9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

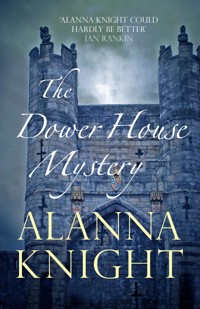

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Inspector Faro

- Sprache: Englisch

York, 1907. Newly retired Inspector Faro is delighted at the prospect of staying in the Dower House, situated on a Roman villa once home to Emperor Severus. But he arrives to find his wife Imogen distraught and desperately searching for her missing Irish cousin, who seems to have vanished without a trace . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 364

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Dower House Mystery

A Case for Inspector Faro

ALANNA KNIGHT

For Barbara Wood, with love and admiration

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Had they been on the lookout for portents, the year 1907 did not begin auspiciously for newly wedded, recently retired Chief Inspector Faro and his bride Imogen Crowe.

After visiting York, they would live in Edinburgh. Their Dublin flat presented problems regarding Imogen’s travels as a writer of historical biographies and the decision had been almost instant when a suitable Edinburgh house came up, with an accessible railway station to London and thence across to the Continent and beyond.

Aided and abetted in their search, they had been offered a permanent home with Rose, Jack and Meg Macmerry in Solomon’s Tower at the base of Arthur’s Seat. Large, ancient, romantic, its history lost in time, and almost ruinous in places, neither Faro nor Imogen were homemakers. Their thoughts did not linger on domesticity or the challenge offered by those vast empty rooms with their draughty stone walls, and they silently dreaded the possibility of a future living there, leaking pipes within, decaying stonework and foul weather without. They wanted a modern house, easy to maintain, where they could just settle down.

Even if Imogen’s lifestyle had included leisure enough to yearn for pretty curtains totally inadequate on those massive stone windows, Faro had no wish to try his hand at building a flight of bookshelves. So, as both had succumbed to streaming winter colds, Imogen spent each day searching the newspapers for appropriate houses, while Faro remained crouched over the cheery fire in the massive kitchen, the Tower’s only warm room despite the tapestries on the walls shuddering in the wind. He watched Imogen gallantly venturing outside, under shawls and umbrella, guiltily aware that his new role as husband sadly lacked the desirable and necessary ingredients of homemaking, such matters throughout his long working life having been the province and responsibility of Mrs Brook, his loyal and dependable housekeeper.

Grateful to Rose and Jack, who were relieved to see their marriage solemnised and made official at last after almost twenty years of living together, they were lured by the open aspects of the ever-expanding south side of Edinburgh, with sounds of the nearby railway line an added temptation.

The New Town constructed a century ago was solidly built with few open spaces and at a short distance from Solomon’s Tower. The one-time drove road down to the borders and thence to England now transported heavier traffic than horse-drawn carriages, and now renamed Dalkeith Road, sprouted a respectable vast terrace of six-storeyed houses.

The ever-expanding railway network had proved a great boon to the Faros, enabling them to visit places often difficult and almost inaccessible except by tortuous land and sea crossings taking several days. Until the turn of the century, Imogen Crowe had been classed as a non-desirable Irish woman with remote connections to the Irish Home Rule movement, before her free pardon from King Edward VII allowed her the right to settle in Britain and made living arrangements with Faro much easier.

While they were still hunting houses, by chance a suitable one came up. With Chief Inspector Jack Macmerry heavily involved in police work and Faro’s daughter Rose McQuinn absent on one of her lady investigator cases, Imogen and Faro had taken their daughter, nine-year-old Meg, to visit a school friend whose grandmother had a rather pretty house near Sheridan Place, Faro’s one-time home.

Imogen had been very impressed by the view from the house, with one large bay window looking across to Arthur’s Seat and another gazing down towards East Lothian and the coast. Facing south and west, it had the advantage of sunny days and warm rooms, not to be despised in Edinburgh’s somewhat chilly weather.

The owner, Mrs Mack, sighed. She was getting old, her legs bothered her and she didn’t need all those now unoccupied rooms up two flights of stairs, while downstairs − once the dining room and housekeeper’s domain of parlour and kitchen leading to the garden − was more than enough for her declining years.

She shook her head sadly, regarding Imogen with a gleam of hope. ‘It is all too much for me, with Sandy gone now. I never needed a housekeeper, but I just hate living alone. I’m a bit nervous these days and I just wish I could rent the upstairs to some reliable folk. But I don’t fancy having strangers living in the house.’ She paused and looked again at her little granddaughter’s escorts. The tall handsome man who, Janey whispered, was once a famous policeman. His wife, who seemed a lot younger, was lovely too, such a charming sympathetic manner. A nice, strong, respectable couple with good references.

She sighed and murmured, ‘Someone I could trust and who might even keep an eye on things if I was taken poorly.’ She patted her chest knowingly. ‘Not as fit as I once was. Getting old.’

The Faros exchanged a glance. The first floor with its magnificent views would be perfect, and what had been the maid’s room and the nursery on the top floor would provide extra space for the vast storage of all their books. It was an instant decision, the rent agreed and there was general jubilation from Mrs Mack, as well as the wee girls Janey and Meg, the latter in particular delighted at the prospect of her adored Imogen staying in Edinburgh. They had become great friends and the regard was mutual. Imogen had lots of time and hugs for Rose’s wee stepdaughter, who was Jack’s image.

A very excited Meg held both their hands skipping homeward along the one-time Coffin Lane. Once the end of the town and the last earthly sight of Edinburgh for condemned criminals, it had lost all sinister connotations and become just a pretty country road with hedgerows overflowing with colourful wildflowers.

Home up the hill to Samson’s Ribs and Solomon’s Tower, gasping to be first out with the news for Rose, Meg called: ‘Isn’t it wonderful, Ma? They’ll be living so near. Fancy Imo and Grandpa living just as far away as the Crowe flies, eh?’ she added, and they all laughed at the pun on Imogen’s name. ‘Isn’t that great!’

And so matters were speedily arranged, and as the upstairs rooms of No. 2 Preston Drove were fairly empty, what furniture remained was purchased from Mrs Mack, with additions provided from the Tower and local auction rooms.

Preparing to move in, Imogen had no doubts. She had a feeling about houses and the moment she had stepped across the threshold had known this was a good place. ‘My Celtic blood with its dash of Romany from my grandmother,’ she told Faro.

Imogen had loved their tiny flat in Dublin, easily accessible from Glasgow, as long as one was a good sailor across the notorious Irish Sea to Rossclare. Before the decision to settle in Edinburgh, it had been convenient as long as their travels across Europe permitted, and as long as Imogen produced books that retained their popularity. This always surprised her, expecting that each new one would somehow not reach the mark. But, so far, the source had not dried up, the stories still came and as long as Faro accompanied her she would continue writing. Research intrigued her even more than the writing, she often said, and Faro laughed:

‘You should have been a detective, like Rose, if that’s what you enjoy so much. After all it’s just searching for clues, isn’t it?’

They were content together now that Faro had retired. During their first years, meeting intermittently when he was between cases, Imogen was always fearful. Fearful for his safety, that the bullet or the knife would bring their life together to a cruel end. She wished that their age difference was less than twenty years, aware always that in the scheme of mortality she would outlive Faro, and she thought with anguish of those years alone.

Faro was well aware of their shadow too. He constantly wanted to put the ring on her finger, have her respectably married so that he could provide for the rest of her lifetime. Until last year, she had continuously refused, saying she did not need a certificate or a wedding ring or to repeat after the priest, ‘until death do us part’, followed by a nuptial Mass to bind her to the love of her life.

Faro forgot sometimes that she was still a Roman Catholic and occasionally when they were staying near a church she would take her rosary and disappear to Mass. In foreign cities, he was surprised. How did she understand it all?

She had laughed. ‘It is in Latin, of course. The same for all Christians.’

Except for Presbyterian Scots, in the religion he had been born and bred in Orkney, although his appearances in St Giles in Edinburgh were limited to occasions such as official police visits, weddings and funerals.

Daughter Rose had married an Irish Catholic, Sergeant Danny McQuinn, brought up by the nuns in an Edinburgh orphanage, but neither Rose nor her second husband Inspector Jack Macmerry were keen churchgoers, although Jack’s wee Meg was also being educated by the nuns in the convent at the Pleasance, chiefly because of its convenience as the nearest school to Solomon’s Tower.

When Faro had tried over the years to persuade Imogen into marriage, she had laughed. ‘You have a wife already, Faro. Sure now, it would be bigamy and you married to the Edinburgh City Police.’

And he realised then that she spoke the truth. The police, his dedication, had always been first in his life, even before his family. He had long ago known that he had neglected his first wife Lizzie, who had died in childbirth with their third child, a longed-for son. Rose and Emily had been shipped off to Orkney to live with his mother in Kirkwall and were rarely seen by their father, even on those dutiful summer holidays in Sheridan Place in Edinburgh − a father who was always too busy chasing criminals to spend an afternoon picnic with his two little daughters. He still carried guiltily the image of their upturned faces, their sad disappointed expressions, as Mrs Brook was allocated the task of deputising for this neglectful parent.

CHAPTER TWO

Faro had been both pleased and relieved by the prospect of remaining in Edinburgh. Much as he liked Dublin and the flat overlooking Phoenix Park, it could never become home. That was and could never be anywhere other than Edinburgh, although Yesnaby near Stromness in Orkney was close to his heart. This was home now to his mother, Mary Faro, who had moved in to look after his widowed daughter, Emily, and her little boy Magnus, although there was some question about who was doing the looking after. Neither Faro nor Imogen were sure, since Faro guessed that his mother − who had always kept her age a close secret − must be now well into her late eighties, although she showed few signs of slowing down.

But Orkney was too inaccessible for Imogen’s travels and Edinburgh was where he had spent most of his life from seventeen years old until his retirement from the City Police last year.

He had to admit relief at Imo’s delight in Preston Drove, slightly apprehensive that she might choose to return to Ireland and settle down back in Kerry at Carasheen, the family home of the vast clan of Crowes. He had been very wary in their pre-marriage days of their intense nosiness into his affairs and soon realised that although it was innocent enough and they meant no ill, the fact remained that privacy had not been invented for the Crowes: everyone who was allowed the privilege of stepping across their threshold brought with them their life as an open book to be scrutinised carefully, well read over and endlessly discussed in minute detail by all the family. Nothing was sacred, no secrets allowed, and what they didn’t know for sure, they would patiently dig for until they found out.

Imogen never knew her parents. Her father, Padraig Crowe, a talented artist with paintings in the Dublin Art Gallery, was lost in a sailing accident off the Blasket Islands when she was expected, and her heartbroken mother died from childbirth complications when Imogen was three weeks old. Passed round the family, she was eventually adopted by her infamous Uncle Phelan, an Ireland freedom fighter who hanged himself in an English jail after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Queen Victoria.

He had brought Imo to England with him and as a fifteen-year-old she had been locked in a prison cell awaiting trial, accused of conspiracy. A year later, with no evidence against her she had been released but forbidden to set foot in England again. Determined to become a writer, born with a gift that she cultivated through years of hardship, she finally achieved publication and worldwide acclaim. And so the years had gone by until a meeting in Cork with Bertie, then Prince of Wales. He had been captivated by this lovely clever Irish woman and one of the first things he did on ascending the throne as King Edward was to grant her a free pardon.

Now that the stage was set, so to speak, with a home for the foreseeable future, Faro and Imogen could make plans. Her forthcoming talk in York had been cancelled due to the untimely death of the society’s president and rescheduled for March 1907. As neither had ever been to York, they were looking forward to visiting the city built by the Romans and regarded as the most fascinating medieval city still intact in Britain, with its world-famous Minster.

Imogen had other plans too. The cold dead winter would soon be past, and they would be watching that annual reawakening of the world to another springtime. With Faro she had been consulting maps and had decided that, from York, with the now excellent railway, this presented a perfect chance of going over to the Continent from the port of Hull and in particular seeing Amsterdam.

She recalled being impressed on a brief visit, long before she met Jeremy Faro, by its new museum and always determined she would go back again.

She looked at their diary. Just weeks away, the wedding at Elrigg Castle on the Northumbria borders near Hadrian’s Wall, where she and Faro had met twenty years ago and loathed each other. She was godmother to the Elriggs’ only daughter, Mercia. It would be such a delight to go back with Faro as newly marrieds living, she hoped, happily ever after despite such a dire beginning. And a month later Amsterdam would be ablaze with tulips. Yes, she wrote dates in contentedly. Just another couple of weeks and February, never a good month, would be torn off the calendar for another year, with March and York in springtime to look forward to. Faro would love it, all that history and archaeology, museums and the rest.

But there was one more visit that must be included. Imogen produced her diary and pointed out that as the York event was still distant, either Faro or herself, but preferably both, must return to Dublin and release the flat. There were also several things happening that she was keen not to miss. Most important, a promise made to her friend Lady Gregory, whose new play The Rising of the Moon was to be premiered in Dublin’s Abbey Theatre in early March and their presence would be expected at the opening night. Isabella Gregory and Imogen Crowe, the same age and friends for many years, were both dedicated, as were Isabella’s plays, to the struggles for Irish freedom and a free state. A further bond was their passionate devotion to Women’s Suffrage.

The visit went ahead as planned, aware that at their meeting the day after the premiere of the play the talk would not only be of the splendid reviews but also of the outrage regarding an older story that had hit the headlines beyond England: on 13th February dedicated and fearless suffragettes had stormed Parliament where sixty of them were arrested and thrown into jail. However, Isabella had shyly welcomed Faro, glad that Imogen’s tall, handsome husband was not of dreaded English stock, but a Viking from Orkney (as Imogen always introduced him in Ireland). She tactfully refrained from adding to the introduction that he was or had been a chief inspector in the Edinburgh police.

The link with the Dublin flat severed, it remained to cross the Irish Sea to England and thence back to Edinburgh and their new home. Imogen was thankful on each crossing that both she and Faro were mercifully good sailors on often notoriously stormy voyages, while Faro, an avid reader of railway timetables, saw their decision to settle down and make Edinburgh their home with the widowed lady as an excellent choice. He was already looking forward to that cosy warm south- and west-facing house with the excellent views to coast, castle and Arthur’s Seat, having taken into account and making particular note of the accessibility just two miles’ distant of an excellent and frequent railway link with York.

However, the omens for their immediate travel were not good, in fact they were to be regarded with extreme caution. According to the philosophers of ancient Rome, mid-March, the date of the Faros intended first visit to York, was a significant and solemn threat not to be disregarded. Soothsayers of old would have warned him that since the murder of Emperor Julius Caesar in 44 BC, the ides of March was a cursed date and should be treated with caution by anyone setting foot in a city like York that owed its origins to and had been built by a Roman emperor.

For Faro and Imogen, the omens a soothsayer would have relished were all present, gathering patiently one by one on a horizon that, as twentieth-century persons basking in the wonders of a modern civilisation regarded as well beyond the dreams of ancient Rome, they were ready to ignore and amusedly dismiss as old superstitions …

At their peril.

CHAPTER THREE

Their sojourn in Edinburgh was a delight, but Imogen was doomed to go to York alone. Although the weeks were ticking away, the year, which had started badly, had some new hazards lying in wait in the form of a heavy snowstorm. On the eve of their departure for York, Faro was suffering from a lack of exercise and, regardless of the icy conditions, determined to climb that steep extinct volcano behind the Tower known to geographers and the world in general as Arthur’s Seat. It was an ill-advised decision: he slipped, fell and limped home assisted by Rose’s massive deerhound and family treasure, Thane. He had severely injured his right ankle. He had been shot in that leg during his service with the police, and it still troubled him. Now he was in great pain and could barely walk.

Rose decided a doctor’s attention was needed and Imogen agreed that he was in no condition to travel anywhere and he must abandon any thought of accompanying her to York.

So Imogen, who loved trains, went alone. She had held her breath as York approached and the sunny day with its cloudless sky suddenly revealed the Minster dominating the horizon, before the train, amid dramatic clouds of smoke, steamed to rest alongside a platform in the handsome railway station.

She had taken barely a dozen steps into the city, towards the hotel where she would stay and be welcomed by warm breezes touching the River Ouse with shafts of pearl, when she looked over the bridge and knew this was a place that had been waiting for her. If one could fall in love with a city, then Imogen Crowe was head over heels with York.

That evening her talk on writing historical biographies of women who had shaped history was received by an enthusiastic audience who asked the right kind of questions and ones to which she knew the right kind of answers.

The chairman, Theo Hardy, was one of the team of local archaeologists. His wife Belle had organised a dinner party at Dean Court Hotel in Imogen’s honour. The couple had been very impressed by Imogen’s talk and Belle insisted that they did not want the evening to end. They wanted to know more about Imogen Crowe and her fascinating life.

Belle raised her eyebrows and sighed in envy at the courage of this talented brave woman whose travels took her to so many places in Europe, and further afield to North Africa, into dangerous and almost inaccessible places for research. It was beyond her understanding that this author could, undaunted, face the hazards that lay in wait for a beautiful woman travelling alone.

‘Were you never afraid? I mean, of men?’ Belle added in a whisper as Theo went in search of their transport.

‘I soon knew how to deal with that situation, pick up enough of the language to make myself understood and so forth,’ Imogen said firmly. ‘A lesson I had to learn early on. And I also carried a gun.’

‘A gun!’ Belle shuddered. Travels among wild men always led to thoughts of rape. As for being armed with a gun, that was a very savage and unladylike addition to this picture of the lovely delicate-looking Imogen Crowe.

‘Theo and I often go to Egypt and Greece, and the way the labouring men look at me, I would be terrified on my own,’ said Belle.

At that moment, Theo returned. ‘Our car is waiting. We will accompany you.’ They insisted on driving her to the hotel, although she maintained that it was a short distance away and she would enjoy the evening air. York was so lovely.

They looked at each other. York had obviously enchanted Miss Crowe on her first visit. When was she leaving? Tomorrow? Oh, that was sad, she must come again very soon.

‘Yes,’ said Belle, clapping her hands and beaming at Imogen. ‘And please do bring your famous husband next time. Such a pity he couldn’t be with you tonight.’ A swift glance exchanged with Theo who added:

‘Of course, Inspector Faro. Everyone wants to meet him.’ He smiled. ‘I expect you know this already, but tales of his legendary career have spread far south of Scotland.’

That information always surprised Imogen as it did, in fact, Faro.

‘We have lots of room at the Dower House,’ said the eager ever-smiling Belle, ‘and we would be delighted if you could spare the time to honour us with a visit, wouldn’t we, Theo?’

Theo added enthusiastic agreement. Cards were exchanged. ‘Let us know when you are arriving and we will meet you,’ he said as the car stopped outside Imogen’s hotel.

Leaving such a nice friendly couple, Imogen considered their card again, and thought that perhaps this had been a very fortunate encounter. The Dower House was an imposing address, and although she would take the precaution of booking hotel accommodation for their next visit, she decided to keep the Hardys’ offer to herself until she had had a chance to inspect the premises and what might turn out to be a pleasant surprise for Faro, since he never enjoyed staying in a hotel, even a luxurious one, for an indefinite period. For anything more than a couple of nights necessitated by travelling, he missed the comfort and informality of home.

Before catching the Edinburgh train next day, with some difficulty and only by asking directions, she found the Irongate and had a look at the exterior of the Dower House. It was certainly large and imposing, even seen through the rain and a large umbrella that forbade a closer examination.

The weather was too depressing to explore York as she had hoped, and it remained to send ‘thank you’ flowers to Belle Hardy and scribble a special note for their kind offer.

The rain eased to a fine drizzle and on the lookout for a flower shop she walked down the Stonegate and there was one, the Four Seasons, with an attractive display outside.

The doorbell rang as she walked in and her entrance interrupted what sounded like a heated argument between a tall, fair-haired man she had seen somewhere before and the young woman behind the counter. Expecting to hear the local dialect, Imogen was surprised to recognise the familiar accent of home from the girl, and as the man made a hasty exit, Imogen saw that she was wearing the gold claddagh ring.

‘Can I help you, madam?’

‘Indeed you can, but you are a long way from home, are you not?’

The girl’s eyes widened. ‘I’m from Kerry. From Carasheen.’

Imogen leant over the counter and pointed to the claddagh. ‘I recognised your ring. I’m Imogen Crowe.’

A shriek of pure delight. ‘Dia dhuit, Imogen! We’re related. I’m Kathleen Crowe.’

‘Dia is Muire dhuit, Kathleen!’ Imogen replied in the Irish and held out her hand to Kathleen who took it and, smiling, touched Imogen’s third finger with the claddagh representing love, faith and loyalty. That was what Imogen had chosen in Dublin, rather than the normal plain gold wedding ring. The claddagh had been worn by all the Crowe family for generations past, as the traditional wedding band, and the two hands clasping a heart surmounted by a crown was said to have been worn since Roman times.

Anxiously, Imogen had told Faro of her choice and her reasons, afraid that he might object, but he wouldn’t have minded had she chosen a curtain ring as long as she had decided at last to be his wife:

‘You wear it with the crown pointing to the fingernail if you are married, and with the crown pointing downwards if you are unwed and on the lookout, so to speak. As it’s for both men and women, would you like one?’ But Faro declined; he had never worn rings and the claddagh, although looking so right on Imogen’s hand, he considered would be a mite ostentatious for him.

The Four Seasons was a busy shop with customers considering what flowers to buy, so in the briefest of conversations Imogen was hearing that Kathleen was a widow, her young sailor husband from Yorkshire, whom she met on a visit to Kerry, having drowned shortly after their marriage.

Kathleen, aware of customers now waiting for attention, smiled at them apologetically and whispered to Imogen:

‘I live just up the road there’ – she gave a vague gesture towards the residential area beyond the Stonegate − ‘but the shop closes at six,’ she added hurriedly. ‘There’s a tea shop across the road, see!’ She pointed through the window. ‘We could meet there.’

Imogen agreed. She could get a later train to Edinburgh. Spend the whole day here. This was too good a chance fate had thrown her way, on her first visit; an astonishing coincidence, discovering by pure chance that here in York was one of the vast tribe of Carasheen cousins she had met only once as a child, now working behind the counter in the Four Seasons flower shop.

She knew vaguely from her uncle Father Seamus that Kathleen had married an English sailor and by all accounts had settled in England, but this totally unexpected coincidence had taken both of them by surprise.

Apart from the weather, the sudden rain showers, she would spend the day exploring. After walking the Shambles, she discovered the Minster in circumstances almost divine. Her visit coinciding with the choir practising for evensong, their voices echoing in angel-like chorus through the vast spaces, now seemed to turn her meeting with Kathleen in the Stonegate into a blessing.

Imogen was enchanted; she had fallen in love with York at first sight and was more determined than ever to bring Faro, certain that he would share her feelings; they always loved − or occasionally hated – the same places.

Before settling down in their new home in Edinburgh, they would get to know York, have it provide the holiday both sorely needed after a trying winter. After this first visit she resolved to return again in three weeks, give Faro’s ankle a chance to mend properly, all the while bearing at the back of her mind the Hardys’ offer. However, in case that did not work out, she would book a suitable hotel.

As well as getting to know this city that had captivated her with its brief glimpses, a longer visit would give her a chance to get to know more about Kathleen Crowe, this long-lost relative, more than had been possible in a few moments before customers who had entered the busy shop waited impatiently to be served.

As the hour approached, Imogen wondered what that her next meeting would be like with no childhood remembrance, aware only that four-year-old Kathleen had been tragically bereaved when her father hanged himself in a Stirling jail awaiting trial as an Irish terrorist. Kathleen had looked near to tears, telling Imogen about her brief marriage and how, after her husband’s death, the wife of the boat’s owner had given her a home in York.

As six was striking melodiously with chimes echoing from all across the city, Imogen folded her umbrella, and pleased with the day’s activity of getting acquainted with York, but now footsore, was considerably heartened by the prospect of a cup of tea. Passing down the Stonegate, within sight of the Four Seasons, the ‘Closed’ sign on the door indicated that Kathleen would be waiting for her in the cafe across the way.

As she approached, she noticed through the window the empty tables, and trying the door, found it also closed.

She knocked timidly, and it was opened by a tall lady in smart black bombazine, her manner suggesting she might also be Mary who owned the cafe.

‘We’re closed, madam,’ she said firmly. ‘Sorry. Open again tomorrow morning at ten.’

As she made to shut the door again, Imogen said, ‘Excuse me. I was supposed to be meeting someone here – my cousin, works at the flower shop, over there. Perhaps she left a message for me?’

Mary Boyd frowned as she peered across the road. She shook her head. There had been no message left for anyone. ‘Are you sure this was the right cafe? We don’t do evenings, just light meals during the day. And we close at five.’

Regarding Imogen thoughtfully and realising she was most likely one of the many daily visitors to York, she said: ‘There are lots of nice cafes nearby, madam. Along the Stonegate, there’s The Owl Barn and …’

But Imogen wasn’t listening to the list. She shook her head stubbornly. ‘My cousin definitely stated this was the cafe, pointed it out to me. Perhaps you know her? Mrs Roxwell?’ she added hopefully.

Mary shook her head. ‘Don’t think we have ever met.’ And aware of Imogen’s bewildered expression she added: ‘We don’t get many shop girls in for coffee. It’s difficult getting breaks during the day, when you have to be there for customers. And it’s a bit expensive for the young girls, they usually bring their own food.’ She paused. ‘What does she look like?’

Having met Kathleen only once and so briefly, Imogen found her difficult to describe, just vaguely an ordinary young woman in her thirties, mid-height, brown hair.

Mary didn’t think she had ever seen her, she had never served her in the cafe and this girl, whoever she was, certainly hadn’t come in and left a note. She frowned. Surely working across the road she would be aware that the cafe closed at five, anyway.

It was useless to continue the discussion. There had been a mistake. Imogen apologised. Mary said again that she was sorry too. ‘When you’re a visitor,’ she added by way of consolation, ‘there’s so many places in York, you can get lost.’

The door closed. Imogen crossed the road and lingered outside the Four Seasons until half past six, then realising that Kathleen was not likely to turn up, taking out one of her cards, she scribbled a message with their new address at Preston Drove, saying she planned to return.

Heading back to the railway station and boarding the next train for Edinburgh, she felt uneasy.

‘Kathleen suggested the meeting, so why didn’t she turn up? She had sounded sure about times and everything, so what had happened?’ she said to Faro later, after recounting their extraordinary encounter and the events of her day in York, including her plan that they should have a holiday there. Although certain that Faro would love York, she did not mention the offer of accommodation at the Dower House, that was to be a surprise.

Faro agreed that York sounded quite perfect and had a list of consoling suggestions about Kathleen’s non-arrival, none of them of a serious nature but it continued to bother Imogen. She was certain Kathleen had meant to meet her and each day she hoped the postman would deliver some message, some explanation.

It never came. Kathleen remained silent.

CHAPTER FOUR

There was much to keep the Faros occupied during the following three weeks, moving into the new home, and again Imogen discovered that she would be travelling to York alone.

Faro had to attend the funeral of one of his former colleagues from the Edinburgh City Police. The timing was unfortunate, the afternoon of the day before they were to leave for York, while Imogen had written to Kathleen suggesting that they meet at the shop when it closed, planning to take her to the hotel where they were staying for supper, she told Faro. And to meet him, of course.

He agreed. ‘All things considered, I think you should go alone, and I will come on Wednesday. There will be people I haven’t met for ages after Mason’s funeral, as well as his family, and it would seem discourteous to rush away. Better if I take the York train next morning.’

Aware of her disappointed expression, he smiled. ‘Besides, this will give the two of you time together.’ In point of fact, this arrangement suited him well as he felt this meeting of the two cousins would be happier without his presence, since it would be overloaded with family news of Imogen’s relatives known to him as little more than names in Carasheen.

Imogen accepted his decision and, more aware of the reason for his reasons than he guessed, she set off on a bright sunny day, elated at the prospect not only of seeing Faro but of being with Kathleen again. The city’s history fascinated her; she felt all the excitement of opening a new project and determined to seize every opportunity, while Faro explored museums and art galleries, to research the conditions in women’s prisons in York, particularly since the bodies of three females had been discovered during excavations in the 1850s.

‘What is your man like?’

Gazing out of the window as the train sped past Durham heading for York, Imogen wondered how Faro would react to Kathleen, never able to conceal from her that he was always a little wary of her many relatives. She smiled at her own reflection as she remembered only one of Kathleen’s eager questions at that first meeting.

‘Uncle Seamus wrote that he’s from Orkney, isn’t he? I gather he’s a policeman you married, and I bet he is tall and handsome.’

Imogen had laughed rather proudly. ‘That describes him, more or less.’ Although she carried a photo taken in Edinburgh last year, no likeness ever did him justice. How could she or anyone else who knew Jeremy Faro, retired Chief Inspector of the Edinburgh City Police, now her husband, answer that question. Glancing down at her hand with its wedding ring, she had firmly resisted a traditional occasion with many guests, family and friends. Such a ceremony was against all her principles, to be thus publicly linked even to the man she had loved for these many years. Marriage was for them a private business and thankfully Faro agreed.

She sighed. The upcoming wedding at Elrigg Castle would be a very different affair based on traditional pomp and splendour.

‘He looks like a Viking,’ was all she had said to Kathleen, her standard reply to anyone who asked. Good looks, yes, but there were lots of handsome men − Faro had much more than the requirements fitting the description. No camera existed that could capture his physical strength, the fine brain, his integrity and sense of purpose that had led the young lad from Kirkwall in Orkney, to seek his fortune in Edinburgh and rise from constable to chief detective inspector to become a legend in his own lifetime.

She smiled to herself. Even fifty years later, he had never lost it.

She gazed out of the window through the train’s smoke, Durham with its magnificent castle briefly held the horizon. She made a mental note that was another place they must explore. An undulating landscape, flatter now, fields of sheep with young lambs whirling away from the smoking monster that thundered by.

More stations, platforms with anxious travellers, guarding luggage and small children.

‘Your ticket, miss.’ It was the train conductor.

Imogen frowned. This was his second time of asking. He had already seen the ticket when she boarded the train.

‘Is there something wrong?’ she asked as he handed it back. He shook his head, feeling guilty and a little ashamed. He gave her an appraising glance; didn’t see many beautiful women on this daily journey between Newcastle and York, and this one was a stunner, the temptation for another look at her irresistible. He thought fleetingly of his wife working in a laundry in York, their life untouched by any kind of beauty or magic like the young woman who looked as if she had stepped out of a fairy tale with her mass of dark red curls and green eyes. A lovely voice too, an educated woman, one of the toffs, and he wondered why she was travelling alone. This second closer look revealed that she wasn’t as young as he had first thought, a bit of a shock, she must be past forty and married. Lucky husband, he thought, closing the compartment door and sliding back into the swaying corridor of the train.

And now as the train steamed into York, Imogen gathered her luggage and stepped down on to the platform. Keen to have that promised look at the Dower House, she had sent the Hardys a telegram regarding the train’s arrival at midday, which would give her plenty of time to spend with them before meeting Kathleen when the Four Seasons closed. However, she had her first misgivings as the platform emptied.

Then she saw a figure waving, Belle’s smiling face.

She embraced Imogen and said: ‘Theo is waiting.’

And there he was, smiling happily at the wheel of their handsome motor car, a new Ford tourer.

Imogen soon realised that the motor car had made its debut and settled in York. As in cities like London, Edinburgh and Dublin, it was fast replacing the horse-drawn carriage. She was seated comfortably beside the eager to be friendly Belle, who she was to learn was a local lass. Holding Imogen’s hand and saying how wonderful it was to see her, Belle was asking where was her handsome husband.

‘We were so looking forward to welcoming you both.’

Imogen gave a brief explanation about the funeral and told her that he would be arriving tomorrow.

Belle was saying Theo was dying to meet Inspector Faro, had heard so much about him. Then she giggled and confessed that her broad accent worried her husband who secretly thought it a mite common, moving as he did amongst mostly academics, but Belle merely laughed at him. She told Imogen that she was proud of having no edge, as she called it, a Yorkshire woman born and bred.

During the drive it emerged that Theo was a clerk in charge of records, keeping track of digs and artefacts rather than a working archaeologist. There was a surprise in store as they arrived at the Dower House. Glimpsed only briefly through rain on Imogen’s first visit, it was not the kind of middle-class villa that might be expected as being within the means of an academic’s salary.

As well as owning the motor car, the Hardys’ residence was two centuries old, tucked away in the Irongate, a secluded cul-de-sac, a tiny oasis she had had such difficulty in finding on her first visit, hidden behind one of the Snickelways in the heart of the city. Like many ancient houses Imogen had encountered in her worldwide travels, it had an air of bewilderment, dwarfed by a city whose houses had sprung up alongside the old property, leaving it lost in time while the world around it moved on.

Now with leisure to regard her hosts more closely, she wondered again how the Hardys came to own and could afford the upkeep of such a mansion, which, as was pointed out to her, even possessed a private park.

The Hardys themselves were like many couples who had spent half of their lives together: blended by the passing years and approaching middle-age, few individual features remained to describe their personalities apart. Theo was tall, thin, balding and had never been a handsome man, but a distinguished scholarly manner hinted towards ambitions that at some time encompassed more than his present role as a mere clerk. Belle made up for his reserve with an air of faint but perpetual frivolity, the fading airs of a once pretty blonde with now thinning curls and abundant curves well controlled and corseted.

As Theo was handing Imogen out of the motor car, Belle was saying that the garden was older than the house. It was her pride and joy and they were looking forward to the pleasure of showing it to Imogen and her husband in some detail and at its best, in broad daylight, when Inspector Faro arrived.

Theo took up the story. ‘There is clear evidence of an earlier building, fragments of stone,’ he said excitedly. ‘The remains of a mosaic floor were unearthed twenty years ago, that and some crumbling stone ruins over yonder indicate a Roman villa existed on this very spot. Emperor Severus was over sixty when he came to York in 208 AD with his wife Julia Domna and two sons. He had a huge retinue of servants and soldiers, including the Praetorian Guard. He was the only black man ever to be a Roman Emperor, and it is believed that he lived in the villa here. When he died in 211 AD, York gave him a lavish funeral.’