2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

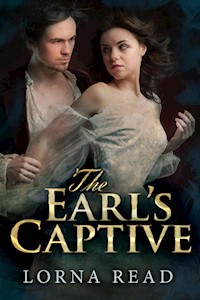

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

September, 1821. When her father announces that she must marry the ancient, grim-faced vicar, Lucy decides upon a desperate plan. Stealing his prized stallion, she escapes across the moors, only to fall into the hands of notorious horse thieves and the cheating arms of their rough but charming leader.

She is forced to take part in their crimes, but when she tries to deceive Philip, son of the Earl of Darwell, Lucy meets her match. Philip gives her an ultimatum: go to the gallows, or help him recover the deeds of Darwell Manor and his mother's lost jewels.

Now, Lucy has to win back her freedom while losing her heart to handsome, aloof Philip... who doesn't trust her an inch.

This book contains adult content and is not recommended for readers under the age of 18.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

The Earl's Captive

Lorna Read

Copyright (C) 2017 Lorna Read

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2019 by Next Chapter

Published 2019 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Chapter One

“No! Martin, not the child, she's just a baby. I don't care what you do to me, but … leave her, Martin. Oh Martin, no!”

Her mother's voice had risen to an agonized scream as a glancing blow from her father's tightly clenched fist caught her on the cheekbone and sent her reeling against the wooden dresser. A sturdy blue milk jug teetered and fell, smashing into irregular pieces on the tiled kitchen floor.

The moment was frozen forever into Lucy Swift's memory: the blow, the rocking jug, the white explosion on the floor, the sight of her mother on her knees, a crimson mark on her face already turning blue, sobbing as she picked up the sharp shards of pottery, and her father muttering an oath as he swayed unsteadily towards the door.

Looking at him now, hearing him whistle through his teeth as he brushed the bay mare into gleaming splendour with methodical, circular strokes, Lucy could hardly believe that the brutal drunkard and this careful, tender man were one and the same person – her father. Yet her earliest memory was no fantasy.

Similar scenes had been repeated time after time during the nineteen years of her life. They had driven her mother, Ann, into premature old age. At thirty-eight, she was grey-haired and haggard, her body shrunken as if by her efforts to protect herself from her husband's violent words and blows, her face lined and scarred from where he had once, during an exceptional bout of drunkenness, lashed her with a riding whip.

Lucy loved her mother with a fervour that had led her, from an early age, to stand up to Martin Swift. Once, at the age of four, she had rained blows on his knees with her childish fists as he sought to knock frail Ann aside, convinced that she was hiding a jug of ale from him. Her hot-blooded defence of her mother had often earned her a painful beating, but she knew she also had her father's grudging respect, especially where horses were concerned. Not like her brother, Geoffrey.

As if reading her thoughts, Martin Swift glanced from the fidgeting horse to his daughter.

“Bet Geoffrey wouldn't have made as good a job of it as this, eh?” he enquired, casting an admiring glance at his own handiwork. In the dusty yellow light of the stable, the pretty grey mare's hide gleamed like moonlight on snow. He didn't expect an answer, but dodged round to the other side of the horse and resumed his hypnotic brush strokes.

Lucy watched him while he worked. At forty-one years old, in spite of his over-indulgence in ale and spirits, Martin was in his prime, not a tall man, but wiry and strong, with the black hair and blue eyes that betrayed his Irish ancestry, although he, and his father before him, had been born in the same tiny Lancashire village where the Swifts still lived. Only his florid, weather-beaten complexion and broken nose bearing its route-map of tiny red veins gave a clue to his outdoor, rough-and-tumble life. Indoors, dressed up, with his body scrubbed clean of the smells of the stable, he could, in a low light, pass for the gentleman he thought himself to be.

Geoffrey was not a bit like his father, reflected Lucy, as she idly chewed on a piece of fresh straw. She missed her brother badly, even though it was three years since he had left Prebbledale, running away at fourteen to escape his father's bullying. She had aided his flight and she didn't regret it, even though she had, by this risky action, deprived herself of her staunchest supporter and closest confidant, probably for ever. For Geoffrey, dearest, kind, humorous Geoffrey, with his fair curls and poetic nature, was far more like his mother than either Lucy or Helen.

“That mewling little milksop,” was his father's usual derisive way of describing him. Born with a deep-seated fear of all large animals, Geoffrey would scurry for the nearest hiding place whenever his father came looking for him to take him into the stables and try to teach him some horse-lore. Martin Swift was known and respected all over the county and beyond for his skill in breeding, handling, breaking-in and training horses. Dukes and earls would send for him and ask his advice before parting with their money for a thoroughbred racehorse or a pair of carriage horses, knowing that his judgement was sound and unerring.

“No-o-o,” he would say slowly, shaking his head as some fine-looking specimen was paraded before him. “Not that one. Weak left hock. 'Twould let ye down over the half-mile.” And Lord Highfalutin' would wave the animal away and slip Martin a sovereign for saving him fifty.

The grey mare, Beauty Fayre, stamped a hoof and snorted, breaking Lucy's reverie. Who knew where Geoffrey was now? In the East Indies, maybe, having worked his passage on a trading ship; or perhaps he was dressed in the uniform of a naval rating, keeping the look-out while he mentally composed an ode to the heaving sea. Unless he was … Lucy couldn't bring herself to consider the worst fate of all.

A sound behind her, like the scuffling of a dog in the straw, made her turn her head. One shoulder and half an anxious face were poking round the corner of the cobwebby door-jamb as Ann Swift attempted to catch her daughter's eye without attracting the attention of her husband. Giving an almost imperceptible nod, Lucy took two silent steps backward towards the door and spun quickly round the corner of the building, trying not to catch her skirt on a protruding nail.

She had totally forgotten that her sister, together with her husband John and twin sons, Toby and Alexander, were paying them a visit that afternoon. Her heart sank at the thought of having to play auntie to the toddlers, cudgel her brains to think of something to reply to John's suggestive remarks and listen to her sister's predictable, boring grumbles about servants, children and the latest London fashions. It was always the same.

“Not married yet, our Lucy?” John would bark, in his brusque attempt at a jocular tone. She would wait to see the beads of sweat break out along his forehead as his eyes raked her lasciviously up and down.

“Really, Mother, I just cannot understand how Helen can put up with him. He's a beast,” Lucy complained to her mother.

“Shush, girl. He's a good man. She could have done a lot worse,” replied Ann in her quiet voice, like a defeated whisper. They'd had this conversation many times before. It was a ritual warm-up to all Helen's visits.

“But she'd never have married him, surely, if she hadn't wanted to get away from Father so badly,” Lucy persisted. “She was only sixteen. Who knows who she might have fallen in love with if only she'd had the chance? She didn't even know John Masters. Father fixed it all up. I think it's disgusting – like bringing a stallion to a mare.”

* * *

“Lucy!” Ann was shocked, but amused, too. Privately, she thought Lucy's outspoken opinion was quite correct. She reached out and straightened a roaming lock of Lucy's chestnut hair as the two of them sat side by side on the settle in the window, watching for the arrival of the visitors. How like her father Lucy was, with her straight back, her alert blue eyes, her plump, curving lips and her plain-speaking ways.

There was a vividness about Lucy that reminded Ann of her first-ever glimpse of Martin, as he stood in the marketplace of Weynford, her hometown, twenty-three years ago. To her, he had seemed to stand out from his companions as if surrounded by a kind of glow, undetectable to the human eye but nevertheless capable of being picked up by some sixth sense.

Even now, in spite of the years of torment and agony she had undergone at his hand, abuse that had caused her ill-health and a permanent nervous trembling, she was still in awe of him, still capable of feeling that same old wonderment whenever he looked at her kindly or gave her one of his special, half-cheeky, half-loving smiles. Whatever he possessed that gave him that unique power over people and animals, Lucy had inherited, and sometimes Ann feared for what life held in store for her younger daughter. Particularly now, with Martin so anxious about her unmarried state.

They had discussed it in bed just the previous night.

“Damn that kitchen maid!” Martin had expostulated, having sipped at his night-time beverage of warm ale only to find it stone cold. “Get rid of her, first thing tomorrow. And what are we going to do about Lucy?”

Ann, used to her husband's abrupt changes of subject, had sighed and withdrawn to the far side of the lumpy feather mattress, trying not to incur her husband's further wrath by drawing too many of the coverlets with her.

“Well?” he had snapped, reaching out in the darkness and digging his fingers painfully into her shoulder. “Well? Helen's twenty-one and she's got two fine sons already. I'm the laughing stock of the neighbourhood, having that strapping lass still on my hands at the age of nineteen. Why, only yesterday that cur Appleby had the damn' cheek to suggest that maybe nobody would have her because she was soiled goods. I whipped the blighter to teach him to hold his tongue. Still, an insult's an insult. She's been on our hands long enough, eating our food, taking up room about the place, striding round like a … like a great lad.”

Ann had felt a chuckle inside, knowing full well that Martin did treat his younger daughter almost exactly like a son. She knew, too, that Martin found Lucy a great help with the horses as she had inherited every bit of his own natural talent. Even unbroken horses calmed for her and let her approach them. It was as if some secret understanding passed between beast and girl. Sometimes she wished that Lucy had been born a boy. She would have gone far in life, of that Ann had no doubt – and that life would have been a lot easier, too.

Martin was continuing his monologue: “I've seen the way they all look at her – tradesmen, stable lads, respectable gentlemen. They'd all like to get their hands on her. We could have married her off twenty, thirty times already. If only I hadn't been so soft with her, giving in to her every time she said, 'No, Father, I won't marry him … No, Father, I don't like him …' Spoilt and wilful, that's what she is. Well, I've had enough. There's a good man I've got in mind for her. None better. She'll marry him and that'll be an end to it, even if I have to take the strap to her.”

Ann, with much nervous clutching and kneading of the bedclothes, had found the breath to whisper, “Who could this be?”

His answer had given her very mixed feelings indeed and caused her to lie awake the best part of the night. “Old Holy Joe. The Reverend Pritt.”

Chapter Two

“Here they come,” said Lucy, as John Masters' coach swept down the lane, pulled by a pair of matching bays. Masters was a wealthy grain merchant and Helen, as she stepped from the carriage, was, if not perfectly suited to her middle-aged husband, at least perfectly dressed.

The two little boys followed, identically dressed in blue jerkins and knickerbockers, their brown hair combed and twisted neatly into shape.

Binns, the maid, announced them breathlessly at the door, “Mr and Mrs Masters and the two Master Masters,” then flushed, as if realizing that what she'd said had sounded most peculiar.

“Thank you, Binns,” said Ann, rising to her feet. “We'll take tea in the drawing-room. And bring some apple cider for the children – watered, if you please.”

Ann was remembering one disastrous previous occasion when the maid before last had failed to water down the cider, resulting in two very dizzy small boys being sick all over the chaise longue.

“Yes, ma'am,” said Binns, dropping a brief, awkward curtsey and hastening out of the room as fasts as her lumpish legs could carry her.

“My dear,” breathed Ann, embracing Helen, who was taller than she was, and grazing her cheek on an amber brooch pinned to the shoulder of her daughter's short cape of the most fashionable shade of lavender blue.

Lucy felt her hackles rise as the portly figure of John Masters confronted her and she felt his hot gaze travel up and down her body. The crude sexuality of the man disgusted her. She was always having to dodge his groping hands and try not to blush at his suggestive remarks. She, who had never kissed a man except in polite greeting, could not conceive of her sister in the arms of this fat, ugly, lecherous old man, doing all the things you had to do in order to get with child.

Lucy's sexual knowledge was scanty but basic. Living in the country and working with horses as she did, she could hardly have avoided noticing the way they acted at certain times of the year. Her father always forbade her to leave the house when a stallion was put to one of his mares. What he didn't know, however, was that Lucy's bedroom was not the stronghold it appeared to be. An athletic person of either sex could, with a modicum of nimbleness, lower a leg from the windowsill, find a toehold in the crumbling, ivy-clad stone and from there, scramble sideways into the old oak tree, from whence it was a short and easy climb to the ground.

So, on more than one occasion, Lucy had heard the excited whinnying and snorting of the stallion and seen the mare, hump-backed and docile. Seen, too, the way in which her father and a helper aided the stallion by guiding that huge, terrifying, yet fascinating limb, thick as a man's leg, into the mare. Watching the frenzied couplings, Lucy had felt hot, breathless, faintly disgusted, yet tingling with strange sensations, much as she felt whenever a handsome man looked at her the way her brother-in-law did.

“I won't ask the usual question,” John Masters said, by way of greeting.

Lucy was surprised by this change in his usual tactics. Motioning her to sit in one of the two high-backed chairs that stood on either side of the marble fireplace, empty and screened now as it was a warm September afternoon, he stood in front of her, swaying to and fro, his fat legs crammed obscenely into his tight, shiny black boots.

“There's no need, is there?” he added, giving her a sly, conspiratorial wink with one corner of a weak, grey, piggy eye.

Lucy sat bolt upright. She took a deep breath, feeling how her tight stays constrained her lungs. “What on earth do you mean, brother John?” she demanded. Her words, spoken too loudly, cut across the currents of other people's conversations and stopped them dead. Helen, her mother, her father, even little Toby and Alexander from the privacy of their den beneath a table, were all staring at her, aware of the first rumblings of an emotional storm.

Lucy gulped and toyed with a bow on her cream silk dress. She wished she hadn't opened her mouth. Probably John had only been making a joke. He could not really be privy to some information concerning her future, about which she knew nothing.

Her brother-in-law's boots creaked as he shifted position uncomfortably. “Nothing. Um … that is…” He shifted his gaze to Lucy's father and she intercepted his glance.

So there was a plan afoot. Of course, she could have taken his remark to mean that there was no need to ask her if she were engaged yet because she obviously wasn't. But John Masters was a creature of habit, a mortal blessed with not one iota of imagination. He would only have made such a comment, and accompanied it with such a look and a wink, if he knew something which she didn't. After his There's no need, is there?, there had been a silent, unvoiced, Because it's all been settled.

They were all waiting, her mother brushing crumbs off her lap, her father working his toe into the rug, Helen pretending to straighten her necklace. A muffled giggle from one of the twins broke Lucy's tense trance and gave her back her voice. She directed the full, undiluted power of her iciest blue gaze on her father, who returned it equally coldly.

“Father, if any plans for my future have been made, I think I have a right to know what they are.”

“Very well, Lucy, but before you fly into one of your famous tempers –” Tempers? You're the last person on earth who can accuse anyone else of having a bad temper, thought Lucy furiously, wishing she were strong enough to pick her father up bodily and shake the truth out of him – “remember I am your father and head of this household, and as such, my decisions are not to be argued with. You're nineteen years old now, my girl. Nineteen!”

He looked triumphantly at everyone in turn and, backed up by their encouraging nods, turned to face Lucy again. “I can't wait for you to choose a suitor for yourself. I don't hold with such liberated notions. Allow a girl to pick for herself and she'll choose some ragamuffin with a roving eye and no'but two brass farthings to rub together.”

“Aye,” interjected John Masters approvingly.

His wife glared at him, but Lucy's gaze rested unwaveringly on her father, daring him to be a traitor and bestow her very own birthright of freedom and choice on some man she did not wish to know, and would detest if he were the King himself. Father, she willed, trying to project her thoughts behind his eyes and into the farthest recesses of his misguided brain, Father, I will not be married off. You can't do it. You will not do it. Her jaw was clenched in a spasm of steely purpose as she poured her whole being into her gaze.

But Martin Swift was untouched by his daughter's silent message. “Your mother and I love you and wish to do our very best for you. If you agree to marry the man I have in mind, not only will you live in comfort with a good man, but you will hold a very honorable position in the community, far higher than your mother or I could ever have hoped for.

“I had no idea that my daughter had caught the eye of such an august man as the Reverend Pritt. To be the wife of a man of God, Lucy! When I informed your sister and her husband in the hallway – well, I couldn't keep such a compliment to the family to myself, could I? – they were so pleased for you that …”

His voice seemed to be fading into the far distance, like the echo of a stone dropped into a dry well. At the same time, a mist formed in front of Lucy's eyes. She tried to pass her hand in front of her face, on which she could feel a cold, clammy perspiration forming, but her arm was like a lead weight and remained, unmoving, in her lap. Then a great lassitude overcame her and she felt her surroundings dissolve and her chair whirl like a spinning top.

Chapter Three

Lucy had never fainted before. She came to and found her mother hovering anxiously over her while her sister bathed her forehead in cool water from a basin held by Binns, the young maid.

“Don't you worry 'bout her, ma'am. She be herself right soon enough,” said Binns reassuringly. Lucy could have embraced her for her honest country forthrightness, but Binns, for all her commonsense, could not smooth the worried furrows from her mother's brow.

“My dear, are you all right? It is very hot today. You're not catching a fever, I hope?”

Helen's small, square hand in its cuff of pale blue lace touched Lucy's forehead, then her temples, and finally pulled down the lower lids of her eyes, making Lucy jerk back and blink in alarm. “The boys had a summer sickness some weeks ago,” Helen explained. “They went quite, quite pale under the lids. But there's nothing wrong with you.”

“I wish there was,” moaned Lucy fervently. “I'd sooner waste away and die than be married to that old … goat!”

* * *

Ann Swift drew a deep breath and chewed her lower lip thoughtfully. How she wished her younger daughter was as docile as Helen had been. She had gone to the altar with John Masters without a murmur and, indeed, the marriage seemed to be working. Helen had her boys and a good allowance and a husband who didn't beat her, even if he did sometimes respond rather over-enthusiastically to attractive members of the opposite sex.

At least this philandering tendency kept him from eternally bothering Helen with his attentions. He had done his duty, fathered twin heirs, and now Helen was free to attend to her duties of lady of the house and follower of fashion, something that pleased her far more than her husband's twice-monthly drunken fumblings in her bedroom. Even love-matches couldn't be relied upon to be perfect, as Ann knew to her cost. Yet, for Lucy, that is exactly what she would have wished – the perfect love-match for her beautiful, unruly, headstrong younger daughter.

* * *

“I won't do it,” announced Lucy, mutinously, waving away Binns's proffered glass of water. “I refuse to allow myself to be incarcerated in that damp prison of a rectory with that revolting, ugly, nasty-minded old man. 'Man of God' indeed! I would never take a young, sensitive child to hear one of our dear vicar's sermons. To hear him ranting about the terrible punishments God has in store for us all if we dare to defy His will or take His holy name in vain, makes me think that worshipping the Devil would be the easier option.”

“Leave the room, Binns. See how Cook is faring with the roast pork,” ordered Ann, terrified lest Lucy's blasphemies be prattled about all over the village.

But Lucy wasn't done. “Reverend Pritt has a very twisted idea of what God is really like. I think something very terrible must have happened to him in his life to make him turn his good Lord into the kind of enemy he would have us believe God is, someone who isn't kind and just and forgiving at all, but is a cruel tyrant – rather like Father.”

Helen clutched her sister's arm in the hope of distracting her from her subject, as it was obviously upsetting their mother, who was standing by the window, fanning herself agitatedly. But Lucy was not so easily deterred.

“I am sorry, Mother,” she continued, a softer note creeping into her voice. Lucy loved her mother dearly and the last thing she wanted to do was upset her, but, on the subject of her own life, with her whole future at stake, she felt she had to express her feelings, even if it meant coming out with a few home truths.

“I know you love Father, in spite of his vile temper and the anguish he's caused all of us. I am his dutiful daughter and have always done my best to obey him, but this is one thing that all the beatings on earth could not persuade me to do. He can beat me until I'm dead if he likes, but nobody will force me to share my life and, even worse, my bed, with that gospel-twisting, repellent old cadaver, Nathaniel Pritt!”

“Oh Lucy, see sense,” put in Helen, stroking her sister's curly hair as if calming one of her toddlers. “He must be sixty if he's a day. One night with you and he'll probably drop dead of an apoplexy. I bet you he's never touched a woman in his life!”

“And he's certainly not going to touch me!” Lucy exclaimed, brushing aside her sister's hand and swinging her legs off the couch. Her head swam a little as she put her feet to the ground and stood up, but she ignored her lingering weakness. Appalled by the way both her mother and sister were calmly complying with Martin's wishes, Lucy turned to them, appeal in her eyes.

“Can't you see, either of you? Can't you understand?” She fixed her gaze on her sister. “I'm of the same blood as you, we're kin – who could be closer? Yet you seem to be made of totally different stuff. Why are you so meek? Why is it that you don't mind having to share a house and your body with an old, fat man whom you don't love?”

She was pleased to notice Helen's eyes blaze for an instant as the barb of truth stung home. Turning to her mother, Lucy continued, in impassioned tones, “I know you can't stand up to Father. I know that, if you had done, either you'd be dead by now, or he would have turned you out. But you're both trapped. Trapped!”

Her voice was rising on a note of hysteria. The whole room, with its pictures, hangings, heavy, cumbersome furniture and dark-coloured floor-coverings, seemed to be exuding waves of hostile oppression. She paced the drawing-room carpet agitatedly. She had to make them see. What was wrong with them? Nobody, not even her father, had the right to do this to another human being, to order their life right down to whom they should marry and when.

She thought of Reverend Pritt, clutching his lectern and rocking back and forth while his congregation's ears were dinned with threats of being visited by plagues even unto the third and fourth generation, his gaunt face grey with stubble, his yellowed teeth spraying the unfortunates in the front pew with holy saliva. She imagined herself spread like a naked sacrifice on a white-sheeted bed surrounded by the mouldering walls and ragged tapestries of the vicarage, with the knobbly, grey, corpse-like body of Nathaniel Pritt kneeling over her, his fetid breath fanning her face, his obscene, maggot-like fingers about to touch her own warm, living flesh.

“No!” she screamed. “No! Mother, Helen, you've got to help me! Tell him it's impossible. I don't care that he's the vicar, I don't care about his position in society, I don't want to share it. I'd sooner marry an ostler, a highwayman, anybody! But I won't marry that… that …”

Words came to her mind, words she'd heard her father and the grooms use. However, before she could say anything more, the door burst open and in strode her father, glowering like a thundercloud.

“Martin!” cried Ann, rushing towards him and catching his elbow in an attempt to halt a physical attack on his errant daughter.

“Woman, leave me be!” snarled her husband, his face suffused with scarlet anger. He shook off her restraining hand so violently that Ann lost her balance and fell, dashing her head against the ornately carved leg of a side table.

“Mother – oh, Mother!” wailed Helen, rushing to Ann in a crackle of starched petticoats and kneeling over her prostrate form. “You've killed her, Father!”

Chapter Four

Her mother lay as still as a corpse on the floor, yet Lucy made no move towards her. With her father charging towards her, she didn't dare and she dodged round the back of a damask-covered armchair for protection.

Martin took two more furious strides towards her then stopped, and Lucy felt as if her heart had stopped, too. How she hated and feared him! Suddenly, she was a child again, screaming at him not to hurt her mother. Then she was a young girl being slapped across the face for some minor misdemeanour such as not having bid him a polite enough 'good morning'.

Now, she was almost as tall as he was and her will was equally as strong, even if her muscles were not. In many disagreements in the past she had given way, but not this time. It meant far too much to her.

“Well, madam,” hissed her father, with heavy sarcasm, “so we have a new head of the household, have we? One who thinks she can set rules for herself and all the other silly little bints in Christendom!”

Lucy noticed his fists spasmodically clenching and unclenching and steeled herself to expect the blow. Across the room, Helen was still kneeling and chafing her mother's temples, and against the tapestry-covered door, a silent observer, John Masters, was nonchalantly leaning, a smug leer plastered on his plump wet lips.

“So Miss High-and-Mighty thinks a vicar isn't good enough for her, is that it? She thinks to stamp her pretty foot and defy her father, who's only a stupid, tyrannical old man? 'Marry an ostler or a highwayman' indeed!”

Lucy's hand flew to her mouth. So he had overheard her incautious words. There was no escaping a punishment now. Her eyes flicked desperately round the room, to the door, the windows … Her long, full-skirted dress made it impossible to move fast enough to escape. Either he, or her brother-in-law, would stretch out a foot and trip her, or catch a handful of her dress and tear the delicate fabric. All she wanted to do was ascertain that her mother would recover and then fly out of the room, out of the house, to heaven-knows-where.

Across the room, Ann Swift made a low moaning noise and began to stir.

“Thanks be to God!” called Helen, tears streaming down her rouged and powdered face. “She's alive!”

Lucy unfroze and started to move towards her mother, but had scarcely taken two steps when her father grabbed her by the wrist and, with an adroit movement, thrust her face down across the arm of the armchair she been standing behind.

“Get off me!” Fury seethed in Lucy's brain. To be beaten by one's father in private was one thing, but here, front of her sister and her odious brother-in-law … Her father had his hand on her left shoulder and was forcing her painfully down. With a cat-like twist, she jerked her and sank her sharp teeth into his arm.

“Ouch!” Her father's cry of pain nearly deafened her as his mouth was so close to her ear.

The pressure on her shoulder was suddenly gone but as she made to spring to her feet, she heard a hated voice drawl laconically, “Whip the bitch.”

“John!” replied Helen sharply. “This is none of your business. You keep out of this.”

“Hold your tongue, wife, or you'll be getting a beating too. A good flogging never hurt a mare – aye, Martin?”

Lucy caught her breath in a sharp gasp as she saw the object that John was holding out to his father-in-law – a small riding switch with a thong made out of tough hide, knotted at the end. Before she could cry out in protest, her father stuck out his leg and upended her across it. In spite of her vigorous kicking, she felt her petticoats and skirt being hauled up.

How could he? Lucy had never felt so horrified and shamed in her life. The leather thong sang through the air three times, causing her to shudder in pain. The embroidery on the screen in front of the fireplace, of which she had an upside-down view, began to blur as tears misted her eyes. She hated her father. She would never forgive him for this.

She heard her mother's weak voice pleading, “That's enough, Martin.”

Her mother's intervention stayed his hand. The whipping suddenly ceased and Lucy stood up shakily, smoothing her skirts and pushing back her tangled hair.

“If you'd have been a boy, I wouldn't have stopped at three strokes. You deserved a dozen at least for that show of defiance. Now, I hope we'll have a bit more obedience from you, my girl.”

He paused to consult the French clock on the mantel-shelf. “I am expecting a visit from Reverend Pritt in just over an hour's time. He has already made it known to me that he is coming to ask for your hand in marriage. His own dear wife died many years ago, before he came to this parish, and he is a very lonely man who dearly wants children, which his first wife could not provide for him.

“Go and clean your face, girl. Helen can help you do your hair. I don't want the Reverend to think you are a slut with those unruly locks of yours. Put your best dress on, the blue one that makes you look like a girl rather than a stable-lad, and come downstairs when I call you. You are to behave to the vicar like a well-brought-up young lady. None of those bold stares, my lass, and no answering back. Just reply politely to any questions he may ask you – and of course you are to accept him. There is no question about that. Understood?”

“Yes, Father,” whispered Lucy, frightened of the sarcasm that might creep into her voice if she spoke any louder. She bowed her head and inclined her knee, then stood up and took stock of the rest of her family: of her mother, crouched on the settle in the window, face in hands, weeping silently; of her sister, pausing in the act of comforting Ann to give her sister a look which said, 'I had to go through it and now it's your turn'.

To her surprise, her brother-in-law was nowhere to be seen. She reflected that he had probably gone to check up on the twins who were, no doubt, being plied with buns in the kitchen by Binns and Cook. With the exception of her ill-used mother, Lucy despised the lot of them. Giving them a contemptuous glance, she swept out of the room.

Once in the safety of her bedchamber, she paused. She had less than an hour in which to devise a plan. Maybe she could think up some way of putting Nathaniel Pritt off her, by saying or doing something so subtle that he, but not her father, would detect it. Maybe she could say something about religion which would show him that she was not in accordance with his own strong-held beliefs. He would not want to take for a wife a woman who was not totally committed to his own beliefs.

Yes, that was it! If she could let slip some pagan idea, or some comment that had more in common with the Church of Rome than England, maybe he would see at once that she was not the stuff vicar's wives are made of.

There was a knock at the door, and Lucy started guiltily, as if the visitor, whoever it was, had been able to read her thoughts and was coming to assure her that there was no escaping her fate. But it was only Binns with a basin of warm water, which she placed on the marble dresser. Lucy gave her a grateful smile and dismissed her.

Alone again, she sank down onto the gold-embroidered coverlet of her bed and instantly stood up as the pain in her buttocks was so bad. On the other side of the room, next to the cupboard where she kept her clothes, was a long mirror in which she could see her image reflected from head to toe. She had grumbled when it was installed, insisting that she didn't mind what she looked like. However, her mother had prophesied that, as she got older, she would mind, and so the thing stood there, in its heavy gold-leafed oak frame. Lucy stepped before it and examined her reflection. She saw a tall girl, whose naturally pink and white complexion had no need of rouge, with loose chestnut curls tumbling down to her breasts, wearing a rumpled dress of cream satin and ruffles which she'd always hated because it was feminine in such a silly way.

If I were a witch, she thought venomously, I would take some witches' wax and, under a waning moon, I'd make a figurine of John Masters and stab it with a hatpin there (she imagined the pleasure of spearing him through the groin) and there (now his heart was pierced by a silver barb).

Suddenly, Lucy started. Surely her imagination wasn't that strong? For a moment, she thought she'd glimpsed the face of John Masters in the mirror. Dropping her skirts, she whirled round – and did indeed find herself face to face with her loathsome brother-in-law.

“A pretty sight,” he purred, his double chin sinking into his cream-coloured waistcoat. “But a few additions from myself would make it even prettier.”

“Get out of my room!” yelled Lucy, furious that her most intimate, private moment had been invaded. She advanced on the interloper, not quite sure what to do, but determined to wreak some damage on him. Like a tigress unsheathing her claws, her fingernails lashed towards his eyes. His arms went up and caught her hands and squeezed them until she squealed. “Let me go, you're hurting!”

“All in good time, little sister.”

“If I scream loud enough, Father, Mother, someone will hear,” she warned him, and inhaled to fill her lungs for the effort.

“But you won't, will you, Lucy?” he informed her, his small eyes in their puffy surrounds of fat boring into hers.

Lucy stared at him in surprise. She had long thought her brother-in-law to be cunning, but she had no idea what devious scheme he was working on now.

“You can yell all you like, my dear, but I doubt if you'll be heard. Your mother and sister are at the other end of the house, supervising refreshment for your … suitor.” He hissed the word with obvious enjoyment, reminding Lucy uncomfortably that time was running out for her.

“The children have been put to rest in the conservatory,” he continued, “and as for your father, he's in the cellar tasting the wine to help him decide which to offer the dear Reverend. So you see, my sweet, we are all alone. I sympathize with you, my dear. Reverend Pritt is an old toad, about as lusty as one of the tombs in his graveyard. It would not be right for your pretty body to go to him without a full-blooded man having enjoyed it first.”

“Let go of me!” Lucy demanded.

Pretending to swoon, she sagged limply onto the counterpane and then brought her knee up in one swift movement, but unfortunately missed the vital spot.

“You little bitch!” He gave her wrists a painful twist. “Give in gracefully, my girl, or I'll tell your father I saw you bare-arsed in the hayloft with one of the stable-lads.”

“But I didn't… I've never …” Lucy began.

“Who d'you think he'll believe?” Masters cut in. “You, who he knows to be a cheeky, devious little hussy, or me, his well-intentioned, honorable son-in-law? Do you really think your life would be worth living then? Don't you think he'd treble his attempts to get you married off before your reputation was in question, or your waist started to swell?”

He transferred his grasp on her wrists to one hand and used the other to grope for her breasts. Lucy twisted to left and right, trying to deflect his podgy fingers.

“Be sensible, Lucy, there's a good girl.”

Sensible? She would rather render him insensible!

“You're in a tight spot and maybe I'm the only one who can help you. Give yourself to me and I'll put in a good word with your father, try to convince him Pritt isn't the fellow for you, and that maybe I can find someone more suitable amongst my wealthy friends. I think the mention of money might make him see reason. And I know a lot of young studs who'd be a good match for a lusty young wench like you.”

As he groped at the skirt of her dress, there was a knock on the door and Binns's flat country tones could be heard saying, “Your father wants to know if you're ready, miss. The Reverend is expected in fifteen minutes.”

“Damn!” cursed Masters, swinging himself off the bed. “I never realized the old bastard would be here quite so soon. How long do you think he will stay? One hour? Two?”

“I don't know,” Lucy said. Right then, a couple of hours spent in the Reverend's company felt like sweet relief compared to whatever Masters might have in store for her.

“Well, I'll stay the evening and come to your room later. Remember what I said, sister dear. I'll put in a word for you if …”

Lucy nodded. Bending towards her, he pressed his lips on hers and Lucy shuddered in revulsion as it felt like kissing a slimy, dripping fish. Then he was out of her room with a wink and a leer, leaving her to collect her scattered wits.

Where was Helen, who was supposed to be helping her with her hair? Where, indeed, was Binns, who should have been dancing attendance on her, lacing her into her dress, proffering advice about this necklace or that, rather than just calling to her through the door? Lucy had never felt so alone, so abandoned, so confused.

Feeling dazed, she got up, reached in the cupboard for her blue dress and began, mechanically, to unfasten the cream one she was wearing. Then, struck by a sudden thought, she fastened it again and stepped quickly over to the window.

Outside, dusk was falling and low-flying swallows were dipping over the meadow at the back of the house. She had climbed out of the window before, but never in a dress as full as the one she was wearing. Still, she had no time to change.

Glancing up the hill, her eyes found, and rested on, the clump of sombre pine trees that surrounded the rambling old vicarage. It could have been her imagination, but she thought she spied a moving speck descending the hill path – Nathaniel Pritt on his trusty Welsh cob. There was no time to lose.

Pulling up her skirts and knotting them at the side, she unfastened the casement and swung her body out onto the ledge. She clung to the window sill as her feet found the familiar fork in the ivy. Then she was down it, on the tree branch, feeling her dress snagging on a hundred sharp twigs. She dropped lightly to the ground and glanced nervously all round her. She could hear distant voices from the parlour and the sound of her father shouting, but here, at the far corner of the house, all was quiet.