Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

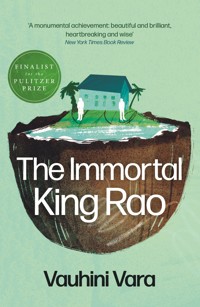

'A brilliant and beautifully written book about capitalism and the patriarchy, about Dalit India and digital America, about power and family and love' Alex Preston, Observer, 'Fiction to look out for in 2022' Vauhini Vara's lyrical and thought-provoking debut novel begins in India in the 1950s, following a young man born into a Dalit family of coconut farmers in a remote village in Andhra Pradesh. King Rao, as he comes to be known, later moves to the US, where he studies in Seattle, meeting the love of his life and his business partner, the smart and self-assured Margie. King Rao ultimately rises up through Silicon Valley to become the most famous tech CEO in the world and the leader of a powerful, corporate-owned global government. Yet he ultimately ends up living on a remote island off the coast of Washington state, an exile from the world which he has helped build. There, in a beautiful home on an otherwise deserted island, he brings up his brilliant daughter, Athena. Shielded from the world's glances, in many ways she has an idyllic childhood, but she will be forced to reexamine her father's past and take steps to try to decide her own future. She is unlike other girls, and she will find the outside world much more hostile than her father did when he left the coconut grove he called home. A profound and moving novel about technology, consciousness and revolution, The Immortal King Rao asks how we build the worlds in which we live, and whether we ever have the power to leave them?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 618

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Vauhini Vara has worked as a Wall Street Journal technology reporter and as the business editor for The New Yorker. Her fiction has been honoured by the O. Henry Prize and the Rona Jaffe Foundation. From a Dalit background, she lives in Fort Collins, Colorado.

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2022 by Vauhini Vara

The moral right of Vauhini Vara to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 649 1

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 431 2

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 885 3

Printed in Great Britain

For my mom, Vidyavathi Vara,and my dad, Krishna S. Vara

Once the choice has been made to organize economic, commercial, and property relations at the transnational level, it seems obvious that the only way to transcend capitalism and ownership society is to work out some way of transcending the nation-state. But exactly how can this be done?

—THOMAS PIKETTY,

Capital and Ideology, 2019

When the superior man has no choice but to oversee all under heaven, there is no better policy than nonaction.

—UNKNOWN AUTHOR,

The Zhuangzi, circa fourth century to third century BCE

1

King Rao left this world as the most influential person ever to have lived. He entered it possessing not even a name.

In the beginning, his mother-to-be stood at the little general store in the center of her village, eyeing the tins of soap piled neatly on the countertop facing the road. It was 1951. Radha had seen this brand before, on excursions to Rajahmundry with her father and sister, but finding a stack of soap tins at their shop, three high and two wide—

PEARS PEARS

PEARS PEARS

PEARS PEARS

—was something else altogether.

Radha was eighteen, and she hated Kothapalli, this hot, wet nothing of a village, nestled in the elbow crook of one of the many canals delivering the Godavari River east to the Bay of Bengal. Its name meant, simply, “new village,” the equivalent in Telugu of all the Newtowns scattered around the English-speaking world. Several variations on the name could be found in the region. This particular village was distinguished, if that word could even be used, by the arrangement of its small center around a circle where the roads converged. In the middle of the circle stood a peepal tree, under which men congregated in the shade, sitting on overturned wooden crates borrowed from the general store, while stray mutts made languid tours around them, hoping for food scraps. Around the circle were the government school, the offices of the tax collector and the village council president, the vegetable and fruit vendors with their carts, a shop selling farm tools, and the general store before which Radha stood.

International products such as Pears, a British brand, did not often appear in Kothapalli’s store. The shopkeeper, one of the most reviled men in the village, was a mean, eagle-eyed miser when it came to his customers, but sycophantic toward the politicians whose favor he required. He was a fat, sweaty man, with the skin of a dead tamarind tree and big, curling lips, black at their edges and pink inside, which he pressed together in a grotesque way that reminded Radha of a fish. He sat behind the counter, perched on a high stool. When customers weren’t around, he passed his time reading or filing his nails with a scrap of sandpaper, his nostrils narrowed in concentration. Behind him was the storehouse where he kept most of the goods: groceries, toiletries, housewares. Under the counter in front of him were the grain and jaggery, in big jute sacks, and the cooking oil, in an aluminum tin.

On the countertop, he displayed items meant to draw the attention of people passing by. He kept his jars of sweets there, for instance, and now that school had ended, children pushed past Radha and lingered in front of the counter, ogling the treats that sat just out of their reach. “Are you going to buy some?” the shopkeeper wheezed at them. He never stopped wheezing, a condition that, because he was a mean man, inspired revulsion rather than compassion. “If not, get out of here!” But a curly-haired boy produced a scarred little coin and asked what he could get for it, and the shopkeeper sighed and began haggling. The rest of the children crowded around, offering their advice about the best use of the coin. And now Radha swiftly grabbed one of the soap tins, stuck it in her armpit, where no one could see it, and ducked around the corner. Once out of the shopkeeper’s sight, she ran past her house, which doubled as her father’s school for Dalit children, to the Muslim graveyard. The roofed, four-arched stone structure in the center had always been her secret hiding spot.

Most people avoided the graveyard, that deathful place, but Radha feared nothing. She was a wild-haired, big-boned, dark-skinned girl. She intimidated people; she knew this. It was partly because Appayya, her father, was a headmaster, and partly because she had brains and an inborn imperiousness. The village store, with its occasional imports from other lands, was the closest Radha had gotten to a more cosmopolitan life. But soon, she had determined, she would move to Rajahmundry. She had applied to the teacher’s college there. For someone like her to be accepted—a girl, a Dalit—would be unusual. But her father had connections, and she was sure that when she told him of her plans, he would help execute them. She would leave him behind, and her sister. They both doted on her, but her father and sister had never understood each other. She imagined them living, after she left, in embarrassed silence, neither able to begin a conversation that wasn’t about her. Still, it gave her only a slight pang of guilt. She’d always had the feeling greatness was in store for her. She was, after all, King Rao’s mother-to-be.

So the air of death that lingered in the graveyard did not faze Radha. She and her younger sister, Sita, had grown up playing there. Now, crouching in a corner of the structure and making as little noise as she could, Radha unboxed the soap and carefully peeled off its paper wrapping, so she could get a better look and feel. She’d never committed such an act as this, but what had she done, exactly? She didn’t consider it stealing, because she planned to return the item. The soap was cool and light in her palm. It had rounded sides and the loveliest color, clear but with a deep amber tint, like an amulet that belonged at the breast of an ancient queen. She turned the soap around in her hand, enthralled. It was the advertisements on the radio and billboards, promising that Pears could turn bad skin good, that had made her so desirous. When she lived in a hostel in Rajahmundry, she decided, she would bathe with one of these.

What Radha wouldn’t have realized—but I can’t help but remark upon—is that Pears had been selling its soaps across the British Empire for a long time. In 1899, at the height of British colonialism, one advertisement had read, “The first step towards lightening The White Man’s Burden is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness. Pears’ soap is a potent factor in brightening the dark corners of the earth as civilization advances.” By the time the Lever Brothers, William and James, acquired Pears toward the end of World War I, it had established impressive markets around the world, including in India. Several years later, when Indian soap sales fell, William Lever suspected that Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement was to blame, so he purchased a little soap-making plant in Calcutta to help him position his products as just as indigenous as the local stuff. The move proved prescient. Soon afterward, in one of the world’s first transnational mergers, Lever Brothers combined with the Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie. When India gained independence and codified its economic nationalism, the Calcutta plant meant Unilever’s Indian subsidiaries could operate under the same terms as any Bombayite competitor. At first, the nationalists resisted. But as Radha entered high school, their opposition was fading. Hence the arrival of Pears at Kothapalli’s store.

Radha noticed someone coming into the cemetery. She froze. It was Pedda Rao, a boy in her class at school, and he was coming toward where she hid. Pedda’s father, the richest Dalit landowner in the village, was a friend of her father’s. Pedda had an identical twin brother, Chinna, but their personalities were nothing alike. Chinna was confident, ambitious, and popular, friends with Brahmins and Reddys as well as Dalits; Pedda was bitter, lazy, and friendless. Pedda peered into the structure, then stood looking at Radha as if expecting something. “Hi,” she said, standing. She had meant to shoo him off with her tone, but her voice, when it came out, surprised her: wet, soapy.

He must have heard it, too. He didn’t answer, but he didn’t leave, either, and after a moment he sidled inside and stood facing her. She supposed he had come there for some private business of his own. But she had been there first. He should wait his turn, she thought, and she gave him a look of annoyance meant to convey this. She was holding the soap at her side, feeling its good, cool weight.

“Is that the soap you stole?” Pedda said.

She reddened. “I bought it!”

Pedda laughed bitterly. “That’s not what the shopkeeper said. I was walking by and heard him telling the children to run and find you. If they did, they’d get a reward. They’re wandering all over town. I thought you’d be in your usual spot.”

The atmosphere between them was charged. If they were both boys, someone might have spat. Instead, Pedda moved close and made a completely unexpected move. Taking her by the shoulders, he spun her to face one corner of the structure and stood right behind her, his hot breath wetting her neck. A strange pressure, hard and soft at the same time, pushed into the curve of one of her hips. She, with the soap in her hand and her desire—not for him, but for the soap, for the life she had promised herself—went mute. His hands cupped her hips and pulled her to him, and he bucked against her, while she stood perfectly motionless, holding the bar of soap tight in her fist. At one point she thought he had unzipped his pants. She should scream and flee, that would be the correct thing to do. But there was that desire. She was not herself. She cried out, and he did, too, spurting a warm jet of fluid onto her langa.

From down the road came the shopkeeper’s voice. “Hey, who’s that in there?” At once, he was at the arch, peering in. “What’s this? What’s this?” Pedda gasped, pulled away, and sprinted out of the cemetery, leaving Radha alone to confront the shopkeeper, who stood there breathing so heavily she could see his gut moving up and down. “The children saw what you were doing in here,” he said. “They ran and got me.” He took her roughly by the shoulders, and steered her toward the village center, shouting in the direction of her father’s school as they passed, “Headmaster, hey, see what your little girl is up to! Master, wait till you find out what I caught her doing!”

Radha’s father came out of the school. The shopkeeper called out over his shoulder, “I know she’s not a bad girl, but I saw it myself!” In the center, the president of the village council, too, emerged from his office, shielding his eyes from the sun. Radha’s face went hot with rage. She wanted to shout that the shopkeeper was lying, but then, there was the semen’s wetness soaking through her langa and the soap in her fist. The shopkeeper had not even taken it from her. Drop it, little fool, she told herself. It’ll be his word against yours. But she couldn’t bring herself to do it. The ridiculousness of the situation—the joke of it, even though the joke was on her—made a strong impression. In her final moment of freedom, my grandmother-to-be held that bar of Pears with a faint smile and did not let go.

THE MORNING OF the wedding, Pedda told his twin, Chinna, that he didn’t plan to consummate the marriage yet. It was in fact Chinna who had harbored a crush on Radha ever since her father, the schoolmaster, had combined the boys’ class with the girls’. “She’s strong,” Chinna would whisper, late at night. “She’s like a horse.” Ever since the engagement, the brothers had barely spoken. Pedda’s talk of delaying the consummation was his first acknowledgment, albeit an indirect one, of his breach. Chinna flinched. He spat in the dirt. “Don’t be immature,” he said. “You’re going to have to touch her one of these nights.” He added, “It’s not like you’ve never touched her,” and spat again as if expelling something disgusting.

The wedding took place on the Rao property, which everyone called the Garden because the land was famously fertile: The Raos’ livelihood came from a sizable coconut grove around which they had built their homes. It was a good family to marry into. But that afternoon, Radha stood straight-shouldered, as grim and resolute as a political prisoner awaiting her execution. When Pedda, her groom, tied the mangalsutra around her neck and knotted it three times, she did not flinch. She smelled, to Pedda, of sandalwood and sweat. He found her fearsome.

Later on, the feast consumed, the chicken bones and other postprandial debris tossed in a heap for the goats, Pedda and Chinna’s room swept clear, their cot strewn with marigold petals, Pedda stood in the middle of the room looking at his wife, who sat on the cot. It occurred to him that he did not know her at all. They were strangers. Radha sat with her legs folded to one side and her back pressed to the wall, tracing the henna designs on her feet with her finger. Pedda murmured, almost as if to himself, “I’m not like other men.”

“Men!” Radha said, her lips twitching a little. She spoke precisely, every vowel and consonant standing erect in its place, the verbal equivalent of good posture.

“Other men like to show off about how great they are,” he said. “I take action.” He had rehearsed these lines, but his words now mortified him—stupid, grandiose. He wondered if Chinna, who was sleeping out on the veranda tonight, since their room had been turned into the marital chamber, could hear the conversation. The horror of it.

Though Pedda was technically the older one, having been born nine minutes before Chinna, he knew he was less impressive by all other metrics. Chinna was handsome and sharp-featured, Pedda soft and lymphatic. Chinna attracted friends and admirers everywhere, while Pedda repelled them simply by entering a room. It must have been Pedda’s perverse sense of competition with Chinna—it never left him—that had compelled him toward Radha that afternoon in the graveyard. He had never regretted anything more.

Radha picked up a marigold petal and tore it in half. “Great,” she said.

“I mean we’ll work together, side by side”—but he was losing his thread—“because you’re strong, you’re like a horse!”

She laughed harshly. She might as well have slapped him. “A horse!” she said. “But, no, dear husband. I’m going to be a teacher, not a farmer.”

Oh God, what had he done to get to this point? But she’d had a part in it, too, hadn’t she? She had pressed against him, he could have sworn she had. And hadn’t she been the one to steal that soap, to refuse, even, to return it to the shopkeeper once she had been discovered, like some kind of imbecile? Now here she sat frowning on the cot as if she were the victim. His ill will toward her thickened. His arms were spring-loaded; it took effort to keep them at his sides. After a while, she stood and walked just past him to the far corner of the room, where her belongings lay folded in a chest. With her back to him, she reached between her breasts and unfastened the hooks of her blouse under her sari.

A small swell rose in him, some combination of care and lust. He focused on this, encouraging it to expand and displace his anger. “That must feel better,” he said.

“Don’t look at me,” she replied.

He fixed his gaze toward the bed and silently counted the marigold petals there, one, two, three, four, and heard the rustle of his wife undressing, five, six, seven, and was reminded of his childhood, when his cousin sisters used to strip in the rain and splash naked in the shallow pools of water that collected at the edge of the clearing between the house and the coconut grove. The boys sometimes stole the girls’ underwear and threatened to feed it to the stray dogs. “Idiots!” the girls shouted, coming at them with clawed hands. “Get back here, we’ll break your rotten teeth!” The girls were leaving now, one by one, married off.

His wife moved toward him. She had changed into a plain cotton sari, ocher-colored. She walked past him to the cot, where she sat and undid her braid, releasing her hair into loose waves around her shoulders. Without looking at him, she pulled her legs onto the cot, turned away, and lay curled against the wall. He bristled with desire, but what was he supposed to do? The minutes stretched on forever. From her careful breathing, he could tell she wasn’t sleeping. Finally, he sat on the bed and put a hand on her shoulder. When she didn’t recoil, he said, “You look like a mendicant, Lemon.” It was her father’s nickname for her, which he’d overheard. She froze but didn’t open her eyes. “They wear those red robes,” he said, overexplaining.

“What did you call me?” she said.

He laughed nervously. “I’m going to call you that from now on,” he said.

“Don’t,” she said, and shivered.

“Cold?” he said, rubbing her shoulder, and when she didn’t answer, he said, “Lemon, are you cold?”

“No,” she said. She gave a shrug so violent that his hand slipped from her.

He moved closer, raising himself on an elbow so that he was propped above her. Her scent was musky and vegetal—mannish. “I can keep you warm,” he said, his voice sounding roguish even to himself.

“If you touch me,” she said, “I’ll scream.”

“But I’m your husband.” He couldn’t understand what his brother saw in this girl.

“I swear this time I’ll scream.”

The truth was that she terrified him. But he gathered his courage and rolled close to his wife, taking her in his arms. Her breath caught. “I told you, don’t touch me,” she murmured. He didn’t move. “I mean it,” she said.

But she wasn’t as insistent as she had been earlier, or at least she didn’t seem so to him. From behind, he clamped his hand over her mouth, hard. He straddled her, shifting her onto her back and holding her legs down with his own. He had expected her to scream, as she had promised, but now she only stared up at him with wide, wet eyes, as if waiting to see what would happen next. He pulled her sari and petticoat up past her knees and moved into her, and she gulped a couple of times but lay quietly, still staring up at him. He kept his hand over her mouth and pumped on top of her. Radha’s breath was hot and wet on his palm. “I love you! I love you! I love you!” he said.

She thrashed her head around. Her hair caught in her mouth, and snot dripped from her nose; she was crying. There was so much fabric between them. All those ocher folds. He pressed himself to her tightly and said, “My wife!” There came a swell of joy and a bursting and, finally, emptiness and shame. When he extracted himself, he found blood on his thighs.

“I’m bleeding!” he said with alarm.

“No, dear husband,” she said. “I’m bleeding.”

In the middle of the night, he awoke to find Radha in the corner of the room near the chest, with her back to him, fully clothed. She was untangling her hair with her fingers. Now she stood looking at the henna designs lightening on her palms. It was a bad omen, the early oranging.

“Are you all right?” he said.

She turned to him. “The color’s fading,” she said.

“Come back to bed, Lemon,” he told her, and to his great awe and gratitude, she did.

WHEN RADHA RETURNED, six months later, to her childhood home behind the schoolhouse rooms, she insisted to Sita that she had allowed it to happen only once. Sex, she told her sister, was an inherent violation. She had closed herself off to her husband after that one awful night, which was to say she knew for a fact that it had been that night’s violence that had produced her unborn spawn.

Sita was Radha’s opposite, the kind of girl who saw no gain in asking for more than she was given. When Radha disappeared into the Rao fold after the wedding, neither visiting nor spending more than a couple of minutes with Sita and her father when they came to the Raos’ place themselves, Sita had accepted it as the new order of things. She was sitting on the veranda of the school when their father brought Radha home, to spend the rest of her pregnancy there, according to custom, until the time came to give birth. Sita leaped up and led her sister into their father’s bedroom, and when her sister had lain down, Sita brought her a glass of lemonade.

Radha, Sita noticed, did not look well. Several months had passed since they had been alone together, and Radha’s bulbed stomach made her seem even more like a stranger. Though her stomach was rounded, the fat seemed to have dissolved from her arms and hips, and a fine line had appeared beneath each of her eyes. Sita had expected her sister to seem radiant, like young brides in stories she had read, but the opposite was true. There was a darkness to her sister that she’d never seen. It frightened her. She hoped the real Radha had hidden somewhere inside this other woman and wasn’t lost for good. “Those hicks in your new family are overworking you!” she gently teased. She added nervously, worried that her sister’s alliances might have shifted since her marriage, “I’m just teasing.”

Sita was sitting on the foot of her sister’s bed, her knees up, drilling Radha about her life at the Raos’ home. Appayya had prepared his room for Radha so she could rest well and wouldn’t have to share a bed with her sister. He moved to the schoolroom floor, where he slept on a rolled-out pallet. Still, Radha shunned her father. She was irate with him for forcing her into marrying Pedda. He let people think of him as a progressive man, but he had shown himself to be as spineless as any other.

Even putting aside the horror of the wedding night, Radha admitted, she hadn’t wanted a child at all. Once she gave birth, she would have to stop her studies and stay at home. Even though she hadn’t had many chores at the Garden because of her pregnancy, she had failed at the ones she did have. She had tried at first—valiantly, even, waking at three in the morning to start the breakfast preparations and wash laundry by moonlight before going to school—but she wasn’t used to it. At home, their servants had always done the housework. At the Garden, everyone was expected to pitch in to keep the operation running; for the women, that meant taking care of all the cooking and cleaning. The women of the Garden, it was said, often died before their husbands did.

The smoke from the kitchen fire made Radha’s eyes redden and hurt, and she tired so quickly at the big mortar and pestle that her chutneys turned out fibrous and bitter. Once, she caught pneumonia from the nighttime chill and had to spend days in bed. She heard the wives of Pedda’s cousins mutter that they’d thought she was strong. Her whole reputation had been for being strong.

But she had not entirely shed the fortitude for which she was famous. When she was alone, she’d privately terrorize the unborn creature. Get out of here, she told it in her mind. Leave me alone. Sometimes she punched her stomach to punctuate the point. When she imagined the creature, she thought of a leech that couldn’t be dislodged from inside her. It made her ill. In the mornings, she woke early so the others wouldn’t overhear her vomiting in the outhouse. She still had hope that the creature would receive her messages: Get out of here. Leave me alone. The creature ate her food, shared her blood. Wasn’t it possible that it could absorb her thoughts?

“Well, what if she can hear and still gets born?” Sita whispered. “She’ll grow up thinking, My mother hates me; I heard her from in there before I was born. It’ll mess up her whole life! Don’t think such thoughts!”

But the creature wasn’t innocent, Radha hissed, it was a monster. When she punched it, the monster punched her in return. This was war, it was violent, it wasn’t the magical experience people talk about. “Plus, it isn’t a daughter,” she added. “It’s definitely a son.”

WHEN RADHA’S CONTRACTIONS STARTED, the midwife came over and climbed onto the cot. Sita watched the midwife part her sister’s legs and peer between them. But the midwife gave a short, sour laugh, and said, “Stop being a pervert and go sit next to her.” Chastened, Sita moved to place herself on the floor next to Radha’s head.

The midwife chattered as she pressed at Radha’s stomach. She made a mean comment about a mutual cousin of theirs who was an albino, and Sita laughed heartily, not out of appreciation but because she wanted to be on the midwife’s good side. She held Radha’s work-toughened hand and pressed on the veins of her sister’s wrist. Soon, she thought gloomily, she would be married herself, find her own belly expanding into a hard, venous balloon with a knotted center, and end up on this same cot with the midwife’s fist between her legs. It made no sense. She still felt like she and her sister were children.

She squeezed Radha’s hand, but her sister’s eyes were shut in pain, and she didn’t return the squeeze. The curves of Radha’s nostrils flared, and dots of sweat bloomed on her brow and dripped into her hair. She made wet grunting noises. Many hours passed. The contractions narrowed, and Radha began screaming. Then the midwife committed an act of sheer violence. Kneeling, she shoved her hand into the flesh between Radha’s legs. Radha mewled and moved like an animal being butchered. Sita gripped her sister’s shoulder, but Radha flung out an arm and cried, “Get off!”

How could birth so resemble death? The midwife’s bony wrist flexed inside Radha. Then out it came, covered in blood and a whitish grease, the infant’s head grasped in the midwife’s hand like a cut of meat. The whole child emerged unbreathing. The midwife held him upside down by his legs in one fist and, with her free hand, whacked his backside until he wailed.

My father was born with his eyes wide open and crust-rimmed. He had a muddy, eczematous complexion. From his belly, a glutinous rope swayed until the midwife pinched it between two fingers and snipped with the scissors her husband used for barbering. She laid the umbilical cord and the scissors at the end of the cot near Radha’s feet. Only then did Sita turn from the spectacle of childbirth and notice her sister. Radha’s breathing was labored, and her face was pale. She didn’t smile, nor, when the midwife held the child out, did she raise her arms to receive him. She fluttered her eyelids and groaned. Some spit bubbled from her mouth, reddish, like rusted water. Had she bitten her tongue?

Sita wiped the bloody saliva with her thumb and touched her sister’s forehead. It was wet and hot. “Is she supposed to be like this?” she asked, and the midwife hadn’t yet answered when blood began trickling, then gushing, from between Radha’s legs. Sita sprinted down the street to where the doctor, a Dutch man known as the Hollander, lived. But by the time they got back to the house, Radha’s lips were purpling. The umbilical cord had fallen to the floor in a pool of blood. Their father was crouched over Radha, clutching her hands and shouting her name. Sita was peering at him, uncomprehending, when the midwife thrust the swaddled child at her. Sita turned to her father. Should she reach out to him? Hand him the child? Radha would tell her, she thought for a confusing moment. Radha would know what to do.

IF RADHA HAD a given name planned, she had kept it secret from everyone, including Pedda. Even the child’s surname was up in the air, since it was not clear whether, in the final accounting, he would be taken in by Pedda’s family, the Raos, or by his late mother’s.

Appayya blamed Radha’s in-laws for her death—his friendship with Pedda’s father be damned—and wanted to demand a refund of the dowry. But Sita was in the throes of an uncommon fit of willfulness. If she married Pedda and adopted the child, the Raos couldn’t demand a new dowry; it would be distasteful. “Your grandson is part of that family, even if you don’t like it, and this way you don’t have to pay another dowry for me to marry someone else,” Sita said. Appayya, normally a man of unbending judgment, had shrunk in his grief. In the end, he didn’t agree with his younger daughter’s plan so much as he stopped protesting it.

They had been calling the boy only “him” or “the child.” Sita wanted to name him as a rebuke to those who pitied him for having been born under a bad star. Raj, she thought, or Raja. It was Pedda’s brother Chinna, an Anglophile, who convinced her to use the English version of the name. King. She figured she had better listen to him. She and the baby were to be Raos, and as a wife and a son, their selves would be subsumed into the Rao collective. Pedda and Chinna’s father was getting old, and while Pedda should have been next in line to assume the family throne, technically being older, no one expected much from him. Chinna clearly would be in charge.

A big name for a little runt, some of her new in-laws teased. But Sita wasn’t in the mood. “He has strong bones,” she responded, straight-faced. “He has a regal lip.” Sita had hired a neighbor girl to nurse him, and the child drank from her breast with slurpy gumption. “He has a strong suckle,” Sita said. “He’ll live up to it.”

Radha was dead. Long live King Rao.

2

But this cold morning, dear Shareholder, King Rao is three days gone. It shouldn’t surprise me that all these people whose names he never mentioned to me—religious leaders, mega-influencers, vice presidents of this and that—parade forth to eulogize him on Social. Still, it galls. It galls. The correctional officers on my cellblock must be watching the clips: I can hear snippets of the thirty-second testimonials, just faintly, by pressing my ear to the wall of the cell in which I’m being held. The father of the modern . . . the greatest innovator the world’s ever . . . The whole performance, in its pretense, is like a second violence being committed upon my murdered father. I hate them for it. I should be the one publicly celebrating the life of King Rao. Who in the world has a greater right?

It is I, after all, who used to awaken in my crib early in the morning, the sun warming me through my swaddling blanket, screaming a complex and operatic scream—I was never one of those dumb, satisfied infants who blinks herself awake and lies there cooing in idleness—and know King Rao would answer. It is I who, seconds later, would hear the sound of his voice calling out to me, gently, and his sandals slapping the floor as he came toward my room. Entering, he would lean over the crib, untuck the corner of my swaddle, roll me out of it, and kiss me on the forehead, murmuring, “I’m here; Daddy’s here.”

I had an old man for a father. In my mind’s eye, he wears a threadbare, decades-old lungi in blue-and-white plaid tied around his waist. His dark chest is bare, covered with wiry white hairs. His breath is sour, his eyes half-closed, his gray-white hair all mussed up around his head. Pulling myself up to stand, I would run a finger across the pine slats of my crib, one by one, while my father watched, smiling, his eyes bright. The slats were smooth and cool to the touch. On bright mornings, light surged through the east-facing window and bathed the room. I wanted to touch it. I reached out and tried to catch it in my fists.

He sufficed for everything then. He would retrieve me from my crib and sit me on his lap in the big forest-green armchair by the window, feeding me formula from a bottle. I remember his warmth and his strong rancid morning smell. When I finished the bottle, he would put it down beside him on the floor and press his huge old lined palms to my little ones. His hands were dry-skinned and cool.

One morning, as I sat playing with twigs on the floor near my crib, my father dozed off in the armchair. I wanted him to wake up. I used the slats of the crib to pull myself to my feet. He opened his eyes. He put his palms on his knees and sat extremely still, as if I were a deer and he was afraid I would flee. He couldn’t have been more than three feet from me. For the first time in my life, I stepped toward him. The wood floor was cool under my feet. To go barefoot across the room, the floor beneath me—miraculous!

I crossed the three feet and fell forward onto his bony knees, across which his lungi draped, then stood hugging them. For a long time, we remained like that. He was physically slight, five-foot-four, shrunken and slender, though not frail. But he still had a big, strong, expressive face—flaring nostrils, thick lips—and a full head of hair. His hair flopped over his forehead; he swiped it aside. He reached down, pulled me onto his lap, and tickled me until I wailed with laughter. “You did it!” he said. “You walked!”

With that milestone complete, he grew anxious for me to learn to speak. He put me inside the yellow plastic laundry basket and pushed me around the room in it. “Let’s pretend it’s a boat,” he told me. “Pretend it’s a car.” Or, “Look, it’s a train, choo-choo, choo-choo.” He would repeat certain words over and over. “Door,” he said, for example, pointing at the wooden door of my room. The logic of language—attaching words to their particular meaning, putting them in order—came easily to me. I understood what he wanted from me: to repeat after him. But I refused to obey, feigning ignorance. Then, one morning, he said, “Door,” and it happened that I had gotten bored with infancy, it was time to move on, and I said it. “Door,” I said, and because I liked the sound of it issuing from my own mouth, I said it again. “Door!”

My understanding of the word differed from the actual meaning. When he pointed to the door, I was captivated not with the large wooden rectangle with its small brass knob, but with what it conveyed, a passage to the universe beyond the room. I loved spending time outside my room, in the living room, the kitchen, and my father’s bedroom, and I loved being outside the house, too, in the garden and fruit orchards my father lovingly cultivated.

Never, though, did he allow me into the forest beyond. We lived alone on Blake Island, separated from the rest of the world by Puget Sound, and my father impressed upon me, from a very young age, that the wider universe was an unwelcoming place, full of peril. On Bainbridge Island, to the north, lived people who were supposed to be dangerous. Yet I couldn’t help but be captivated by the mysteries beyond what I could see. So that first word—what I thought it meant—was infused with promise, and for a long time I had no use for any other, even as he tried to move on. “Room,” he tried. “Floor.” “Crib.” “Chair.” “Athena,” he said, pointing at me, and “Dad,” pointing at himself. “Athena,” “Dad,” “Athena,” “Dad.” I only replied, “Door.” Door, door, door, door, door, door, door. I wouldn’t give it up, my first and favorite word, the single one I deigned to use.

He only laughed. He didn’t take my refusal to mean much. And it didn’t, not then. I loved my father completely. I loved the soft cloud of hair that stood up around his head in the morning, and the deep creases in his leather-brown skin. I loved his big, broadnostriled nose and his clouded, glaucomic eyes, sagging deep in their sockets. When I grew older, I would sit on his lap in the armchair as he read to me, teasing him by licking my fingertip and rubbing the liver spots on his soft hands as if trying to wipe them off. The flesh of his arms and legs hung loose, and I would hold it between my thumb and forefinger and make a pair of scissors out of my other hand. I pretended it was a bunch of loose fabric, and I, a tailor trimming it.

That was around the time that my father dismantled my crib and took it outside. I sat in the room alone, bereft. The space felt sad and overlarge until he returned with the pieces of a twin bed, its frame painted in pale seashell colors, and put it together. My father excelled at gifts. From the big, luscious garden outside he would bring me cut flowers in little mason jars, which we arranged all around my room—on the windowsills, on the furniture, even on the floor. For a long time, I didn’t know flowers died after being cut, because he replaced them so often that I never had to see a petal wilt or a stem droop. I demanded that he bring me the particular flowers I most adored—the fierce and big-headed varieties, roses, peonies, ranunculi—and he did.

One morning, though, when I was not quite three years old, I bit into the head of a rose. I was old enough to know better, but I did it still. The petals surprised me with their bitter taste. I didn’t tell him what I had done; he didn’t notice the dark, scallop-edged mark on the flower’s head. But the next time he brought me flowers, I grimaced and told him I didn’t want them.

“You love flowers,” he protested, hurt. He crouched next to me, his hand around the jar. He reached out with the jar in his hand.

“I hate them!” I shouted. “I don’t want them!” Out flung my arm. It whacked the jar right out of his hand and onto the floor. He stepped back, crying out, more in bafflement than anger. Though the jar hadn’t broken, the water had spilled out, the flowers arraying themselves prettily in the puddle. I see it now as an omen, my violent rejection of his gift. The damage both ecstasized and terrified me. “I didn’t mean to,” I whispered. It was true that I didn’t. But I also did. I didn’t, and I did. I was becoming a human being in the world. I was becoming myself, a Rao.

THIS MORNING I awoke for the first time in my cell in the Margaret Rao Detention Center to the sound of a soft plop, then another. A pair of pouches had been pushed through the mail-slot-sized opening in the cell door and lay trembling in the tray on my side of the door. I rescued them, wiped them on my shirt, and brought them back to the mattress where I had been sleeping. The cell was cold, small, and eerily quiet. There was the tan mattress on which I had fallen into sleep the night before, no more than four inches thick, which sat on a concrete shelf built into the wall. Besides this, the room contained an aluminum sink and toilet with excellent acoustics: My pee, the previous night, had sounded almost pretty when it landed, birdsong in a coal mine. From the ceiling, a single white bulb glared down as if in judgment. The cell let in no natural light. I couldn’t gauge the time; my sense of morningness was limbic. I sat and sucked on each of the pouches in turn. The cola was bittersweet, like underripe fruit, and fizzed on the tongue. The meal, carrot-flavored, had a pasty mashed-potato texture. I got no aesthetic pleasure from either. He is gone.

3

Can I conjure him from within this cell? Dare I attempt it? The main house of the Raos’ Garden—where Pedda and Chinna lived, along with their parents, and where King and Sita soon joined them—stood in a clearing between the coconut grove and the rice paddies abutting the road to the village center. The house was surrounded by a veranda punctuated with several square pillars, which held up a generous coir roof. The house’s rooms were like train cars, lined up in a row, in the style more common among upper castes than Dalits. To go from room to room, you could either walk through the house or go out onto the veranda from one room and enter another from the outside.

The other Raos lived in modest traditional huts around the property, but the whole clan spent most of their time working together in the coconut grove or gathering in the clearing for meals and conversation, returning home only to sleep. At the edge of the clearing stood three small buildings for communal use—the kitchen, the bath stall, and the outhouse—and beyond them, the thousand trees of the Garden. Some of the trees were strong and fat, others thin like an old woman’s legs. Some bore guava, others jackfruit, tamarind, custard apple, or mango. But the coconut trees were the most important, the source of the family’s livelihood and pride.

On lazy afternoons, as the young King lay back on the dead leaves in the middle of the Garden, looking up at the treetops, his heart couldn’t help but set to thumping. The itchiness of the leaves on his arms; the hard press of the earth against his spine; the heat of the sun and the chill of the shade, simultaneously on his forehead and chest. Up above, the canopy of outstretched fronds overlapped like interlaced fingers. The light came down through the fronds in thin, trembling rays and illuminated the dust and pollen specks that danced in the faintly sulfurous air. The light pressed warm white shapes onto his arms and legs and the earth around him.

When evening came, the mothers would holler into the Garden, “Dinnertime, children! Dinnertime, rascals!” Rubbing his palms together to rouse himself, he would stand and stumble toward the sound of their voices. Running past the coconut trees, past the smaller trees bearing lesser fruits—the guava, jackfruit, tamarind, custard apple, and mango—and past the irrigation tube well and its reservoir, into which a big clear head of water gushed from a spout as wide as his torso, he would arrive at the clearing. At its edge stood the strange, beguiling cashew tree the children all loved, so aslant that its top leaves brushed the Garden’s floor and made a perpetually cool, shaded space where they could all shelter on hot afternoons, pressing their bodies together to make room for more cousins as they arrived. Here was the firstborn son of the firstborn son of the firstborn son of the old patriarch. He mattered. “Here comes King,” his cousins called. “Move over for King,” they called, and when he came to them, the brightness of their eyes and the heat of their bodies provided the answer to a question he could not form in words.

ONE MORNING, not long after the Godavari Delta was declared part of a new state known as Andhra, a bureaucrat representing the Indian Central Coconut Committee came to Kothapalli. The village council president brought the man to the Garden to meet Pedda and Chinna’s father, the Rao patriarch. Grandfather Rao sat in the clearing with King, three years old, in his lap. The government, the bureaucrat announced to Grandfather Rao, had big plans for Kothapalli. The republic, nearing a decade of independence, must learn to be self-sufficient. Mother India must stop relying so much on imports, as if her soil weren’t fertile enough. Kothapalli, with its rich earth and its placement on the bank of a canal, was ideally situated to help fulfill this goal. The politicians from up north had sent him to the Godavari Delta to persuade citizens to plant their own crops; there he had heard that, in Kothapalli, Rao was the man with whom to discuss coconuts. Grandfather Rao responded to the bureaucrat’s flattery with a blast of bombastic untruth. “I tell my grandson this is all for the homeland,” Grandfather Rao sang at him. “All these coconuts are here to feed Mother India and keep her strong and free, I tell him. Isn’t that right, King?”

The Godavari Delta had once been a benighted, backward place, alternating between flood and drought. It had become a region of significance only when, at the height of the British East India Company’s power, the Port of Coringa had been constructed to aid in the passage of goods and bodies throughout the empire. When the Crown took over from the company, the British general and engineer Arthur Cotton had taken it upon himself to build a dam splitting the river into several canals, distributing water throughout the delta while also providing an efficient transportation route. This had turned the delta into one of the most fertile places on the subcontinent—on earth. A child could pluck breakfast from the trees on his walk to school; the bright green of rice paddy fields were, besides coconut trees, the region’s most common physical feature; sablefish leaped into nets at the Dowleswaram Anicut where they spawned. No one hungered much.

Now, with the British having departed, more change was coming. The bureaucrat wanted Grandfather Rao to be among the first to hear that the government planned to carve a gravel road running through Kothapalli that would better connect Rajahmundry, to the northwest, with Ambajipuram and the other market towns located eastward where the river and its canals led toward the Bay of Bengal. The bureaucrat encouraged Grandfather Rao to think about the opportunities this might present.

After the bureaucrat left, Grandfather Rao told King to collect three stones. He dropped them in the dirt of the clearing to form a line. The children gathered around. “This is the city,” Grandfather Rao said, pointing with a stick to the first stone, representing Rajahmundry. “This is our village,” he said, pointing to the middle one. “This is the town,” he said, indicating the last. For as long as they could remember, the network of gravel roads in the region bypassed Kothapalli altogether; the village had been accessible only by dirt roads that turned soupy with mud in the rainy season. But the new gravel road going right through their village, Grandfather Rao explained, would make Kothapalli a really important place.

Grandfather Rao decided on a plan. He let it be known that he was offering low-interest loans to Dalit families in Kothapalli who wanted to start small coconut groves of their own. He wouldn’t ask them to start repaying the loans until ten years later—a full three years after their trees could be expected to start bearing fruit.

When the road work began, Grandfather Rao took King and his cousins to watch. Near the center of the village, they looked on as laborers poured red gravel and smoothed it with a wheeled machine, creating a new road where one hadn’t even existed. The men’s skin shone with perspiration. “Go on, help the workers out,” said the politicians, who had come to take credit for the project, to the children, and King and his cousins ran to the road and stomped on the hot gravel. The laborers watched, smiling. Some of them took it as an opportunity to catch some rest. They crouched on their haunches, wiping at their faces with brown rags, then stuffing the rags into the waistbands of their pants.

The heat of the gravel bit at King’s feet. But he remembered what Grandfather Rao had said. This was the most important event the village had ever seen. He was to remember it well. The gravel. The workers with the rags. The flint-eyed politicians. The village council president, whom people had started referring to as “Mr. President,” brought the politicians one coconut after another. “One day, you’ll take your own children on a walk down this road, and you’ll tell them you helped build it,” he told the children. “Come on and use those muscles!”

Little King Rao used those muscles. He stomped till his thighs burned. One by one his cousins left him and stood by the side of the road. The sun set. Only he was left with the laborers. “Does your boy need work?” the politicians teased Grandfather Rao. “We could use someone like him.” He stomped and stomped. It grew late. The politicians got into their cars and left. The laborers left. Even his older cousins left. Only he remained, along with his grandfather, who watched as he stomped. His heart throbbed with the effort—a good, meaningful feeling, to be working on a project that mattered, and trying hard.

“Remember this,” Grandfather Rao said, pulling King onto his shoulders on the way home. He was old but strong. The sun trembled on the horizon. “Don’t ever forget it. It’s important that this happened, and we were all part of it. You’re like me, like your uncle Chinna. The Garden’s going to be yours one day.”

FOR GENERATIONS, the Garden had belonged not to their family but to a Brahmin clan. These Brahmins were the original Raos; King’s ancestors were known, then, as the Burras. The Brahmins had passed the land from father to son like some treasured antique, their ownership compounding with each inheritance and growing more absolute. King’s ancestors had taken care of the Garden all that time, but they had lived in a tumbledown settlement of huts far from the center of Kothapalli, so distant that it wasn’t really part of the village at all. This was by design, since they were Dalits and not allowed to mingle with the other castes. People called it a great partnership, that of the Brahmin Raos and Dalit Burras.

But when Grandfather Rao was a child—when he was a little boy named Venkata—the sons of the Brahmin patriarch had moved to Hyderabad, and the patriarch’s wife had died, leaving him alone at the Garden. One day the Brahmin told Venkata’s father that he had acquired a smaller home in the center of Kothapalli and wanted Venkata’s father to take over the Garden, as a tenant and a caretaker, helping him sell the coconuts in exchange for a small share of profits.

Venkata, the oldest of four siblings, was six years old when they arrived, his father shouldering jute sacks filled with their belongings. Venkata’s littlest sister, Kanakamma, his favorite among his siblings, had not even turned one. His mother carried her while the middle siblings, Babu and Balayamma, each held one of Venkata’s hands.

The Brahmin was standing on the veranda of his house, looking as if he had been waiting a long time. He gripped the keys tightly, and for a moment it appeared he would refuse to hand them over after all. They waited in the clearing for the Brahmin to come and meet them there, and when he didn’t, Venkata’s mother nudged his father, and his father climbed the stairs, his head bowed as if for benediction. Even when he stood in front of the Brahmin, he didn’t raise his head. The Brahmin looked at him and said, “What a damn shame.” His knuckles trembled around the keys. Venkata’s father put out a hand to receive them, and finally, without a word, the Brahmin let them drop. He walked down the stairs and turned onto the path bisecting the paddy fields, toward the main road.

“Where’s he going?” Venkata wondered aloud.

“Home,” his father said, but even he looked uncertain.

“I thought Brahmins didn’t swear.”

“Some do, some don’t.”

Over at the Burra settlement, people whispered that the Brahmin had anointed Venkata’s father because he was obedient, not because he was intelligent, confident, or otherwise well equipped to run an enterprise the size of the Garden. He was short and lean, with thin, oily hair, a scoliotic posture, and the ribs of a stray tomcat. The years passed, and he diminished. Before long, his four children were each at least a full head taller than him and could see the dandruff caught along the widening part in his hair. He wore the same threadbare lungi around his waist every day. He never spoke much, and when he did, he muttered the palest platitudes. He told his children that they had the Brahmin to thank for their fortune, though everyone knew the Brahmin had been forced to let their father manage the Garden because of his own ineptitude. When the children questioned their father, he only hissed at them, “Don’t be disrespectful; don’t come to me with that talk.” He looked afraid rather than menacing, his shoulders hunched and his eyes darting. It was as if he believed the Brahmin would abruptly appear from behind the trees, like some demon.

Because Venkata was the oldest, his father began sending him, at the age of eleven, to visit the Brahmin at his house in Kothapalli’s center, to take care of whatever needed doing. His next-oldest siblings stayed behind to help at home, but Kanakamma, being the youngest, at six, and still free of responsibility, liked to accompany him. He never minded. Kanakamma remained his favorite, a small, pliant, doe-eyed little tagalong. He enjoyed taking care of her and having someone to terrorize. During monsoon season, the Brahmin made Venkata arrange big earthen pots on the floor to collect the rain that poured through the leaking roof, and dump them outside when they filled. It was tedious. The Brahmin didn’t take care of repairs, and over time the earthen pots multiplied on his floor.

He always left the house when Venkata and Kanakamma came. It would be taboo for him to be seen sharing an enclosed space with untouchables, breathing the air they breathed. Venkata wanted to show he didn’t care what the Brahmin thought, and so he made a game of it. He constructed an obstacle course with the pots and had Kanakamma count the seconds it took for him to complete it. Kanakamma, a rule-follower of a child, would wring her hands, glancing at the front door, and whisper, “Okay, but be careful.” One afternoon, he slipped and kicked a pot; it toppled and broke into pieces. “I told you,” Kanakamma said, whimpering. “ ‘Be careful,’ I said.” Venkata told her to toughen up and made her hide the broken pieces of the pot in the folds of her langa. They ran to the Burra settlement where they used to live and buried the pieces there with the help of their distant cousin Kothayya, a gentle boy, who was in love with Kanakamma. Kanakamma cried softly the whole time, while Kothayya consoled her. “Don’t be babies,” Venkata scolded them both, but he was fearful, too. “You better not tell anyone,” he said to Kothayya. If they were caught, they would be beaten, not by the Brahmin, but by their father.

For days, they were afraid. Kanakamma cried at the slightest provocation, and Venkata eyed her with menace, silently warning her not to tell. One evening, the Brahmin appeared unannounced at the Garden while they were all eating dinner, with an unfocused expression in his eyes. Venkata and his siblings sat cross-legged on the veranda, little piles of rice, lentils, and okra arranged before them on bright green banana leaves. Kanakamma, who sat next to Venkata, pinched his arm and tried to meet his eyes, but he shook her off and kept eating, as if the visit had nothing to do with them. Their mother ran and brought out the stool for the Brahmin.

“Please, sir, sit, sit, sit,” their father stammered to the Brahmin, gesturing at the stool.

Venkata hated seeing his father abase himself and hated the Brahmin for causing it. The Brahmin lurched up the steps to the veranda and onto the stool and sat there wobbling to and fro. Their father, who stood to the side of the stool, kept thrusting his arms out as if preparing to catch the Brahmin.

“Stop it, I’m fine!” the Brahmin shouted. He added, more quietly, “I know what you’re suggesting. First, my sons call me a drunkard, and now my tenants, too.”

Venkata looked up from his plate. The Brahmin was a drunkard. What a thrilling revelation—a Brahmin, and a drunkard! He wanted to laugh.

“Those damn kids,” the Brahmin said. “I doted on them, and now I’m old, and they’ve deserted me. I swear, I never took a sip of