing off the walls and the bars, Vinokurov’s thunderous voice slurred the words: ‘Happy New Year, you pricks!’

For a moment, Abdulla didn’t know whether to laugh or to weep. Was there nobody left to keep that monster company, so that he had to remind people, if only the prisoners, that he still existed? Or had he got drunk with the soldiers on guard and was yelling this at them?

It was now New Year. Happy New Year to you, Abdulla! You said that if you could sit down for one winter, you would finish your novel. Clearly, you didn’t say inshallah at the time. But you had sensed the danger. Writers as well-known as you had already been arrested – Fitrat and Cho’lpon, G’ozi Yunus and Anqaboy – hadn’t they? Were you really likely to be left alone? When you tell a horse to ‘Chuh’, you have given it a bit more rope. He can go on writing for a bit, they would have thought, we’ll squash him when the time is ripe.

You’ll spend the new year wherever you spent New Year’s day, as the Russian proverb goes. So, Abdulla, it looks as if you’ll be spending this year in prison. Last time you were let out after six months, but now… Fitrat and Cho’lpon have been languishing here for longer than that time already, and who knows when they’ll be released? There might just be a few walls separating them from you, Abdulla. If you were to yell out like Vinokurov, might you get an answer?

Ah, he now remembered the spark that had just flashed in his head: Umar’s nephew Hakim waiting for the newly-weds, who were concealed behind a curtain on the first night of their wedding. Abdulla remembered Hakim’s book Selected Histories, almost by heart.

Because of his youth and naughtiness, your humble servant continued sitting by the curtain and, following the path of disrespect, raised a corner of the cover to hide under it so that he could enjoy the spectacle of the Sun meeting the Moon. The wine of desire foamed in the throat of Emir Umar-xon, and the moisture of shame appeared on the face of the beauty, like drops of dew on a rose. Moments of tenderness and elegant caresses were becoming more and more wild: the buyer’s desire grew, while the mistress of the goods gave ever greater concessions. For rain, ready to show the cloud’s final aim, was now about to pour down on the field of desire. The flower bud, submitting to the playful brazenness of the wind, was forced to unfurl its petals and turn itself bright red. And since the innate urge of the flower bud was to bear fruit, it opened fully under the force of the wind, so that a pearly drop now fell on its pollen.Would it have been at that precise moment that your humble servant was overcome by laughter? By whispering these words as if they were a prayer, Abdulla found that he could order his thoughts and see everything clearly. Hadn’t he just responded to Vinokurov’s roar with a burst of laughter? That was why he had recalled Hakim hiding behind a curtain. For a second, he felt as if he were Emir Umar’s nephew, except the curtain was now a stone wall and enclosed not a love scene but a death act. Wait, wait! This was no time to drop the reins. Watch out, don’t let a torrent of flighty thoughts sweep you away! If you ignored the superfluous florid style, the scene was described splendidly, especially the beginning and the end. Yet it seemed to have propelled Abdulla in an entirely different direction.

—

Oyxon was the eldest daughter of a revered hereditary sayid, G’ozi-xo’ja. She was not yet eighteen, but her many worries made her so serious that she was often mistaken for a younger sister of her mother Qantak. In the first days of the winter of 1232, their city O’ratepa was seized by Umar; all the sayids, including G’ozi-xo’ja, were arrested and shackled. Their property confiscated, they were driven out of their houses into the thick winter snow, crowded into wagons and packed off to Kokand. Oyxon was then fifteen. When they reached Kokand, cold and hungry, they found Umar still angry: he sent them even further, to Shahrixon. The family was so destitute that a flat loaf of bread seemed a gift from heaven, a set of old clothes a precious luxury. When they arrived at their place of exile, G’ozi-xo’ja’s family somehow built themselves a hovel to protect themselves from the fearful cold. They now had to live on what their father could earn by teaching children of the local poor to read and write, while Qandak and Oyxon made embroidered skull-caps. They embroidered in silk, but wore coarse calico dresses. All their earnings were spent on food. To relieve her father, Oyxon taught her younger siblings herself, putting them to bed at night, telling them fairy stories and writing verses for them.

The sufferings Qantak endured gave her a swollen goitre the following winter, and she developed a cough which she could not shake. G’ozi-xo’ja managed to get some deergrass to make an extract, which he gave her to drink. But nothing was of any use: by spring Qantak had departed this treacherous world, leaving behind five motherless children. There was a great deal of mourning and lamenting. The eldest daughter became her father’s sole support, a substitute mother to her siblings. Oyxon had been embroidering ten skull-caps a week; now she had to embroider twenty. Her doe-like eyes became as sharp as a blade and she herself as quick and nimble as a panther. She bathed, fed, nursed and taught the children, attending, also, to her prematurely aged father: her voice became as sweet as honey served in porcelain.

Her cousin Qosim was the first to notice the changes in her. He would come to Shahrixon to help his uncle’s family tend the vegetable plot. This time, with his uncle’s blessing, he put off going home, instead finding more jobs to do around the house: repairing shoes, patching up the mud-brick wall, setting up the bread-baking oven – there was no lack of things to do – any excuse to stay on.

G’ozi-xo’ja’s children grew fond of Qosim and lent a hand when he was working, or clung to his side and begged him to make them a clay toy. One of the girls – the youngest but one – insisted that she would be his wife when she grew up. Only Oyxon was reserved in her cousin’s presence, doing no more than what duty obliged of her: preparing tea, serving dinner, making up a spare bed on the floor.

At the beginning of spring, when everything else had been taken care of, Qosim stayed on to remove the winter covering from the vines and tie them to their stakes. He was so carried away by his task that he failed to accompany the elderly G’ozi-xo’ja, as he had intended, on his way to pay respects at the graves of the holy men in Eski-Novqat. At the time, Oyxon’s two younger sisters were staying with a neighbour to study more advanced reading and writing. The older boy was with his father; only the youngest, Nozim, was still at home. And, early in the morning, Nozim was still asleep.

Qosim fixed the loose cross-ties on the vine stakes and drove in new ones, before starting to rake over the dry reeds. He lifted the reeds carefully and saw that mercifully the frost hadn’t got at the vines: they could be tied to the stakes. The vine buds were already about to burst open: any day now the green shoots would break through.

‘Your good health, cousin!’ Oyxon greeted him, spreading a cloth on the ground and laying some flatbread on it. ‘Come and have some tea!’

‘As you wish,’ he replied. He moved to where she had laid out breakfast. Watching the girl get up to return to the house, her slender figure supple as a vine, he surprised himself by calling out, ‘I need your help!’

Oyxon looked around. ‘What for, cousin?’

She said the word ‘cousin’ so gently that Qosim couldn’t help missing a breath at the implications. He could barely whisper: ‘Would you mind holding the ladder? The crossbeams on the stakes are too thin, and I need to tie the vine branches firmly…’

Oyxon spun round to face him. ‘As you wish…’

The tea was left undrunk. His hands trembling with excitement, his breath quickening, Qosim picked up the ladder which lay near the vineyard and placed it against a strong supporting pillar. ‘If you hold it from this side, I’ll have the branches tied to the crossbeams in no time,’ he said.

Oyxon tensed her slim figure and gripped the ladder with all her strength. Imagining himself a tightrope walker, Qosim flew effortlessly up to the top. The spring breeze tickled his cheeks and hair; he felt he was flying not just over the vineyard, but the expanse of the whole world.

He used the reeds he had prepared to tie one branch and then another, but the third proved intractable, and had bent too far out. Qosim leaned out towards it, and while he swung out in one direction, the ladder went the other way: there was a high-pitched shriek and this time Qosim really did fly, only downwards, all the way to the ground.

‘Help!’ Oyxon cried as she rushed up to him and slapped his face, grabbing him by the collar and shaking him to see if there were any signs of life. A torrent of tears bathed Qosim’s face, but when her grieving lips touched his sweaty brow, a groan escaped the young man’s throat. Gripped by fear for what she had done, the girl cried out.

‘I saw it, I saw it, I saw the kiss,’ a small voice threatened her.

That night, putting Nozim to bed next to her, she stroked his head and whispered in a conspiratorial tone, ‘Don’t tell anyone what you saw this morning.’

Qosim was in bed in the next room. His entire body ached from the bruising, but his heart was intoxicated, like new green shoots in the wind.

At some point in the night, Abdulla raised himself up, dragged himself to a corner and slumped onto a black shape there. His body ached, but for some reason he felt at ease. How could that be?

—

Whether because Nozim had let slip the secret after all, or because G’ozi-xo’ja had spoken to his relatives in Eski-Novqat in the course of his brief pilgrimage, Qosim left for home as soon as he was able to. In the afternoon, G’ozi-xo’ja summoned his eldest daughter, intending to disclose his heart’s secret desire: to do so, he went back all the way to Adam and Eve, alluding to every Old Testament story there was.

‘Qosim is a good lad. He’s hard-working, good in the garden and the orchard, and he knows how to build things. Look at the extra space he built in our yard. He’s educated, too: his father has plans for him to study further in the Kokand madrasa. But I’m old now, my eyes don’t see as well as they used to, my hands have lost their strength, and I’ve lost my better half: there’s nobody to help run the household. If only your mother could have seen how you’ve grown up.’

Oyxon didn’t understand all this beating around the bush. At first she thought her father was rebuking her; she wept: ‘Father, forgive your unhappy daughter. It’s my fault, I’ve haven’t looked after you well. I’ve been too busy all the time, embroidering, or cooking, or laundering. I’ll give you more of my attention now. I can see I didn’t learn much from my mother…’

‘No, daughter, don’t talk like that: you’ve been both mother and father in this house, while I’ve been an old fool to express myself so badly. In the Qur’an, in the Surat Al-Hujur’at it says “O people! Verily, we have created you men and women, we have made you nations and tribes, so that you should know one another…” Marriage between a man and a woman is a directive of the Prophet: you’ve reached the marriageable age, so I have decided…’

Oyxon’s trembling lips didn’t dare form the response, ‘As you command!’ She merely nodded and bowed her head.

At the end of spring it was decided that Oyxon and her young brothers would stay for a week with their uncle in Eski-Novqat. Qosim came in his cart to fetch them. At dawn, after morning prayers and their father’s blessing, they set off. The cart had three thick rugs spread over a bed of reeds and hay. They jolted along a road, and towards noon they reached a Kyrgyz village. Here they broke for refreshment and, getting back into the cart after a bowl of real, icy Kyrgyz kumys both Oyxon’s brothers fell into a deep, sated sleep. The road passed through foothills, then mountains, following the course of a rushing stream. Sitting up front to drive the horses, Qosim broke the silence, speaking as if to himself:

‘How fresh the mountain breeze is!’ It could have been a question, or an exclamation by someone whose soul was brimming over with emotion.

Since the road they were travelling along was deserted, Oyxon removed her horse-hair veil, and, weary of the prolonged silence, responded: ‘Yes, the spring air is special, it’s different somehow…’

‘That’s what I felt when I was at the top of the ladder, standing over the vineyard.’ Qosim said quite without thinking, and immediately bit his tongue, for he could sense, even without turning round, that Oyxon’s heavy silence was one of embarrassment.

‘I was so clumsy,’ she apologised, ‘I couldn’t hold the ladder up…’

Qosim had the sense to change the subject: ‘Somehow, these mountains always make me want to sing.’

The bright greenery of the hills, the roar of the clear mountain torrent beneath them, the icy air and the aftereffect of the kumys combined to relax Oxyon’s guard: she nodded in agreement and added, overcome by reticence, ‘Perhaps you’ll sing something, cousin?’

Qosim didn’t wait to be asked twice. He filled his lungs, swelled his chest and began to sing:

Let the morning breeze hear my pleaLet the morning breeze hear my pleaHer eyes bright as Venus, her hair wild and freeThe grace of a cypress, brows black as can be!Let my prayers be heard by this shimmering beauty.She vanished from me like some mischievous fairyAnd left me to live with nothing but misery.We made to each other an unbreakable vowSo if one of us breaks it, it’s in God’s hands now.The young man’s voice rose higher and higher, as if competing with the winds that blew over the peaks. The high notes made his voice resonate, and the girl could not stop herself from quietly joining in.

They joined forces for a second song. Oyxon’s voice sounded less constrained in the open air. When Qosim sensed this change, he broke off and insisted jokingly, ‘Now let’s hear you, cousin Oyxon!’

She cast a glance at her brothers: seeing that they were still fast asleep, tipsy from the kumys, she sang verses which Qosim had never heard before.

If my voice starts to quaver, let strength come into itIf the flower is half-coloured, let blood fill it up.If tears overwhelm me, flowing night and dayAnd Venus burns my eye, let the sun rise with a sigh.The girl’s voice was as full of tenderness and shyness as the red poppies on the mountain slopes, as nimble and youthful as a vine, and as strong as the intoxicating sap of the earth. Apparently guessing what Qosim was thinking, Oyxon suddenly started singing sotto voce:

Though someone sets the ladder, don’t brush muck from the roof:Let the leaves drop in autumn, or let your gardener lend a hand.Every beat of his heart clearly confirmed to Qosim the authorship of this verse.

When you look at me, it means death in two worlds.If I come alive in one, I die in the other.Qosim nearly dropped the reins. Looking behind him, he saw that the evening sun, setting over the humped peaks, shone on the girl’s unveiled face, and that face seemed to him like a moon, shining desperately in the glare of the sun.

I tried to nail down today, and fix it foreverBut it rips my heart – let it go now in peace.Those words should have been sung by Qosim, not by her. The sun had half disappeared behind a mountain, leaving only a dim semi-circle behind. The girl seemed also to have waned, and she finished her song in a barely audible voice:

If my heart is full of holes, patched with repairs –Let the sky be like Oyxon, and the breeze fly the kite.The warmth of the sun and the song’s emotions kept the young people from feeling the chill now in the air, as they climbed onto the alpine pastures. Qosim recited the fourth prayer of the day crouching in a yurt, while a young Kyrgyz fed their horses. They took another young man along as a guide and set off again, so as to arrive before darkness fell. ‘There’s one small pass we still have to climb,’ said Qosim, translating for Oyxon and the children what his Kyrgyz friend had said. Oyxon found the pass terrifying. The road climbed very steeply, the horses fought for breath as they pulled the cart; Qosim and the young Kyrgyz dismounted, took the horses by the bridles and began pulling them up, while a third helper pushed the cart from behind.

As Oyxon had predicted in her song, the sun dropped behind the mountain and then seemed to freeze for a while. It couldn’t set fully, for their cart was climbing higher and higher, chasing the sun. Qosim pressed on as fast as he could, as if trying to hold back the sun, so that it would light up his cousin’s radiant face for longer, though that face was now concealed by the horse-hair veil. Wrapped in her black garments, Oyxon hunched fearfully. When they reached the top of the pass, the young man again felt the same soaring feeling that he had experienced in the vineyard. ‘Oh God, don’t let the cart collapse now as the ladder did then,’ he thought with a shudder, spitting for luck on his damp chest under his shirt. The mountain peak was still sunlit, but the first shadows of darkness had fallen over the lush valleys which flanked the pass.

Who knows what terrified Oyxon most, the descent from these mountains, or the start of the journey, but it was already getting dark when they reached a place where the numerous rivulets of a mountain torrent streamed everywhere like a young girl’s braids. It took only another hour to reach Eski-Novqat, where the magnificent night sky glimmered with stars.

Oyxon was never as happy as she was in the week she spent there.

But less than a month later her father’s humble house was pestered by Umar’s matchmakers, and by the end of summer Oyxon found herself the third wife in the Emir’s harem: caught in a palace, like a bird in a golden cage.

After filling his mind with these thoughts, Abdulla could not tell what he was groaning over: whether it was the pain of young Qosim’s fall – not just off the ladder, or the mountain pass, but from the star-spangled heavens – or Oyxon’s agonised heart, which was reflected in the eyes of Abdulla’s children, standing aghast in the snow as he was taken away. Where was he? What was going on in this world, in this endless darkness? Was there anything other than pain?

Dropping down behind the mountains, the sun suddenly fell away, like five sunset-coloured oranges, and Abdulla fell into an oblivious sleep.

—

In the morning the prison door scraped open. Opening his eyes to see the duty soldier, who had brought him a bowl of gruel and a mug of tea, it took Abdulla a few moments to recall where he was. The first time you wake up in a prison is unique. Abdulla could never forget it. At night, as you fall into a heavy, dreamless slumber, you feel you are in prison, but in the morning, when you wake up, your first thought is: might yesterday’s nightmare have been merely a dream? And then you realise that it was neither a dream nor a nightmare, and that you really are in prison. You realise that on the night of 31 December, three men really had burst into your house, called in the neighbours as witnesses, started searching the premises, handcuffed you while your Rahbar and your children, who ran out in the snow in their night clothes, wept. ‘Pick me up,’ said Ma’sud, who was used to being held. ‘Daddy!’ he called, stretching his hands out to his handcuffed father.

It was true: he had been beaten and kicked. Even raising himself up to a sitting position, Abdulla’s body ached so much that he stretched out again where he had lain. No, what next? He’d missed his morning prayers: he must gently get to his feet, shuffle over to the water bucket in the corner, wash his face, hands and feet, and recite – however late – the morning prayer. Fighting his pain, Abdulla got up, washed, then went back to bed where – not knowing which direction Mecca was – he prayed facing the wall. He couldn’t stomach the bowl of gruel, but took a sip of the bitter tea.

The tea sent his thoughts down another circuitous path.

It occurred to him that these walls might possibly be housing the scholar G’ozi Yunus, the teacher Fitrat, perhaps, even Cho’lpon, yes, perhaps. Hadn’t Cho’lpon written about a girl singing in a cart: who could portray Shahrixon and Eski-Novqat better than Cho’lpon, a native of the region? Abdulla longed to see him. There was an enormous amount to talk about, all stored up in his mind. How likely was it that their paths would cross here? Could he tell Cho’lpon about his wife’s troubles? The first day in prison is always peculiar. Abdulla’s mind was constantly alert, listening to every scrabbling sound on the other side of the door. But for a very long time nothing happened. This dullness made him return to his idle, pointless thoughts. Again, you remember things; again, your soul is ground down between the heavy millstones of the mind. And all that results are conjectures. Guesses turn to dust if you blow on them.

—

It was like a heavy stone. But wasn’t the first time Oyxon awoke in her golden cage a hundred times worse? The girl had been raped, yet in the morning she came out to greet everyone – bowing to her own father G’ozi-xo’ja, and smiling at the other women, the aunts and wives of the Emir, the Emir who had raped her and left her with cramps in her throat and stomach. Momentarily pierced by the idea of this pain, Abdulla forgot his own grievances and directed his thoughts to the name of Allah.

A certain amount of time passed before the cell door opened again and a soldier barked an order in Russian: ‘Prisoner Qodiriy! Out, with your hands behind your back!’ Abdulla was taken to another tiny room in the basement, where they thrust a board with a number on it into his hand and photographed him, first full-face, then in profile. In a neighbouring cell an elderly Jewish man shaved Abdulla’s head and chin with a razor. The barber was clearly forbidden to open his mouth in front of the soldier standing by, or perhaps he was a mute: he hissed and whispered the whole time, made wordless shushing and whooshing sounds, waving his arms to satisfy his craving for communication. Now and again he tapped Abdulla’s cheek; when it was shaved and free of foam, he tugged at his shirt collar, bent down to his ear and whispered again.

Abdulla was reminded of Oyxon affectionately fussing over Qosim, and again he almost laughed. No, he had to behave seriously while the razor was shaving his head, and now his face, under the soldier’s icy gaze. And he didn’t want his laughter to get the unfortunate barber into trouble: wasn’t the barber just another prisoner? Or did he do this job precisely so as to keep his freedom? Having your hair cut is usually relaxing, but to lose all the hair on your head and your face in one fell swoop is disagreeable. Abdulla’s upper lip was swollen. It was a good thing that he hadn’t been photographed in this state. Either because he was now hairless, or because he was looking at the Russian soldier, a narrative strand occurred to him, which he would use to full effect in the novel he had planned.

In the early nineteenth century, in the Polish province of Szawel, then part of the Russian empire, a son was born to the aristocratic Witkiewicz family. His father named him Jan, but his mother, who was a Francophile, called him Jean. The boy grew up to be clever and quick-witted. Apart from Polish, he had a fluent command of Russian, English, French and German. At the age of fourteen, when he was a pupil at the grammar school in Kroży, Jan Witkiewicz created a secret society called the Black Brotherhood, but was caught by the Russian gendarmerie while publicly distributing poems and leaflets attacking Russians and Russian autocracy. Despite his youth, the boy was deprived of all his property, his rights and his freedom, and sent into exile.