Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

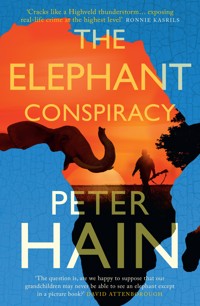

In the South African veld elephant herds are being callously killed for their ivory by murderous poachers. Fighting to save them, the Veteran and his team find themselves pitted against ruthless killers and wholesale political corruption. From conservation to politics, from bushveld to city, and from high finance to poaching this is a vivid and compelling journey into the competing worlds of activism and corruption. 'Lifts the lid on the ongoing threat to the endangered species' Daily Telegraph. 'Gripping, tense and timely' Alan Johnson

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 495

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

‘Cracks like a Highveld thunderstorm, hiss of a sniper’s bullet, rage of a hunted behemoth; exposing real-life crime, corruption and conspiracy at the highest level.’

Ronnie Kasrils, former ANC underground chief and Cabinet minister

‘Fascinating, riveting, authentic about the fight to preserve wildlife under siege from corruption and crime. Well done, again, Peter.’

Luthando Dziba, leading South African wildlife conservationist

‘Tense, unflinching, and viscerally evocative. Seeps with lived experience, redolent with the spellbinding qualities of Nature herself.’

Sarah Sultoon, The Source, The Shot

‘A gripping page-turner transporting the reader into the secretive, suspicious, perilous world of armed “dissident” Irish Republicanism.’

Marisa McGlinchey, author of Unfinished Businessii

Reviews for The Rhino Conspiracy

‘Lifts the lid on the ongoing threat to the endangered species’

Daily Telegraph

‘A brilliant thriller’

Georgina Godwin, Monocle Radio

‘Gripping, tense and timely’

Alan Johnson

‘Masterful … A thrilling journey behind the frontlines of the battle to save Africa’s wildlife’

Julian Rademeyer, author of Killing for Profit

‘A thrilling page-turner about the fight for humanity’

Zelda la Grange, Personal Assistant to Nelson Mandela

‘A true page-turner. A thriller that resonates with conscience, timeliness and deep knowledge of South African politics and wildlife.’

LoveReading

‘Compelling… an inspiring, yet moving novel’

Roy Noble, BBC Wales

‘A dynamic fast-paced thriller … it is emotional and compelling, educational and knowledgeable, exciting and bold’

Amy Aed, New Welsh Review

‘A novel that’s more than a thriller’

Socialist Worker

iii

THE ELEPHANT CONSPIRACY

corruption, assassination, extinction

Peter Hain

Sequel to The Rhino Conspiracy

‘Little did we suspect that our own people, when they got a chance, would be as corrupt as the apartheid regime. That is one of the things that has really hurt us.’

nelson mandela, 2001

‘The question is, are we happy to suppose that our grandchildren may never be able to see an elephant except in a picture book?’

sir david attenborough

‘If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse, and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.’

archbishop desmond tutu

For my grandchildren, Harry, Seren, Holly, Tesni, Cassian, Freya and Zachary Hain

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

He awoke instantly.

Rather like the wildlife in his care, Isaac Mkhize slept deeply when he felt safe – but the slightest danger jerked him immediately alert.

Never disturbed by normal sounds like traffic outside their apartment, or wind howling, or rain spattering, or even the whiffles of his wife, Thandi, lying peacefully beside him, sheet pulled down in the KwaZulu-Natal humidity, shimmering in the nightlight.

But this was an alien sound.

A rasp? A scrape? What was it?

Mkhize, his powerful bare torso tense, slipped silently out of their bed, pulled up his boxer shorts lying on the floor and listened. Another scrape, then movement – coming, he thought, from the living room of their compact two-bedroom second-floor flat – must have been the window, for it wasn’t the front door: that was securely locked as well as bolted inside.

He crept forward, crouching on his bulging thighs and muscled calves. More rustling, somebody moving almost as silently as him – he was sure now that was the strange sound. Creeping round their bedroom door he saw the rear of a man in the dark peering into the other bedroom that Thandi (and occasionally he) used as an office.

Just as the man was about to turn, Mkhize hit him hard in the base of his back, aiming for his solar plexus.

The man doubled up, shrieking with pain, turning in confusion, a stainless-steel knife glinting as it clattered to the floor, only for Mkhize to kick him in his testicles. Agony shooting through him, the man tumbled down in snarling shock. 2

Mkhize lunged forward, fist raised as if to smash him in the face, feeling as if possessed by something else, cold and resolute, ready to pulverise him. No man messed with his Thandi, certainly not this cowering thug.

The man bellowed, ‘No! No!’ still writhing, doubled up, and thrusting his hands up from his groin to protect his face in terror.

Then his eyes switched to stare, even more terrified, straight over Mkhize’s shoulder.

Thandi was standing there, stark in the dark, arms straight out, gripping in both hands the Makarov pistol the Veteran had given her – the way she’d been taught by him.

Woken by the commotion, she’d grabbed the gun from the bedside cupboard, hurriedly tried to snatch a tee-shirt but couldn’t find it, had crept forward.

‘Don’t!’ the man screamed, ‘He will send others!’

‘Who is “he”?’ Thandi shouted. ‘Who is “he”?’

The man shook his head. ‘No way will I tell you,’ repeating several times in Zulu, ‘No way will I tell you – he will kill me.’

‘I will kill you before he does – now!’ Thandi shouted.

The man shook his head, starting to sob.

Mkhize punched him again – this time on the chin, not too hard, not to knock him out, just to threaten him.

The man kept sobbing, shaking his head, muttering miserably, ‘He’ll kill me’, making Mkhize almost sorry for the thug, almost disgusted with himself for the violence he’d unleashed to protect his loved one: what sort of man had he become?

But Thandi, quivering – for she too had never done anything like this before – was absolutely fixated.

‘Tell me who he is, or I shoot,’ she said, the Makarov, to her utter surprise, steady as she pointed it at him, her finger on the trigger.

The man didn’t know if she was serious – and, in truth, she didn’t either.

Indeed, threatening to shoot a man with a gun, she wasn’t sure any more what sort of woman she had become.

It was as uncanny as it was moving. Without fail, each and every year.

Each and every year now for a while, at the same time, on the same day, the anniversary of her late husband’s sudden death, Elise would sit on her verandah overlooking Zama Zama Game Reserve to welcome them.

And they would always come, slowly and nobly, the mourning 3procession, paying their respects to the Owner, the one who had befriended them when they were raging, when they had arrived abused, their numbers callously reduced by poachers, ready to take on the world, to vent their fury at all and sundry.

The one who had cherished them, had slept in his tent in the bush alongside them, showed respect, showed that not all human beings were destroyers, not all human beings were cruel, not all human beings were heartless.

And then he had been taken from them – suddenly, shockingly, almost in the way they too had been slain, their family attacked. Out of the blue one day, their tranquil life ripped apart, several of their number assassinated.

So they always came at the allotted time to stand the other side of her garden fence and pay homage before Elise, the widow of their friend. The Matriarch would always lead them – she seemed suddenly frail this year for the first time, Elise noticed, concerned.

Imperious, dignified, gentle, respectful – yet ferocious if crossed – the Matriarch would tutor the young ones, swish them back into line if they shuffled friskily, teach them about the importance of the moment, that they probably wouldn’t have been there without the friendship of the Owner, that they needed to honour his memory too on this day of remembrance.

The tears ran down Elise’s finely shaped face, her blonde hair with encroaching silver streaks combed back smartly, hands folded on her knees over the smart dress, always the same one she would retrieve from its place in her wardrobe, hung there to be worn only for this occasion.

A mark of respect too for her to show to them.

And then, after a decent interval, the elephant herd would turn. Elise always searched for that moment when the Matriarch indicated to the others that their remembrance service was over, but could never spot it. They would move silently, even the babies for once obedient, and begin their slow, silent retreat behind the regal Matriarch, the constant din of the birds and cicadas for once eerily absent too.

‘Irish’ walked, steady and strong, his Armalite rifle ready as he searched for the target ahead.

The nickname ‘Irish’ had been Pádraig Murphy’s for as long as he could remember. Or at least since his teenager days in Crossmaglen in 4South Armagh in the far corner of Northern Ireland, the Irish border very near to both the west and the south of the small village.

Cool, damp South Armagh was dubbed ‘bandit country’ during ‘the Troubles’ – the decades of horror, of terrorist attacks and police and army counter-attacks, of assassinations, knee-cappings, bombings and shootings from the early 1970s.

He’d been born a few years earlier, and had grown up in a Republican family, in a community hating the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the British Army.

‘Irish’ suited him, he’d always thought, because that was what he was: ‘Irish’, not ‘Northern Irish’, not some little part of the United Kingdom, but Irish, part of Ireland. Not the ‘island of Ireland’ as the British Secretary of State always called it, carefully navigating the treacherous waters of language between Unionists and Republicans. But straightforward, unadulterated Ireland.

When he left school aged seventeen, having dropped out, to the disappointment of his teacher, who reckoned the youngster had university promise, there were no jobs beyond the most menial. Also, he was angry about the belligerent behaviour of British soldiers on the streets towards teenagers like him – they seemed to think they owned the place. And other grievances festered, like family and friends being arrested, their houses raided. So he drifted into the Provisional IRA – the ‘Provos’ – who ran everything in Crossmaglen. Everything.

And Irish was soon part of that: the attacks on the security forces, bombings, killings, smuggling across the border, post-office robberies – the lot, everything Republican paramilitaries undertook to keep their fight going: to drive the Brits right out of Northern Ireland.

Then he left the Provos, resigned from the 1st Battalion of the IRA’s South Armagh Brigade, disgusted by what he felt was its ‘sell-out’ to participate in Northern Ireland’s new inclusive self-government that followed the 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement negotiated by Prime Minister Tony Blair.

The 1st Battalion, covering Crossmaglen, Bessbrook, Forkhill and Camlough, had been one of the IRA’s most deadly, to the fore of the IRA campaign from the very beginning of the Troubles.

It wasn’t easy for him to resign – he left comradeship forged in crossfire – and instead joined an IRA splinter group with other dissidents. Suddenly, people he’d had known for years walked past, blanking him in 5the street. Local shopkeepers weren’t much better. He’d became an outsider, ‘one of them dissidents’. It made him even more determined, taking even more comfort from the beleaguered solidarity of his new ‘dissident’ network – not that hard, because most had been with him in the Provos.

Although nominally still living with his parents, he increasingly slept elsewhere, slipping out of alleys or farmyards through back doors into strange beds and sliding off again before light, sometimes never to meet his hosts. And never needing to worry any more about the six military watchtowers astride the mountain peaks from where the Brits had tried to spy on everything human that moved below, but now dismantled under the ‘peace process’ he despised.

In his heyday, Irish was known as ‘One Shot’ for his lethal sniper prowess, targeting Brit soldiers from their Crossmaglen barracks on foot patrols searching for Semtex or radio-controlled bombs in cowsheds, under bales of hay, in milk churns or wheelie bins, behind dry-stone walls, in ditches or gorse bushes.

But now he was on a very different mission, in a very different place, hot and dry, trudging forward, cradling his Armalite set on firing mode.

CHAPTER 1

After the new president had phoned inviting her to become one of his MPs, Thandi Matjeke spent a sleepless night, tossing and turning as she tried to make up her mind.

He had asked her to become an African National Congress Member of Parliament. Her? The President had specifically called to ask her? The reason, he had explained, was her courage and values demonstrated in exposing the Former President’s rhino conspiracy.

She’d called the Veteran, her mentor and former prominent ANC freedom fighter, for advice. But he’d insisted it was her choice, her decision. He couldn’t make it for her.

Neither could her husband, Isaac Mkhize. Her radio-production job was part-time, her activism all-consuming, his ranger job in the nearby Zama Zama Game Reserve taking him away for weeks at a time. Would they manage to make their young marriage work if she became an MP?

Did she really want to be one anyway?

Thandi had risen at five in the morning, fed up at being unable to sleep, still wrestling with her decision.

She was proud of being chosen by the President, and couldn’t help feeling flattered.

As the kettle boiled for her cup of tea, she had a small glass of pure aloe juice – always her first liquid of the morning, for its maximum health boost. Then she began preparing a bowl of Maltabella porridge; her mom, a big fan, explained to her that when she was a little girl, Maltabella, made from malted sorghum grain, was ‘like a warm hug in the morning’.

Thandi smiled at the memory, then jerked herself back to ponder. She 8knew she had a habit – no, a fault – of allowing her mind to flit when she really should be concentrating.

Being an MP would give her the prestige and the platform to push her ideas, maybe even be a route into government.

But she worried she would be beholden to the Party top brass, who chose the list of candidates and, critically, in what order: the higher, the better chance of being elected.

Which meant MPs were accountable to their party and not to their constituency voters.

And what if the President who wanted her was succeeded by a corrupt one who didn’t? Where would that leave her?

She was also repelled by the ANC’s milking of state coffers, its practice of eliciting a ‘donation’ from each state-owned enterprise, almost as if it was their patriotic duty. Taxpayers were effectively subsidising the ruling party and paying the salaries of its full-time officials.

That also fuelled factionalism in the ANC, as different groups in the Party competed not for politics but for salaried party positions to enrich themselves.

Some countries, Thandi had read, state-funded all parties according to their voting support – Britain did a bit, Germany quite a lot, Scandinavian countries even more. But their taxpayers contributed to all the major parties, not only one.

Under a quarter of a century of ANC rule, the lines between state and party had become blurred, and the professional integrity and independence of the civil service undermined.

Yet surely the ANC was different from South Africa’s other parties? It had led the transformation from tyranny to democracy, striven to unite a bitterly divided nation – to create a new country almost from scratch. Yes, it had become corrupt, but it also retained a noble mission.

Pondering all this, Thandi sipped her tea and ate her porridge, worrying and waiting for the President’s call.

She was still not finally decided.

Recently appointed head ranger, Isaac Mkhize established a new routine in Zama Zama. First job of the morning for the rangers not allocated to dawn bush walks was to hunt for snares. All the elaborate blood-ivory intrigues, all the cunning poacher plots, and yet snares were most regularly the biggest threat. 9

It was simple and quick for poachers to slide in, set a snare, retreat, find an elephant and sneak out again with a tusk bloodily hacked off. They hung wire nooses in wildlife corridors where unsuspecting elephants passing through the bush suddenly found their trunk or neck passing through the loop, and the more they twisted and turned to free themselves, the more the noose tightened, with escape rare, death slow. Snares were cheap and easy to fix, easy to plan. If the elephants were ‘lucky’ the snare might only catch an ear, and tear off a bit, or even wrench the whole ear right out.

No animal was safe from a snare. Small elephants were especially vulnerable to a concealed wire loop, one end usually fastened to the base of a stout tree. As the elephants struggled to free themselves, the snare tightened. If they managed to rip the end of the snare from its base, maybe assisted by their mother, that very act of freeing themselves tightened the snare tight around their necks, the ugly red wounds gaping and going septic, which for baby elephants could be life-threatening.

Most heart-wrenching were the three snared elephant calves Mkhize had once found, each under two years old and dependent upon their mothers for milk. The baby, barely nine months old, had a snare cutting deep into her neck and jaws, her trachea almost severed. The second, a bit older, had his neck encircled and his jaws somehow trapped. The third, getting on for two years, had a snare both cutting into her neck and one front leg. It meant that for all three even being nursed by the rangers, encouraged to drink or walk, was agonising – and complicated by their protective mums refusing to abandon them, hampering the treatment on the one hand but comforting the confused babies on the other.

Although his role in the anti-apartheid struggle had been modest, the Apparatchik was fond of exaggerating it, talking up how in his late teens the Soweto school students’ uprising in 1976 had first sparked his political interest, had led him to identify with the ANC, though so finding that its illegality made it difficult for him to join.

He claimed to be a founding member of the militant Congress of South African Students, though none of the actual founders could recall him.

His dashing anecdotes of James Bond-type behaviour, bigging-up his role in the ANC’s underground wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe, or ‘MK’, were derided by contemporaries. Much the same was true for his claims to have been a founder in the Free State region of the main resistance 10movement of the 1980s, the United Democratic Front. ‘He was nowhere to be seen,’ said one founder.

But his former comrades did recall one trait: a skill at pocketing a share of funds from donations to the ANC, invariably coming in cash because it was still an illegal organisation at the time and these couldn’t easily be made through bank accounts.

Nevertheless, impressive skills at football earned him his nickname ‘Star’, bringing him a charisma that he made the most of as he clambered energetically up the ANC ladder.

Star hailed from a small town called Vryburg ([free town)] in the then Orange Free State, or Vrystaat, as it was also known – the old Afrikaner heartland and former Boer republic situated between the Orange and the Vaal rivers. His home town had grid-patterned broad streets, still surrounded by flat, fertile farmland, with cows wandering on its pavements and a sign advertising ‘die beste biltong in die Vrystaat’.

As a boy, his preoccupation was getting enough to eat. His family came from the Basotho chiefdom, and he’d been subjected to the familiar myriad apartheid restrictions – from travelling on buses for blacks only to being banned from voting.

But the character flaws of exaggeration, self-promotion and slipperiness were to stand him in good stead as he advanced up a greasy political ladder to become provincial premier of what under him became known as a ‘gangster state’.

The new Security Minister, Major Yasmin Essop, was at a loss to know where on earth to begin in the mission with which the new President had entrusted her – to clean up and professionalise all branches of policing, security and intelligence, including her old fiefdom, military intelligence.

She had walked into a shambles: police officers committing crimes and others being sidelined for investigating those very crimes from the time when, ten years before, the Former President had appointed a new head of crime intelligence to do his bidding. Secret-service accounts were plundered to line pockets, and exploited to support crony politicians and their election campaigns.

Yasmin immediately appointed a new director-general after the old one had been exposed for receiving kickbacks from security contracts. She quickly ordered the arrest of the former head of crime intelligence 11on multiple charges, including murder, kidnapping, intimidation, fraud and perverting the course of justice.

She had uncovered evidence of illicit funding of private trips to China and Singapore, and home property conversions, as well as secret-service account looting. Procurement had also been corrupted through irregular and inflated costs of personal protective equipment. At one point, an acting head of crime intelligence had been plucked from among the Former President’s cronies on his personal protection team.

As was her habit, Yasmin spent a long time staring into space as she sat at her official desk, her new PA having quickly learned not to disturb her.

Yasmin never did anything on the spur of the moment. She calculated all the angles, she drilled down into all the details, as she plotted her path forward, computing who to pick off first in her corruption-riddled security services, operatives who would be the least able to mobilise pressure from the Former President’s still-powerful cronies determined to thwart the new president.

Inside the security services she had only a trusted few, including her loyal aide, the Corporal. Outside there was her freedom-struggle comrade from the 1980s, the Veteran, with his small band of activists: his protégé Thandi, the Sniper, who had played such an important role in the rhino conspiracy, and his British friend, Bob Richards.

Thandi continued fretting until the President finally called.

‘Good morning, how are you?’ His warm, friendly greeting made her feel even more embarrassed and defensive.

‘Good morning, sir, thank you for calling,’ she stammered.

‘Having slept on it, are you willing to join us? I certainly hope so!’

Thandi had worked out her response. She wouldn’t say yes or no until he’d answered her questions.

‘I am very honoured,’ she began. ‘In fact I am still astounded you called me in the first place, Mr President!’

He chuckled. ‘Not at all. You are a talented, brave young woman, Comrade Matjeke. We need you.’ His choice of ‘comrade’ was deliberate, to make her feel part of his ANC family.

‘Thank you, but can I ask a few questions, please?’

The President wasn’t sure whether to be irritated or impressed – probably both, he thought.

‘Of course,’ he replied. 12

‘Am I right that as an MP, my primary loyalty will be to the Party, not to the voters – and therefore if your successor as president doesn’t like me, or your corrupt opponents get total control of the ANC, then I’m finished, aren’t I?’

‘But the more people like you I can recruit, the less likely that will happen, Thandi,’ the President replied, sidestepping her question.

Although she had made up her mind, she didn’t want to offend him, still less to burn her bridges.

‘Mr President, I want to support you. I want all the corruption in the ANC to be rooted out, and I want you to succeed. Of course I do. But I have thought long and hard, and I think I can do that better from outside Parliament, where I am free from the clutches of corrupt ANC bosses.’

The President was taken aback. He wasn’t used to being refused. But although peeved, he also had to admit privately to a grudging admiration; he’d never come across anyone quite like this impressive young woman.

Before he could say anything, Thandi quickly followed up: ‘Can I please have a direct phone number in case I need to make contact if there is an emergency, so I can keep fighting for you outside the system?’

The President’s mind was already turning to his next of many tasks and duties. ‘I am very disappointed, Thandi. But of course, my political secretary, who is listening in on this call. will ring you right away with the numbers and emails you need. Meanwhile, go well, Thandi, and be careful about your personal security, because there are bad people out there.’

He rang off and Thandi put down her phone, pondering his last, rather ominous reference to her security.

Then she started shaking.

She had turned down the opportunity of a lifetime.

She’d said ‘no’ to the President!

And she couldn’t quite believe what she’d done.

Except that she felt an odd sense of relief.

The darkness was slowly fading and the dawn stealthily creeping up as Isaac Mkhize, rifle at his side, led half a dozen bleary-eyed visitors out of the lodge for their bush walk in the Zama Zama Game Reserve.

These ventures required full concentration, as the group was vulnerable to any predators and other wildlife they might stumble across. His colleague Steve Brown formed up the rear, keeping the excited visitors disciplined in line. 13

Mkhize had chatted to them over coffee and rusks beforehand, most half-awake, but one woman full of questions after her caffeine hit.

‘After all the international agreements, all the anti-poaching fortifications, are elephants still facing extinction?’ she’d asked.

‘Sadly, yes,’ Mkhize replied gravely. ‘Not so long ago, ivory-seeking poachers killed ten thousand elephants in Africa in just three years. During 2011 alone, about one of every twelve on the continent was murdered. Despite international bans on the trade, black-market prices are still extortionate. It’s heart-breaking: humans are such appalling killers.’

Bob Richards MP, not for the first time, was criticised for sticking his neck out.

London’s City Airport had been blockaded and Parliament Square jammed up by Extinction Rebellion protesters gluing themselves to pavements, roads and planes. Central London had almost been brought to a standstill.

Despite over 1,000 arrests, one MP attacked the police for being too soft. ‘I ate in a restaurant last night where there was only one occupied table. Normally the place is full, but people didn’t feel safe, so stayed away,’ he moaned.

Another was especially piqued at having ‘to step over’ XR protesters to get into her ministerial office.

Others fulminated about ‘a lawless mob’ causing chaos.

But to Richards, all this sounded like a scratchy old gramophone record, and he said so in a speech in the Commons, loudly heckled by several Tory MPs, to silence from his own front bench.

‘Give way!’ shouted several Tories as one rose to challenge Richards. He happily gave way, the clock timing his speech limited to five minutes – because so many MPs wanted to contribute to the debate – stopping at the intervention.

‘So the Honourable Member is advocating law-breaking! He’s a law-breaker!’ The MP looked around at his cheering colleagues on the government benches who chanted: ‘Law-breaker! Law-breaker!’

There was a resounding noise from the bellowing chants in the chamber, and the Speaker rose from his chair to shout: ‘Order! Order! The Honourable Member has a right to be heard!’

The chanting stopped, the Tory MPs giggling among themselves.

‘Mr Bob Richards!’ the Speaker called, gesturing to him. 14

Richards rose, but another Conservative MP immediately leapt to his feet.

‘Give way! Give way!’ his colleagues shouted again, sneaking a glance at the Speaker, just in case another reprimand was coming.

But Richards again willingly gave way, now angry but also content and determined to stay calm, thinking: he had them rattled.

The MP bellowed above the din: ‘Is the Labour front bench in lockstep with the Honourable Member’s law-breaking advocacy? Is this Labour’s new official policy? Is Labour now the “law-breakers’ party”?’

Tories gestured at the Labour front-bench spokeswoman, bellowing, cupping their hands, gesticulating, urging her to get to her feet and answer.

But she blanked them.

Richards stood, smiling now, which infuriated his opponents even more. They pointed and shouted at him as they looked anxiously at the Speaker.

Instead, Richards held his hands up, shooing them to be quiet, looking around for nearly twenty seconds until the din had subsided, before continuing, the clock ticking again.

‘A hundred years ago, exactly the same sort of outrage by male MPs and Lords was levelled at the suffragettes, who chained themselves to Parliament’s railings and caused all sorts of pandemonium. When Emily Wilding Davison died under the King’s horse at the 1913 Derby, racegoers in top hats were furious that their afternoon had been spoiled by her desperate protest for women to have the vote.

‘Two hundred years ago, the Tolpuddle Martyrs were arrested, tried and deported to Australia for the offence of forming a friendly society to provide help when they were poorly. The Martyrs were denounced as treasonable, lawless traitors, threatening the very future of England’s “Green and Pleasant Land”.

‘But workers then had no rights, weren’t allowed to join a trade union or strike.

‘Fifty years ago there was similar outraged condemnation when demonstrators invaded rugby and cricket pitches and to stop all-white South African sports tours at Twickenham, Lord’s and other grounds across Britain. “Civilisation was in mortal danger,” their critics cried.

‘But each of these groups shares an honourable heritage with Extinction Rebellion demonstrators. 15

‘A just cause, such as votes for women, better wages and conditions for workers, and the fundamental sporting principle that teams should be chosen on merit not on skin colour.

‘All were causes deploying tactics angrily denounced at the time in the newspapers, by politicians and judges. All were also causes only won after struggle and protest, sometimes bitter and confrontational.

‘But today the idea of denying women the vote is preposterous. The suffragettes are saluted. The Springbok captain is Siya Kolisi – a black man who would have been banned from representing his country under apartheid.

‘When I went to join Extinction Rebellion protesters occupying Whitehall outside 10 Downing Street, I found mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, singing about saving the planet, their numbers swelled by thousands of youngsters.

‘Far from being a “threat to civilisation”, they want to save human civilisation by demanding our government triggers action to combat the climate-change emergency now.

‘Of course none of us like it if we’re inconvenienced, but so long as governments like ours right across the world mouth platitudes instead of taking the radical action needed to halt and reverse climate change, we deserve to have our daily routines disrupted by the Extinction Rebels. Like most of us, I’m no climate-change angel – but I salute them.’

Richards sat down to harrumphs from his parliamentary opponents, who included (albeit silently) a few from his own party unhappy that he had given government ministers an opportunity, which they duly took, to denounce him for ‘advocating law-breaking’ and sundry other charges, instead of having to defend their decidedly underwhelming record on confronting climate change.

Although he’d been keeping a low profile since the rhino conspiracy, poacher-ringleader and former apartheid mercenary Piet van der Merwe still raged against the night.

The country was going to the dogs, he ranted.

The district municipality for the small town of Vryburg had admitted that a third of its wastewater treatment works were dysfunctional, and it now faced criminal charges after ignoring warnings, directives and notices to stop letting raw sewage flow into local streams and rivers.

Although aged infrastructure coupled with population growth had 16affected these sewer treatment works, Van der Merwe knew the real culprits were Star’s incompetent or corrupt cronies, appointed for their loyalty, with no expertise in running a water system.

Perpetual sewage spills in many of the rivers were causing a calamitous risk for agriculture, tourism and the people who lived in the area.

A series of Department of Water and Sanitation directives to fix their wastewater treatment works had been ignored; so had legal injunctions issued by local residents and businesses in the area.

The primary sewage pond in the town was overflowing, full of sludge and spilling raw sewage into the nearby river and its tributaries, causing them to become overgrown with green algae.

Sewage had also been pouring into the town’s natural wetlands with the stench unbearable. Some houses were surrounded by sewage, bits even bubbling through wooden floors. Local farmers complained about their dams going green, finding dead cows where they had drunk from them. There were worries that the systematic contamination of the area’s rivers would shut down the export fruit market.

Because of lack of maintenance, the wastewater works were in a continuous state of disrepair. Elementary duties, such as cleaning the screens designed to catch sanitary pads, nappies and other foreign objects in the sewers, were not done regularly, leading to the pumps burning out. Companies obtaining contracts to fix the pumps never delivered, simply pocketing the money, all paying a cut to Star’s fiefdom.

But faced with a tirade of complaints, he merely called an ANC rally to face down his critics, feted by his loyal party members, Van der Merwe shaking his head in disbelief.

That his paymaster had recently become the self-same Apparatchik quite passed him by.

Piet van der Merwe compartmentalised his life, and his thinking. A man had to earn a living. Yet a man still had a right to his own views.

An intriguing foursome, Bob Richards thought, joining the strictly private video conference initiated by Security Minister Yasmin Essop.

The Veteran – of course. The Sniper, present for his IT expertise and who mysteriously wasn’t named or introduced properly to Richards. Where should South Africa position itself on robotic weapons, Yasmin had asked. It was a topic Richards had become increasingly concerned about in respect of British policy. 17

‘Lots of key people are now saying that the future will be dominated by artificial intelligence, with serious worries about its military uses,’ the Sniper began.

He paused, having learned to allow lay people time to understand the issues underlying his world of fast-moving technology.

‘The heart of the problem is the introduction of AI into weapons. The whole point about having weapons is deterrence, not to fight wars but to deter others, because potential enemies know you have the capability to badly damage or even destroy them.’

The Sniper paused again.

‘But weaponising AI could even things up. How would we really know what our enemy is capable of if we all have access, as we surely will, and even do now, to AI-controlled weapons? Will our military strategists even have the ability to out-think or out-predict robotic weapons? And remember, wars sometimes have originated from mistrust and miscalculation.’

‘I’m not sure I fully understand what you’re getting at,’ the Veteran interjected. He’d never been afraid to ask a question even if it might signal ignorance. It was a sign of confidence to do so, not weakness – yet most people stayed silent, in case they might be embarrassed.

The Sniper pondered for a moment. ‘Remember the new Google program of a year or so ago that taught itself to play chess in a few hours? It was able to beat all previous programs and all human chess players. The point is that it was able to itself invent new chess strategies unknown in two thousand years of the game. Now apply that sort of AI power, if you like non-human logic, to weapons and we are in a whole new and menacing world.’

The Veteran, trying to understand fully, asked: ‘Wasn’t it a few years ago that top scientists like Stephen Hawking argued that AI was now the biggest threat facing humankind, maybe even bigger than climate change, and one that could finish us?’

‘Yes, exactly,’ the Sniper observed pointedly.

Yasmin interjected: ‘But the United Nations Secretary-General has urged states to prohibit weapons systems that could, all by themselves, target and attack human beings. He called them “morally repugnant and politically unacceptable”.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Richards. ‘We should press for killer robots to be banned by a new global treaty like the ones that prohibited antipersonnel 18landmines in 1997 and cluster munitions in 2008. Have a look at the film Slaughterbots. There’s a scene where killer robots swarm into a classroom, flooding in through windows and vents, students inside screaming as they are relentlessly killed.’

‘But,’ Yasmin interjected, ‘China, Israel, Russia, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States have been developing different autonomous weapons systems, as well as other countries. Can South Africa afford to get left behind in a killer-robot race?’

Richards bristled. ‘Since 2013, thirty countries have called for a ban on fully autonomous weapons: from Argentina to Austria, Brazil to Ghana. So quite a spread. Also the Non-Aligned Movement of over a hundred and twenty member states has called for international prohibitions.’

The Sniper explained: ‘Drones have been made that not only identify human targets but decide for themselves whether to attack. The technology already exists to combine AI with facial recognition, so drones can target a particular person, or even type of person like an ethnic group. Fighter planes piloted by AI could soon outperform human pilots. Like it or not, we are in a race that no country wants to lose, to build robotic weapons that are far superior to human-controlled ones.’

Yasmin was growing weary. She’d had enough of all this chat. ‘Remember the Soviet radar operator who spotted a sign of US nuclear missiles being launched in 1983 but did not alert his superiors because he wasn’t absolutely sure. Just as well, because the “launches” he’d spotted turned out to be rare reflections of the sun on clouds. It was a very narrow escape from triggering a nuclear war. Just imagine what a fully automated warning system might have triggered.’

‘Yes,’ Richards, said, ‘but there’s big resistance from the global military powers to any new treaty stopping AI weapons. They don’t want to risk being left behind. Others say AI systems can even save lives. The UK has said that because intelligent weapons are more accurate, there will be lower casualties, especially among civilians caught in the crossfire. The trouble is, we are heading for defence systems based on a hair-trigger controlled by each country’s own AI – and where will that end?’

The Veteran hadn’t said much, just listened intently, and now intervened: ‘You cannot expect countries to unilaterally give up on AI weapons when every other aspect of our lives, from medical treatments to manufacturing, are starting to use AI more and more. Surely we need an urgent global agreement at least to prevent AI operating nuclear arsenals? 19That’s the absolute minimum surely? This is not about science fiction any more. Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin has stated: “Who leads in AI will rule the world.”’

Yasmin nodded, making a special note among her scribbled points from the exchange.

‘Thanks, guys,’ she summed up drily. ‘Lots of food for thought when I brief the President, as he’s asked me to do.’

Star had honed his factional party skills ruthlessly.

His ANC organisational motto was simple: ‘If you control sufficient local branches, you can control a region. If you can control sufficient regions, you can control a province. If you can control sufficient provinces, you can control the national party.’

In the Free State, various irregularities were deployed by his acolytes, such as convening ANC branch meetings at short notice or at secretive locations, or ensuring members did not appear on branch registers, so were unable to participate. Rogue behaviour and vote rigging became the norm. Not surprisingly, Star’s grip tightened remorselessly.

But his party machinations had one purpose only: not to offer a different policy agenda to assist local citizens, instead to get control of the provincial coffers and loot them.

When he was put in charge of the Free State’s department of tourism, auditors brought in by the provincial premier found irregular loans and gross overpayment for goods, fraud and dodgy contracts. Then President Nelson Mandela tried to adjudicate and resolve from afar the intra-party infighting Star was pursuing to grab total power. Eventually, the ANC leadership dissolved the Free State executive and Star was first cast into the wilderness, then reinstated and shoehorned in as an MP.

But, kicking his heels in Cape Town as an obscure backbencher in Parliament, Star was all the time plotting to return to his province, where he succeeded in winning and holding the Party chairpersonship for a decade. The door was opened to his prize: the provincial premiership, where he quickly established an iron grip.

Soon its purpose became transparent. Heists of meat and vegetables through the Free State department of agriculture became commonplace when he was MEC (member of the executive council) for agriculture. There were also kickbacks from property developers and public contracts. Star used government resources to buy people and build 20his provincial empire just as he had built his party empire to get his hands on power.

But to keep that iron grip and its gateway into wholesale looting of provincial coffers, anybody in his way was threatened with demotion or suspension. There were suspicious deaths too.

The Scorpions – the crack security unit established to replace a crooked apartheid police system, which had been geared more to crushing political opponents than to catching criminals – tried to arrest him for corrupt sale of land. But before the Scorpions could execute their arrest warrant, Star’s close ally, the Former President, had conveniently ordered the unit be disbanded in 2009, substituting the ineffectual Hawks headed by his cronies.

Star’s circle was protected as serious crime soared.

She chuckled wistfully, her voice getting fainter at the effort of talking to her granddaughter Thandi, for her health had been deteriorating.

‘I remember back in the early 1963 when I again opened the door to be confronted by the same two large security police officers who had arrested the mother activist – two sergeants in the Special Branch, big fat men, one we called “banana fingers” because he had such huge, spongy hands. They gave the mother activist a banning order for five years.’

‘What was it like being “banned”, Granny?’ Thandi asked the old lady, who was slumped in her chair in the small sitting room.

‘It was thousands on words of paper: I didn’t understand it all, my reading wasn’t that good. But it stopped her meeting more than one person at a time. She couldn’t leave Pretoria and it stopped her from going to all sorts of places like black townships or courts, which she often visited for her anti-apartheid work. She couldn’t even go into her children’s schools to talk to their teachers – they had to come and stand outside on the pavement. And of course she was banned from taking part in politics, and had to step down as a local leader in the resistance.’

‘So what did she do then?’ Thandi asked, always in awe of the women who had joined the anti-apartheid struggle, been banned, jailed or, like Nelson Mandela’s wife, Winnie, banished to faraway places.

‘Aah, now Thandi,’ the old lady wheezed, short of breath. ‘The mother activist was a clever one. She found all sorts of ways to remain active secretly. She kept in daily contact with her successor as the local party branch secretary. He would call her from a phone box on the street with 21a coded message. Like “how is your dog?” When she didn’t even have one!’ The old lady cackled, then caught herself as she started to cough, before continuing. ‘That would be the signal for her to jump in the car and drive to a prearranged meeting point.’

‘Didn’t she ever get found out?’

‘Never. She ran rings around the Special Branch. We just called them “the Branch”. Once she suddenly asked me to go home in the middle of the week – very unusual because I normally only went home for weekends. When I returned, it was obvious someone had slept in my little bedroom by the garage. But I didn’t ask her about it. Not because she didn’t trust me, but best not to know.’

Old Mrs Matjeke winked, a small, conspiratorial smile on her creased, weathered face.

‘Did you ever find out why, Granny?’

‘Yes, but only a year later when the same thing happened. A political prisoner had escaped and asked her for help. She smuggled him into my room over the back of the kopje and drove him out in her car, squeezed into the boot, past the Special Branch parked on the roadside outside. Very brave, because if they had found the prisoner, she would have been put in jail.’

‘I suppose it must have been sort of exciting and horrifying all at once, this struggle activism, Granny?’ Thandi asked

‘Yes, exactly that. But I wouldn’t have missed it.’

The old lady was tiring now and Thandi helped her to her bed to sleep, quietly letting herself out of the small square brick house, locking up and pushing the key back through the letter slot in the door so her granny was safe.

Thinking back to that time – over ten years ago, when she was in her mid-teens – Thandi wondered what her granny would have made of yet more evidence of corrupt incompetence, this time of imploding health provision in the Eastern Cape, with one of the highest death rates in the world – more than 500 per 100,000.

Six newborn babies had died in a few days, specialist services for children with cancer were collapsing, and the Eastern Cape health department was about to run out of money.

Because of hospital-acquired infections in a shockingly overcrowded neonatal unit, one nurse sometimes had to look after twenty-eight babies. Another hospital was only able to provide four intensive-care beds and 22did not have enough doctors or money to provide twenty-four-hour medical care.

A paediatric oncology unit was facing closure because dire staff shortages made it unsafe to treat children there. Doctors warned that public hospitals were running on empty, with crippling staff shortages of nurses, doctors and specialists, and there were outbreaks of infections with multi-antibiotic-resistant organisms.

‘Wherever you look,’ Thandi complained to her husband, Isaac, ‘you find the horrible results of all the looting and cronyism under the Former President.’

Star quickly saw the Free State’s housing budget as an ideal source through which his friends and associates could get the most lucrative housing contracts, often cutting standards, with companies added to the approved database without national home-builder registration.

They all stuffed their pockets. He also put his cronies into the province’s spending departments to ensure billions of rands in national government grants were splurged on favoured cronies who gave him kickbacks.

Free State MECs were peremptorily sacked if they strayed from Star’s gravy train or had the temerity to challenge him. At a national level, senior ANC figures were sacked by the Former President if they threatened to expose Star.

When the Special Investigating Unit referred its findings to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), which in turn referred matters on to the ineffectual Hawks, a mountain of cases piled up with no resolution.

The Auditor General had identified billions of irregular payments in Star’s Free State, but nothing was ever done about it, and no politician or official was ever held to account for what amounted to a housing rip-off.

Star bulldozed through laws, procedures, checks and balances, always carrying wads of cash on him to dish out rewards. Any businessman who won contracts from his administration was obliged to make donations to the Free State ANC – except that many of these disappeared into favoured pockets rather than into party coffers.

Local media was also captured. Any journalists digging about were threatened and intimidated. Those carrying pro-Star stories were rewarded, so too were crony columnists – especially those who attacked his critics. Millions were channelled via Free State administration adverts 23to compliant media, nothing to critical media. When the former finance minister tried to pursue a Treasury investigation, he was blocked by the Former President, who was witnessed consorting with Star at regular parties and annual Diwali celebrations staged by the Former President’s fellow conspirators, the Business Brothers.

Star’s closest aides also racked up huge bills in hotels and restaurants, allegedly for official business but in fact for jollies. Meanwhile, young women associates, known as ‘Star’s girls’, set up consultancies that provided services to the Free State government as well as decidedly non-consultancy services to him, his wife pretending not to know as she lavishly decorated their home, entertained her friends with champagne and outside caterers, and focused on their grandchildren.

Pádraig Murphy’s New IRA – by then the largest of the breakaway Irish Republican ‘dissident’ groups – had become pretty promiscuous with its alliances.

Not so much for political objectives, but out of expediency, including for acquiring arms, mortars, assault rifles and bomb-making equipment. Hezbollah and other radical organisations in the Middle East, for instance, had provided the New IRA with weapons and financial support, not out of any ideological affinity but on the familiar basis that ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’.

That was in contrast to its ‘parent’, the principal Republican paramilitary force of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, the Provisional IRA, which forged alliances on a political basis. Before it laid down its arms in 2005 as part of peace-process negotiations, the Provos linked up with Spain’s Basque paramilitary group ETA and the Palestine Liberation Organization. And, from the 1990s onwards, with the ANC for insights on a peace and negotiating strategy to replace bombs and bullets.

ANC leaders such as Cyril Ramaphosa and Ronnie Kasrils had worked with Sinn Féin and leaders of the IRA to encourage its rank and file to embrace peace because inclusive negotiations had been offered by Britain for the first time, especially under Tony Blair’s government from 1997.

Which is where Murphy had first bumped into the Apparatchik on the periphery of an event, and struck up a friendship which, a couple of decades later, got called in.

By then, around twenty years after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, 24Murphy had long left the mainstream Provisional IRA in disgust at what he and others felt was a ‘sell-out’ of Republican principles.

The final straw was when Sinn Féin, with the support of the IRA leadership, signed up to support policing and the rule of law as a prelude to an agreement with their bitter old Unionist enemies to share power on a self-governing basis for Northern Ireland.

The Sinn Féin leadership argued that, since policing and justice would be devolved and would no longer be under the supervision of the Brits but their own new self-government, it would not be run by the British state and it was therefore no longer tenable for Republicans to oppose it.

At a meeting in early 2007 in West Belfast’s Clonard Monastery, there were heated exchanges, with Pádraig Murphy and his cohort standing at the back of the church shouting ‘traitor’ at the Sinn Féin politicians speaking from the altar, one woman walking out muttering at them, ‘My son didn’t die for this.’

For Murphy it was the end. He joined the small breakaway New IRA, finding himself and his colleagues on the receiving end of that very toxic label used by Sinn Féin leaders, who denounced him and his ilk as ‘traitors to the island of Ireland’ after the New IRA had killed a Catholic police constable.

It was a watershed moment, revealing the vicious divide within modern Republicanism, and signified Pádraig Murphy’s final self-banishment from mainstream Republicanism into the cold of the marginalised fringe.

When she focused on a subject – and she was known for flitting about, her attention wandering between all the many subjects catching her interest – Thandi could be relentless.

She’d pulled his leg, always did, accusing him of loving his elephants more than her.

‘Come on, Isaac,’ Thandi chided, ‘tell me why – why you worship elephants so much.’

‘What do you mean?’ he bristled, only for show, rather enjoying her banter with a purpose.

‘Well, like their intelligence for instance, and why they are so important to you – to all of us.’

‘Okay,’ Mkhize paused, thinking what information would best help for her latest mission.

‘First of all, African elephants have an incredible sensitivity – much, 25much better than humans. Even from many kilometres away, they can smell food. They also hear sounds, far below human ear range, for long-distance communication, and read earth vibrations transmitted over very long distances. If they feel or hear seismic activity caused by humans – like building new roads or drilling for minerals – they will flee.’

‘How does this happen?’ asked Thandi.

‘Some scientists think they receive vibrations through bones in their legs transmitted to their inner ears. Others believe they have pressure sensors in their feet. They may be able to detect other elephants, thunderstorms and human-made noises from very far away through sounds that are inaudible to humans.’

‘Elephants are also eco-animals. When they feed, forest elephants open up gaps in vegetation allowing new plants to grow and also pathways for smaller animals, and their piles of dung are full of seeds from the plants they eat, boosting local diversity of grass, bush and trees.’

‘And poachers are their biggest enemy?’

‘Yes. But the threat to elephants is not only from poachers. Humans are crowding them out of their traditional habitats, through housing, farming, roads, railways and pipelines. Which means elephants then start to attack farmers’ crops and compete with people and livestock for land and grass.’

‘Trees are really important to elephants, not just for food but for shade, and they rest there during the heat of the day, trying to keep cool. Because they are so enormous, they can get really hot, and African elephants flap their large ears, which are full of blood vessels to cool themselves too.’

‘So are they really heading for extinction?’ Thandi asked.

‘Yes,’ Mkhize replied gloomily. ‘Their ivory gets very high prices, especially in East Asian countries, where it is a big status symbol.’

CHAPTER 2

The local Vryburg councillor laid down his knife and fork and rose from the kitchen table in the cramped box-like house as his wife expressed irritation, having just dished out the food she’d cooked.

The eldest of their three young daughters had asked: ‘Who’s that knocking, Dad?’

It was dark outside, but locals frequently bothered him about this or that – any time of the day, any day of the week. He didn’t mind, saw it as part his duty.

The door was stiff, and scraped sharply as he dragged it open, peering into the night.

A balaclava-clad figure stood menacingly before him.

Before the stunned councillor could say anything, the figure raised his arm and levelled a pistol.

In the kitchen they heard two shots, which seemed almost to lift their tiny home off its concrete base as it shuddered with the impact.

Pandemonium.

The eldest girl ran towards the front door shouting, ‘Dad! Dad!’, her terrified mother screaming, ‘Come back! Come back!’

She found her father slumped, shrieking piercingly, clutching both his thighs, as silent Balaclava Man walked away, not even looking back, unfazed as to whether any of the neighbours saw him, a henchman protected.

Job done. Another nuisance dealt with. Instructions carried out to the letter. Not to kill, instead to hurt.

Anybody who got in Star’s way faced a blunt choice: either to back off or to be disposed of, for he brooked absolutely no alternative. So it proved 27for the local councillor, who had begun asking questions about a large fenced-off area spanning fifty square kilometres outside Vryburg. Who was behind the new company ‘Vryburg Enterprises’, which had been awarded the central government contract to run a new business promising desperately needed new jobs to local people? Agricultural workers, the word was. But exactly what experience did its directors and executives have of turning such a large area beside the Vaal River into something productive? And so on.

All normal questions, normally easily answered.

But not this time. Maybe not ever – for the local councillor certainly wasn’t going to ask anything like that ever again.

As for the local police, they shrugged, disinterested. In their ‘gangster state’ they knew who was in charge. And who never to cross.

Except that, as the councillor, writhing in pain, was lifted into an ambulance to be rushed to hospital, he called his wife over, whispering to her: ‘Call my dad – tell him what happened; tell him to call his old comrade from the freedom-struggle days.’

Distraught and hardly able to think straight, she did exactly that.

And Star couldn’t have known that the local councillor’s father, Jacob Kubeka, had kept loosely in touch with someone with whom he had formed a bond during the ANC’s guerrilla war against the armed might of the apartheid state.

And that man, known these days as ‘the Veteran’, had helped strike a mortal blow against Star’s mafia-like godfather, the Former President, barely a year before.

Had he been aware, even Star would have flinched. Instead, he was blissfully enjoying the report that another busybody had been dealt with.

On her way to work in Richards Bay, Thandi crammed into one of the ubiquitous African minibuses serving as taxis, long ago colloquially labelled ‘Zola Budds’ after the 1980s bare-footed South African sprinter.

While the other passengers chatted among themselves, she was silent, daunted by the sense of heaviness that had descended upon her young shoulders.

‘Hey sister! Cheer up! You could come with me for a nice time!’

One of the youths in the taxi leered at her, his mates urging him on.

‘Go for it, bro!’

‘She’s so miserable she needs a cool dude to snuggle up to!’ 28

Thandi blanked the lot of them, though everyone was jammed in so tight the youths were hard to ignore.

The taunts continued, the jibes got more raucous, the cackling louder, the mood uglier.

Thandi tensed, knowing from her past that a confrontation was now inevitable because she would never submit to them.

‘She’s a bitch!’

‘No, she’s a dyke!’

‘Nah, man, she’s a virgin!’

‘She’s never enjoyed a real man!’