7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

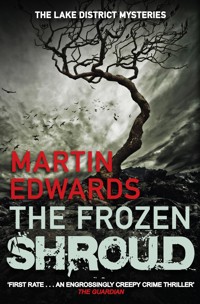

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Lake District Cold-Case Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Death has come twice to Ravenbank, a remote community in England's Lake District, each time on Hallowe'en. In 1914, a young woman's corpse was found, with a makeshift shroud frozen to her battered face. Her ghost - the Faceless Woman - is said to walk through Ravenbank on Hallowe'en. Five years ago, another woman was murdered, and again her face was covered to hide her injuries. Daniel Kind becomes fascinated by the old cases, and wonders whether the obvious suspects really did commit the crimes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 441

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

The Frozen Shroud

MARTIN EDWARDS

Dedicated to my cousins Mark, Barbara, Heather and Nigel, and to the memory of Mona, who died while I was writing this book

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

FIVE YEARS AGO

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

NOW

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

About the Author

By Martin Edwards

Copyright

FIVE YEARS AGO

CHAPTER ONE

‘Do you believe in ghosts?’ Miriam asked.

Shenagh Moss stretched in the ancient armchair. Oz Knight had once said her every movement possessed a feline grace. Shenagh had moved on – gracefully, of course – from Oz, but he wasn’t wrong. Where she came from, nobody cared about elegance, but these days, poise came as naturally as breathing. Even with no admiring man around, just an elderly housekeeper with anxious eyes.

‘Ghosts are about the past. Look forward, not back, that’s my philosophy.’

Miriam frowned at a mud-stain disfiguring the carpet she’d cleaned for so many years. Thinking about her long-dead husband? Poor, stuck-in-a-rut Miriam. Sixty was no age, but to look at her you’d think she had one foot in the grave. At least she’d made the effort to dye her hair, but why that dismal shade of mousy brown? Her beige cardigan, shapeless grey skirt and thick stockings were a perfect match for this room, with its faded furnishings, and faint aroma of mothballs.

Yet it was never too late to change your life. Look at Francis, twelve years older than Miriam, and a martyr to osteoarthritis. From the moment they met, Shenagh knew she could put a smile back on his face. Life was short, got to grab your pleasure when you saw the chance.

‘We can’t ignore the past.’ Miriam rested a hand on Shenagh’s shoulder, gripping bone through thin silk. ‘Remember the Faceless Woman.’

‘Our very own ghost?’ Shenagh giggled. Forget the rotten weather, life was good. She wanted to cheer Miriam up. ‘Hey, after haunting Ravenbank all those years, you’d think she’d get bored. Forever prowling up and down the same lane, where’s the fun in that?’

‘You may laugh, pet, but Mrs Palladino once caught sight of the Faceless Woman. Gave her the shock of her life – and she wasn’t given to flights of fancy.’

Shenagh glanced at the framed photograph on the sideboard. With her long nose, pursed lips and pointed chin, the late Esme Palladino looked as though she disapproved of imagination, and anything else smacking of self-indulgence. You’d never guess she’d drunk herself to death.

‘Spooky!’ Shenagh pretended to shiver. ‘Makes you wonder why she carried on living in Ravenbank.’

‘Why ever not? This is the loveliest spot in the Lakes – ghost and all!’ Miriam brightened. ‘You could be so happy, pet, living here permanently. This is your home.’

‘Thanks. You’re very kind.’

Yet Miriam was also wrong. Home for Shenagh should be Katoomba, high above her native Sydney in the Blue Mountains. Or maybe a big house at Double Bay or Vaucluse, with views of the harbour. Not a decaying mausoleum on the edge of Ullswater. She wasn’t nostalgic for Sydney’s outer western suburbs, of course. No one could be sorry to leave behind that weatherboard hovel by the train track in Jannali. But she needed room to breathe. Ravenbank was suffocating her.

‘Well, you’re one of us now.’

There was no higher praise that Miriam could bestow. Shenagh was the daughter she’d never had, according to Francis. And for sure, she’d have been a massive improvement on Shenagh’s actual Mom, a surfie chick who gave birth at fifteen, and was run over by a truck one night when she was out of it on cocaine, looking for business on the streets of Caringbah instead of looking after her daughter.

‘You’re very kind.’

‘You’re not fretting about that dreadful man Meek, are you, pet?’

Miriam cared, that was the difference. She’d never even met Craig Meek, but already she was worried sick about what he might do, now he was out of prison.

‘Hey, it’s fine. Craig isn’t any sort of ghost. Just a selfish, troublemaking bully. Nice as pie as long as everything is going his way, but when it isn’t …’

Miriam peered at her, as if straining to decipher a message written in code. ‘Promise you’ll be careful. Now he’s back in Pooley Bridge … well, it’s too close for comfort, when he has a history of violence.’

‘I’m not running scared,’ Shenagh said. ‘I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction. And that is a promise.’

The velvet curtains weren’t thick enough to deaden the lash of rain on the flagstones outside. The clock struck six, but it felt like midnight. This vast sitting room was draughty, despite the crackling fire. Shenagh reckoned the whole house needed a makeover to bring it into the twenty-first century, but she wasn’t going to hang around, waiting for it to happen. Who could blame her for counting the days until she landed back at Kingsford Smith?

Miriam tossed another log from the wicker basket onto the flames, and Shenagh reached out to warm her hands.

‘Why do you ask about ghosts?’

‘Don’t say you’ve forgotten? Today is Hallowe’en.’

‘I wanted to go to a party.’ Shenagh feigned a pout. ‘Francis wouldn’t hear of it. I told him, you don’t have to believe in ghoulies, it’s only an excuse for a piss-up. But he’d rather stay at home, the lazy sod.’

‘One thing he isn’t, pet, is lazy.’ Miriam seldom ventured to contradict Shenagh, but she’d defend Francis to the death. ‘He’s absolutely tireless. That’s why he reached the top of his profession.’

‘Yeah, I hear the nurses worshipped him. No wonder he expects everyone to jump when he says jump. Sometimes he makes me feel like a stupid kid.’

Shenagh smiled. Both of them knew she was anything but stupid. Francis wouldn’t want to spend the rest of his life with an airhead, whatever she looked like.

‘It’s just his way.’

‘He thinks the world of you, and no wonder. During that terrible time, when Esme was ill, he couldn’t have got through it without you.’

A pink tinge appeared on Miriam’s leathery cheeks. This was another of Shenagh’s gifts, her lavishness with praise. It cost nothing to make people feel good, and sometimes they were generous in return.

‘You always say such nice things, pet, but I was only doing my job.’

‘Francis shouldn’t have stayed on in this house,’ Shenagh said. ‘Even though he doesn’t believe in ghosts any more than I do.’

‘Mr Palladino’s a man of science.’ Miriam shook her head. ‘He doesn’t believe in anything he can’t see and touch.’

Shenagh clapped her hands. ‘How’s this for an idea? We can celebrate! Commemorate the occasion. I mean, we can’t just ignore our very own legend. It wouldn’t be fair on poor old Gertrude. Let’s mark the Faceless Woman’s anniversary with champagne!’

‘Oh, pet, I don’t think it’s …’

The sitting room door creaked open, and the words died on Miriam’s tongue. The man who walked in carried a stick, and winced with every step he took. His sparse grey hair was wet, his Barbour coat dripped onto the carpet.

‘Filthy night.’

A voice of authority, unaccustomed to dissent. How he must have relished making the nurses swoon. He claimed he missed the world of medicine, but Shenagh suspected he missed not the patients, but the power. Even she’d been startled by his reminiscences of life and death in hospital, and a God-playing former colleague known as Morphine Morris: ‘No bed-blockers in his wards, I can tell you, not after one quick squirt of his trusty syringe!’

‘Dreadful, isn’t it?’ Miriam said.

No wonder Francis had kept Miriam on after Esme’s liver finally gave up the unequal struggle. Miriam served the same purpose as the adoring nurses. Yes, Mr Palladino, no, Mr Palladino, three bags full, Mr Palladino. And it wasn’t only Francis; her son was someone else she spoilt rotten. No doubt it was the same with her husband, the late lamented Bobby. Big mistake. Let a man get his own way, and he’d walk all over you.

‘Is your back hurting? Your own silly fault, Frankie. I warned you not to overdo it.’

Her easy familiarity shocked Miriam, adding to the fun. The older woman helped Francis remove his coat, and hurried off to hang it up in the hall. He hobbled over to Shenagh’s chair, and bent to brush his lips against her hair.

‘Why are you keeping Miriam here?’ he murmured. ‘There’s a storm brewing. She needs to get back home.’

‘We were talking about the Faceless Woman.’ She kissed his cold cheek. ‘It’s my first Hallowe’en in Ravenbank, and I’ve paid no attention to the story about Gertrude Smith till now.’

Francis Palladino made the sort of scornful noise he usually reserved for people campaigning for more wind turbines in the Lake District. ‘You don’t want to bother, it’s a load of tosh.’

‘Miriam didn’t want to go until she was sure you were safe and sound.’

‘I’m not a bloody invalid.’

She ran her fingertips along his tweed-clad thigh. ‘You’ll be sacking your masseuse, then?’

‘Somehow,’ he murmured, ‘I don’t think so.’

As Miriam bustled back into the room, he said, ‘So you and Shenagh have been discussing our little legend?’

‘Well, it is Hallowe’en, Mr Palladino,’ Miriam said.

‘Spook night!’ Shenagh cried. ‘You know, I really ought to check out this Faceless Woman. Will I find her with a Google search? Does she have a Facebook page in her memory? Or is that a contradiction in terms, given the – uh – face shortage?’

‘It’s no joking matter, pet!’ Miriam’s eyes widened. ‘Gertrude Smith was murdered on Hallowe’en, and the person who killed her wasn’t hanged. That’s why her spirit is tormented. Justice was never done.’

Outside the house, someone hammered on the old oak front door. Miriam jumped at the very moment that Shenagh dissolved into a fit of helpless laughter.

‘You gave me the fright of my life.’ Miriam was only pretending to scold her son. In her eyes, Robin could do no wrong. ‘We were talking about the Faceless Woman.’

‘Sorry to make such a racket.’ Robin Park chortled, not looking sorry at all. ‘The doorbell needs fixing. Want me to sort it out when I get a moment, Francis? I was telling Shenagh the other day, if the gigs ever dry up, I’d make a pretty decent handyman.’

Palladino’s reply was a non-committal grunt. Robin never would get a moment. The offer was for his mother’s benefit, one more thread in the tapestry she’d woven, depicting Robin the Virtuous, a man kind and generous to a fault. Shenagh thought him lazy and self-obsessed, but she’d met fellers a hundred times worse. He was good-looking, good company, and a pretty good jazz pianist. She’d have been tempted, definitely tempted, but at the cocktail party where Oz Knight introduced them, she also met Francis. And Francis might not be a lean hunk with startling blue eyes, but he was a civilised and childless old-school Englishman who owned a mansion. No contest.

Robin grinned. ‘Gertrude Smith, eh? She’s part of Ravenbank’s heritage. Like Mum, really.’

His mother frowned. ‘It’s no joke, dear. What happened to that wretched young woman was pure wickedness. It makes my stomach heave just to think of it.’

‘Take it easy,’ Shenagh said. ‘It was a long time ago.’

‘Gertrude Smith never could rest in peace.’ Miriam swallowed hard. ‘On dark nights in the cottage, when Robin is away, I can’t help thinking about that poor young creature, walking down Ravenbank Lane, without a face.’

Robin put his arm around her bulky shoulders. ‘Not to worry. Nobody left alive has ever seen her ghost.’

‘What exactly happened to Gertrude?’ Shenagh asked.

Miriam cleared her throat. ‘Someone battered her face with a heavy stone, and kept on until all that was left was a bloody pulp. No eyes, no nose, just a mashed-up mess.’

Francis frowned, and opened his mouth to speak, but there was no stopping Miriam in full flow.

‘And that’s not all. Gertrude’s face was covered with a woollen blanket, like a shroud. The men who found her had to rip it off. The cold had frozen the shroud to her flesh.’

CHAPTER TWO

‘You don’t suppose Miriam was frightened of being attacked as she walked home?’ Shenagh asked, an hour later. ‘Is that why Robin came, to keep her company?’

‘Miriam is perfectly capable of looking after herself, on Hallowe’en or any other day. Besides, who would want to murder her?’

‘Oh, I dunno. A homicidal ghost, thirsting for vengeance because of the wrong done to her?’

Breathing hard, Palladino shifted his position in the bed. The sudden movement of his crumbling joints caused a spasm of pain to cross his face. ‘Miriam doesn’t have an enemy in the world. She deserved better than a good-for-nothing husband, let alone that idle lad of hers. Calls himself a musician, but does nothing except take advantage of her good nature.’

In fact, the idle lad was thirty-plus, and Francis’s distaste stemmed from the way Shenagh let him flirt with her. Not that either she or Robin meant anything by it. He wasn’t into commitment, frustrating Miriam’s dream of surrounding herself with grandchildren she could spoil. The old lady had even tried a bit of unsubtle matchmaking between the pair of them. But although Miriam would be the ideal mother-in-law, she was wasting her time. As far as Shenagh was concerned, Robin’s role in her life was to divert attention from her latest bit of fun. Like Mom, she’d never been a fan of monogamy. Francis didn’t have a clue about what she was up to, thank God. Anyway, it was harmless enough. No way would this latest dalliance interfere with her plans for the future.

She nibbled Francis’s dry lips. He was such a well-dressed man that it always came as a shock when he shed his clothes to reveal this scrawny body. His flesh felt like pudding pie, and the wonky vertebrae cramped his style as a lover. Massage helped, but it couldn’t make him young again. Not that she was complaining. Long ago, she’d learnt you can’t have everything, though it didn’t stop her trying.

Over his shoulder, she stuck her tongue out at a photograph in an ornate ironwork frame standing on the bedside cabinet. Esme, again. In this black-and-white, head-and-shoulders portrait, she was in her thirties, hair in a bun, wearing her irritable schoolmarm face. The mirthless smile betrayed impatience, as if she wanted to scold the photographer for being so slow to take the picture. It amused Shenagh that Esme was gazing at her, in bed with her husband. Sort of a turn-on, having a dead wife as a voyeur.

‘Miriam won’t come to any harm.’

‘Hope not. She’s petrified of ghosts.’

‘So was Esme. But only when she was four sheets to the wind. Claimed she saw Gertrude Smith at Ravenbank Corner one Hallowe’en, and managed to convince Miriam it wasn’t a hallucination. She’s extraordinarily credulous, for such a tough old boot.’

The tough old boot was younger and fitter than Francis, but Shenagh kept her mouth zipped. She’d learnt not to tease him about his age.

Her hand sneaked between his legs, but when he didn’t respond, she murmured, ‘Hey, it’s Hallowe’en. A night when all sorts may happen.’

‘A feeble excuse for shops making money, and children making a nuisance of themselves.’ He’d lapsed into grumpy old man mode. ‘I blame the Americans. Thank God we don’t have trick-or-treating in an out of the way place like this.’

‘I’m still glad Robin walked Miriam back to her cottage, made sure she’s all right. She’d have a seizure if she caught a glimpse of the Faceless Woman.’

‘Superstitious claptrap, that’s the top and bottom of it.’

Sure was, but Francis needed contradicting, every now and then. If he couldn’t handle contrariness, he should’ve signed up for the senior citizens’ tea dance down the road in Penrith, not started shagging a red-headed westie from Penrith Valley on the other side of the world.

‘Several people have seen Gertrude’s ghost over the years. Jeffrey Burgoyne told me so.’

‘When were you talking to Jeffrey Burgoyne?’

He sounded disgruntled, but surely not even Francis could be jealous of Jeffrey? ‘Must have been back when we first met. He asked if I knew about the legend.’

Francis snorted. ‘Pay no attention to Jeffrey. Fellow’s an actor, spends too much of his time prancing around like a poor man’s Ian McKellen. And he’s a dreadful gossip.’

Was there a touch of homophobia there? Probably, but Shenagh didn’t intend to make an issue of it. She knew something about Jeffrey that Francis would never guess, but she wasn’t in the mood for gossip. The last thing she wanted was to start a conversation about Jeffrey Burgoyne and his partner.

‘Sweetheart, this is Ravenbank. What else is there for people to do? That’s why I want to escape.’

He squeezed her right breast. Hooray! His fingers were cold, but at least there was life in the old dog yet.

‘Can’t wait,’ he said in a throaty whisper.

The eight-day mahogany mantle clock was an heirloom. A wedding present to Francis Palladino’s great-grandfather, with floral decorations and brass bun feet, and topped by a gilded cockerel perched on two books. Shenagh loathed its extravagant ugliness.

The clock struck each hour on a gong; at one in the morning, it woke him. They’d shared a couple of bottles of claret over dinner; Shenagh had waved away Miriam’s offer to do the cooking, and Francis found that fine wine always helped compensate for his lover’s lack of culinary expertise. The combination of the alcohol, the fire, and their exertions in bed had made him drowsy, so he hadn’t accompanied her when she said she would take Hippo for a walk.

‘With any luck, I’ll come face to face with Gertrude’s ghost.’ She giggled. ‘Hey, I guess that’s a contradiction in terms if the ghost doesn’t actually have a …’

‘Don’t stay out too long,’ he muttered. Within five minutes, he was snoring.

One o’clock? She must be back by now. After locking up, she’d gone straight up to bed. Might she be waiting to offer him her own special version of trick or treat? He levered his protesting body out of his armchair, switched off the light, and stumbled upstairs.

The bedroom was empty. No sign of her in the bathroom, either.

‘Shenagh?’

He called her name twice more. She didn’t answer.

Puffing and grunting, he made his way back down the steep staircase. Hippo’s basket was empty. Surely Shenagh hadn’t had an accident while taking him out? She was young, fit, and fearless. Yet a lifetime in medicine had taught him that nobody was invulnerable. Disaster often struck out of a clear blue sky. Or out of a dark, starless sky.

What could have gone wrong? Hippo – properly, Hippocrates – was an Irish Setter, five years old and full of energy. Too boisterous for his owner’s taste, but he had been a present for Esme after she fell ill, and after her death, Miriam, ever the sentimentalist, begged him not to let the dog go.

Shenagh loved Hippo too, a case of one tactile extrovert bonding with another. She used to say she enjoyed nothing better than being licked by a wild, panting animal. When, in the damp of autumn, Francis’s arthritic back started playing up, she’d volunteered to take Hippo for walks by herself. Ravenbank was an ideal place for a dog to roam, whether on the muddy track by the lake shore, or along the secluded lanes and overgrown pathways criss-crossing between the scattered houses.

No choice but to go and look for her. Shuddering with dismay, he pulled on his Barbour coat and thickest lambswool scarf, and shoved his age-spotted hands into leather gloves. Before grabbing his torch, he donned the garish woollen hat Shenagh had bought as a birthday present. He’d avoided wearing it until now, because it made him look foolish; at least nobody else would be out there to see it.

He knew better than to panic. Thirty-five years as a stroke physician had accustomed him to distress. From student days, he’d cultivated a cool fatalism. Speculation was the enemy of medicine. Doctors traded in facts, unlike patients who made themselves sick and unhappy by allowing their thoughts to roam. Imagination ranked with superstition and religion. A rational man could have no time for any of them.

The moment he stepped outside, the cold sank its teeth into his cheeks. Ravenbank was a small and isolated peninsula jutting out into Ullswater, at the mercy of gales roaring down from Helvellyn. The rain had slackened to a malicious drizzle, but swirls of fog kept blowing in from the lake, and the wind howled through the trees like a creature in pain.

He headed for the path to the ruined boathouse. To his left lay the grave of the woman who had once lived here. The jealous wife who had battered Gertrude Smith to death. This part of the estate had become a wilderness, the old lichen-covered tombstone invisible beneath a tangle of dripping ferns, serpentine brambles, and stinging nettles. What had possessed Clifford Hodgkinson to bury the rotting remains of his disgraced spouse in the grounds of the Hall? Morbid sentimentality, that was the top and bottom of it.

‘Shenagh!’ he called.

No answer. What the hell was she playing at? Once or twice he’d wondered about her new-found enthusiasm for taking Hippo for a walk late at night. It wasn’t the form of exercise she usually favoured. Francis had warned her to be careful. Craig Meek knew where she lived, and a crude thug like that was capable of anything. But Shenagh was stubborn, and insisted she’d never let Meek mess her about again. She refused to become a prisoner in her own home through fear of anything he might try to do.

Once or twice, Francis had asked himself if walking the dog was a subterfuge, an excuse for getting out of the house so that she could meet someone in secret. Namely, that conceited lecher, Oz Knight. But he’d dismissed the idea out of hand. Knight was history as far as Shenagh was concerned; besides, he’d never be able to explain any nocturnal absences to that wife of his. Francis knew better than to give in to paranoia. Shenagh was a lovely woman, and any red-blooded male was bound to lust after her, but she knew which side her bread was buttered on. He was confident of that.

The worst case scenario was that Shenagh or Hippo had finished up in the water. He’d start by eliminating this possibility; a reassuringly scientific approach. Shenagh was sure-footed, and a strong swimmer. Her early years had been tough; he’d never pried into details, but she’d developed an instinct for self-preservation. Much as she cared for the dog, if it got into difficulties, she’d not risk her life on a rescue. The lake was deep and excruciatingly cold. Nobody could survive its icy embrace for long.

Rain spat in his face as he limped along the muddy track. On the far side of Ullswater, lights glimmered behind curtained windows as Hallowe’en parties staggered to an end. Headlamps flickered as vehicles on the main road to Glenridding passed between the trees on the west bank. The east side of the lake was silent but for the melancholy hooting of an owl, and the muffled scrabbling of an invisible fox. His torch beam picked out the way ahead. The rest was blackness.

The air smelt of damp leaves and wet earth. The lakeside path was bumpy, and he needed to watch where he put his feet. It didn’t help that the gale was making his eyes water, and his vision was blurred. How easy to trip over a tree root, and snap his Achilles, especially when he was hampered by this damnable pain in his back and knees. Gritting his teeth, he followed the path’s curve around the promontory. No sign of Shenagh or Hippo.

Reaching a gap in the mass of trees, he began to climb towards the heart of Ravenbank. The downpour had made the ground treacherous, and his boots kept sliding as he struggled up the slope, but he pressed on. He knew this place like the back of his hand, and since Esme’s death he’d found comfort in the familiar, yet Shenagh was right. He was too set in his ways. If he didn’t change them now, he never would. She had opened his eyes to fresh horizons that he was desperate to explore, before it was too late.

Where the hell was she?

His boots pinched, and he could feel blisters forming on his heels. The wind blew a thin, spiky branch into his face, almost taking out his eyes. He brushed it out of his face, and carried on until he reached the spot where a stony lane petered out into a rough track.

‘Hippo! Hippocrates!’ He whistled twice before he called again. ‘Are you there, boy? Shenagh, where have you got to?’

The fog clutched at his throat as he approached the Corner House. Wheezing noisily, he stopped to rest his aching back against the For Sale sign. In case Shenagh had taken shelter inside the empty cottage, he peered through the cobwebbed windows, but saw nothing. Taking a deep, rasping breath, he limped on down Water Lane. His torch beam picked out Watendlath, the whitewashed home of that pansy Jeffrey Burgoyne and his boyfriend. Francis didn’t care for the boyfriend, or the way he looked at Shenagh when he thought nobody else could see. Was he wondering what it would be like with a woman? People nowadays hadn’t the faintest idea of how to behave.

A tall hawthorn hedge marked the boundary of the Hall’s grounds. He decided to retrace his steps, and follow one of the paths that led through the wooded area. Near to the beck, not far from where the two lanes crossed at Ravenbank Corner, Gertrude Smith’s corpse had been discovered. And this was where Esme insisted she’d seen Gertrude’s ghost, a shimmering white phantom with a bloodied, unrecognisable face.

Absolute bunkum. Esme had downed too much gin while he was at the hospital, that long ago Hallowe’en.

‘Hippo!’

At last his patience was rewarded. His tired eyes detected a movement in the distance, moments before a familiar bark ripped apart the silence of the night. Within seconds his torch fastened on the big, awkward dog, bounding towards him. Relief washed through him as he bent down, and patted Hippo. The fur was sodden.

‘So what have you done with Shenagh, old fellow?’

Hippo whimpered.

‘Is she hurt? Don’t tell me she’s taken a tumble, and fractured her ankle?’

The dog pulled away from him, and loped over the grass towards a clump of silver birch trees. Francis hurried after him, stumbling in his efforts to keep up. Somehow he managed not to lose his balance, but his heart was thudding and the throbbing of his back made every movement a test of will.

Suddenly, the narrow beam of light from his torch caught a huddled shape on the ground.

He’d found Shenagh.

‘For God’s sake, what has he done to you?’

He’d forgotten that he didn’t believe in God.

Hippo stood panting over the motionless form. It took Francis an age to catch up, but he recognised Shenagh’s black anorak, jeans and boots. They were designer cowboy boots; he’d bought them for her birthday, stifling his horror at the ridiculous price.

As he drew closer, his torch beam moved up towards her neck and face. They were covered by a rough woollen blanket. He pulled it away and hurled it onto the sodden ground.

Shenagh had lost her face. The lovely face he had so often kissed.

As he stared at the bloody, ruined features, he let out a howl of rage and pain. A fearful noise, the cry of a beast with a mortal wound.

NOW

CHAPTER THREE

‘Murder for pleasure was invented by a man who lived down the road from here,’ Daniel Kind told his audience. ‘Thomas De Quincey moved into Dove Cottage a year after the Wordsworths left for Allan Bank. You can understand why the tourist board highlights the poetic daffodil fancier. Better PR than a self-confessed opium eater obsessed by serial murder.’

Laughter drowned the rain drumming on the skylights of the lecture theatre. Two hundred and fifty paying customers had come to Grasmere for a Saturday conference on Literary Lakeland. Daniel had turned down countless speaking invitations since quitting academe and starting a new life in the Lake District. In Oxford, he’d lost his zest for lecturing, but the sea of faces in front of him gave him that old adrenaline rush.

‘De Quincey wasn’t a monster, any more than people who enjoy a good murder – any more than Mr Wopsle in Great Expectations, or people flocking to watch The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, are monsters. The world in general is, De Quincey said, bloody-minded. “All they want from murder is a copious effusion of blood … but the enlightened connoisseur is more refined in his taste.” De Quincey was no different from me or you. We all like a good murder.’

He always made eye contact with his audience, and now his gaze was drawn to a woman in the front row. Wherever she’d sat, you couldn’t miss her. Not among the grey hair and cardigans, and not only because she was olive-skinned, not white. Glossy black hair, black eyes, high cheekbones. Her lipstick and nails were crimson, the silk blouse dazzling yellow. A tablet computer rested on her lap, but her tiny hands were motionless.

‘He was an eccentric, De Quincey, a mishmash of contradictions. A solitary soul who fathered eight children. A satirist with a morbid cast of mind. An addict who was also a notable journalist – though come to think of it, that might not be such a contradiction after all.’

The woman tapped into her tablet. Oops. For all Daniel knew, she worked for the Westmorland Gazette, whose long ago editor was – Thomas De Quincey.

‘I’m not saying De Quincey lacked sympathy for victims of crime. He points out that Duncan’s graciousness, his unoffending nature, makes his murder in Macbeth all the more appalling. But what fired the man’s imagination was the nature of murder. Macbeth, and Lady Macbeth, intrigued him more than their victim. He was the first writer to focus on a burning question. A question that has fascinated people ever since.’

Daniel paused. The woman leant forward, lips slightly parted. Their eyes met.

‘The fundamental question about the ultimate crime. The question that haunts us all. Just what is it that drives someone to kill?’

As Daniel inscribed a hardback for the last woman in the queue, he spotted through the crowd the leonine hairstyle of Oz Knight. Tall, tanned and trim, he was making for the authors’ table. That hair was unmissable – waves so sweeping you could almost surf them. He wore a hand-tailored black jacket – Charvet, at a guess – and a white shirt, unbuttoned to the waist. For a man close to fifty, his physique was enviable, and he relished giving people a chance to envy it.

‘A fabulous lecture, and an even more fabulous book! Treasure that personalised copy, madam, it’s one for the pension fund!’

Oz’s voice was melodious, if unnecessarily loud. A touch of humorous self-parody made his egotism almost tolerable. Yet it was lost on the woman, a slim redhead who was obviously no fan of chest hair. She rolled her eyes, and hurried off in search of refreshments.

‘Great audience today,’ Daniel said.

‘Sold every ticket months in advance!’ Oz gave a theatrical bow. Over-the-top dandyism was part of the package he’d constructed to create a high-profile business, the events management company which had organised this conference. A past master of the technique of persuasion, he was charming and persistent enough to tempt even Daniel to be a speaker. ‘But it’s not simply about putting bums on seats. It’s about creating a buzz, and a wonderful experience for everyone here. To miss the chance of talking about De Quincey in the village where he made his home would be – simply criminal.’

Daniel had woken up wishing he’d never agreed to take part. The conference had seemed like a good idea at the time – but why return to a past he’d escaped? Yet he’d enjoyed the day, and the audience’s enthusiasm gave him a buzz. Now he wanted to unwind.

‘It was fun.’

‘Now, it just so happens that one of my clients is recruiting speakers for a month-long luxury cruise. Sail from Southampton to the Caribbean, the itinerary is incredible. Money no object for the right lecturers, and invitations are only going to Europe’s leading—’

Daniel held up his hand. ‘Stop right there! I’ve not been bitten by the bug all over again, you know. Today’s a one-off. When I quit the television series, I decided—’

‘Of course. I understand. You moved to the Lakes for a reason. Forgive me, I should never have mentioned it.’ A smile flashed, vivid as lightning. ‘You won’t blame me for trying, I hope?’

‘No problem.’

‘I’ll leave you to head back for the green room and a well-deserved break. I must find my wife. We need to schmooze the sponsors.’ Oz clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Forget what I said about the cruise, it was crass of me. A colossal opportunity, incredible exposure, and an itinerary to die for, but you don’t want to spend your life back on the treadmill, do you? The global speaker circuit. You have other fish to fry. Fame and money aren’t everything, you’re absolutely right. Catch you later, eh?’

Oz waltzed off, leaving Daniel – probably like most people he talked to – feeling his head had been pummelled. He doubted he’d heard the last of this cruise; it felt more like the opening skirmish in a campaign destined to become a battle of wills. Was this what it was like to fall prey to an accomplished seducer? Oz was legendary for his conquests, in his private life even more than in business; Daniel had asked around, after Oz made his original approach, and persisted after being turned down flat. The gossip was that he’d run wild until, at forty, he’d tied the knot with a girl who worked for his company. Not that marriage had cramped his style.

Money, Daniel presumed, made up for a lot, along with the mansion on Ullswater and holiday homes in Mykonos and Zermatt. One other thing he’d learnt was that Oz stood, not for Oswald, or even Osbert, but for Ozymandias. For God’s sake, what sort of parents would do that to a child? No wonder he had a healthy self-image, he’d have needed it to cope with the mockery at school.

He watched Oz greet the olive-skinned woman from the front row. They embraced, and Daniel noticed the woman’s wedding ring. So that was Melody Knight. As she held forth, Oz listened without a word. The king of kings had transformed into a dutiful husband.

Daniel squeezed into a seat where he could listen to the last presentation of the day. The speaker was Jeffrey Burgoyne, his topic the supernatural stories of Hugh Walpole. In the green room, Jeffrey had proposed a quick drink at the end of the day. He described himself as a jobbing actor, part of a two-man theatre company, and lived in Ravenbank, like Oz and Melody Knight.

Jeffrey didn’t stand at the lectern, or bother with notes. He strode up to the edge of the platform, determined to hold the audience in the palm of his hand. Overweight and red-faced, he looked more like a gentleman farmer than the Lake District’s answer to Kenneth Branagh. But he had presence.

‘When I listened to Daniel talking about Thomas De Quincey,’ he said, ‘I was reminded in a strange way of Hugh Walpole. Once the poor devil was a household name, now he’s forgotten. If people think of him at all, they pigeonhole him as a writer of sugary Lakeland sagas. Look beyond the Herries Chronicles, and you see a man who led a weird life, and wrote even weirder stories. If you fancy a masterpiece of the macabre, read Walpole’s last novel. A landmark in psychological suspense, yet few people know it. It was only published after he died, and it’s called … The Killer and the Slain.’

You could tell Burgoyne was an actor. This wasn’t so much a talk as a performance. Daniel saw Melody Knight note the book’s title.

‘As with De Quincey, the contradictions are mesmerising. Walpole lived in Brackenburn, his “little paradise on Cat Bells”. He designed his own lovely terraced garden, and was a generous host to everyone from J.B. Priestley to Arthur Ransome. He had the gift of friendship. Sadly, he also had a fatal flaw. He wanted everybody to love him.’

Jeffrey cleared his throat. ‘There was a dark side to Walpole. Something deeply unhappy about … the way he felt the need to keep so many secrets. When he proposed to a girl, he was heartily relieved when she turned him down. Even after his death, his biographer was tediously discreet. All he said was that Walpole found visits to Turkish Baths provided “informal opportunities for meeting interesting strangers”. But his stories give us clues to the terrors that came to him at night. He was obsessed with ghosts.’

The supernatural sparked Walpole’s imagination, Jeffrey said. In one story, a woman is condemned to spend her last days in the company of a clown’s mask, grinning at her in derision.

‘And then there is my favourite.’ Jeffrey beamed. ‘Shameless plug coming up, by the way, for the Ravenbank Theatre Company. Our latest production combines a trio of macabre stories, linked together like that wonderful old movie Dead of Night. We’re touring venues across the North, starting next week, with our premiere in Keswick, at the Theatre by the Lake. We call the show Tarnhelm after Walpole’s finest supernatural tale. Who knows, it might become the new The Woman in Black! But I’m not going to spoil things by telling you much more …’

He beamed, allowing himself a suitably histrionic pause. ‘Except to say that the stories we’ve chosen are sure to make your flesh creep. Like “Lost Hearts” by M.R. James, about a young boy sent to stay with a cousin, a reclusive alchemist obsessed with making himself immortal. “The Voice in the Night” describes a sailor’s dreadful encounter with a mysterious oarsman. But my favourite is “Tarnhelm”, based on a legend of terrible misdeeds. Tarnhelm is a skullcap. Put it on your head, and it works a sort of magic. At once, you become an animal. And you become as wild as the animal you want to be.’

‘Time to come clean, Daniel. Do you believe in ghosts?’

Jeffrey Burgoyne’s voice penetrated the hubbub in the crowded bar. The Solitary Reaper took its name from Wordsworth’s poem, and was one of the busiest pubs in Grasmere, as well as the tiniest. People in the village nicknamed it the Grim Reaper, as oxygen was usually in short supply.

Daniel swallowed a mouthful of Old Speckled Hen. ‘I’m a sucker for stories of the uncanny. I must read The Killer and the Slain.’

‘Indeed you must, but that’s still an evasive answer. You sound more like a lawyer than that sister of yours.’ He waved a fleshy hand in the direction of Louise Kind, deep in conversation at a nearby table. ‘Nail your colours to the mast! You say a historian needs to dig up facts, like a sort of scholarly archaeologist. I bet you don’t think there’s enough hard evidence to justify a belief in ghosts – am I right?’

‘If you’d asked me a few years ago, I’d have said so.’

Jeffrey Burgoyne’s protuberant eyes scrutinised him from behind rimless spectacles. The loud, plummy voice, striped blazer and MCC tie suggested a cricket spectator from the fifties. Fixing a stern gaze on Daniel, he morphed into counsel for the prosecution.

‘But now you’re not so sure?’

Daniel gave a lazy grin. ‘The older I get, the less sure I am about anything. What about you, Jeffrey? You believe in the returning dead?’

‘Certainly.’ Jeffrey leant closer, and lowered his voice. ‘Perhaps I just have an unfashionable belief that old sins cast long shadows.’

The trouble with actors, Daniel thought, was that they never stopped performing. As a student, he’d had a six-month relationship with a girl who was a star of the Dramatic Society, and he’d never been sure he really knew who she was. Giselle was sweet and pretty, but unpredictable, trying out personality traits like changes of clothes, forever agonising over which suited her best. She said actors needed to be a mass of contradictions, adaptable yet bloody-minded, sensitive yet thick-skinned. Wherever they went together, she watched people. Studying their turns of phrase and their body language. Trying to peer inside their minds. As Jeffrey Burgoyne was doing now.

‘Monday is Hallowe’en.’

‘Indeed. As it happens, Quin and I have been invited to a Hallowe’en party by Oz and Melody Knight. Their home, Ravenbank Hall, is magnificent. I’m sure they’d love you and your sister to come.’

‘Very good of you, but—’

‘You must say yes!’ Jeffrey Burgoyne boomed, before Daniel could invent an excuse to say no. ‘You’ll both have great fun. Besides, Quin is making his special recipe mulled wine, and that simply has to be tasted to be believed.’

‘Sounds terrific.’ Daniel had been introduced to Quin at the end of the conference. Young enough to be Jeffrey’s son, he was his partner in life as well as in the theatre company.

‘Believe me. And if all that isn’t enough, as an added bonus, we supply a Hallowe’en legend of our very own. A ghost story involving not one terrible crime, but two! Given your interest in the history of murder, you’ll find the story riveting.’

Daniel’s curiosity stirred. Maybe there was no need for an excuse to avoid a party with a bunch of Lakeland luvvies. His fascination with mysteries of the past had led him to become a historian, and make a career out of being inquisitive.

‘Tell me more.’

Jeffrey was in no hurry to spill the beans. Like any storyteller, he loved building suspense. ‘You live in Brackdale, I saw from your bio in the conference brochure. A fair stretch from Ullswater, but no need for you to drive home in the early hours. Stay overnight, we have two spare rooms. Save the misery of having to go easy on the booze.’

‘Louise went house-hunting in Glenridding last week.’

‘Oh goodness, we’re much further off the beaten track. I don’t expect you’ve visited Ravenbank?’

Daniel shook his head. ‘I haven’t lived in the Lake District for long, and Louise is an even more recent arrival.’

‘No need to sound apologetic, old fellow. I grew up in Carnforth, spent seven years at Sedbergh School, and moved to the Lake District after coming down from Peterhouse. Not good enough – one of my neighbours maintains I’m still an incomer. On her sixty-fifth birthday this summer, she was boasting that she’s never visited London, and a few months in Belfast are the closest she’s come to travelling overseas.’

‘If all you’ve ever known is the Lakes, you might decide there’s no need to settle for second best.’

Jeffrey chuckled. ‘You’re a man after old Miriam’s heart. She loves the place, insists the only way she’ll ever leave is when she’s carried out in her box. Mind you, Ravenbank is so isolated that plenty of born and bred Cumbrians have never made it that far. Frankly, it suits us to stay a well-kept secret, we’d hate to become the last leg of a tourist trail.’

‘I bet.’

‘Believe me, it is one of the most beautiful places on God’s earth …’ Jeffrey paused for five seconds, a performer to his fingertips. ‘Yet amazingly, Ravenbank has witnessed two savage murders.’

‘Statistically a rival for Baltimore, then?’

‘You’re teasing, Daniel, naughty, naughty. We even have our very own ghost. The Faceless Woman. All the best phantoms have a suitably macabre moniker, don’t you agree? Her real name was Gertrude Smith.’

‘What happened to her?’

‘She was a young Scottish housemaid who worked at Ravenbank Hall before the First World War. The master of the house, a man called Hodgkinson, seduced her. Unfortunately, he had a mad wife who wasn’t confined to the attic. Letitia Hodgkinson found out about her husband’s affair, and on a suitably dark and stormy Hallowe’en, she crept up behind Gertrude, and knocked her down with a stone plucked from the rockery in the Hall grounds. Then she battered the young woman’s beautiful face into a pulp.’

On the far side of the bar, a man who’d had too much to drink guffawed at one of his own jokes. Daniel picked up a beer mat, and crumpled it in his palm without thinking. His mind was on the story.

‘Go on.’

‘When Gertrude’s body was discovered, her ruined face was covered with an old woollen blanket. It entered Ullswater’s folklore, as the Frozen Shroud.’

‘What happened to the wife?’

‘She committed suicide within hours of the murder, so there was no trial. The whole business was hushed up. Justice wasn’t seen to be done.’

‘It often isn’t.’

Jeffrey took another sip of gin and tonic. ‘Indeed. People were sorry for the Hodgkinsons’ daughter. Dorothy was only thirteen. Nobody cared much about Gertrude, the real victim. No wonder her spirit was restless. A story gained currency that each Hallowe’en, Gertrude would patrol the lane that leads to Ravenbank Hall, seeking retribution for the wrong done to her. Terrifying anyone who chanced upon her – because there was nothingness where there ought to be a face.’

‘Pity you and Quin haven’t managed to catch a glimpse of her.’

‘I’ll say! After the First World War, Ravenbank Hall became a care home run by a charity, but when it closed down, a wealthy hospital consultant turned it back into a private residence. His wife was the last person who saw Gertrude’s ghost. The Palladinos are dead now, but the legend persists.’

Daniel sat back, inhaling the Grim Reaper’s beery air. ‘And the second murder?’

‘Five years ago, and a strange echo of the first. Again, justice was cheated, and the man responsible never stood in the dock.’

Jeffrey Burgoyne lowered his voice, his manner unexpectedly intense. Impossible to picture this plump and pompous fellow, even in his younger days, as a leading man. But he was an accomplished actor.

‘Unfit to plead?’

‘No, Craig Meek died before the police caught up with him. His victim was an Australian woman. Flame-red hair, with a personality to match. Stunning, if your tastes ran in that direction, and plenty of men’s did. But then, a jaguar is a beautiful creature, isn’t it, until it rips out your throat?’

‘I’m guessing you weren’t a member of her fan club?’

‘She was out for herself, first, last and always. Her name was Shenagh Moss, and she liked to describe herself as a therapist with a speciality in massage.’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘Draw your own conclusions, and you won’t go far wrong. She spouted a lot of drivel about reiki therapy and heaven knows what. At least she was skilled enough to make an impressive conquest. Francis Palladino was more than twice her age, but shortly after they met, Shenagh moved in to Ravenbank Hall. Francis was an intelligent chap, but lonely. Strange to say it of a successful man with pots of money, but he was vulnerable.’

‘Where did Meek fit in?’

‘He was one of Shenagh’s former lovers. His name was misleading – he had a violent temper, and had recently served time for GBH. He ran a club in Penrith, but he ended up bankrupt after fiddling his tax. Shenagh had a fling with him, but when she moved on, he felt betrayed.’

‘The jealous type?’

‘Yes, he was a bully. Refused to let go, and began stalking her. Following her home, making silent phone calls at all hours of the day and night. Francis paid for her to take the best legal advice, and a judge slapped an injunction on him, preventing him from making contact with her. The plan backfired, because for Meek, the court case was the final straw. One Hallowe’en, Shenagh took the dog out for a walk and never came back.’

‘What happened?’

‘Francis found her body, poor fellow. Meek had bashed her face in, then covered it with a blanket. Just as Letty Hodgkinson had left Gertrude Smith’s corpse. It was as if Meek had made a crude attempt to update the legend of the Frozen Shroud. If the plan was to throw the police off his scent, it was doomed to failure.’

‘You said Meek died. Suicide?’

‘No, he was killed in a head-on crash with a lorry on the A66 that same night. Fleeing the scene of the crime. The stretch near Threlkeld is an accident black spot, and Meek careered onto the wrong side of the road. So justice wasn’t seen to be done. Except in the crudest way.’

‘I suppose there was no doubt that Meek did kill Shenagh?’

Jeffrey frowned. ‘Absolutely none. A neighbour saw him leaving home that evening, and later his car was seen in Howtown, heading back towards Pooley Bridge, where he rented a flat. Obviously making a run for it after killing Shenagh. Nobody else died in the crash, but Meek was responsible for two deaths apart from his own.’

‘How come?’

‘Francis Palladino never recovered from the shock of finding Shenagh’s corpse. Within a year, he was dead too. Officially, double pneumonia, but anyone with a trace of romance would say he died of a broken heart.’

‘Murder is like that.’ Daniel glanced at Louise. His sister’s former lover had been killed shortly after she’d moved up to the Lakes. ‘One death creates countless ripples. It isn’t just the victim. So many lives are changed forever.’

‘I suppose so.’ Jeffrey considered. ‘Though the callous might say that every cloud has a silver lining. Take Oz and Melody Knight. They were set on buying Ravenbank Hall, and after Francis died, their dream came true. Not that they would have wished him any harm, needless to say.’

‘Jeffrey! I can spot that mischievous gleam a mile off. You’re not being bitchy about anyone, are you?’

The mellifluous Irish accent belonged to Alex Quinlan, who had been sharing a table with Louise Kind and Melody Knight. A svelte figure in a purple shirt and white trousers, he shimmied towards them, sinuous as a dancer.

Jeffrey stroked Quin’s cheek. ‘Bitchy, moi?’

‘You’ll be telling me next that butter wouldn’t melt in your mouth.’

‘Don’t listen to him, Daniel. I’m always well behaved.’

‘Not always, love.’

The people at the next table were leaving, and Louise and Melody came to join them. Melody was probably in her thirties, but her skin was so flawless, it was hard to tell. Her lovely face made Daniel think of a screensaver; you could only guess what hid behind the surface.

‘Daniel, such a treat to meet you in person! And thank you for giving such a wonderful talk.’ She shook his hand. ‘I was telling your sister, I used to work pretty much full-time in the business, setting up events like today’s. But recently Oz took on someone else, to give me more time to pursue my secret passion.’

‘Which is?’

‘The same as yours!’ A full-wattage smile, blinding in its intensity. ‘I love to write, and I’ve started freelancing, covering the conference for Cumbria World. I’ve been dying to talk to you. Any chance you’d let me interview you about your new book about the history of murder?’

‘The Hell Within? Publication isn’t due until next year.’

‘So much the better – I can get in first! What do you say?’

Before he could answer, Jeffrey butted in. ‘I’ve taken the liberty of inviting Daniel and Louise to your Hallowe’en party. Hope that’s all right?’

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘You’ve been telling Daniel about the Frozen Shroud, I suppose?’

‘It’s an extraordinary story. Poor old Gertrude, eh?’

Quin said quickly, ‘Not forgetting poor old Shenagh.’

‘Yes, Jeffrey was telling me about her,’ Daniel said.

‘Oh yes?’ Quin’s eyes narrowed. ‘She came from Penrith Valley in Australia, a world away from our own Penrith. A beautiful extrovert, Shenagh. She loved life, she was full of fun. Did Jeffrey mention that, by any chance?’

‘Well, I gather she wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea?’

‘No,’ Quin said. ‘She certainly wasn’t.’

Melody compressed her lips. ‘I suppose with a murder victim, that’s stating the obvious.’

Jeffrey’s brow knitted, but when he spoke, his tone was breezy. ‘Anyway, there’s no better place to be in the Lakes on Hallowe’en than Ravenbank. You’ll find Oz and Melody are fabulous hosts.’

‘You’re too kind.’ Melody seemed glad he’d changed the subject. ‘At least there will be no kids making a nuisance of themselves, just plenty to eat and drink, good company, and an outside chance of seeing a phantom housemaid. In fact, Jeffrey, you read my mind. I’d just mentioned the party to Louise. Please say you’ll both come.’

Daniel glanced at his sister, who gave a quick nod.