6,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

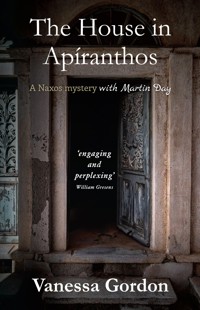

- Herausgeber: Dolman Scott Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: A Naxos mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

A body from the 1940s is found in an abandoned house in Apíranthos on Naxos. Archaeologist Martin Day is called to examine the ancient artefacts buried with it. Soon he is deeply involved, especially when more antiquities are found hidden in the old house. As he takes ferries round the Cyclades, flirts with the mystery of the Phaistos Disc, and surprises his wife with a romantic break on Santorini, the questions hanging over the unidentified skeleton are never far from his mind. He begins to work out what may have happened, though his theory is as incredible as anything he has come across before. He also realises that there are people who would rather that the secrets of the house remain just as they are: buried in the past.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 392

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Vanessa Gordon studied English literature at the University of Exeter and gained a PhD in Anglo-Irish fiction from the University of London (Bedford College) before having a career in the music industry. She has travelled all over Greece and enjoys improving her knowledge of its language, ancient history and archaeology. In addition to The Naxos Mysteries, she has published a book on the cuisine of the Cycladic islands, A Greek Feast on Naxos.

Naxos is the largest island in the Cyclades, and its tallest peak, Mount Zas, is also the highest in the Cyclades. Naxos is south of Athens, due north of Santorini and east of Paros. Inhabited since the Palaeolithic Age, it was an important site during the Bronze Age, was settled by the Mycenaeans, thrived in the Classical era, and was in the control of the Venetians for over three hundred years. The island has produced some of the finest marble in Greece since ancient times, and its famous monument, the iconic Portara, stands on an islet near the port.

Naxos is an island of contrasts. The main town, Chora, is crowned by a Venetian castle, the Kastro, around which are the labyrinthine streets of the Bourgos. Modern Chora is a popular and successful tourist resort, and the western beaches are increasingly busy, but beyond the town you will find uninhabited hills, attractive villages of white houses, quiet beaches and archaeological sites. There are imposing Venetian towers and welcoming tavernas, sought-after artists and ceramicists, soaring eagles and vultures, and precipitous mountain roads. There are feasts and festivals, spring flowers, a carnival period, musicians and dancing, and, if you know where to look, there are archaeologists.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Naxos Mysteries

The Meaning of Friday

The Search for Artemis

Black Acorns

The Disappearance of Ophelia Blue

The Reach of the Past

The House in Apíranthos

Non-fiction (with short story)

A Greek Feast on Naxos

Published by Pomeg Books 2024

Copyright © Vanessa Gordon 2024

Cover photograph and maps © Alan Gordon

This is a work of fiction. The names, characters, businesses, events and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser.

PoD - ISBN: 978-1-7393053-4-5eBook - ISBN: 978-1-7393053-5-2

Pomeg Books is an imprint ofDolman Scott Ltdwww.dolmanscott.co.uk

www.thenaxosmysteries.co.uk

To Maroula Kondyli

One of the most remarkable true stories behind The House in Apíranthos was provided by three generations of the family of the late Nikolas Peristerakis. I had the honour of meeting his daughter, Irini Papadopoulou, over cups of tea by the sea in Chora, Naxos. With us were Anastasia Peristeraki, Irini’s niece, and my friend Maroula Kondyli, Irini’s great-niece and god-daughter. Learning about Nikolas’s courage during the island’s occupation in World War 2 inspired me to create the fictional history of Mihalis, but I also pay tribute to Nikolas’s tremendous bravery in Chapter 25, where I tell his story as I heard it. I owe his family a great debt of gratitude.

For the filming scenes throughout the book I am indebted to my friend, the writer/director Brian O’Connell, on whose filmset I worked in a small way in 2023. Brian’s patient voice hovers behind the more frustrated one of Scott Macfarlane in the scenes at Phaistos, Akrotiri and Despotiko. Ben Vickers, my fictional Director of Photography, owes everything to professional cinematographer Zsolt Magyari, whom I met on Brian’s set and who has been generous with his advice during the writing of this book.

The scenes where Martin Day presents in front of the camera, though fictionalised, are based on research and my own visits to the locations, but I would like to express my admiration for and gratitude to the real archaeologists, past and present, behind these astonishing excavations.

I’m grateful to my editor Phil Williams, and to Richard Chalmers and his team at Dolman Scott, for their professional help. I would like to thank Maroula Kondyli, with whom I have had many pleasurable conversations about language, for advising me on my use of the Greek language.

The Numismatic Museum of Athens was extremely helpful while I was researching ancient coins of the Aegean, and their displays were inspirational.

D H Lawrence’s poem, ‘Snake’, to which I make reference in Chapter 27, was published in Birds, Beasts and Flowers. Poems by D H Lawrence in 1923.

I would also like to thank Robert Pitt, who first introduced me to Greece and its antiquities; Jean Polyzoides, who tirelessly supports me and The Naxos Mysteries; Suzanne and Steve Hay of Naxos and Scotland; Lena Yacoumopoulou of Paros; and of course the owners and staff of all my favourite places on Naxos, not least Diogenes Café.

My warmest thanks go to my husband Alan for his love and support, and also for his excellent photography, and to my son Alastair for our many interesting conversations about writing.

Selected Further Reading

The Lost Treasures of Troy Caroline Moorhead(Chapter 6, The Speechless Past)Prehistory Colin Renfrew (Chapter 1, The Idea of Prehistory)The Aegean of the Coins Numismatic Museum PublicationThe Mycenaean World K.A. & Diana Wardle (Chapter 4,Tombs and Burial Practices). The authors passed during thewriting of this book and are sadly missed by their friends.

More suggestions can be found onwww.thenaxosmysteries.co.uk

Nikolas Peristerakis

I was introduced to Nikolas Peristerakis’s only surviving child, his daughter Irini Papadopoulou (née Peristeraki), in May 2024, shortly after her 91st birthday. She gave her blessing to the honouring of her father’s actions in The House in Apíranthos.

Nikolas and his family lived in the Bourgos, the labyrinth of old houses just below the Kastro in Naxos’s old town, Chora. He was born in 1902 and died in 1977. His wife Anthoula (née Vintzileou) was born in the village of Komiaki, the place where a Mycenaean tholos tomb was found in the early twentieth century. They had eight children, of which Irini was the youngest. Nikolas was to be involved, without seeking such an experience, in the rescue of two survivors of a crashed Allied fighter plane.

Identifying this particular tale of rescue from the various air crashes that happened in the Cyclades is challenging, especially after such a length of time. As we understand it, Nikolas Peristerakis found two airmen on a beach north-east of Chora. He found the injured men hiding in a place called the Aga Fountain, a structure which protected a spring and was surrounded by trees, affording the men temporary shelter and drinking water. (The Aga Fountain collapsed in 1978, and only a few trees remain in the area today).

Nikolas worked out what had happened to the men despite not being able to speak English. He gave them old clothes to wear instead of their uniforms, and took them to his home. The men rested there for several weeks, recovering and hiding. Their escape from Kalados Bay was being arranged during this time, and was successfully carried out. The airmen were picked up by a British submarine and taken safely to the Middle East where they could be repatriated.

Nikolas was captured some time afterwards and submitted to torture, but he survived. His health suffered for the rest of his life as a result. It is believed that he later received a medal from Great Britain (possibly The King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom) in recognition of his bravery, but the family no longer have it. What they do have are their memories, and a great deal of justifiable pride.

Reviews of The Naxos Mysteries

Terrific stuff!

Speaking as an archaeologist who has been working on Naxos and Keros since 1994, it is all too apparent that Vanessa Gordon just gets it. Her love for Naxos shines through, and I delight in recognising so many locations. Behind every tale is a reverberation of something real, and that’s why the books work so well. Wonderful and utterly believable characters and stories.

Tristan Carter, Professor of Anthropology, McMaster University, Ontario; Director, Stelida Naxos Archaeological Project (SNAP)

Vanessa Gordon continues to capture the mystique, mythologies and mysteries of the Greek island of Naxos. The Naxos Mysteries are engaging and perplexing, a lyrical hymn to the beauty of the Greek island that figures so prominently in them. Much of the delight comes from the lovingly rendered portrait of the Cyclades: a sunset over the Aegean, the rugged yet fertile landscape, the ancient ruins and long stretches of beach, and the delightful portrayal of taverna life and cuisine.

William Gresens, Mississippi Valley Archaeology Centre, University of Wisconsin La-Crosse, USA

These books need to be read by anyone who likes meandering though the narrow streets of the Cycladic islands, and learning on the way. They are a delight to read and showcase the islands in a unique way. The author makes me feel as if I know the streets and tavernas of Naxos as well as I know them on Paros, where I have lived for over twenty years. I follow her greedily along the meandering pathways and secret kafenions where the bougainvillea hangs down in huge red bunches, reaching across to the next door bakery, until we reach a taverna with tables with checked tablecloths, friendly waiters and cooks who shout to you about the dish of the day. The books leave you with a yearning to see this island for yourself.

Jean Polyzoides of Paros, Cyclades

A NOTE ABOUT GREEK WORDS

MEN’S NAMES

When the man is spoken to directly and in some other circumstances, the ending of his name can change, often dropping the final s. Kostas/Kosta. Irregular examples include Alexandros/Alexandre. This also applies to surnames, such as Samaras/Samara.

PLACE NAMES

Chora and Halki begin with the same sound as in the Scottish ‘loch’

Oia is pronounced EE-uh

agios m./agia f. means saint

agioi is the plural of agios

Agia Triada means Holy Trinity

GREETINGS & EXPRESSIONS

Kyrie m./kyría f. are forms of address, like monsieur and madame. In Greek they are not capitalised except at the start of a sentence (except in O Kyrios meaning God)

Kyría kathigitria – Madame Professor

mou – my. It can be used as a term of affection, as in Giorgo mou

Kalimera – hello, good morning. Kalimera sas is the plural or formal version

Kalispera – good evening (Kalispera sas)

Kalinichta – goodnight

Yeia sas – hello

Parakalo – please

Adio – goodbye

Oraia/poli oraia – nice/very nice

Poli nostimo – very tasty

Malista – certainly

Ti kaneis – how are you? Ti kanete is the plural or formal form

Kala – fine, well. Poli kala - very well. Kala? - are you well?

Kala, esi? I’m well, and you?

Harika – nice to meet you

Kalos irthate – welcome

Kali orexi – bon appétit

Kala taxidia – safe travels

Stin yeia mas – good health, cheers

Panagia mou! – an explanation of shock, Holy Mary!

O Theos na ton anápavsei – God give him rest

Ti kanoun i neonymfi? – how are the newly-weds?

GENERAL

zacharoplasteio – confectionery shop

kafenion – traditional cafe

plateia – town/village square

paralia – beach, seafront

Kastro – castle

Bourgos – area right beneath the castle

astynomiko tmima – police station

tavernaki – little taverna (-aki is a diminutive)

avli – courtyard garden

kaïki – small boat (caique)

volta – evening walk

panigyri – festival, feast, fair

papas – priest

yiayia – grandmother

smyrida – emery

meraki – passionate enthusiasm

xerosfiri – drinking on an empty stomach

xromata – colours

afentiko – boss, manager

archaiodifis – antiquary

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TERMS

kouros (plural kouroi) – ancient sculpture of a nude male youth

thyrsos – ceremonial wand or staff

rhyton – a drinking or pouring vessel, often shaped like an animal head

dromos – a ceremonial walkway into a temple or tomb

stele (pronounced stEE-ly) - a monumental slab/marker/ headstone. Plural (same pronunciation) stelai

chiton – a tunic

himation – a mantle or wrap

akroteria – architectural ornaments at the corner or edge of a roof

FOOD & DRINK

Kitron – a Naxian liqueur made from kitron fruit

misokilo – half kilo: wine is measured by weight in Greece

kokkino krasi – red wine

koulourakia – Greek biscuits (from kouloura, a coil)

dakos – a rusk used in a salad, especially in Crete

koukouvagies – owls

fava – a yellow split-pea dip

raki – a clear liquor made from grapes

rigani – a Greek type of oregano

patates tyganites – fried potatoes, chips

pantzarosalata – beetroot salad

lavraki – sea bass

ladolemono – olive oil and lemon (lado, oil)

tirokroketes – cheese croquettes (tiro, cheese)

apaki – delicate smoked pork, Cretan

stamnagathi – wild greens (horta) of Crete

gopa (plural gopes) – a small fish in the sea bream family

oximelo – a sauce made with honey in Crete

kapriko – a dish made with belly pork in Crete

staka – a sauce made from clarified butter, Cretan

kleftiko – a traditional Greek lamb dish

mastiha – a liquor made with mastic from Chios

myzithra – a soft, white, creamy, sour cheese (sheep/goat)

kefalotyri – a hard tasty Greek cheese

chlorotyri – a special cheese from Santorini

Prehistory is the period of human history before the invention of writing. The British historian Sir Francis Palgrave called it ‘the speechless past’.

As recently as the eighteenth century, it was believed that we would never be able to discover the truth about this apparently lost era. With no written records, on stone, papyrus, or paper, it seemed that such knowledge would be beyond human reach forever.

With developments in science in the nineteenth century, including our growing understanding of evolution, the presumed origin of the human species was pushed back thousands of years. The new discipline of archaeology came into existence, and with it the secrets of prehistory began to be understood.

Most of it lies buried beneath the ground.

1

February 1944, Naxos

The house in the centre of Apíranthos had lain empty for several decades. Abandoned when its owners left the island in 1930, it had become a convenient place to leave the rubbish that was otherwise hard to dispose of. It had been left to crumble, like other old buildings in the village, because renovation in the steep lanes that climbed the sides of Mount Fanari was costly and difficult.

One of a row of terraced houses in the style known as ‘traditional’, the house had once been grand, with a first-floor balcony and three fine doors to the street. Only inside did the extent of its downfall become clear. Its decline had been hastened with the addition of unwanted sacks of solidified cement, half-used bags of sand, rusty canisters of used engine oil, broken ladders and old roof joists. The place smelt of damp and decay.

Yet the three men inside the house were not there to dump waste. It was still dark, long before the village woke. One of the men had been in the house all night, digging the hole. The other two had just arrived: an older man and a boy with a wheelbarrow. As they closed the double door to the street behind them, they were relieved that they had not been seen.

The body in the wheelbarrow was curled in the foetal position and wrapped in a sheet. The worst part had been stripping him naked as soon as he was dead. One of the women had done this, and the Pappas had taken the clothes and dropped them down a well on the outskirts of the village. They had turned the dead man on his side and drawn up his legs before rigor mortis set in.

Dino, the man who had been digging, heard the soft close of the front door. He came cautiously into the front room, out of breath from climbing the spiral staircase from the cellar. He flicked his torch briefly towards the faces of his friends, then down to the barrow. He extinguished it quickly; the only remaining light was a faint glow from the descending stairwell.

‘Were you seen?’ he whispered.

‘No.’

‘Thank God!’

He attempted a smile, mostly to reassure himself. His hands and face were filthy, and he wiped his forehead with his handkerchief.

‘Do you think we’ll be able to get him down there?’ he asked, sounding doubtful.

He was worried that after all this effort, all this risk, they would not be able to manoeuvre the rigid body down the tightly twisting steps. When he had arrived last night, alone and frightened, the stairwell had seemed impossibly narrow.

The older man, known as ‘the Uncle’ out of respect because he was their leader, shone his own torch down the steps. It would not be easy.

‘We have no choice, Dino. You go first and steady us as we come down. We don’t want to drop him.’

‘Panagia mou!’ muttered Dino, turning away to do what he was told and adding a few intercessory prayers.

The Uncle and the boy, Giorgos, braced themselves to lift the corpse. Thin and broken though he was, the dead man was still heavy and awkward to carry. One of the women had sewn up the sheet in which he was wrapped, so at least they did not have to see him or worry that he would fall out as they heaved him down to the cellar.

‘Ready, Giorgo?’ said the Uncle.

As they lifted the dead weight between them, the wooden barrow clattered onto its side; the lad cried out, jolted by shock.

‘Get a grip, boy.’

The Uncle spoke urgently but not unkindly, in the old Cretan dialect of Apíranthos. They needed to hold tight, both to the body and to their emotions.

‘It’ll soon be over,’ he added in an undertone.

They carried the remains of the man they had liked and respected to the opening of the stairwell. The Uncle turned to take the more difficult position of going down backwards. He felt the supportive hands of Dino on his back, and was grateful for them as the whole weight of the body was transferred to him. They manoeuvred down the spiral staircase with care and managed to reach the cellar without an undignified fall.

Dino had dug the hole, or grave, in the hard earth at the furthest end of the room, near a hearth that had once been used by the servants. Around the pile of earth was the detritus of generations: a pile of unwanted pots, some large terracotta urns, a broken chair, an old pram with a missing wheel, all covered in dust and spider webs.

Giorgos jumped when he heard a rat scampering somewhere in a dark corner of the room. The whole basement was full of junk, and he was ashamed to be consigning the dead man to such a filthy and undignified resting place. Unlike the Uncle, who was murmuring a prayer, he could find no strength to utter one.

The shrouded body slipped from their grasp as they lowered it into the shallow hole, causing part of the side wall to crumble over it. In the light of the small torch that Dino had propped on a shelf, they drew back and struggled to regain their composure. The Uncle spoke more words over the dead man, and they stood with hands clasped and heads bowed until he had finished.

‘You have it, Dino?’ the Uncle said quietly.

Dino nodded; he had brought the bag with him the night before. It might have passed for a small bag of food if he’d been stopped, but mercifully no one had seen him. He knelt on the edge of the grave and placed the bag, unopened, in the place on the shrouded shape where the dead man’s hands would be. He shuddered and stood up again, backing away respectfully, muttering another prayer for the intercession of his favourite saint.

Reluctantly, as had been agreed, they took turns to refill the grave using Dino’s shovel. That done, they firmed the earth by stamping on it and carried items from across the room to cover the area: broken paving stones, discarded bricks, a small millstone from the original hearth which took two of them to lift. They topped this with a sturdy wooden table and propped an old door on top of that, leaning against the wall.

‘That will have to do,’ muttered the Uncle. ‘Let’s hope it’s good enough.’

‘Adio,’ said Giorgos, his eyes on the dead man’s resting place. ‘Adio, kyrie Mihali.’

‘O Theós na ton anápavsei,’ said the Uncle. May God give him peace.

Dino patted the boy’s arm reassuringly. He leaned his shovel against the wall next to a broken pitchfork, preferring to lose it than be seen carrying it out of there. Then he took the torch down from the shelf, creating a shadow-play of pots, tables and bizarre shapes that raced around the cellar, and made for the staircase.

The others followed. And so they left the dead man to his endless rest in that empty house, and each one of them dealt with his horror as best he could as they made their way to their separate homes.

2

Naxos

Archaeologist and film presenter Martin Day unfolded himself from the cramped interior of his old Fiat 500 and reached inside the back for his briefcase. Naxos was busy, tourism being well under way by June, and he had been lucky to find a place to park. There had been nowhere in the shade and the day was hotter than usual. He locked the car and left it to heat up to a gruelling intensity that would be all but unbearable by the time he was ready to drive home.

He was looking forward to his meeting with George. Giorgos Kostakos, who owned a travel business in the Chora of Naxos, was relieving him of the burden of booking all the ferries, flights, hotels and hire cars he would need during the coming months of filming in the islands. Normally he would make his own travel arrangements, but this summer was not going to be normal. Not in the least. He was going to be working on some of the most outstanding ancient sites in the Aegean as part of a project more challenging than any he had attempted before. It would be, as he had said to Helen only that morning, extraordinarily hard work, despite being both fun and rewarding.

Inside his friend’s cool office, Day threw himself into a chair where he could get the full benefit of the air conditioning.

Giorgos Kostakos, third in the family of that name and a pillar of the community, shook his hand from a half-standing position and sat down again behind his desk with a laugh.

‘You’re going to be a busy man, Martin,’ he said, pulling open the desk drawer and bringing out a folder which he handed to Day.

‘Now you understand why I came to you.’

‘So, everything is arranged for your first three trips, but I’m still working on the rest. Thanks for sending your wife’s driving licence details. Her arrangements are in the file too.’

‘You’re a star, George,’ said Day. ‘Any problems?’

‘Only one. I had to accept a room upgrade for the hotel on Santorini. No extra charge.’

‘Great!’

‘The trip to Crete was the most complicated, but it turned out well. You and your wife travel there on the Seajet and there’s a hire car arranged at Heraklion which either of you can drive. You take it to Phaistos and keep it for the duration of the filming. After you return to Naxos, your wife keeps the car for the rest of her time on Crete and drops it off at the airport when she leaves.’ He grinned. ‘She then flies to Santorini.’

‘Perfect,’ said Day, imagining Helen’s face when he told her that she would be flying to Santorini to join him, instead of going home alone to Naxos.

‘The Santorini hotel – is it an anniversary or something?’

‘No, just an opportunity to spoil ourselves.’

‘Well, you’re certainly doing it in style. The first few nights, while you’re filming, you’ll be staying at the Villa Fengari, together with Mr Mark Hikajo —’

‘Hijazi. Mark Hijazi.’

‘Sorry. Villa Fengari is spacious and close to where you’ll be working. I need Mr Hijazi to send me some details …’

‘No problem, I’ll remind him when I speak to him.’

‘Once the work finishes, you and your wife move to your suite at the Hotel Hephaestus in Oia: view over the caldera, complete with jacuzzi. That’s the upgrade.’

‘I owe you,’ said Day, though he had never considered the value of a jacuzzi until now.

‘For the sea crossings between Santorini and Naxos I’ve used Seajets again, because it’s the fastest way. You said you’re not a good sailor?’

‘No, not especially,’ he admitted. ‘I cope.’

‘Well, with a schedule like yours this summer you should build in some recovery time.’

‘Oh, I have, George, but most of it will be spent working on the next script.’

‘What exactly is it that you’re doing?’

‘A series for television about excavations in the Aegean, most of them still in progress and making real-time discoveries. Mark and I are writing the scripts between us, and I’m standing in front of the camera.’

‘Looks like you’ll need that jacuzzi.’

Day nodded. ‘The third trip – how far is our accommodation from the Despotiko site?’

‘Close enough. You and Mr Hijazi will stay in a hotel on Antiparos and get the local ferry across to Despotiko island each day. The whole of Antiparos is only eleven kilometres by five, probably not even that. You won’t need a car: I’ve given you the number of a couple of local taxis for whenever you don’t get a ride from your colleagues.’

‘That’s fine.’

‘The ferries are all booked for that trip too; you go from here to Paros and change to a smaller boat for Antiparos. You won’t have time to get sick.’

‘Don’t you believe it, George. Is your bill in here too?’

‘Yes, but it only covers what I’ve done so far …’

‘My agent likes to see the costs as we go along. I’ll send him the rest later. You have all the dates and details for Sifnos and Tinos?’

‘Yes, I’ve made a start on those already. Will your wife be accompanying you?’

‘Not sure yet, I’ll let you know. Well, thanks a million, George. It’s great to have your help.’

‘My pleasure, Martin. I’ll be in touch. Kala taxidia!’

***

Having said goodbye to Giorgos and plunged back into the heat of the afternoon, Day strolled along the length of the paralia for no better reason than to look at the yachts moored against the sea wall. It was a walk he always enjoyed. Some of the vessels were private and some were commercial, offering trips to remote bays or the small islands of the Lesser Cyclades. Some specialised in the ever-popular sunset cruises.

He extended his walk along the long concrete jetty that led towards the open bay of Naxos. Cars and motorbikes were parked along it, next to the vehicles of the Hellenic Coast Guard. At the far end, the local fishing boats had unloaded their catch and were restoring their nets. A fisherman checking the lifting equipment at the stern of his boat regarded Day curiously. Few people went that way without purpose, and it was clear that Day had no purpose. He walked on. At the end of the jetty there was nothing but an empty bucket left by a fisherman, and a large black duck.

Sauntering back to the paralia, he came to the small boats that belonged to the local people who loved the sea that was their heritage. These small fishing boats would have spent the winter outside their owner’s house, or on an unused piece of ground, until being brought down to the water, and had fine names such as Pegasos, Andromeda or Panagia.

He stood breathing deeply and enjoying the fresh sea air, watching the shimmering of light on the wavelets spreading before him, taking no notice of the sound of the Blue Star ferry as it prepared to depart from the port. Inevitably, then, he turned towards his favourite bar, Diogenes.

Nobody who knew him would have been surprised at this.

His way took him past the statue of Petros Protopapadakis, Naxos-born Prime Minister of Greece. The statue stood among trees and grass, surrounded by tavernas and traffic, presiding over leisure and tourism. One of the most successful examples of this was Diogenes Café-Bar.

It was sufficiently late in the afternoon, he thought, to make ordering a gin and tonic respectable. He did so without the need for words. Alexandros, the waiter who came to Naxos each year to work in the bar for the summer season, confirmed Day’s usual order with little more than a raised eyebrow and a wave.

As he looked round, awaiting his drink, Day smiled to himself. He was now on first name terms with all the staff at Diogenes and it felt like a second home. He had become part of an amorphous group of ex-pats who lived on the island, people who frequently came to Diogenes and would exchange a few words with him, either in English, Greek, German or French according to their nationality.

His favourite table faced away from the Portara, its seat in the shade. He was ideally placed to see along the wide pavement known as the Protopapathaki, looking across it to the marina. He was idly gazing out when Alexandros returned, put his drink and a bowl of nuts on the table, and nudged the bill under the empty ashtray. Having done this, he was free to shake Day’s hand.

‘Ti kaneis, Martin?’

‘Poli kala, esi?’

‘You know it, I am back in Naxos, so I am happy,’ said Alexandros, grinning. ‘Excuse me.’

He strode off towards the front of the bar. A group of pretty girls had stopped to look at the menu board. Day sipped his drink and watched as the waiter tried to encourage them inside.

There were four girls, young and full of life, who seemed to be friends on holiday together. They were laughing and joking, and discussing in Spanish the merits of the snack menu offered by Diogenes. One of the four was unimpressed, but the other three were hungry enough to find something they liked on any menu. So much his basic Spanish told Day, as he watched Alexandros enquire politely what kind of food they wanted and extol the virtues of his workplace. His behaviour towards them was respectful and modest, and even Helen, who had no time for the Greek custom of pestering passers-by, would have admired the charm and delicacy with which Alexandros was cajoling his potential customers.

Day turned his attention back to the people at the tables around him: he might perhaps find one or two of his fellow regulars. Instead of the ex-pat familiars, however, he found himself meeting the eyes of a stranger.

A Greek of about his own age, slightly on the wrong side of forty, was sitting with his chair tilted back to keep his face out of the sun, and like Day had been watching Alexandros try his magic with the girls. He wore an expensive-looking tracksuit and immaculate white trainers, and had a look about him of an academic or an artist. In front of him was a small beer, half consumed. He nodded to Day, aware that they were watching the same scene play out.

‘Good luck to him,’ he said lightly, looking towards the waiter.

‘It’s a tough life,’ murmured Day at exactly the same time.

The Greek laughed and took another drink from his glass.

A few moments later Alexandros failed in his efforts to persuade the group of girls to take a table. Perhaps if he had been less reserved, less respectful, he might have been more successful. The girls moved away along the pavement, still laughing and chattering, and one turned to look back. Alexandros, however, was already serving another table and only Day saw the look on her face.

It had been a small enough scene, but amusing. Day wondered whether, at the age of forty-one, he had become rather too nostalgic about the young and their romances, for he had interpreted the girl’s expression as one which the waiter might well have enjoyed. He lifted his gin and tonic, watched the cubes of ice push the lemon slice gently and ineffectually among the bubbles, and savoured another sip.

For a while he sat thinking through a section of his script for Crete. He was having some trouble with it. Occasionally he made a note on a piece of paper from his briefcase, losing himself in his work. Only when Alexandros came past for the fourth or fifth time did he look up and ask for a second drink.

‘Losing your touch, Alexandre?’ he teased.

The waiter only smiled and shrugged, shaking his head resignedly, before going to fulfil Day’s order at the bar. On the way he snatched up a menu and gave it to a couple who had just come in from the lane. He was back within minutes with Day’s drink and another slip of paper that joined the first beneath the ashtray.

‘It’s not the worst place in the world to work, is it?’ said Day to his new acquaintance at the next table, with a glance across to Alexandros.

The Greek nodded and finished his beer, smiling over the rim. He took his chance to ask for another as a different waiter passed his table.

‘British?’ he asked companionably. ‘But you live on Naxos? They seem to know you here.’

‘Yes, I come to this bar often when I’m in town. I live out in one of the villages. You?’

‘I’m in the process of moving to Naxos. New job. I start on Monday. Which village?’

‘A place in the hills called Filoti. It suits us, it’s less busy. Where will you be living?’

‘Probably around here. I’ve been talking to house agencies today. That’s why I need a beer.’

Day grinned sympathetically and expected that to be the end of the conversation.

He opened his briefcase again and took out the file compiled by the efficient Giorgos. Everything was clear, the bill was acceptable, and Maurice, his London agent, would approve. He should ring Mark next and make sure everything was on track at his end.

Before he could do so, he was interrupted by an unexpected question from his new acquaintance.

‘Can you tell me, perhaps, a good place to rent a bike?’

The Greek was smiling as if at a private joke, his fresh glass of beer held chest-high on the way to his mouth. Day paused in the act of reaching for his mobile.

‘Bike rental? Pedal bike?’ he said.

The Greek laughed. ‘I’m a cross-country cyclist. I’ve given my old bike to my nephew. I’ll buy myself a new one, but I’ll rent for a while first. It will be a good way to get to know the island.’

‘Right,’ murmured Day, thinking of the steep roads in the hilly centre of Naxos which challenged the gearbox of the Fiat. ‘I’m not the best person to ask, I’m afraid. There must be plenty of good places, though you might want one of those new electric-assisted bikes. A bit of extra help sometimes on the hills …’

The Greek laughed again, showing an array of well-kept white teeth. His hair was curly and dark, flecked with white, his beard and moustache meticulously trimmed. Day wondered whether he also trimmed his generous eyebrows. Too much attention to his appearance, perhaps? Not something Day associated with a cross-country cyclist. His interest was further piqued.

‘Thanks. Have you explored the island much yourself? Off-road?’

‘Quite a bit,’ answered Day, ‘but I go on foot. This is a great island for exploring: lots of ancient pathways, well-marked too. I went to the top of Mount Zas once, when I was a student. I’d recommend it, if you enjoy a strenuous walk.’

‘Perhaps you can suggest a few routes for me, over a drink another time? Until then, I’ve bought myself a good map to get me started.’

‘I expect you’ll find me here at Diogenes.’ Day smiled. ‘When you want to try somewhere really remote, go and look for the Geometric cemetery at Tsikalario. It would give you a long bike ride and an interesting walk. You may even manage to find it, though that’s not guaranteed.’

The Greek looked confused, which was not unreasonable.

‘The Geometric cemetery is an ancient site that’s particularly hard to find,’ he explained, ’but it’s a wonderful place when you get there. It’s in the middle of nowhere with a standing stone – a menhir, in fact – and circles of rocks that surround the old burial mounds. It’s not at all depressing, not like modern cemeteries. It’s the most beautiful of wild landscapes, and historically unique. If you like that kind of thing.’

‘I do. Thank you. I’ll bear it in mind.’

‘It will be on your map, near Halki. Look for Apano Kastro, but don’t walk as far as the old castle or you’ll miss the cemetery.’

‘Thank you,’ said the Greek. ‘You sound like something of an expert.’

Day shrugged and lifted his glass. ‘It’s my kind of thing.’

***

They had no more conversation after that. The Greek finished his second beer slowly, paid his bill and left. Day picked up his phone and dialled the number for Mark Hijazi.

Mark was a freelance journalist and a visiting lecturer at University College London. More importantly, he was well-qualified, having written a book on Mediterranean trade in the Early Bronze Age, and another called Greek Influences in the Black Sea. Day had first met him a few months before in Maurice’s London office, and was looking forward to working with him during the summer.

The phone was answered promptly in Mark’s rather light, well-educated voice.

‘Martin? How are you?’

‘Fine, thanks. You? I thought I’d give you a ring about arrangements for Santorini.’

‘I’m all set. The flights are booked and I’m working on the script. Don’t worry, it’ll be ready in time for you to see it before you go in front of the cameras.’

‘I should hope so,’ laughed Day. ‘Do you want a hand with it?’

‘No thanks, it’s going well. Anyway, you’ve got more scripts than me to get through. All good on Naxos? How’s your wife?’

‘She’s well. You’ll meet her on Santorini. While I remember, you need to confirm your booking at the Villa Fengari. My travel agent has put your name down, but could you drop him a line with your passport details? I’ll send you the address.’

‘Will do. Anything else?’

‘Yes. How’s it going to run at the site? Who am I interviewing?’

‘A chap called Filippos Spyropoulos; he’s a friend of mine. He prefers to be called Filip. He’s not part of the excavation team there, but he’s very knowledgeable and a good personality for film. He’s with the University of Athens – his doctorate was on Akrotiri itself. Don’t worry, I’ll get everything lined up for you.’

‘It would be good if Filip and I could meet the day before the interview. Is that possible?’

‘I think so. Leave it with me. By the way, did you read in the Greek press today about the suspected thefts from the Archaeological Museum at Santorini? No? Go online. It’s breaking news. I thought that place was impregnable.’

‘Nowhere seems immune these days,’ said Day wearily. ‘Look what’s happening at the BM. Before I go, are you in touch with Scott Macfarlane, the series director? You should try to have a chat with him before you meet, if you can. He’s in London, I’ll send you his details. Great guy, seems chaotic but isn’t.’

‘I’ll call him – it will be a nice break from writing the script. Right then, see you on Santorini in a few weeks.’

Day was left feeling positive after the call. He had complete confidence that Mark’s script would be well-written, informative, and brimming with well-known and less well-known facts about Akrotiri, the ancient site on Santorini that was sometimes dubbed the Lost City of Atlantis, a town with streets and houses which had lain buried for centuries beneath a deep layer of ash and pumice.

Much more challenging was the script that he himself still had to write. It might be hard to make this one as exciting to the viewing public as Atlantis, but to Day it was more intriguing. It was the story of the discovery on Crete a hundred years ago of the mysterious Phaistos Disc, and the excavations now taking place close to where it had been found. The inscriptions on the Disc were a modern-day mystery, and the particular obsession of his friend Fabrizio from the Italian School of Archaeology, who was part of the current excavation.

He drank the last of his gin and tonic in a single swallow and brought out his wallet. It was time to head home to Helen and persuade her of the benefits of a short siesta.

3

Naxos

Dr Aliki Xylouri, one of Greece’s most highly respected authorities on Mycenaean history, saw Day walking towards her new dig site across the stony wilderness of inland Naxos.

She stood up and waved to him, and he returned the greeting. An Athenian lady ‘of a certain age’, as they used to say in England when he was a boy, she was still as he remembered her: as dignified and statuesque as a caryatid on the Athenian acropolis.

He had met Aliki before on only one occasion. Their mutual friend Aristos, the curator of the local museum, had invited her to the island to look at a hole in the ground which Day had found in the countryside of Naxos.

It was more than a hole in the ground to Day. It was personal. He had worked out where to look for it, taken a small party to find it, and risked his professional good name by asserting that it might lead down to a Mycenaean tholos (beehive-shaped) tomb some distance below the ground. The Ephorate of Antiquities, in the person of Aliki Xylouri, had tentatively agreed with him. Today, after several days of unrelenting work on his film script, he was rewarding himself with a visit to see how the early stages of the excavation were progressing under her formidable direction.

It was a long walk across rough terrain from where he had left the Fiat. He could see that the site was being properly cordoned off: the flimsy police tape that had initially surrounded it had mostly been replaced by metal fencing panels, and a flat-bed truck nearby contained more panels to complete the work.

The enclosed site was larger than he had expected. It was at least the size of a tennis court, though irregular in shape and far from flat, extending from below the opening he had found up onto the lower slopes of a nearby hill. There were small flag posts at intervals with limp yellow flags indicating areas of interest. Between him and the site were several parked vehicles, including a trailer on which was secured a sturdy portable cabin that would probably become the place where records and finds would be kept securely. There was also a caravan; an awning extended from one side of it to provide shade over a camping table and chairs. Here, he guessed, was where the dig staff would take their breaks.

There was no sign of these people as yet, however; he feared he had arrived before there was much to see.

He had broken into a sweat by the time he reached Aliki, and ran his hand hastily through his hair, but could not suppress a broad smile as he approached her. Her stout boots, old dig trousers and broad-brimmed hat were practical clothing for an excavation in the Greek sun, and yet he knew that not far beneath her forthright exterior was an elegant lady in her mid-sixties who mixed with the elite of Athenian society.

‘Martin! I’m so happy to see you again,’ she said, taking his hand in both of hers. ‘Welcome. You must be excited. I know I am.’

‘Yes, very much so. I hope I’ve not brought you here on a wild goose chase.’

‘Well, let’s think positively. I expect you’d like to have a look round, wouldn’t you? It’s all going well.’

She led the way towards the caravan and Day followed. His eyes were drawn to the place within the compound where he knew the opening to the tomb to be, hidden behind vegetation and debris.

He made sure that his companion did not notice his distraction.

‘I’ll introduce you to Felix, my site manager,’ said Aliki as she strode on ahead. ‘He trained in Germany and we’ve worked together several times. I think you’ll get on well. The rest of the team are due to arrive the day after tomorrow. By that time the site will be fully enclosed, with everything we need in place. Buildings, and so on. As you can see, the security fencing is nearly complete. We’ll have a night guard living in the caravan from tomorrow. We’re already attracting attention, but the local people have been very supportive.’

As they neared the caravan, a young man stepped out into the shade beneath the awning. Aliki beckoned to him.

‘Felix, this is Martin Day. Martin, my colleague Felix Roth.’

‘Hi Martin. It was you who found the opening, wasn’t it? I’m pleased to meet you.’

‘Let’s sit down,’ said Aliki. ‘Water?’

Felix brought out three glasses and a bottle of cold mineral water, and sank into his chair with the suppleness of youth. He looked barely thirty, surprisingly young for his position, and had a ragged mop of dark hair that fell over his eyes. His fingernails were either bitten or broken, and one of his little fingers was bent into his palm. They sat round the camp table assuaging their thirst.