8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Periscope

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

It begins with an explosion. In a small American town in the 1930s, Amos - a quiet giant of a man with a heroic spirit and a troubled past - is partly blinded in a locomotive accident. Aubrey, a sheltered boy of eleven whose patrician New England family employs Amos as a handyman, rushes to his aid. As though heralding the twentieth century's worst cataclysm, this disaster inaugurates an epic story of war, friendship, synchronicity, courage and despair. Over the next ten years, in the mountains and forests of North America and on the bloody battlefields of Europe, Amos's and Aubrey's trajectories will converge mysteriously. Although they inhabit very different worlds, these chance meetings deepen their bond each time, and will shape each of their lives in profound ways. The Eye of the Day boasts a sweeping scope and a rich cast of characters that ranges from tragic, dispossessed souls to some of the most illustrious (and notorious) names of the last century. Riveting, action-filled scenes alternate with meditative, exquisite evocations of the natural world, and the precarious ties that bind even the unlikeliest people together are rendered with sagacity and warmth.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

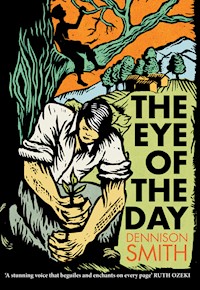

The Eye of the Day

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Periscope

An imprint of Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court, South Street

Reading RG1 4QS

www.periscopebooks.co.uk

www.facebook.com/periscopebooks

www.twitter.com/periscopebooks

www.instagram.com/periscope_books

www.pinterest.com/periscope

Copyright © Dennison Smith, 2015

The right of Dennison Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

ISBN 9781859640746

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset bySamantha Barden

Jacket design by James Nunn: www.jamesnunn.co.uk

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press:

for my father

1

Amos Cobb wrenched his boots from the trainyard mud, and the earth gave a sucking sound. Everything was slowed by the weather. The freight train full of tractors was late moving out and the commuter train hadn’t come in. Over the passengers waiting on the platform, the lamps sizzled and buzzed, while hailstones drove at a hard angle under the tin roof. The weather was nothing new: it was terrible or beautiful, and usually it was terrible when there was outdoor work to do. There was always outdoor work for Amos.

He lifted a thigh-high boot; he put it down in the muck. Doing one thing at a time kept things under control. Felling for the lumber companies and blasting in the granite pits had taught him to take his tasks slow and not let his thoughts crowd him. Otherwise, there were accidents. He was rutty and bearish and marred already, one half-finger lopped off in a sawmill, and he was only twenty-five, though to other people he didn’t seem to have an age. Vermonters said he was like a rock – strong, big and sturdy, nothing to look at – and no one had met a young rock. Now sulphur from the coal dust lined his nostrils. Soot and slush commingled on the ground. But Amos, working for the railroad tonight, wasn’t distracted by the weather.

Tomorrow he’d be up in the hills, dredging the cold lake for the float-away parts of the Shaw Browns’ dock, which had surely come apart in the storm. He could see the family, the kid and his dad, waiting on the platform for the late train from Princeton to arrive and deliver the mother. Of all his jobs, caretaking their summer cottage was the softest. Summer, even on a night like this, was a cushy season, even when he had to shovel-feed a freight train because June hail had clogged up the chute.

A stale wind blew from the coalhouse, which stood on stilts twenty feet high and spanned the length of the spur track. Climbing the ladder on a fine night, Amos would have seen the valley carrying away the Lamoille River through the quartzite foothills of the mountains and the railway tracks edging its banks. But he might not have noticed, because the scenery was always there. Vermont never changed much, which was one of its graces and the principal reason that, despite the weather, the cottagers travelled north. Vermont moved slower than the human mind, and educated people like the Shaw Browns got sick to death of their minds. Vermont didn’t change except in storms, when the mountains disappeared. When the weather passed, it changed right back again. Halfway up the coalhouse ladder, in the driving hail, he could see only the fouled yard and the freight train steaming up, and beyond it the kid and his dad, who looked grey underneath the lamps.

Amos was still like any other man, except that he was big. The kid looked up to him because he was big, but that would pass, and one day Aubrey would look down on him; it was a subtle but inevitable divide between summer and winter folk.

Amos had paused on the tenth rung. Under him was the locomotive. The hail played on the train like a toy monkey on a tin drum. Like any other man, Amos couldn’t see inside things. He couldn’t see the conductor complaining of the weather while screwing down the pop valve hard – too hard, because the gauge was busted. Or the arrow that pointed to one hundred and fifty-five pounds, though in reality the pressure had topped three hundred. He couldn’t hear the conductor mutter to himself, “If it says it, you better believe it. Give it another yank. Goddamn summers in Vermont …” Like anyone, he couldn’t see much, till under the mounting load the locomotive blew up.

The conductor died in an instant: he had his head sliced off. The train’s steel skin burst like a pickling bottle, and sheets of metal shucked like cornhusk. The firebox end of the engine rocketed into the coalhouse; the cab end disappeared. Black hail and iron, coal dust and coal chunk and disfigured steel tore across the yard, and a hundred thousand rivets shot out of the train’s iron body and into the nearby woods. One low-flying spike pierced Amos’s jaw and carried on through the back of his head; a searing darkness entered his skull, and the light in his left eye was snuffed. An awesome force threw him off the ladder to the ground, but equally strong and mysterious, the earth stood him up again.

Blast followed blast. The engine’s coal stock exploded, then the tractor oil in the freight car ignited, then the coalhouse went up in flames.

The first blast propelled Aubrey, who was slim and fragile and only eleven years old, right past his father’s arms. He landed hard on the concrete platform. A bulb shattered above him and cut him just over his eye. As he lifted himself, the second blast brought him down again. He reached out his hand to break his fall, and a glass shard sliced his thumb.

His father leaned over and said, “Your head is bleeding.” He offered a hand to help him up, but Aubrey was too distracted to see it.

“It’s not. I’m not,” he said, his heart pumping so hard it wouldn’t let him feel anything else.

His father withdrew his hand.

Aubrey pushed himself up alone. Across the tracks, the coalhouse was burning. The night was bright with fires. He tried to open his eyes wide, but the slanting rain and hail, mixed with drips of blood, stung his eyeballs. “I can’t see Amos,” he said.

“Amos?” asked his father, as if Amos were insubstantial. Everett Brown wasn’t thinking of the handyman. He was already concerned for his wife.

“He was there. On the coalhouse ladder. Is he dead?”

“I don’t know.”

“Go help him, Father.”

“You’re bleeding. And your mother –”

Everett turned round in circles like a weathercock in a cyclone. His wife had stayed behind to convalesce in Princeton and was now travelling north to join her family for the holidays. The slightest exertion could put her back in bed for weeks. He looked past the inferno towards the darker valley, expecting to see the lamps of her train twisting along the river. There they were: two dim lights gleaming in the distance. They grew brighter and bigger, then stopped and then diminished. The headlamps were pulling away. Ruth’s train had been radioed and diverted to Montreal; she would cross the border to Canada, leaving her husband and child behind.

“I’ll find us a car,” he said.

“A car?”

“To take us home. Your mother’s not coming. And this is no place …” He didn’t finish his sentence as he started to walk away.

“Don’t go,” said Aubrey.

Father called back, “Wait here.”

Aubrey leaned over the platform and spat. Soot had stuck in his throat. His tongue – he had bitten it hard – was bleeding too. He wiped his mouth and pulled his shirt sleeve, no longer white, across his forehead.

Beyond the tracks, the coalhouse, which resembled an Iroquois longhouse on stilts, was burning fast. Already the volunteer fire department had sounded the horn and a ring of villagers, wielding buckets of water, had gathered around the nearby sawmill to stop it igniting. It was too late for the coalhouse. The big log braces on the south end had given way – the fire eating quickly to the heartwood – and the house bowed on its knees. The ladder, detached from its moorings, lay blazing on the ground. Near it, something moved. Even in the jittering shadows, Amos was unmistakable.

Aubrey lowered himself onto the tracks. The heat on his face made his skin contract, and his dried eyes stung with rain. As if hell-bent on self-immolation, he ran towards the burning coalhouse. Meeting a wall of heat and light, he felt his head could break in two. He half-closed his eyes and kept running.

“Amos,” he called.

It couldn’t be anyone else. He’d risen to his feet. He was standing up. He was giant.

Amos placed a hand on Aubrey’s head to steady himself – if he’d given him his weight, he’d have crushed him. The two of them, weird in the firelight, resembled some grafted and newly made thing.

Everyone transformed in the firelight. Like a dwarfed drunk, a toddler slumped against a wall. Two ladies in wide, long dresses were pitched like tent poles, one against another. A frenzied boy called his border collie’s name, then stood pointer-like with hand to his ear, trying to hear a dog’s whine over the human crying. Down on all fours, a man groped through broken glass, feeling for his spectacles in the dark until someone led him, blind, off the platform. A policeman’s lips appeared to stretch into his megaphone as he pleaded with the panicked or stupefied people to step away from the fires.

The fire horn was audible in the hills, and farmers and doctors and veterinarians – because there weren’t enough doctors – were rushing through the weather in their one-horse buggies and Fords. From every town with a weekly paper, reporters and their cameras arrived. Headlights and lanterns stretched down the road and the parking lot overflowed. Burly farmers were rounding up the injured. Their tough wives stood on the porch of the railway hotel, waiting to wash and stitch wounds. There were people on the move everywhere now, not just train workers and passengers; the hills had emptied, the population descending into the small village of Greensboro Bend. The police chief, taking the megaphone from the junior policeman, spoke to the crowds: there were body parts to find amongst the rubble.

Aubrey stood by Amos. Beside them, the burning longhouse. Coalhouse. Aubrey struggled to remember where he was. So near the fires, his brain was lava, and the hard rain seemed to burn. Hailstones matted in his hair, then melted. He imagined hell was a railway station, but he was wrong to imagine that Amos thought so too, or that Amos was thinking anything.

“Can you speak?” asked Aubrey, who believed if someone could move it proved he was alive – that was obvious – but if he could speak, it meant he would stay alive.

As Amos nodded, he lost his balance and his hand slammed down on Aubrey’s head. The two of them stumbled but didn’t fall. Aubrey dug his feet into the mud and Amos steadied himself.

“Can you walk?” asked Aubrey.

Amos put one foot in front of the other, and they walked heavily across the yard towards the railway hotel, where the injured were gathering. Pausing on the porch, Amos leaned hard against the banister. Then he stood erect again, and, with Aubrey’s help, walked in.

Men, women and children, tribal with mud, sat on the lobby floor with their backs to the walls. Behind them, soot blackened the wainscotting. With a sewing needle and cotton thread, a large woman was pulling together the flesh of a child’s arm. A man rising from a chair left small red berries on the pale upholstery. Red tassels hung from an overhead shade, a single extant bulb not shattered by the blast aggravating the coal dust in the air. Everyone was hurt and wet and scared, but when Amos entered, people crossed themselves and looked away. They must have felt spared. Amos was huge, and the red tassels grazed his hair. The light shone down through a hole in his skull and poured out an opening in his jaw. There was a strange absence of blood.

From the outer dark, Aubrey heard his father shout, “Taxi! Taxi!” as if this were New York City. Then Father called his name: “Aubrey! I’ve got a ride!”

Aubrey, being an obedient boy, stepped away from Amos, and as he did, Amos fell. The tumult of camera bulbs, like a nightmare of morphine syringes, glassed the tiled floor.

2

Amos had worked for the Shaw Browns every summer as far back as Aubrey could remember. Each June, Aubrey’s father retreated from the marbled halls of Princeton University, and the family – father, mother, grandmother, son – took up residence in the cottage on the northern lake. Vermont was unimaginable without Amos, and that summer after the explosion passed slowly in his absence. He was only convalescing – a word Aubrey had heard repeatedly, as his mother was always sick – though the Hardwick Bulletin reported Amos had died. “Tragedy in the Trainyard” was the headline on the slushy morning in June: the conductor, the lineman and the labourer, Amos Cobb, had been killed. Then in July, on a sunny day, “Monster Defies Death.” Aubrey pasted the newspaper clippings in his photo album and read them often enough to commit the words to heart.

Over the winter in Princeton, he overheard the grown-ups talking. Greensboro neighbours, cottagers whose summer camps dotted the lakefront that had once been farmers’ fields, sent numerous appeals to his grandmother, pleading that Old Mrs Shaw decline to take Amos back into her employ. Handymen were a dime a dozen, they wrote, and the disfigured man had changed. Mrs Shaw, having read the philosophers, found no fault in their argument. Aristotle believed that an ugly man could not be truly happy, while Hume determined that ugliness was a cause of pain, not to the ugly man himself but to the innocent observer. How could Amos not have changed for the worse? her neighbours asked. Though Aubrey wasn’t consulted on the subject – being a child, no choices in his life were his – his existence bolstered their argument. The Irwins and the Smiths were concerned for their children; weren’t the Shaw Browns concerned for him? The family should take care lest their employee strangle them all in their sleep.

For a week or two in the early spring of ’39, the decision, like the spring itself, hung precariously in the balance. Also like the spring, it could not be put off indefinitely. Father, who avoided becoming embroiled in family matters, showed ambivalence, but Mother was uncharacteristically insistent, exhausting herself in Amos’s defence. Grandmother, fearful for her daughter’s health, acquiesced to her wishes. “However,” said Grandmother, “if I wake up one morning with a rope around my neck, I will hold you entirely responsible.”

Aubrey was happy, and his mother, though she was too tired to show it, seemed happy also. The family was eager to get to Vermont, where Ruth could rest. The whole family slept a good deal in Vermont. Every year, when the hibernating bears awoke, the family arrived to replace them in their sleep. Due to clean air and altitude – the lake was near the Canadian border, in one of the coldest elevations in the state – the family couldn’t keep their eyes open. Amos would have plenty of time to kill them, Aubrey said to his mother, and his mother laughed.

He thought it more likely he’d die from swimming in the frigid lake. He loved Caspian Lake, but in early summer, as the yawning trout rose from the fallow depths, the water had warmed only enough to avoid hypothermia. He knew all the warning signs of hypothermia – difficulty speaking, puffy skin, numbness and, his favourite, terminal burrowing, where the victim undressed and buried himself – and in all weather but thunderstorms, he jumped in and risked a few cold strokes. He loved Greensboro, Vermont – summer Vermont, which was the only Vermont he knew.

His mother, who understood his reckless happiness (understood it deeply, despite her illness or because of it) said her son was unshackled by the summers. His grandmother called him unruly. With schoolboy legs skinny and pale from a winter of books, he’d run whooping into the water and re-emerge blue and shivering, crying out for a towel. The maid, Delia, would bring him one. And Amos, carrying a box of tools, would walk out onto the dock to chisel the rot off the decking while the sawhorses trembled beneath him.

Aubrey sat in the back of the LaSalle sedan, wedged between his grandmother and the extravagant picnic basket. It was the first of July, and they were heading north. Though the family had taken the train up every year, this year was different. Father claimed his decision to drive had nothing to do with the previous year’s railway accident; it was only because the roads between the historic town of Bennington and the capital city had been paved over that winter. There’d been progress in the world: this was the summer of the car. It was, however, a slow, two-day journey.

Aubrey watched the land scroll past the window. He counted electricity poles or slept to make the time go faster. He read Around the World in Eighty Days and thumbed through the pictures of gemstones in The World of Rocks. When he was done, he dropped his books under his feet and ate graham crackers, one after another. His grandmother scolded him sharply. Clucking and fussing, she swept the crumbs off her travelling suit. He coughed in the air grown stewy with Father’s cigarettes, and opened the window and dangled his hand in the wind, but Mother worried that he’d lose his hand on an electricity pole. Though her voice was faint, it was full of space and tolerance, so he played with her long red hair, something he’d always done. It fell in front of him around the back of her seat. At last she looked weakly and sweetly towards him and told him she’d had enough.

Father said, “You don’t know when to stop, Aubrey. Can’t you see your mother’s tired?” He refrained from saying, “You’re getting too old for such nonsense.”

Mother never let on how tired she felt. She pulled her hair between her fingers and smoothed out the knot he’d made.

At the gas station – the smell of fuel and chewing gum pleased him – Grandmother demanded he run around the pump to expend his excess energy, commanding, “Again, young man!” until he was puffing. He wanted a piece of Bazooka bubble gum, so Mother bought it, but when her own mother complained that gum-chewing turned people into cows, she tucked it into her sleeve – the same place she kept a clean handkerchief – and whispered in his ear, “Later.”

At the overcrowded hotel where they stopped for the night, he was compelled to share a room with his grandmother, because everyone in the world, it seemed, was driving somewhere for the summer. Thankfully, there were two single beds, but his grandmother’s ancient odour – starch and talc from the faded nineteenth century – overwhelmed even the scent of stale sheets and borax. He tossed about and buried his face in the pillow. Neither of them could sleep, and as the hours passed, Grandmother sighed indignantly.

They set out before dawn. He loved the darkness in the car, and in the back seat Grandmother slept at last. Aubrey half-slept, dreamt of the lake, the loons, the tire swing over the drop-off where submarinal cliffs had been carved out by glaciers, and listened to his parent’s voices, hushed and intimate.

“What will you do first?” whispered Mother.

“Take the sailboat for a spin. You?”

“I’ll be watching.”

Mother was always watching. Whenever he read by her bedside – which he always did when she napped, though now perhaps he was too old for that – he imagined even in her sleep she was watching.

By the tedious afternoon, Aubrey was wide awake. He peered over the seat at the wooden dashboard, nagged his father to drive faster, cheered when the quick LaSalle honked at a tractor, and for the final fifty miles asked every twenty minutes, “How long till we get there?”

As if in answer to his question, and to his extreme dissatisfaction, the car stopped at a Revolutionary War memorial rising in a cow pasture, and the family set out across the field.

“My socks are wet. Can I get back in the car?” he complained, touching the edge of his shoe to the edge of a cow pie to test its stiffness.

“Aren’t you interested in history?” asked his father, already knowing the answer.

“He just wants to get to the lake,” said his mother, who was leaning against the memorial. Her lips looked pale beside the granite slab. Her skin except her cheeks was ghostly white – in all seasons, her cheeks looked sunburnt.

Grandmother was agitated. “Ruth, you should have stayed in the car. And you, young man, should appreciate artefacts like this. Your father will read the inscription.”

“Birthplace …” the professor began, but, accustomed to the acoustics of crowded lecture halls and the hollow vibration of ancient tombs, he read poorly.

Grandmother reassigned the task to Aubrey – he was staring into the distance as if the miles would shuck away and there, at the end of the pasture, he’d see the lake. “Wilson Aubrey was your namesake,” she said. “You owe it to him to read his monument.”

“Birthplace of Wilson Aubrey, Brigadier General in the Revolutionary War, who commanded the American forces in the Battle of Crooked something.”

“Crooked what?”

Aubrey squinted at the rock. He’d read The World of Rocks cover to cover. He liked rocks, in the same manner he liked the ancient ferns that grew under the porch: he liked them for their simplicity and longevity. The history of men was fleeting, but even at twelve years old, it pleased him to know the air he breathed had first become breathable two and half billion years ago. He inhaled deeply, puffed out his cheeks and held his breath and swallowed – what he called eating air.

“There’s too much moss to see it,” he said.

“Skip it and read the rest,” said Grandmother, not noticing his foolish behaviour, for she was inspecting the farmer’s fields for signs of the past.

But there was no further inscription. “That’s all,” Aubrey told her.

Though Grandmother did not have her spectacles, she glared at the memorial, insulted. “Well, it should say that General Aubrey was a great man who unfortunately had to hang his uncle for not giving horses to the cause!”

“Didn’t he like his uncle?” asked Aubrey.

“I’m sure he did.”

“How could he hang him, then?”

“It was wartime.”

“How did he know he was doing the right thing?”

His grandmother looked askance and ended the conversation. “Suffice it to say, he did what he did, and history took care of the rest.”

Old Mrs Shaw was a pragmatist. She was, as well, an atheist, which was why she liked Vermont. Vermonters did not indulge in phantasmagoria, religious obsession or romance. While across New England, Shakers had fulfilled their ecstatic mission of dancing and cabinetmaking, notably only their cabinetry had travelled north. And though Joseph Smith and Brigham Young had once milked cows in a Green Mountain pasture, when the spirit moved them they’d been led away to the salt lakes of Utah. Even the French-Canadians who emigrated south with their native Catholicism had abjured cathedral building and thrown in their lot with barn raising. Vermont was a state of red barns with weathercocks and white farmhouses with laundry frozen on the line, where the land was served before the Lord, and what had to be done was done. Old Mrs Shaw forgave the war memorial’s brevity, calling it “succinct.”

Back in the car, she complained of wet stockings and Aubrey felt vindicated. He removed his own damp shoes and socks and picked the lint off his feet. He thought about his namesake confessing to his mother that he’d killed her brother, and tried to imagine his own uncle choking in a noose. Raised to believe in the Great Man theory, in which one man was capable of changing the world, Aubrey felt uneasy about the way that great men died, their faces turned away from everything they’d conquered, as if everything they’d conquered was a lie.

He thought of the great men he knew. His father, at the top of the list because he was his father, probably didn’t belong there. People said Mother was the beauty and Father the brains, as if they were two sides of a street, while, in fact, Mother was the centre, and sometimes Father was seated in the centre with her, and sometimes he was just a fellow running around in circles, trying to find his way in. It was Amos, whom even a train couldn’t kill, who belonged at the top of the list. As to Uncle Jack, Aubrey hadn’t seen him in years. All he knew was Jack lived like a king in Mexico City and every Christmas sent a crate of pomegranates, though nobody in the family actually liked the fruit.

“Stop fidgeting,” said his grandmother. “Go back to sleep; it will make the time go faster.”

Though he wasn’t tired, he laid his head in her solid lap – there was nowhere else to put it – and looked up through the speeding window.

“My petticoats are damp,” she warned, readjusting herself beneath his head. Under her skirts she still wore petticoats, though they were hopelessly out of style.

He turned on his bed of starched cotton and stared at his mother’s auburn hair falling over the seat in front. He loved her hair, whose colour changed with the hour of the day – now horse-chestnut, now rust, now brilliant red. It was full and lush its entire length.

“Third Reich,” the car radio said.

Aubrey sat up. “Is Adolf Hitler going to take over the world?”

“Please try to sleep,” Mother said.

“You should ask your Uncle Jack,” answered Father, flicking an ash out of the window. “Of Standard Oil,” he added, and the corporation’s name sounded oily in his mouth. It was a thin mouth, though he was a handsome man. He had Romanesque features with high cheekbones, often softened by a cloud of smoke. His physique was manly enough to make up for the ivory cigarette holder held permanently between his lips. His mother-in-law would never have allowed him to smoke a hookah, so the cigarette holder substituted as a more modest reminder of evenings spent amongst Bedouins reclining on blood-coloured rugs. He’d picked up odd habits while digging in Iran and Egypt, habits he wanted to keep to himself. If the cottage walls weren’t riddled with knotholes, his son would never have known he squatted on toilet seats. Squatting was an efficient practice, and his digestion had tormented him ever since the Great War, while an American diet of steak and milk made it worse. He dreamt of an escape to foreign lands, and sometimes at dinner, in mind of the uncluttered expanses of the Mojave Desert, he forsook his fork and knife and used his fingers on the scalloped potatoes.

“Don’t talk nonsense,” Grandmother snapped at Everett. She bristled at the mention of her son in the same breath as Adolf Hitler. “And keep your eyes on the road.”

“Greta Garbo is on the lake this summer,” Father said to change the subject.

“Is it true?” Aubrey asked his grandmother, the authority on all things real.

“Bad news travels fast enough without your help, Everett Brown,” Grandmother said.

“Yes, it is true,” said Mother.

When Mother turned in her seat to look at Aubrey, he saw yellow flecks like chamomile blooms in her fair blue eyes.

“When are we going to get there?” he asked her.

“The more you ask, the longer it takes,” Grandmother answered for her.

“Is it really true Greta Garbo’s on the lake?”

“You are to leave that woman alone! No doubt she’s looking for a little happiness like the rest of us.” Grandmother pushed his head back into her lap, but between Greta Garbo, Adolf Hitler and the lake getting closer every mile, Aubrey could not sleep.

Like the Germans, he loved Greta Garbo. The Germans had fallen in love with her first, but the Americans had won her. Her rags-to-riches story was an American tale: working-class girl with a ninth-grade education rising to become the highest paid actress in Hollywood … demanding and dark, always more money, always black curtains draped behind her when the camera zoomed in for a close-up. So it wasn’t that Aubrey had something in common with Hitler that made him squirm; it was the weirdness of lying on Grandmother’s lap while remembering Mata Hari. She was seducing her lieutenant in front of a Russian icon of the Virgin Mary. The Swedish Sphinx. The vamp. She both beguiled and disdained the camera, and seemed to hold the answer to a question her audience didn’t even know to ask.

“I saw her in Mata Hari at the Bend,” he said, though Grandmother’s hand held him firmly in place.

“You didn’t,” she insisted, as if she knew everything about him.

“I did. Amos took me last June, before –”

“I knew the real Mata Hari,” Father interrupted. “I met her at a party in Paris during the war. She claimed to be a Javanese princess, but she was really just a Dutch girl who gave herself a fanciful name. It’s Javanese for the sun, literally ‘the eye of the day.’ She was a very unhappy woman.”

“Why?” asked Aubrey.

“Ours is not to reason why,” said Grandmother, who thought her grandson’s habit of always asking why was rude.

“Because she lost everything she loved,” said Father. “Her husband, children, home, even her identity.”

“It’s no wonder she became a spy,” said Grandmother.

“Actually, it’s not certain that she was a spy.”

“Everyone knows she was a spy,” said Aubrey. “She was hung for it.”

“She was shot by firing squad,” Everett corrected his son. Aubrey had no memory for history, though he was good at science and maths. “But that doesn’t make her guilty,” he continued. “She was a powerful woman, and in a horrible situation we all look for someone to blame. The Javanese believe there were cosmic reasons for her bad luck and her sadness. She always performed at night, but she named herself after the sun, and the Javanese have a myth about a child of the sun. They say, when the sun’s in the sky, the child shares all its godly qualities: he is happy, bright, energetic and giving. But when the sun goes down, the child feels like dying.”

“Oh,” Aubrey said. He didn’t particularly care about the real Mata Hari. Only Mata Hari at the movie hall in Greensboro Bend mattered: he imagined her stepping off the screen and climbing the hill to Greensboro.

“It’s a curious coincidence,” Father said, “that mata-mata means ‘spy’ in Malay. Did you know there’s no Hebrew word for ‘coincidence’?”

“Is it really true Greta Garbo’s on the lake?” asked Aubrey.

“Aubrey Brown,” Grandmother cried, “you are to leave that woman alone!”

In the unchangeable haven of Greensboro, where celebrities appeared sporadically, special rules of decorum applied. A star could hike Barr Hill, with its view of the lake and the mountain range, past picnic sites where youngsters played croquet through obstacle courses of cowpat and bramble, and the young might look up from their mallets, and the mothers and fathers from their gin and tonics and roasting corn, but no one would call out to the goddess of screen, no one chase after the salubrious Garbo; they would lift their heads like curious cows in a field and then return to grazing. Aubrey felt trapped between expectation and desire.

“How long till we get there?” he asked again.

“We’ll get there when we get there,” Grandmother answered. Disturbed that her grandson had seen Mata Hari with Amos Cobb and without her permission, she added, “You are not to go sneaking off anywhere with Amos this summer. Everything has changed. We don’t know who he is anymore. Do I make myself clear?”

Father took his eyes off the road, turned his head towards the back seat and whispered, “Aubrey … Mother … quiet … Ruth is sleeping.”

The family drove in silence.

The clock on the dash moved slowly, but time rushed past the window frame. Though the world would soon go to war again, and what had not been ploughed under by the last onslaught would shortly be ravaged by a worse one, a current dragged on the family that buoyed them nostalgically in the past. And yet in the name of progress, though the train had taken one day whereas the car took two, when the Green Mountain Flyer pulled into the station in Greensboro Bend, the Shaw Browns with their picnic basket were not on board.

Amos looked up at the clearing sky while hawks, circling on the updraft, stared down at the one-eyed giant. Though the railway had taken one of his eyes, Amos reckoned it left him the better one. Dropping his chin to his square chest, he said to the dog at his side, “More rain tonight. Don’t let the sky fool you.” The green land squelched under his hide boots, and wetness oozed through the split in the sole. Whether from snow melt or summer rain, it was always wet in the valley.

Stepping onto a grassy hummock under which lay the granite foundation of his ancestral farmhouse long subsumed by crabgrass, he looked back at his rented shack. This land had been Cobb land even before the Revolution, but after Runaway Pond it was sold away, and other than Amos there were no more Cobbs in these parts. He was lucky even to rent these days. The shack door flapped in the breeze, the lower half rotting on its hinges. A stream ran under the house and straight on through the paddock. His cow and workhorse were mud-spattered.

“What’d I tell you?” Amos asked the dog as another shower passed, a flat, grey ghost floating across the fields. “And that ain’t the end of the weather,” he said, hitching his horse to his cart.

They were on their way to the station. Amos, his horse and cart and dog were meeting the train from New York City to lug a summer’s worth of clothes and books and sporting equipment back to the Shaw Browns’ camp – up the steep hill road between Greensboro Bend and Greensboro proper, then around the lake road and down the diminishing lane. It was a shame the luggage was arriving alone – he’d always liked having the kid ride in the rig beside him while the older folks went by taxi – but he was lucky to have his job back. It was the only one he had now.

“Come on, let’s get a move on,” Amos said to the dog.

Compared to the dog Amos was a talker, but in human company he wasn’t. His jaw hurt since the accident, and he’d never been fond of chatter. He was less fond of it now than ever, as there were noises enough in his head. He lifted a boot and put it down on a maple stump smothered in mosses with a sucker tree growing out of the pulp. The dog sniffed at his big ankles and then stuck its nose in the mud.

“Go catch yourself a snake,” said Amos. So the dog chased a smell around.

Pale forget-me-nots bloomed in the mire, fed by underground streams. Black water like an oil seep in the blue flowers was all that was left of a pond. The dog returned panting, his breath making visions in the cold air. Amos turned up the dirty collar of his lumberjack jacket. In the highest reaches of Vermont, also called the Northeast Kingdom, mountains rose to the east, west and south but not to the north, so when the wind blew from the Pole, Vermonters said weather was king. Even in July, it was cold in this valley forged by a glacier, dug by a river and drowned by a pond.

“Runaway Pond. It’s a long story,” Amos said to the dog. “I ain’t gonna tell you now.”

He kicked his sodden boot against a railway sleeper, stepped over a rusted sugaring bucket and a hunk of quartzite, picked up a sharp-edged flint, imagined it might be an arrowhead, and stuffed it in his overall pocket. He could hear a car tear down Route 16. He could hear the tumult of the railway beyond the woods. His dog racing behind the horse and cart, he followed the track towards Greensboro Bend, where the roads intersected and the trains refuelled.

The Bend owed its existence to the railway. A one-horse byway in the eighteenth century, by the end of the nineteenth it had grown into a three-horse village as a sawmill emerged, then a pool hall, a school and a hardware store with a millinery shop in the rear. The Bend had continued to prosper, growing on the back of its neighbour’s success. The next stop down the line, the town of Hardwick, where granite was quarried and chiselled into graves, had boomed through the Great War, while in Greensboro, in increasing numbers since the war’s end, holiday-makers sunned themselves on the granite outcrops of Caspian Lake. The valley allowed the trains to bore through, battling the weather, snow in May, hail in June, while a cold snap frosted the radishes, and summer came, as the summer folks came, briefly. A new boarding house served travelling salesmen peddling phonographs and dioramas; a movie hall provided visions of the goddesses of screen; and the railway hotel (its couches newly upholstered since last summer) offered refreshment to the better-heeled. An ancient Model-T taxi shuttled ladies in hats and summer whites, like Old Mrs Shaw and beautiful, frail Mrs Ruth Shaw Brown, up the hills or down. The trains had ushered in the telegraph, followed by mail-order shopping and day trips to the capital city or longer adventures to real cities, Boston and Manhattan, from which cultured metropolises the summer inhabitants hailed. The wilderness had inched away to accommodate human pleasure and industry. The wolves and bears were gone. Up the hill, Caspian Lake had become a destination, and down in the valley, Greensboro Bend was the place of disembarkation.

Amos’s dog barked at a snowshoe hare whose summer-brown paw was stuck in a trap made from two tin cans. Pulling the horse to a stop, Amos said to the dog, “Dinner,” and slit the hare’s throat with a pocketknife, peeled off the skin in both directions and pulled the soft flesh from the tail. He squeezed under the ribs, then slid his hand down to the rump till out popped the entrails. He hung the carcass off a tree limb to cold-dry and heard the blast of the whistle between the hills.

When the train pulled into the Bend, Amos was there to meet it. Flags flew over farmhouse and cottage alike – the village preparing for fireworks day – and there was little evidence of the inferno the previous summer. No evidence except his own body, some half-charred trees that survived the fire and a bronze plaque on the reconstructed depot showing the names of the conductor and the lineman. A new coalhouse stood on its stilts.

Amos piled golf clubs and tennis racquets, suitcases packed with shorts and gauzy dresses and old liquor boxes heavy with books into his hay-damp rig as railway workers prepared the freight cars and passenger cars for the return journey. Cows and crates of raucous chickens were shoved on board. Tins of maple syrup and buckets of cream were loaded on the empty seats, the large steel cans rattling and clanging. And, under the din, the quiet sloshing of milk.

Amos worked with his head down so as not to look at the woman lounging on a bench amidst a circle of gin-soaked boys.

“There’s Amos,” whispered Donna, leaning on her plump hip.

“Uglier than sin,” said one of the boys.

“He don’t know nothing about sin,” she snarled. “That’s his whole problem. Too dumb.”

Her painted lips gave a false sheen to her pale skin and black hair. A gold coloured wedding ring curled around her finger like a halo around an albino snake.

“You’d know. You married him,” said the boy.

Donna Cobb glared at Amos. Though he went about his work as if he couldn’t see her, with one eye open and one stitched closed, he always seemed to be winking at her. His smooth, satiny eyelid was soft enough to line a coffin, while the rest of him was rough and veined as a lump of granite. She shuddered to think what time would do to those horrible silky scars. She forced down a wave of nausea. If only that spike had killed him; she would have looked beautiful in black.

“By what insanity did you ever marry Amos?” asked a red-haired boy with a bottle in a paper bag. He spat tobacco juiced with liquor, then casually touched her leg. “A beauty like you coulda done better. Still could.”

Donna let him finger her thigh. “Life only lasts so long anyway,” she said.

Her reasons were no one’s business. First of all, unlike any of the pawing boys on the bench, Amos never drank so much that tables and chairs got broken. He didn’t fight when he didn’t need to, or hold back when he did. He’d slugged her daddy so hard, Daddy had never come near her again. That was reason enough to marry. Even before the accident, he wasn’t exactly handsome, but he was the strongest and sturdiest man in the state. He could do the work of twenty men, and every employer knew it. His sheer size had promised to lift her out of adversity, and when she got pregnant the first time, he was gentle enough not to ask how. They might have been a happy little family, like the ones she’d seen in the movies, if, soon after their visit to the justice of the peace, the baby hadn’t dropped out dead. That wasn’t a tragedy; that was destiny. Donna had read the word a million times in the women’s weeklies. She had one, a destiny – she was sure of it.

The facts of her miserable life threatened to rise up with her breakfast. Life had broken all of its promises. Amos was a monster, or he looked like one, which was tantamount to being one, and either no one wanted to hire him or he didn’t want to work for them. The exception being one stuck-up family: the Browns, the Shaws, the Shaw Browns, whatever they were called. The village had pooled some money together to see the two of them through his convalescence, but that was long spent. This winter, increasingly broke, they’d moved from a half-decent rental on Main Street to a shack in a dried-out swamp, where Amos said he felt he belonged. He rightly belonged in the grave. His strength had come back tenfold, but what did he do with it? Nothing except rise up like a zombie in their bed and fill her with his seed. Her belly was getting bigger again, and now in the mornings she couldn’t keep down her food. Hoping the condition wouldn’t stick, she’d told him she was getting fat on cheap lard because he couldn’t afford butter – and this in a land of cows! She hated even to lay eyes on him, but she wasn’t going to let him ignore her.

“Hey, Amos!” she called across to him. “Looks like the Browns got you hard at work. Where are they?”

“Driving up this year,” Amos called over his shoulder, still not looking. She was drinking and flirting again.

“I want a car!” she purred to the boys. “Which of you men wants to buy me a car?”

“My grandpa says girls shouldn’t drive cars,” said one.

“That’s ’cause he’s old and dotty!” said Donna. “Don’t he know girls drive in the movies all the time? You know Greta Garbo’s summering on the lake? I saw her in the flesh, right here in the station. She had the nattiest luggage. The postmaster says she calls herself Harriet Brown.” She screamed across to the hay rig, “Wonder what the Browns think of that, hey, Amos?”

Donna took a swig from the red-haired boy’s paper bag and said, “I bet Greta Garbo can drive a car.”

Now the coal chute opened and drowned out the racket of the animals shipping south to slaughter and the iron-toothed raving of the sawmill across the road.

“My pa sold her some milk,” said one boy. “Said she was thin as a deer in winter.”

“Which of you thinks I look like a dark Mae West? Tell me, don’t I look just like a really dark Mae West?”

The fellows on the platform looked Donna up and down and right through her dirty dress. She’d played Annabelle West in a performance of The Cat and the Canary before she dropped out of school to tend to her drunken dad. She did look a little like the film star. But though she was pretty and easy, everyone knew she was crazy, widely cracked, like two legs. The boys grinned at Donna, because a guy can enjoy crazy when he gets it for fifteen minutes and isn’t the one stuck with it for life.