8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

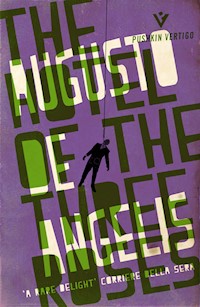

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

The shady Hotel of the Three Roses is home to an assortment of drunks and degenerates. Inspector De Vincenzi receives an anonymous letter, warning him of an imminent outrage at the guest house, and shortly after a macabre discovery is made--a body is found hanging in the hotel's stairwell. As De Vincenzi investigates, more deaths follow, until he finally uncovers a gothic and grotesque story linking the Three Rose's unhappy residents to each other.This intensely dramatic mystery from the father of the Italian crime novel, Augusto de Angelis, features his most famous creation - Inspector De Vincenzi.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Whose dark or troubled mind will you step into next? Detective or assassin, victim or accomplice? Can you tell reality from delusion, truth from deception, when you’re spinning in the whirl of a thriller or trapped in the grip of an unsolvable mystery? You can’t trust your senses and you can’t trust anyone: you’re in the hands of the undisputed masters of crime fiction.

Writers of some of the greatest thrillers and mysteries on earth, who inspired those who followed. Writers whose talents range far and wide—a mathematics genius, a cultural icon, a master of enigma, a legendary dream team. Their books are found on shelves in houses throughout their home countries—from Asia to Europe, and everywhere in between. Timeless books that have been devoured, adored and handed down through the decades. Iconic books that have inspired films, and demand to be read and read again.

So step inside a dizzying world of criminal masterminds with Pushkin Vertigo. The only trouble you might have is leaving them behind.

Contents

1

The rain was coming down in long threads that looked silvery in the glare of the headlamps. A fog, diffuse and smoky, needled the face. An unbroken line of umbrellas bobbed along the pavements. Motor cars in the middle of the road, a few carriages, trams full. At six in the afternoon, Milan was thick with darkness in these first days of December.

Three women darted hurriedly, as if driven by gusts, breaking the lines of pedestrians wherever they could. All three were dressed in black, the fashion at the start of the war, and their little gauze hats were studded with pearls. They wore string half-gloves, and all of them gripped the handles of their umbrellas in the same way, with the bony fingers of their right hands, as if threatening someone with a club. Their profiles were beaked, their eyes bright and alert, and with those chins and noses they seemed to be cleaving the crowd and the heavy mist of fog and rain. How old they were was anyone’s guess. Age had fossilized their bodies, and each was so similar to the others that without the colourful hat ribbons under their chins—mauve, claret, black—a person might have thought he was hallucinating, convinced he was seeing the same woman three times in a row.

They climbed up via Ponte Vetero from via dell’Orso, and when they came to the end of the lit pavement they plunged into the shadows of Piazza del Carmine. They instantly breathed a sigh of relief; until then, they’d had to battle through the crowd in single file, and here they found themselves more or less alone, with all the space they needed to trot along towards the church. When they reached the little door the first one pushed it, and they disappeared within.

The man who was following them and who had avoided catching up with them when they were in the piazza now came to a halt in the rain in front of the church. He seemed put out, and stared at the little black door. He passed through the short columns that closed off the porch; the chains were no longer there, only the rings that had once held them. With some difficulty, he unbuttoned his yellow raincoat with one hand and took out his watch. He had to huddle under the glow of the street lamp to see the time. Then he went up to the porch doors and hid there. He closed his umbrella.

He waited, staring at the small church door the whole time. Every now and again a black shadow would cross the piazza and disappear behind the church doors. The fog grew thicker. Half an hour went by, more. The man seemed resigned. He was tall and large, with a smooth, ruddy face under his bowler hat. His eyes were a watery blue-green, his mouth fleshy and sensual. He had propped his umbrella against the wall to dry and was rubbing his hands together with a slow, rhythmic motion which accompanied his interior monologue. He must have reached a conclusion because he suddenly clapped his hands together, as if putting a full stop to a sentence. He turned to look at his watch: 6.38. He grabbed his umbrella, opened it and ran from the porch without once glancing back at the church. It actually seemed as if he was fleeing for fear that the three women in black would come out and see him—the same ones he’d followed there only a short while before.

He entered via Mercato from Piazza del Carmine and then turned into via Pontaccio. Finding himself in front of a huge glass door that led into a vast lobby, all lit up, he opened it and went in. THE HOTEL OF THE THREE ROSES could be read on the glass door in large letters, and behind the glass hung a menu.

Inside the lobby, the man looked like someone who feels at home. He left his umbrella in a large, shiny brass stand near the door, pushed his hat back on his head and went to sit on a wicker sofa in the far corner, under a standard lamp with a large rose-coloured lampshade. He crossed his legs and cordially declared, “Foul weather, Signora Maria. I’ll bet the radiators in here are cold.”

Maria held court at a desk behind an opaque glass partition that divided the lobby from the dining room and from the corridor leading to the kitchen. She sat there, matronly, already too fat but still hale and hearty, with smooth, firm flesh of a uniform pearly whiteness. She was wearily doodling lines and circles on a piece of paper in front of her, absorbed in some thought—or maybe none. She’d noticed her guest come in and hadn’t even bothered to raise her blond head.

“Mario has just gone out to refill the boiler,” she said in a hushed, somewhat croaky voice, studiously continuing her doodling.

The man let out a grunt of satisfaction. Then there was silence. All at once he heard a stirring behind the long counter in the dining room.

“Has Mario come back?”

“At your service, Signor Da Como. Here I am.”

“An aperitivo…”

When he saw the glass in front of him on the wicker table he drank it down in one gulp, clicking his tongue. And then, again, silence. The man drummed his fingers on the table. He stood and went over to warm up by the radiator. Took a few steps, got as far as the stairs and turned back. He hesitated. He put his hands on his stomach, tucking his thumbs into the little pockets of his waistcoat and then stuffing them into his trouser pockets. His hat had fallen back towards his neck even further, to form a sort of halo around his flushed face.

He finally made up his mind and went to lean on his elbows at the manageress’s desk. The room was already dark, and only one lamp shone over the front desk. Maria was glued to the counter, where Mario was setting out plates of cold roast, marinated eel and fruit, and also one with prosciutto, salami and mortadella. She barely even seemed to notice him.

“Signora Maria…”

“Mmmm…”

“What time does Signor Virgilio return?”

“The usual time. Why?”

The man went quiet. He put his finger on the white paper, running over the lines and circles as if trying to feel their outlines in relief, for the sake of doing something and to pull himself together. He was embarrassed. He looked up at the woman but his eyes fell to her white neck, its skin so smooth and firm it seemed to lack pores.

“I wanted to ask Virgilio something. But in any case it’s the same whether I ask you or him.”

“What?”

“I need the usual favour. A hundred lire. I’ll pay it back tonight.”

“But you already had a hundred the other night. And you’re a month behind with the rent. And you have an outstanding bill with Monti for breakfast and lunch that would frighten you. He told me. It’s true that it’s nothing to do with me. If the waiters want to give credit, that’s their business.”

“I know. But frighten—frighten who? Not me. I’ll pay Monti’s bill too. A night goes well, and I settle everything. But I’ll pay back the loan of two hundred lire tonight for sure. The Englishman has received money. And he’ll play tonight.”

Maria’s face looked more static than ever. Only her pale lips were somewhat tense. She opened the desk drawer and took out a banknote, her copious bosom moving back as she did so.

“Here’s your hundred lire. But it’s the last you’ll get. I’ve said the same to your friend Engel. We can’t make loans! We’re not a bank.”

“Thank you. Mario, give me another aperitivo.”

Just then the glass door opened and the three women in black entered the lobby one after another. Da Como turned to look at them and put his glass down quickly. He smiled and made no hurry to approach them. This time Maria leant over the desk, saw the three women and turned towards the factotum.

“If they’d come five minutes earlier, we’d have saved a hundred lire.”

Mario hazarded a smile closer to a grimace. His frog-like mouth lent itself perfectly to that sort of look.

“I really wasn’t expecting a visit from you, dear sisters. It makes sense for me to come and see you, but you…”

Da Como spoke with his hands in his pockets. An unlit cigarette, stuck between his lips as soon as he’d seen them, hung from one side of his mouth and his tone was ironic, almost mocking—as it surely wouldn’t have been had he stopped them in Piazza del Carmine, when they were going to vespers and he’d lingered in the rain.

“Naturally! Your coming to see us is perfectly understandable, Carlo. We have a respectable house, we do. And whenever you come, of course, it’s always to ask us for something.” The first sister, perhaps the eldest of them, spoke. Her claret-coloured hat ribbons trembled under her chin as she uttered those words, though her bloodless lips barely moved.

“And why else should I go there, Adalgisa?”

All four stood near the glass door, the three sisters aligned in front of the man, his hands in his pockets and the cigarette dangling from his lips. Mauve Ribbons shifted, but no sound issued from the mouth of the second sister, who must have been forcibly restraining herself; her eyes were fiery. The last one, however, had a strangely gentle, imploring look, and the corners of her mouth contracted to create two deep furrows, so that she appeared on the verge of tears.

“Carlo,” she whispered so softly that her brother could barely hear. He started.

“Well then?”

“We must speak to you,” Adalgisa said, as she looked around in disgust.

“Will you sit down?”

“Here?” Mauve Ribbons now spoke and her screechy voice, quivering more in indignation than surprise, rose shrilly above the pitch of the others.

Da Como looked around in turn.

“Yes, here. Where else? You wouldn’t want me to take you to my room.” He laughed and took the cigarette from his mouth. “Everyone thinks this hotel has only one floor. But there’s a little door there, to the right of that landing”—he pointed to the stairs—“and if you open it, you’ll see a little stairway like one in a bell-tower. I go to the top to get to my little room… a garret… There are four or five little rooms up there. One for me, one for Engel and the others for the maids and the kitchen boy. It would hardly do for me to receive you in my luxurious apartment, dear sisters.”

Adalgisa turned to the other two. Mauve Ribbons pursed her lips, holding back the most biting contempt. Black Ribbons looked ever more imploring, and it was on her that the first sister’s eyes fastened.

“It’s for Jolanda,” she affirmed. “So listen to us, Carlo. We can speak to you just here. Manfredo…”

Da Como smiled, a look of triumph flashing through his eyes. He turned to the imploring sister.

“How is your son, Jolanda?”

She answered quickly. “He’s well, Carlo. He’s a good boy. He loves you.”

“Really? I believe you, even though I’ve never noticed it. Is that so?”

“Definitely. Manfredo is about to take a wife…”

“Ah!”

“We need to set him up. It’s necessary—”

“Naturally! You’d like to give them the Comerio property. Ideal! He could really make something of it. But given that the property is mine… the only thing of mine I haven’t already sold… So you’re here on an errand.”

“Carlo.”

“It’s not an errand. We’re your sisters. The Comerio property has been mortgaged twice. We’re doing you a favour to ask, since otherwise you’ll be losing it all the same, forced to hand it over to your creditors. We’ll pay off the mortgages and we’ll offer you…”

Da Como gloated even more. He rocked on his feet, his solid body swaying.

“So! You’re offering…”

“Five thousand lire.”

“Ah!”

“It’s a lot. It’s too much. But Jolanda wanted to give you as much as possible.”

“Dear Jolanda.”

“You know, Carlo, Manfredo would so like to have that bit of land.”

“Of course, of course! Five thousand! You don’t want to sit down, eh?”

“So you accept?”

“No. I refuse. The Comerio property is still mine and I’m keeping it.”

The three women started.

“Carlo,” Black Ribbons was pleading. But the ribbons on the other two trembled with contained rage.

There was a silence.

“May I offer you a little grappa?”

“We’re leaving!” Adalgisa commanded and, taking the other two by the arm, she pushed them towards the door.

Da Como hurried to open it.

“Goodbye, dear sisters!”

They were in the middle of the entrance hall and had almost reached the street. They opened their umbrellas.

“You wouldn’t have a hundred lire to lend me, would you?”

He laughed, shut the door once more and turned to Maria.

“If you only knew…”

“What?”

“They wanted to give me five thousand lire!”

“And you refused them,” scoffed the manageress.

“Exactly. They asked me to sell them the Comerio property.”

“Ah! You’re serious?”

“Of course.”

“And the property is worth more than their offer?”

“No. With two mortgages to pay off, it’s worth less. But I refused just to spite them.” He paused. “Haven’t I ever told you, Signora Maria, that I hate my sisters?” His voice was smooth as he lit his cigarette.

The three women in black walked silently through the rain. The glass door of The Hotel of the Three Roses began to swing on its hinges, back and forth, back and forth, as guests returned for their meals. Maria slowly swivelled round in her chair and switched on the lights in the lobby and the dining room.

2

After nine at night, all the tables in the dining room at The Hotel of the Three Roses were covered with green baize. Once meals had been served, the chief concern of the two waiters was to remove the tablecloths. Bottles of wine and glasses remained on some tables. The guests themselves helped to clear up. Everyone was overcome by a sort of frenzy, and they gambled in there as if it were forced labour. Many remembered and recounted with pleasure how the four most tenacious scopone players—Verdulli, Agresti, Pizzoni and Pico—had once sat at the table, cards in hand, nourishing themselves on eggs and cognac for two days and two nights.

And at nine that evening, the 5th of December 1919, Carlo Da Como began to shift around on his bed, where he’d thrown himself completely clothed just after the meeting with his sisters. It was as though the addictive excitement were seeping through the old walls and up to the top floor of the hotel to wake him. He stirred his limbs and, leaning out of bed, felt around for the light switch and flicked it on. A weak, pinkish glow like that of ten electric candles. Just enough, in any case, to reveal the meanness of that room, a garret with rooftop views. A small iron bed, a chest of drawers with a mirror, a washbasin standing on a pedestal, an enamel jug, a couple of chairs. But there was a yellow leather trunk and a suitcase of pigskin. And on the walls, three large colour prints by Vernet. Authentic ones which, with their galloping horses and flying jockeys, were alone worth everything else illuminated by the dusty lamp. The trunk, the suitcase and three prints were all Da Como had brought back with him from London. Remains of a shipwreck—his shipwreck. Apart, of course, from the heavily mortgaged Comerio property.

He smiled. The old girls wanted it to give to Manfredo. Poor Jolanda. Her eyes had pleaded and her voice had whined as she asked him to agree, because it would have been her little boy’s greatest joy to possess that property. He’d said no with pleasure. Doing wrong for its own sake made him happy.

He got out of bed and splashed his hands and face with water. He looked at himself in the mirror as he slowly dried off. He wasn’t hungry. He would go down now and have Monti give him two prosciutto sandwiches and a glass of beer. If the group were already waiting for him to play piquet, he’d eat while he played.

The group were Engel and Captain Lontario. Every evening, the three of them played piquet from nine until midnight. They kept track of their points in a notebook and at the end of the month they settled up. It was also how Da Como and Engel played when they hadn’t a cent in their pockets, and at the month’s end, for good or ill, someone took care of it. So there were several months when the captain bore the cost. At 1 a.m., when the piquet, scopone and poker were over and the door of the hotel was shut for the night, those who remained got ready for something much more aggressive. They started playing seriously.

Da Como continued studying himself in the mirror. Though he was fifty he hardly looked it; his plump body and his fresh, rosy skin were enough to inspire a young man’s envy. But inside he felt tired and worn out. The life he’d led had inevitably taken its toll. Listening closely, he could hear the wheels creaking in his brain and heart. That morning he’d bumped into Doctor Campi, who’d been a student with him in London, and the jolly doctor had cried, “Hello! How’s that heart of yours?” But maybe it had been his little joke. Of questionable taste, however, that joke.

He pulled himself together, went to the door and turned off the light—those two switches, one at the entrance, the other beside the bed, were a luxury he’d arranged for himself. He walked into the narrow corridor, which immediately turned a corner. The light from the lamp there, which reached both parts of the corridor, was even weaker than that in his room—and pinker. In that dim light he stopped in front of the closed door to the other little room, which shared a wall with his and opened onto the landing.

“Vilfredo!” he called, and then more quietly, “Engel! Engel!”

When the ensuing silence reassured him that the room was empty, he turned to glance at the other two doors opposite, beyond the stairway, where the kitchen boy and two maids slept. They were closed, of course. He hesitated before going to rap on them. There too: silence. So he turned towards Engel’s door, and warily—his every move was stealthy, and he took infinite care to prevent the hinges from squeaking—opened it. He entered the dark room, closing the door behind him. He remained there no more than a few minutes, and when he left a sarcastic smile was creeping over his lips. He started down the stairs, whistling softly.

When he came to the last step before reaching the main staircase—the small stairway that led to the attic rooms joined up with the larger one on one side by way of a small door, which to anyone unaware of the hiding places in that old house seemed only to lead to another room off the first large landing—Da Como took his hand out of his pocket to adjust his tie. Then he stepped onto the brightly lit main staircase and started his descent. The rear part of the building had only one floor, so there were only two flights. From below came the distant hum of the card-players, the sound of bottles and glasses and the audible voices of one or two people in the entrance hall.

Da Como stopped and looked up. A slight woman was coming down from the guest rooms dressed in black and draped with a heavy widow’s veil, her golden hair flaming out from beneath a black crêpe hat. Her face was pale, but lit by two enormous eyes with wide blue irises. Her lips were such a bright coral they looked like a gash. Da Como waited for her to go by before resuming his descent, and continued to observe her. The woman did not notice him and moved slowly, looking straight ahead, her face calm and those two bloody lips half open as if in a smile.

“Where the devil has this one come from?” murmured Da Como, and he kept behind her as he descended.

The widow crossed the lobby with the same robotic steps. When she got to the lounge, she spotted an empty table near the arch by the door and went to sit at it. Now she kept her eyes lowered, seemingly unaware of the curiosity she’d aroused. Monti immediately headed towards her, his eyes sparkling more maliciously than ever, his ears keen and straining, an obsequious smile on his lips.

“Is it still possible to eat?”

“But of course. Anything the signora desires.”

The signora nodded yes to everything they offered her, refusing only the wine and asking for mineral water instead. Monti started for the kitchen, but as he passed the front desk he stopped.

“Room number?”

“Twelve,” said Maria.

Monti grabbed a register and quickly consulted it. He read: Mary Alton Vendramini.

“She’s foreign?”

“What does it matter to you?”

“Single?”

“Yes. Ooph! What a nosy parker!”

The waiter disappeared down the short corridor towards the kitchen. The card-players immediately went back to work.

“Pass.”

“Chip.”

“A terza reale and three aces,” Engel’s deep voice announced. He was as large and heavy as an elephant.

Da Como played with a prosciutto sandwich in one hand and his cards in the other.

“It’s idiotic to put down your seven in the first round, when you could easily have got rid of your four,” Verdulli yelled, his face as red as a cockerel’s. The scopone table was the loudest. Those four seemed obsessed, and Verdulli—a theatre critic who was by nature always green with bile—seemed keenest. He was actually just the most strident because of his high-pitched voice.

There was already a body in the hotel, and not a single one of the people playing, eating or talking in those rooms knew it. Or at least no one had admitted to knowing anything. So men and women alike reacted with horrified amazement and concern when, at 10.31 precisely, the hunchback Bardi came virtually cartwheeling down the stairs, screaming in his high, cracked voice: “A man has been hanged upstairs! A man has been hanged upstairs!”

He’d actually seen him, poor Bardi. A body dangling from the last level of the stairway that led to the furnished attic rooms, to those garrets from which Da Como had come down not an hour before with that sarcastic smile on his lips. Still yelling, Stefano Bardi crossed the lobby and went into the dining room. As soon as he’d gone past Maria, sitting enthroned under the arch, he had to stop. And he would have fallen had Mario not suddenly leant across the counter and grabbed the lapel of his jacket, pulling him up like a limp puppet. As he did so, the sound of plates loaded with prosciutto and marinated eel could be heard crashing to the floor, shattering at the hunchback’s feet.

3

De Vincenzi looked up from the papers in front of him. “Sani!”

“I’m coming,” the deputy inspector responded, and straightaway his chair was heard to move.

The inspector went back to his reading: a handwritten sheet of foolscap in clear, well-formed letters such as you’d see in a primary school handwriting exercise. On the sheet was a long list of names. He started to peruse them and then stopped and picked up a smaller piece of paper, typewritten: an unsigned letter, which he slowly reread.

Sani stood waiting in front of his superior’s desk. The light from the table lamp—the only one in the head of the flying squad’s room—fell from a large green shade in a circle over the papers. The deputy inspector remained in shadow.

“Ah!” De Vincenzi raised his head. “You’re here.” He showed the letter to Sani. “Have you read it? What do you think?”

“I read it. You left it open on your table.”

“You did the right thing.” De Vincenzi smiled.

He was younger than his subordinate, but Sani deferred to him with something more than respect. Sani had had him as his immediate superior at the flying squad for only three months, and already he’d learnt to appreciate every one of his merits. Because Carlo De Vincenzi was undoubtedly a man of quality. Rather reserved, and somewhat dreamy, but that faraway air of being absorbed in something hid an exquisite sensitivity and a deep humanity. Sani understood him, and his respect derived chiefly from his friendly devotion, an unforced attachment to him.

“Well? When the chief constable gave it to me this morning, I said to myself somewhat contemptuously: an anonymous letter. But when I read it, I had a strange impression…” He stopped, then added, “It’s anonymous, and it was written by a woman.”

“How do you know?”

“Every sentence of this letter reveals an unwholesome hysteria which couldn’t possibly be a man’s. Listen.” He read slowly, stopping after every sentence:

There’s a place in Milan where people gamble furiously all night. And that’s not all: everyone who frequents the place or lives there is hiding a secret he cannot confess, one that informs all his actions, and leads to terrible things.

He looked up. “No man would have used a phrase like that. Only a woman could have written it. It’s obviously nothing but a passage from a romantic novel.”

A gathering of addicts and degenerates live at The Hotel of the Three Roses. A horrible drama is brewing, one that will blow up if the police don’t intervene in time. A young girl is about to lose her innocence. Several people’s lives are threatened. I cannot tell you more right now. But the devil is grinning from every corner of that house.

“And that’s how it ends. There’s nothing else, do you see? Just some typing on a half-sheet of paper.”

“Is it a joke?”

De Vincenzi shook his head.

“It’s not a joke. It cannot be a joke, precisely because it is ridiculous.”

“It could have been written by some crazy person.”

“Could have been, perhaps; but I’m not convinced. I tell you it’s my intuition, and nothing else. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if something happened in that hotel. So much so that I immediately asked the Garibaldi station to let me have a list of the guests actually staying at The Hotel of the Three Roses. Here it is. I received it a short time ago.”

“And what did you find there?”

Sani couldn’t conceal his scepticism. It seemed to him for the first time since he’d started working with De Vincenzi that he was wasting his time. How could anyone take a letter like that seriously?

“Their names, of course. What else would there be? Right now they don’t say a thing to me, even though the branch inspector, guessing what I might want, added all the information he could find on each individual after his or her name. There are about ten women and around twenty men, including the manager of the hotel, his family and the staff.” De Vincenzi now took the sheet of foolscap in his hands and studied it. “In any case, something is strange, and it strikes one right away. Look!” He counted quickly, running his finger down the list. “Five of the guests are from London and have been staying there for a long time. Vilfredo Engel, Carlo Da Como, Nicola Al Righetti—that one’s an American of Italian origin—and Carin Nolan, a fairly young Norwegian, not even twenty.”

“The threatened innocent,” Sani joked.

“Maybe… And another Englishman, also quite young: Douglas Layng. He’s twenty-five.”

“There’s nothing that strange, is there, about five people from abroad running into one another in the same hotel in Milan?”