Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

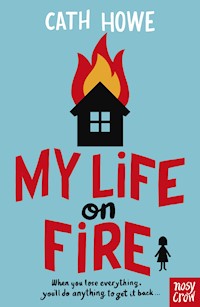

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Secrets. Lies. Promises. Sometimes keeping things inside is dangerous. Callie, Ted, Zara, and Nico are best friends. More than friends - they're like family to each other. But since being embarrassed at school in a practical joke gone wrong, Ted has stopped talking to the rest of the gang. And when Callie, Zara and Nico discover that someone has been living in their school, and sleeping in the building at night, they decide to investigate - without Ted. A wise, heartwarming story of friendship and family, from the highly-acclaimed author of Ella on the Outside, Not My Fault, and How to be Me.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my parents, D and D

Chapter 1

Callie

I used to think I knew my friends so well. But now I think friends are mysterious icebergs. There’s so much going on under the surface.

Friends are like the family you choose. I read that on a birthday card. I don’t need a bigger family, that’s for sure; there’s six of us. I did sort of choose my friend Ted. We’ve been together since nursery. We always sat next to each other and sang and played with the bricks. He’s small and very quiet and he hates speaking in class. He won’t ever answer a question unless the teacher says his name, and we all wait for him to open his mouth. Mostly, he’s just quiet. We don’t need everyone to be noisy, do we? Ted’s like a cat appearing beside you, watching. You wonder what he’s thinking.

Recently he’s got even quieter. I often sit beside him for a chat on the planter at lunchtime, looking out over the football game, but these days it’s mostly me chatting and him listening with that concentrating expression he has.

I wonder if part of the reason he got sadder was because he stopped coming round to my house after school each day. He had been coming to us for years. But this term his mum rang and 3cancelled it.

Also, a few weeks ago, a big thing happened to make Ted feel much worse.

We were planning our class assembly and we were told we had to read out a letter pretending to be a soldier writing to his family from the trenches in World War One.

Ted didn’t want to do it. Every time we practised, Mr Dunlop shouted at him, “Can’t hear you!” and “We’ll have no wimping out in my class.”

Ted flushed and his voice came out smaller and smaller until it was a whisper. I wanted to help him improve but, even though he lives next door, we don’t usually see each other outside of school now. I had loads of netball sessions ready for a big competition too, so I was very busy, but I did try to give Ted some tips during playtimes. We practised being louder and not looking right at the audience but at a place above their heads. But he really didn’t get any better.

“I just wish someone else could read it out,” he kept saying. So the whole class knew how wound up he was.

On the big day, five minutes before our assembly started, a whole group of kids from my class were 4messing about, chasing each other with water bottles because our teacher had gone out of the room. Just as we were about to file into the hall, a boy called Billy Feldon squirted a carton of orange juice down the front of Ted’s trousers. Ted didn’t notice. Not at the time. I certainly didn’t or I would have told him. Especially because of what happened next.

We lined up and walked silently down the stairs into the hall, all the way to the front. The whole school was in there. We all filed along and turned to face the audience. That’s when everyone saw the dark wet patch right across the front of Ted’s trousers. He looked down at that exact same moment and did a kind of terrible gasping face. So of course we all thought Ted had wet himself, because of being so nervous. It was terrible because Miss James called out, “Ted, love, let’s sort you out,” and Ted had to come out of the line and walk back out of the hall in front of the whole entire world!

After that, Ted wouldn’t talk to anyone. His mum went to see the head teacher and THE TRUTH CAME OUT about Billy and the orange juice because some people had seen what Billy 5did. We all discussed whether Billy would get suspended. But I don’t think squirting orange juice was bad enough, especially as Billy just kept saying the squirting had been an accident.

My friend Ted seemed different after that. I heard a couple of kids calling him Toilet Ted one break time. School can be mean.

Chapter 2

Ted

I wasn’t always a night visitor.

High up in the tree in my garden, inside the clustering leaves, I looked down on Callie’s garden next door.

If I concentrated, Callie felt nearer.

Everything in my head crowded into remembering one thing: that day, a long time ago, when we were playing in her garden and a friend of Callie’s mum’s had pointed to me and asked Callie, “Is this one of your brothers?” And she had smiled with her whole face and said, “No, Ted’s my nearly-brother.”

I felt warm through and through.

That’s what I was: a nearly-brother.

But I ruined it. I made a mistake, just after term started two months ago.

Mum and I had just come back from the doctor’s for my height and weight check.

I remember Dr Lowell’s questions.

“Well now, how does he eat?”

With a knife and fork, you weirdo! I thought.

“He’s fine, Dr Lowell,” Mum said. “He’s got a good appetite.”

Why didn’t he ask me?

“Ted’s below average for height but he’s still 8within the range.” The doctor pointed to a chart with coloured columns and percentages. “He’s here, at the lower end. We might do a few blood tests, just to be on the safe side. Ask at the desk and the nurse will sort you out.”

“Well now, sweetheart,” the nurse said when we got there. “What can I do for you?”

She didn’t call Mum “sweetheart”! That’s what gets me: the sort of words people use when they talk to me. “Poppet”. “Honey”. That voice. Patting me. People always think I’m younger inside my head as well as being small.

Sometimes, though, I wonder what would happen if I never got any bigger. Would they keep me at school forever? No one would ever take me seriously. I dreamed once that they took me back into the infants. We think you would be happier in here.

On the way back from the doctor’s, we stopped at the supermarket. When we got home, Mum looked at the receipt for the shopping and sighed. “We’re going to have to cut some corners. Money’s tight.”

Mum is a bookkeeper. She does accounts for local businesses. She’s always working, but 9everything’s getting more expensive. And she had just had to pay a big bill for our heating to be mended.

Just like that, I said, “I don’t need to be childminded at Callie’s every day after school. That would save us some money.”

Mum stopped putting away the shopping. “I thought you loved going to Callie’s?”

Then, instead of saying, “Yeah, I do,” I said, “Plenty of people in my year walk home on their own and let themselves in.”

Mum nodded. “That’s true.”

“I’ve got a key.”

“Course you have.” Mum looked pleased now. “Great. I’ll ring and sort it.”

It was waiting on my tongue to say, “Don’t!” I just had to speak. But I didn’t.

I know why. I suppose I was fed up of people thinking I was a little scrappy kid. I didn’t need to go to Callie’s and stay for tea and play in her garden with the other kids until Mum got back. But I did want to. Just – in that moment, in that split second, I forgot how much.

But now, as I realised that part of my life would be gone, a huge lump arrived in my throat.10

I watched Mum pick up her phone and call Callie’s mum. We were going to make our own arrangements from now on, she said, smiling over at me. “Here’s a week’s notice.”

It was like the door of Callie’s house had firmly closed in my face.

I would be a visitor now. And it was my fault!

Chapter 3

Callie

Half term came and went, and on the first Monday back we had another assembly and in this one they told us they were choosing new prefects. Prefects were like super pupils, I always thought, when I was in the infants. And today our teachers made a massive fuss about how important prefects were, saying it was a special job. If a visitor came to the school a prefect could show them round, or they could get the hall ready for assemblies, or maybe do the sound from the laptop, sitting on a chair at the back. Prefects set an example, they said, and we all sat up straighter, as if someone had pushed a pole down our backs.

When we went out to play afterwards, my friend Zara said, “Would we miss lots of lessons if we’re prefects?” because Zara hates missing anything.

Nico said, “Who cares if we miss stuff?”

I secretly thought I had a good chance of being chosen because I was in the netball team and not usually late for school, even if I did have to run some mornings. I only live round the corner but that makes it worse, I think, because I don’t leave enough time to get to school, like I’m expecting to fly there. My garden backs on to the playground, so I can hear people arriving and 13games of football while I’m frantically trying to find things in the kitchen with the minutes ticking down until I’m officially late. But I always make it, dropping stuff, still pulling my coat on, legging it up the road and tumbling into the crowds by the gates.

Nico is the tallest person in our class. “I can look over things,” he told us. “That might be useful for being a prefect.”

Well, I wasn’t going to get picked for height. And Ted is the smallest in our class so that wasn’t very kind of Nico with Ted standing right beside him. Ted just looked a bit bleak and shrugged.

“My dad always says, ‘They don’t make diamonds as big as bricks’,” I told them. Nico chased me round the back of the planter for that.

Zara said, “Height would be a stupid way to decide. Imagine if the teachers decided who was going to be head teacher by lining up and picking the tallest!”

We all suggested teachers who we thought were tall but then we realised the tallest adult in school was Mr Rafferty, the caretaker. We laughed a lot then.

I didn’t set a bad example at school. Not like 14Billy Feldon who, worse luck, was next to me in the register, so he was always beside me in class. If you had to pick someone to sit next to, you would never pick Billy because: he never sits still, he never has the stuff he’s supposed to bring and he’s just … irritating. He messes around, not in a loud way but like a buzzing fly on a window – you always know he’s there. He borrows my things, he hasn’t brought colouring pencils or he’s lost the worksheet we were given. At parents’ evening, Mum complained that I always got put next to Billy, and our teacher said, “Callie is a sensible girl.” That sounds really boring, but I wouldn’t want to be like Billy, chasing his tail, trying to find something he forgot. He’s always nudging me. “Callie, what did he say?” or “Callie, let’s both use your answer sheet.” He doesn’t even ask nicely!

He’s kind of stupid-silly. He says things like, “What’s an Ig?”

“Don’t know…”

“An Eskimo’s house without a loo.” Then he cracks up laughing.

He’s obsessed with choices: “Hey, Callie, feet for ears or ears for feet?” poking me with a 15ruler. “Callie, Callie, listen. Would you rather be eaten from the inside quickly or from the outside slowly?”

On and on.

His jokes aren’t funny. And anyway, you shouldn’t laugh at your own jokes. We tried to stop laughing at Billy’s after what he did to Ted in assembly.

Billy Feldon has all these theories about our teacher Mr Dunlop. He says Mr Dunlop is secretly a troll. Billy says classic troll behaviour under his breath whenever Mr Dunlop does something we don’t like. Mr Dunlop is one of those teachers who tells us off a lot so that we all feel a bit flat. He’s always disappointed. He’s got this miserable voice and he does long sighs. Billy copies them. A typical day would be:

1. Mr Dunlop telling us off about people fighting over whose turn it is to have the football

2. A general telling-off about behaviour, and then:

3. Threats about losing play times and all kinds of horrible punishments that might happen to us.

Billy will be rolling his eyes, copying Mr Dunlop and sighing, whispering, “Classic troll behaviour” 16in the same low voice. Other classic troll behaviour is a throat-clearing thing that Mr Dunlop does. Billy says that’s because trolls eat disgusting things and they don’t chew properly so there are always bits stuck in their throats.

There’s a window next to Billy and he’s always leaning up against it and rattling the metal arm, making a grating, scraping noise, pressing down and working it loose. Mr Dunlop looks around, trying to work out where the noise is coming from. Billy whispers under his breath, “The trolls are coming.” It makes us happy that Mr Dunlop doesn’t know. It makes us feel that anything might happen.

We don’t want to help Mr Dunlop because he doesn’t want to help us. If we were younger, someone would put their hand up and say, “Please, Mr Dunlop, the noise is coming from that window over there.”

But these days my class just enjoy watching our teacher get cross.

We are unusual in my school, being a four. Zara, Nico, Ted and me. It’s because they chose us four for maths masterclasses more than a year ago. 17Every Wednesday for two hours, the four of us get taken round to Larks Cross, the secondary school next door, for extra maths. There are lots of children from other schools there too, but we always sit in our small group and share our answers to the fiendish reasoning questions. We discovered that Zara was the fastest of all of us. It wasn’t a surprise; she’s super serious and she always gets her homework in on time. Nico was the loudest. And if he thinks he knows the answer he will never change it, even when you have shown him why it’s wrong. Ted hardly speaks, but he has an amazing memory. I like going to Larks Cross because that’s where we’ll go next year and anyway my brother Elliot already goes there so I can look out for him on his way to lessons with his friends. If he’s going past our room, he always does something like jumping high and waving, to make sure I see him.

Chapter 4

Callie

In the afternoon, they read out the names of the new prefects. We all got excited and tried not to show it. I was sure Zara would get picked. I had my fingers crossed under the table. And then … they didn’t pick me or any of my friends.

When Mr Dunlop called out six names, the last one was … Billy!

Billy did this double blink beside me, bolt upright, mouth open. “Me?”

“You?” I said.

I couldn’t believe it and neither could the others. Outside in the crowded playground, Nico was fuming. “I feel as if I’ve been kicked in the head by a horse. Billy Feldon, he’s a disaster on legs!”

“He doesn’t ever get to school on time!” Zara said. “So unfair!”

“That’s not the worst thing,” Ted said, his face like thunder. “He shouldn’t be in our school.”

“Sorry,” we all said. “Sorry, Ted.”

“I think we should go on strike,” Nico said. “Refuse to sit down in assembly.”

Zara nodded. “We should write to our Member of Parliament. Hold a sit-in.”

We found Miss Reynolds on playground duty 20by the drinking fountain. We all like Miss Reynolds cos she runs lots of cross-country events and she celebrates if you try to do something, even if you’re rubbish.

“Sometimes a prefect learns to set a better example,” she said, “by being made one.”

“What about us then?” we demanded.

“There will be more prefect roles later in the year. The best thing you can do is to volunteer for things,” she said. “Like the Maths Challenge, for example. You are an obvious team for that. I’ll put you down.” She grinned. “There’s lots of ways you could be helpful too – how about classroom monitor jobs? If you help, the teachers will remember it next time they’re choosing more prefects.”

Then she got called away to deal with a bang on the head incident.

“Hang on, did Miss Reynolds just volunteer us for the Maths Challenge?” Nico muttered. “Why did we bother to ask her?”

“I don’t mind doing the Maths Challenge,” Zara said. “We could practise. It’ll be fun.”

Nico was still fuming. “I’ll do the maths thing, but I am not sharpening pencils and sucking up 21to teachers! No thanks.”

I wasn’t very interested in sharpening things or trying to find all the missing scissors either.

“If Billy’s a rubbish prefect, could he get deprefected?” I asked.

“Dunno,” everyone said.

I sat on the planter with Ted in afternoon play, watching the football.

“How could they make Billy a prefect? It doesn’t make sense,” I said. “They don’t know what he’s like.”

“Dunlop does,” Ted said softly.

“I don’t think Dunlop really knows what any of us is like.”

Ted looked so fed up.

“Maybe he’ll just be rubbish. I bet he will be,” I said.

Ted swung his legs. “So why choose him? He doesn’t care about people.”

We stopped chatting to watch a builder in a high-vis jacket cross the playground and disappear behind the tarpaulin near the gates. There’s a lot going on in our school at the moment. They are adding a class to each year in the juniors so there will be three classes instead of two. Before the 22holidays started, they all came tramping in past the hall in hard hats with bright yellow jackets. They did an assembly on how to build new bits of a school, showing us the plans for the new classrooms. That was OK, but we’ve got used to them so it’s not so exciting any more.

They were supposed to finish in the summer holidays but they still hadn’t, so we had to listen to them banging and drilling. The inside walls were bare down at that end of school, and there were plastic covers on all the carpets. Outside, the building work was screened off by a tarpaulin like a great big blue sheet around the outside, so there was nothing to see. We were banned from going anywhere near it. When I went for maths masterclasses we could look down and see the new classrooms from Larks Cross. They just looked the same as all the other classrooms except they didn’t have windows yet; four rectangular boxes, two on top of two, and ladders and pulleys and planks and builders up on the scaffolding.

Chapter 5

Callie

Later on that day, we burst out of school as usual. Most of us walk home on our own. The teachers have a list of who’s allowed to.

We set off. Nico and Zara come home with me every day and their parents collect them later because my mum is their childminder.

Ted walked with us then waved when we got to his house. He had his key ready in his hand. “Bye!”

It’s always noisy at home because there’s soooo many of us. There’s my brother Ollie and little sister Chloe, and two other little ones, Timmy and Benjy, who Mum collects from our school nursery at lunchtime. There’s my older brother, Elliot, but he is often out. And with Nico and Zara, that makes eight of us. My sister and brother argue a lot. When everyone shouts, we are a major headache, Mum says.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)