Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

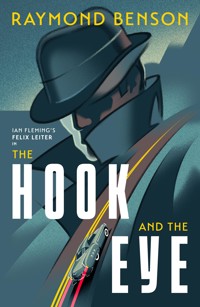

FELIX LEITER – JAMES BOND'S TRUSTED FRIEND AND ALLY – TAKES CENTER STAGE IN A BRAND NEW ADVENTURE BY LEGENDARY BOND NOVELIST, RAYMOND BENSON. It is 1952. Felix has lost his job at the CIA and finds himself working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency. What starts as a simple surveillance job turns into anything but when Felix stumbles upon a murder and a cabal of spies embedded in Manhattan. Hired to transport the impossibly beautiful and impossibly secretive Dora from New York to Texas, Felix is thrust into a non-stop adventure, where danger and deceit lie in wait around every bend in the road. The Hook and the Eye is a mystery, a romance, a spy story and a postcard to a lost Americana. It is also Raymond Benson at his very best.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Author’s Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

vii

viii

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

Cover

Frontmatter

Contents

Begin Reading

Author’s Note

Felix Leiter appears in Ian Fleming’s first, second, fourth, seventh, eighth, and twelfth novels. Ignoring the actual dates of the original publications of these works, Bond historians have long conjectured when in the real world the events in these stories may have occurred. In the late John Griswold’s excellent study, Ian Fleming’s James Bond—Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming’s Bond Stories, the author speculates that Fleming’s second novel, Live and Let Die, actually takes place in January and February of 1952. Moonraker happens in May 1953. The action of Diamonds are Forever is between July and August 1953. Many online fan sites have adopted this perceived timeline (or very similar ones) as gospel. Given this conceit, Felix Leiter’s mishap with the shark in Live and Let Die transpired at the end of January 1952. He doesn’t appear in a Bond novel again until July 1953 in Diamonds are Forever. Thus, the following tale takes place in between those two works, during the last half of 1952 to be exact.

Real highways, hotels/motels, and restaurants around the USA that existed in 1952, as well as the states of landmarks such as Carlsbad Caverns National Park, were utilized in the text wherever possible. The New York headquarters of Pinkerton’s Detective Agency (the name “Pinkerton” without the apostrophe-s was used interchangeably) was indeed located on Nassau Street in lower Manhattan in that era. Robert Pinkerton II did spend time in both the Chicago and New York offices.

According to the latest U.S. government Consumer Price Index data to adjust and calculate for inflation, in 1952 one dollar would equal a few cents less than twelve dollars in 2025. Thus, $100 in 1952 would be the equivalent of $1,198.76 in 2025, and so on.

1

November 3, 1952

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

I’m holding in my hand the fate of the world and I don’t know what the hell I should do with it.

I ain’t kidding. The destiny of the goddamn planet earth is sitting right here in the palm of my left hand. My only hand, I might add. The right one is replaced by aluminum and stainless steel. It hasn’t even been a year since I lost it. Ten months. It feels like a lot longer than that, but at the same time it’s as if it happened yesterday.

Without a destination in mind, I walk away from the unmarked federal detention center in lower Manhattan where I just paid a visit to a new resident. I don’t know how long the inmate is going to be there. They’ll be moving the traitor to another secret location in a day or two, likely to disappear into one of the many red tape labyrinths of the justice system and never be heard from again.

Striding aimlessly eastward, I cross the park, wander into the domain of City Hall, and float amidst the multitudes pouring in and out of the building. It’s where the mayor, the City Council, the Board of Estimate, and the presidents of the five boroughs work. All the bureaucracy of New York City is so close I could touch it, but at this moment I just want to get away from it all. The Civic Center building? Who cares? I do consider stopping by the Pinkerton’s office on Nassau Street, which is practically right there at the edge of City Hall Park. Instead, I decide to head toward the entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge. Everywhere you look the streets are crowded with New Yorkers going about their midday business as usual. Taxi cabs, cars, and buses noisily remind me that the city will just keep plugging away, no matter what.

There’s no question that I’m struggling with how I feel about the woman who did a number on me. Don’t get me wrong—I’ve been through this kind of thing before. I’ve been around the block a few times. Women come, women go. It’s true, though, that she managed to get under my skin. I’m mad as hell at her for doing so, and also for what she did afterward.

I grasp the thing in my hand tightly so I won’t accidentally drop it when I turn my wrist to note the time on my Omega Bumper wristwatch. Just after eleven. For a brief moment I have a memory flash of purchasing the watch in Washington, D.C. in ’48, a present to myself right after I’d agreed to work for the newly formed CIA.

A brisk wind wafts off the East River. I return the object to my left trouser pocket so I can use my good hand and the hook in tandem to button up my trench coat, the same one I’d bought in Paris not long after joining the feds. All of that really seems a lifetime ago, and yet it encompasses a little less than four years. Quite a bit happens to you if you blink for a second.

The pack of Chesterfields is in my coat pocket. I tap out a cigarette, stick it in my mouth, and fire it up with the Ronson lighter I’ve had since I was overseas. The thing still works great. It has the Marine Corps seal engraved on one side. I had my surname—Leiter—engraved on the other as a joke.

After inhaling the much needed nicotine, I limp-walk along the sidewalk across Lafayette and—oh, did I mention my leg? Not only do I not have a right arm and hand, but I’m missing a third of my left leg below the knee. I’m a regular circus sideshow act, folks. That clopping sound on the pavement is from a joint corset leg made of wood and stretch leather. It’s got an articulated foot with a hinged ankle. No one really notices it on first glance because my trouser leg covers the prosthesis and my shoes match. But, as I said, I do limp. Can’t help it. People observe my shuffle and the right hook, and they immediately throw an involuntary expression of pity at me. It happens all the time. In response, I simply grin at them as if it doesn’t bother me at all. They think I’m an injured war veteran. I suppose I am, just not from the kind of war they’re imagining.

Shoot, it was part of the job, I keep telling myself. The luck of the draw. The way the cookie crumbles. That’s life, buddy. Que sera, sera. All those clichés apply, so pick one.

As I turn south on Pearl Street, I consider going to Fulton Market and perhaps grabbing a sandwich for lunch. Maybe. I’m not really hungry. Not after that talk I had. It left me with a hole in my stomach. Or maybe it was my heart, I don’t know. A stiff drink would be more appropriate. It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve had a couple of bourbons before noon.

Ah, to hell with it. Whatcha gonna do? as my old man back in Texas used to say whenever he got frustrated. The store was quiet today—whatcha gonna do? The milk’s gone sour—whatcha gonna do? Keep your chin up, son—whatcha gonna do?

Well, he’s long gone. Whatcha gonna do?

I move farther along Fulton toward the East River. Even though it’s chillier near the water, I want to see it. At first I think maybe I could be alone here, but, no, if you’re outdoors in Manhattan you’re never alone. Around me there are women bundled up in coats doing their shopping at the market. Many of them push strollers. There are no older kids about, it’s a Monday and a school day.

And tomorrow is Election Day. I’ve always wondered why that isn’t a national holiday. So many people who could and should vote have to work and can’t get to the polls. I always make it a point to vote. I have a thing about my country, you see. I’ll do my duty first thing in the morning and help send Ike to the White House. There’s no question about him winning. Stevenson has his supporters, but Ike won the world war. That counts for something.

I finally get to the edge of the seaport and the Fish Mongers Association joint, drop the cigarette butt and step on it, and then stand there gazing at the water. Boats and ferries move both ways, up and down the river, under the bridge carrying passengers, goods, whatever.

It’s kind of peaceful. I like it.

But I’m troubled by what I have in my pocket. How it got there over the past month has been a roller coaster of a journey full of mysteries, bizarre twists, and betrayals.

I pull the item out and hold it in my hand again.

It really could change the world. All I have to do is … sell it. And, hey, it would change me, too. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m not hurting for money. But this tiny thing could make me richer than sin. A foreign power would pay me millions of dollars for this bauble.

Of course, if I did that, I’d be a traitor to my country.

I know the object is dangerous. In fact, it’s perilous as hell. It’s a key to unimaginable death and destruction. Several people have died already because of it. Shoot, I almost died myself a couple of times.

I also fell for a woman on the way to attaining it. Who could have predicted that?

Never mind about the heartache, Felix, I tell myself. Whatcha gonna do?

I stare at it there in my palm.

Millions of dollars.

So what should I do with the damned thing?

2

January 31–July 28, 1952

ST. PETERSBURG, FLORIDA

My thoughts go back a little over three months to the beginning of this strange adventure in my so-called illustrious career. A bit of reflection is warranted.

First, though, let me tell you about my fun-filled vacation in Florida!

I spent way too much time in a hospital in St. Petersburg, recuperating from The Mishap. That’s how I refer to it—The Mishap. Sounds like the title of one of those cheap Hollywood crime movies that feature cynical, hardboiled detectives, crooks, and seductive, but dangerous dames. I love those pictures. Anyway, The Mishap …

My job was supposed to be as an “observer” for the CIA on a case that involved a SMERSH operative based in Harlem. SMERSH is a Soviet outfit that runs counterintelligence agencies. One of the group’s tasks is to assassinate Russia’s enemies—spies, political figures, you name it. Sometimes they even kill off their own people if somebody screws up. Suffice it to say, they’re not very nice.

This Harlem gangster also had businesses in Florida and Jamaica. The British Secret Service was handling the bulk of the operation, and it turned out the agent they’d sent was a friend of mine. He was one of the best men on their team, a Double O, in fact. Those guys are the tops. I’d first met him in France while I was still working as part of the Joint Intelligence Staff of NATO in Paris. Several months after what I refer to as the Casino Job, I was transferred back to the States and put through the works in Washington in the fall of ’51. It all happened quickly before the New Year—the brass moved me to New York and I started working out of the tiny CIA branch there. A cozy one-bedroom garden-level apartment on Bank Street in Greenwich Village became my residence amongst the jazz clubs and all the up-and-coming Bohemian artists and weirdos—not that I minded that, I thought it was great. I settled in for an interesting stint in Manhattan. It beat D.C., that’s for sure.

The Harlem case was already on the CIA’s radar and by mid-January I was assigned to it. The FBI had jurisdiction; like I said, I was simply supposed to be an observer, but I never could sit on my hands. Once my limey pal got to New York, I made sure I shadowed him. We hit the bars and restaurants, drank as if the world would end tomorrow, and still managed to do the work. When my buddy, and a girl that was involved in the matter, arrived in St. Petersburg for the next phase of the mission, I met them there.

I admit I made a mistake. I went off alone during the night to sniff around the Harlem guy’s worm and bait warehouse in St. Pete. It was full of exotic sea creatures, some of them pretty dangerous. I should have waited for my British friend, but I didn’t. To make a long story short, the big man’s henchman caught me and fed me to a shark. The bastard fish took off my right arm and lower left leg. Moments of horror that lasted an eternity. The pain … well, yeah. I still have nightmares about it. I find Haig & Haig is good medicine for that, but it only goes so far.

I really don’t know why, but the man didn’t let the shark devour all of me. He got me out of the water—I don’t remember any of that part—and his buddies delivered my bloody body to my cabana at a Treasure Island beach resort with a note that read, He disagreed with something that ate him. Ha ha. Very funny, fellas.

That was the end of the observing.

The Mishap occurred at the very end of January, so I spent the next few months in St. Pete “on leave.” First there was the hospital where doctors saved my life. My face got lacerated and other parts of my body were scarred up, too, so they had to do a lot of skin grafting. That was no fun at all. I do recall the moment when I learned that I no longer had an arm and foot. At first I was monumentally distressed, let me tell you. But then I thought about some of the crap I saw in the Pacific during the war. Hell, I was at the Battle of Iwo Jima in ’45. I saw men get blown to bits. Some of them lived to tell about it, and, believe me, you wouldn’t want to be in their shape and attempt to have a normal existence.

So, with all things relative, I guess I was lucky. I wasn’t completely eaten alive and the villains didn’t finish me off. I was allowed to continue my life and serve my country another day.

But I had a long, hard road ahead of me.

It took three months for my stumps to heal well enough to be fitted with prostheses. The Veterans Administration was in charge of that, and I have to say they took good care of me. My prosthetics doc, a guy named Karolewski, fixed me up with stuff from a company called Hanger. The “below knee leg,” or BK Leg, as I mentioned before, was made of wood and stretch leather. I had to don a thick wool sock over the stump, and I had to build up tolerance on the skin to be able to wear the thing and walk. I had to build up calluses. It was very uncomfortable in the beginning, but over time I got used to it.

On a day when I was in a good mood, I jokingly mentioned to Dr. Karolewski that I could use the BK Leg as a wooden club and beat a bad guy over the head with it. The doc looked at me and said with complete seriousness, “You actually could. Especially with the shoe on it.” By golly, he was right. I stored that information in the back of my mind, and then I thought of something else. “Can you fashion a little secret compartment where I can hide a knife?” I asked him. The man shrugged and nodded. So, ladies and gents, I do indeed carry a six-inch trench dagger that I’ve owned since I was a kid. My father had it during World War I and he gave it to me. It combines a simple knuckle-duster guard with a short, sharp blade. Very thin, lightweight, and potentially deadly. The compartment is on the lateral side of the leg so all I have to do is bend down, easily open it with my left hand, and pull the dagger out by a short string loop attached to the knuckle-duster hilt. I didn’t know if I’d ever have to use it, but it’s better to be safe than six feet under.

The Above Elbow Upper Extremity Prosthesis was more complicated and required a hell of a learning curve to operate. The figure eight harness took a while for me to master putting on by myself. That was a whole week of training. The VA arm is made of aluminum, stainless steel, leather, wood, and lamb’s wool for padding. It’s a dual control, cable-operated miracle of design that works with geometry and one’s own shoulder muscles. I had to intimately get to know the function of the two cables, the harness, the body control motions, and the sequence of operation like the back of my … well, you know.

The arm’s two-cable system works by shoulder flexion. Mind you, essential shoulder flexes have to be accomplished in concert to manipulate the cables and perform basic tasks. I can raise the forearm, but then I have to lock the elbow in position. Only then can I open and close the terminal device—that’s the hook, or pincer—again with a different shoulder flex. To lower the forearm, I first have to unlock the elbow. Then there’s the act of extending the full arm. All of these things take subtle contractions of both shoulder blades and flexing the shoulders.

The elbow can lock in eleven positions. I just have to remember the cycle—pull my shoulder and release it to lock the elbow, and then repeat the motions to unlock it. How high I lift my upper arm or my forearm is dependent on the amount of strength I use to flex. Normal tasks require only a pound or two of effort.

Man, it took some time getting used to. At first I had to take it one command at a time. It was a month of practice, therapy, and just plain work to get to where I could use my prosthesis smoothly and do it without thinking. Now I can raise, lock, grasp, unlock, and lower in a second or two, as well as use the hook damn near like a hand. I found that one of the most difficult things was to tie a shoe! That required too much concentration. When I heard that many amputees would give up on that and wear loafers, I said, “Sign me up for a pair.”

Speaking of the terminal devices, there are a number of hooks I can use for different tasks. You just unscrew the one that’s currently on the forearm and replace it with another. For example, I’ve got the regular pincer-like hook. I also have one that’s just a ring and it can be used to pull and push the steering column shift on a car (learning to drive with a prosthesis was a whole different challenge). By the way, I prefer a manual transmission over an automatic. I could make it easy on myself and simply drive an automatic, but my love of autos won’t let me. I’ve made it a point to master the column shift, goddamn it!

Then came the difficult exercises of learning to aim a pistol and shoot a target with my left hand. I’d lost my gun arm. Let me tell you, I was terrible at it. Still am. I started going to a range to practice every damn day as part of my physical therapy, and I never could hit the mark. I worked with a VA trainer, too, and the guy was very patient with me. I think I got more frustrated with my aim than with any other aspect of my rehabilitation.

Finally, it was time. The car I’d been driving in Florida before The Mishap was an old Cord that had been impounded by the CIA. I didn’t mind. It was on its last legs anyway, I got a little dough for it, and I had another car back in New York. So, on July 28, I headed home on the Silver Meteor, the train that goes all the way up through Tampa, Savannah, Richmond, D.C., Philadelphia, and ultimately to Penn Station.

It was great to be back in the land of the living.

3

August 1–August 13, 1952

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

The CIA had been gracious enough to keep me on the payroll and also make sure my apartment in the Village remained untouched. I felt indebted to Associate Deputy Michael Brinkley, my handler in New York. I’d only just met him when I was put on the Harlem SMERSH job, and we were getting along swimmingly until I became fish food.

The New York office was a tiny ground-floor storefront on Second Avenue, between 51st and 52nd Streets, disguised as an accounting firm that wasn’t accepting new clients. It acted as a splinter off the main HQ in Washington. In January, the branch consisted of Brinkley, another officer named Johnson, a secretary called Marion, and me. We never worked in the office. Only Marion was present on a daily basis to make and receive phone calls and manage incoming reports from Washington. If Brinkley wanted to talk to us, we might meet there in an adjoining room that had a table and chairs and a couple of filing cabinets. That’s it. Otherwise Johnson and I were supposed to be working out of the country on assignments.

Associate Deputy Brinkley and I had a meeting scheduled for August 1. After so many months away, I already had a bad feeling about it before I walked in.

Michael Brinkley’s face registered pleasure to see me with a wide smile and bright eyes … until the sight of the hook poking out from under my suit jacket sleeve caused him to blink rapidly a couple of times. The grin faltered ever so slightly. I get that a lot from people, both from those I don’t know and from folks I knew prior to The Mishap.

“Felix! My God, come in!” he said as he stood. He automatically held out his right hand to shake mine and then realized his error. He quickly switched hands, and I clasped his with my left.

“Hello, Michael,” I said. “Good to see you.”

“Likewise, likewise. Please, please sit!”

Michael Brinkley was in his forties, fit, and not a bad looking fellow with a military cut of hair and brown eyes. He was a superb example of a CIA officer who appeared to have everything going for him. He wore no wedding ring and I didn’t know if he was once married or what, but I imagine he had no problems with the ladies. In the short time I was reporting to him last January, I knew him to be competent and driven.

Once we were sitting at the table across from each other, Brinkley’s expression displayed concern. “How are you feeling, Felix?”

I gestured with my good hand to go away. “I’m fine, Michael. Really.”

“Tough few months, eh?”

I shrugged. “You could say that. But I’m here. I can manage quite well. There may be a little less Felix than before, but I’m still the same guy with the same enthusiasm for the Agency.” I held up my hook. “This is not going to stop me, Michael. I’m more than ready to get back to work.”

Brinkley nodded and his eyes redirected to the manila folder on the table in front of him. He opened it to a bunch of typed pages with the CIA letterhead.

“We appreciate that, Felix.” He studied the words in front of him as if he were analyzing sales reports. Then he looked at me and asked, “How would you describe yourself now?”

That was an odd question. “Uh, two inches over six feet tall, straw-colored blond hair, grey eyes, keeping thin at a hundred and seventy-eight pou—”

He held up a hand. “That’s not what I meant, Felix.”

“What did you mean?”

“How do you feel? How do you evaluate your ability to do the job you were able to do seven months ago?”

“I think I just told you, Michael. I’m still the same officer with the same brain and same attitude. I’m not bitter, if that’s what you’re asking. Bad things happen. It’s the business we’re in. I’m still alive. Michael, I’m ready to get back to work. Is that what you want to hear?”

He looked down at the paper again. “You have a terrific history, Felix. You enlisted in the Marines in ’42, served in the Pacific arena, and you remained in the corps for three years after the war ended with a rank of Staff Sergeant. Why did you do that? You didn’t want to go home?”

I looked away and gave him another shrug. When I did that, my prosthetic arm involuntarily raised off the table. I’d have to watch how I moved my shoulders! “I didn’t have much of a home to go back to. My parents were already gone. The retail men’s clothing shop my father owned was sold. A sister and her family lives out west. No, Michael, the Marines became my home. I like serving my country. I thought I’d make a career of it until I got called into that meeting with the recruiter from Allen Dulles’ office.”

“Why do you think you were singled out to join the CIA?” Brinkley asked.

“I suppose I was good at analytics. I had a knack for strategy and evaluating what the enemy might have in mind. Leadership skills that maybe impressed people with ranks and pay grades higher than mine. I don’t really know, sir, I’m guessing. They never said. But I was happy to get the offer. I thought it would be interesting work, so I left the Marines and went into a different kind of government service. Michael, why are we talking about all this? You know my history.”

“Yes, yes, I do. I’m just trying to get a sense of your … disposition … now.”

“Like I said, I’m ready to get to work.”

Then Brinkley looked a bit sad. All of a sudden, I knew exactly what he was about to say, and then he went and said it.

“Felix, I’m sorry to have to tell you this, but the word has come from Washington that you can’t be an officer like before.”

I felt as if I’d been slugged in the chest. “Sir?”

“As you know, Felix, the CIA needs men in the field to be at the top of their game. With your, uhm, disability, you can’t operate at the kind of capacity as someone …”

“Someone whole?”

“Felix …”

“Michael, I’m going to the gun range every damn day. I’m practicing shooting with my left hand. I’m getting there. I get better all the time. And I’m quite mobile.”

“I’m sorry, Felix. There’s nothing I can do. They’ve made up their minds and that’s all there is to it. But hold on!” He held up a finger. “That said, we’re prepared to offer you a job in the analytics division in Washington. With your keen mind, you’d be able to study intelligence reports and analyze them, make valuable suggestions, help policymakers with their decisions, and—”

“A desk job, in other words.”

Brinkley paused a moment, smiled in acquiescence, and nodded. “It would be a really nice desk job, Felix.”

“I like it here in New York now. I’m not sure I want to go back to D.C. And I sure as hell don’t want to be sitting behind a desk, day in and day out, looking out a window.”

Brinkley leaned back in the chair and studied me. After a pause, he sighed.

I blurted, “What? Is that final? I have no say in the matter?”

“I’m afraid so. You know, I had a feeling this was how you’d react. If you don’t take the transfer, I am authorized to give you a very reasonable severance package. I made sure it takes into account your, uhm, pain and suffering.”

“Well, thanks, I guess.”

“Don’t kill the messenger, Felix.”

Actually, I was seething inside. “Oh, I’m not upset with you, Michael. Just with the bureaucrats and the upper brass.”

“Felix, I’m going to mark you down as a possibility for the Reserves. Those are former operatives who are called into duty in case of a crisis or—”

“I know what they are. I’d appreciate that.”

“I can’t promise anything on that. They may say no.”

“I understand.”

He uncovered a white envelope that had been underneath the papers in the folder. He slid it across the table to me. “That has the details of your generous severance. Taxes are already taken out.” He shook his head. “It’s unbelievable how the IRS doesn’t discriminate. You’d think CIA employees could get some kind of break, but no.” I detected some history of bitterness there, but I said nothing. “Anyway,” he continued, “it should be enough to hold you for a few months until you land on your … uhm, until you get your bearings.”

“I’ll be okay, Michael,” I said, not bothering to open the envelope. “I have a little nest egg inheritance from my family. And I’ve been saving money. I’m not a big spender.”

“I understand you like to buy cars.”

“Well, some men are golfers, others are mountain climbers. I like to buy a car and drive it for a year and then trade it in for a new one.”

“That’s an expensive hobby.”

“So are women.”

That made Brinkley laugh. “What are you driving now?”

“A 1951 Packard 250 Mayfair.” I held up my hook. “I got it cheap in D.C. before I moved here. Glad I didn’t drive that one to Florida last January. I’ve already learned to operate a shift in the steering column. Just need a little more practice. I’m in the market for something with a little more oompf, though.”

I started to stand and he held up a hand.

“Wait a second, Felix … Have you ever thought about private detective work?”

That stopped me in my tracks. “No, I haven’t. But now that you say it, I like the sound of it. Why?”

“Hang on a second. Don’t move.” He stood and went out of the room. I heard him talking to Marion for a moment, and then he came back with a piece of paper he had scribbled on and gave it to me. Printed in bold letters was the name PINKERTON, followed by an address on Nassau Street and a phone number.

“Pinkerton’s Detective Agency?” I asked. “Really?”

“They’re national. They’ve been around a long time.”

“Aren’t they based in Chicago?”

“Yes. But they have an office here and it’s huge. Big building down by City Hall. There are rumors that Robert Pinkerton II—he’s the boss now—is going to move the national headquarters to Manhattan by the end of the decade. I know Robert personally and can give you a recommendation. Think about it.”

A thousand voices went through my head, but the loudest one was proclaiming that I was now a free man. I didn’t have to answer to the government anymore.

I answered, “I will,” and put the paper in my jacket pocket. I stood and held out my left hand. “Thank you, Michael.”

He gave me a firm handshake. “Stay in touch, Felix. I hope we’ll stay friends. Let’s have lunch sometime.”

“Okay, but you’re buying!”

*

Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency was established way back in the mid-1800s by Robert Pinkerton. I knew of many of the organization’s exploits. In “olden times” they did a lot to protect stagecoaches from robberies, they hunted Butch Cassidy and his Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, tracked Jesse James, and, as the world moved into the 20th Century, were contracted by the U.S. government to break union strikes and labor organizers. That latter stuff, I know, didn’t do much for the Pinkerton reputation. They had to rebrand a bit, but there’s no question that the company had done very well for themselves. There are offices in many major cities and the one down on Nassau Street in Manhattan is nothing to sneeze at. I can get there from my Village apartment by walking southeast on Greenwich Avenue to Seventh Avenue and descending into hot subway Hades at Christopher Street, to take the IRT downtown all the way to the stop just west of City Hall. A walk east across the park and I’m there. Takes twenty minutes if the trains are operating properly. A bus works, too, but that’s much slower.

I took over a week to ponder my buddy Michael Brinkley’s advice. Was being a private eye something I wanted to do? Hell, I didn’t know. To help me consider the pros and cons, I spent a few evenings in Pete’s Tavern—easily one of my favorite dives, located in the Gramercy Park neighborhood just northeast of Greenwich Village—and sampled many a martini, alternating with highballs of bourbon and branch. Of course, it wasn’t real branch water, it was likely just from the tap. Real branch water comes from high up a natural stream in Kentucky, where the water filters through underground limestone. I’ve had maple water substituted for branch water in joints that carry it—that’s pasteurized sap from maple trees—and it isn’t bad at all.

It soon became clear that if I wanted to work in law enforcement of any kind, at least talking to Pinkerton’s was a good idea. What the hell else was I going to do? Be a doorman at a hotel? Sell insurance? Go into retail like my old man? No, thanks.

I called the number Brinkley gave me. Before I knew it, I had an interview set up on August 13. Apparently, Brinkley’s recommendation had done the trick.

Robert Pinkerton II conducted the meeting himself. He’s the first Robert Pinkerton’s grandson, a tall and somewhat big, heavy guy in his fifties. Quite a commanding presence and serious in temperament. He sat behind a large oak desk in an office that resembled an English gentleman’s library. Leather chairs, oak and almond wood paneling, table lamps with broad lampshades, and numerous books on shelves. Behind him on the wall hung an abundance of photographs depicting the agency’s achievements, portraits of his grandfather with politicians of yore, and a framed banner that read, The Eye That Never Sleeps. The place had a pungent but not unpleasant odor of sweet tobacco.

We talked about my background and he seemed impressed. He liked the fact that I was a Marine for seven years and was in the CIA until The Mishap. He offered me a cigarette out of a silver case with a big “P” engraved on it. They were all Lucky Strikes—not my favorite—but I took one, and he stood and lit it for me. He then picked up a Holmesian Meerschaum pipe—yes, of course he did—and fired it up. Obviously, this was the source of the room’s smell!

“Mr. Leiter,” he said, “I don’t know if you are aware of what we do at Pinkerton’s these days, but it’s not like what you might see in the movies. Our detectives are not Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe. We don’t do a lot of criminal investigation anymore—some, certainly—but it’s not our main focus. You see, the FBI has become larger and stronger over the past twenty years or so, and they handle that kind of thing—what we used to do before the public even knew J. Edgar Hoover’s name.”

“Doesn’t matter to me,” I said. “I can do some door-bashing, tail wayward husbands … whatever you need.”

“We don’t take adultery and divorce cases anymore. We find that stuff too seedy. We mostly do private protection services and security work. Our new guys start off doing night jobs at warehouses and hotels. You know, ‘night watchman’ scenarios. Sometimes you get assigned to bodyguard VIPs.” He nodded at my prosthesis. “Can you be an effective bodyguard with that?”

“I don’t see why not.” I raised the hook. “Mr. Pinkerton, I may be missing my right arm, but this thing is strong. But again, I should emphasize my experience in the CIA. I’m good at spotting criminals and figuring out what they’re up to. I have a mind for detail.”

“I don’t doubt it. Let me ask you this—do you know anything about horse racing?”

“I’ve seen some. I may be a Texan, but I don’t know anything about horses. I grew up in the city, in Dallas.”

“Doesn’t matter. We will eventually need someone to be on our Race Gang squad that investigates crooked horse racing. You’d shadow two other detectives to learn the ropes and you’d go up to Saratoga Springs often. Does that interest you?”

“Sure, if that’s what you need.”

Pinkerton wrote something on a pad of paper, saying, “Well, let’s see how you do with the entry level stuff.” He then nodded at my good arm. “How are you with a gun now?”

“I go to a range almost every day to practice. I’m teaching myself to be a lefty. It’s only been a couple of months.”

He nodded and then rubbed his chin as he looked at me. Didn’t say anything. That made me a bit self-conscious, but I let him stare. Finally, he said, “Mr. Leiter, I think you have some interesting qualities that could be an asset to Pinkerton’s. You don’t really fit the type of man we usually employ, given your disabilities. However, your situation just might be the kind of cover you need in being a private investigator. I don’t believe criminals would suspect that a man with a hook and wooden leg could possibly be a detective. That, combined with your law enforcement experience, I feel makes you an ideal candidate for us. What do you say?”

I gave him one of my “boyish grins” that so many people tell me I present. I’ve never thought of my face as “boyish,” seeing that I’m not fourteen anymore, but if my boyish grin gets me places, then I’m going to use it.

“Would I have to come here every day? Work in an office?” I asked.

“Depends on what jobs you’re doing. We do have investigators that work out of their homes. Freelance, so to speak. On the payroll, but they’re paid only when they’re on assignments. The Race Gang would be a regular salaried position. You would start out with some freelance spots, though. There are temporary offices in the building you’d be able to use if you need to interview clients and such.”

“I think that would suit me fine, Mr. Pinkerton. Let’s see how it goes. Then we can talk about the Race Gang after I get the hang of this kind of work.”

“The starting spots will be security and night guard jobs. Could be boring and tedious.”

I gave him that grin again. “I’m a light sleeper.”

The man stood and, wisely, held out his left hand to me. “Well, we’re the ‘Eye that Never Sleeps.’ Welcome to Pinkerton’s, Mr. Leiter.”

“The hook and the eye,” I added, gripping his palm and sealing the deal.

4

August 14–September 2, 1952

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

I spent the rest of August continuing therapy at a veterans facility in Greenwich Village and practicing shooting with my left hand at a gun range located at the New York City Police Headquarters on Centre Street near the area they call “Little Italy.” You might ask how I’m entitled to use the police range and how I can maintain a license to carry. First, let me explain that when I was still with the CIA, officers technically weren’t allowed to carry concealed weapons within the United States. However, certain palms could grease other palms under the table and I managed to obtain a permit that was good in D.C. and in New York state. When I became a civilian after The Mishap, my federal credentials greased the way in very strict New York City for me to keep my license, albeit with many restrictions. But the name Pinkerton opens doors. The detective agency had a special relationship with the police department and exceptions could be made on a case-by-case basis. Given my CIA history, my disability, and my current employment as a private investigator, somehow enough influence and favors were exchanged to allow my license to remain. I owed that to the standing of my boss, Mr. Pinkerton. His sway extended to the fellas who ran the gun range at the Centre Street building.

Yeah, the other officers practicing at the range stared at me. They wondered what I was doing there. I was sure they quietly made jokes about me because I heard some snickering. Yuck it up, fellas. Learning to ignore gawkers was part of the recovery process.

Unfortunately, at that time my aim was still terrible. I wasn’t hitting bullseyes, I was shooting bull’s tails. Whatcha gonna do? Keep practicing!