Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

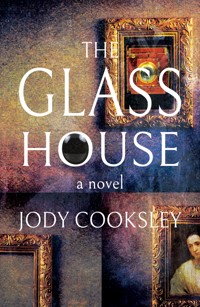

What is a life without Art and Beauty? Not one that Julia chooses to live. And so she searches the world for both, discovering happiness through the lens of a camera. A fictional account of pioneer photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron, and her extraordinary quest to find her own creative voice, The Glass House brings an exceptional photographer to life. From the depths of despair, with her relationships strained and having been humiliated by the artists she has given a home to, Julia rises to fame, photographing and befriending many of the day's most famous literary, artistic, political and scientific celebrities. But to succeed as a female photographer, she must take on the Victorian patriarchy, the art world and, ultimately, her own family. And the doubts are not all from others. As Julia's uneasy relationship with fame grows into a fear that the camera has taken part of her soul, her search leads her full circle, back to India, in her lifelong quest for peace and beauty. A poignant, elegant and richly detailed debut.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 421

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part I — The Artist’s Death

Epigram

1861 Freshwater Bay

1822 Calcutta

1827 Versailles

Stories from the Glass House: Henry Taylor

1832 Paris

1861 Freshwater Bay

1835 Calcutta

1836 The Cape of Good Hope

1861 Freshwater Bay

Stories from the Glass House: Annie Philpot

1838 Calcutta

1838 Calcutta

1861 Freshwater Bay

Stories from the Glass House: Charles Hay Cameron

1839 Calcutta

1847 Calcutta

1848 Calcutta

1861 Freshwater Bay

Stories from the Glass House: Christina Fraser-Tyler (The Rosebud Garden of Girls)

1848 Calcutta

1848 Calcutta

1849 Kensington

1849 Kensington

1861 Freshwater Bay

Stories from the Glass House: George Frederic Watts (The Whisper of the Muse)

1852 Putney Heath

1853 Putney

1861 Freshwater Bay

Stories from the Glass House: Mary Hillier

1856 Putney

1858 Kensington

Stories from the Glass House: Alfred Lord Tennyson (The Dirty Monk)

1859 Isle of Wight

1860 Isle of Wight

1860 Isle of Wight

1860 Freshwater, Isle of Wight

1862 Dimbola Lodge, Isle of Wight

Stories from the Glass House: Mary Ryan

Part II — The Artist’s Life

1863 Dimbola Lodge, Isle of Wight

1863 Freshwater Bay

1864 Isle of Wight

1864 Isle of Wight

1864 Dimbola Lodge, Isle of Wight

Stories from the Glass House: Edward (Charles) MacKenzie

1865 London and Isle of Wight

1867 Kensington

1867 Freshwater

Stories from the Glass House: Lady Caroline Eastnor

1868 Kensington

1868 Isle of Wight

1868 Dimbola Lodge

1869 Isle of Wight

1869 Isle of Wight

Stories from the Glass House: Sir Joseph Hooker

1870 Isle of Wight

1871 Isle of Wight

1872 Lymington

Stories from the Glass House: May Prinsep (Elaine)

1873 Camelot & Freshwater Bay

1873 Isle of Wight

1874 Dimbula Valley, Ceylon

1874 Ceylon

Acknowledgements

The Glass House

Jody Cooksley

Published by Leaf by Leaf

an imprint of Cinnamon Press

Meirion House

Tanygrisiau

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Gwynedd, LL41 3SU

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Jody Cooksley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. Copyright © 2020 Jody Cooksley

Print ISBN: 978-1-78864-911-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78864-920-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig © Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented in the UK by Inpress Ltd and in Wales by the Books Council of Wales.

For my brother, David

Part I

The Artist’s Death

Oh, mystery of Beauty! Who can tell

Thy mighty influence? Who can best descry

How secret, swift and subtle is the spell

Wherein the music of thy voice doth lie?

Julia Margaret Cameron, On a Portrait

1861 Freshwater Bay

Their words still rang in Julia’s ears as she ran to the shore. Stumbling on a pile of tide-strewn pebbles, she put out a hand to steady herself against the breakwater and howled at the stars. How could she ever speak to the islanders again? All her plans had dissolved like dreams, leaving her defenceless. A silly, middle-aged woman, filled with the impotent rage of ambition. Only now could she see it clearly.

Moonlight bathed the damp sand along Freshwater Bay: a sweeping horseshoe curve that calmed the waves in the worst weather. A place of peace. The scene of her first encounter with the Society. How could she have trusted them? And the Signor; he had encouraged her all along, knowing she would be exposed. How had she been so foolish? All the visions in her head were nonsense. All her claims to Art, lies.

Placing her boots beside her, Julia sat to rest on the low wall behind the lighthouse and stared at the shimmering river reflecting from shore to horizon. Reckless of her to seek recognition in the first place; hadn’t she always been told it wasn’t natural for women to crave attention? Weary with sadness, she pushed her bare toes into the wet sand and raised them, watching the wells pool with water and merge again with the rest of the beach. Where was the footprint she had promised to leave on the world? She had carried the promise like a sword for most of her life and yet left nothing. No paintings, no words of any use, no brave new Art. Her only footprint would be transient, would fill with water and sand and simply disappear.

The calm sea beckoned her forward and Julia stood, stretched, began to walk towards it. A smooth surface prettily reflected with stars. It was much less cold than she’d expected and lapped gently around her ankles, welcome and comforting. Julia watched as the dark water swallowed her feet, then her calves. Still she walked, vaguely aware of the drag and swell of her skirts. Overhead stretched the low web of stars that wrapped her island, reminding her suddenly of India, the brightness of long hot nights and the yearning to capture the colour of skies. The sense of destiny she felt and the secrets she uncovered. It was a lifetime ago. A lifetime of making wings only to discover that she was never meant to fly.

Something flapped against her neck and she lifted her hand, touched the silk of her bonnet. Why had she felt the need to impress those fools with a ridiculous hat? Fumbling for the ribbons, she shook them free and threw the hateful thing behind her onto the sand. The tumble of her hair, long and loose, made her a child again. Mama’s Indian sunbird, soaring high above the world to see what others could not. A hopeful princess at a vicious party, with a long pink bow at her waist. They had laughed at her then, and laughed at her now. She was tired of trying to please. All she wanted was to sleep, to forget. Scenes from her life flashed past, too fast to catch and hold.

Julia walked as far as she could. When the water reached her waist, she leaned forward and gave herself to the sea, wanting only to be taken, imagining herself floating forever like Ophelia in her bed of reeds.

1822 Calcutta

‘Tell me what it means.’ Julia traced her finger around the outline of a pink circle, studded with dark blue marks.

‘It’s not for children, ma chère. One day you will understand.’

Julia stuck out her lip; Mama was the only grown up who thought she was too small to understand things. Papa answered her questions. He was fun, striding like a king in his crisp military dress and swinging her in the air. She flounced away from the wall and caught the edge of the table, knocking a silver-backed mirror and hairbrush to the ground. Mama flew across the room to scold her.

‘Seven years bad luck!’

‘It isn’t broken.’

‘Lucky for you. Seven years is a long time to be punished for mistakes.’

‘Two years more than Sarah.’

Mama‘s eyebrows closed in the middle when she frowned. Like monkeys before they attacked. ‘Sarah would never be so naughty.’

She was using her distracted voice, starting to move away. It was important to know. Scrolls and parchments covered the walls of their stilted house, as hard to understand as Mama’s mood. Julia tried again, tugging at her bangles. ‘Why are they painted like that?’

Mama stroked the thick paper, her fingers dragging over the curled edge, eyes focussed on something Julia couldn’t see. ‘It’s a science, ma chère. The stars hold your destiny.’

‘When I’m seven, will you tell me what it means?’ When Adeline was seven Papa had given her a pony he’d won in a game of cards. Seven was special, and it was soon. It was too exciting wondering what seven would bring. Mama shook her head slowly. ‘But I want to understand! Papa says I’ll only understand if I ask questions, but what’s the point if no-one will answer them?’ Mama didn’t like the way he always laughed at her charts. Julia gave her a sly look. ‘Shall I ask Papa then? Does he have signs too?’

‘Very well,’ she replied, rolling up the chart with a snap. ‘But you must have your own. I’ll ask the scribe at Pahor.’

The chart was delivered with a flourish by the scribe’s young apprentice, curled in a thick bundle of parchment and tied with grass. If only Mama would look at her so attentively. Whatever it meant it was pretty. Each of the symbols was painted in double colours, surrounded by a pattern of silver stars on a background of swirling lilac and indigo clouds. How wonderful to make such pictures. She would ask for paints for her seven present. Julia turned to the scribe’s boy, waiting patiently, and asked him in Hindustani what it meant.

‘Master says you will live two lives. One will be taken by waves,’ he replied in English, intoning in a flat voice as though reading from a script, his head bowed. ‘One will be broken by mirrors and glass. You must watch for them both.’ The boy raised his head, briefly catching Julia’s puzzled gaze before casting his eyes back to the floor.

With a stony expression, Mama took the chart, gave him a parcel wrapped in cloth and a wad of paper rupiah to deliver to the scribe. Then she ushered him out to the door, before retiring to bed with a headache. Was Mama somehow displeased? Paintings usually made her happy.

Julia searched all over, finally discovering the chart in her mother’s dressing room. It was inside a drawer, lying on top of a frayed yellow envelope containing two small white cotton caps and two dry locks of hair tied at each end with pale green string. Perhaps Mama was planning to make a doll for the special seven present? A doll with old dried hair? A horse would be better. Even one with thundering feet and a head that jerked on its reins like Adeline’s.

She brought her finds down to supper. But, as she held them up for inspection, a swift hand struck everything to the ground. What had she done to make Mama so angry today? Sudden tears blurred everything but the sight of the pear-shaped diamond on her right ring finger as it flew back towards her face. Fine-cut edges left a weal across Julia’s cheek the size and shape of a rosemallow flower. It still smarted the following week, when she and Sarah were taken to be schooled in Paris.

1827 Versailles

Julia’s birthday fell in high summer, when the scent of lavender in Grandmamma’s garden was strong enough to draw tears. A feast was spread on long tables, under the shade of the willow. Girls in muslin brought cards pressed with wild flowers. The number twelve was iced in sugar roses on a tall, white cake. She walked across the lawn to lunch feeling like a princess, hair loose at the back, a secret smile, a wide pink sash around her waist.

Afterwards, she hid in the washroom and wept. To think that she had spoiled such a perfect day by listening to the grown-ups! That coven of old women in jet-black lace and beads, always talking, crouched like spiders over their iced tea and four o’clock gin, crumbling madeleines between their pointing fingers. Yet, crawling along under the table to catch one of the kitchen cat’s new silver-striped kittens, she’d heard her name and stopped to listen.

‘I’m afraid it’s no use pretending we’re waiting to see how she turns out. Julia’s certainly not like her sisters.’

Her ears strained to hear the second, quieter voice.

‘Poor thing. So unlike her own mother too. Sarah’s the very image of her, but Julia…’

She stayed crouched below the table, breathing in tense, shallow gasps with the effort of remaining silent. A light breeze lifted the tablecloth’s edge, briefly exposing her left knee. Don’t let them notice. A sudden vision of Grandmamma’s fierce face brought the acid-sharp taste of tomatoes to her throat. Sarah had warned that too many slices of tart would make her sick.

‘You must admit that, given her heritage, Julia is something of a surprise.’

Another pause. The sound of glasses being filled. Then Grandmamma spoke. ‘She’s young. Young ladies do change. And she’s still quite the garçon manqué.’

‘She’s of age today. There’s nothing about her looks that will improve from here.’

‘And that figure! She’s as dumpy as a sow.’

Hot tears pricked the edges of Julia’s eyes. She would not cry. Not here, where Sarah would demand to know the reason and delight in sharing it among the guests. Grandmamma must surely contradict them? Dry grass prickled unbearably at her ankles.

‘Julia’s bright and intelligent. She will make a good wife,’ the old woman spoke slowly, precisely.

‘She’s unlikely to make a good mistress…’ the voice paused to accommodate a burst of laughter. ‘But perhaps she doesn’t care.’

Did she care? She didn’t want to. But her eyes were wet, her stomach churning. A scraping of chairs as the old women rose sent Julia scuttling along the grass to the other side of the table, where she stood and brushed the debris from her pinafore, glancing around to see if anyone had spotted her, before running into the house and upstairs.

Music carried from the garden, rising and falling in jarring snatches. It would serve them right if she threw a bucket of water from the window. They weren’t friends anyway, just boring little girls Grandmamma had gathered from neighbouring chateaux to fill out the day, just as she collected adults for her salon. Peering into the worn glass above the washstand, Julia examined her features with interest for the first time in her life. How had she never noticed she looked nothing like Sarah and Adeline, with their rose cheeks and delicate brows? Staring from the murk of the antique mirror was the colourless face of a peasant, with broad, rough features. Only the eyes sparkled, as though refusing to know their place. Slowly she turned her head from left to right, admiring her eyes with their heavy lids and deep amber-brown. From their depths flared tiny orange lights, like flames.

Noises mixed with the music—clattering hooves, the crunch of gravel under carriage wheels—signalling that the guests must be leaving. If they hadn’t missed her before, they would surely be looking now. Grandmamma would never forgive such inhospitable behaviour. Julia, embarrassed and ashamed, jumped up so quickly the wooden stool fell backwards onto the floorboards with a smack that echoed in the bare room. Hiding for so long, she’d missed everything: the dancing, the cutting of that wonderful cake, the girls singing her name as they crowned her with a headdress of gold paper. Such a wasted day. She set the stool straight and peered through the window. At the gates by the front of the house stood perfect Sarah, handing paper twists of sweets to the guests, holding their hands and bobbing down in a theatrical curtsey. Something glinted in the early evening sunlight. A crown: the crown of a birthday girl worn with the confidence of a real princess. For a brief moment she felt nothing but hatred for them all.

Grandmamma put it down to excitement, even after the fight for the crown. Patronising in that special way of elders and betters, no questions asked and the children sent off for an early bedtime. Julia hugged the lumpen body of her doll, Amina, dressed in a thin white handkerchief and sharp-tufted wings made from magpie feathers. Moonlight slanted across her sisters’ faces, lighting the delicate curves of their cheeks. Adeline still looked peaceful and kind, her mouth soft. Sarah’s lips were flatter, giving her smile a sarcastic edge, even in sleep. Her own neat wooden doll lay by her head. Cake crumbs stuck at the corners of her mouth and the sight brought another spike of anger. The birthday girl should know how the cake tasted. She would go down at once to see if any was left. Wrapping herself in Adeline’s silk gown she tiptoed to the door and felt her way along the corridor. No one would follow her even if they woke; Adeline wouldn’t want to be told off and that baby Sarah was still scared of the dark. Who would want to be like them anyway?

She should have confronted them when she had the chance. So what if she looked different to her family? The lights in her eyes were fierce as fire. This was how she should be. Strong. Beautiful as the flames in her eyes. Because beauty could be found everywhere, it could be captured and discovered, she could feel it. She could create it. And it was part of her, whatever those old women might say.

Ideas formed in her mind. Visions of the walls in the Louvre; the frescoes in the church at San Sebastian; the portraits in the Long Hall at school. Pictures of ordinary people, made beautiful with bright colours, threaded with light and tipped with gold. She would learn to paint! Already her head was filled with ideas. No one could prevent her from becoming an Artist. As an Artist she would have more beauty at her fingertips than her sisters could imagine, and such beauty would never grow old and fat like Grandmamma’s.

Forgetting the cake, Julia half-ran to the study and seized her short quill from the pot. Thank-you cards were stacked in the pile she had been made to start. Those that were finished were stamped roughly with the family seal and bright red beads of wax scattered the desk like a blood trail. Drawing the newly sharpened nib across the soft pad of her left hand she scoured a cut and squeezed it quickly onto the pages of her letter book, scratching thin red lines of script.

Until her twelfth birthday she had neither imagined growing up, nor considered what her future life might bring. Now she knew she would be an Artist. When she’d finished writing, she dried the ink, threw the blotting paper onto the embers of the fire and hid the promise in her reticule, drawing the strings up tightly.

Stories from the Glass House:Henry Taylor

A wholly natural scientist: inquisitive, determined. Always wanted to get to the bottom of things, to understand them properly. Very unlike a woman in that regard. Such a fascination for collecting the natural world, for sorting it into piles and putting it into boxes that she could label. If she’d been in possession of any kind of masculine patience, she may well have discovered something astonishing about the order of things. But she possessed nothing of the sort. She was impetuous, impatient and she only ever wanted to be an artist anyway. Of that she was certain, although one could see how very unhappy it made her.

My wife, Alice, always claimed that the camera was her saviour, and photography really the perfect thing for her. It was creative science and she made sure she understood the chemistry behind it, even if she did break all the rules. Such a feminine approach, quite mad really. But then someone like Julia Margaret could never have done anything ordinary.

We were all in thrall to her once she was on the throne in her Glass House. I’ve no idea how she persuaded me to wear that hat for my portrait. It wasn’t mine, probably belonged to her husband. She dragged the hat, and a cloak too, from her costume box. A dreadful floppy velvet hat, the kind a wandering minstrel might wear. It gave me a soppy look, quite at odds with my work. Alice said it made me look romantic, but I regretted it afterwards. I’d needed a photograph I could use for my playbills and it simply wasn’t serious enough. Though I did refuse to wear the cloak, which she’d covered in stars like the robes of a wizard. So perhaps I got away rather lightly. A great many of her poor subjects were bullied into the wearing of such costumes.

Julia Margaret loved the very idea of magic, and superstition was rife in the whole family. Been in India too long I should say. The mother was half mad with it, even when I was there, and what happened to those poor drowned babies was enough to send anyone screaming. I don’t think Julia Margaret knew. She was so young she would have missed the worst of it. It affected all the sisters though, in their own ways. Adeline was dreadfully melancholy. Virginia was terrified of everything. Sarah was the only one of those Pattle girls with her feet on the ground; she knew what she wanted in life and woe betide anyone if they stood in her way, even her own sister.

Julia Margaret pretended superstition was all nonsense, but for her there was magic everywhere, not just fairies in the trees but a sense of the mystical about everything. She was filled with these romantic notions about the world, always expecting something to happen. In the end I suppose it did, though she waited long enough for it to come.

1832 Paris

‘Don’t make such a cross face Sarah. It’s a wife’s duty to be with her husband.’ Mama looked across to where Julia sat, wearing a riot of colourful silk roughly sewn into a dress. A muddled heap of brushes and a little wooden easel lay at her feet. ‘Julia understands why I must go back, don’t you darling?’

Julia didn’t wish to understand; she would far rather her handsome father was sitting before her, scented with cigar-smoke and whiskey, the promise of parties. Mama was no easier to talk to than Grandmamma, sitting straight-backed in formal lace while her daughters lounged on the grass. A light dusting of chalky powder lit her cheeks. The pear-shaped diamond sparkled on her finger. In the two years since her last visit, Julia had painted tirelessly; Adeline was the only person to have commented on her work. Approval from her elder sister was not worth having, she liked everything. If only Mama would show some sign of pleasure in her efforts.

‘Little Virginia won’t settle until I leave this time. You sisters will need time to get to know each other.’

‘She seems terribly shy.’ Julia tossed her head. That baby had done nothing but cling to Mama’s skirts since she’d arrived. Worse than Sarah for her constant hovering by the looking glass, always swishing her skirts and dressing her hair. As if she wanted people to notice her. As if they wouldn’t anyway. Already it was plain to see that Virginia would be the most beautiful in the family.

‘Do you like my robe? Adeline says it’s enchanting.’ Julia performed a theatrical twirl that flared out her silks in a small coloured dome, like an Indian parasol. She was proud of the clothes she made, never using patterns but forcing the fabric into shape with heavy stitches that Madame sadly remarked could have fixed a fisherman’s net. There were bright silks and satins for warm weather and evenings, velvet for the colder months and everything was liberally trimmed with ribbon and glittering paste jewels.

‘It’s certainly interesting.’ Mama smoothed back her curls and patted a tortoiseshell hair-comb into place. Perhaps I will ask Madame to arrange some dressmaking lessons.’

Sarah scrubbed at the paint smear on the shoulder of her pale blue dress. ‘If these marks don’t come out, I shall need someone to make me a new dress,’ she said, frowning. ‘Don’t you ever clean those filthy brushes of yours?’

‘Delacroix never cleaned his brushes. He said it filled his work with the ghosts of his other paintings. I rather like the idea, as though looking at one painting might mean looking at them all.’ Julia picked up a brush and swept it through the air. She’d been making a special study of paintings in the churches that dominated every street near their school in St Germain. Graphic depictions of martyrdom in bright jewel tones. Such paintings generated questions Madame found it difficult to answer, but Julia kept a list in her notebook, promising herself that, one day, she would be able to order as many books as she wanted, about whichever subjects she chose.

‘You’re not an artist, and I very much doubt you ever will be.’ Sarah aimed her words with a sibling’s affectionate spite. ‘Grandmamma says you are wasting your time.’

It was a secret Julia wished she’d never shared. Sarah had a nasty habit of storing information to use unkindly. And she fawned all over Grandmamma, dutifully rubbing her swollen ankles, brushing her thinning hair. Did they think she didn’t know about the wigs? Soon the old woman would fade away entirely, like her legendary beauty, and she would leave nothing: no legacy of great works, no lasting kindness on another’s life. Such an end was everything Julia dreaded. She held up another brush and made as if to throw it at Sarah, narrowing her eyes.

‘Do stop that Julia, you’re much too old to engage in such silly behaviour. Let me see.’ Mama retrieved the canvas from the grass, holding it in front of her and turning it from side to side to consider the unfinished image. Proportionally the figure was strange, the perspective of the background skewed, the wild brush strokes clearly visible. Julia was pleased to recognise the shock on Mama’s face.

‘It is a likeness. Of a kind,’ she said at last, gingerly replacing it to rest against the legs of the garden seat.

Julia scowled.

Why on earth should a painting need to be a likeness? People should care how it made them feel. ‘It’s an image from my head! How do you know what it is supposed to look like?’ She jumped to her bare feet and Mama gave a tiny cry.

‘Julia! You’re almost a woman, I should not need to remind you that it’s unladylike to go about the place without shoes.’ Mama threw up her hands and Sarah smirked, stretching out her own legs, the ends of which were neatly buttoned in high kid boots. They knocked against the edge of the painting and it tumbled face down onto the wet grass.

‘Look what you’ve done!’ Julia had worked for days on the canvas, each stroke a labour of love as she tried to capture the beauty of the colours she saw inside her head. It was ruined. Wet colours streaked the canvas, giving the impression of a world beginning to melt. If Sarah thought she would paint her portrait now, she was mistaken.

1861 Freshwater Bay

Perhaps, if she had learned to paint properly, like the scribes, she would have understood Mama. With such talent she could have travelled the world, not followed Sarah back to London like a tail. She would never have met Emily, never found this island, never met those water-colourists and their silly Society. Imagine the imperious Lady Caroline trying to paint their Calcutta house with its stilted legs, the gardens of mango, neem and banyan spreading below. Imagine her trying to catch the flashing colour of sunbirds, or the long limbs of monkeys as they streaked through the canopy. She would faint clean away. If that woman had ever done anything half as interesting, she would eat one of her ridiculous bonnets. Little wonder they couldn’t understand her work. Julia leaned back further, and water filled her ears with a rushing roar that sounded like laughter.

Perhaps she should have stayed in India. She’d never felt alone there, even as a child. The house teemed with gardeners, bhisti, the men tending chickens and cows; she would follow them everywhere, sitting cross-legged in the dust to watch how they cut and pushed and dug every day to keep an elegant country house in the wild of the jungle. In the shade of the basement there was always someone to listen, to reward her efforts at Hindustani with hard boiled-milk sweets. But they were servants, paid to smile at children.

Of course she was alone. She had always been apart from the rest; nowhere more than at school in Paris, hiding from Sarah in their attic bedroom with its walls as grey as the city. Every balcony and apartment stained with the same peeling paint. The malevolent spires of the cathedral, the broad stone buildings with windows shuttered in hostile pairs. Even the flagstones were square. How could she have hoped to be inspired there? All those commercial painters with their works hung on railings, depicting the same depressing scenes—the banks of the Seine with a swirled grey sky above black bridges in decreasing lines; blood-red geraniums studding iron stairs. Why would anyone want to hang them in their houses? They were the very opposite of what Art should be, ugly.

Her chart was the only colour she saw in those years. Her promise was the only thing that got her through school at all. She had carried it her whole life. Now it would be soaked and ruined, ink running into cloth as her reticule floated away, out of reach.

1835 Calcutta

‘I’m eternally in your debt, Miss Pattle. I’m not entirely sure how I can express the extent of my gratitude for the time and care that you’ve taken over my… affairs.’

The young man’s eyelashes were remarkably long, his cheeks unmarked by sunlight. Such fresh blood was usually a good bet. If she could get to them before Papa, they were so much likelier to work for good, rather than dissolve into dissipation. This one had, unfortunately, slipped through Julia’s net for several weeks. As a result, he had been persuaded to buy horses, dogs and all the trappings of a life he could not afford and then been introduced to the pleasures of native whiskey and card tables to make amends.

‘Without your tea and kindness, I may very well be ruined.’

‘Ruination is something my father bothers very little about.’ Julia smiled as she spoke, but her words were heartfelt; she was deeply sorry for those newcomers to India that suffered at Papa’s hands, the so-called griffins that he led astray.

‘I have only myself to blame, and your kindness to thank for saving me.’

‘Just remember to speak kindly of him, should anyone ask.’

Returning to Calcutta had been a bittersweet homecoming for Julia. Most things were as wonderful as she remembered: indulgent servants, the stilted house, wild animals in the courtyard. Mama was still difficult—fierce, superstitious and challenging. Papa was as powerful as ever. But salon-worldly Julia saw Major James Pattle quite clearly for what he was—a charming rogue.

‘He’s a very great man, he doesn’t realise that not all of us can manage the lifestyle he prefers. I’m sure I would’ve very much enjoyed it,’ the young man replied.

Julia noted his wistful tone. ‘It’s not a life to desire, Mr Carlyle. You’d do better to spend your time working to stop these dreadful crop pests. Do you wish to spend your evenings drinking and gambling when you could be changing lives? Did you know that they leave girl babies out in the jungle for the tigers to take because they’re too poor to pay dowries?’

Now he looked as though he might cry. Really, what on earth did these silly young men think they were doing out here? This country was a playground for them, and Papa certainly didn’t help. Yesterday he pocketed such a large bribe for settling a land dispute that he’d promised jewellery when the stone-sellers came from Kashmir. Sarah was already having designs drawn. Aquamarine, she’d said, to match her eyes. She’d do better to give it to the poor. Julia had seen the woman who stood behind the eager farmer with his outstretched fist of rupiah; she’d seen the way the woman watched the dusty floor, a cloth-wrapped baby perched on one hip, two silent, skinny children pulling at the yellow wrap of her sari. If she could do anything to help, then she would. It was too late for Papa, but there was no reason for them all to follow him. There would be time enough for painting when she’d put things right.

‘I’m forever in your gratitude.’ The rattan chair creaked as he rose and gave a deep bow. A flush crossed his neck as he straightened, twisting the straw hat he held in his hands as though he meant to destroy it. ‘I… if I… I mean, I don’t have the means to ask… not now… but perhaps if you’d wait, if I speak with your father I can…’

Julia gave a sudden, sharp laugh. ‘Don’t flatter yourself. Though I care what happens to you, it’s only because you have the potential to do some good in this country if you apply yourself. I don’t wish to see that potential wasted. I try to make myself useful to anyone who might suffer at my father’s hands… and I’m more than content without a husband.’

The relief on his face as he left was clear. He was the second man to have confused her charity with ambition. Did the future hold nothing but an unappealing choice between the life of an endlessly dutiful daughter and a marriage of pity?

Calcutta had grown, and it was brighter than the city Julia remembered. Buff-white buildings, flanked by tall masts at the harbour, the markets in the redbrick bustle of Chowringee, all edged with the vivid splendour of the jungle. Possibilities unfolded. Julia was no longer a child, she was a young woman, allowed to ride, take up shooting and frequent the city’s many ballrooms. Glittering with gold braid and self-importance, the parties were glamorous and brash, full of pale civil service daughters, keen to fulfil their duty and find a match.

Julia soon regained her fluency in Hindustani, seeking out servants for conversation while the others took naps—such a waste to lie under nets all afternoon! If she was ever to discover her purpose, she must push herself as hard as she could. A deep satisfaction came from simply looking at the spines of all the books that filled her rooms from the daily packages and deliveries. Finally, she had her dream library of philosophy, essays and scientific thought. All that remained was to read and understand it all.

‘I find that I’ve missed you, Julia. You’re still as curious as you were when you were small and your energy for life matches only your father’s.’

Julia swallowed. Mama was not usually complimentary unless she was about to deliver a blow; she hypnotised her prey like a cobra. Still she had been working hard to gain Mama’s approval, helping with the dinners and parties, the picnics, games and outings; scattering seeds of discussion from the theories she learned while the rest of Calcutta slept in the afternoons.

‘I’m surprised to hear you say so. I’d always thought Virginia was your pet.’ And everyone else’s. Her little sister was tall and elegant, with a slender figure and a graceful neck. On the day she arrived in the city, crowds followed the carriage all the way to the house and Julia, perfectly invisible by her side, had spent the journey ignoring them, her nose in a book.

‘Of course she’s my pet! But I don’t know how I managed without all the things you do. Perhaps I’m weary of parties, as your father suggests, perhaps I am old…’ she paused, obviously waiting protestation, but Julia was not in the mood to flatter and, really, agreed with him. Papa boasted the constitution of an ox and his dissipation had done little to dull his looks, which still drew women and men to his side. But while the heat burnished his complexion and streaked his hair, the years of children and travel were causing Mama’s famous colour to fade. She spent more time than ever with the scribes and astrologers that frequented Chowringhee, and her superstitions worsened by the week. ‘I find I can’t bear the thought of any husband taking you away from me.’

‘I don’t think we need worry about that, Mama.’

For a moment Julia thought she would cry, a reaction she’d tried hard to train herself out of in the wakeful dark of Paris nights. She had yearned so long for a sign that Mama found any pleasure in her company.

‘Why ever not? You’re a catch here, my dear, and quite wonderfully engaging. You have these men eating out of your hands. I saw the look Mr Carlyle gave you.’

Should she confide her fears? Knowing Mama, it could very well be a test. Julia willed herself not to break. ‘Perhaps I’m quite satisfied as I am.’

1836 The Cape of Good Hope

‘May I see?’

Julia looked up, surprised, to see a man of advancing age bending his neck sideways as he attempted to read the name on her volume of poems. She held it out for him to take and gave him an appraising look. A writer, or a scientist, perhaps. Certainly someone of great interest to an Artist, such as herself. He was a walking story. His dress was neat, but his hair stuck out around his head as though he need not bother with such mortal trouble as a hairbrush; his eyebrows were wild and his eyes shone curious with what she recognised as the joy of knowledge.

‘Ah, Keats. A worthy accompaniment to such a fine afternoon.’ The stranger continued to stand, turning the pages of the little volume as though searching for something.

‘Are you a guest here?’ He certainly hadn’t been at table in the last week; she would have remembered such an appearance in this dreary hotel. Mama had insisted on the Cape for recuperation from a serious chest infection, but it felt like the ends of the earth, as though her family had decided India’s chaos and charm were simply too much for her. She had been wandering the corridors for a week, learning the formal routines of recovery, the steam baths and bland food; silently acknowledging the other guests with their pallor and quietude. Perhaps life here was about to become more interesting.

‘I arrived today, from Feldhausen. Quite a journey in this heat.’

‘Perhaps you’d care to join me for some refreshment Mr…’

‘John Herschel. And may I know the name of such an erudite reader?’

‘Julia Margaret Pattle. And I’m not sure that the reading of Keats would mark me as erudite.’

‘Indeed?’ he raised a wayward eyebrow. ‘You’re not enjoying his words?’

‘Truthfully, it’s the third time I’ve tried,’ Julia sighed. She’d brought dozens of volumes of poetry, determined to put her convalescence to good use. By now she should be old enough to write such verse and she was far from home, what could be more conducive? Perhaps words were to be her vocation. She’d thought it would be easy to write. Poetry was, after all, of the emotional realm. Some of the best of the Romantics were women, though she could remember none of their names. They were always just someone’s wife, someone’s sister. Her own poems would change the way feminine poetry was viewed; raise it to a new height. If only she could understand it. ‘It’s one of those volumes that everybody tells me to read and, when I do, I can’t help feeling I’ve somehow missed the point. I don’t find it difficult to disagree with popular opinion, but there’s always a nagging doubt, when others are so sure, that if one disagrees then it’s oneself who’s missed the point. Please, can I offer you something?’

The waiter had arrived and was standing by Julia’s chair with an air of expectancy and a supercilious glance at Herschel, who had made himself quite at home; his long legs, clad in bold broad-striped morning trousers, rested on the free chair by his side.

‘I rather hope you’ll join me in some champagne,’ he said, pulling a serious face that didn’t suit him. ‘After all, it’s my first of afternoons, and you’re discovering Keats. There’s much for us to celebrate.’

Julia rarely drank before six, but she had her father’s head for it and, besides, her intuition was indicating that here might be an element of destiny. She took a deep drink, enjoying the light, cool then warming sensation of the bubbles as she swallowed. She was always quick to mark out friends, enemies and those who were worth the trouble of neither. Time had shown her that her first instincts were generally correct. As she watched Herschel’s eyes darting across the lines, she already felt a fondness growing, a sense of many long, enjoyable conversations to come.

‘Aha! I knew it would be here. Now close your eyes and think, really think, about what this might mean to the reader.’ He held the book before him and intoned in a beautiful, halting style quite perfect for the words. ‘Bright star, would I were steadfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night, And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like Nature's patient, sleepless Eremite, The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth's human shores, Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—No—yet still steadfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow'd upon my fair love's ripening breast, To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest, Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.’

‘It is utterly beautiful!’ she exclaimed. The more so because it made her feel, with all the strength of her youth, that her destiny was not to be loved like that, but to be a bright star. She had only to get away from home. If her sisters were here no one would be reading her poetry. Mr Herschel would be fawning over Virginia, or allowing himself to be bossed by Sarah, and she would be sat in the shadows, watching them. Perhaps her worries that she would be abandoned as they got married were unfounded. It would be easy to exist apart from the Pattles, in this charm of independence.

‘A toast to Mr Keats!’ He raised his glass and grinned. ‘He writes, I think, about the Polaris, the North Star. It’s the brightest in the firmament and the star around which all others move.’

How had she not known that? She had watched the stars without any thought to discover their secrets. Tomorrow she would spend the afternoon in the hotel library and begin to learn astronomy. It would not do to feel ignorant. ‘I detect a hint of bias to the subject.’

‘His poem isn’t really about stars.’

‘Of course not! It’s about his one true love.’ A youthful thrill shook Julia’s voice. How daring she was to sit here, drinking alone with a man she had only just met and talking airily of love as though she did so often.

‘The stars themselves may well be my one true love.’

Julia at once determined they should become great friends. Didn’t she love the stars? And now she loved champagne too. So much common ground.

‘The new observatory at Feldhausen is to my father’s design, the biggest telescope ever built. I call it the Gateway to Heaven. I came back to check on it, make some more observations, collect data charts from the records. Now I plan to spend some weeks figuring out what is beyond what we can see.’

‘How can you see further than the stars?’

‘Mirrors, my dear girl. Very powerful ones. With the right magnitude and the right series of mirrors the heavens themselves become visible to the human eye.’ Herschel took a small silver pencil from his breast pocket and drew inside her book of poems a series of ovoid shapes increasing in size.

Julia tried to imagine life spent peering up through a small lens at the night sky. Glasses and mirrors; it was surely no coincidence the fates had brought her this extraordinary man. Could she be an astronomer? It seemed a solitary sort of life. Not quite the cultural storm she’d intended to create. But it was romantic. To see beyond the stars, beyond the sight of sunbirds. Seeing what humans could not see. That would be wonderful.

‘I understand that the stars are really suns. I imagine planets like ours for each of them.’

Herschel raised his glass. ‘Your imagination is admirable.’

Julia flushed with the pleasure of praise from such a man. ‘It’s late Mr Herschel, and I must go to dress. But I’d very much like to learn more about the stars and your mirrors. Do you have a dinner companion this evening?’

‘Indeed I do, but he’ll be as delighted to make your acquaintance as myself.’

Julia nodded, and Herschel watched her disappear, deep in concentration. Her face, though plain, was delightful in its earnest animation and she cut a striking figure in her flowing garments as she walked, her head bent in thought as though she did not expect a single eye to appraise her and would not notice if it did.

‘Since I appear to be the only person who’s not here for the sake of my health, I believe it must be down to me to lead the charge.’ Herschel raised a hand for another bottle and beamed at his guests.

‘My health already feels quite restored and there is clearly little lacking in Miss Pattle.’ Charles Hay Cameron, Herschel’s friend of many years, leaned back in his chair and smiled at Julia. Although twice her age, he cut an imposing figure with his elegant clothes and long, fine-flowing hair and beard.

‘Might I enquire after your health?’ she asked anxiously. ‘You know why I’m here, but you seem never to have lived anywhere except hot climates for any length of time, so I must assume, for you, that India isn’t the problem?’ Julia had already discovered that Cameron, a widowed lawyer, was the son of the Governor of The Bahamas. He had travelled to India in the firm belief that the country required expert legal assistance and had instantly fallen in love with the place and its people, all of which combined to win Julia’s approval. She was exhilarated by the conversation, not least because she was alone in a foreign land. For the very first time she was meeting people, interesting people, away from her family and their preconceived assessments. More importantly, she was meeting interesting people away from her sisters; if Sarah and Virginia had been there, these men wouldn’t have said twenty words to her, she was sure of it.

‘Alas, India is the problem. I’ve just completed my work on the Penal Code. It’s taken many, many years, and I’ve been told that I’m quite exhausted. I find I must be tired, since I acquiesced to rest at all.’

‘Your diligence is to be commended! In such a country there must hitherto have been merely local say so.’ Herschel leaned in intently.

‘Well it’s not entirely my own work but, yes… an immense undertaking. A double tour of the country, interviews with more local regulators than any man should have to see in his lifetime, and the learning of three dialects of Hindustani.’

‘A wonderful language,’ said Julia, in the dialect of Calcutta. ‘Your work will undoubtedly change the country for the good.’

‘I’ve begun to wonder just what’s needed for the good of India,’ he replied in the same language, ‘For a moment I lost my faith in progress, and I am yet to be convinced of the ability of the English to govern there. So, I’m here, for the time being, to rest and gather my wits.’

‘I don’t think it will take you long to gather them,’ said Julia, returning the conversation to English with a sense that Herschel was beginning to feel a little left out of his own party. ‘But don’t give up on India in this hour of her need. There are few enough good men willing to create the stability she needs.’ Julia thought of Papa, his superficial politics and pocket lining, and became vaguely embarrassed. ‘I could lend you some poetry to soothe your mind. Mr Herschel has quite changed my opinion of Keats with his reading of Bright Star.’

‘You’ve never struck me as the romantic type, Herschel?’

The scientist gave a rueful smile. ‘Indeed, I’m not. I feel it keenly as the one great failure of my life that I’ve never known romantic love.’

‘I’ve heard that it’s never too late to find love,’ said Julia, carried away with her own sense of romance and oblivious to the effect of her words. ‘But if you spend too long looking up at the heavens, or gazing into books of law, I’m sure neither of you will ever find your happiness on this earth.’

Julia extended a hand, loathe to leave her new friends, although Cameron would eventually return to Calcutta, and Herschel had been promised a weekly letter. In their few weeks together she had learned more than in all her years at school, grown in confidence and poise and loved them for it. They had both come to see the carriage leave, and the three stood watching the drivers throw trunks onto its roof, shinning across and through the windows to tie them down with lengths of thin rope that they held between their teeth.

‘I’m certain you’ll help me discover something wonderful! You seem to know the answer to every matter of science, and yet you’re perfectly willing to listen to my foolish observations.’